Abstract

Plants of the Amaryllidaceae family produce a large variety of alkaloids and non-basic secondary metabolites, many of which are investigated for their promising anticancer activities. Of these, crinine-type alkaloids based on the 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine ring system were recently shown to be effective at inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells resistant to various pro-apoptotic stimuli and representing tumors with dismal prognoses refractory to current chemotherapy, such as glioma, melanoma, non-small-cell lung, esophageal, head and neck cancers, among others. Using this discovery as a starting point and taking advantage of a concise biomimetic route to the crinine skeleton, a collection of crinine analogues were synthetically prepared and evaluated against cancer cells. The compounds exhibited single-digit micromolar activities and retained this activity in a variety of drug-resistant cancer cell cultures. This investigation resulted in the discovery of new bicyclic ring systems with significant potential in the development of effective clinical cancer drugs capable of overcoming cancer chemotherapy resistance.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Apoptosis resistance, Multidrug resistance, Translation inhibition, Lycorine, Haemanthamine

1. Introduction

Apoptosis resistance is a hallmark of cancer, because defects in apoptosis regulators invariably accompany tumorigenesis and sustain malignant progression. Because most standard chemotherapeutic agents work by inducing apoptosis in cancer cells [1,2], its disruption during tumor evolution can promote intrinsic drug resistance and result in therapy failure. For example, one type of cancer with such intrinsic resistance to apoptosis induction is glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). GBM cells are generally highly resistant to many different apoptotic stimuli resulting in low effectiveness of classical pro-apoptotic therapeutic approaches [3,4]. Indeed, GBM is characterized by a deregulated tumor genome containing opportunistic deletions of tumor suppressor genes as well as amplification or mutational hyper-activation of receptor tyrosine kinase receptors [5]. These genetic changes result in enhanced survival pathways and systematic defects in the apoptotic machinery [5]. As a result, GBM is associated with dismal prognoses [4–8] and GBM patients have a median survival expectancy of less than 14 months when treated with a standard protocol of surgical resection, radiotherapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide (TMZ) [9,10]. Other apoptosis-resistant cancers include the tumors of the lung, liver, stomach, esophagus, pancreas as well as melanomas, and they are all associated with dismal prognoses [11].

In addition to intrinsic resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, tumors often develop acquired resistance, in which they are initially susceptible to treatment and patients respond to chemotherapy but then become refractory to a broad spectrum of structurally and mechanistically diverse antitumor agents. This phenomenon, referred to as multidrug resistance (MDR) [12,13], usually results from upregulation of protein pumps, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp), leading to the reduction of drug concentration in cancer cells. MDR is one of the major causes of chemotherapy failure, for example with such widely used anticancer drugs as the vinca alkaloids [14] or the taxanes [15].

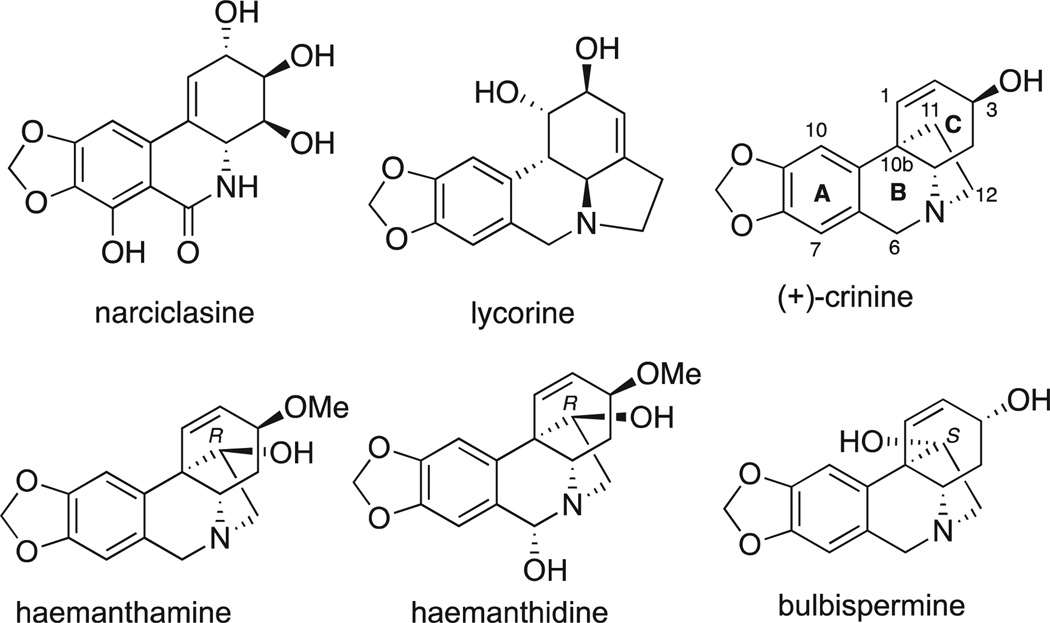

In search of medicinal leads capable of combating drug-resistant cancers, we have been investigating small molecule constituents of the Amaryllidaceae plants, whose medicinal value has been recognized for a long time. The use of Amaryllidaceae plants dates back to at least the fourth century BC, when Hippocrates of Cos used oil from the daffodil Narciclasus poeticus L. for the treatment of cancer [16]. In more recent times, a large number of structurally diverse alkaloids, along with non-basic amidic constituents (isocarbostyrils), possessing a wide spectrum of biological activities have been isolated from the Amaryllidaceae species [17–20]. A number of these natural products, such as phenanthridines narciclasine, lycorine and so-called crinine-type alkaloids containing a C11,C12 ethylene bridge on the phenanthridine skeleton, such as haemanthamine, haemanthidine and bulbispermine (Fig. 1), are of interest due to their promising anticancer properties [21]. Thus, narciclasine and lycorine have been actively investigated for their potent anti-tumor effects, both in vitro and in vivo, in various pre-clinical models of human cancers by many research groups [22–30], including their evaluation as cytostatic agents active against apoptosis-resistant cancers by us [31–37]. The anti-proliferative activity of the crinine-type alkaloids has also been reported by natural product chemists on numerous occasions [38–44]. However, despite some dated work reporting the inhibition of protein biosynthesis by crinine-type alkaloids [45], the paucity of in-depth biological studies [46–48] of the anticancer effects of these compounds has led to insufficient attention to these agents from the medicinal chemistry community. We recently showed, however, that these 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine alkaloids, including haemanthamine, haemanthidine and bulbispermine, appear to be as promising in the treatment of apoptosis-resistant cancers as their congeners, narciclasine and lycorine [32,48]. We demonstrated that at antiproliferative GI50 doses, these crinine-type alkaloids exhibit non-apoptotic cytostatic effects, while apoptosis induction (in apoptosis-sensitive cell lines) require 5–10 times higher doses [32]. Furthermore, using bulbispermine as a model crinine-type alkaloid, we demonstrated that these cytostatic effects occur through impairing the actin cytoskeleton organization [48].

Fig. 1.

Structures of selected Amaryllidaceae anticancer constituents.

This discovery makes the crinine-type alkaloids an excellent starting point for the generation of compounds able to combat cancers, which are naturally resistant to chemotherapy, such as glioblastoma, melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), among others. The investigation reported herein describes the generation of a collection of synthetic compounds based on the crinine-type 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine skeleton with the aim of obtaining new structural leads with activity against drug-resistant cancer cells.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

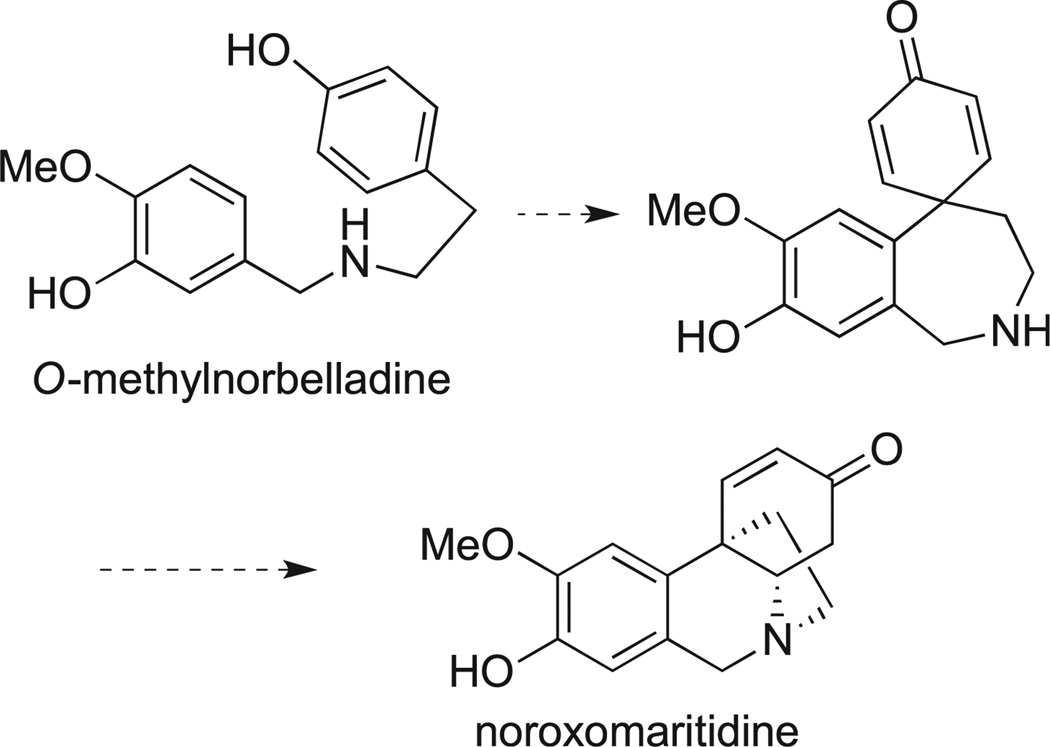

Our synthetic route is based on the use of a biomimetic synthesis of the crinine skeleton. The results of radiotracer experiments revealed that the biosynthesis of the crinine skeleton involves an intramolecular para-para oxidative coupling of O-methylnorbelladine with the subsequent intramolecular Michael cyclization to afford noroxomaritidine (Scheme 1) [21]. This oxidative phenolic coupling has been successfully performed in laboratory and the first biomimetic synthesis of the crinine skeleton was achieved using a vanadium oxytrichloride-promoted reaction reported in 1970 by Schwartz and Holton [49]. More recent modifications of this method involved the reactions utilizing hypervalent iodine to achieve the desired phenolic coupling. Such efforts led to the total syntheses of maritidine [49–51], siculine [52], oxocrinine [52], epicrinine [52], powelline [53], and 14,15-dideoxycripowellin [54]. Analysis of all published total syntheses of the crinine-type alkaloids reveals that the biomimetic strategy provides the shortest route to these natural products. However, prior to our investigation, it had not been applied to the generation of synthetic analogues with the crinine-like 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine ring system.

Scheme 1.

Biosynthesis of the crinine skeleton.

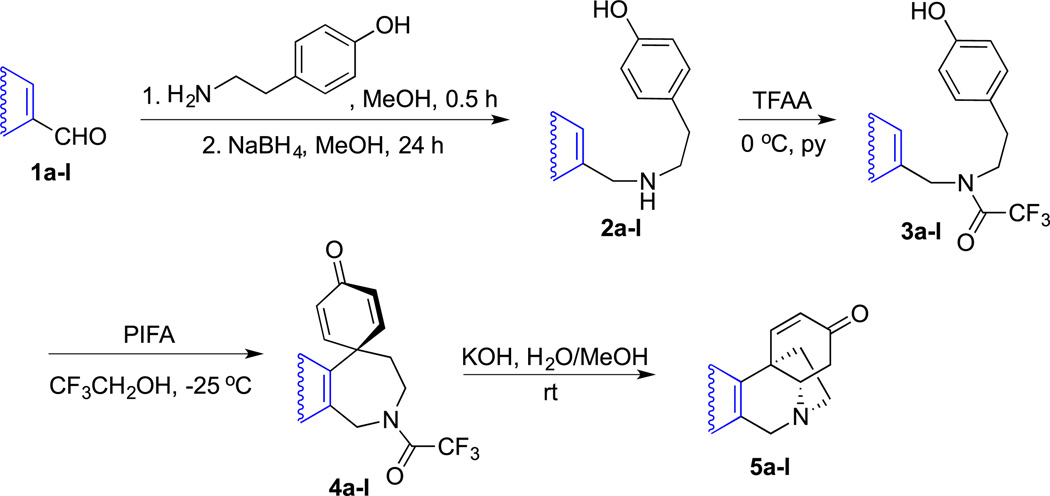

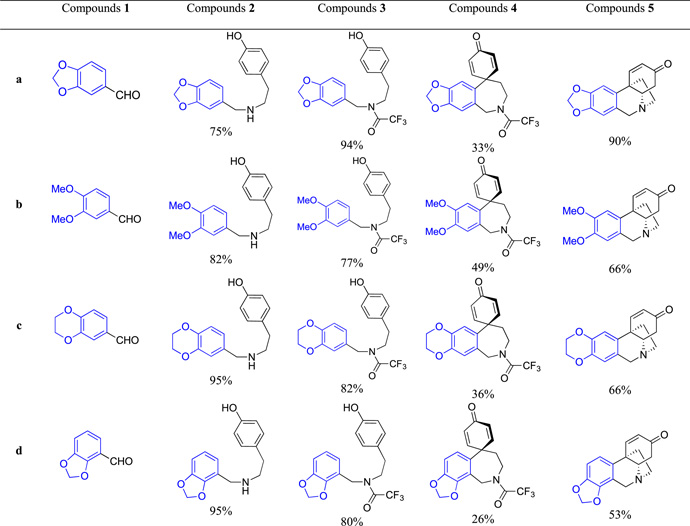

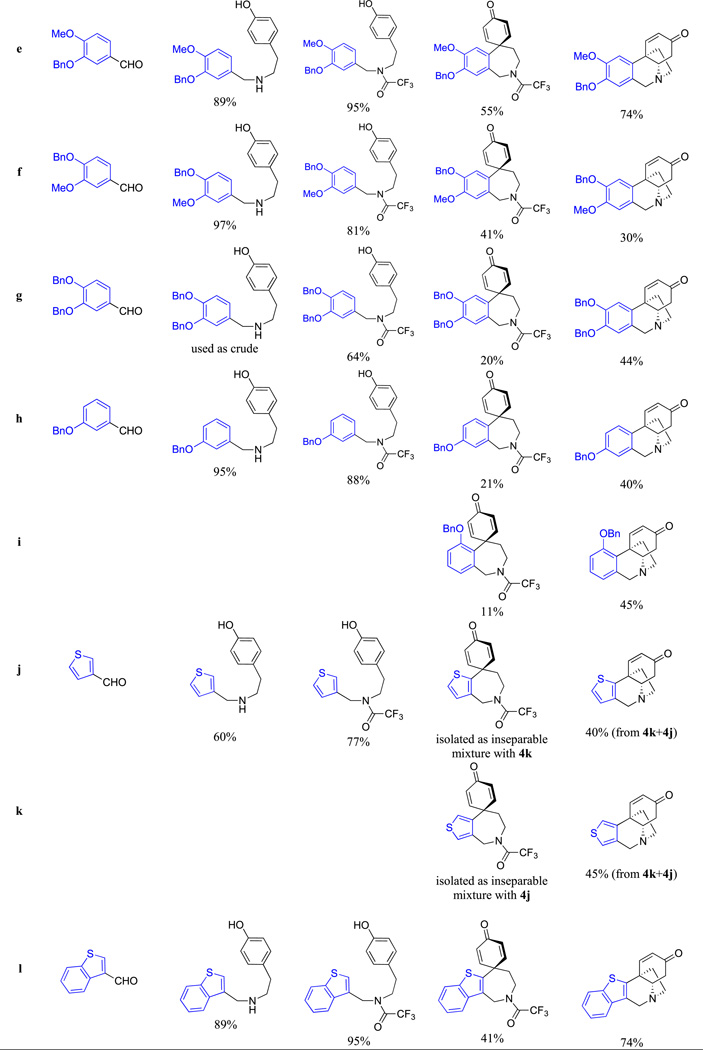

Thus, to utilize this biomimetic approach [52], various aromatic aldehydes 1a–l were reacted with tyramine to form imines, which without isolation were reduced with sodium borohydride to the corresponding amines 2a–l (Scheme 2). These were protected as trifluoroacetamides 3a–l and then converted to spirodienones 4a–l upon the oxidative cyclization promoted with phenyliodine (III) bis(trifluoroacetate) (PIFA) in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. Removal of the trifluoroacetamide protection led to an intramolecular Michael addition to generate the 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine ring system 5a–l. The structures of the synthesized compounds and reaction yields are given in Table 1. As can be seen, in all shown examples the key oxidative cyclization of 3 → 4 was highly regioselective with the exception of substrates 3h and 3j, where mixtures of isomeric spirodienones 4h/i and 4j/k were obtained. These subsequently gave pure regioisomeric crinine analogues 5h and 5i as well as 5j and 5k, respectively (Table 1).

Scheme 2.

General route toward synthetic analogues of the crinine-like alkaloids.

Table 1.

Compound structures and synthetic yields.

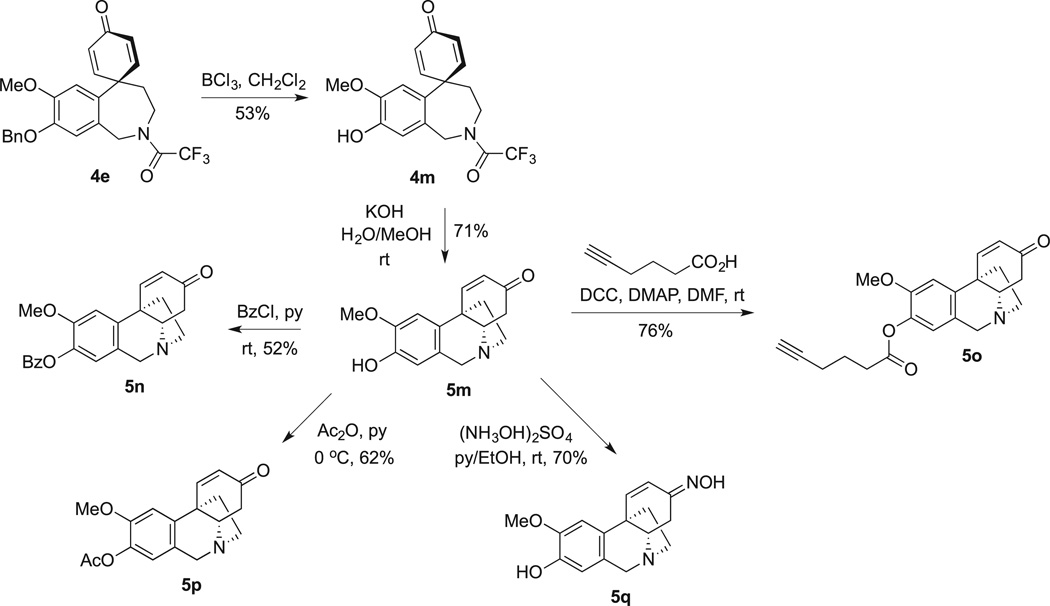

To obtain additional 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines inaccessible by the direct oxidative coupling approach, crinine alkaloid noroxomaritidine (5m), containing a free phenolic hydroxyl, was prepared utilizing a published procedure involving debenzylation of spirodienone 4e to phenol 4m followed by intramolecular cyclization upon treatment with potassium hydroxide (Scheme 3). This synthetically prepared alkaloid was derivatized at the phenolic hydroxyl to obtain esters 5n, 5o, 5p and converted to oxime 5q.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis and derivatization of noroxomaritidine (5m).

2.2. Pharmacology

2.2.1. Structure-activity relationship

Because spirodienones 4 have not to our knowledge been evaluated for anticancer activities before, these compounds, together with the desired 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5, were subjected to in vitro growth inhibition MTT assay [55] against two cell lines, human HeLa cervical and MCF-7 breast adenocarcinomas (Table 2). Depending on the type of the aromatic ring A, the anti-proliferative GI50 values for 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5a-5p, containing the C3-carbonyl moiety, ranged from single digit to >100 µM. High potency appeared to be associated with compounds containing large hydrophobic ether substituents in the ring A portion of the molecule (e.g., 5e-5i and 5l). The most noteworthy are compounds 5g and 5l, incorporating two benzyl substituents and a novel benzothiophene-based bicyclic ring system, respectively, possessing single digit micromolar GI50 values. In contrast, the compounds, whose ring A is substituted with large ester moieties (5n and 5o) were only weakly active, demonstrating the importance of maintaining the electron-rich character of ring A. Conversion of the C3-carbonyl to the oxime functionality also resulted in a loss of activity (see 5q). Most unexpectedly, spirodienones 4a-4m produced a range of activities that paralleled that of the 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5a-5m, to which they are converted upon hydrolytic removal of the trifluoroacetic protection. For example, this is clearly pronounced in the potent 4l/5l, inactive 4m/5m or moderately active 4a/5a pairs. This raises the question of whether compounds 4 undergo intracellular hydrolysis by non-specific amidases or even esterases [56] followed by an intramolecular cyclization to release the active compounds 5. The hydrolytic lability of the trifluoroacetamide group has been observed to be even higher than that of a methyl ester [57] and, although it appears there are no examples of this functionality in clinically approved drugs, ester-containing prodrugs that undergo hydrolysis to release the active drug are common [58].

Table 2.

Antiproliferative activities of spirodienones 4 and 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5.

| Compound | Cell viabilitya GI50, µM | Compound | Cell viabilitya GI50, µM | Compound | Cell viabilitya GI50, µM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | MCF-7 | HeLa | MCF-7 | HeLa | MCF-7 | |||

| 4a | 24 ± 2 | 30 ± 2 | 4f | 34 ± 4 | 34 ± 2 | 4k | NI | NI |

| 5a | 25 ± 3 | 24 ± 1 | 5f | 17 ± 2 | 17 ± 0 | 5k | 25 ± 5 | 44 ± 2 |

| 4b | 83 ± 5 | >100 | 4g | 17 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 4l | 10 ± 0 | 7 ± 1 |

| 5b | 64 ± 3 | >100 | 5g | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 0 | 5l | 8 ± 1 | 5 ± 0 |

| 4c | 21 ± 1 | 34 ± 12 | 4h | 16 ± 0 | 40 ± 1 | 4m | >100 | >100 |

| 5c | 13 ± 2 | 19 ± 1 | 5h | 8 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | 5m | >100 | >100 |

| 4d | >100 | >100 | 4i | 11 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 5n | 35 ± 1 | 45 ± 1 |

| 5d | 61 ± 5 | 73 ± 3 | 5i | 7 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 5o | 43 ± 2 | 53 ± 1 |

| 4e | 38 ± 2 | 48 ± 3 | 4j | NIb | NI | 5p | >100 | >100 |

| 5e | 12 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 5j | 8 ± 1 | 12 ± 0 | 5q | >100 | >100 |

Concentration required to reduce the viability of cells by 50% after a 48 h treatment with the indicated compounds relative to a DMSO control ± SD from two independent experiments, each performed in 4 replicates, as determined by the MTT assay.

NI = not isolated in pure form.

2.2.2. Activity against cells exhibiting intrinsic resistance to apoptosis, MDR phenotype, stem-like cell properties and other clinically relevant types of drug resistance

Based on our previous studies with the alkaloid bulbispermine [48], found to retain activity against apoptosis-resistant glioblastoma cells, the synthesized compounds were evaluated for in vitro growth inhibition against a panel of additional cancer cell lines containing U373 [59,60], U251 [61], U87 [61], T98G [59] human GBM and A549 NSCLC [62], all exhibiting various degrees and mechanisms of apoptosis resistance, as well as an apoptosissensitive tumor model, Hs683 anaplastic oligodendroglioma [59], used as reference. The obtained GI50 values associated with spirodienone 4l, 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5l and 5g and bulbispermine control are shown in Table 3. The data reveal that these compounds retain the single-digit micromolar antiproliferative GI50 values in this challenging cancer cell panel making them more potent than our previously studied lead, alkaloid bulbispermine, displaying double-digit micromolar potencies.

Table 3.

Antiproliferative activities of spirodienone 4l and crinine analogues 5g and 5l against cancer cells displaying various types of drug resistance.

| GI50

in vitro values (µM)a | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Glioma |

Lung cancer |

Uterine sarcoma |

|||||||||

| Hs683 | U373 | U251 | U87 | T98G | GBM 090909 | GBM 031810 | A549 | H1993 | H2073 | MES-SA | MES-SA/Dx5 | |

| 4l | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 7 | 8 | –b | 12 | 50 | 5 | 5 |

| 5l | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 7 |

| 5g | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | – | – | 4 | – | – | 2 | 7 |

| Bulbispermine | 27 | 53 | 41 | 38 | 99 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TMZ | – | – | – | – | – | 50 | >1000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Paclitaxel | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.004 | 2.4 | 0.007 | 10 |

Average concentration required to reduce the viability of cells by 50% after a 48–96 h treatment with the indicated compounds in varied numbers of replicates, as determined by the MTT assay.

– = not tested.

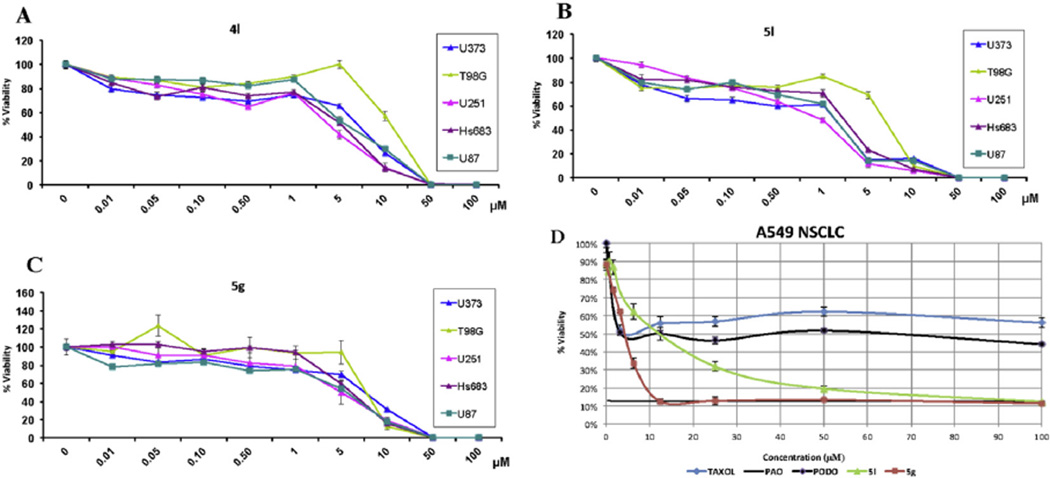

It is often observed that cells resistant to various pro-apoptotic stimuli contain a sensitive population that quickly responds to pro-apoptotic agents, but a significant portion of the cells in the culture resists the effects of the pro-apoptotic agents even at concentrations 100- or 1000-fold of their GI50 values [60]. Fig. 2A – C shows the absence of such resistant populations in five GBM cell lines treated with spirodienone 4l and 5,10b-ethanophenanthridines 5g and 5l. Indeed, as can be seen on the example of apoptosis-resistant A549 NSCLC cells (Fig. 2D), crinine analogues 5g and 5l are equally effective against most of the cells in the A549 NSCLC cultures and, with increasing concentration, rapidly reach antiproliferative levels of a non-discriminate cytotoxic agent phenyl arsine oxide (PAO). In contrast, common proapoptotic agents paclitaxel and podophyllotoxin have no effect on proliferation of ca. 50% of cells in these cultures at concentrations up to 100 µM.

Fig. 2.

Activity of spirodienone 4l and crinine analogues 5g and 5l against cell populations resistant to proapoptotic agents determined with the MTT assay. A–C: growth curves of five GBM cell cultures treated with 4l, 5l and 5g, respectively (one experiment performed in six replicates). D: growth curves of A549 NSCLC cell cultures treated with 5l, 5g, paclitaxel, phenyl arsine oxide (PAO) and podophyllotoxin (PODO, two independent experiments, each performed in 4 replicates).

It has been shown that glioma cells grown in neurosphere conditions exhibit stem-like properties through the ability of self-renewal and differentiation into multiple neural lineages. Furthermore, such cells recapitulate human gliomas on both histological and genetic levels more faithfully than serum cultured glioma cell lines when injected into the brains of mice [63–66] and are generally resistant to radiation and chemotherapy [67–70]. It is thus noteworthy that spirodienone 4l and 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine 5l retained similar levels of activity in neurosphere cultures 090909 and 031810 (Table 3). The former line, 090909, was derived from a patient who initially responded to TMZ, whereas the latter was derived from the same patient after progressing on temozolomide due to high O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) expression. MGMT is a protein capable of repairing mutagenic lesions produced by TMZ, therefore elevated MGMT expression confers resistance to TMZ even at concentrations as high as 1000 µM (Table 2). Importantly, methylation arrays show that almost 50% of patients with GBM have tumors that are unmethylated at the MGMT promoter site, leading to temozolomide resistance and poor outcome [71]. To date, no alternative treatment exists for this group of patients [71].

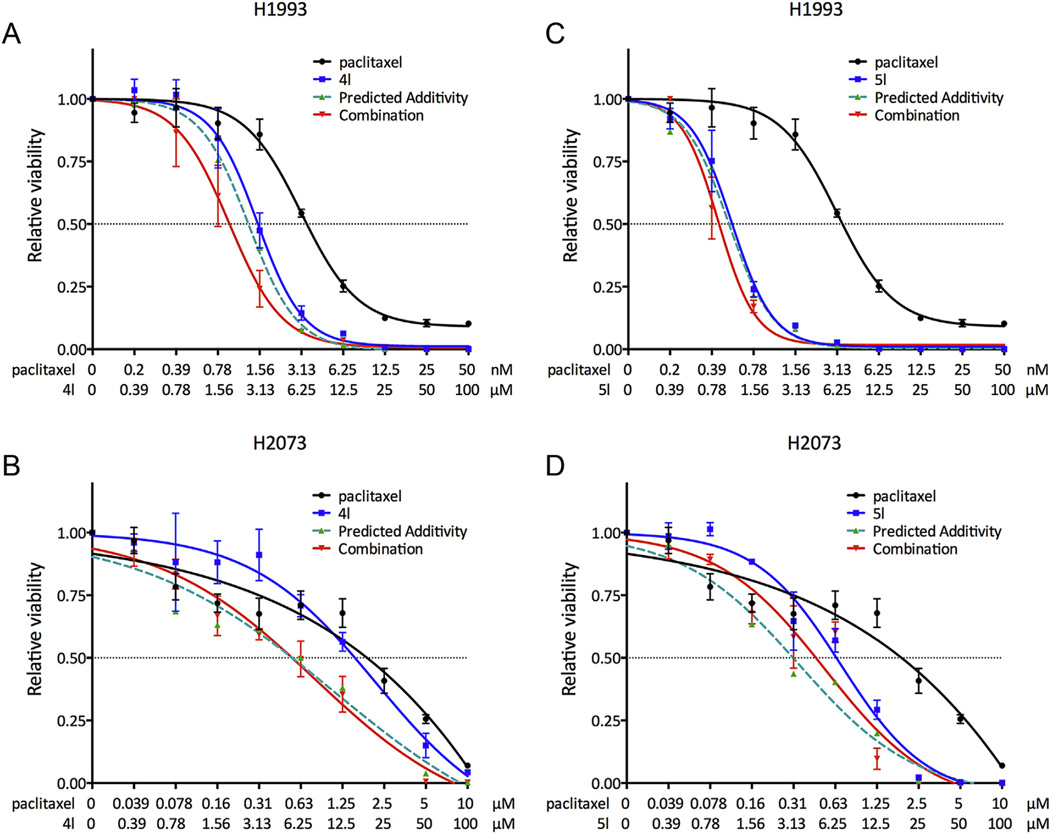

Further, spirodienone 4l and 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine 5l were evaluated against patient-derived NSCLC cell line H1993 and its drug-resistant variant H2073. The former was obtained from a lymph node metastasis isolated prior to chemotherapy, whereas the latter was derived from a regrown tumor at the primary site after the patient relapsed several months later [72]. Drug resistance of the H2073 cells is exemplified by the loss of responsiveness toward paclitaxel by several orders of magnitude relative to their H1993 counterparts (Table 3). Although the potencies of 4l and 5l also decrease against the H2073 cells, the drop is significantly less pronounced than that observed with paclitaxel (Table 3). Furthermore, it was found that both 4l and 5l synergize with paclitaxel in their antiproliferative action against the H1993 cell line (Fig. 3), indicating a potential use of these compounds as adjuvants to conventional chemotherapy for drug-resistant cancers.

Fig. 3.

Combination treatment of paclitaxel with 4l (A and B) and 5l (C and D) illustrating synergism against H1993 cells. H1993 is an NSCLC cell line and H2073 is its drug-resistant counterpart.

Finally, to assess whether our compounds are substrates for the MDR cancer efflux systems, 4l, 5l and 5g were evaluated against the MDR uterine sarcoma cell line MES-SA/Dx5. This cell line was established from the parent uterine sarcoma MES-SA, grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of doxorubicin and is known to be resistant to a number of P-gp substrates [73]. Both paclitaxel (Table 3) and vinblastine (not shown) displayed more than a thousand fold drop in potency when tested for antiproliferative activity against the MDR cell line as compared with the parent one. In contrast, there was only a small variation in the activities of our compounds, indicating their potential to overcome clinical multidrug resistance (Table 3).

2.2.3. Inhibition of translation

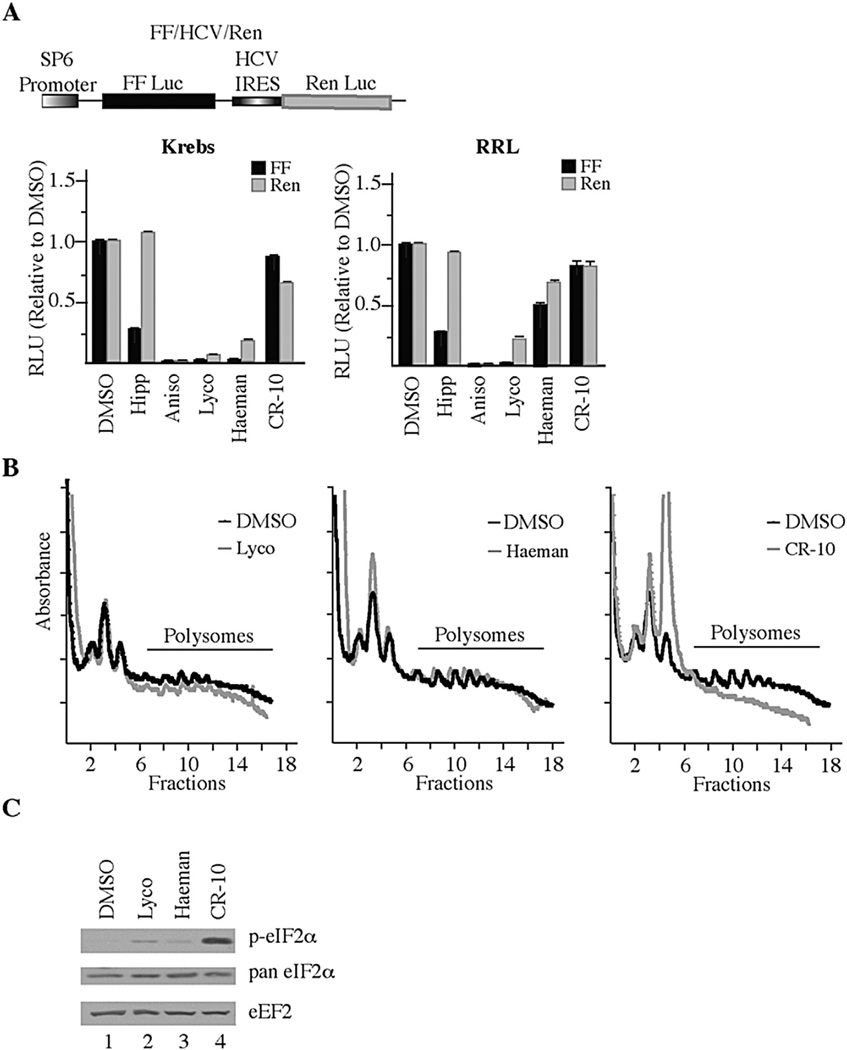

Because the earlier work revealed the translation inhibitory properties associated with the crinine-type alkaloids [45] it was important to test benzothiophene 5l in quantitative assays [74] assessing this biological activity (Fig. 4). As such, we performed in vitro translation assays in both Krebs-2 and rabbit reticulocyte lysates programmed with the bicistronic FF/HCV/Ren mRNA (Fig. 4A). Compared to previously characterized inhibitors of translation initiation (Hipp; hippuristanol) and elongation (Aniso; anisomycin, Lyco; lycorine, and Haeman; haemanthamine), 5l (CR-10) showed modest activity at inhibiting translation from both the FF (firefly) and Ren (renilla) cistrons (~25% inhibition). We then assessed the potency of 5l in vivo by monitoring poly-some profiles (Fig. 4B). The polysome distribution revealed that cells treated with lycorine and haemanthamine retained intact polysomes as previously reported for amaryllidaceae alkaloids which “freeze” polysomes and do not allow run-off or disaggregation of polysomes [45]. In contrast, 5l (CR-10) led to a complete disaggregation of polysomes (Fig. 4B). We then probed extracts from HeLa cells exposed to lycorine, haemanthamine, or 5l and found that 5l (CR-10) caused profound eIF2α phosphorylation, compared to vehicle, lycorine or haemanthamine (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that 5l is not an effective inhibitor of translation in vitro, but blocks translation in vivo by a mechanism that appears distinct from lycorine and haemanthamine involving eIF2α phosphorylation.

Fig. 4.

5l (CR-10) Blocks Translation Initiation. A. Effect of CR-10 on cap- and HCV- mediated in vitro translation in Krebs-2 extract and rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL). Upper panel: Schematic diagram of bicistronic mRNA used for in vitro translation assays. Lower panels: Krebs-2 translation extracts (left) or RRL (right) were programmed with FF/HCV/Ren mRNA and incubated with vehicle (0.5% DMSO) or the indicated compounds. The relative luciferase activity compared to the DMSO control from 2 independent translation reactions along with the error of the mean is presented. Reactions contained 1 µM hippuristanol (Hipp), 10 µM anisomycin (aniso), 50 µM lycorine (Lyco), 50 µM haemanthamine (Haeman), or 50 µM 5l (CR-10). B. Polysome profiling analyses of HeLa S3 cells exposed to 50 µM compound for 1 h. Polysomes for Lyco and 5l (CR-10) are from the same experiment so the DMSO control profile is the same in the two plots shown. C. 5l (CR-10) induces phosphorylation of eIF2α. HeLa S3 cells were treated with 50 µM compound for 1 h. Extracts were prepared, fractioned by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a Immobilon-P PVDF membrane. Western blots were performed with the antibodies directed to the indicated proteins.

3. Conclusion

Drug resistance is one of the main causes for the failure of cancer chemotherapy. It can be intrinsic, involving apoptosis-resistant cancers such as glioma, melanoma or NSCLC, among others, or acquired, in which tumors innately respond to chemotherapy but eventually become refractory to a broad spectrum of structurally and mechanistically diverse antitumor agents. The results presented herein demonstrate the potential of a synthetic collection of compounds inspired by the crinine group of the Amaryllidaceae alkaloids for the treatment of drug-resistant cancers, regardless of whether the latter harbor intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms. The structural scaffold associated with the benzothiophene ring system 5l represents a new chemotype, whose further investigation is warranted by the described findings and should be facilitated by the straightforward biomimetic synthetic methodology utilized in this study. The spirodienone ring system, such as in 4l, also represents an interesting structural type, which may serve as a prodrug of 5l, undergoing enzymatic removal of the trifluoroacetamide group with the subsequent intramolecular cyclization to produce 5l in the cell. Although direct proof of this hypothesis requires further studies, the similarity of the biological effects between structurally different 4l and 5l certainly strongly supports this argument. In addition to these experiments, the ongoing work includes optimization of potency, further elucidation of mechanisms responsible for cytostatic/cytotoxic effects in this series of compounds as well as studies involving animal models of drug-resistant human cancer.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General experimental

All reagents, solvents and catalysts were purchased from commercial sources (Acros Organics and Sigma-Aldrich) and used without purification. All reactions were performed in oven-dried flasks open to the atmosphere or under nitrogen or argon and monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) on TLC precoated (250 mm) silica gel 60 F254 glass-backed plates (EMD Chemicals Inc.). Visualization was accomplished with UV light. Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel (32–63 µm, 60 Å pore size). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm relative to the TMS internal standard. Abbreviations are as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet). The synthesized compounds are at least 95% pure according to an HPLC/MS analysis.

4.2. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 2a–h, 2j and 2l

To a flask containing 4.1 mmol of a selected aromatic aldehyde in 10.2 mL of methanol at 0 °C were added 0.7452 g (5.4 mmol) of tyramine. The solution was allowed to stir for 45 min and 0.1808 g (4.8 mmol) of sodium borohydride was added. The solution was allowed to stir for 4.5 h, at which point 0.1679 g (4.4 mmol) of additional sodium borohydride was added. This mixture was stirred overnight and the formed precipitate was collected via vacuum filtration. No further purification was required at this stage. The NMR spectral data for known compounds (2a [51], 2b [50], and 2e [50]) matched those in the literature. The characterization of all new compounds is given below.

4.3. Compound 2c

95%, white solid, mp: 91–93 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): d 6.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.78–6.66 (m, 5H), 4.22 (m, 4H), 3.69 (broad s, 2H), 2.84 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 154.6 (C), 143.4 (C), 142.6 (C), 132.9 (C), 131.1 (C), 129.8 (CHx2), 121.3 (CH), 117.2 (CHx2), 117.1 (CH), 115.6 (CH), 64.3 (CH2x2), 53.1 (CH2), 50.2 (CH2), 35.0 (CH2); HRMS calc'd for C17H20NO3 (M + H)+: 286.1438, found 286.1441.

4.4. Compound 2d

95%, white solid, mp: 89–91 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.89–6.65 (m, 5H), 5.81 (s, 2H), 5.46 (broad s, 1H), 3.79 (s, 2H), 2.85 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 156.1 (C), 147.3 (C), 145.5 (C), 129.9 (CHx2), 122.3 (C), 121.6 (C), 120.6 (CH), 116.3 (CHx2), 116.1 (CH), 107.8 (CH), 100.8 (CH2), 50.0 (CH2), 47.8 (CH2), 34.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C16H18NO3 (M + H)+: 272.1281, found 272.1286.

4.5. Compound 2f

97%, white solid, mp: 65–67 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): 7.40 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.70–6.68 (m, 3H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.70 (s, 2H), 2.84 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 154.4 (C), 149.8 (C), 147.2 (C), 137.4 (C), 133.2 (CHx2), 131.5 (C), 129.8 (C), 128.5 (C), 127.8 (CH), 127.3 (CHx2), 120.3 (CH), 115.4 (CHx2), 114.0 (CH), 112.0 (CH), 71.2 (CH2), 56.0 (CH3), 53.6 (CH2), 50.7 (CH2), 35.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C23H26NO (M + H)+: 364.1907, found 364.1912.

4.6. Compound 2h

95%, white solid, mp: 83–85 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.39–7.29 (m, 5H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.94 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 2H), 2.85 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.0 (C), 154.5 (C), 141.4 (C), 137.1 (CHx2), 131.4 (CHx2), 129.8 (CHx2), 129.5 (CH), 128.6 (C), 127.9 (C), 127.5 (CH), 120.8 (C), 115.5 (CHx2), 114.5 (CH), 113.6 (CH), 69.9 (CH2), 53.7 (CH2), 50.4 (CH2), 35.1 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C22H24NO2 (M + H)+: 334.1802 found 334.1807.

4.7. Compound 2j

60%, white solid, mp: 103–105 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (Acetone-d6): δ 7.32 (dd, J = 3.0, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 1.0, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (s, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.65 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 155.6 (C), 142.5 (C), 131.2 (CHx2), 129.5 (C), 127.7 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 120.9 (CH), 115.0 (CHx2), 51.0 (CH2), 48.4 (CH2), 35.4 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C13H16NOS (M + H)+: 234.0947, found 234.0952.

4.8. Compound 2l

89%, white solid, mp: 99–101 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.83–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.70–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 2.94 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 155.6 (C), 140.6 (C), 138.7 (C), 136.1 (C), 131.2 (CHx2), 129.6 (C), 124.2 (CH), 123.7 (CH), 122.6 (CH), 122.6 (CH), 122.3 (CH), 115.0 (CHx2), 51.3 (CH2), 47.3 (CH2), 35.4 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C17H18NOS (M + H)+: 284.1104, found 285.1108.

4.9. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 3a–h, 3j and 3l

To a dry flask containing 2.7 mmol of a selected amine 2a–l in 9.6 mL pyridine under argon were added 0.75 mL (5.2 mmol) of trifluoroacetic anhydride. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 1 day and quenched with 3 mL of methanol. The solution was concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in ethyl acetate, and washed twice with water and twice with brine. The solution was dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated in vacuo, and the desired product 3a–h, 3j and 3l was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/ ethyl acetate, 1.5:1). The NMR spectral data for known compounds (3a [75], 3b [50] and 3e [50]) matched those in the literature. The characterization of all new compounds is given below.

4.10. Compound 3c

82%, oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.99 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 2H), 6.95–6.58 (m, 5H), 5.46 (s, 1H), 4.51 (s, 1H), 4.26–4.22 (m, 5H), 3.45–3.41 (m, 2H), 2.78 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.1 (q, J = 34.9 Hz, C), 154.8 (C), 154.6 (C), 143.9 (C), 143.8 (C), 143.6 (C), 143.5 (C), 130.1 (C), 129.9 (C), 129.8 (C), 129.2 (C), 128.5 (CHx2), 127.8 (CHx2), 121.3 (CH), 120.6 (CH), 117.7 (CF3), 117.7 (CHx2), 117.1 (CHx2), 116.5 (CH), 115.8 (CH), 115.7 (CH), 115.6 (CH), 64.4 (CH2x2), 51.0 (CH2), 50.9 (CH2), 49.1 (CH2), 48.4 (CH2), 48.3 (CH2), 48.3, 34.3 (CH2), 34.1 (CH2), 31.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C19H18F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 404.1080, found 404.1085.

4.11. Compound 3d

80%, oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.99–6.96 (m, 2H), 6.81–6.72 (m, 5H), 5.94 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 5.23 (s, 1H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 4.43 (s, 1H), 3.49 (m, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.3 (q, J = 25.7 Hz, C), 155.0 (C), 154.8 (C), 147.6 (C), 147.4 (C), 146.0 (C), 145.8 (C), 129.9 (C), 129.8 (CH2), 129.7 (CH2), 129.0 (C), 122.3 (CH), 122.2 (CH), 121.0 (C), 118.1 (CH), 118.0 (CH), 116.7 (CH), 116.1 (CF3), 115.8 (CF3), 115.7 (CF3), 115.6 (CF3), 115.3 (CH2), 115.1 (CH2), 108.7 (CH), 108.6 (CH), 101.2 (CH2), 101.1 (CH2), 48.9 (CH2),, 48.7 (CH2), 46.0 (CH2), 45.9 (CH2), 44.2 (CH2), 34.2 (CH2), 31.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C18H16F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 390.0924, found, 390.0927.

4.12. Compound 3f

81%, oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.43 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.38–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 1H), 6.98–6.95 (m, 2H), 6.85 (dd, J = 6.6, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.79–6.70 (m, 3H), 6.65–6.61 (m, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.33 (s, 1H), 3.85 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 3H), 3.49–3.43 (m, 2H), 2.80 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H),13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.3 (q, J = 86.7 Hz, C)155.1 (C), 154.9 (C), 150.1 (C), 148.2 (C), 148.1 (C), 136.9 (C), 136.8 (C), 129.9 (CHx2), 129.7 (CHx2), 128.9 (C), 1, 128.6 (CHx2), 128.4 (CHx2), 128.0 (CH),, 127.5 (CHx2), 127.4 (CHx2), 120.8 (CH), 120.2 (CF3), 115.8 (CHx2), 114.1 (CH), 114.0 (CH), 111.9 (CH), 111.1 (CH), 71.1 (CH2), 56.1 (CH3), 56.0 (CH3),, 49.6 (CH2), 48.4 (CH2), 34.3 (CH2), 32.0 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C25H24F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 482.1550, found 482.1555.

4.13. Compound 3g

64%, white solid, mp: 45–47 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.42–7.26 (m, 10H), 7.03 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.4, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 6.86 (dd, J = 8.2, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 6.79–6.77 (m, 1H), 6.74–6.69 (m, 2H), 5.14 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 4.49 (s, 1H), 4.21 (s, 1H), 3.36–3.28 (m, 2H), 2.67 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.61 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 154.5 (C), 154.3 (C), 148.4 (q, J = 21.9 Hz, C), 137.1 (C), 137.0 (C), 136.9 (C), 130.4 (CH2), 129.9 (C), 129.8 (C), 129.5 (C), 128.6 (CHx2), 128.5 (CHx2), 128.0 (CH), 127.9 (CH), 127.7 (C), 127.4 (CHx2), 127.3 (CHx2), 121.4 (CH), 120.8 (CF3), 115.8 (CHx2), 115.6 (CHx2), 115.5 (CH), 115.1 (CH), 114.9 (CH), 114.5 (CH), 71.4 (CH2), 71.3 (CH2), 71.2 (CH2), 49.4 (CH2), 48.2 (CH2), 41.2 (CH2), 34.3 (CH2), 34.1 (CH2), 31.9 (CH2), 29.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C31H28F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 558.1863, found 558.1863.

4.14. Compound 3h

88%, oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.43–7.23 (m, 5H), 6.96–6.91 (m, 3H), 6.83–6.71 (m, 4H), 5.93 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 2H), 4.61 (s, 1H), 4.35 (s, 1H), 3.48–3.42 (m, 2H), 2.79–2.70 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.3 (C), 157.4 (C) (q, J = 33.9 Hz, C), 155.0 (C), 154.8 (C), 136.8 (C), 136.7 (C), 136.6 (C), 136.3 (C), 130.2 (C), 130.1 (C), 129.9 (CHx2), 129.8 (CHx2), 129.0 (CH), 128.7 (CH), 128.2 (CHx2), 128.1 (CHx2), 127.5 (CHx2), 120.6 (CH), 120.0 (CF3), 115.8 (CHx2), 115.7 (CHx2), 114.7 (CHx2), 114.6 (CHx2), 114.2 (CH), 70.2 (CH2), 70.1 (CH2), 51.52 (CH2), 51.49 (CH2), 49.8 (CH2), 48.7 (CH2), 34.3 (CH2), 31.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C24H22F3NNaO3 (M + Na)+: 452.1444, found 452.1448.

4.15. Compound 3j

77%, oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.33–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.98–6.9 (m, 2H), 6.78–6.74 (m, 2H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 4.37 (s, 1H), 3.51–3.45 (m, 2H), 2.79 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.70 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.0 (C) (q, J = 38.1 Hz, C), 154.8 (C), 154.6 (C), 135.9 (C), 135.7 (C), 130.0 (CHx2), 129.9 (CHx2), 129.8 (C), 129.2 (C), 127.5 (CH), 127.2 (CH), 126.9 (CH), 126.7 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 123.6 (CF3), 115.7 (CHx2), 115.6 (CHx2), 48.6 (CH2), 47.1 (CH2), 47.0 (CH2), 45.2 (CH2), 34.4 (CH2), 32.0 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C15H14F3NNaO2S (M + Na)+: 352.0590, found 352.0595.

4.16. Compound 3l

95%, oil; 1HNMR (CDCl3): δ 7.88–7.84 (m, 1H), 7.72–7.70 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 6.95–6.92 (m, 2H), 6.77–6.73 (m, 2H), 5.29 (broad s, 1H), 4.89 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 3.52 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.80–2.73 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 156.9 (q, J = 85.6 Hz, C) 154.8 (C), 154.7 (C), 140.7 (C), 140.5 (C), 137.6 (C), 137.3 (C), 130.0 (CHx2), 129.9 (CHx2), 129.8 (C), 129.6 (C), 129.1 (C), 126.0 (CH), 125.0 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 124.6 (CH), 123.2 (CH), 123.1 (CH), 121.6 (CH), 120.9 (CH), 118.1 (CH), 115.8 (CHx2), 115.6 (CHx2), 49.0 (CH2),, 48.2 (CH2), 46.3 (CH2), 46.2 (CH2), 43.6 (CH2), 34.5 (CH2), 32.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C19H16F3NNaO2S (M + Na)+: 402.0746, found 402.0752.

4.17. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 4a–l

To a dry flask containing 1.2 mmol of a selected coupling precursor 3a–l in 6 mL of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol under argon were added 0.5956 g (1.4 mmol) phenyliodine bis(trifluoroacetate) in dissolved in 6 mL of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. The reaction was stirred at −40 °C for 30 min and the solution was concentrated in vacuo. Purification by column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate, 2:1) yielded pure spirodienone 4a–l. The NMR spectral data for known compounds (4a [50], 4b [50] and 4e [50]) matched those in the literature. The characterization of all new compounds is given below.

4.18. Compound 4c

36%, white solid, mp: 71–73 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.00 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (s, 1H), 6.65 (s, 1H), 6.55 (s, 1H), 6.24 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 4.69 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.19–4.14 (m, 4H), 3.92–3.86 (m, 2H), 2.31 (tt, J = 17.5 Hz, 6.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.3 (C), 185.2 (C), 156.4 (q, J = 44.7 Hz, C), 152.8 (CHx2), 152.3 (CHx2), 143.4 (C), 143.3 (C), 142.8 (C), 129.0 (C), 128.9 (C), 128.5 (CH2), 128.4 (CH2), 127.2 (CF3), 127.0 (CF3), 120.2 (CH), 118.9 (CH), 118.6 (CH), 64.4 (CH2), 64.3 (CH2), 48.7 (CH2), 48.5 (CH2), 48.2 (C), 47.9 (CH2), 45.6 (CH2), 45.5 (CH2), 44.3 (CH2), 36.1 (CH2), 33.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C19H16F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 402.0924, found 402.0926.

4.19. Compound 4d

26%, white solid, mp: 147–149 °C (decomp.): 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.99 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.65–6.54 (m, 2H), 6.26–6.22 (m, 2H), 5.98 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 2H), 4.85 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 2H), 3.95–3.91 (m, 2H), 2.37–2.31 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.3 (C), 185.1 (C), 156.5 (q, J = 104.5 Hz, C), 152.5 (CHx2), 152.2 (CHx2), 146.9 (C), 146.7 (C), 146.5 (C), 146.0 (C), 129.9 (C), 129.8 (C), 127.1 (CHx2), 126.9 (CHx2), 123.5 (C), 123.1 (CH), 117.8 (CF3), 117.3 (CF3), 108.3 (CH), 108.1 (CH), 101.7 (CH2), 101.6 (CH2), 48.4 (C), 48.0 (C), 44.6 (CH2), 41.0 (CH2), 36.2 (CH2), 34.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C18H14F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 388.0767, found 388.0773.

4.20. Compound 4f

41%, white solid, mp: 109–111 °C (decomp.): 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.32–7.24 (m, 5H), 6.85 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 35.9 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (dd, J = 10.1, J = 3.1 Hz, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.73 (d, J = 14.6 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.86 (s, 2H), 2.33–2.27 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.1 (C),185.0 (C),156.4 (q, J = 36.6 Hz, C), 152.7 (CHx2), 152.3 (CHx2), 148.8 (C), 147.6 (C), 147.5 (C), 136.6 (C), 136.5 (C), 128.7 (CHx2), 128.6 (CHx2), 128.3 (C), 128.1 (C), 128.0 (CHx2), 127.8 (CHx2), 127.6 (CH), 127.4 (C), 127.3 (CF3), 127.2 (CHx2), 127.1 (CHx2), 116.1 (CH), 114.5 (CH), 113.5 (CH), 71.3 (CH2), 71.2 (CH2), 56.2 (CH2), 56.1 (CH2), 48.3 (C), 48.2 (C), 48.0 (C), 44.2 (CH3), 35.5 (CH2), 33.6 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C25H22F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 480.1393, found 480.1398.

4.21. Compound 4g

20%, white solid, mp: 79–79 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.43–7.24 (m, 10H), 6.87 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (dd, J = 9.9 Hz, J = 6.7 2H), 5.19 (s, 2H), 5.01 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 4.67 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 2H), 3.89–3.84 (m, 2H), 2.32–2.26 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.2 (C), 185.1 (C), 152.7 (CHx2), 152.3 (CHx2), 148.3 (C), 148.1 (q, J = 44.7 Hz, C), 136.7 (Cx2), 136.6 (Cx2), 128.6 (CHx4), 128.5 (CHx4), 128.4 (C), 128.3 (C), 128.2 (CHx2), 128.1 (CHx2), 128.0 (C), 127.4 (CHx2), 127.3 (CF3), 127.1 (CHx4), 117.1 (CH), 117.0 (CH), 116.8 (CH), 116.6 (CH), 71.4 (CH2), 71.4 (CH2), 71.3 (CH2), 71.2 (CH2), 48.3 (CH2), 48.2 (CH2), 48.0 (C), 44.2 (CH2), 35.5 (CH2), 33.6 (CH2), 29.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C31H26F3NNaO4 (M + Na)+: 556.1712, found 556.1715.

4.22. Compound 4h

21%, white solid, mp: 58–58.5 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.39–7.30 (m, 5H), 7.02–6.95 (m, 3H), 6.89 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 6.82–6.77 (m, 1H), 6.29–6.25 (m, 2H), 5.02 (s, 2H), 4.78 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.96–3.90 (m, 2H), 2.38–2.31 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.3 (C), 185.2 (C), 158.2 (C), 158.1 (C), 156.5 (q, J = 77.8 Hz, C), 152.8 (CHx2), 152.4 (CHx2), 136.7 (C), 136.5 (C), 136.4 (C), 131.7 (C), 131.2 (CH), 128.7 (CHx2), 128.2 (CH), 128.1 (CH), 127.5 (CHx2), 127.4 (CHx2), 127.3 (CHx2), 127.1 (CHx2), 117.8 (CF3), 117.0 (CH), 114.8 (CH), 114.7 (CH), 70.2 (CH2), 70.1 (CH2), 49.3 (CH2),49.1 (CH2), 48.2 (C), 47.9 (C), 45.6 (CH2), 45.5 (CH2), 44.5 (CH2), 36.1 (CH2), 34.0 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C24H20F3NNaO3 (M + Na)+: 450.1287, found 450.1292.

4.23. Compound 4i

11%, white solid, mp: 74–76 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.31–7.29 (m, 3H), 7.24–7.15 (m, 3H), 6.95–6.77 (m, 4H), 6.08 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 4.86 (s, 2H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 3.88–3.81 (m, 2H), 2.34–2.31 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 185.0 (C), 158.4 (C), 156.4 (q, J = 92.9 Hz, C), 153.5 (CHx2), 153.3 (CHx2), 137.4 (C), 137.3 (C), 135.4 (C), 135.3 (C), 129.1 (CH), 128.6 (CHx2), 128.3 (CH),127.9 (CHx2), 127.4 (CHx2), 125.3 (C), 125.0 (C), 123.8 (CH), 122.9 (CF3), 112.6 (CH), 112.5 (CH), 70.9 (CH2), 48.8 (CH2), 47.8 (CH2), 47.4 (CH2), 47.1 (CH2), 45.2 (CH2), 45.1 (CH2), 44.2 (CH2), 38.4 (C), 37.0 (C).

4.24. Compound 4l

41%, light yellow solid, mp: 89–92 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.84 (d, J = 8.1, 1H), 7.71 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.43–7.31 (m. 2H), 7.13–7.11 (m, 1H), 7.02–6.99 (m, 1H), 6.36–6.32 (m, 2H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 4.11–4.08 (m, 2H), 2.45–2.39 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 184.7 (C), 156.5 (q, J = 58.0 Hz, C), 150.0 (CHx2), 149.5 (CHx2), 140.2 (C), 139.5 (C), 138.8 (C), 138.3 (C), 137.8 (C), 130.3 (C), 129.8 (C), 128.6 (CHx2), 128.4 (CHx2), 125.3 (CH), 125.0 (CH), 124.8 (CH), 122.6 (CH), 122.4 (CH), 121.4 (CH), 121.0 (CF3), 46.0 (CH2), 45.7 (CH2), 45.6 (CH2), 45.0 (CH2), 42.8 (CH2), 41.9 (CH2), 37.5 (C), 35.7 (C). HRMS calc'd for C23H26F3NNaO2S (M + Na)+: 400.0590, found 400.0593.

4.25. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 5a–l

To a flask containing 0.15 mmol of a selected spirodienone 4a–m in 0.78 mL of methanol were added 0.8 mL of 10% aqueous potassium hydroxide at room temperature. The reaction was stirred for 30 min and the solution was extracted several times with chloroform. The organic layers were collected, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by column chromatography (chloroform/ methanol, 14:1) yielded the desired 5,10b-ethanophenanthridine 5a-5l. The NMR spectral data for known compounds (5a [54] and 5b [54]) matched those in the literature. The characterization of all new compounds is given below.

4.26. Compound 5c

66%, white solid, mp: 151–153 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.60 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 6.05 (d., J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 4.23–4.19 (m, 4H), 3.77 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 13.0 Hz, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.54–3.47 (m, 1H), 3.02–2.95 (m, 1H), 2.65 (dd, J = 16.8 Hz, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.44 (dd, J = 16.7 Hz, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.37–2.31 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.10 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 198.2 (C), 149.6 (CH), 142.3 (C), 142.1 (C), 136.0 (C), 128.7 (CH), 126.1 (C), 115.7 (CH), 110.7 (CH), 68.9 (CH), 64.5 (CH2), 64.4 (CH2), 61.3 (CH2), 54.0 (CH2), 44.6 (C), 44.3 (CH2), 40.1 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C17H18NO3 (M + H)+: 284.1281, found 284.1287.

4.27. Compound 5d

53%, white solid, mp: 155–157 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.65 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J =10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.05 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.62–3.51 (m, 2H), 3.04–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.70 (dd, J = 16.8 Hz, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (dd, J = 16.8 Hz, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.37–2.31 (m, 1H), 2.22–2.14 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 198.0 (C), 149.5 (CH), 145.8 (C), 145.1 (C), 137.3 (C), 128.5 (CH), 114.8 (C), 114.3 (CH), 106.4 (CH), 101.4 (CH2), 68.8 (CH), 56.9 (CH2), 54.3 (CH2), 44.8 (C), 44.7 (CH2), 40.1 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C16H16NO3 (M + H)+: 270.1125, found 270.1130.

4.28. Compound 5e

74%, white solid, mp: 149–151 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.73 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 6.13 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 4.39 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 3.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (t, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 3.06–2.99 (m, 1H), 2.73–2.65 (m, 1H), 2.50 (t, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H) 2.41 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H) 2.19–2.12 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 198.1 (C), 149.5 (CH), 148.4 (C), 147.4 (C), 137.0 (C), 135.5 (C), 128.8 (CHx2), 128.6 (CH), 127.9 (CH2), 127.3 (C), 125.3 (CH), 112.9 (CH), 106.4 (CH), 71.1 (CH), 68.9 (CH2), 61.5 (CH2) 56.5 (CH3), 54.1 (CH2), 44.8 (C), 44.5 (CH2), 40.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C23H24NO3 (M + H)+: 362.1751, found 362.1753.

4.29. Compound 5f

30%, white solid, mp: 67–69 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.54 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.38–7.33 (m, 1H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 6.06 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 4.43 (d, J =8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.83 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (dd, J = 5.7, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.55–3.52 (m, 1H), 3.03–2.99 (m, 1H), 2.68 (dd, J = 5.6, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (dd, J = 13.0, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H) 2.34–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.14 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 198.1 (C), 149.5 (CH), 149.0 (C), 146.8 (C), 137.1 (C), 134.8 (C), 128.8 (CHx2), 128.6 (CH), 128.0 (CHx2), 127.5 (C), 126.2 (CH), 110.8 (CH), 109.3 (CH), 72.0 (CH), 69.0 (CH2), 62.0 (CH2), 56.1 (CH3), 54.1 (CH2), 44.8 (C), 44.3 (CH2), 40.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C23H24NO3 (M + H)+: 362.1751, found 362.1756.

4.30. Compound 5g

30%, white solid, mp: 60–60.5 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.54 (d, J =10.3 Hz, 1H), 7.43–7.24 (m,10H), 6.96 (s,1H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 6.06 (d, J =10.3 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (s, 2H), 5.08 (s, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.66–3.61 (m, 1H), 3.59–3.52 (m, 1H), 3.01–2.98 (m, 1H), 2.71 (dd, J = 16.84, J = 2.86 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (dd, J = 13.02, J = 8.38 Hz, 1H), 2.34–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.18–2.13 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 197.8 (C), 149.1 (CH), 148.4 (C), 147.5 (C), 137.2 (C), 137.0 (C), 135.3 (C), 128.9 (CHx2), 128.6 (CHx2), 128.0 (CHx2), 127.9 (CHx2), 127.5 (C + CHx2), 127.3 (CH), 113.5 (CH), 110.3 (CH), 72.3 (CH), 71.2 (CH2), 68.8 (CH2), 61.3 (CH2), 54.0 (CH2), 44.5 (C), 39.9 (CH2), 29.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C29H28NO3 (M + H)+: 438.2064, found 438.2068.

4.31. Compound 5h

40%, white solid, mp: 103–105 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.70 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 7.41–7.29 (m, 6H), 6.81 (dd, J = 8.6, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (s, 2H), 4.43 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (dd, J = 5.4, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.60–3.50 (m, 1H), 3.04–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.66 (dd, J = 8.4, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (dd, J = 13.0, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.38–2.31 (m, 1H), 2.20–2.16 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 198.2 (C), 157.6 (C), 149.7 (CH), 136.9 (C), 135.4 (C), 135.0 (C), 128.7 (CHx2), 128.6 (CH), 128.0 (CHx2), 127.4 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 113.4 (CH), 113.1 (CH), 70.1 (CH), 69.0 (CH2), 62.0 (CH2), 54.2 (CH2), 44.8 (C), 44.4 (CH2), 40.2 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C22H22NO2 (M + H)+: 332.1645, found 332.1650.

4.32. Compound 5i

45%, white solid, mp: 62–63 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.64 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.33 (m, 5H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J =8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 4.48 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.69–3.62 (m, 2H), 3.57–3.50 (m, 1H), 2.97–2.89 (m, 1H), 2.65 (dd, J = 16.9, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 2.52–2.41 (m, 1H), 2.22–2.15 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 198.3 (C), 155.7 (C), 153.0 (CH), 139.6 (C), 135.9 (C), 131.0 (CH), 129.4 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 127.7 (CH), 127.6 (CH), 127.5 (C), 119.9 (CH), 111.0 (CH), 70.7 (CH), 69.7 (CH2), 61.9 (CH2), 54.2 (CH2), 46.0 (CH2), 43.4 (C), 40.5 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C22H22NO2 (M + H)+: 332.1645, found 332.1650.

4.33. Compound 5j

40%, white solid, mp: 114–116 °C (decomposes); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.34 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (dd, J = 12.7, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.61–3.55 (m, 1H), 3.04–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.74 (dd, J = 19.9, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.55–2.43 (m, 2H), 2.21–2.13 (m, 1H). 13CNMR (CDCl3): δ 197.7 (C), 145.0 (CH), 142.6 (C), 131.9 (C), 129.3 (CH), 126.2 (CH), 122.7 (CH), 70.2 (CH), 59.1 (CH2), 54.2 (CH2), 45.6 (CH2), 45.1 (C), 40.1 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C13H14NOS (M + H)+: 232.0791, found 232.0796.

4.34. Compound 5k

45%, white solid, mp: 118–119 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.53 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.58–3.47 (m, 2H), 3.01–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J =5.7, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.49 (t, J = 13.0, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.31–2.28 (m, 1H), 2.22–2.17 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.8 (C), 149.7 (CH), 144.8 (C), 133.9 (C), 128.7 (CH), 120.7 (CH), 115.4 (CH), 69.2 (CH), 58.4 (CH2), 53.5 (CH2), 46.1 (C), 43.3 (CH2), 39.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C13H14NOS (M + H)+: 232.0791, found 232.0796.

4.35. Compound 5l

74%, light yellow solid, mp: 143–145 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.82 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.30 (m. 2H), 6.11 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (d, J =16.6 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (dd, J = 12.9 Hz, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.67–3.60 (m, 1H), 3.09–3.01 (m, 1H), 2.78 (dd, J = 17.0 Hz, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.66–2.59 (m, 2H), 2.52 (dd, J = 16.9 Hz, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.25–2.18 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.7 (C), 149.7 (CH), 138.3 (C), 129.6 (C), 126.1 (C), 124.6 (C), 124.2 (CH), 122.9 (CH), 120.8 (CH), 70.7 (CH), 58.1 (CH), 54.6 (CH2), 45.9 (CH2), 45.0 (C), 40.3 (CH2), 29.3 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C17H16NOS (M + H)+: 282.0947, found 282.0952.

4.36. Preparation of compound 4m

This spirodienone was prepared by debenzylation of 4e as described in the literature [51]. Its NMR spectral data matched those in the cited report.

4.37. Preparation of compound 5m

This compound was prepared by detrifluoroacetylation of 4m as described in the literature [51]. Its NMR spectral data matched those in the cited report.

4.38. Preparation of compound 5n

To a dry flask containing 10.8 mg (0.040 mmol) of 5m in 0.3 mL of pyridine under nitrogen were added 20 µL (0.17 mmol) of benzoyl chloride and the reaction was allowed to stir for 2 days at room temperature. The mixture was quenched with 0.2 mL methanol and concentrated in vacuo. The crude was redissolved in chloroform and washed once with saturated sodium bicarbonate. The organic layer was filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by preparative TLC (chloroform/methanol, 15:1) yielded benzoate 5n (8.3 mg, 56%) as a white solid (mp: 205–207°C(decomp.)).1H NMR (CDC13): δ 8.20 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.88 (s, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.89–3.85 (m, 4H), 3.74 (dd, J = 5.0, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.61 (t, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 3.09–3.06 (m, 1H), 2.75 (dd, J = 5.0, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.57–2.46 (m, 2H), 2.28–2.23 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.9 (C), 164.8 (C), 150.0 (CH), 149.0 (C), 141.1 (C), 138.9 (C), 133.6 (CH), 130.3 (CHx2), 129.2 (C), 129.0 (CHx2), 128.6 (CH), 125.4 (C), 121.8 (CH), 106.5 (CH), 68.6 (CH), 61.0 (CH2), 56.2 (CH3), 54.1 (CH2), 44.9 (C), 44.7 (CH2), 40.0 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C23H22NO4 (M + H)+: 376.1549, found 376.1546.

4.39. Preparation of compound 5°

To a dry flask containing 3.0 mg (0.011 mmol) of 5m in 1.0 mL DMF under nitrogen were added 1.8 µL (0.016 mmol) of 5-hexynoic acid, 3.4 mg (0.016 mmol) of DCC and 1.0 mg (0.008 mmol) of DMAP at r. t. The reaction was stirred at rt for 20 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate and the organic layer was washed with sat. NaHCO3 solution and water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuo. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (chloroform/methanol, 24:1) and obtained pure 5o (3.1 mg, 76%) as a white solid (mp: 58–61 °C (decomp.)). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.67 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 3.92–3.84 (m,4H), 3.73 (dd, J = 13.1, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.69–3.59 (m, 1H), 3.13–3.01 (m, 1H), 2.85–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.59–2.40 (m, 2H), 2.36 (td, J = 7.0, 2.7 Hz, 2H), 2.29–2.19 (m, 1H), 2.01 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 197.3 (C), 171.3 (C), 150.0 (CH), 148.6 (C), 148.5 (C), 140.8 (C), 138.9 (CH), 129.3 (C), 121.8 (CH), 106.6 (CH), 83.3 (C), 69.4 (CH), 68.7 (CH), 60.9 (CH2), 56.3 (CH3), 54.1 (CH2), 45.0 (C), 44.4 (CH2), 39.8 (CH2), 32.8 (CH2), 23.9 (CH2), 17.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C22H24NO4 (M + H)+: 366.1705, found 366.1703.

4.40. Preparation of compound 5p

To a dry flask containing 15.9 mg (0.059 mmol) of 5m in 0.63 mL pyridine under argon were added 13 µL (0.14 mmol) of acetic anhydride at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to stir for 3.5 h, at which point 7 µL (0.074 mmol) of acetic anhydride were added every hour for 2 h. The reaction was quenched with methanol, concentrated in vacuo, and the crude was redissolved in chloroform. The solution was washed twice with water, twice with brine and the organic layer was filtered. Purification by preparative TLC (chloroform/ methanol, 14:1) yielded acetate 5o (11.3 mg, 62%) as a white solid (mp: 67–71 °C (decomp.)). 1H NMR (CDC13): δ 7.63 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (s, 1H), 6.67 (s, 1H), 6.05 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.82–3.73 (m, 4H), 3.61 (dd, J = 5.4, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.00–2.93 (m, 1H), 2.64 (dd, J = 5.1, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.35 (m, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H), 2.17–2.10 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.8 (C), 169.1 (C), 149.7 (CH), 149.0 (C), 141.1 (C), 138.6 (C), 129.0 (CH), 125.4 (C), 121.6 (CH), 106.4 (CH), 68.6 (CH), 60.9 (CH2), 56.1 (CH3), 54.1 (CH2), 44.8 (C), 44.6 (CH2), 30.9 (CH2), 20.6 (CH3). HRMS calc'd for C18H20NO4 (M + H)+: 314.1387, found 314.1391.

4.41. Preparation of compound 5q

To a solution containing 10.5 mg (0.039 mmol) of 5m in 0.5 mL of a pyridine/ethanol mixture (1:1) were added 5.5 mg (0.042 mmol) of hydroxyl ammonium sulfate over a steam bath. The solution was stirred for 1 h, at which point 9.6 mg (0.073 mmol) of additional hydroxyl ammonium sulfate was added. The solution was stirred for an additional hour and concentrated in vacuo. The crude was redissolved in ethanol, filtered, and the supernatant was purified by column chromatography (chloroform/methanol, 10:1, adjusted with ammonium hydroxide to pH 8). Oxime 5p was isolated as a white solid (7.8 mg, 70%, mp: 58–59 °C (decomp.)) as a mixture of geometric isomers. 1H NMR (CDC13): δ 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 6.25 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.84 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.65–3.32 (m, 3H), 2.97–2.92 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.04 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 155.3 (C), 145.2 (CH), 144.3 (C), 135.2 (C), 125.6 (C), 124.1 (CH), 123.1 (C), 112.9 (CH), 105.1 (CH), 66.4 (CH), 61.4 (CH2), 56.1 (CH3), 53.1 (CH2), 44.5 (C), 29.7 (CH2), 24.3 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C16H19N2O3 (M + H)+: 287.1396, found 287.1394.

4.42. Preparation of compounds 5r and 5s

To a flask containing 32.3 mg (0.11 mmol) of benzothiophene 5l in 0.65 mL of dichloromethane under nitrogen were added 38 µL of 30% hydrogen peroxide and 33 µL of acetonitrile. After stirring for 1.5 h at room temperature, 1.4 mL dichloromethane and 0.4 mL trifluoroacetic acid under were added and the mixture was allowed to stir for 1 day. The reaction was quenched with ammonium hydroxide and the product was extracted with chloroform. The organic layers were collected, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by preparative TLC (chloroform/methanol, 14:1) yielded sulfoxide 5q (11.6 mg, 34%, mp: 149–151 °C (decomposes)) and sulfone 5r (6.7 mg, 19%, mp: 143–145 °C (decomp.)) as white solids. 5q: 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.70 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.47 (m. 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 6.12 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (d, J = 18.6 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (s, 1H), 3.69–3.60 (m, 3H), 3.06–2.99 (m, 1H), 2.92–2.86 (m, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 17.0 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J = 16.9 Hz, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.24–2.17 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 196.4 (C), 145.5 (CH), 141.9 (C), 137.0 (C), 135.4 (C), 133.6 (CH), 130.3 (CH), 130.1 (CH), 121.4 (CH), 121.3 (C), 69.8 (CH), 56.4 (CH), 55.1 (CH2), 44.9 (CH2), 44.3 (C), 41.0 (CH2), 39.7 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C19H20NO2S (M + H)+: 298.0896, found 298.0905. 5r: 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.90 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.41 (m. 2H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.12 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (s, 1H), 3.70–3.60 (m, 2H), 3.57–3.52 (dd, J = 13.0 Hz, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.11–3.04 (m, 1H), 2.91–2.85 (m, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 17.0 Hz, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.49 (dd, J = 16.9 Hz, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.20 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.2 (C), 150.5 (CH), 148.2 (CH), 145.2 (C), 139.4 (C), 136.8 (C), 132.2 (C), 130.2 (CH), 128.7 (CH), 126.3 (CH), 121.5 (CH), 70.8 (CH), 57.4 (CH2), 55.4 (CH2), 45.1 (CH2), 44.7 (C), 40.1 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C19H20NO3S (M + H)+: 314.0846, found 314.0875.

4.43. Preparation of compound 5t

To a flask containing 48.3 mg (0.17 mmol) of ketone 5l in 2.5 mL ethyl acetate and 2 mL methanol were added 0.1341 g (0.36 mmol) of cerium trichloride heptahydrate and 13.6 mg (0.36 mmol) of sodium borohydride. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3.5 h at 0 °C and then filtered with through celite and the celite filter was washed with ethyl acetate and chloroform. The supernatant was concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in ethyl acetate, and washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate. The organic layer was then dried with sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by column chromatography (chloroform/methanol, 15:1–10:1) yielded alcohol 5s (33.1 mg, 68%) as a white solid (mp: 189–191 °C (decomp.)). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.79 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.24 (m. 2H), 6.19 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J =10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52–4.49 (m, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (d, J =16.5 Hz, 1H), 3.58–3.51 (m, 1H), 3.43 (dd, J = 13.3 Hz, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (broad s, 1H), 2.99–2.92 (m, 1H), 2.47–2.40 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.24 (m, 1H), 2.19–2.12 (m, 1H), 1.73–1.64 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 146.3 (C), 138.4 (C), 138.3 (C), 132.3 (C), 128.9 (CH), 124.7 (CH), 124.3 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 122.9 (CH), 120.4 (CH), 68.5 (CH), 67.9 (CH), 58.4 (CH2), 53.6 (CH2), 45.5 (C), 45.1 (CH2), 34.6 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C17H18NOS (M + H)+: 284.1104, found 284.1109.

4.44. Preparation of compound 5u

To a dry flask containing 16.7 mg (0.059 mmol) of alcohol 5s in 4 mL of dry THF were added 7.1 mg (0.18 mmol) of 60% sodium hydride dispersion in mineral oil. The reaction was allowed to stir at 0 °C for 1 h and 11 µL (25.1 mg, 0.18 mmol) of methyl iodide were added. The reaction mixture was stirred and allowed to warm to room temperature for 5.5 h, at which point saturated ammonium chloride was used to quench the reaction. The mixture was filtered and the supernatant was concentrated in vacuo. The compound was dissolved in methanol and filtered again. The supernatant was concentrated in vacuo to yield methyl ether (16.1 mg, 92%) as a white solid (mp: 231–233 °C (decomp.)) requiring no purification. 1HNMR (MeOD): δ 7.90 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 7.0 Hz, 1.0 Hz 1H), 7.45–7.36 (m. 2H), 6.11 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.96 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (s, 2H), 4.49–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.13–4.08 (m, 2H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 2.74–2.67 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.53 (m, 2H), 2.16–1.92 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (MeOD): δ 143.1 (C), 138.6 (C), 136.2 (C), 133.7 (C), 124.9 (CH), 124.9 (CH), 124.5 (CH), 122.6 (CH), 120.6 (CH), 119.6 (CH), 75.1 (CH), 68.0 (CH), 66.0 (CH2), 63.6 (C), 42.1 (CH2), 29.3 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C18H20NOS (M + H)+: 298.1260, found 298.1269.

4.45. Preparation of compound 5v

To a solution of 0.1657 g (0.46 mmol) of ketone 5e in 12.2 mL methanol were added 0.3583 g (0.96 mmol) of cerium trichloride heptahydrate and 34.9 mg (0.92 mmol) of sodium borohydride at 0 °C. The solution was stirred for 1.5 h and filtered through celite. The solution was concentrated in vacuo and purified by column chromatography (chloroform/methanol, 14:1) yielding alcohol 5v (0.1374 g, 82%) as a white solid (mp: 189–191 °C (decomp.)). 1H NMR (MeOD-d4): δ 7.41–7.27 (m, 5H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 6.53 (dd, J = 10.4, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.83 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (s, 2H), 4.65 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.41–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.19 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.82–3.74 (m, 1H), 3.37–3.30 (m, 1H), 2.34–2.24 (m, 3H), 1.781.70 (m, 1H), 1.12–1.10 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 149.3 (C), 147.5 (C), 137.0 (C), 135.3 (C), 132.2 (CH), 128.1 (CHx2), 127.6 (CH), 127.2 (CH), 125.8 (CHx2), 119.2 (C), 112.8 (CH), 106.8 (CH), 70.8 (CH2), 66.8 (CH), 65.7 (CH2), 59.0 (CH), 55.4 (CH3), 52.2 (CH2), 44.6 (C), 42.2 (CH2), 31.9 (CH2). HRMS calc'd for C23H26NO3 (M + H)+: 364.1907, found 364.1912.

4.46. Cell culture

Human cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), the European Collection of Cell Culture (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) and the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Human cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human mammary carcinoma MCF-7 cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. The U87 cells (ATCC HTB-14) were cultured in DMEM culture medium, while the A549 cells (DSMZ ACC107) were cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The GBM Hs683 (ATCC HTB-138) and the T98G (ATCC CRL-1690) cell lines were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The GBM U251 cells (ECACC code 09063001) were cultured in 10% MEM. The Human uterine sarcoma MES-SA and MES-SA/Dx5 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS with MES SA/Dx5 maintained in the presence of 500 nM Doxorubicin (Sigma). The U373 glioblastoma cells (ECACC 08061901) were cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cell culture media were supplemented with 4 mM glutamine (Lonza code BE17-605E), 100 µg/mL gentamicin (Lonza code 17–5182), and penicillin-streptomycin (200 units/ml and 200 µg/mL) (Lonza code 17–602E). Primary GBM-derived neurosphere cultures from a patient undergoing surgical debulking were established using previously described methods [76]. Briefly, resected tumor tissue was minced with a sterile scalpel and dissociated in 3 mL of neurobasal (NB) media containing 100 U/mL of collagenase (Life Technologies, USA) for 30 min at 37°. Dissociated tissue was then vortexed and filtered using a sterile 70 um nylon Falcon cell strainer (Corning, NY, USA). The filtered fraction was centrifuged at 200×g for 5 min and the pellet was transferred to a Corning ultra-low attachment plate containing neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with the following: B27 supplement (1X; Invitrogen), Glutamax (10ul/ml; Invitrogen), fibroblast growth factor-2 (20 ug/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), epidermal growth factor (20 ug/ml; Peprotech), heparin (32 ku/ml; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and penicillin-streptomycin (1X, Invitrogen). GBM 090909 and GBM 031810 cell lines were maintained in NB media containing supplements and media was renewed twice weekly. NSCLC cell lines H1993 and H2073 were obtained from the Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology Research at UT Southwestern Medical Center and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Mediatech, VA, USA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS (Mediatech, VA, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Sigma, MO, USA). All cell lines were cultured in T25 flasks, maintained and grown at 37° C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2.

4.47. Antiproliferative properties

Antiproliferative properties of the synthesized compounds were evaluated by the MTT assay. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of either 100 mM or 50 mM prior to cell treatment. The cells were trypsinized and seeded at various cell concentrations depending on the cell type. The cells were grown for 24 h–72 h, treated with compounds at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 100 µM and incubated for 48, 72 or 96 h in 100 or 200 µL media depending on the cell line used. The number of experiments and replicates varied depending on the cell line in Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 3. Cells treated with 0.1% DMSO were used as a negative control; 1 µM phenyl arsine oxide (PAO) was used as a positive control.

4.48. Selection of Doxorubicin Resistant Cells

Selection of Doxorubicin Resistant Cells. Selection of the MES-SA/Dx5 cell line was done according to Harker et al. [73] The cells were split and allowed to adhere overnight. The next day cells were initially exposed to a DOX concentration of 100 nM, which represented the GI50 concentration. The cells were maintained at this DOX concentration until their growth rate reached that of the untreated cells. The DOX concentration was then increased in twofold increments following the same growth criteria at each concentration to a final DOX concentration of 500 nM. Each new DOX concentration required approximately 2 passages to reach the growth rate of the untreated cells.

4.49. Evaluation of synergism of compounds 4l and 5l with paclitaxel

Paclitaxel (Teva, PA, USA) was dissolved in polyethoxylated castor oil. Compounds 4l and 5l were dissolved in DMSO. All compounds were diluted to different concentrations in medium. Appropriate numbers of cells (4 × 103 cells per well for H1993, 7 × 103 cells per well for H2073) were seeded into 96-well plates. The cells were grown for 24 h and treated with paclitaxel and either 4l or 5l, alone or in combination. After 96 h, viability of cells was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Predicted additivity was calculated based on Bliss Independence, as defined by Exy = Ex + Ey - ExEy, where Exy is the additive effect of drugs x and y as predicted by their individual effects Ex and Ey [77].

4.50. Quantitative translation assays

In vitro translation assays were performed as previously described [74]. Polysome profiling was as previously documented [74]. Antibodies for Western blots were directed to p-eIF2α, paneIF2 α, and eEF2 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103451), National Cancer Institute (CA186046-01A1), Welch Foundation (AI-0045), and National Science Foundation (NSF award 0946998). Work in J. Pelletier’s lab is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-106530, MOP-233466). SR and LF acknowledge their NMT Presidential Research Support. LF acknowledges Samantha Saville and National Science Foundation (NSF award IIA-1301346). XY, XM, and AP are grateful to the CPRIT Training Grant RP 140105. RK is a director of research with the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS; Belgium).

Abbreviations

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DSMZ

Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen and Zellkulturen

- ECACC

European Collection of Cell Culture

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- MGMT

O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PAO

phenyl arsine oxide

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- PODO

podophyllotoxin

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- PIFA

phenyliodine (III) bis(trifluoroacetate)

- TMZ

temozolomide

- TMS

tetramethylsilane

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

This manuscript is dedicated to Prof. Yuri I. Smushkevich on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.004.

References

- 1.Kelly GL, Strasser A. The essential role of evasion from cell death in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2011;111:39–96. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385524-4.00002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornienko A, Mathieu V, Rastogi S, Lefranc F, Kiss R. Therapeutic agents triggering non-apoptotic Cancer cell death. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:4823–4839. doi: 10.1021/jm400136m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefranc F, Brotchi J, Kiss R. Possible future issues in the treatment of glioblastomas: special emphasis on cell migration and the resistance of migrating glioblastoma cells to apoptosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:2411–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis HP, Greenslade M, Powell B, Spiteri I, Sottoriva A, Kurian KM. Current challenges in glioblastoma: intratumour heterogeneity, residual disease, and models to predict disease recurrence. Front. Oncol. 2015;5:251. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Networks (231 collaborators) Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2013;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agnihotri S, Burrell KE, Wolf A, Jalali S, Hawkins C, Rutka JT, Zadeh G. Glioblastoma, a brief review of history, molecular genetics, animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013;61:e25–e41. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R, Hottinger AF, van den Bent MJ, Dietrich PY, Brandes AA. Frequently asked questions in the medical management of high-grade glioma: a short guide with practical answers. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl. 7):209–216. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefranc F, Sadeghi N, Camby I, Metens T, De Witte O, Kiss R. Present and potential future issues in glioblastoma treatment. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:719–732. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes A, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross G, Mirimanof R-O. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner H. Long-term survival rates of cancer patients achieved by the end of the 20th century: a period analysis. Lancet. 2002;360:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saraswathy M, Gong SQ. Different strategies to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013;31:1397–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen GK, Duran GE, Mangili A, Beketic-Oreskovic L, Sikic BI. MDR1 activation is the predominant resistance mechanism selected by vinblastine in MES-SA cells. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:892–898. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geney R, Ungureanu M, Li D, Ojima I. Overcoming multidrug resistance in taxane chemotherapy. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2002;40:918–925. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartwell JL. Plants used against cancer. Lloydia. 1967;30:379–436. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin SF. The Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. In: Brossi AR, editor. The Alkaloids. Vol. 30. New York: Academic Press; 1987. p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshino O. The Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. In: Cordell GA, editor. The Alkaloids. Vol. 51. London: Academic Press; 1998. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook JW, Loudon JD. In: The Alkaloids. Manske RHF, Holmes HL, editors. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1952. p. 331. Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceriotti G. Narciclasine: an antimitotic substance from Narcissus bulbs. Nature. 1967;213:595. doi: 10.1038/213595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornienko A, Evidente A. Chemistry, biology, and medical potential of narciclasine and its congeners. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1982–2014. doi: 10.1021/cr078198u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Hu WX, He LF, Ye M, Li Y. Effects of lycorine on HL-60 cells via arresting cell cycle and inducing apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Li Y, Tang LJ, Zhang GP, Hu WX. Treatment of lycorine on SCID mice model with human APL cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2007;61:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu XS, Jiang J, Jiao XY, Wu YE, Lin JH, Cai YM. Lycorine induces apoptosis and down-regulation of MCL-1 in human leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;274:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLachlan A, Kekre N, McNulty J, Pandey S. Pancratistatin: a natural anti-cancer compound that targets mitochondria specifically in cancer cells to induce apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2005;10:619–630. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-1896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin C, Sharda N, Sood D, Nair J, McNulty J, Pandey S. Selective cytotoxicity of pancratistatin-related natural Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: evaluation of the activity of two new compounds. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vshyvenko S, Scattolon J, Hudlicky T, Romero AE, Kornienko A, Ma D, Griffin G, Pandey S. Unnatural C-1 homologues of pancratistatin: synthesis and promising biological activities. Can. J. Chem. 2012;90:932–943. doi: 10.1139/v2012-073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vshyvenko S, Scattolon J, Hudlicky T, Romero AE, Kornienko A. Synthesis of C-1 homologues of pancratistatin and their preliminary biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4750–4752. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins J, Rinner U, Moser M, Hudlicky T, Ghiviriga I, Romero AE, Kornienko A, Ma D, Griffin C, Pandey S. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of amaryllidaceae constituents and biological evaluation of their C-1 analogues. The next generation synthesis of 7-Deoxypancratistatin and trans-dihydrolycoricidine. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:3069–3084. doi: 10.1021/jo1003136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manpadi M, Kireev AS, Magedov IV, Altig J, Tongwa P, Antipin MY, Evidente A, van Otterlo WAL, Kornienko A. Synthesis of structurally simplified analogues of pancratistatin: truncation of the cyclitol ring. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:7122–7133. doi: 10.1021/jo901494r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Goietsenoven G, Hutton J, Becker JP, Lallemand B, Robert F, Lefranc F, Pirker C, Van den bussche G, Van Antwerpen P, Evidente A, Berger W, Prevost M, Pelletier J, Kiss R, Kinzy TG, Kornienko A, Mathieu V. Targeting of eEF1A with Amaryllidaceae isocarbostyrils as a strategy to combat melanomas. FASEB J. 2010;24:4575–4584. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-162263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Goietsenoven G, Andolfi A, Lallemand B, Cimmino A, Lamoral-Theys D, Gras T, Abou-Donia A, Dubois J, Lefranc F, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids belonging to different structural subgroups display activity against apoptosis-resistant cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1223–1227. doi: 10.1021/np9008255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamoral-Theys D, Decaestecker C, Mathieu V, Dubois J, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A, Pottier L. Lycorine and its derivatives for anticancer drug design. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010;10:41–50. doi: 10.2174/138955710791112604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamoral-Theys D, Andolfi A, Van Goietsenoven G, Cimmino A, Le Calvé B, Wauthoz N, Mégalizzi V, Gras T, Bruyère C, Dubois J, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. Lycorine, the main phenanthridine amaryllidaceae alkaloid, exhibits significant anti-tumor activity in cancer cells that display resistance to proapoptotic stimuli: an investigation of structure-activity relationship and mechanistic insight. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6244–6256. doi: 10.1021/jm901031h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evdokimov N, Lamoral-Theys D, Mathieu V, Andolfi A, Pelly S, van Otterlo W, Magedov I, Kiss R, Evidente A, Kornienko A. Search of a cytostatic agent derived from the alkaloid lycorine: synthesis and growth inhibitory properties of lycorine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:7252–7261. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Goietsenoven G, Mathieu V, Lefranc F, Kornienko A, Evidente A, Kiss R. Narciclasine as well as other amaryllidaceae isocarbostyrils are promising GTP-ase targeting agents against brain cancers. Med. Res. Rev. 2013;33:439–455. doi: 10.1002/med.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasari R, Banuls LMY, Masi M, Pelly SC, Mathieu V, Green IR, van Otterlo WAL, Evidente A, Kiss R, Kornienko A. C1,C2-Ether derivatives of the amaryllidaceae alkaloid lycorine: retention of activity of highly lipophilic analogues against apoptosis-resistant cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:923–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YH, Park EY, Park MH, Badarch U, Woldemichael GM, Beutler JA. Crinamine from Crinum asiaticum var. japonicum inhibits hypoxia inducible factor-1 activity but not activity of hypoxia inducible factor-2. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006;29:2140–2142. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin LZ, Hu SF, Chai HB, Pengsuparp T, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA, Ruangrungsi N. Lycorine alkaloids from hymenocallis littoralis. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:1295–1298. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00372-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hohmann J, Forgo P, Molnar J, Wolfard K, Molnar A, Thalhammer T, Mathe I, Sharples D. Antiproliferative Amaryllidaceae alkaloids isolated from the bulbs of Sprekelia formosissima and Hymenocallis x festalis. Planta Med. 2002;68:454–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furusawa E, Irie H, Combs D, Wildman WC. Therapeutic activity of pre-tazettine on Rauscher leukemia comparison with the related Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Chemotherapy. 1980;26:36–45. doi: 10.1159/000237881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]