Abstract

Background

This secondary analysis tested whether smokers’ perceived importance of willpower, ability to quit (i.e., self-efficacy), and use of treatment would prospectively predict occurrence of a quit attempt, duration of abstinence, or use of cessation aids

Methods

Smokers (n= 143) who planned to quit sometime in the next 3 months were asked whether, for most smokers, a) willpower is necessary for quitting, b) willpower is sufficient for quitting, c) they could quit anytime, d) they were too addicted to quit, and e) they thought use of aids indicated weakness of character. Smokers then reported quit attempts and abstinence daily for 3 months. No treatment was provided.

Results

The two willpower beliefs were often endorsed (78% and 60% each); the can quit any time and being too addicted beliefs were endorsed less consistently (12% and 35% each); and the belief that use of aids indicates a weakness was rarely endorsed (8%). The beliefs were only modestly correlated. Those who more strongly endorsed the two willpower beliefs or use of aids as a weakness were less likely to make a quit attempt. None of the constructs predicted duration of quit attempt. Seeing treatment as a weakness predicted less use of treatment.

Conclusions

The large majority of smokers believe willpower is necessary and sufficient for quitting and this belief appears to impede quit attempts. Given this is a post-hoc finding, replication tests are needed. If replicated, clinical and media interventions to combat willpower beliefs may increase quit attempts.

Keywords: Quit attempts, self-efficacy, smoking cessation, treatment use, willpower

1. Introduction

Lay conceptualizations of the determinants of the ability to stop drug use vary across drugs, cultures, and time periods 1. For example, currently concepts such as addiction, character, disease, habit, motivation, personality, self-control, self-efficacy, and willpower have been cited 2, 3. Perhaps the two most common concepts are willpower and self-efficacy 2,3,4,5,6,7 Current studies indicate ratings of one’s own willpower/motivation but not ratings of one’s own self-efficacy predict quit attempts. Conversely, ratings of self-efficacy but not willpower predict ability to remain abstinent 8, 9. In addition, some qualitative data indirectly suggests that thinking willpower is necessary decreases the probability of making a quit attempt and that thinking willpower is sufficient decreases the probability of using treatment 5.

We know of only two empirical studies that have assessed what smokers believe is important to quitting for smokers in general.. One of our studies found that lack of willpower was often endorsed as important both for stopping smoking, reducing alcohol use and reducing obesity 2. An Australian study proposed a more specific and detailed model; i.e., that many smokers hold five beliefs about smoking and that these beliefs act as barriers to quitting or using treatment 10. The beliefs were that a) willpower is necessary for quitting, b) willpower is sufficient for quitting, c) one can quit anytime they want to, d) one is too addicted to quit, and e) using aids to quit is a sign of weakness. The purpose of the current analyses was to determine if 1) most current US smokers endorse these beliefs, 2) the beliefs are correlated and 3) the beliefs prospectively predict the occurrence of quit attempts, duration of quit attempt (abstinence), and use of treatment. To test these five beliefs, we conducted a secondary analysis of data from one of our natural history studies of self-quitting.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

The methods of our natural history study are described in more detail in our prior publication 11. The study was approved by the University of Vermont Committee on the Use of Human Participants and was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00995644). In 2011–2013, we recruited smokers who intended to quit sometime in the near future to a prospective, phone-based observational study. Smokers reported the five beliefs at study entry. They then called an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system nightly for 3 months and reported quit attempts and abstinence. They reported on the five beliefs again at the end of the study.

2.2 Participants

Smokers were recruited via internet invitations. A typical message was “Daily cigarette smokers who intend to quit wanted for University of Vermont research study. Reimbursement for completing phone questions and mailed internet surveys. No need to leave home. This study does not offer treatment.” To obtain smokers likely to change their smoking in the next few months, we enriched the sample by enrolling only those who stated they probably or definitely intended to quit within the next 3 months. Other major inclusion criteria were: ≥ 18 years of age, smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes/day for at least 1 year, and did not use other forms of tobacco or nicotine.

Of the 153 participants who entered the study, all were from the US, 143 (94%) were smoking at study entry, and completed the baseline and were included in the analysis. Among these, 68% were women, 95% had completed high school, and 23% were minorities. Their mean age (sd) was 45 (12), mean cigarettes/day was 20 (10), and mean Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) score was 5.4 (2.2).

2.3. Procedures and Measures

The exact wordings of the belief questions are listed in Table 1. Likert scale response options were 1 = totally disagree, 3= neither agree nor disagree and 5 = totally agree. For brevity, we will refer to the first two beliefs as “willpower” beliefs, the next two as “self-efficacy” beliefs (note lower, not higher, scores for “too addicted to quit” are used to indicate higher self-efficacy) and the last belief as “treatment belief”. Our measure of quit attempts included attempts that did not last a day. Our measure of duration of abstinence was the longest duration of abstinence after a quit attempt. Our measure of treatment use was from an end-of-study retrospective recall of treatment use at some point during the study.

Table 1.

Questions, labels and prevalence of endorsement of the five beliefs

| Question | Label | Prevalence, Current Study (US, 2009) | Prevalence, Prior Study (Australia, 2002) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willpower | |||

| There is no point in trying to quit unless you want to. | Will Power is Necessary | 78% | 84% |

| To quit successfully, you really have to want to, then you’ll just do it. | Will Power is Sufficient | 60% | 80% |

| Self-Efficacy | |||

| I can quit anytime I want to. | Can Quit Anytime | 13% | 25% |

| I am too addicted to be able to quit. | Too Addicted to Quit | 35% | 34% |

| Use of Aids is a Weakness | |||

| Using aids to quit is a sign of weakness, if you really want to quit then you will do it by yourself. | Use of Aids is Weakness | 8% | 35% |

3. Results

3.1 Compliance

Few (6%) participants dropped out of the study; i.e., did not complete the last week of IVR calls. Across the 12,012 potential days of IVR data (143 participants x 84 days), 95% of the calls were completed.

3.2 Prevalence of Endorsements and Inter-Correlations Among Beliefs

The majority of smokers endorsed willpower as being necessary or as being sufficient to quit; i.e., scored 4 or 5 on the Likert scale (Table 1). Half stated (48%) said willpower was both necessary and sufficient. Few stated they could quit anytime; few stated they were too addicted to quit; and very few saw medication use as a weakness. Willpower, self-efficacy and treatment use beliefs were only modestly correlated (absolute values for Spearman r = .02–.28; see Appendix, Table 1). Beliefs at study entry only moderately agreed with beliefs at study exit (Weighted Kappa = .18 – .42 across the five beliefs).

Appendix, Table 1.

Spearman Correlations Among Beliefs

| Willpower is Sufficient | Can Quit Anytime | Too Addicted to Quit | Aids as Weakness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willpower is Necessary | 0.19* | −0.02 | −0.13 | −0.06 |

| Willpower is Sufficient | 0.28*** | −0.26** | 0.19* | |

| Can Quit Anytime | −0.28*** | 0.22** | ||

| Too Addicted to Quit | −0.08 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

3.3 Beliefs as Prospective Predictors of Quit Attempts, Duration of Abstinence, and Treatment Use

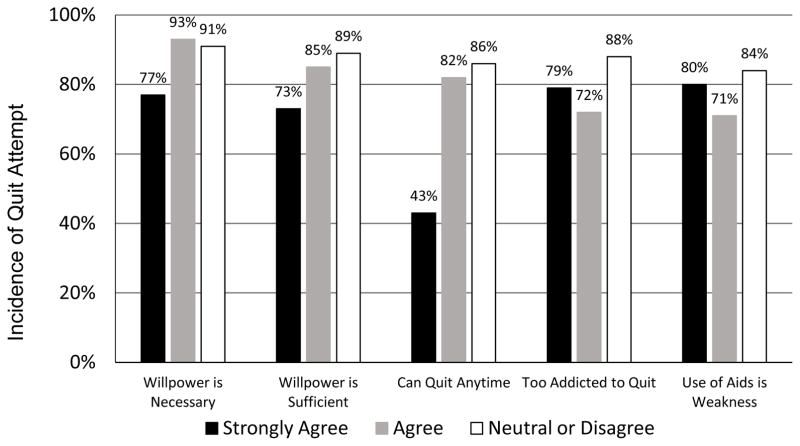

Overall, 83% of participants made a quit attempt. Smokers who more strongly endorsed Willpower is Necessary (Kruskal Wallis, p = .03), Will Power is Sufficient (p = .01), and Use of Aids is a Weakness (p = .004) beliefs, were less likely to make a quit attempt (but self-efficacy beliefs did not predict quit attempts (Figure 1)). None of the beliefs predicted the longest duration of abstinence among quit attempters; however only 41% of attempts lasted a day or more. Overall 63% used a treatment during the study. Neither willpower is sufficient nor self-efficacy beliefs predicted use of treatment. Those who endorsed use of aids as a weakness were less likely to use treatment (KW, p = .004).

Figure 1.

Incidence of Quit Attempt by Baseline Agreement with Belief

3.4 Predictors of Belief Ratings

We examined the following predictors of the five beliefs: age, sex, race, education, marital status, dependence (via cigarettes/day, time to first cigarette, Fagerstrom score, and self-rated addiction), when plan to quit in the future, self-efficacy, benefits of smoking, barriers to smoking (Appendix, Table 2).The positive results (p < .05) were a) the Willpower is Necessary belief was endorsed more by dependent smokers, b) the Willpower is Sufficient belief was endorsed more by those with high self-efficacy, c) the Can Quit Anytime belief was endorsed more by unmarried, minorities, less dependent, and those who plan to quit sooner, those with higher self-efficacy and those with fewer perceived barriers d) the Too Addicted to Quit belief was endorsed more by those who those who did not plan to quit till later, rated more barriers to quitting and had lower self-efficacy, and e) the Aids as Weakness belief was endorsed more by men than women. None of the baseline variables moderated the association of beliefs with cessation.

Appendix, Table 2.

Baseline Predictors of Beliefsa

| Willpower is Necessary | Willpower is Sufficient | Can Quit Anytime | Too Addicted to Quit | Aids as Weakness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | |||||

| Gender | Men>Women KW** |

||||

| Minority | Minorities>Whites KW** |

||||

| Education | |||||

| Marital status | Never married>Married KW* |

||||

| Smoking | |||||

| Cigs/day | More> Less r=.17* |

Less> More r= −.20* |

|||

| Time-to-1st cigarette | Shorter>Longer r = −.19 |

More > Less r= .20* | |||

| FTCD | Higher>Lower r=.20* |

Lower > Higher r= − .21* | |||

| Self-rated addiction | Lower>Higher r=.35*** |

Higher>Lower r=.20* |

|||

| When Plan to quit | Longer>Shorter r=.25** |

||||

| Self-efficacy | Higher >Lower r=.21* |

Higher>Lower r=.32*** |

Lower>Higher r= −.40*** |

||

| Benefits of quitting | |||||

| Barriers to quitting | Less>More r=−.29*** |

More>Less r= .18* |

|||

FTCD =Fagerstrom Test for Tobacco Dependence, KW =Kruskal-Wallis, r = Spearman correlation coefficient

Cells represent effect of row variable on column outcome; e.g., men were more likely to endorse aids as weakness than women, and heavier smokers were more likely to endorse willpower is necessary than lighter smokers

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < 001

4. Discussion

We would remind readers that the beliefs we examined did not ask smokers to rate their own motivation or self-efficacy. Instead we asked smokers how important they believed willpower and self-efficacy are to smoking cessation among most smokers. Most participants (60–78%) believed willpower was important to quitting. This prevalence is similar to that found in the Australian study 10 and other studies 5, 12. Endorsing the importance of willpower prospectively predicted a smaller incidence of quit attempts. One interpretation of this is that willpower beliefs undermine quit attempts; i.e., smokers who endorse willpower beliefs believe there is no need to try to quit until one has sufficient willpower. The belief that willpower is necessary or sufficient was not associated with the duration of a quit attempt. This result is consistent with several recent studies that have found cessation beliefs predict making a quit attempt but do not predict remaining abstinent 8, 9. Willpower was not associated with treatment use. Although smokers often state treatment is not needed if a high level of willpower is present 5, 12, the only study that examined if willpower predicts actual use of treatment was our prior study 2 which also found willpower was not predictive of treatment use.

Similar to the Australian study, beliefs that self-efficacy is important occurred but were less prevalent than willpower beliefs (39%–42%). Self-efficacy did not predict quit attempts, duration of abstinence or treatment use. Our rate of endorsing treatment use as a weakness was much lower than the Australian study. This could be because our study is more recent and acceptance of treatment has increased over time.

The major asset of our study was the use of a true prospective test of whether these beliefs predicted actual quitting behavior. Perhaps the most important limitation of the present study is that the Australian scale we used was comprised of only one or two questions to assess each belief. Smokers’ conceptualizations of willpower, self-efficacy and treatment as a weakness may be so heterogeneous that they require multi-item scales to adequately measure. For example, although we have interpreted the first two questions as representing willpower, other descriptors such as ability, cognitive effort, desire, duty, enthusiasm, intention to quit, priority, reasons for quitting, seriousness, and commitment could have been used 13–16,4. Also, it may be that most smokers have put very little thought into their definitions of willpower or self-efficacy 17. A second limitation is that we used a convenience sample of smokers who planned to quit at some point in the near future. A third is that we had few smokers who abstained for significant periods of time, thereby limiting our ability to predict cessation success. Another limitation is that, although we did not explicitly ask about smokers’ beliefs about the importance of willpower, etc. to their own quitting, it is likely such beliefs influenced their ratings2. Given these limitations, and the paucity of prior tests of whether beliefs actually influence behavior, replication tests are indicated.

Our study results suggest over-reliance on willpower may be one factor in undermining quit attempts. If this finding is replicated, then strategies to combat this belief could be developed and may increase quit attempts. However, we were struck with the absence of prior studies testing whether beliefs about smoking cessation actually predict future quitting and the absence of any clear consensus about which beliefs, if any, are important 5, 18. We believe both qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand and measure cessation beliefs and to more rigorously test whether these beliefs actually predict quitting and treatment use.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Most smokers believe willpower is necessary or sufficient for quitting

Believing willpower is necessary or sufficient appears to undermine quit attempts

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This analysis was funded by research grant 1 R01 DA025089 from the US National Institutes of Health. The sponsor had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing or submission of the manuscript.

The authors thank Peter Callas, James Fingar, Saul Shiffman and Laura Solomon for help in designing the study; Emily Casey, Ginger Cloud, Miki Dash, Tonya Ferraro, James Fingar, Matthew MacKinnon, Sharon Muellers, Adam Rhodes-Ragon, and Beth Walsh for help in conducting the study; James Balmford, Ron Borland, and Laura Solomon for help with interpretation of results; and Jessie McNabb for preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have conflicts

Contributors: JH designed the study, obtained funding and oversaw conduct of the study. Both authors participated in data analysis and writing of the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Peele S. Diseasing of America: Addiction Treatment Out of Control. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes J. Smokers’ beliefs about the inability to stop smoking. Addict Behav. 2009;34:1005–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter G. Spontaneous remission from alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse: Seeking quantitative answers to qualitative questions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:443–460. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AL, Carter SM, Dunlop SM, Freeman B, Chapman S. The views and experiences of smokers who quit smoking unassisted. A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127144. (5ee0127144) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzelepis F, Paul CL, Walsh RA, Knight J, Wiggers J. Who enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of quitline support? Comparison of participants versus nonparticipants. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15:2107–2113. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heather N. Public attitudes to the disease concept of alcoholism. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1987;22(11):1129–1138. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haaga D, Gillis M, McDermut W. Lay beliefs about the causes and consequences of smoking cessation maintenance. International Journal of Addictions. 1993;28:369–375. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borland R, Yong H-H, Balmford J, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Project. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:S4–S11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balmford J, Borland R. What does it mean to want to quit? Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:21–27. doi: 10.1080/09595230701710829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Naud S, Fingar J, Helzer JE, Callas P. Natural history of attempts to stop smoking. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2014;16:1190–1198. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook-Shimanek M, Levinson AH, burns E. Medicinal nicotine nonuse: smokers’ rationales for past behavior and intentions to try medicinal nicotine in a future quit attempt. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15:1926–1933. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Predictive validity of the Motivation To Stop Scale (MTSS): A single-item measure of motivation to stop smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmons VN, Heckman BW, Ditre JW, Brandon TH. A measure of smoking abstinence-related motivational engagement: Development and initial validation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:432–437. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahler CW, LaChance HR, Strong DR, Ramsey SE, Monti PM, Brown RA. The Commitment to Quitting Smoking Scale: Initial validation in a smoking cessation trial for heavy social drinkers. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2420–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:175–181. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nisbett R, Wilson T. Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review. 1977;84:231–259. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers MG, Strong DR, Linke SE, Hofstetter CR. Predicting use of assistance with quitting: A longitudinal study of the role of quitting beliefs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]