Abstract

Background:

Hodgkin's lymphoma displays distinct epidemiological attributes in Asian population thus making it relevant to study whether there are any differences in treatment outcomes too when treated with current standard of care.

Aim:

To evaluate the treatment outcomes of de-novo advanced stage HL in adults.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective study included de-novo advanced stage HL patients (≥15 years) registered at our center from January 2004 to December 2007. Treatment outcomes were measured in terms of response rates, overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Overall and PFS were calculated with Kaplan-Meier methodology and Cox-proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis to identify prognostic factors.

Results:

There were 125 patients (males 77%) who received minimum one cycle of chemotherapy with median age of 32 years (Range 15-65 years). Stage IV disease was seen in (46 patients) 37%; 75% (94 patients) patients had B symptoms. International prognostic score (IPS) ≤4 was seen in 95/112 (85%) patients. ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) chemotherapy was given to 94%. Radiation to residual/bulky sites was given to 36% (45 patients). Response data was available for 112 patients; complete response in 76%; partial response in 10 % and progressive disease in 3 patients. Nineteen deaths (progressive disease-7, toxicity-8, unrelated cause-4) were observed. At median follow-up of 28 months, estimated 5-year OS and PFS were 60% and 58%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, IPS and response to treatment were significant factors for both OS and PFS.

Conclusions:

The treatment outcomes in this study are comparable with the published literature with limited follow-up data.

KEY WORDS: Advanced stage, Hodgkin's lymphoma, India, outcomes

Introduction

Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) is a rare B-cell neoplasm which constitutes approximately 11% of all lymphoid malignancies in the western world.[1,2] Over last three decades efforts of various cooperative groups from developed countries have made HL one of the most curable malignancies in adults. The treatment is based upon staging (Ann Arbor staging), clinico-radiological and laboratory parameters (risk factors) which help categorizing the patients into early favorable, early unfavorable and advanced stage disease. Approximately 90% of patients with early stage disease are cured when treated with combined modality treatment whereas various chemotherapy regimens can cure 65-85% of patients with advanced stage disease.[3] Approximately 20% of all patients fail to respond to available therapies and succumb due to disease. On the other hand a small proportion of patients who have good outcomes with with HL experience long-term side effects like cardiovascular diseases, infertility and second cancers.[4] Thus efforts are to maximize outcomes with minimum toxicity by early identification of poor players and the good ones.[5,6,7]

The major drawback of the available data in HL is its applicability in developing countries given the poor representation of patients from developing countries in clinical trials which have shaped current management. It seems relevant to have the knowledge of treatment outcomes in our patients with the same regimens which are considered as current standard of care, as several studies have highlighted important differences in Indian patients with respect to epidemiology (lower incidence and lack of bimodal peak), pathology (higher frequency of mixed cellularity) and pathogenesis (lower EBV positivity).[8] In addition regimens like escalated BEACOPP which result in 85% cure rates in advanced HL, will have very limited applicability in developing countries due to cost and toxicity concerns. As the available data on treatment outcomes of advanced HL in adults from India is limited we decided to conduct a retrospective analysis of data from our tertiary care centre to assess the efficacy of available therapies.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective case record-based observational study included patients aged ≥15 years, with Stage III and IV de-novo HL, who were registered in the lymphoma clinic at our hospital from January 2004 to December 2007. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution and waiver of consent was granted. Data confidentiality was maintained. Electronic medical records and case records were reviewed for demographic details, clinical features including B symptoms and bulky disease sites, laboratory results (ESR, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, absolute lymphocyte count, LDH, albumin), imaging including type of study (CT scan or plain radiograph of chest and ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis) and disease sites, bone marrow biopsy involvement. Histopathological diagnosis including subtype of HL was recorded. Available parameters were used for staging and risk stratification (international prognostic score). Records were evaluated for details of therapy, including chemotherapy regimen, number of chemotherapy cycles, second and subsequent lines of treatment, if any and radiation. The response (interim and end of therapy) to each line of treatment and method for response assessment was recorded from the charts. Patient's disease status till the last follow up was recorded along with date of relapse and/or death. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (OS). The secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and response rates. OS was calculated from date of diagnosis to death due to any cause or last follow-up. PFS was calculated from date of diagnosis to date of relapse/progression or death due to any cause. Responses were classified according to the proposed International Workshop Criteria.[9]

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were plotted with Kaplan–Meier methodology. Cox-proportional hazards model was used to analyze the prognostic effect of variables like age, international prognostic score and end of therapy response on OS and PFS. Patients who were lost to follow up after therapy were censored as alive at their last follow up. Patients who had disease progression or had only partial response at the end of therapy and were lost to follow up were censored as progressed and dead at their last available follow up. Descriptive statistics was used for analysis of demographic variables, disease characteristics and response rates.

Results

Demographics

A total of 165 cases were retrieved from lymphoma clinic database. Forty patients were either lost to follow up after initial work up or did not take treatment at our centre and thus were not included in analysis. Thus, data of 125 patients who had received at least one cycle of chemotherapy at our center was analyzed.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of these 125 patients were comparable to those 40 patients who did not take treatment at our center. The median age was 32 years (range 15-65 years) and 77% were males. Approximately 25% of the patients were above 45 years of age. B symptoms at diagnosis were recorded in 76% of the patients. Approximately 16% of the patients had received anti-tubercular therapy for their symptoms prior to the histological diagnosis of HL — the most common misdiagnosis in these patients. Sixteen percent of the patients had co-morbidities. Majority (97%) of the patients had ECOG performance status (ECOG-PS) of ≤2. Stage III disease was seen in 63%. Bone marrow involvement was seen in 15% patients and 37% patients had one or more extra-nodal sites of disease. Bulky disease (defined as largest tumor size ≥7 cm)[10] was seen in 52% patients. The most common histopathology was mixed cellularity, seen in 57%, followed by nodular sclerosis, lymphocyte predominant and NOS types, in 32%, 2% and 9%, respectively.

International prognostic score (IPS) could be estimated in 112 patients (due to non-availability of complete data). IPS score ≤4 was seen in 85 % (95/112) of the patients. Four patients had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) at the time of diagnosis.

Treatment

Most of the patients 118 patients (94%) were treated with ABVD, while 6% patients received COPP regimen, due to advanced age or co morbidities. Six cycles of chemotherapy were completed by 90% of the patients give actual number. Radiation was given to 36% give actual number of the patients for either bulky sites or residual disease at the end of chemotherapy.

Outcomes

Among these 125 patients who were treated; response data was available in 90% (112/125) of the patients. The complete response (CR) rate was 76% (96/125), partial response (PR) was seen in 10% patients (13/125), and three patients had disease progression on treatment. Of the 13 patients who were not evaluated, 5 patients died during treatment period, all deaths were due to treatment-related toxicities, 8 patients were lost to follow up during therapy.

There were 19 deaths, of which 10 were late deaths (deaths after completion of treatment) and 9 were early deaths (death while on treatment). Seven deaths were related to progressive disease, 8 were related to toxicities, and 4 were due to unrelated causes. Forty-two patients experienced progressive disease or relapse; salvage therapy details were available on 24 patients (Salvage chemotherapy alone-19, autologous stem cell transplant-2, best supportive care alone-2 and radiation with palliative intent-1).

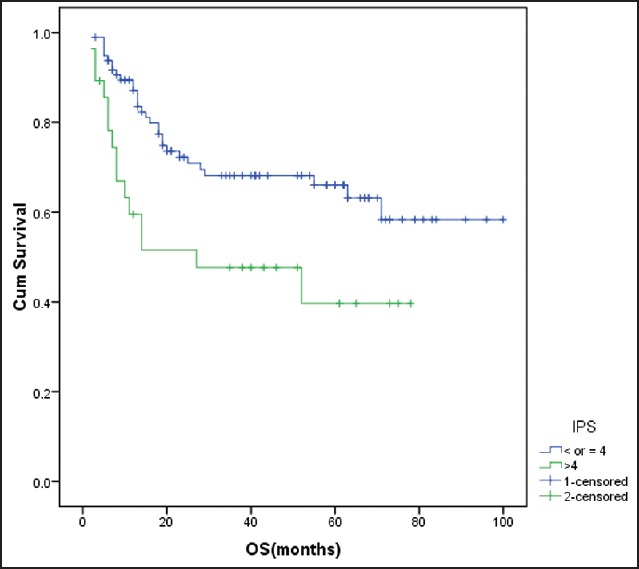

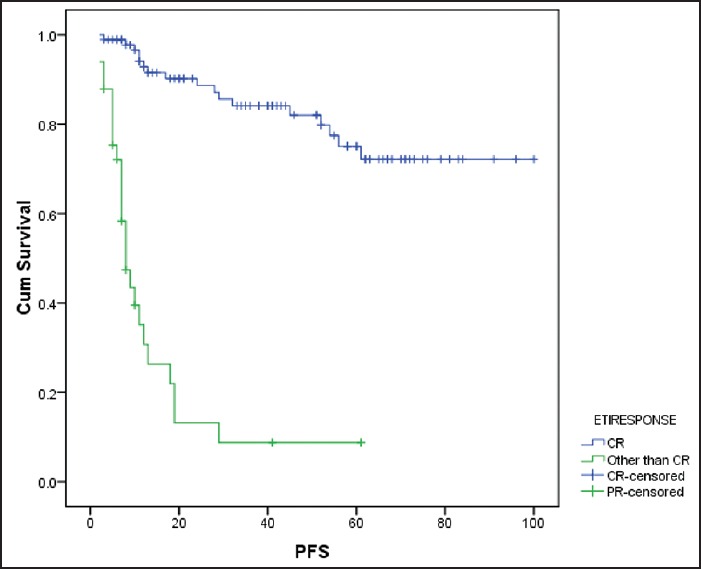

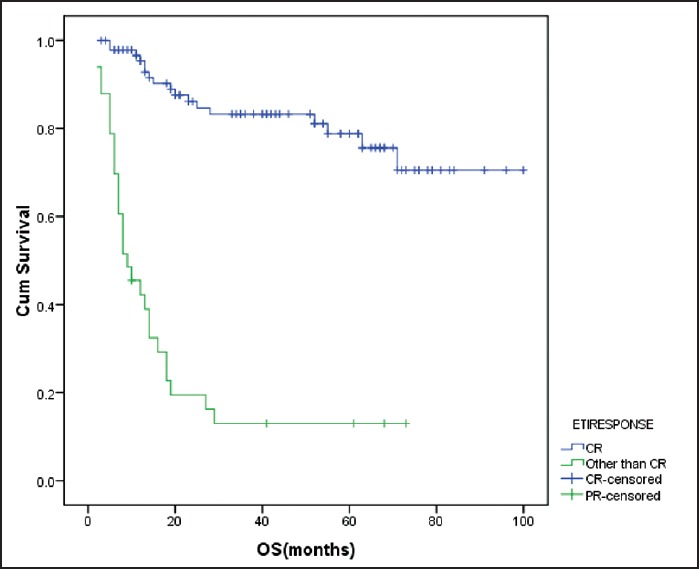

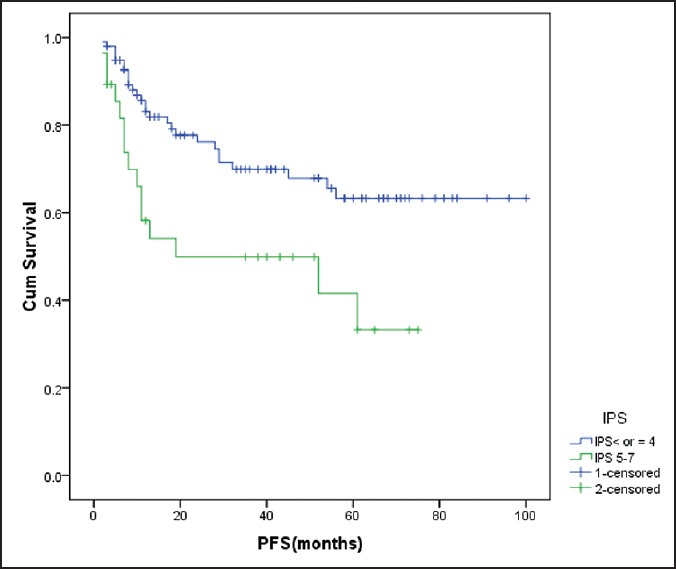

Forty percent (55/125) patients remain on follow up till the time of analysis (December 2013). With a median follow up of 28 months (2-100 months), the estimated 5-year OS and PFS were 60% and 58%, respectively. On univariate and multivariate analysis IPS (>4), age (>45 years), and end of therapy response (failure to achieve complete response) adversely affected the OS, whereas only IPS >4 and end of therapy response showed negative impact on the PFS, Figures 1–4. Disease bulk and baseline albumin levels did not have any impact on OS or PFS.

Figure 1.

Impact of international prognostic score on overall survival IPS >4 was associated with inferior overall survival (P = 0.01) cum Survival - Cumulative survival

Figure 4.

Effect of end of treatment response on progression-free survival failure to achieve CR was associated with shorter progression-free survival (P < 0.001) cum survival - cumulative survival

Figure 2.

Effect of end of treatment response on overall survival failure to achieve CR after chemotherapy adversely influenced overall survival (P < 0.001) cum survival - cumulative survival ETIRESPONSE - End of treatment response

Figure 3.

Influence of international prognostic score on progression-free survival High IPS (>4) was associated with shorter progression-free survival (P = 0.006) cum survival - cumulative survival ETIRESPONSE - end of treatment response

Discussion

This single-center study attempts to provide a perspective on outcomes of adult advanced HL treated with ABVD regimen. Among a total of 687 cases of HL seen in our institute from January 2004 to December 2007, advanced stage HL represented 24% of the total cases. This is in contrast to studies reported by Chandi et al.[8] and Vashisht et al.[11] where advanced stage disease represented 67% and 53% of the total cases, respectively. The median age at presentation was 32 years, with a male preponderance which is similar to other studies from India.[8,12,13] Our study, similar to other Indian studies have reported high male preponderance (77%). The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data reports an overall high incidence in males, but more females are affected in the 20-34 year age group.[14] The reason for this gender distribution in India is not known, and is probably due to higher incidence of the mixed cellularity histological type and referral bias. Peripheral adenopathy was present in 92% cases at baseline, most common site being cervical nodes, similar to study reported by Chandi et al.[8] and Ultman et al.[15] Almost 3/4th of patients had B symptoms as compared to 25% in the other studies from developed world. This may indicate a higher disease burden at diagnosis. Bulky disease was seen in 42% of the patients in the present study which is lesser as compared to the study conducted in advanced stage HL by Diehl et al. (58-68%).[16] The most common histologic subtype was mixed cellularity in our patients, constituting 57% of our cases. Other Indian studies have also reported higher frequency of mixed cellularity subtype in 55-70% of cases.[8,11,12,13,17] A significant proportion of patients with HL in India are misdiagnosed as tuberculosis based on clinical features and fine needle aspiration cytology and are treated with antitubercular therapy for a long period before the histological diagnosis is made. This is evident in our study; 16% of patients had received antitubercular therapy prior to being diagnosed as HL.

The CR rates with ABVD regimen reported in the literature range from 68% to 92%, the largest of which is the U.S intergroup trial wherein CR rate was 76% and progressive disease was seen in 2.1% patients.[18] In our study, the results were comparable with a CR in 76% of patients and disease progression seen in 2.4% patients. The reported 5-year PFS ranges from 61% to 80% and 5-year OS ranges from 73% to 90% in the various trials.[18,19,20,21] In our study the estimated 5-year PFS and OS were 58% and 60%, respectively. OS in Hodgkin's lymphoma is influenced by the subsequent salvage regimen used, the inferior OS in our study could be explained by the fact that only two patients underwent autologous stem cell transplant. On multivariate analysis, we found that OS was affected by age, IPS and response to therapy, while PFS was affected by IPS and response to therapy.

ABVD is widely accepted as a standard treatment option for advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma, and this study shows that comparable results can be reproduced in our patients with acceptable tolerance. However, as the long-term data from one study revealed a failure-free survival of 47% and OS of 59% at 14.1 years of follow up, it is being realized that ABVD is a good regimen, but there is a need to improve on the results.[22] Two options have been explored to improve the OS, intensifying the therapy upfront with a regimen like escalated BEACOPP or improving the salvage therapy.[23] The tolerance to such an intensive regimen in a resource constraint setting remains to be seen.

The strength of this study lies in the fact that this is the largest data from India on advanced stage HL treated with ABVD regimen. However, this is a retrospective analysis with its inherent flaws of missing data, lack of a uniform methodology for response assessment, recording toxicity and lack of follow up in more than half of patients.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Mrs Preeti Pawaskar for her help in data collection and Mr Nitin Solanki for retrieving the case record files.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Storm HH. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. I to VIII IARC Cancer Base No. 7; pp. 672–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ries LA, Harkins D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2003. Bethesda, (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horning JS. Hodgkin's Lymphoma. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Niederhuber JE, Kastan MB, McKenna WG, editors. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2008. pp. 2353–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björkholm M, Axdorph U, Grimfors G, Merk K, Johansson B, Landgren O, et al. Fixed versus response-adapted MOPP/ABVD chemotherapy in Hodgkin's disease. A prospective randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:895–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisselbrecht C, Ferme C. Prognostic factors in advanced Hodgkin's disease: Problems and pitfalls. Towards an international prognostic index. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;15(Suppl 1):23–4. doi: 10.3109/10428199509052700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straus DJ. High-risk Hodgkin's disease prognostic factors. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;15(Suppl 1):41–2. doi: 10.3109/10428199509052704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carde P. Should poor risk patients with Hodgkin's disease be sorted out for intensive treatments? Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;15(Suppl 1):31–40. doi: 10.3109/10428199509052703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandi L, Kumar L, Kochupillai V, Dawar R, Singh R. Hodgkin's disease: A retrospective analysis of 15 years experience at a large referral centre. Natl Med J Ind. 1998;11:212–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. International Harmonization Project on Lymphoma. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laskar S, Gupta T, Vimal S, Muckaden MA, Saikia TK, Pai SK, et al. Consolidation radiation after complete remission in hodgkin's disease following six cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine chemotherapy: Is there a need? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:62–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vashisht S, Aikat BK. Hodgkin's disease (retrospective study of 119 cases) Indian J Cancer. 1973;10:263–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinshaw KA, Advani SH, Gopal R, Nair CN, Talvalkar GV, Gangadharan P, et al. Management of Hodgkin's disease in western India. Cancer. 1984;54:1276–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841001)54:7<1276::aid-cncr2820540708>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rana R, Chopra R, Masih K, Zachariah A, Prabhakar BR, Mahajan MK. Hodgkin's disease: A clinicopathologic study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1995;8:245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Database: Incidence - SEER 17 1969-2006 Counties, National Cancer Institute April 2009, based on the November 2008 submission [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ultmann JE, Moran EM. Clinical course and complications of Hodgkin's disease. Arch Intern Med. 1973;131:332–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diehl V, Franklin J, Pfreundschuh M, Lathan B, Paulus U, Hasenclever D, et al. German Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group. Standard and increased dose BEACOPP chemotherapy compared with COPP-ABVD in advanced Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2386–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patkar N, Mehta J, Kulkarni B, Pande R, Advani S, Borges A. Immunoprofile of Hodgkin's lymphoma in India. Indian J Cancer. 2008;45:59–63. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.41772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duggan DB, Petroni GR, Johnson JL, Glick JH, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. Randomized comparison of ABVD and MOPP/ABV hybrid for the treatment of advanced Hodgkin's disease: Report of an intergroup trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:607–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobbi PG, Levis A, Chisesi T, Broglia C, Vitolo U, Stelitano C, et al. Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. ABVD versus modified stanford V versus MOPPEBVCAD with optional and limited radiotherapy in intermediate- and advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: Final results of a multi-center randomized trial by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9198–207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson PW, Radford JA, Cullen MH, Sydes MR, Walewski J, Jack AS, et al. United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY09 Trial (ISRCTN97144519) Comparison of ABVD and alternating or hybrid multidrug regimens for the treatment of advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma: Results of the United Kingdom lymphoma group LY09 trial (ISRCTN97144519) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9208–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoskin PJ, Lowry L, Horwich A, Jack A, Mead B, Hancock BW, et al. Randomized comparison of the stanford V regimen and ABVD in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin's Lymphoma: United Kingdom national cancer research institute lymphoma group study ISRCTN 64141244. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5390–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canellos GP, Niedzwiecki D. Long-term follow-up of Hodgkin's disease trial. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1417–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205023461821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viviani S, Zinzani PL, Rambaldi A, Brusamolino E, Levis A, Bonfante V, et al. Michelangelo Foundation; Gruppo Italiano di Terapie Innovative nei Linfomi; Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin's lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:203–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]