Abstract

Intentional exposures to toxic chemicals can stem from terrorist attacks, such as the release of sarin in the Tokyo subway system in 1995, as well as from toxic industrial accidents that are much more common. Developing effective medical interventions is a critical component of the overall strategy to overcome the challenges of chemical emergencies. These challenges include the rapid and lethal mode of action of many toxic chemicals that require equally fast-acting therapies, the large number of chemicals that are considered threats, and the diverse demographics and vulnerabilities of those who may be affected. In addition, there may be long-term deleterious effects in survivors of a chemical exposure. Several U.S. federal agencies are invested in efforts to improve preparedness and response capabilities during and after chemical emergencies. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats (CounterACT) Program supports investigators who are developing therapeutics to reduce mortality and morbidity from chemical exposures. The program awards grants to individual laboratories and includes contract resource facilities and interagency agreements with Department of Defense laboratories. The range of high-quality research within the NIH CounterACT Program network will be discussed.

Keywords: chemical threats, chemical emergencies, therapeutics, NIH CounterACT

The burden of illness caused by chemical exposures

Chemicals are an integral part of modern civilization and certain chemical elements are essential for the survival of all living species. Chemicals vary in their toxicity to plants and animals, which is an advantage in many cases where they are designed to be toxic for one species and not another (e.g., for pesticides), or even one cell type and not another (e.g., for chemotherapeutics). Exposure to toxic chemicals can be accidental or intentional, and, depending on the dose received, the exposures can be fatal, cause major or minor illness, or not be harmful at all. The burden of illness to humans caused by toxic chemicals is significant and can be due to both intentional and accidental exposures (Fig. 1).

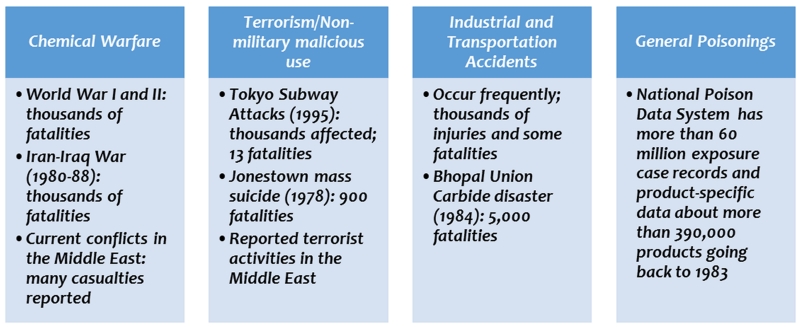

Figure 1.

The burden of illness caused by acute exposures to toxic chemicals.

Chemical warfare agents (CWAs) are highly toxic chemicals, such as sarin nerve agent and the vesicant agent sulfur mustard, which were used in World Wars I and II, and nearly 45 types of toxic chemicals were used in World War I alone.1 A very large number of fatalities and lasting injuries occurred after the use of CWAs in the Iran–Iraq and Afghanistan wars in the 1980s.2 Following a relatively long absence of CWAs in warfare, there has recently been a resurgence of their use in conflicts in the Middle East. For example, in August 2013, sarin was released in Damascus, Syria, resulting in the deaths of 1400 civilians and severe injuries to thousands. These chemical attacks affected all demographics, including pregnant women and their unborn children,3 and illustrate the importance of developing better medical interventions.4

The burden of illness also stems from other types of intentional exposures, most notably terrorist attacks involving CWAs and other toxic chemicals. One of the most infamous attacks of this nature occurred in 1995 when members of the terrorist group Aum Shinrikyo released sarin in the Tokyo subway system,5 resulting in fatalities and short- and long-term illnesses of varying degrees.6 Unintentional exposure to toxic chemicals is much more common and represents the greatest burden of illness. Toxic industrial chemicals (TICs), such as cyanide, chlorine, and ammonia acids, are manufactured and stored in large volumes at industrial facilities and transported across the United States for various uses. Agricultural chemicals of concern include insecticides, such as parathion, and rodenticides, such as tetramethylenedisulfotetramine (TETS). The threat from these chemicals comes from their use as weapons, as well as from potential unintentional releases due to industrial and occupational accidents or natural disasters, such as earthquakes and hurricanes.

The challenge of managing chemical emergencies

There are several factors that make chemical emergencies difficult to manage. First, most toxic chemicals have rapid modes of action and can be lethal within minutes, depending on the level of exposure and how quickly effective medical intervention can occur. Some chemicals, such as nerve agents, after inhalation can penetrate rapidly and reach critical sites within the central and peripheral nervous systems, causing death. Owing to the rapid mode of target engagement and activation (or inhibition), medical interventions are often too late because of the time required to respond from remote sites and treat patients safely either in the field or in hospital emergency departments. Researchers are therefore focused on developing therapeutics that can be delivered rapidly in the field, such as by intramuscular injection, orally, or by intranasal administration when appropriate. Other exposures that have a slower mode of action, such as dermal exposure to sulfur mustard, offer a larger window of opportunity for medical intervention, but these injuries can be difficult to treat because of the slower and insidious nature of the injury after the chemical is absorbed through the skin. In this case researchers are focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the injury to develop specific mechanism-based therapeutics that do not necessarily need to be administered immediately after the exposure in order to prevent mortality.

A second challenge related to medical countermeasure development is the sheer number of potential toxic chemicals that could be used by terrorists or released by accident and cause harm. Chemical threat agents of particular interest include CWAs (e.g., sarin, sulfur mustard), TICs (e.g., cyanide, chlorine), pesticides (e.g., parathion, aldicarb), and other chemicals. Classes of chemical threats encompass cholinesterase and neurotransmitter inhibitors that can induce prolonged and uncontrolled excitation of the nervous system; metabolic/cellular poisons that prevent cellular respiration; vesicating agents that cause moderate to debilitating ocular, dermal, and mucosal injuries; and pulmonary compounds that corrosively injure, irritate, or react with the lining of the respiratory tract. Because the one chemical–one antidote model is not feasible to use for the vast number of toxic chemicals that pose a threat, the best approach for researchers is to strive for the development of medical countermeasures that can be used for more than one chemical agent, perhaps classes of agents that have similar targets and/or clinical effects.

Finally, it is well known that toxic chemicals have different effects on different demographic segments of the population. Special consideration is given to people who are particularly vulnerable, including pregnant women, infants, the young, the elderly, and individuals with preexisting medical conditions. Many chemical agents are more toxic when exposure occurs during development in utero or during childhood, owing to a number of factors such as immature detoxification capacity and greater exposure relative to adults. Preexisting conditions, such as asthma, can predispose individuals to greater toxicity from exposure to pulmonary agents, such as chlorine or ammonia.

The problem of long-term effects

The level of potential exposure after most large-scale chemical releases is heterogeneous, with individuals nearest the point source being exposed to high levels and many deaths may occur. Some individuals exposed to lower levels may survive, but experience serious nonlethal acute effects and longer-term pathological sequelae that may occur days, weeks, or years later. Using sarin as an example, multiple reports show that victims who were exposed to sarin in the Matsumoto and Tokyo subway attacks may have suffered long-term neurological effects, including behavioral abnormalities and alteration of brain morphology.5-7 In nonhuman primates, specifically rhesus monkeys, significant and persistent increases have been shown in the relative amount of high-frequency beta activity, as measured by an electroencephalogram (EEG), 1 year following sarin exposure.8 One representative study of numerous studies in rats showed that, at 3 months after exposure to a single non-convulsive symptomatic dose of sarin for 60 min in an inhalation chamber, a significant alteration was observed in the performance of exposed rats in a functional observatory battery (FOB), characterized by changes in mobile activity and gait, and an increase in stereotypic behavior.9

The challenge in studying long-term effects is in developing appropriate animal models based on the best available data from human exposures so that treatments can be developed for the effects of these exposures, in the same way that neuroprotectants are being developed to treat patients after stroke, status epilepticus, and other brain injuries. The question of whether researchers can develop these animal models, among other related questions, was discussed at a workshop convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats (CounterACT) Program and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in February 2014 (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/research/counterterrorism/2014-NIH-Workshop-on-Nerve-Agents.pdf) and forms the impetus for current efforts to conduct a systematic review of the literature to date that would evaluate the evidence that long-term neurological effects may follow acute exposure to sarin. Another challenge in developing animal models is the steep dose–response relationship for many of the most important chemical threats. For example, the nerve agent VX is lethal to 100% of guinea pigs after 24 h at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg, but VX does not cause mortality at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg (unpublished data). This is mostly a problem when trying to develop animal models that exhibit the desired toxicity but survive that toxicity long enough to test a potential therapeutic.

Efforts to address chemical exposure in public health emergencies

Several U.S. federal agencies are invested in efforts to develop medical countermeasures to be used in the event of an emergency that involves the use of chemical agents. For example, the Department of Defense (DoD) has led the way for decades in developing therapeutics and other countermeasures for chemical exposures on the battlefield. The NIH CounterACT Program works in close partnership with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (MRICD) to leverage their extensive experience and expertise. After the events of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. government has increased efforts to be prepared to respond to the use of chemical agents on civilians. The Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Health and Human Services (DHHS) have programs dedicated to this effort, including the NIH CounterACT program, and participate in publications such as this special issue on countermeasures against chemical threats. Led by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE) coordinates federal efforts to enhance chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats and emerging infectious diseases preparedness. The 2015 PHEMCE Strategy and Implementation Plan (http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/mcm/phemce/Documents/2015-PHEMCE-SIP.pdf) outlines the overall effort coordinated within the federal government. Another key partner of the NIH CounterACT Program is the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which supports advanced development of therapeutic products (http://www.phe.gov/about/BARDA/Pages/default.aspx), many of which are transitioned from programs supported under the NIH CounterACT Program.

The NIH CounterACT Program

The NIH CounterACT Program is part of the larger NIH Biodefense Program coordinated by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which also includes biological and radiation/nuclear threats. Antidotes that are specific to a chemical are desired; however, the program is also interested in developing therapeutics that have a broader spectrum of activity against more than one chemical, since many acute effects and pathologies are common to several chemical threat agents. The NIH CounterACT Program is led by the NINDS, but is a trans-NIH effort with many of the projects being managed by other institutes, including the National Eye Institute (NEI), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). The program receives expert advice from other NIH institutes; the multidisciplinary collaboration is the key to the program’s success since chemical exposure affects so many different aspects of human health.

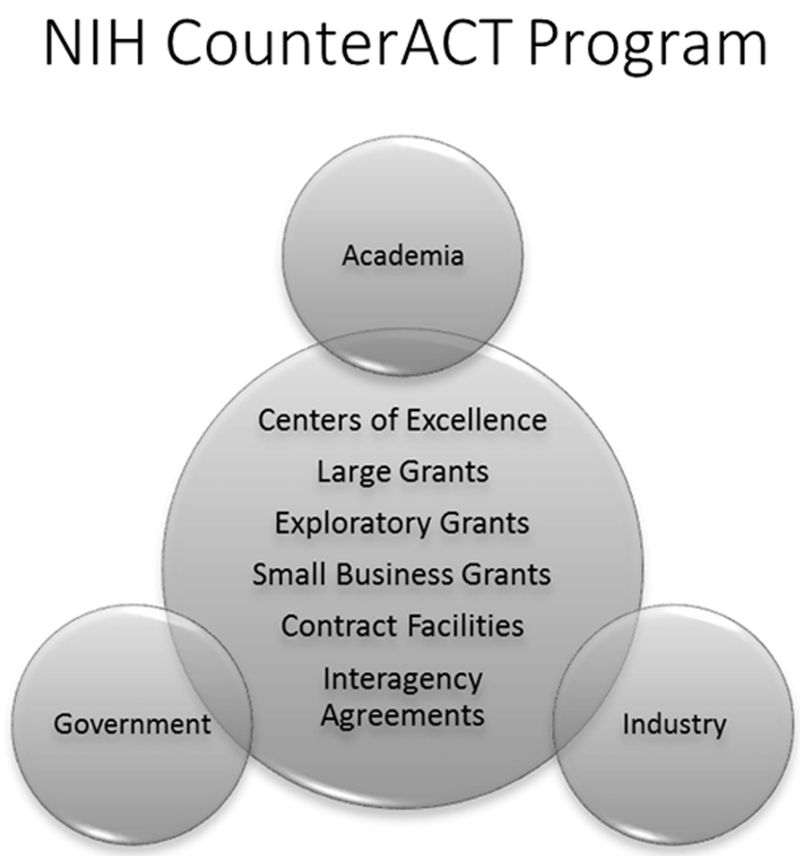

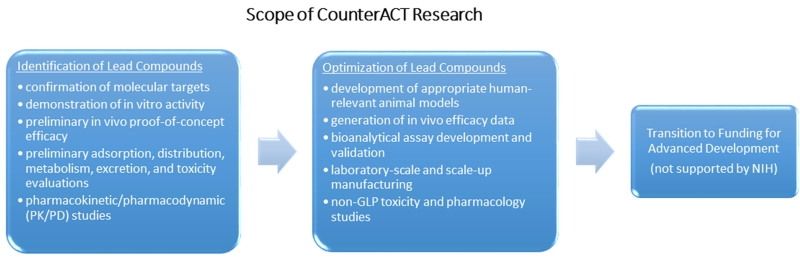

The NIH CounterACT Program network includes investigators supported at Research Centers of Excellence, at other laboratories with individual research projects or small business grants, and at laboratories at the MRICD through interagency agreements (Fig. 2). This network conducts basic, translational, and preclinical research aimed at the discovery and/or identification of better medical countermeasures against chemical threat agents and supports their development toward regulatory approval. Figure 3 describes the scope of research supported in the grants and cooperative agreement programs. A list of current funding opportunities, currently funded projects, and a wealth of information about the NIH CounterACT Program can be found at www.ninds.nih.gov/counteract.

Figure 2.

Components of the NIH CounterACT Program. The program funds research ranging from small exploratory projects to large multi-project Research Centers of Excellence. Many of the projects involve collaborations among scientists from laboratories within academic, government, and industry sectors.

Figure 3.

Scientific scope of NIH CounterACT Program grants and cooperative agreement programs.

To support investigators within the network and for special projects to support the overall PHEMCE effort, the NIH CounterACT program includes several contract resources. For example, the CounterACT Preclinical Development Facility (CPDF) is a resource for conducting preclinical studies, such as safety and pharmacokinetic assessments, that would be needed to support the drug discovery and development processes and ultimate U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/research/counterterrorism/cpdf.pdf). In addition, the CounterACT Efficacy Research Facility (CERF) is a state-of-the-art facility equipped to conduct exploratory and translational research on the efficacy of compounds against the lethal and nonlethal effects of chemical threat agents, using new and established animal models (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/research/counterterrorism/CERF). A unique program that serves a more specific need is the CounterACT Neurotherapeutics Screening (CNS) Program (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/research/counterterrorism/CNS_program.pdf), which includes established animal screening models to identify and accelerate research and development of novel anticonvulsant and neuroprotectant drugs for organophosphorus (OP) chemical threats. These models include OP pesticides as well as CWAs, and the NIH-supported program is a collaboration between the University of Utah and the MRICD. For all three of the abovementioned programs, investigators can submit proposals for a collaboration, and, if accepted through a competitive review, studies can be executed and completed at no cost to the investigator.

Conclusions

Toxic chemicals can pose a threat to human health when released for nefarious purposes, or after accidental exposure. These chemical emergencies can be difficult to manage because of the rapid toxic actions of chemicals and the need for equally rapid medical interventions. Efforts across the U.S. federal government recognize the challenges of responding effectively to chemical emergencies, and the NIH CounterACT Program works in concert with other federal agencies to develop effective medical countermeasures to be used as an important component of the overall preparedness strategy. The NIH CounterACT Program leverages the experience and resources of the DoD and other programs, and engages the NIH research community with relevant experience in diseases that overlap with the clinical manifestations of chemical toxicities. Most estimates of the probability of the deliberate use of chemicals in an attack are high, and accidental releases occur daily. It is therefore a significant burden of illness that is being addressed by efforts to develop better therapeutics for the harmful effects of toxic chemicals. The outlook for discovery and development of these therapeutics is promising, and the goal of enhancing the nation’s medical response capability for chemical emergencies is being advanced every day by dedicated scientists and clinicians.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bajgar J, Fusek J, Kassa J, et al. “Global IMpact of Chemical Warefare Agents used before and after 1945”. In: Gupta RC, editor. Toxicology of CHemical Warfare Agents. Academic Press; London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haines DD, Fox SC. Acute and Long-Term Impact of Chemical Weapons: Lessons from the Iran-Iraq War. Forensic Sci Rev. 2014;26:97–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hakeem O, Jabri S. Adverse birth outcomes in women exposed to Syrian chemical attack. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e196. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosman Y, Eisenkraft A, Milk N, et al. Lessons learned from the Syrian sarin attack: evaluation of a clinical syndrome through social media. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:644–648. doi: 10.7326/M13-2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanagisawa N, Morita H, Nakajima T. Sarin experiences in Japan: acute toxicity and long-term effects. J Neurol Sci. 2006;249:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamasue H, Abe O, Kasai K, et al. Human brain structural change related to acute single exposure to sarin. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:37–46. doi: 10.1002/ana.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murata K, Araki S, Yokoyama K, et al. Asymptomatic sequelae to acute sarin poisoning in the central and autonomic nervous system 6 months after the Tokyo subway attack. J Neurol. 1997;244:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s004150050153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchfiel JL, Duffy FH. Organophosphate neurotoxicity: chronic effects of sarin on the electroencephalogram of monkey and man. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1982;4:767–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassa J, Pecka M, Tichy M, et al. Toxic effects of sarin in rats at three months following single or repeated low-level inhalation exposure. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;88:209–212. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]