Outpatient clinics are increasingly being recognized for their critical role in facilitating early palliative care access. This systematic review highlighted the lack of consensus in the literature on which patients should be referred in the ambulatory setting. Cancer diagnosis, prognosis, physical symptoms, performance status, psychosocial distress, and end-of-life care planning needs may be taken into consideration when appropriate candidates are being identified.

Keywords: Access, Health systems, Neoplasms, Outpatients, Palliative care, Referral, Standards

Abstract

Background.

Outpatient palliative care clinics facilitate early referral and are associated with improved outcomes in cancer patients. However, appropriate candidates for outpatient palliative care referral and optimal timing remain unclear. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify criteria that are considered when an outpatient palliative cancer care referral is initiated.

Methods.

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1948–2013 citations) and Ovid Embase (1947–2015 citations) for articles related to outpatient palliative cancer care. Two researchers independently reviewed each citation for inclusion and extracted the referral criteria. The interrater agreement was high (κ = 0.96).

Results.

Of the 186 publications in our initial search, 21 were included in the final sample. We identified 20 unique referral criteria. Among these, 6 were recurrent themes, which included physical symptoms (n = 13 [62%]), cancer trajectory (n = 13 [62%]), prognosis (n = 7 [33%]), performance status (n = 7 [33%]), psychosocial distress (n = 6 [29%]), and end-of-life care planning (n = 5 [24%]). We found significant variations among the articles regarding the definition of advanced cancer and the assessment tools for symptom/distress screening. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (n = 7 [33%]) and the distress thermometer (n = 2 [10%]) were used most often. Furthermore, there was a lack of consensus in the cutoffs in symptom assessment tools and timing for outpatient palliative care referral.

Conclusion.

This systematic review identified 20 criteria including 6 recurrent themes for outpatient cancer palliative care referral. It highlights the significant heterogeneity regarding the timing and process for referral and the need for further research to develop standardized referral criteria.

Implications for Practice:

Outpatient palliative care clinics improve patient outcomes; however, it remains unclear who is appropriate for referral and what is the optimal timing. A better understanding of the referral criteria would help (a) referring clinicians to identify appropriate patients for palliative care interventions, (b) administrators to assess their programs with set benchmarks for quality improvement, (c) researchers to standardize inclusion criteria, and (d) policymakers to develop clinical care pathways and allocate appropriate resources. This systematic review identified 20 criteria including 6 recurrent themes for outpatient palliative cancer care referral. It represents the first step toward developing standardized referral criteria.

Introduction

Over the past few years, there has been an increasing call for greater integration of palliative care and oncology, with multiple organizations, such as the Institute of Medicine, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, promoting early palliative care referral for cancer patients [1–3]. Because most oncology patients are seen in the ambulatory setting, outpatient palliative care is particularly appropriate to facilitate early access [4]. Outpatient palliative care clinics are increasingly available, with 59% of National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers and 22% of non-NCI-designated cancer centers reporting their presence [5]. Multiple randomized controlled trials and cohort studies found that introduction of outpatient palliative care from the time of diagnosis is associated with improved quality of life, symptom burden, patient satisfaction, and even prolonged survival compared with routine oncological care [6–9]. Outpatient palliative care referral is also associated with significant improvement in end-of-life care outcomes compared with inpatient palliative care consultation [10].

Currently, the volume and timing of referral to outpatient palliative care for cancer patients vary widely [11]. This is partly attributed to the lack of standardized referral criteria for outpatient palliative care, coupled with variable oncologists’ attitudes and beliefs about palliative care and differences in availability and resources of the palliative care service. A better understanding of the criteria when initiating an outpatient palliative care referral would help (a) referring clinicians to identify potentially eligible patients for palliative care interventions, (b) administrators to assess their programs with clear benchmarks for quality improvement purposes, (c) researchers to standardize the design for future trials involving outpatient palliative care, and (d) policymakers to develop clinical care pathways and to allocate appropriate resources toward development of palliative care programs. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify criteria that are considered when an outpatient cancer palliative care referral is initiated. This represents the first step toward developing a standardized set of referral criteria.

Methods

Literature Search

The institutional review board at MD Anderson Cancer Center provided approval to proceed without the need for full committee review. On December 18, 2013, our clinical librarian searched all the citations on Ovid MEDLINE from 1948 to 2013 and Ovid Embase from 1947 to 2013. We subsequently updated this search of both databases on October 25, 2015, to include the latest publications. Our search strategy consisted of Medical Subject Headings and text word or text phrase for “neoplasms,” “palliative care,” or “supportive care” and “outpatient” or “ambulatory” or “clinic.” We included all original studies, reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, editorials, commentaries, and letters and excluded duplicates, non-English articles, dissertations, and conference abstracts.

After the initial search, two investigators (D.H., S.B.) independently reviewed the title and abstract of each citation for inclusion. Publications were included for further review if either of the two investigators coded that article as related to referral criteria for palliative care. This approach was taken to maximize inclusion. The interrater agreement was high (κ = 0.96; p < .001).

Data Collection

We retrieved the full text of each article of interest and excluded any publications not relevant to outpatient palliative care referral. A few articles provided palliative care referral criteria but did not specifically state whether they were for outpatient or inpatient. We included these articles as well.

Subsequently, we examined each article in detail and extracted the referral criteria. One investigator reviewed all articles for consistency (D.H.). Any disagreements were discussed to arrive at a consensus. If a referral criterion was described by at least five articles (e.g., performance status), it was considered as a major category. This qualitative systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline for reporting where applicable [12].

Statistical Analysis

We used frequencies and percentages to summarize the data. The κ statistic was used to assess interrater reliability. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 16.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, http://www.ibm.com) was used. A p value of <.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

Results

Literature Search

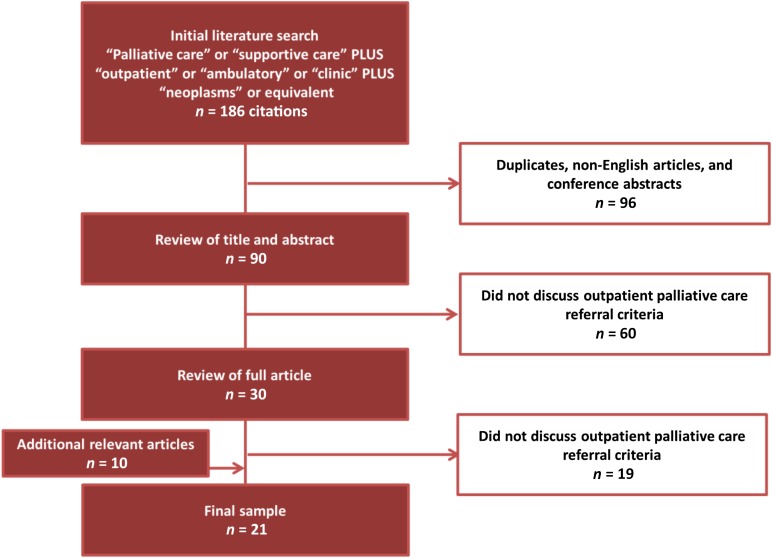

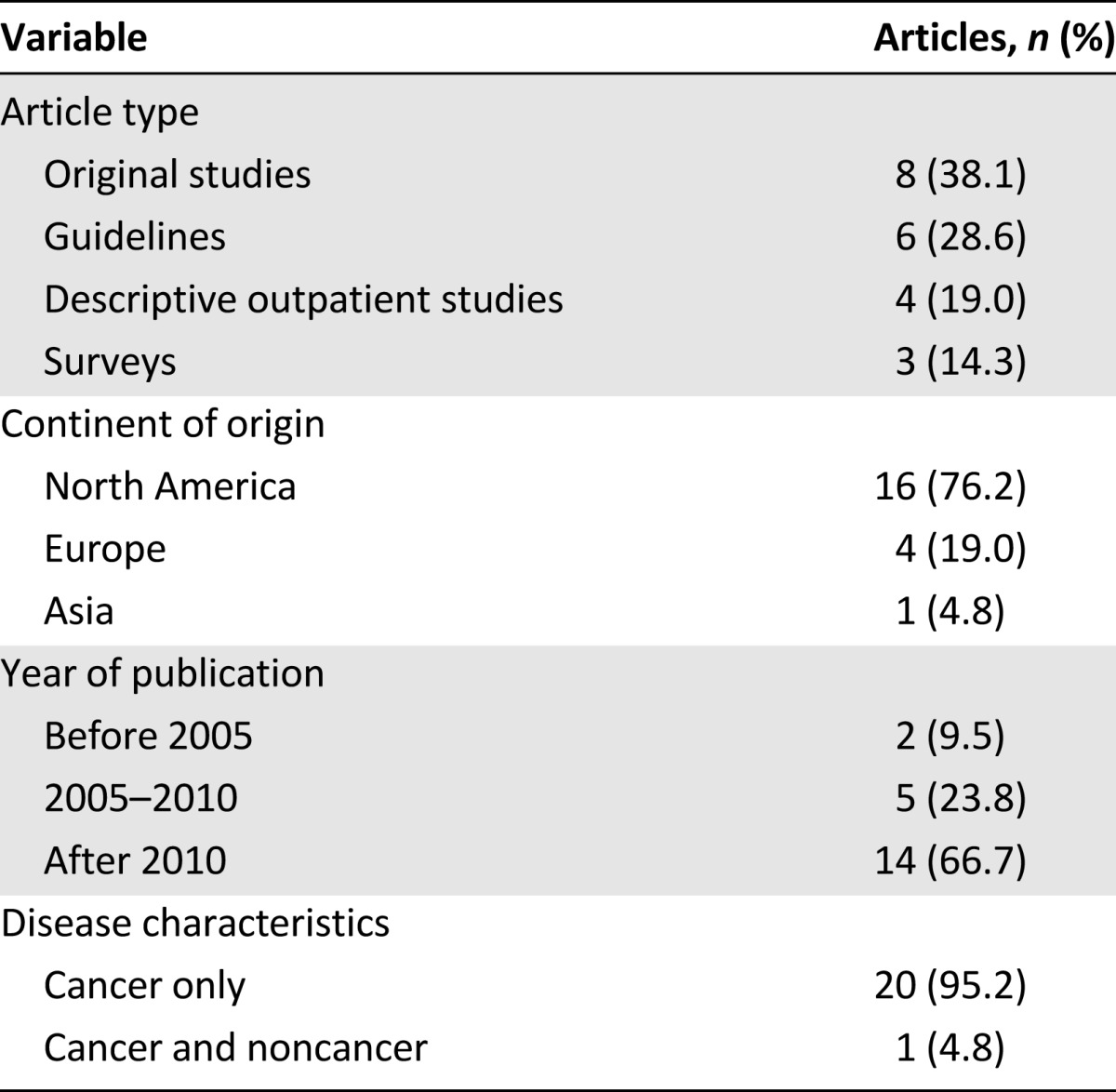

Our literature search identified 186 articles. Ninety-six were excluded because they represented duplicates, conference abstracts, or non-English articles. A total of 90 articles were reviewed, and 21 (23%) were included in the final sample (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the articles are summarized in Table 1. A majority of the studies were from North America (n = 16 [76%]) and were published after 2010 (n = 14 [67%]). All except one of the publications were specific to oncology (n = 20 [95%]).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1.

Publication characteristics

Criteria for Referral

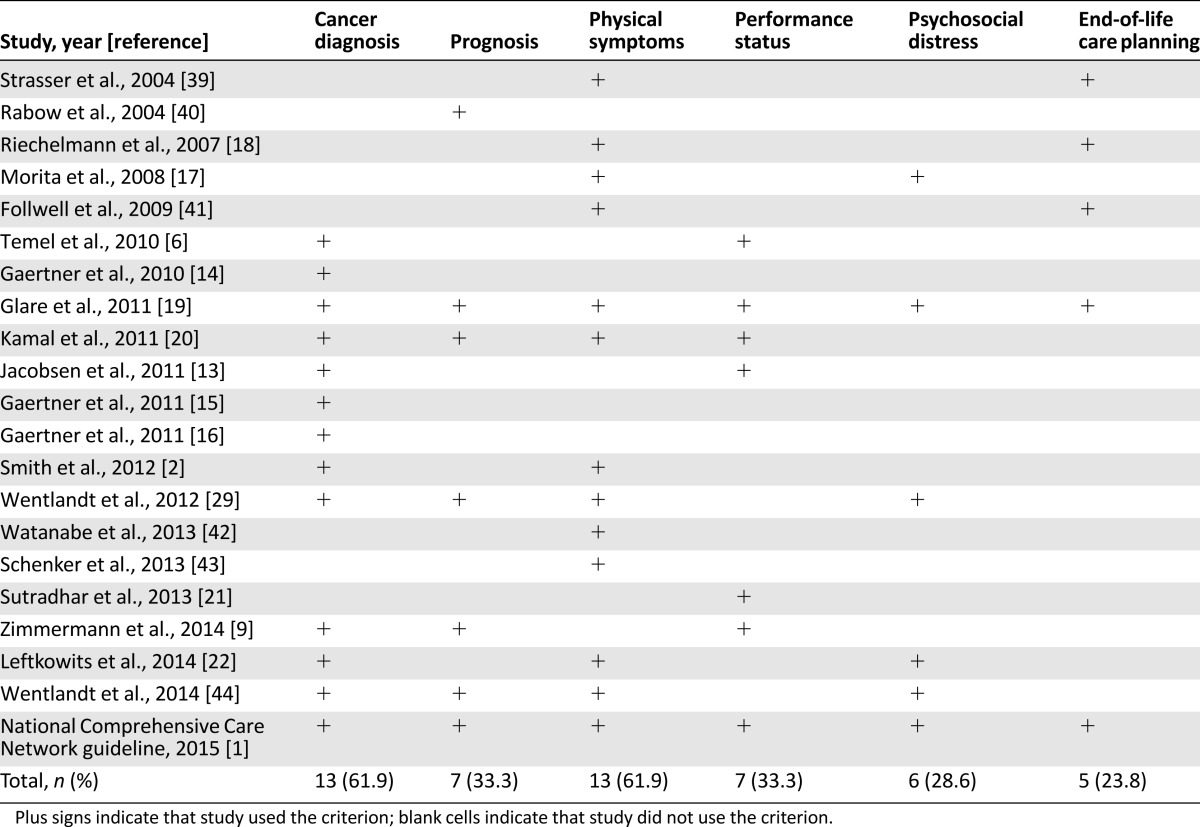

Six major categories for referral criteria were identified (Table 2), including physical symptoms (n = 13 [62%]), cancer diagnosis (n = 13 [62%]), prognosis (n = 7 [33%]), performance status (n = 7 [33%]), psychosocial distress (n = 6 [29%]), and end-of-life care planning (n = 6 [29%]).

Table 2.

Criteria for palliative care referral

Cancer Diagnosis/Trajectory

Although the diagnosis of an advanced cancer was the most commonly cited criterion, only 2 articles (n = 2 [9.5%]) [6, 13] specifically stated a time interval (i.e., within 8 weeks of diagnosis of metastatic lung carcinoma). The definition of advanced cancer varied among the 13 studies. Advanced disease was defined as metastatic disease in all 13 articles and also as locally advanced disease in 5 articles. Three studies (n = 3 [14.3%]) [1, 14, 15] further qualified that advanced cancer should be in the absence of curative treatment. Zimmerman et al. stated that advanced breast and prostate cancer should be hormonal refractory [9]. Gaertner et al. provided specific criteria for defining advanced cancer for 19 different tumor types [16].

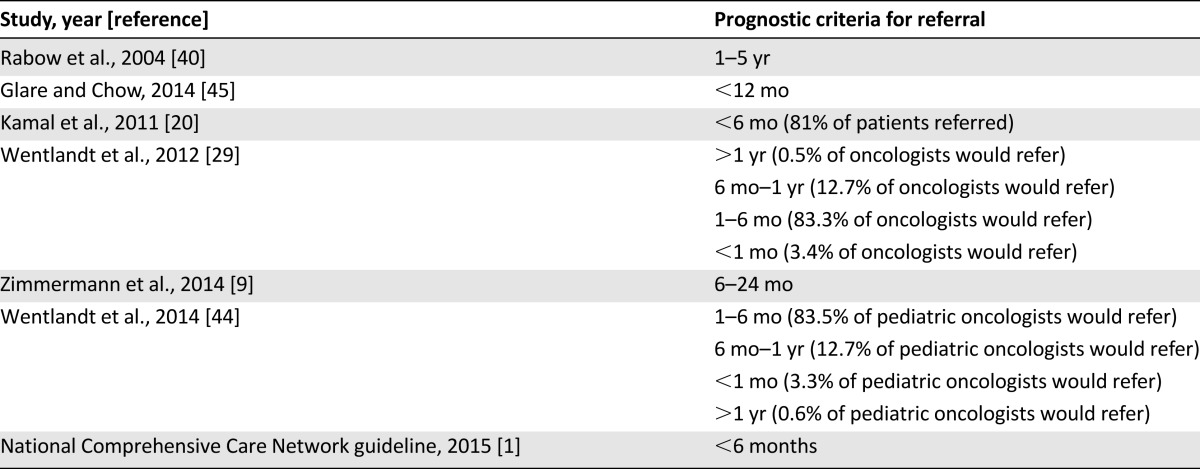

Prognosis

Prognosis was the third most common criterion quoted for palliative care referral. As shown in Table 3, the prognostic criteria for referral varied widely among the 7 articles. None of the articles suggested a standardized tool for prognostication.

Table 3.

Prognostic criteria for palliative care referral

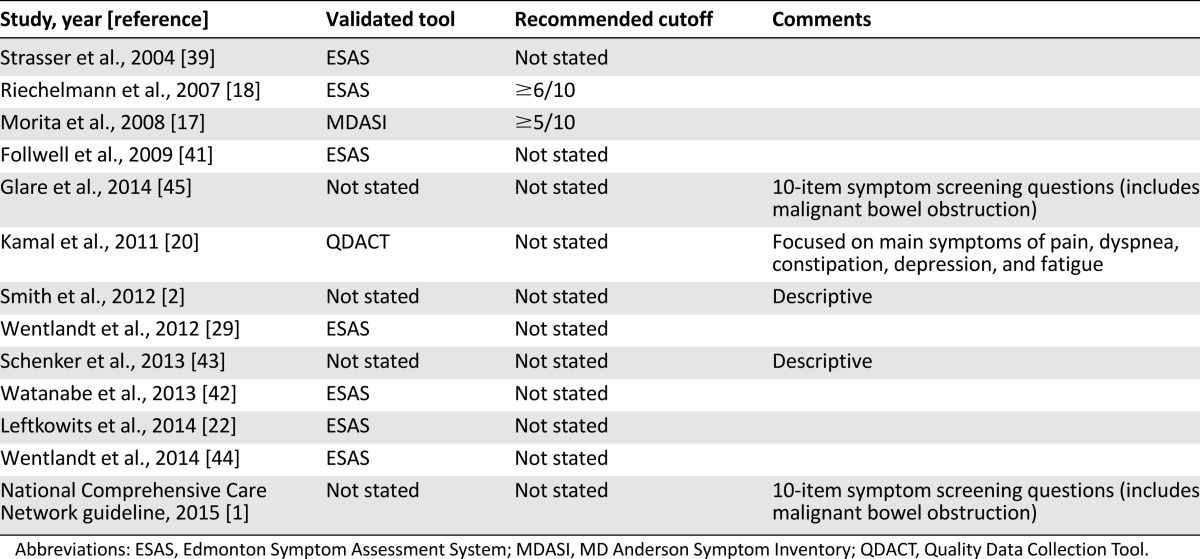

Physical Symptoms

Thirteen (61.9%) articles cited symptom management as reason for referral. Only 9 articles mentioned the validated tools for symptom assessment in the oncology setting, with 7 articles suggesting using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) (Table 4). Only 2 studies provided a cutoff for symptom severity before initiating a palliative care referral [17, 18].

Table 4.

Tools for assessment of physical symptoms

Performance Status

Seven articles (33.3%) cited performance status as one of the referral criteria. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline used a Karnofsky Performance Scale score of ≤50% and/or an Eastern Oncology Cooperation Group (ECOG) score of ≥3 as cutoffs [1]. Another 4 articles used ECOG performance status (cutoffs of 0–2 for 3; 1 study did not mention cutoff) [6, 9, 13, 19], and 2 other articles used the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) (1 article mentioned cutoff PPS score of <60%; the other article did not specify the cutoff) [20, 21].

Psychosocial Distress

Six (28.6%) articles quoted psychosocial distress as an indicator for referral, but only 2 (9.5%) articles indicated the tools for distress screening—both with the NCCN distress thermometer. NCCN guidelines recommended a distress score of 4 of 10 [1], whereas Morita et al. recommended a cutoff score of 6 or greater [17].

End-of-Life Care Planning

Five articles quoted end-of-life care planning as another reason for referral. However, these publications provided little further details on what encompassed end-of-life care planning.

Other Criteria

We identified 14 other criteria that were mentioned less commonly. These included patient request [1, 17, 19, 22], initiation of intravenous or tumor-specific chemotherapy [14–16], family concerns [1, 19], serious comorbidities [1, 19], and multiple hospitalizations [1, 20]. The remaining criteria were only suggested by the NCCN guideline once, including history of drug abuse, communication barriers, financial limitations, impaired cognitive function, frequent emergency visits, complicated intensive care unit admission, multiple allergy, request for hastened death, and caregiver stress.

Discussion

We systematically reviewed outpatient palliative care referral criteria, and we identified 20 unique criteria. Among these, there were 6 common themes for referral: 2 time-based criteria (cancer diagnosis/trajectory and prognosis) and 4 needs-based criteria (physical symptoms, performance status, end-of-life care planning, and psychosocial distress). We found no universally accepted criteria for which patients should be referred and when they should be referred. Findings from this study can inform the development of consensus-based referral criteria toward optimizing outpatient palliative care access.

Having a diagnosis of advanced cancer was clearly an important criterion for outpatient palliative care referral. Interestingly, the definition for advanced cancer varied widely among the articles. Thus, our study highlights the need to establish an operational definition for this commonly used term. Another important aspect relates to when patients with advanced cancer should be referred. Only a few stated that referral should occur shortly after cancer diagnosis [6]. For instance, the landmark randomized controlled trial from Temel et al. suggested that patients should be referred to palliative care within 8 weeks from the time of diagnosis of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, regardless of prognosis or need [6, 13]. Compared with patients who received only usual oncology care, those randomly assigned to receive concurrent early palliative care had improved outcomes; this finding highlights that palliative care involvement may be beneficial regardless of care needs. Despite the enthusiastic support for early specialist palliative care referral in clinical guidelines concurrent with primary palliative care delivered by oncology teams, referral is often initiated on the basis of patient needs instead of where the patient is along the disease trajectory in actual clinical practice. This discrepancy occurs partly because (a) existing palliative care programs often do not often have the necessary infrastructure to accommodate universal early referrals and (b) need-based referral is more intuitive to referring oncologists. Randomized trials are ultimately needed to directly compare both short- and long-term patient outcomes related to universal referral from the time of diagnosis of advanced cancer versus more selective referral based on patient needs. Our group is also conducting an international Delphi study to address the issue of who should be referred, balancing the limitations in existing evidence and clinical realities.

Despite the enthusiastic support for early specialist palliative care referral in clinical guidelines concurrent with primary palliative care delivered by oncology teams, referral is often initiated on the basis of patient needs instead of where the patient is along the disease trajectory in actual clinical practice.

Because prognosis varies widely among different cancer diagnoses, some investigators have proposed that the timing of referral should be disease specific. Gaertner et al. have published their institutional guidelines on disease-specific timing for integrating palliative care [16]; however, these criteria have not yet been fully validated or widely endorsed. Because life expectancy and palliative care needs vary widely, even among patients with the same cancer type (e.g., triple-negative breast cancer has a more aggressive disease course than other types of breast cancer), the decision for palliative care referral likely needs to be further personalized.

Prognosis is another commonly cited time-based criterion for outpatient referral. Similar to the advanced cancer diagnosis criterion, the optimal timing for referral based on prognosis has not been clearly defined. The main challenge with application of this criterion is that clinicians often overestimate survival with clinician prediction of survival and rarely use prognostic tools to augment their accuracy [23]. This could result in fewer eligible patients being referred. Encouragingly, the probabilistic question and the “surprise” question have recently been shown to be more accurate than the temporal question [24]. These questions may be particularly useful as triggers for palliative care referral (e.g., “What is the probability that the patient would be alive in 1 year?” If the clinician answered “30% or less,” the patient may be referred). Furthermore, novel bedside prognostic tools, such as phase angle, may improve the prognostic accuracy further [25].

Patients with physical or psychological distress are clearly candidates for palliative care referral. Successful application of these as referral criteria requires close collaboration between the oncology and palliative care teams to conduct routine symptom screening with validated questionnaire(s), a mechanism to trigger referral based on predefined cutoffs, and quality improvement programs to optimize the referral process. As shown in this study, the tools for distress screening have not been standardized. ESAS and the distress thermometer are two simple bedside tools that have been validated and adopted by several institutions [26, 27]. A randomized controlled trial that compared three types of distress screening (minimal screening vs. full screening vs. full screening plus psychosocial referral) found no difference in the level of distress at 3 months; however, patients in the full screening plus psychosocial referral group had lower distress scores and more referrals compared with the minimal screening group [28]. Moreover, psychosocial referral was associated with greater reductions in depression and anxiety. Ultimately, the cutoffs for referral may need to be individualized for each institution, depending on the tools used, the local availability of specialist palliative care, and the level of primary palliative care delivery by the oncology team [29–31]. Finally, for patients with predominantly psychological distress, there should be communication among the oncology team, palliative care, psychiatry, psychology, and social work services to coordinate the most appropriate team for management of these issues.

Performance status is also commonly considered as a referral criterion because it not only is a measure of daily function and care needs but also is strongly associated with prognosis and treatment eligibility [32–36]. Although randomized controlled trials supporting early palliative care included only patients with performance status of 0–1 [6, 9], it remains unclear whether an “enrichment” strategy that includes only patients who have greater care needs but not those already at the end-of-life (i.e., last 6 months) would result in greater benefits [21]. Thus, the optimal cutoff remains to be defined. Furthermore, the accuracy of performance status assessment has been questioned. A recent study at MD Anderson Cancer Center reported significant discrepancies between palliative care specialists and oncologists in their ECOG performance status ratings [37]. Thus, further research is needed to examine how performance status could be used to trigger referrals.

End-of-life care planning represents another category for referral. This encompasses a wide range of issues, such as discussing advance care plans, enhancing illness understanding and prognostic awareness, exploring further treatment options, establishing goals of care, and transitioning to hospice care. End-of-life discussions and early palliative care referral are both associated with improved quality of end-of-life care [38]. Outpatient palliative care clinics can play a particularly important role in facilitating these important discussions over time and helping patients refine their goals of care [10]. However, the optimal timing and nature of these interventions need to be further studied. For example, the need for hospice referral may not be an appropriate criterion for outpatient palliative care referral because patients should ideally be seen by the palliative care team much earlier in the disease trajectory than when hospice is needed. More research also needs to be conducted to determine how the need for end-of-life care planning can be operationalized as a trigger for referral, and similar to psychological distress, which team would be best to address each need.

End-of-life discussions and early palliative care referral are both associated with improved quality of end-of-life care. Outpatient palliative care clinics can play a particularly important role in facilitating these important discussions over time and helping patients refine their goals of care.

One important consideration is whether these criteria should be used alone or in conjunction with each other. Indeed, among the 21 articles, 17 (81%) mentioned 2 or more criteria for referral (Table 2). For example, the diagnosis of advanced cancer may be a necessary criterion for referral but may be insufficient to trigger a referral on its own. Glare et al. developed a screening tool based on the NCCN guideline to identify patients who may benefit from an outpatient palliative care referral. Advanced cancer diagnosis, performance status, prognosis, and symptom distress were assigned different weights, and all contributed to a composite score that ranged from 0 to 13; a score of 4 or more indicated a need for palliative care referral [19]. This scoring system requires additional time for screening and needs to be further validated in different institutions.

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, despite our updated search, we identified only 21 articles, suggesting that more research on outpatient palliative care and referral criteria should be conducted. Second, a minority of the articles (e.g., the NCCN guideline) did not indicate whether the criteria were specifically designed for outpatient palliative care only or for both inpatient and outpatient services. Thus, this may result in some degree of contamination because referral criteria for inpatients may be different. Third, we included the eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials of early outpatient palliative care as referral criteria, although they may not be specifically designed for this purpose. Finally, we focused only on the oncology population. Referral criteria for patients in other disease groups may be different.

Conclusion

Outpatient clinics are increasingly being recognized for their critical role in facilitating early palliative care access. Our systematic review highlighted the lack of consensus in the literature on which patients should be referred in the ambulatory setting. We found general agreement that cancer diagnosis, prognosis, physical symptoms, performance status, psychosocial distress, and end-of-life care planning needs should be considered when appropriate candidates are being identified. At the same time, more work is clearly needed to define the most appropriate assessment tools and optimal cutoffs for routine screening and referral. Referral criteria also need to be tailored to the local institution and to maximize outpatient palliative care access. Importantly, the use of standardized referral criteria should complement, instead of replace, clinical judgment to facilitate appropriate referrals.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

D.H. is supported in part by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (MRSG-14-1418-01-CCE) and a National Institutes of Health grant (R21CA186000-01A1).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: David Hui, Yimin Geng, Ron Hutchins, Masanori Mori, Florian Strasser, Eduardo Bruera

Provision of study material or patients: David Hui

Collection and/or assembly of data: David Hui, Yee-Choon Meng, Sebastian Bruera, Yimin Geng, Ron Hutchins

Data analysis and interpretation: David Hui, Yee-Choon Meng, Eduardo Bruera

Manuscript writing: David Hui, Yee-Choon Meng, Eduardo Bruera

Final approval of manuscript: David Hui, Yee-Choon Meng, Sebastian Bruera, Yimin Geng, Ron Hutchins, Masanori Mori, Florian Strasser, Eduardo Bruera

Disclosures

Florian Strasser: Sunstone, ONO, Danone, Helsinn, Vifor, Prime Oncology (C/A), Helsinn (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Levy MH, Smith T, Alvarez-Perez A et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: palliative care. 2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed March 29, 2016.

- 2.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizzo PA, Walker DM, Bomba PA, et al. Washington, DC: Insitute of Medicine; 2015. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:159–171. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KL, et al. Impact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2012;17:1574–1580. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:459–464. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Scheicht D, et al. Implementing WHO recommendations for palliative care into routine lung cancer therapy: A feasibility project. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:727–732. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaertner J, Wuerstlein R, Klein U, et al. Integrating palliative medicine into comprehensive breast cancer therapy - a pilot project. Breast Care (Basel) 2011;6:215–220. doi: 10.1159/000328162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Hallek M, et al. Standardizing integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer therapy–a disease specific approach. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1131-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morita T, Fujimoto K, Namba M, et al. Palliative care needs of cancer outpatients receiving chemotherapy: An audit of a clinical screening project. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riechelmann RP, Krzyzanowska MK, O'Carroll A, et al. Symptom and medication profiles among cancer patients attending a palliative care clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1407–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glare PA, Semple D, Stabler SM, et al. Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: Evaluation of a practical set of referral criteria. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:366–370. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal AH, Bull J, Kavalieratos D, et al. Palliative care needs of patients with cancer living in the community. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:382–388. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutradhar R, Seow H, Earle C, et al. Modeling the longitudinal transitions of performance status in cancer outpatients: Time to discuss palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:726–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefkowits C, W Rabow M, E Sherman A, et al. Predictors of high symptom burden in gynecologic oncology outpatients: Who should be referred to outpatient palliative care? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327:195–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui D, Kilgore K, Nguyen L, et al. The accuracy of probabilistic versus temporal clinician prediction of survival for patients with advanced cancer: A preliminary report. The Oncologist. 2011;16:1642–1648. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui D, Bansal S, Morgado M, et al. Phase angle for prognostication of survival in patients with advanced cancer: Preliminary findings. Cancer. 2014;120:2207–2214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999;13:113–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson LE, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, et al. Screening for distress in lung and breast cancer outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4884–4891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, et al. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4380–4386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison RS, Augustin R, Souvanna P, et al. America’s care of serious illness: A state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation’s hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1094–1096. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.9634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward AM, Agar M, Koczwara B. Collaborating or co-existing: a survey of attitudes of medical oncologists toward specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23:698–707. doi: 10.1177/0269216309107004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang RB, Hu WY, Chiu TY, et al. Prediction of survival in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan: Constructing a prognostic scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltoni M, Pirovano M, Scarpi E, et al. Prediction of survival of patients terminally ill with cancer. Results of an Italian prospective multicentric study. Cancer. 1995;75:2613–2622. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2613::aid-cncr2820751032>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau F, Maida V, Downing M, et al. Use of the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) for end-of-life prognostication in a palliative medicine consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: A prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jang RW, Caraiscos VB, Swami N, et al. Simple prognostic model for patients with advanced cancer based on performance status. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e335–e341. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YJ, Hui D, Zhang Y, et al. Differences in performance status assessment among palliative care specialists, nurses, and medical oncologists. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1050–1058.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strasser F, Sweeney C, Willey J, et al. Impact of a half-day multidisciplinary symptom control and palliative care outpatient clinic in a comprehensive cancer center on recommendations, symptom intensity, and patient satisfaction: A retrospective descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:481–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Follwell M, Burman D, Le LW, et al. Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe SM, Fairchild A, Pituskin E, et al. Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: report of a pilot project. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1201–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e37–e44. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, et al. Referral practices of pediatric oncologists to specialized palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2315–2322. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glare PA, Chow K. Validation of a simple screening tool for identifying unmet palliative care needs in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;11:e81–e86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]