Abstract

Background and Rationale:

Medical professionals’ attitude towards homosexuals affects health care offered to such patients with a different sexual orientation. There is absence of literature that explores the attitudes of Indian medical students or physicians towards homosexuality.

Aim:

This study aimed to evaluate Indian medical students and interns’ knowledge about homosexuality and attitude towards homosexuals.

Materials and Methods:

After IEC approval and written informed consent, a cross-sectional study was conducted on a purposive sample of undergraduate medical students and interns studying in one Indian medical college. The response rate was 80.5%. Only completely and validly filled responses (N = 244) were analyzed. The participants filled the Sex Education and Knowledge about Homosexuality Questionnaire (SEKHQ) and the Attitudes towards Homosexuals Questionnaire (AHQ). SEKHQ consisted of 32 statements with response chosen from ‘true’, ‘false’, or ‘don’t know’. AHQ consisted of 20 statements scorable on a 5-point Likert scale. Multiple linear regression was used to find the predictors of knowledge and attitude.

Results:

Medical students and interns had inadequate knowledge about homosexuality, although they endorsed a neutral stance insofar as their attitude towards homosexuals is concerned. Females had more positive attitudes towards homosexuals. Knowledge emerged as the most significant predictor of attitude; those having higher knowledge had more positive attitudes.

Conclusion:

Enhancing knowledge of medical students by incorporation of homosexuality related health issues in the curriculum could help reduce prejudice towards the sexual minority and thus impact their future clinical practice.

KEY WORDS: Attitude, homosexuality, India, knowledge, medical students

Introduction

Given the relatively conservative cultural climate in India, those belonging to any sexual minority are subject to prejudices. Homophobia tends to be perpetuated by spiritual gurus and community leaders.[1] In 2009, the Delhi High Court revoked Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalized consensual acts of same-sex adults in private, and held that it violated the fundamental right of life and liberty and the right to equality as guaranteed in the Constitution.[2] However, this verdict was overturned by the Supreme Court of India in December 2013. An anti-homosexual stance can trickle down into the attitudes of doctors, which could translate into an unconscious bias in treatment encounters with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) patients despite an adequate medical education. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has already recognized that it is not a disorder. Considerable evidence has shown that the LGBT population has unique physical and mental health care needs. Yet, they tend to avoid routine health care for the fear of stigmatization by the medical community.[3]

Medical curricula in Canada and the United States were found to devote little time to impart formal training about LGBT related topics to in-the-making clinicians.[4,5] Physicians across specialties agree that they lack the required skills to address issues related to their patients’ sexual orientation.[6] The problem may be further compounded by physician homophobia, which impacts the doctor-patient relationship adversely and diminishes a patient's ability to disclose sensitive issues.[7] Although there has been a substantial reduction in physician homophobia over the last 30 years in the developed world, it is still not completely done away with.[8,9] A survey in Austria revealed that medical students had more negative attitude towards homosexuals than non-medical students.[10] Studies from Australia, China and Serbia have also found medical students tend to be prejudiced against the now increasingly visible sexual minority.[11,12,13] It may be argued that homophobia is difficult to gauge because, as with discrimination, underreporting often occurs,[14] yet the effort to find it out in medical professionals may prove to be worthwhile as it has implications in patient care and hence the present study assesses knowledge and attitudes among medical students and interns in an Indian medical college.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and written informed consent was taken from all participants.

Design and sampling and sample size

A cross sectional survey design with a convenience sampling. All undergraduate medical students and interns studying and working respectively in the institute to which the authors are affiliated were considered for inclusion in the study.

Study procedure

The first year (second semester), second year (fourth semester) and third year (sixth semester) medical students were approached en masse during a lecture session after permission from the respective heads of department of Anatomy, Pharmacology and Preventive and Social Medicine. The students were told that they would receive briefing about a new study, but the nature of the study was not told to them. Interns were approached on a one to one basis by one of the authors. Students and interns were then briefed about the types of sexual orientation, the unique health needs that minorities have, and how these need to be addressed in clinical practice. The rationale of the survey was then explained. Anonymity was ensured by asking those who consented not to reveal their identity on the filled questionnaire. At least three of the authors were present for the entire duration of the survery, the students filled the forms at a distance from each other and discussion between students was not permitted. The filled forms were dropped by both the students and the interns in a sealed drop box.

Survey instruments

Baseline demographics

Age, gender, religion, marital status, sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual), and year of medical schooling (first, second or third year medical student or intern).

The Sex Education and Knowledge about Homosexuality Questionnaire (SEKHQ)

Participants were required to express their opinion on the validity of 32 statements as “true”, “false”, or “don’t know”. The score on this scale ranged from 0-32, where 32 represented the score with all correct answers. Wrong answers or answers with the response “don’t know” were scored 0. The instrument was found to have a Cronbach's alpha of 0.724 in this study, but it was not validated prior to use. The questionnaire has been used previously by Dunjić-Kostić et al.[13] and was created by compilation of statements used in three previous studies.[15,16,17]

The Attitudes towards Homosexuals Questionnaire (AHQ)

It contains 20 statements regarding homosexuals, their lifestyle, and their social position and is scored by the participants on a 5-grade Likert type scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly agree⤝) to 5 (⤜Strongly disagree⤝). Some items require an inverse scoring. The score range on this scale was 20-100, with a higher score indicating a more negative attitude towards homosexuals. This instrument is also a compilation of items used in three previous studies,[8,18,19] and was used by Dunjić-Kostić et al. for their work.[13] The instrument was found to have a Cronbach's alpha of 0.810 in this study, but it was not validated prior to use.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data, frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean values with standard deviations for continuous variables. The normality of distribution was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. Independent samples t test and one way ANOVA were used to compare the knowledge and attitude questionnaire scores across different variables. Pearson's correlation was employed to find the correlation between age, knowledge and attitude questionnaire scores. Predictors of knowledge and attitude towards homosexuality were analyzed using multiple linear regression. Since only one participant identified himself/herself as homosexual and since only three participants reported being married, the variables sexual orientation and marital status were not analyzed separately. SPSS 17.0 was used for data analysis. Significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

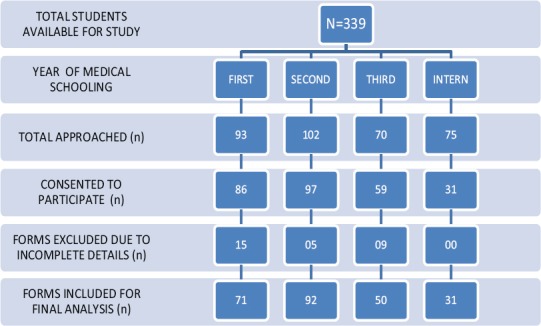

A total of 339 medical students and interns in all were approached and invited to participate, out of which 273 (80.5%) consented to participate and returned the filled questionnaires. Due to missing/invalid data, 29 (10.6%) forms were excluded so that the final sample for analysis consisted of 244 filled questionnaires [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of sample across different professional years

Table 1 displays the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. The sample had a male preponderance and a majority of the participants were Hindus. The mean age of the respondents was 20.04 (SD = 1.62) years, range 17-25. All the participants except one identified themselves as heterosexuals. The least participation in the study was from interns, who accounted for only 12.7% of the study population.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study sample (N = 244)

| Variable | Mean (S.D.)/n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 20.04 (1.62) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 137 (56.1) |

| Female | 107 (43.8) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 218 (89.3) |

| Others* | 26 (10.7) |

| Designation | |

| 1st year U.G.† | 71 (29.0) |

| 2nd year U.G.† | 92 (37.7) |

| 3rd year U.G.† | 50 (20.5) |

| Interns | 31 (12.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 243 (99.6) |

| Homosexual | 1 (0.4) |

| Bisexual | 0 |

| Marital Status | |

| Unmarried | 241 (98.7) |

| Married | 3 (1.3) |

*Others included Muslims, Jains, Christians, †Undergraduate students

Table 2 shows the association of gender, designation and religion with knowledge and attitude towards homosexuality. Females were found to have a more positive attitude towards homosexuals vis-à-vis males, although their knowledge about homosexuality did not differ significantly from males. Interns and third year medical students scored better than first and second year students on knowledge (P = 0.046), but the difference did not reflect in their attitude towards homosexuals. Although when all the respondents were considered as a single group, those with higher knowledge had more favorable attitudes [Table 3]. Likewise, non-Hindus had greater knowledge about homosexuality as against Hindus, but the difference in their attitude was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Association of gender, designation and religion with knowledge and attitude towards homosexuality (N = 244)

| Variable | Score on SEKHQ* | Score on AHQ† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (S.D.) | Significance t/F P value | Mean (S.D.) | Significance t/F P value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 10.8 (4.1) | t=0.853 | 57.7 (7.7) | t=2.463 |

| Female | 10.3 (4.3) | P=0.394 | 55.5 (9.5) | P=0.014 |

| Designation | ||||

| 1st year U.G.‡ | 10.3 (4.0) | F=2.714 | 57.2 (7.0) | F=1.240 |

| 2nd year U.G.‡ | 9.9 (4.1) | P=0.046 | 56.5 (8.9) | P=0.334 |

| 3rd year U.G.‡ | 11.5 (4.1) | 57.1 (8.0) | ||

| Interns | 11.7 (4.2) | 54.0 (5.7) | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 10.3 (4.1) | t= −3.010 | 56.8 (8.0) | t=1.680 |

| Others | 12.9 (4.2) | P=0.003 | 53.8 (12.6) | P=0.094 |

*Sex education and knowledge about homosexuality questionnaire, †Attitudes towards homosexuals questionnaire, ‡Undergraduate students

Table 3.

Correlation between age, knowledge and attitude towards homosexuality (N = 244)

| Variable | Score on SEKHQ* | Score on AHQ† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient (r) | Age | 0.16‡ | –0.08 |

| Score on SEKHQ* | –0.38‡ |

*Sex Education and Knowledge about Homosexuality Questionnaire †Attitudes towards Homosexuals Questionnaire ‡P<0.01

The score on SEKHQ [Table 3] correlated positively with age (being older entailed greater knowledge), and inversely with score on AHQ (those having higher knowledge had more positive attitudes). On stepwise multiple regression [Table 4], knowledge about homosexuality and gender could significantly predict attitude towards homosexuals explaining 14.3% and 2.8% of the variance respectively, while all the variables taken together accounted for 16.3% of the variance. Apart from attitude, religion emerged as a significant predictor of knowledge about homosexuality explaining 3.2% of the variance. The regression models for both knowledge and attitude were significant (P<0.001).

Table 4.

Predictors of knowledge and attitude towards homosexuality on linear regression (N = 244)

| Dependant variable | Predictor variable | T | P | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score on SEKHQ* | (Constant) | 2.15 | 0.03 | Adjusted |

| Age | 1.41 | 0.15 | R2=0.180 | |

| Gender | –1.81 | 0.07 | F=11.692 | |

| Religion | 2.40 | 0.01 | P=0.000 | |

| Designation | –0.33 | 0.74 | ||

| Attitude | –6.29 | 0.000 | ||

| Score on AHQ† | (Constant) | 6.59 | 0.000 | |

| Age | –0.07 | 0.941 | ||

| Gender | –3.02 | 0.003 | ||

| Religion | –0.66 | 0.51 | Adjusted | |

| Designation | –0.11 | 0.91 | R2=0.163 | |

| Knowledge | –6.29 | 0.000 | F=10.464 | |

| P=0.000 |

*Sex education and knowledge about homosexuality questionnaire, †Attitudes towards homosexuals questionnaire

Table 5 shows the percentage of correct responses on each item of the SEKHQ. On 28 of the 32 questions about knowledge related to homosexuality, less than half of the participants responded correctly. Less than 10 percent of the participants could correctly respond that there has not been an increase in homosexuality in the last 25 years. The highest correct response of about 72.5 percent was for the statement that homosexuals usually disclose their sexual identity to a friend before they tell a parent. The mean total score of the respondents on the SEKHQ was 10.59 (SD 4.19), range 1-21.

Table 5.

Response on sex education and knowledge about homosexuality questionnaire

| (Correct response) statement | Correct response (N = 244) n (%) |

|---|---|

| (F) Approximately 25-30% of adolescent boys have a homosexual experience during their teenage years | 82 (33.6) |

| (F) A majority of homosexuals were seduced in adolescence by a person of the same sex, usually several years older | 59 (24.1) |

| (T) Approximately 6-11% of adolescent girls have a homosexual experience during their teenage year | 91 (37.2) |

| (T) Sexual orientation is usually well-established by adolescence | 171 (70.1) |

| (T) The homosexuals usually disclose their sexual identity to a friend before they tell a parent | 177 (72.5) |

| (F) A homosexual person’s gender identity does not agree with his/her biological sex | 65 (26.6) |

| (F) If children are raised by openly homosexual parents, the likelihood that they themselves will develop a homosexual orientation is greater than if they were raised by heterosexual parents | 88 (36.1) |

| (T) Gay men and lesbian women have an increased incidence of anxiety and depression compared to heterosexual men and women | 132 (54.1) |

| (F) Homosexuals place more importance on the physical attractiveness of their dating partners than do heterosexuals | 63 (25.8) |

| (T) The experience of love is similar for all people regardless of sexual orientation | 123 (50.4) |

| (T) Gay male couples are likely to have the most permissive attitudes about sexual activity outside of a committed relationship compared to lesbian couples and heterosexual couples | 49 (20.1) |

| (T) In some cultures, it is normal practice for boys to have sex with their same-gender during adolescence. | 53 (21.7) |

| (F) In the world as a whole, the most common mode of transmission of the HIV virus is through gay male sex | 102 (41.8) |

| (T) Testosterone is the hormone responsible for the growth of pubic hair on girls | 57 (23.3) |

| (T) Boys’ breasts typically grow during puberty | 60 (24.5) |

| (F) Research supports the notion that sex education offered in schools increases the amount of sexual activity amongst adolescents | 87 (35.6) |

| (F) In the last 25 years there has been an increase in homosexuality | 23 (9.4) |

| (F) Most homosexual men and women want to be heterosexual | 98 (40.2) |

| (F) Most homosexuals want to encourage or entice others into a homosexual or gay lifestyle | 84 (34.4) |

| (T) Heterosexual teachers, more often than homosexual teachers, seduce their students or sexually exploit them | 90 (36.8) |

| (F) Greece and Rome fell because of homosexuality | 53 (21.7) |

| (F) Heterosexuals generally have a stronger sex drive than do homosexuals | 49 (20.1) |

| (T) About one-half of the population of men and more than one-third of women have had a homosexual experience to the point of orgasm at some time in their lives | 40 (16.3) |

| (T) The homosexual population includes a greater proportion of men than of women | 123 (50.4) |

| (T) Heterosexual men and women commonly report homosexual fantasies. | 50 (20.4) |

| (F) If the media portrays homosexuality or lesbianism as positive, this could sway youths into becoming homosexual or desiring homosexuality as a way of life | 82 (33.6) |

| (F) Homosexuals are usually identifiable by their appearance or mannerisms | 64 (26.2) |

| (F) Homosexuals do not make good role models for children and could do psychological harm to children with whom they interact as well as interfere with the normal sexual development of children | 103 (42.2) |

| (T) Gay men are more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general public | 77 (31.5) |

| (F) Homosexuality does not occur among animals (other than human beings) | 63 (25.8) |

| (F) Historically, almost every culture has evidenced widespread intolerance towards homosexuals, viewing them as “sick” or as “sinners” | 23 (9.4) |

| (T) Heterosexual men tend to express more hostile attitudes towards homosexuals than do heterosexual women | 103 (42.2) |

Table 6 presents the mean scores obtained on each item of the AHQ. Negative attitudes towards homosexuals were most reflected on statements like “If gay men want to be treated like everyone else, then they need to stop making such a fuss about their sexuality/culture”, “In today's tough economic times, tax money shouldn’t be used to support gay men's organizations”, “Gay men have become far too confrontational in their demand for equal rights”, and “I would not be too upset if I learned that my son was homosexual.” The mean total score of the respondents on the AHQ was 56.52 (SD 8.63), range 25-85.

Table 6.

Response on attitudes towards homosexuals questionnaire

| Statement | Response Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Homosexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should not be condemned | 2.48±0.90 |

| Gay men do not have all the rights they need | 2.86±1.01 |

| Celebrations such as “Gay Pride Day” are ridiculous because they assume that an individual’s sexual orientation should constitute a source of pride | 3.07±0.97 |

| Gay men still need to protest for equal rights | 2.61±0.85 |

| If gay men want to be treated like everyone else, then they need to stop making such a fuss about their sexuality/culture | 3.49±0.86 |

| Gay men who are “out of the closet” should be admired for their courage | 2.87±0.99 |

| In today’s tough economic times, tax money shouldn’t be used to support gay men’s organizations | 3.28±0.90 |

| Gay men have become far too confrontational in their demand for equal rights | 3.18±0.85 |

| It would be beneficial to society to recognize homosexuality as normal | 2.63±1.00 |

| Homosexuals should not be allowed to work with children | 2.62±1.04 |

| The homosexuals should have equal opportunity of employment | 2.15±0.87 |

| Homosexuals should be allowed to marry | 2.5±0.97 |

| Homosexuals should be given social equality | 2.36±0.94 |

| I think male homosexuals are disgusting | 2.72±0.99 |

| If a man has homosexual feelings, he should do everything he can do to overcome them | 2.94±1.02 |

| I would not be too upset if I learned that my son was homosexual | 3.16±0.97 |

| Homosexual couples should be allowed to adopt children just like heterosexual couples | 2.52±0.96 |

| Homosexuals are sick | 2.57±0.99 |

| Just as in other species, male homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in human man | 2.48±0.90 |

| Many gay men use their sexual orientation so that they can obtain special privileges | 3.13±0.74 |

Discussion

There is dearth of Indian literature that has systematically investigated issues related to homosexuality,[1] and this is the first such effort to study the knowledge and attitude of medical students towards the same in an Indian set up. The findings suggest that overall the participants lacked adequate knowledge about homosexuality, although they endorsed a more or less neutral stance insofar as their attitude towards homosexuality is concerned. Western medical school curricula inadequately address and give very less time to the health and sexuality issues of LGBT people.[4,5] In absence of any publications or formal reports, it is not exactly known how much importance medical curriculum gives to homosexuality and related health issues in India, although it may be apprehended that it may not be getting its due, which is reflected in the low knowledge level of students in this study. In fact, Indian medical textbooks give misleading information on the subject,[20] promoting a sense of bias against homosexuals. Knowledge about homosexuality emerging as the strongest predictor of a positive attitude towards homosexuals in this study only reiterates the previously proposed notion that enhancing knowledge maybe a possible tool to reduce the prejudice meted out to and stigmatization faced by the sexual minorities, especially during their encounters with medical professionals.[13]

To increase the knowledge and awareness of doctors about issues related to homosexuality, it becomes imperative to incorporate education about alternate sexuality in the medical teaching programs, not to champion the cause of homosexuality but to expose students to alternative views of sexuality, challenge their values and beliefs, and celebrate diversity.[21] This in turn could enhance their professionalism and help them offer better health care to their LGBT patients with a minimal sense of discrimination creeping in, as health care providers who have negative attitudes toward same-sex behavior have been found to provide inadequate care for LGBT individuals.[22] Lack of disclosure of sexual orientation to physicians significantly decreases the likelihood that appropriate health services are recommended to such patients.[23] On the brighter side, previous research shows that practicing physicians and medical students alike have expressed the need to include such training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.[3,24] Greater clinical exposure to LGBT patients at the undergraduate level enhances knowledge of LGBT health care concerns and brings about a more positive attitude,[25] further emphasizing the need.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has recommended that “medical school curricula ensure that students master the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to provide excellent, comprehensive care for LGBT patients” by including “comprehensive content addressing the specific healthcare needs of LGBT patients” and “training in communication skills with patients and colleagues regarding issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.”[26] Laying of such guidelines or recommendations, though highly desired has eluded the Indian medical education scenario.

It cannot be exactly explained why religion affects knowledge but not attitudes in this work. The wide gap in the number of Hindu and non-Hindu participants could be a probable reason. Females medical students tend to have a more tolerant attitude towards homosexuals,[10,12,13] as also substantiated by this study. Although the regression models for both knowledge and attitude were highly significant (P < 0.001), the relatively limited variance explained by the independent variables included in the models suggests the need to examine other factors that may influence medical students’ knowledge about homosexuality and attitudes towards homosexuals. Factors that may affect and shape attitudes could be cultural orientation and personal religious beliefs (and not just religious affiliation),[27] family environment[28] and effect of media[29] amongst others.

Limitations

Firstly, the response rate in this study was 80.5%. Response rates have ranged from 13%[8] to 88.5%[13] in previous such surveys. India, being a culturally and sexually conservative country, where respondents may feel less comfortable in expressing their views on sexuality related issues; such a response rate is still deemed to be decent. It may be apprehended that those who denied to participate had more negative attitudes towards homosexuals. Secondly, the questionnaires used in this study were not assessed for their psychometric properties other than internal consistency reliability which was found to be satisfactory. Thirdly, conducting this survey in a classroom may have introduced a bias - in such a setting, one may not get truthful answers about people's own sexual orientation, and more importantly, there may be an over representation of neutral opinions about homosexuality. Also, the fact that only 41.3% interns opted to participate when approached one to one may indicate that most other students would have done the same, had it not been for the en masse approach used. That the participants were told as a part of introduction to the study that LGBT patients may have special needs and that as doctors they would be expected to help out may be another potential source of bias causing over reporting of positive views. Lastly, the results of this work reflect the attitudes of medical students of a single medical teaching institute of India, and so cannot be extrapolated to the larger population of medical students of India.

Conclusion and Implications

This study gives preliminary insight into the knowledge and attitude of Indian medical students about homosexuality, although further research on a larger scale is needed across the country to have a more comprehensive impression about the stand of medical students on the issue, which could help to draft guidelines on inclusion of homosexual patients’ health needs in the Indian medical curriculum. It has been rightly commented that medical treatment has more to do with doctors’ values and attitudes than with objective realities.[30] Both patients and doctors differ in their beliefs, attitudes, and hopes. The art of medicine depends on the ability to acknowledge and respect these differences and treat every patient as an individual.[31] Medical students need to be trained to maintain a non-homophobic attitude and to be aware about how their own attitude affects clinical judgment.[32] Enhancing knowledge of medical students by adequate incorporation of LGBT issues in the curriculum could help reduce practicing doctors’ prejudice faced by LGBT patients and improve the health care offered to such patients.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Maja Ivković, Assistant Professor (Psychiatry), Medical School of Belgrade University & Clinic for Psychiatry, Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade for allowing us the use of the questionnaires and reviewing the manuscript. We also extend our gratitude to Dr. Jitendra Patel, Dr. V.J. Patel and Dr. D.V. Bala, Heads of the Departments of Anatomy, Pharmacology and Community Medicine, Smt. N.H.L. Municipal Medical College, Ahmedabad, India respectively for allowing the conduct of the study during lecture sessions of the respective subjects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rao TS, Jacob KS. Homosexuality and India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:1–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.94636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar N. Delhi High Court strikes down Section 377 of IPC. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 11]. Available from: http://www.hindu.com/2009/07/03/stories/2009070358010100.htm .

- 3.Harrison AE. Primary care of lesbian and gay patients: Educating ourselves and our students. Fam Med. 1996;28:10–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, White W, Tran E, Brenman S, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306:971–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallick MM, Cambre KM. Townsend MH. How the topic of homosexuality is taught at U.S medical schools. Acad Med. 1992;67:601–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitts RL. Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex. 2010;57:730–47. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2010.485872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klamen DL, Grossman LS, Kopacz DR. Medical student homophobia. J Homosex. 1999;37:53–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DM, Mathews WC. Physicians’ attitudes toward homosexuality and HIV: Survey of a California Medical Society- revisited (PATHH-II) J Homosex. 2007;52:1–9. doi: 10.1300/J082v52n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matharu K, Kravitz RL, McMahon GT, Wilson MD, Fitzgerald FT. Medical students’ attitudes towards gay men. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold O, Voracek M, Musalek M, Springer-Kremser M. Austrian medical students’ attitudes towards male and female homosexuality: A comparative survey. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:730–6. doi: 10.1007/s00508-004-0261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman R, Watkins R, Zappia T, Nicol P, Shields L. Nursing and medical students’ attitude, knowledge and beliefs regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender parents seeking health care for their children. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:938–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hon KL, Leung TF, Yau AP, Wu SM, Wan M, Chan HY, et al. A survey of attitudes toward homosexuality in Hong Kong Chinese medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:344–8. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1704_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunjić-Kostić B, Pantović M, Vuković V, Randjelović D, Totić-Poznanović S, Damjanović A, et al. Knowledge: A possible tool in shaping medical professionals’ attitudes towards homosexuality. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24:143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gschwind H. Homosexual men in doctors’ practices: Results of an empirical study of the relationship between doctor and patient. Zeitschrift Fuer Sexualforschung. 1992;5:314–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris MB, Nightengale J, Owen N. Health care professionals’ experience, knowledge, and attitudes concerning homosexuality. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1995;2:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alderson KG, Orzeck TL, McEwen SC. Alberta high school counselors’ knowledge of homosexuality and their attitudes toward gay males. CJE. 2009;32:87–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells JW, Franken ML. University students’ knowledge about and attitudes toward homosexuality. J Humanist Educ Dev. 1987;26:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison MA, Morrison TG. Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. J Homosex. 2002;43:15–37. doi: 10.1300/j082v43n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herek G. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbian and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. J Sex Res. 1988;25:451–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S, Ghosh S. Void in the sphere of wisdom: A distorted picture of homosexuality in medical textbooks. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10:138–9. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2013.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brondani MA, Paterson R. Teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues in dental education: A multipurpose method. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1354–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliason MJ, Schope R. Does “Don’t ask, don’t tell” apply to health care. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people's disclosure to health care providers? J Gay Lesb Med Assoc. 2001;5:125–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petroll AE, Mosack KE. Physician awareness of sexual orientation and preventive health recommendations to men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:63–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ebd50f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinchliff S, Gott M, Galena E. ’I daresay I might find it embarassing’: General practitioners’ perspectives on discussing sexual health issues with lesbian and gay patients. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13:345–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A. Medical students’ ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med. 2006;38:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2007. Joint AAMC-GSA and AAMC-OSR Recommendations Regarding Institutional Programs and Educational Activities to Address the Needs of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (GLBT) Students and Patients; pp. 74–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamczyk A, Pitt C. Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: The role of religion and cultural context. Soc Sci Res. 2009;38:338–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kissinger DB, Lee SM, Twitty L, Kisner H. Impact of family environment on future mental health professionals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. J Homosex. 2009;56:894–920. doi: 10.1080/00918360903187853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee TT, Hicks GR. An analysis of factors affecting attitudes toward same-sex marriage: Do the media matter? J Homosex. 2011;58:1391–408. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.614906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner BS. Medical power and social knowledge. London: Sage; 1987. p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerjee A, Sanyal D. Dynamics of doctor-patient relationship: A cross-sectional study on concordance, trust, and patient enablement. J Family Community Med. 2012;19:12–9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.94006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahan R, Feldman R, Hermoni D. The importance of sexual orientation in the medical consultation. Harefuah. 2007;146:626–30. 644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]