Abstract

Objective:

To ascertain the trend of poisoning cases admitted to the Government District Headquarters Hospital, a secondary care center in Udhagamandalam, Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu, India, over a five-year period.

Materials and Methods:

The number of cases that presented to the hospital annually (incidence, mortality, and case fatality rates), socio-demographic pattern, and the nature of the poison were noted.

Results:

A total of 1860 poisoning cases (80 deaths) were reported during the period from October 2008 to September 2013. The incidence of poisoning was found to increase every year. The average incidence was 1.60 per 1000 population, while the average case fatality rate and mortality rates were 40.51 and 0.07, respectively. A total of 1148 (62%) were males. The majority of cases were seen in the 21-30 age group (41.24%). The poisonings were largely deliberate self-harm (n = 1,755; 94.35%), followed by accidental (n = 85; 4.57%). Agrochemicals were the main choice of poisoning agents and among these, organophosphates were the major cause.

Conclusion:

The data generated can help policy makers take decisions on the sale and availability of pesticides in this region.

KEY WORDS: Choice of poison, mortality rate, Nilgiris population, organophosphate poisoning, surveillance

Introduction

Pesticide poisoning is a dominant source of mortality and morbidity across the world.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that globally more than 200,000 people die of pesticide poisoning. Lifestyle changes as well as changing social frameworks are the major reasons for the increased incidence of poisoning cases.[2] Apart from this, easy availability, low-cost and unrestricted sale of pesticides are the other key reasons.[3,4] A high incidence of pesticide poisoning is usually associated with socio-demographic pattern of the population and limited pesticide regulation.[5,6] We thus conducted a hospital-based study to assess the pattern of pesticide poisoning in this region.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (JSSCP/DPP/IRB/009/2013-14 dated on 05/09/2013) who also granted a consent waiver. All data were coded with unique identifiers and kept confidential.

Study site

Udhagamandalam is the capital of the Nilgiris District, situated in the state of Tamil Nadu in the Western Ghats of Southern India, and has a population of 233,374.[7] The town's economy is mainly derived from tourism and agriculture.

Study design

A retrospective analysis of data from October 2008 to September 2013.

Study procedure

From the medical records, information regarding age, gender, marital status, manner of poisoning, religion, diurnal variation in poisoning, and the causative agents for poisoning of patients admitted was gathered. Exclusions were food poisoning and snake bites. Cow dung dye, commonly used synthetic floor cleaning agent in the Southern region of India which is identified in green and yellow colours composed of malachite green and auramine –O respectively, were included as poisoning agents in the study. Physicians determined the causative agent based on the residue in the container/packet brought along with the patients and/or the circumstances from the patient's caretakers and/or the clinical manifestations of the patients.

Statistical analysis plan

Incidence, case fatality, and mortality rates were calculated from the collected data using the following formulae.[8]

Incidence rate = (Number of new cases of a disease occurring in the population during a specific period of time ÷ Number of persons who are at risk of developing the disease during that period of time) × 1000.

Mortality rate = (Number of deaths occurring during a period of time ÷ Size of the population among which deaths occurred) × 1000.

Case fatality rate = (Number of individuals dying during a specified period of time due to a specific condition ÷ Number of individuals affected with that condition) × 1000.

The chi-square test was used to assess association between descriptive measures on occurence of poisoning and death due to poisoning. A P value ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data obtained in this study were analyzed through the software GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows.

Results

Demographics

A total of 1860 poisoning cases were reported with 80 (4.30%) deaths. The majority of poisoning cases were male (n = 1,148; 61.72%). The average incidence rate was 1.6 per 1000 population. The average case fatality and mortality rates were found to be 40.51 and 0.07, respectively. Higher mortality and case fatality rates were seen during 2012-2013. The annual distribution of poisoning cases and mortalities are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demography and annual occurrence of poisoning cases and mortalities

| Descriptive measures | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of poisoning | 278 | 301 | 361 | 447 | 473 |

| Number of deaths | 9 | 6 | 16 | 19 | 30 |

| Incidence rate (Per 1000 population) | 1.19 | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.92 | 2.03 |

| Case fatality rate | 32.37 | 19.93 | 44.32 | 42.50 | 63.42 |

| Mortality rate | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Male | 171 | 183 | 232 | 270 | 292 |

| Female | 107 | 118 | 129 | 177 | 181 |

| P = 0.8386 | |||||

| Married | 175 | 210 | 257 | 300 | 310 |

| Unmarried | 103 | 91 | 104 | 147 | 163 |

| P = 0.1724 | |||||

| Suicidal | 263 | 290 | 338 | 417 | 447 |

| Accidental | 10 | 7 | 16 | 27 | 25 |

| Undetermined | 5 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| P = 0.0641 | |||||

| Day | 108 | 124 | 149 | 165 | 171 |

| Night | 170 | 177 | 212 | 282 | 302 |

| P = 0.4503 | |||||

| Hindu | 237 | 264 | 315 | 395 | 443 |

| Muslim | 18 | 19 | 39 | 34 | 16 |

| Christians | 23 | 18 | 7 | 18 | 14 |

P = 0.0001

Univariate analysis

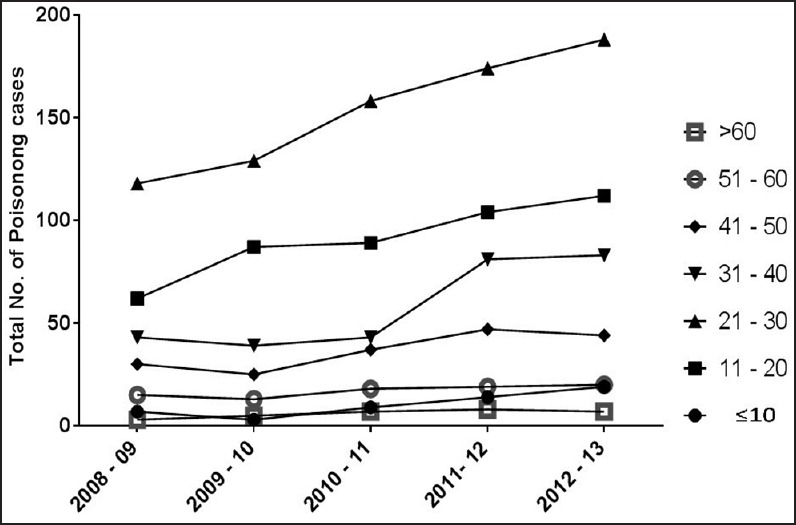

The mortality rate was higher among married men (40.75%). The highest incidence was seen among young adults within the age group of 21-30 years (n = 767; 41.24%), followed by the age group 10-20 years (n = 454; 24.57%). Fewer cases were observed at the extremes of age (patients of less than 10 years of age [2.79%] and more than 60 years of age [1.61%]). A significant association was found between age and the fatality rate (P = 0.0013). The occurrence of poisoning fatalities as per age (in years) was in the following order 21-30 (6.52%) > 10-20 (3.96%) > 31-40 (3.46%) > 41-50 (1.10%). The year-wise poisoning fatality event is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Year wise distribution of poisoning cases as per age group

Deliberate self-harm was found to be the most common reason for poisoning (n = 1755, 94.35%) with accidental poisoning seen only in (n = 85) 4.57% cases. In the remaining 20 cases (1.08%), the intention was unknown. A significant correlation was observed between the intention of poisoning and the fatality rate (P < 0.0001). The death rate was found to be the highest among the undetermined category (30%), followed by accidental (21.18%), and suicidal intent (3.19%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Estimates of fatality among survey population

| Category | Number of survivors (n) | Number of deaths (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1094 | 54 | 1148 |

| Female | 686 | 26 | 712 |

| P = 0.2770 | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| <10 | 52 | 0 | 52 |

| 10-20 | 436 | 18 | 454 |

| 21-30 | 717 | 50 | 767 |

| 31-40 | 279 | 10 | 289 |

| 41-50 | 181 | 2 | 183 |

| 51-60 | 85 | 0 | 85 |

| >60 | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| P = 0.0013 | |||

| Suicidal | 1699 | 56 | 1755 |

| Accidental | 67 | 18 | 85 |

| Undetermined | 14 | 6 | 20 |

P = 0.0001

Poisoning was seen higher among Hindus (n = 1,654; 88.92%), followed by 126 Muslims (6.77%) and 80 Christians (4.30%). The time of presentation to the hospital was most commonly night (1,143; 61.45%), followed by day (717; 38.55%).

Choice of agents used for poisoning

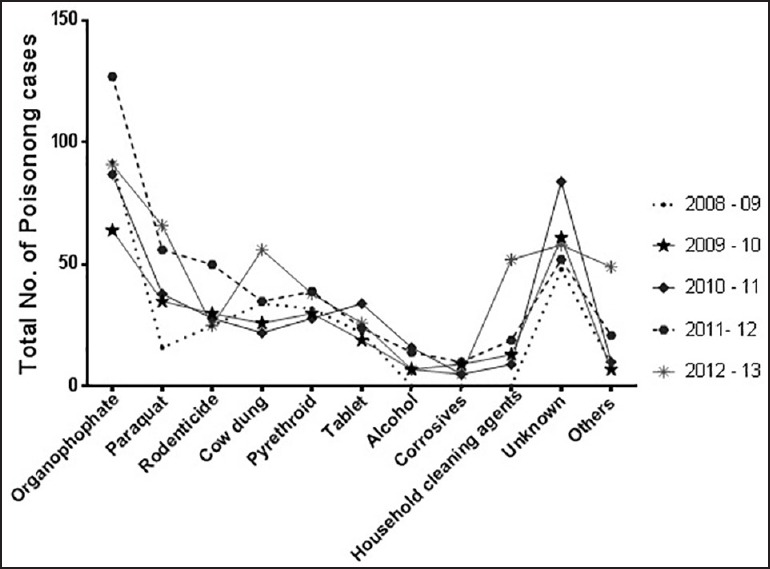

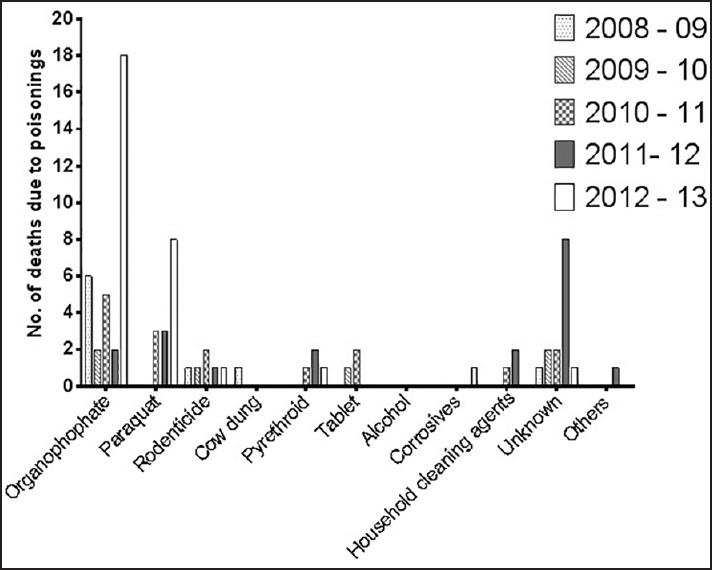

The agents were classified into 11 categories according to their properties as shown in Table 3. Among these agents, organophosphates, paraquat, rodenticide, and pyrethroid were various types of agrochemicals. The agents used for the poisoning that could not be identified were termed as “unknown” while agents like eucalyptus oil, carbon monoxide, turpentine oil, ink, and stick gum used for poisoning were collectively termed “others.” The graphical representation of the various agents and their year-wise usage for poisoning is given in Figure 2. Among agrochemicals, organophosphate compounds were more frequent causes (24.78%) and also caused more fatalities (n = 33), followed by unknown poisoning (16.29%, number of deaths: 14) and paraquat poisoning (11.34%, n = 14). The number of deaths due to various poisoning agents is shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Poisoning agents used and related death for 5-year study period

| Agent | Total number of poisonings | Percentage of poisoning (%) | Total number of deaths | Percentage of death (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates | 461 | 24. 78 | 33 | 7.16 |

| Paraquat | 211 | 11.34 | 14 | 6.64 |

| Rodenticides | 158 | 8.49 | 6 | 3.80 |

| Cow dung dye | 173 | 9.30 | 1 | 0.58 |

| Pyrethroid | 167 | 8.98 | 4 | 2.40 |

| Tablets | 125 | 6.72 | 3 | 2.40 |

| Alcohol | 44 | 2.37 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Corrosives | 29 | 1.56 | 1 | 3.45 |

| Household cleaning agents | 93 | 5.00 | 3 | 3.23 |

| Unknown | 303 | 16.29 | 14 | 4.62 |

| Others | 96 | 5.16 | 1 | 1.04 |

Figure 2.

The total number of reported poisoning cases

Figure 3.

Fatality associated to poisoning agent, a year-wise profile

Discussion

The present study examines the incidence, mortality, and case fatality rates among patients presenting with poisoning in one hospital in Southern India. The availability of other public hospitals in the Nilgiris District reduces the chances of admission of patients those who are not belonging to Udhagamandalam region to this study site. The cases of immediate death at spot due to poisoning (intentional or unintentional) are also admitted to the emergency unit of the same study center for the postmortem analysis, as this hospital is the only center for that. Such data were also included in the study.

We found an increase in incidence, mortality, and case fatality rate with successive years. This is limited by the assumption that patients that presented to us are representative of all those with poisonings in our local population. The mortality rate indicates the extent of death happening due to severe poisoning and conditions in which there was difficulty in early detection of the used agent.[9] For instance, physicians may find it difficult to detect the exact chemical class of the pesticide used due to a large variety of brands available in the market.[10] We found the average incidence rate of self-poisoning cases in this population is 1.60 per 1000 population, whereas the incidence rate of self-poisoning given by the WHO for Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Central America (El Salvador and Nicaragua) were 1.8, 0.178, and 0.35 per 1000 respectively.[11] Further, the death because of self-poisoning is less than the accidental poisoning which is different from earlier reports from the country.[12]

Financial burden, family disharmony, and stress could be the reasons for the increased rate of poisoning among married people.[5,12,13] The same may also be interpreted and considered as the reason for the largely male preponderance. The occurrence of poisoning cases is more among younger population (between 21-30 years) as this is comparable to studies conducted in other parts of India and may be due to the high stress and other pressures in this age group.[5,12,13,14] The larger number of poisoning reported in the Hindu community is in all likelihood due them forming a large part of the population. Religion prohibits intentional poisoning among Muslims.[5,12]

The majority of the patients consumed poison during the night which may be due to their intention to avoid the attention of others.[5] A total of 105 poisonings were preventable and these can be addressed.

Conclusion

Psychological guidance programs are known to decrease the depression levels by developing personal skills, including self-esteem and problem-solving capacity.[15] This could be a remedial measure for survivors. As India is an agricultural country, many people have access to agrochemicals that could lead to both deliberate and accidental poisoning.[12] The high death rate due to organophosphate compounds is similar to the rate with “unknown” poisoning cases. Easy access to these potent agents could be the possible explanation for this condition.[12,13,16]

The study is limited by being retrospective, and being a single center study, though two smaller hospitals are functioning in this district. Also, cases admitted to private hospitals were not captured (though medicolegal cases would have eventually been referred). As Nilgiris is a hill station with a population of about 0.234 million, this report may not reflect the country's actual enormity of the problem. The study does show that poisonings and mortality due to poisonings is a significant problem. Regulations regarding the sale of agrochemicals by policy makers along with psychological guidance would go a long way in addressing the problem.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Government Headquarters Hospital, Udhagamandalam. Authors also acknowledge the Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India, for providing Inspire Fellowship to the first author (Ms. T H Indu, Research Scholar, JSS University, Mysore, India).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Srinivas Rao CH, Venkateswarlu V, Surender T, Eddleston M, Buckley NA. Pesticide poisoning in South India: Opportunities for prevention and improved medical management. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:581–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh B, Unnikrishnan B. A profile of acute poisoning at Mangalore (South India) J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh PS, Aggarwal AD, Oberoi SS, Aggarwal KK, Thind SA, Buller SD, et al. Study of poisoning trends in North India — A perspective in relation to world statistics. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013;20:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam MN, Islam N. Retrospective study of 273 deaths due to poisoning at Sir Salimullah Medical College from 1988 to 1997. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2003;5:129–31. doi: 10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanchan T, Menezes RG. Suicidal poisoning in Southern India: Gender differences. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Zhou L, Zheng N, Zhuo L, Liu Y, Liu L. Poisoning deaths in China: Type and prevalence detected at the Tongji Forensic Medical Center in Hubei. Forensic Sci Int. 2009;193:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.“Udhagamandalam,” Census. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.census2011.co.in/census/metropolitian/450-Udhagamandalam.html .

- 8.Hisham M, Vijayakumar A, Rajesh N, Sivakumar MN. Auramine-o and malachite green poisoning: Rare and fatal. Ind J Pharm Pract. 2013;6:72–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordis L. 4th ed. Saunders: Elsevier; 2009. Epidemiology; pp. 37–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeyaratnam J, de Alwis Seneviratne RS, Copplestone JF. Survey of pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:615–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thundiyil JG, Stober J, Besbelli N, Pronczuk J. Acute pesticide poisoning: A proposed classification tool. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:205–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.041814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanchan T, Menezes RG, Kumar TS, Bakkannavar SM, Bukelo MJ, Sharma PS, et al. Toxicoepidemiology of fatal poisonings in Southern India. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17:344–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkar D, Shaheduzzaman M, Hossain MI, Ahmed A, Mohammad N, Basher A. Spectrum of acute pharmaceutical and chemical poisoning in northern Bangladesh. Asia Pac J Med. Toxicol. 2013;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soltaninejad K, Faryadi M, Sardari F. Acute pesticide poisoning related deaths in Tehran during the period 2003-2004. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007;14:352–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aseltine RH, Jr, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:446–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawson AA, Mitchell I. Patients with acute poisoning seen in a general medical unit (I960-71) Br Med J. 1972;4:153–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5833.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]