Abstract

Five experiments tested implications of the idea that instrumental (operant) extinction involves learning to inhibit the learned response. All experiments used a discriminated operant procedure in which rats were reinforced for lever pressing or chain pulling in the presence of a discriminative stimulus (S), but not in its absence. In Experiment 1, extinction of the response (R) in the presence of S weakened responding in S, but equivalent nonreinforced exposure to S (without the opportunity to make R) did not. Experiment 2 replicated that result and found that extinction of R had no effect on a different R that had also been reinforced in the stimulus. In Experiments 3 and 4, rats first learned to perform several different stimulus and response combinations (S1R1, S2R1, S3R2, and S4R2). Extinction of a response in one stimulus (i.e., S1R1) transferred and weakened the same response, but not a different response, when it was tested in another stimulus (i.e., S2R1 but not S3R2). In Experiment 5, extinction still transferred between S1 and S2 when the stimuli set the occasion for R's association with different types of food pellets. The results confirm the importance of response inhibition in instrumental extinction: Nonreinforcement of the response in S causes the most effective suppression of responding, and response suppression is specific to the response but transfers and influences performance of the same response when it is occasioned by other stimuli. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Extinction, Response Inhibition, Transfer, Instrumental Learning, Operant Conditioning

Extinction in instrumental learning has come under increasing investigation recently. Some of that research has established that instrumental extinction learning, like Pavlovian extinction learning, is relatively specific to the context in which it is learned; when the context is changed after extinction, instrumental responding can be renewed (e.g., Bouton, Todd, Vurbic, & Winterbauer, 2011; Crombag & Shaham, 2002; Nakajima, Tanaka, Urushihara, & Imada, 2000; Todd, 2013). Such renewal also occurs in a discriminated operant setting in which the response (R) is occasioned by a discriminative stimulus (S) (e.g., Todd, Vurbic, & Bouton, 2014; Vurbic, Gold, & Bouton, 2011).

The present experiments were designed to further analyze what is learned during the extinction of a discriminated operant response. Previous research has produced evidence of several possible connections between the response (R), stimulus (S), and reinforcing outcome (O), including R-O, S-O, S-R, and S-(R-O) associations (e.g., Colwill, 1994; Colwill & Rescorla, 1986). In principle, extinction of a discriminated operant response could influence any of these products of learning. However, extinction of a discriminated operant response does not eliminate S-O associations. For example, in experiments using reinforcer devaluation and Pavlovian-instrumental transfer techniques, Rescorla (e.g., 1992a, 1993) found evidence consistent with the idea that the S-O association can survive extinction largely intact (but see Gamez & Rosas, 2005, for contrasting results with humans). Other experiments using these techniques have established that the R-O association may also be preserved through extinction (e.g., Rescorla, 1991, 1992b, 1993).

Rescorla therefore went on to consider the possibility that the animal learns an inhibitory association between S and R during extinction (1993, 1997; see also Colwill, 1991). Confirmation took the form of several experiments in which two instrumental responses were trained and then extinguished in the presence of different stimuli. When each response was then tested in the presence of the other stimulus (with which it had not been extinguished), some response recovery was observed (Rescorla, 1993). Rescorla emphasized a role for an inhibitory S-R association, but also noted that the results were equally consistent with the more hierarchical possibility that S could have developed an inhibitory association with R-O (see also Bouton, 2004; Todd, 2013). We would add that, although Rescorla (1993) demonstrated that R was less suppressed in an S that differed from the S in which it had been extinguished, he did not test whether there was any transfer of response inhibition across stimuli with shared responses. Moreover, although R recovered when it was tested in a different S, its level was still substantially lower than it had been before extinction. Thus, the animal might have also learned a more general tendency to inhibit the instrumental response that goes beyond the specific presence of the extinction-associated discriminative stimulus.

Relevant results have also been reported from our own laboratory. First, we found that extinction exposures to Context A alone have little impact on the ABA renewal effect (Bouton et al., 2011). This seems consistent with results reviewed by Conklin and Tiffany (2002), who suggested that exposure to drug-associated cues alone were not effective in reducing relapse in humans. We suggested that ABA renewal might result in part from Context A being part of either an S-(R-O) relation (e.g., Trask & Bouton, 2014) or an S-R association (e.g., Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a). Todd (2013) went on to find that extinction of one R in a context had no impact on renewal of another response when it was tested in that same context. He noted that some transfer would have been expected if the context were acting as an occasion setter (S-(R-O)), thus implicating, perhaps, an inhibitory association between the context and the response. Todd et al. (2014) then found that, in a discriminated operant setting, extinction of an R (with one S) also reduced renewal of the same R (occasioned by a different S) when the tested SR combination had been extinguished in a separate context. However, extinction of that R had less effect on a different R (also occasioned by a different S). These results confirmed that inhibition of a specific response was learned in extinction. Although that inhibition was relatively specific to its extinction context, the inhibition might in fact transfer to some extent to other Ss tested in the same context.

The purpose of the present experiments was to extend this analysis. We began by asking whether it was necessary to make the response during extinction in order for discriminative extinction to occur. Although the mechanism underlying the learning of response inhibition is not fully understood, it seems reasonable to expect that the animal must emit R to learn to inhibit it: Rescorla (1997) found that the amount of response inhibition learned in instrumental extinction (when responding was permitted in extinction) depended on the level of responding that occurred. In Experiment 1, we therefore compared the impact on discriminative responding of either Pavlovian extinction exposure to the S alone, without the response, or with exposure to the S and the opportunity to make R combined. Although Pearce and Hall (1979) reported that extinction exposure to the context after simple operant training can be sufficient to weaken an operant response, the possible role of response inhibition in extinction suggests that an opportunity to emit R (and learn to inhibit it) during extinction would have a greater impact. The present Experiment 1 suggested that the opportunity to make the response can be essential for operant extinction. Experiment 2 replicated that effect and asked whether the effects of extinction of an R were specific to that R and did not influence a second R that had been separately trained in the same S. Experiments 3 and 4 then asked whether extinguishing the response in the presence of one S transferred to the same response in the presence of other Ss. And Experiment 5 then tested whether response inhibition learned in extinction might transfer to another stimulus that signaled that the response was associated with a different reinforcing outcome. The results consistently suggest that extinction of a discriminated operant involves learning to inhibit the response, and that response inhibition transfers and affects performance of the response in the presence of other discriminative stimuli.

Experiment 1

The design of the first experiment is shown in Figure 1. Three groups of rats were reinforced for lever pressing in the presence of, but not in the absence of, a discriminative stimulus (S). The groups then received different treatments in an extinction phase. Group SR received extinction of lever pressing during a series of presentations of S. Group S received equivalent nonreinforced exposure to the S, but had no opportunity to make the response. A final group, Group Exposure, was merely exposed to the apparatus with neither S nor R available. All animals were then tested (in extinction) for lever pressing in the presence and absence of the S. We hypothesized that to learn to suppress or inhibit the response, the rat would need to make the response in extinction; that is, a response inhibition mechanism predicts that the most effective extinction to occur in Group SR. However, we were also interested in whether Pavlovian exposure to S would weaken responding. Some effect of extinguishing S alone is implied by two-process theories (e.g., Rescorla & Solomon, 1967; Trapold & Overmier, 1972), which emphasize motivation or mediation by the S-O association. To our knowledge, though, the effectiveness of the extinction treatments given to Groups S and SR have never been compared.

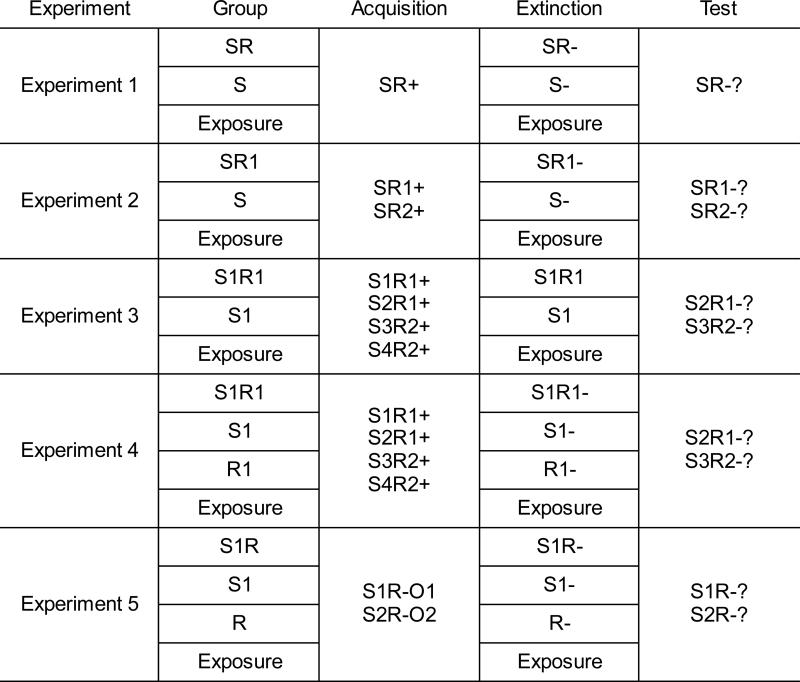

Figure 1.

Designs of Experiments 1 – 5. + signifies reinforced trials; - signifies extinction trials. See text for more explanation.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 24 female Wistar rats purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constance, Quebec). They were between 75 and 90 days old at the start of the experiment and were individually housed in suspended wire mesh cages in a room maintained on a 16:8-h light:dark cycle. The experiment took place on consecutive days during the light period of the cycle. The rats were food-deprived to 80% of their baseline body weight throughout the experiment.

Apparatus

Two sets of four counterbalanced conditioning chambers housed in separate rooms of the laboratory were used. The two sets of chambers were designed to serve as different contexts, although they were not used in that capacity here. Each chamber was housed in its own sound attenuation chamber. All boxes were of the same design (Med Associates model: ENV-008-VP). They measured 30.5 cm × 24.1 × 21.0 cm (l × w × h). In one set of boxes, the sidewalls and ceiling were made of clear acrylic plastic, while the front and rear walls were made of brushed aluminum. The floor was made of stainless steel grids (0.48 cm diameter) staggered such that odd- and even-numbered grids were mounted in two separate planes, one 0.5 cm above the other. A recessed 5.1 cm × 5.1 cm food cup was centered in the front wall approximately 2.5 above the level of the floor. A retractable lever (Med Associates model: ENV-112CM) was positioned 3.2 cm to the left of the food cup. It was 4.8 cm long, was positioned 6.2 cm above the grid floor, and protruded 1.9 cm when extended. A 28-V panel light (2.5 cm in diameter) was attached to the wall 10.8 cm above the floor and 6.4 cm both to the left and right of the food cup. The chambers were illuminated by one 7.5-W incandescent bulb mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber, approximately 34.9 cm from the grid floor at the front wall of the chamber. Ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dB.

The second set of boxes was of the same design, but had the following unique features. In each box, one sidewall had black diagonal stripes, 3.8 cm wide and 3.8 cm apart. The ceiling had similarly spaced stripes oriented in the same direction. The grids of the floor were mounted on the same plane and were spaced 1.6 cm apart (center-to-center). The chambers were illuminated by one 7.5-W incandescent bulb mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber, near the back wall of the chamber.

The reinforcer was a 45-mg grain-based rodent food pellet (TestDiet, Richmond, IN, USA). Four different 30-s Ss were utilized in order to make the method as similar as possible to the methods to be used in Experiments 3 and 4. There were two auditory stimuli: a 3000-Hz tone (80 dB) delivered through a 7.6-cm speaker mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber and a 70-dB intermittent white noise that pulsed with a 4-Hz frequency (i.e., “click”) delivered through the speaker mounted to the back wall of the sound attenuation chamber. There were also two visual stimuli: continuous illumination of the panel light behind the lever or the same light flashing at a 2 Hz frequency (i.e., 0.4 s on, alternated with 0.1 s off).

Procedure

Magazine training

On the first day of the experiment, all rats received a single 30-min session of magazine training in the conditioning chambers. In this session, food pellets were delivered freely on a random time 30-s (RT 30-s) schedule resulting in approximately 60 pellets being delivered. The schedule delivered a pellet in any given second with a probability of 1/30. Neither the stimuli nor the response manipulanda were present during this training.

Response training

Approximately 1.5 hrs following magazine training, the rats received a 30-min session during which lever pressing was reinforced on a variable interval (VI) 30-s schedule. As is typical with this method, the animals learned to respond without any shaping by hand.

Acquisition

Over the next seven days, the rats received two daily 32.5-min sessions in which lever pressing was only reinforced during 30-s presentations of a discriminative stimulus. Two rats in each of three groups received discrimination training with the tone, click, continuous panel light, or flashing panel light. During each session, the rats were given 16 S presentations; the response was reinforced on the VI 30-s schedule during S, but not during the intervals between S presentations (the intertrial interval, or ITI). Discriminative responding was encouraged by increasing the ITI over the first three sessions of training. During the first session, the ITI was 30 s. During the second session, the ITI was variable and increased to 60 s (range: 30-90 s), and during the third and all subsequent sessions the average ITI was 90 s (range: 30-120 s).

Extinction

On the day after the final acquisition day, the three groups (n = 8) received different extinction treatments in each of the next four sessions. In each session, rats in Group SR received sixteen 30-s S presentations with the lever manipulandum available in the chamber. Lever-pressing was never reinforced. Group S also received sixteen 30-s (nonreinforced) S presentations, but the lever was retracted. For both groups, the mean ITI continued to be 90 s. Rats in Group Exposure were placed in the chamber for the same amount of time as the other two groups, but no Ss were presented and the lever was not available. No reinforcers were delivered to any group during this phase.

Test

On the next day, all rats were tested for lever pressing during S. There were eight presentations of S (with the usual mean ITI of 90 s) with the lever available in the chamber. No pellets were delivered. A 180-s delay was imposed before the first S presentation to reduce any pre-S responding differences that may have resulted from the absence of the lever manipulandum during extinction for Groups S and Exposure.

Data analysis

The computer recorded the number of responses made during each 30-s presentation of S as well as during the 30-s period just prior to the S (the pre -S period). Responding during both of these periods was of interest, and both are reported here. We analyzed both with analyses of variance (ANOVA) using a rejection criterion of p < .05. Effect size was estimated by ηp2.

Results

During the first phase of the experiment, the rats learned to respond and confine their responding to the S. In extinction, Group SR decreased its responding in S. During the test, only animals in Group SR showed a reduction in discriminative responding.

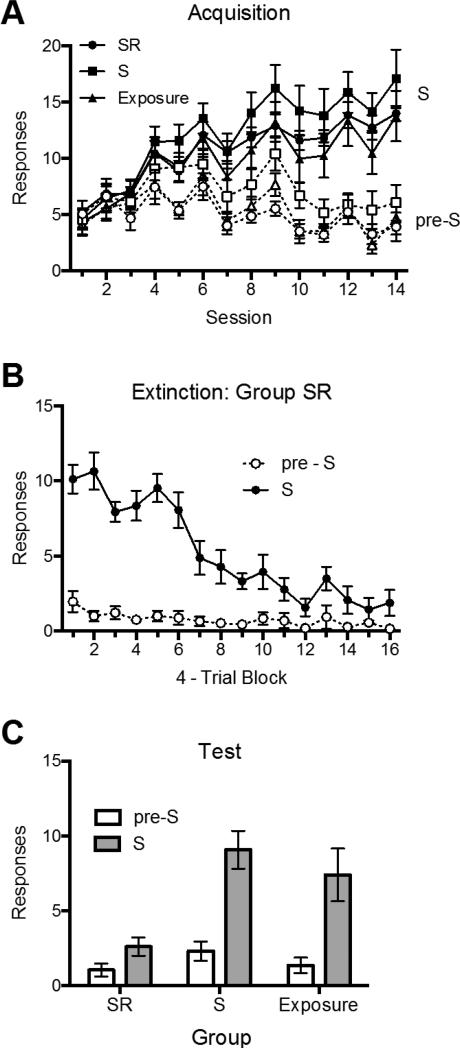

Acquisition

As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, the rats increased their discriminated responding over the 14 acquisition sessions. This was confirmed by a 3 (Group) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 14 (Session) ANOVA which found both a main effect of session, F (13, 273) = 16.68, MSE = 9.26, p < .001, ηp2 = .44, 95% CI [.33, .49], and stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 82.10, MSE = 53.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .80, 95% CI [.58, .87], as well as a significant interaction between the two, F (13, 273) = 35.44, MSE = 3.70, p < .001, ηp2 = .63, 95% CI [.54, .66]. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.60.

Figure 2.

Mean number of responses (+ SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during acquisition (Panel A), extinction for Group SR (Panel B), and test (Panel C) in Experiment 1.

Extinction

As shown in Panel B of Figure 2, animals in Group SR decreased responding during the extinction phase. The decrease was confirmed by a 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 16 (4-Trial Block) ANOVA, which found main effects of session, F (15, 105) = 15.94, MSE = 3.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .70, 95% CI [.55, .73], and stimulus period, F (1, 7) = 58.68, MSE = 22.20, p < .001, ηp2 = .89, 95% CI [.49, .94], as well as an interaction between the two, F (15, 105) = 12.01, MSE = 2.90, p < .001, ηp2 = .63, 95% CI [.46, .67].

Test

The test results are summarized in Panel C of Figure 2, which depicts the mean responding over all eight test trials. The figure suggests that Group SR responded less than Group S and Group Exposure during the S, but not pre-S, periods. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) ANOVA found a significant main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 40.16, MSE = 6.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .66, 95% CI [.36, .78], a main effect of group, F (2, 21) = 6.92, MSE = 8.95, p < .01, ηp2 = .40, 95% CI [.05, .59], and a stimulus period by group interaction, F (2, 21) = 4.64, MSE = 6.86, p < .05, ηp2 = .31, 95% CI [.004, .52]. Planned comparisons revealed that during S, Group SR was suppressed relative to Group S (p < .01) and Group Exposure (p < .05). Groups S and Exposure did not differ (p > .05). In contrast, no group differences were evident during the pre-S period (ps > .05). Additional comparisons showed that while Group S, F (1, 21) = 26.69, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.23, .72], and Group Exposure, F (1, 21) = 21.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .50, 95% CI [.17, .68], showed elevated responding during S relative to the pre-S periods, Group SR did not, F = 1.42, p = .25. Thus, performance of the response during extinction eliminated stimulus control of the response.

Discussion

Consistent with a role for response inhibition, the opportunity to make the response in extinction caused the most effective extinction of a discriminated operant response. Pavlovian exposure to S without the opportunity to make the response (Group S) did not demonstrably reduce responding relative to a group that was exposed to the conditioning chamber alone (Group Exposure). That result suggests that in this experimental preparation, manipulation of the strength of the Pavlovian S-O association alone does not have a major influence on the strength of instrumental responding

One issue that arises is whether the superior transfer of extinction from extinction to testing in Group SR was due to the fact that the response manipulandum (the lever) was present in both phases. The fact that the lever was only present during testing, but not during extinction, in Group S could have reduced generalization and allowed some renewal of responding in the test. It is difficult, if not impossible, to rule out a role for the stimulus properties of the lever. However, it is worth noting that any response recovery brought about by the return of the lever returned responding to its pre-extinction level (i.e., the same level as that in a nonextinguished control). In our hands, the renewal effect in operant learning has never been that complete. In addition, recent experiments with the extinction of heterogeneous instrumental chains have revealed little evidence that the presence/absence of a second response manipulandum causes generalization decrement with a target response (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015b, c).

Experiment 2

The second experiment tested a second implication of the response inhibition hypothesis. If the animal learns to inhibit the response in extinction, then the effect of extinction should be specific to the response that is extinguished. The design of the experiment is shown in Figure 1. All rats first learned to make two responses (R1 and R2, counterbalanced as lever press and chain pull) in the presence of a stimulus (S). Then, in extinction, Group SR1 was allowed to make R1 without reinforcement in S. Group S had the same exposures to S without the opportunity to emit R1, and Group Exposure was again merely introduced to the chamber. In a final test, R1 and R2 were both tested with S. A response inhibition mechanism predicts that extinction of SR1 should suppress SR1, but not SR2. Including Group S further allowed us to replicate Experiment 1's finding that mere exposure to S does not weaken responding (in this case, either R1 or R2).

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

The subjects were 24 naïve female Wistar rats from the same supplier, housed and maintained as before. They were again 75-90 days old at the start of the experiment, and were food-deprived to 80% of their initial body weights throughout.

The apparatus was also the same, except that a chain-pull manipulandum was also used. The chain (Med Associates model ENV-111C) was suspended from a microswitch mounted on top (outside) of the ceiling panel of each operant chamber. The chain hung 1.9 cm from the front wall, 3 cm to the right of the food cup, and 6.2 cm above the grid floor. The lever and chain were positioned symmetrically on opposite sides of the food cup. The reinforcer was the same grain-based food pellet as in Experiment 1. Since no differences were observed depending on S type in Experiment 1, the tone served as S for all rats in this experiment.

Procedure

Magazine training

Magazine training proceeded as in Experiment 1.

R1 and R2 training

On the same day as magazine training, all rats received two additional 30-min training sessions, one with each response (R1 and R2, counterbalanced as lever press and chain pull). Half the rats received training with R1 first and half received R2 first. Only one response was available in any session. During each session, responding was reinforced on a VI 30-s schedule. No hand shaping was necessary.

Acquisition

On each of the next 12 days, all rats received two 32.5-min discrimination training sessions, one for each stimulus/response combination (SR1 and SR2). As before, each session contained 16 30-s presentations of S in which the available response was reinforced on a VI 30-s schedule; responses were not reinforced at any other time. As before, the ITI was 30 s on Day 1, and averaged 60 s on Day 2 and 90 s on Days 3 through 12. Sessions were double alternated such that on odd days, SR1 was trained first and on even days SR2 was trained first.

Extinction

The rats were then divided into three groups (n = 8) in a way that preserved response counterbalancing. On each of the next two days, Group SR1 received extinction of R1 with S using the procedure used in Group SR in Experiment 1. Group S received simple unreinforced tone presentations without being able to perform either response (the response manipulanda were removed). For both groups, there were 16 presentations of S with a variable ITI of 90 s. Group Exposure was placed in the chamber for an equal amount of time (32.5 min); no stimuli or reinforcers were delivered. There were two daily extinction sessions.

Test

On the final day, each rat received two 10-min test sessions that each contained four extinction trials. Sessions were separated by approximately 30 min. In one session, the tone was presented with R1 available, and in the other, the tone was presented with R2 available. The ITI was variable with a mean of 90 s. As in Experiment 1, the sessions started with a 180-s delay before any presentation of S. Half the rats in each group were first tested with SR1 and half were first tested with SR2.

Results

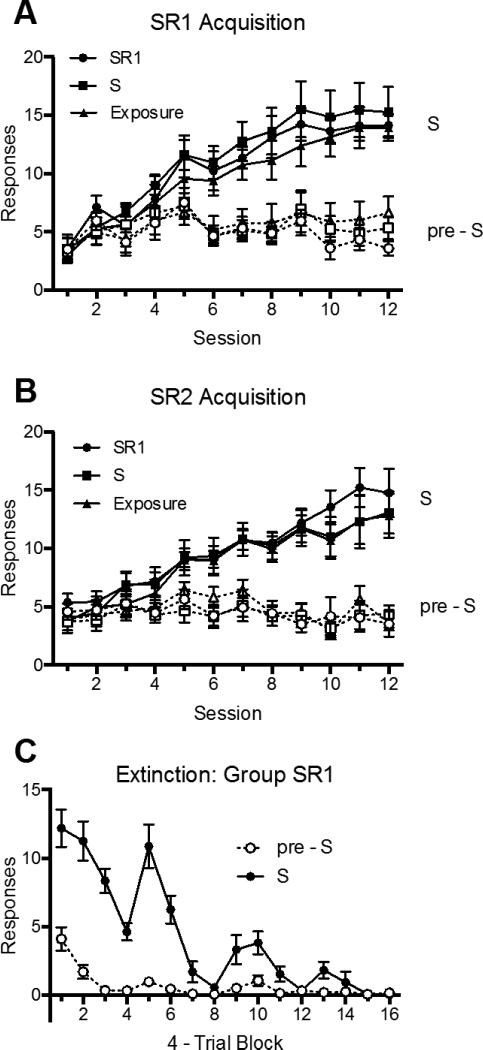

Acquisition

The acquisition of SR1 and SR2 are shown in Panels A and B of Figure 3. A 2 (Response: R1 vs. R2) × 2 (Stimulus Period: On vs. Off) × 12 (Session) × 3 (Group) ANOVA revealed a main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 213.85, MSE = 33.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .91, 95% CI [.81, .94], a nonsignificant main effect of response, F (1, 21) = 3.45, MSE = 76.58, p = .08, ηp2 = .14, 95% CI [.00, .40], and a main effect of session, F (11, 231) = 26.38, MSE = 12.00, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.45, .60]. There was no main effect of group, F < 1. There was both a significant response by session interaction, F (11, 231) = 2.74, MSE = 7.35, p < .01, ηp2 = .11, 95% CI [.02, .16], and a significant stimulus by session interaction, F (11, 231) = 115.61, p < .001, ηp2 = .85, 95% CI [.81, .86]. No other interactions were significant, largest F = 1.84.

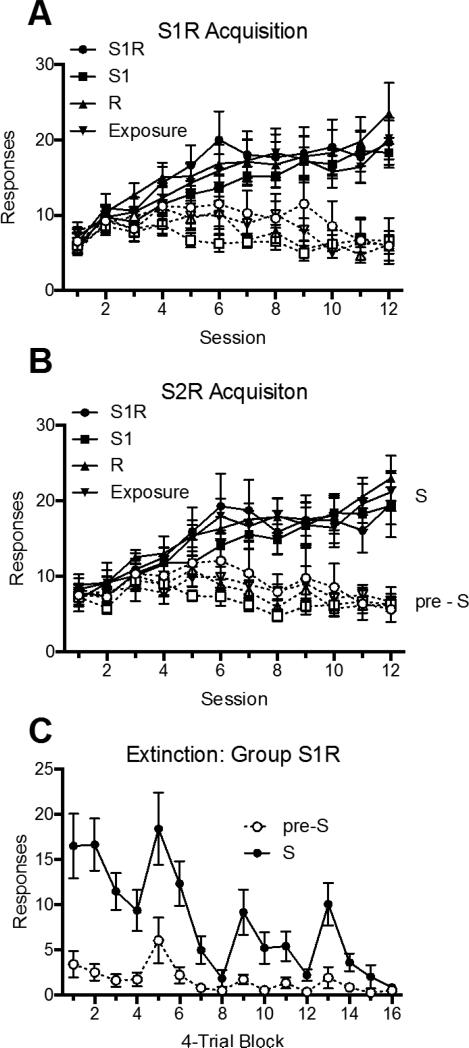

Figure 3.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during SR1 acquisition (Panel A), SR2 acquisition (Panel B), and extinction for Group SR1 (Panel C) in Experiment 2.

Extinction

The results during the extinction phase (Group SR1) are shown in Panel C of Figure 3. A 2 (Stimulus Period: On vs. Off) × 16 (4-trial block) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 7) = 88.65, MSE = 9.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .93, 95% CI [.61, .96], of trial block, F (15, 105) = 29.87, MSE = 3.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .81, 95% CI [.71, .83], and a significant interaction between the two, F (15, 105) = 26.37, MSE = 1.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .79, 95% CI [.68, .81].

Test

The results of the test are summarized in Figure 4. A 2 (Response: R1 vs. R2) × 2 (Stimulus Period: On vs. Off) × 3 (Group) ANOVA revealed a main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 262.96, MSE = 4.03, p <.001, ηp2 = .93, 95% CI [.84, .95], and group, F (2, 21) = 7.45, MSE = 25.84, p < .01, ηp2 = .42, 95% CI [.07, .60]. There was also a response by group interaction, F (2, 21) = 5.18, MSE = 19.27, p < .05, ηp2 = .33, 95% CI [.02, .53], a stimulus period by group interaction, F (2, 21) = 9.84, MSE = 4.03, p = .001, ηp2 = .48, 95% CI [.13, .65], and a near-significant response by stimulus period interaction, F (1, 21) = 4.12, MSE = 7.10, p = .06, ηp2 = .16, 95% CI [.00, .42]. No other effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.97, MSE = 7.10, p = .16.

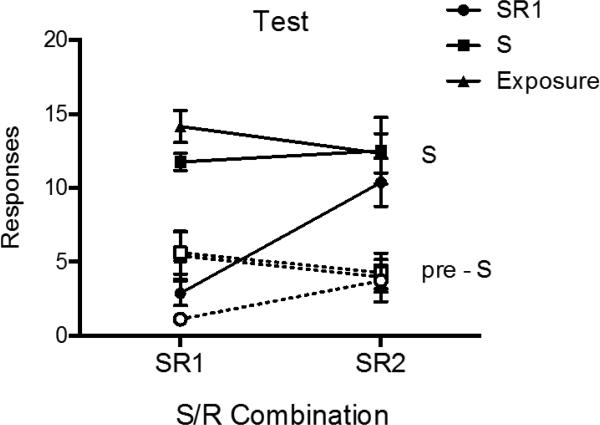

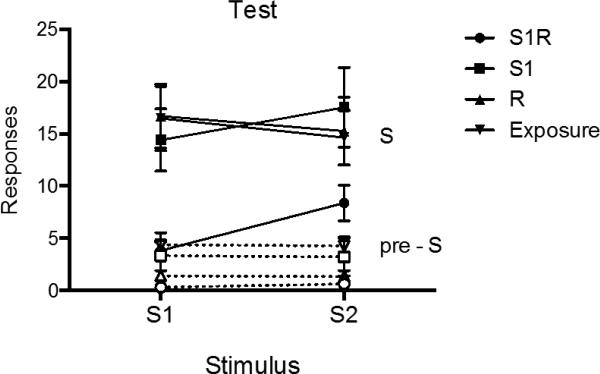

Figure 4.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during the SR1 and SR2 tests of Experiment 2.

Pairwise comparisons during the SR1 test confirmed that Group SR1 was suppressed relative to Group S (p < .001) and Group Exposure (p < .001) during S; Groups S and Exposure did not differ from each other (p > .05). The same was true in the pre-S period, where Group SR1 also responded less that Groups S and Exposure (ps < .05), which did not differ (p > .05). In contrast, during the SR2 test, there were no differences between groups during either the S or pre-S periods (smallest p = .41).

Discussion

The results replicated Experiment 1's finding that making the response in extinction (Group SR1) produced greater suppression of R1 than did simple Pavlovian exposure to S (Group S). As in Experiment 1, there was no detectable effect of extinction of S relative to the control (Group Exposure). However, the new finding is that extinction of R1 in S led to a specific suppression of R1; there was no evidence that a separate response, R2, was suppressed at all. Thus, consistent with the role of response inhibition, extinction of R1 led to a very specific suppression of the R1 response. In this experiment, R1 suppression was evident in both the S and pre-S periods. Response suppression in these periods is dissociated in Experiment 4.

Experiment 3

The purpose of the third experiment was to ask whether response inhibition produced in extinction can transfer and influence the response when it is occasioned by a different discriminative stimulus. As noted in the Introduction, Rescorla (1993) presented evidence suggesting that response inhibition might be at least partly specific to the S with which the response is extinguished. However, he did not run controls that allowed him to ask whether there was any transfer of response inhibition across Ss. Todd et al. (2014) found such evidence in the sense that renewal of an extinguished S1R1 combination was reduced if the same response had previously been extinguished with another S (i.e, S2R1) in the test context. Extinction of a different response (e.g., S3R2) was not as effective.

The design of Experiment 3 is summarized in Figure 1. All rats initially learned to make one response (R1, again counterbalanced as lever press or chain pull) in the presence of S1 and S2, and the other response (R2) in the presence of S3 and S4. During the extinction phase that followed, Group S1R1 received extinction of the S1R1 combination, whereas Groups S1 and Exposure received equivalent nonreinforced exposure to S1, or the chamber only, with the R1 manipulandum removed. In the final test, all rats were tested for both R1 and R2 combined with transfer stimuli that had not been involved in extinction (S2 and S3). The stimuli were balanced so that the stimuli tested were both of the modality opposite to that of S1. If discriminated operant extinction involves the animal learning to inhibit its response, we might observe a suppression of R1 responding in S2 but no suppression of R2 responding in S3 in Group S1R1. No such suppression was expected in the other groups.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

The rats were 24 naïve female Wistar rats of the same age and from the same supplier as before. Their housing and maintenance, as well as the apparatus, were also the same. The experiment utilized the lever and chain used in Experiment 2 and the discriminative stimuli (tone, click, flash, and light) used in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Magazine training

Magazine training proceeded as in the previous experiments.

R1 and R2 training

On the next day, all rats received a 30-min training session with each response (i.e., lever press and chain pull); only one response manipulandum was available in any session. During each session, responding on the available manipulandum was reinforced on a VI 30-s schedule. No hand shaping was necessary.

Acquisition

On each of the next 12 days, all rats received four discrimination 32.5-min training sessions, one session for each stimulus-response combination (S1R1, S2R1, S3R2 and S4R2). In any session, the rats received 16 trials of a single stimulus-response combination in which the only available response was reinforced during 30-s presentations of one S and not reinforced in its absence. R1 was lever pressing for half the animals and chain pulling for the other half. The stimuli were fully counterbalanced so that the tone, click, steady light and flashing light were each S1, S2, S3, and S4 for 25% of the rats. For any animal, S1 and S4 were always one modality and S2 and S3 were the other (e.g., if S1 and S4 were auditory stimuli, then S2 and S3 were visual). During each S, responding was always reinforced on a VI 30-s schedule.

As before, the ITI was 30 s on Day 1, and averaged 60 s on Day 2 and 90 s on Days 3 through 12. In order to enable the counterbalancing and running of four sessions each day per rat, the rats were run in 4 squads of 6 rats. The stimuli were presented in different orders each day using a latin square design such that animals experienced S1, S2, S3, S4 on Days 1, 5, and 9; S2, S3, S4, S1 on Days 2, 6, and 10; S3, S4, S1, S2 on Days 3, 7, and 11; and S4, S1, S2, S3 on days 4, 8, and 12.

Extinction

The rats were then divided into three groups (n = 8) in a way that preserved the stimulus and response counterbalancing. On each of the next four days, rats in Group S1R1 received extinction of R1 with its S1 using the procedure used in Group SR in Experiment 1. Rats in Group S1 received unreinforced presentations of S1 without being able to perform the response (the response manipulanda were removed). For both groups, there were 16 presentations of S1 with a variable ITI of 90 s. Animals in Group Exposure were merely exposed to the chamber for an equal amount of time. No reinforcers were ever delivered. There was one session per day throughout this phase.

Test

On the final day, each rat received two 10-min test sessions that each contained four extinction trials. Sessions were separated by approximately 75 min. In one session, S2 was presented with R1 available, while in the other session, S3 was presented with R2 available. As noted earlier, S2 and S3 were from the opposite modality as the extinguished S1. As before, the ITI was variable with a mean of 90 s. Also as before, the sessions started with a 180-s delay before any S presentation. Half the rats were tested first with S2R1 and half with S3R2.

Results

All groups acquired discriminated responding with all four SR combinations. During extinction, Group S1R1 gradually suppressed responding during S1. During testing, Group S1R1 was suppressed during the S2R1 test, but not the S3R2 test. No other group showed a similar suppression of responding.

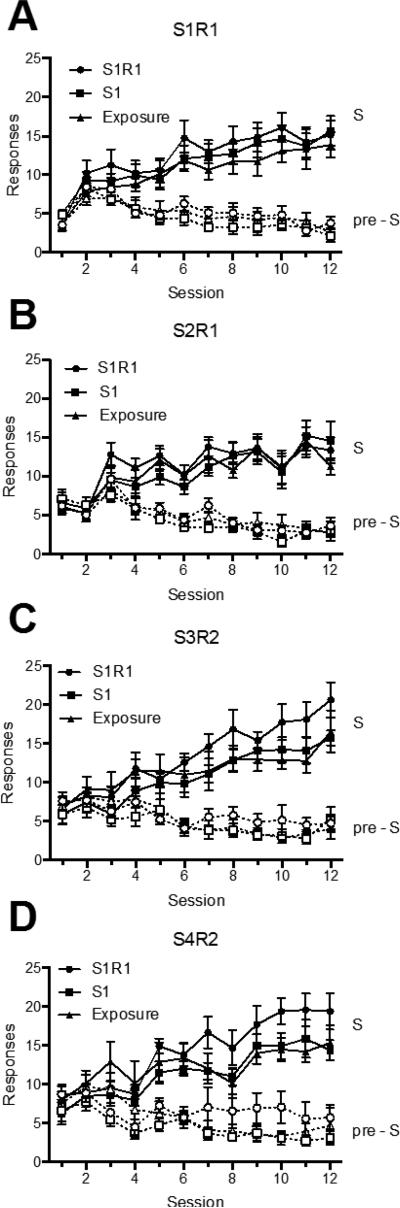

Acquisition

The data from acquisition are presented in Figure 5, which shows S and pre-S responding for S1R1 (Panel A), S2R1 (Panel B), S3R2 (Panel C), and S4R2 (Panel D) over sessions. A 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 4 (S-R Pairing) × 3 (Group) × 12 (Session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F (11, 231) = 8.76, MSE = 17.74, p < .001, ηp2 = .29, 95% CI [.17, .68], a near-significant effect of SR pairing, F (3, 63) = 2.47, MSE = 87.93, p = .07, ηp2 = .11, 95% CI [.00, .23], and a main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 392.41, MSE = 64.29, p < .001, ηp2 = .95, 95% CI [.88, .97]. The ANOVA also revealed a session by S-R pairing interaction, F (33, 693) = 4.57, MSE = 10.03, p < .001, ηp2 = .18, 95% CI [.09, .19], a session by stimulus period (pre-S vs. S) interaction, F (11, 231) = 163.15, MSE = 5.10, p < .001, ηp2 = .89, 95% CI [.85, .90], and a significant three-way interaction, F (33, 693) = 2.76, MSE = 2.89, p < .001, ηp2 = .12, 95% CI [.04, .12]. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.16.

Figure 5.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during acquisition in Experiment 3. Acquisition for the four stimulus/response combinations are shown separately: S1R1 in Panel A, S2R1 in Panel B, S3R2 in Panel C, and S4R2 in Panel D.

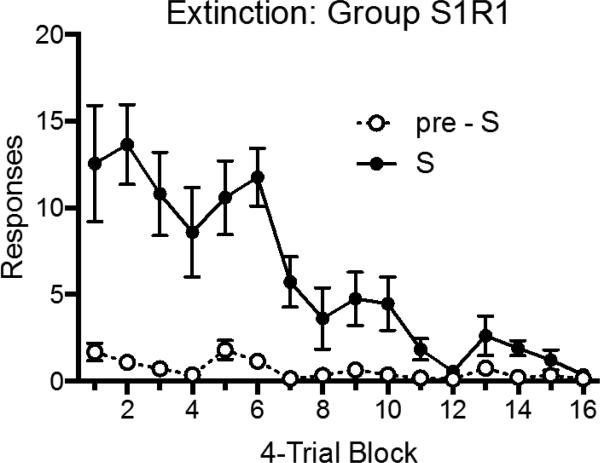

Extinction

The extinction results with Group S1R1 are shown in Figure 6. A 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 16 (4-Trial Block) found significant main effects of block, F (15, 105) = 14.86, MSE = 6.99, p < .001, ηp2 = .68, 95% CI [.52, .71], and stimulus period, F (1, 7) = 17.72, MSE = 101.77, p < .01, ηp2 = .72, 95% CI [.13, .85], as well as an interaction between the two, F (15, 105) = 12.03, MSE = 5.98, p < .001, ηp2 = .63, 95% CI [.46, .67].

Figure 6.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during the extinction treatment given Group S1R1 in Experiment 3.

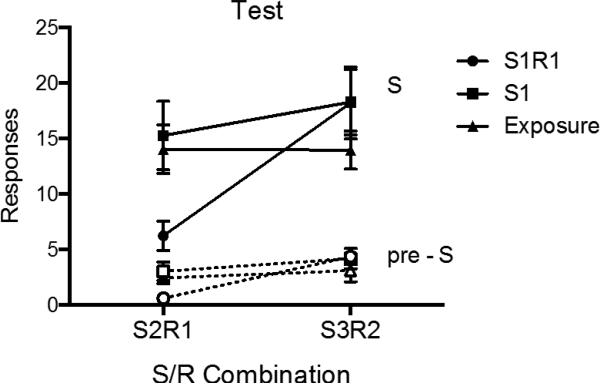

Test

The test results are summarized in Figure 7, which shows mean responding of each group during the S and pre-S periods of the S2R1 and S3R2 tests. A 2 (S-R Pairing) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 4 (Group) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of stimulus period, F (1, 21) = 106.29, MSE = 29.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .84, 95% CI [.66, .89], a main effect of S-R pairing, F (1, 21) = 9.08, MSE = 30.86, p < .01, ηp2 = .30, 95% CI [.03, .53], and a significant group by S-R pairing interaction, F (2, 21) = 4.08, MSE = 30.86, p < .05, ηp2 = .28, 95% CI [.00, .49]. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 2.80, p = .11. Pairwise comparisons analyzing R1 responding during S2 found that Group S1R1 was lower than Group S1 (p < .05) and Group Exposure (p < .05), which did not differ (p > .05). The groups did not differ in S responding during the tests of S3R2 (ps > .05). Similar comparisons conducted on pre-S responding revealed that during the S2R1 test, Group S1R1 responded less than Group S1 (p < .01) and Group Exposure (p < .05), which did not differ (p > .05). No differences were detected in the S3R2 test in pre-S responding (ps > .05). Further comparisons assessed whether there was any stimulus control evident during the S2R1 and S3R2 tests. During the S2R1 test, all groups elevated their responding during S as compared to pre-S periods (Group S1R1: F (1, 21) = 6.45, p < .05, ηp2 = .24, 95% CI [.004, .48], Group S1: F (1, 21) = 30.26, p < .001, ηp2 = .59, 95% CI [.27, .74], Group Exposure: F (1, 21) = 27.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.24, .72]). This was also true during the S3R2 test (Group S1R1: F (1, 21) = 25.42, p < .001, ηp2 = .55, 95% CI [.22, .71], Group S1: F (1, 21) = 26.46, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.23, .72], Group Exposure: F (1, 21) = 15.69, p = .001, ηp2 = .43, 95% CI [.10, .63]).

Figure 7.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods for each group during the transfer test sessions of Experiment 3.

Discussion

The main finding of this experiment was that extinction of R1 in S1 strongly reduced the same response when it was occasioned by a different S (S2). This treatment had no apparent impact on a different response (i.e., S3R2). Moreover, no such effect was produced when S1 received simple Pavlovian extinction. The results continue to point to the importance of making the response in order to produce effective discriminated operant extinction; suppressed responding in S2R1 required direct extinction of the response. Interestingly, although extinction of R1 in S1 transferred to S2R1, S2 was still able to elevate R1 responding relative to pre-S periods in Group S1R1. Perhaps consistent with the results reported by Rescorla (1993), transfer of extinction of R1 in S1 to S2 was thus not complete, although such a conclusion can only be accepted with caution here, because there was no comparison group that received direct extinction of S2R1. However, the main point is that the present results clearly establish that substantial transfer of R1 extinction does in fact occur across discriminative stimuli.

It is worth noting that S1R1 extinction suppressed R1 in the absence of S1, that is, in the pre-S period (see also Experiment 2). That result is consistent with a role for response inhibition, of course, and it is worth noting that R1 received extinction in both S1 and in the absence of S1 during the extinction phase. But the finding also raises the possibility that the effects of R1 inhibition in S2 only reflected the same general inhibitory effect. The fourth experiment was therefore designed to address this possibility.

Experiment 4

The design of Experiment 4 is summarized in Figure 1. Three of the groups (S1R1, S1, and Exposure) received the same treatments as the groups with the same names in Experiment 3, and thus assessed the replicability of that experiment's findings. However, a fourth group (Group R1) received simple extinction exposure to R1, without S1, in the extinction phase. This treatment was expected to reduce R1 responding in the pre-S period during testing. The question was whether it would also reduce responding in S2 (S2R1), and thus, whether inhibition of R1 in the pre-S period could be dissociated from inhibition of R1 responding in S2.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

The subjects were 32 naïve female Wistar rats of the same stock as before. The apparatus, housing, and maintenance conditions were also the same.

Procedure

Magazine training, response shaping, and acquisition proceeded as described in Experiment 3. At the end of acquisition, the rats were divided into four groups (n = 8) in a way that preserved stimulus and response counterbalancing. On each of the next two days, rats in Groups S1R1, S1, and Exposure received the extinction treatments that their namesakes received in Experiment 3. A new group, Group R1, had the R1 manipulandum available in the chamber, but no discriminative stimuli (or reinforcers) were presented. The duration of the extinction sessions was identical to the duration of the acquisition sessions, and there were 16 presentations of S1 with an average ITI of 90 s for groups S1R1 and S1. The rats received two extinction sessions per day during this phase.

On the final day, each rat received two 10-min test sessions following the procedure used in Experiment 3. S2R1 was tested in one session, and S3R2 was tested in the other (sequence counterbalanced). In this experiment, the test sessions were separated by approximately 1 hr.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed as before. One rat was injured during acquisition and had to be euthanized. A second rat failed to acquire discriminated responding during acquisition. Neither animal was included in any statistical analyses. A final rat in Group S1R1 was excluded because its response rate tripled in S from the last day of acquisition to the first test trial and it was consequently a significant outlier during the first trial of the S2R1 test (Z = 2.58) as well as in the first two trials combined (Z = 2.09) (see Field, 2005).

Results

Acquisition and extinction proceeded as reported in Experiment 3. During the final test, while Groups S1R1 and R1 were both suppressed during the pre-S period of the S2R1 test relative to the other groups, only animals in Group S1R1 were suppressed during the S2 stimulus period. No group differences were seen in the S3R2 test.

Acquisition and extinction

Acquisition and extinction proceeded as reported in Experiment 3 (data not shown), and are not reported here for the sake of brevity.

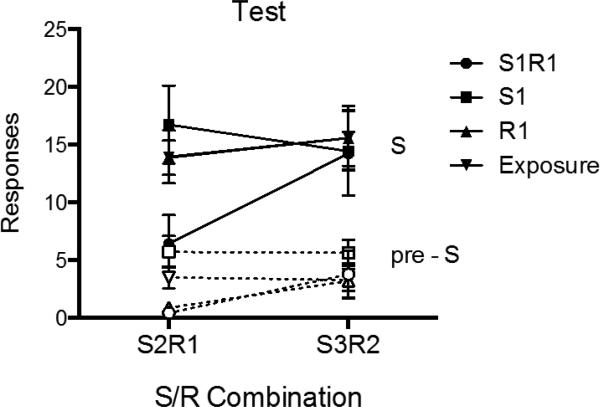

Test

Responding during the final S2R1 and S3R2 tests is summarized in Figure 8. A 2 (S-R Pairing) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 4 (Group) ANOVA conducted over the first two trials of the test yielded a significant effect of stimulus period, F (1, 25) = 156.25, MSE = 20.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .86, 95% CI [.73, .91], and a near-significant effect of S-R pairing, F (1, 25) = 3.44, MSE = 26.54, p = .08, ηp2 = .12, 95% CI [.00, .36]. No other main effects or interactions were reliable, largest F = 2.13, p = .12. Group comparisons of responding during S2R1 found that Group S1R1 was significantly lower than Groups S1 (p < .01), Exposure (p < .05), and R1 (p < .05). The latter three groups did not differ from each other (ps > .05). In contrast, no group differences in S responding were detected during the S3R2 test (ps > .05).

Figure 8.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods for each group during the transfer test sessions of Experiment 3.

Similar comparisons during the pre-S periods revealed that during the S2R1 test, Groups S1R1 and R1 both responded less than Group S1 (ps < .001) and Group Exposure (ps < .05), but did not differ from one another (p > .05). There were no differences in pre-S responding during the S3R2 test (ps > .05).

Additional comparisons again assessed whether S elevated responding during the S2R1 and S3R2 tests. During the S2R1 test, all groups increased responding during the S relative to pre-S periods (S1R1: F (1, 25) = 6.61, p < .05, ηp2 = .21, 95% CI [.01, .44], S1: F (1, 25) = 22.23, p < .001, ηp2 = .47, 95% CI [.17, .65], R1: F (1, 25) = 35.83, p < .001, ηp2 = .59, 95% CI [.30, .73], Exposure: F (1, 25) = 19.71, p < .001, ηp2 = .44, 95% CI [.14, .63]). Thus, although S1R1 extinction again reduced R1 responding in the presence of S2, it did not abolish stimulus control by S2. Not surprisingly, all groups also showed an increase in responding from pre-S to S during the S3R2 test (S1R1: F (1, 25) = 19.82, p < .001, ηp2 = .44, 95% CI [.14, .67], S1: F (1, 25) = 14.06, p = .001, ηp2 = .36, 95% CI [.07, .57], R1: F (1, 25) = 31.89, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.26, .71], Exposure: F (1, 25) = 27.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .52, 95% CI [.22, .68]).

Discussion

The results of this experiment replicated those of Experiment 3: Extinction of R1 in S1, but not simple Pavlovian extinction exposures to S1, suppressed responding of R1 in the presence of a transfer stimulus, S2. And, also consistent with Experiment 3 (see also Experiment 2), extinction of S1R1 suppressed R1 responding in the pre-S period. The new result is that extinction of R1 without S1 (Group R1) was equally effective at suppressing R1 in the pre-S period, but had no discernible inhibitory effect on responding in the presence of S2. Transfer of response inhibition to S2 required specific extinction of R1 in the presence of S1. Stimulus generalization between S1 and S2 is unlikely given that these stimuli were from different sensory modalities. The results may be consistent with results reported by Rescorla (1997), who found that instrumental extinction procedures were most effective when they encouraged more responding in extinction. Because S1 always set the occasion for R1 in extinction, the present Group S1R1 initially made more R1 responses in extinction than did Group R1. That is, Group R1's responding in extinction was no higher than that of Group S1R1 during pre-S periods; the presentation of S in Group S1R1 elevated responding above that baseline (Figure 6.)

Experiment 5

The fifth experiment was designed to further extend the previous experiments by asking whether response inhibition learned in extinction would transfer to a different S when the S set the occasion for the same response being reinforced with a different outcome (O). If the animal learns simple response inhibition in extinction, that inhibition might transfer between Ss, regardless of whether the response was reinforced by different outcomes in the two stimuli.

The design of the experiment is shown in Figure 1. During training, rats learned that lever pressing (R) was reinforced in the presence of two different Ss (S1 and S2). In the presence of S1, R was reinforced with O1; in the presence of S2, R was reinforced with O2. O1 and O2 were provided by grain and sucrose food pellets (counterbalanced). Previous research in this laboratory has found these pellets to be discriminably different (Bouton, Todd, León, Miles, & Epstein, 2013; Bouton & Trask, 2015; Trask & Bouton, 2014; 2015), and they enter into separate associations with different Rs (Trask & Bouton, 2014). The new question was whether extinction of the response in S1 would still transfer to S2 when R had been associated with another outcome in that stimulus.

All rats received training as described above. Then, as in Experiment 4, different groups received extinction of R in the presence of S1, S1 or R alone, or simple exposure to the apparatus. After extinction, all groups were tested for responding (R) in the presence of both S1 and S2. If the animal learns simple response inhibition in extinction, that inhibition should readily transfer from S1 to S2.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

The subjects were 32 naïve female Wistar rats purchased from the usual vendor and housed and maintained as before. The apparatus was also the same. Lever pressing provided the only R, and the tone and continuous light stimuli were counterbalanced as S1 and S2. The reinforcers were a 45-mg grain-based rodent food pellet (as before) and a 45-mg sucrose-based food pellet (5-TUT: 1811251, TestDiet, Richmond, IN, USA). Both pellets were delivered to the same food cup.

Procedure

Magazine training

On the first day of the experiment, all rats received two 30-min magazine training sessions. The first was with one reinforcer (grain-based or sucrose-based food pellet, counterbalanced), and the second was with the other. Half the rats were trained with O1 first and half with O2 first. The interval between sessions was approximately two hrs. In each session, approximately 60 reinforcers were delivered on a random time 30-s (RT 30-s) schedule. The response manipulanda were not present.

Response training

The following day, the rats received two 30-min sessions during which lever pressing was reinforced on a VI 30-s schedule with either O1 or O2. For half the animals, lever pressing was reinforced in the first and second sessions with O1 and then O2, and for the other half the order was reversed. Sessions were again separated by approximately two hrs.

Acquisition

On each of the next 12 days, all rats received two 32.5-min training sessions, one session for each stimulus-response-reinforcer combination (S1: R – O1; S2: R – O2) shown in Figure 1. In each session, there were 16 trials in which S was presented for 30 s and lever pressing was reinforced on the VI 30-s schedule with the corresponding reinforcer. Tone and light were counterbalanced as S1 and S2. As usual, the ITI was 30 s on Day 1, and averaged 60 s on Day 2 and 90 s on Days 3 through 12. Session type was doubly alternated so that S1: R – O1 and S2: R – O2 were the days’ first and second session equally often. That is, on odd-numbered training days, animals received training with S1 then S2, and on even days they received S2 then S1.

Extinction

The rats were then divided into four groups (n = 8) in a way that preserved all counterbalancing. On each of the next two days there were two extinction sessions. In each, Group S1R received 16 presentations of S1 with the lever presses available and not reinforced. Group S1 received 16 unreinforced presentations of S1 without being able to perform the response (the lever was retracted). The ITI for both groups was a variable 90 s. Group R1 received no stimuli, but had the lever available, and Group Exposure received only equivalent exposure to the conditioning chamber (without Ss or lever available). The duration of the extinction sessions was again 30 min.

Test

On the final day, each rat received two 10-min test sessions that each contained 4 extinction trials. Sessions were separated by approximately 75 min. In one session, S1 was presented with the lever available, while in the other session, S2 was presented (still with the lever available). The ITI was again variable with a mean of 90 s. These sessions started with a 180-s delay before any S presentation. Half the rats were tested with S1R first and half were tested with S2R first.

Results

Acquisition and extinction proceeded uneventfully. During testing, Group S1R showed suppressed responding during both the pre-S and S periods of the S1R test, and this transferred to the S2R test.

Acquisition

Acquisition is shown in Panels A and B of Figure 9. A 2 (S-R Pairing) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 4 (Group) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of session, F (11, 308) = 16.58, MSE = 28.42, p < .001, ηp2 = .37, 95% CI [.27, .43], and stimulus period, F (1, 28) = 131.49, MSE = 140.89, p < .001, ηp2 = .82, 95% CI [.67, .88], as well as a significant interaction between the two, F (11, 308) = 78.13, MSE = 8.68, p < .001, ηp2 = .74, 95% CI [.68, .76]. While there was a S-R pairing by session interaction, F (11, 308) = 3.24, MSE = 7.47, p < .001, ηp2 = .10, 95% CI [.02, .14], no other interactions or main effects (including group) were significant, largest F = 1.14.

Figure 9.

Mean number of responses (+ SEM) during the S and pre-S periods during S1R acquisition (Panel A), S2R acquisition (Panel B), and extinction for Group S1R (Panel C) in Experiment 5.

Extinction

Extinction for Group S1R is shown in Panel C of Figure 9. A 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 16 (4-Trial Block) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F (1, 105) = 10.50, MSE = 19.08, p < .001, ηp2 = .09, 95% CI [.01, .20], and stimulus, F (1, 15) = 20.97, MSE = 128.08, p < .01, ηp2 = .58, 95% CI [.19, .75], as well as an interaction between the two, F (15, 105) = 12.59, MSE = 6.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .64, 95% CI [.47, .68].

Test

The results of the test are shown in Figure 10. A 2 (Stimulus: S1 vs. S2) × 2 (Stimulus Period: pre-S vs. S) × 4 (Group) ANOVA revealed a main effect of stimulus period, F (1, 28) = 126.71, MSE = 30.73, p < .001, ηp2 = .82, 95% CI [.66, .88], and of group, F (3, 28) = 3.50, MSE = 88.46, p < .05, ηp2 = .27, 95% CI [.00, .45], as well as a significant stimulus period by group interaction, F (3, 28) = 3.88, MSE = 30.73, p < .05, ηp2 = .29, 95% CI [.01, .47]. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.81. Importantly, the effect of group did not interact with Stimulus, suggesting that the between-group pattern was largely the same in S1 and S2.

Figure 10.

Mean number of responses (± SEM) during the S and pre-S periods for each group during the test sessions of Experiment 5. Responding in S1 and S2 is shown separately.

Additional comparisons revealed that during S1, Group S1R differed from Groups S1 (p < .01), R1 (p < .01), and Exposure (p < .01), which did not differ from each other (smallest p = .55). During S2, Group S1R differed from Group S1 (p < .05), but neither Group R1 (p = .11) nor Group Exposure (p = .15). To increase the power to detect differences, we compared Group S1R with the other groups’ pooled data and found that Group S1R was significantly suppressed, t (30) = 2.23, p < .05, ηp2 = .14, 95% CI [.00, .36]. Groups S1, R, and Exposure did not differ (smallest p = .49).

As usual, responding during the pre-S periods was also analyzed. During the S1 test, Group S1R differed from Groups S1 (p < .05) and Exposure (p < .01), but not Group R1 (p = .42). Group R1 differed from Group Exposure (p < .05), but not Group S1 (p = .15). Groups S1 and Exposure did not differ (p = .44). During the pre-S period of the S2 test, Group S1R differed significantly from Group Exposure (p < .05), but not Group S1 (p = .10) or Group R1 (p = .64). Group R did not differ from either Group S1 (p = .22) or Group Exposure (p = .06). Groups S1 and Exposure did not differ (p = .49).

No within-group differences were detected on pre-S responding between the S1R test and the S2R test, Fs < 1. During S responding, Group S1R showed a tendency to respond less during the S1R test relative to the S2R test, F (1, 28) = 3.82, p = .06, ηp2 = .12, 95% CI [.00, .34]. This trend was not found in any other group, largest F = 1.79.

It is worth noting that all groups showed elevated responding compared with the pre-S baseline during the S2 tests (S1R: F (1, 28) = 9.82, p < .01, ηp2 = .26, 95% CI [.03, .48], S1: F (1, 28) = 33.49, p < .001, ηp2 = .54, 95% CI [.26, .69], R: F (1, 28) = 31.62, p < .001, ηp2 = .53, 95% CI [.25, .68], Exposure: F (1, 28) = 17.49, p < .001, ηp2 = .38, 95% CI [.11, .58]). In contrast, during the S1 test, responding was significantly elevated in Groups S1, R, and Exposure (Fs (1, 28) > 28.99, p < .001, ηp2 = .51, 95% CI [.22, .67]) but not Group S1R, F (1, 28) = 2.90, p = .10.

Discussion

The results indicate that extinction of responding in an S in which R had been paired with one outcome transferred to a second S in which R had been paired with a different outcome. Once again, there was no evidence of a response-suppressing effect of either nonreinforced exposure to S1 (Group S1) or R (Group R) alone. There was some evidence of specificity of S1R extinction on responding to S1; although transfer to S2 was substantial, S2 still facilitated responding even when S1 did not (that is, there was some recovery of the suppressed response when testing occurred with S2). Recall that a similar result was also evident in Experiments 3 and 4, where Group S1R1 still showed elevated responding during S2R1 when R1 had been associated with the same outcome in S1 and S2 (see also Rescorla, 1993). Thus, the present evidence of some modest specificity of suppression to S1R is not unique to having different reinforcing outcomes in S1 and S2. The use of different reinforcers did little to change the amount of transfer observed between S1R1 and S2R1. In a preliminary way, this result suggests that the evidence of response inhibition in the present experiments may reflect direct inhibition of R rather than inhibition of the specific R-O relationship.

General Discussion

The present experiments explored the role of response inhibition in the extinction of discriminated operant behavior. Experiment 1 established that an extinction procedure in which the rat could make the response (R) without reinforcement in the presence of its discriminative stimulus (S) was effective at weakening the response in the stimulus. In contrast, a Pavlovian extinction procedure in which the rat received equal exposure to S without the opportunity to make the response did not weaken the response. Indeed, with the present methods there was no evidence that Pavlovian exposure to S without R had any effect on R. Experiment 2 replicated those results, but found that extinction of R1 in S specifically suppressed R1, and not a different response (R2) that had been reinforced in the same stimulus. In Experiments 3 and 4 then found that extinction of one R in one S (i.e., S1R1) transferred and suppressed responding in a second S that had set the occasion for the same response (S2R1), but had no measurable impact on a different response in the presence of another S (S3R2). There was no such effect when rats received simple Pavlovian exposure to S (Experiments 3 and 4) or an opportunity to experience nonreinforcement of R in the absence of S (Experiment 4 and 5). The latter result is not necessarily surprising, because the animal had already learned during training that R was nonreinforced in the absence of S. However, exposure to R weakened R to a baseline level that was similar to that in the group that had received extinction of S1R1; the fact that the latter group still showed less responding in S2 indicates that the result is not merely due to lowered baseline responding. Finally, the results of Experiment 5 suggest that extinction of R in the presence of S transferred to a second S that had set the occasion for the same R being associated with a different outcome. That result suggests that the transfer of extinction between stimuli might work via suppression of the response, rather than the specific response-outcome relation.

The results provide new evidence that extinction of operant behavior involves learning to inhibit the response. First, in each experiment, the opportunity to make the response without reinforcement was necessary to weaken it. Simple Pavlovian extinction exposure to S without R was never effective. That result fits with other research in this laboratory. We have previously found that Pavlovian extinction exposure to Context A does not reduce the ABA renewal effect in a free operant (nondiscriminated operant) procedure (Bouton et al., 2011). In studies of the extinction of discriminated heterogeneous chains, we have also found that direct extinction of a response, and not extinction exposure to its associated S, weakens other responses in the chain (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015b, 2015c). Second, the present results provided independent evidence of response inhibition in two ways. In the first way, Experiment 2 found that extinction of R1 suppressed R1, but had no effect on a second response (R2) that had been reinforced in the same stimulus. Experiments 3 and 4 further found that such specific response inhibition transferred and inhibited R1 when it was controlled by a second S (Experiments 3 and 4). In those experiments, extinction of S1R1 weakened S2R1 responding, although importantly, it did not affect S3R2. Thus, the inhibition learned in extinction was specific to the response, but not the stimulus. Finally, the results of Experiment 5 suggest that inhibition of a response in one S can transfer to a second S that signaled the response being associated with a different reinforcer. The results of that experiment thus suggested that the inhibition learned in extinction was about the response, and not the response-reinforcer relation. Recall that Todd (2013) also found that extinction of an R had no impact on renewal of a second R (tested in the same context) when the responses had been associated with the same outcome and had received similar acquisition and extinction treatments. Some transfer would have been expected if extinction had involved negative occasion setting of an R – outcome relation (e.g., Holland, 1992). Overall, the results thus implicate a role for simple and direct inhibition of R in operant extinction.

As we noted in the Introduction, previous research by Rescorla (1993) also suggested the role of response inhibition in operant extinction. In several experiments, Rescorla trained two responses and then extinguished them in the presence of different stimuli; responding was renewed to some extent when it was tested in the stimulus in which it had not be extinguished (Rescorla, 1993). The present Experiments 3-5 obtained results in line with Rescorla's observations. There we found that S2 was still able to weakly augment R1 after apparently complete extinction of responding in S1R1 (see especially Experiment 5, where S1R1 and S2R1 were directly compared during testing). However, the experiments also found strong and considerable transfer of response inhibition between the two different discriminative stimuli. In comparison with groups that had exposure to S, exposure to R, or simple exposure to the apparatus, learning to inhibit R1 in S1 strongly suppressed R1 in S2. Rescorla's experiments were not designed to test or detect this effect. Thus, although Rescorla was correct that response inhibition may be strongest in the S in which it is learned, the animal also learns to stop making the response in a more general way. That more general form of response inhibition allows transfer of inhibition to a different S. Importantly, however, that response inhibition is controlled by (is specific to) its context (e.g., Todd et al., 2014). Thus, the evidence suggests that the response inhibition observed here was due at least partly to the learning of an inhibitory association between the context and R.

It is worth noting that the present results suggesting that extinction of an operant response in one stimulus can transfer and inhibit the same response in a second stimulus (Experiments 3-5) bears some relation to the phenomenon known as secondary extinction in Pavlovian conditioning (e.g., Pavlov, 1927). In secondary extinction, when two Pavlovian CSs are first conditioned, extinction of responding to one CS can transfer and suppress responding to the other CS (e.g., Pavlov, 1927). Recent research on Pavlovian secondary extinction suggests that the phenomenon is not inevitable, however; the effect appears to be restricted to conditions in which the two CSs first receive intermixed conditioning trials within the same sessions, as if some intra-session association between them is necessary (Vurbic & Bouton, 2011; Vurbic, Winterbauer, Dumais, & Bouton, 2012). Those conditions were not met in the present experiments, where we routinely found that extinction of S1R1 transferred to S2R1 (but not S3R2) when S1R1 and S2R1 had been trained in separate sessions. The difference may be consistent with the possibility that learning to inhibit the response, which was necessary (Experiment 1) and sufficient (Experiments 2-5) to suppress operant responding here, may be more important in the extinction of instrumental (operant) learning.

The results may have implications for how operant responding can be reduced by clinical treatments. First, the fact that Pavlovian exposure to S was so ineffective at weakening operant responding in S (Experiments 1, 2, and 5) is consistent with Conklin and Tiffany's (2002) observation that simple Pavlovian extinction exposure to drug-associated stimuli can have surprisingly little effect on voluntary (operant) drug taking. A major point of their review was to note that this could be due to the fact that extinction is subject to “relapse” effects such as renewal, spontaneous recovery, and reinstatement (e.g., Bouton, 1988, 1991, 2002; Vurbic & Bouton, 2014). The present results additionally suggest that Pavlovian exposure procedures may not be as effective as those that allow the client to actually learn to inhibit the operant response. However, it is important to recognize that successfully-extinguished discriminated operants may still be renewed when the context is changed (e.g., Todd et al., 2014; Vurbic et al., 2011). Second, on a more optimistic note, the fact that learning to inhibit the response in the presence of one S can transfer and suppress performance of the same response in other Ss suggests that extinction procedures that encourage response inhibition may be reasonably successful. Indeed, the fact that response inhibition created by extinction of R in S1 can transfer to S2 even when R is associated with different reinforcing outcomes in S1 and S2 (Experiment 4) suggests an additional way to build treatments. Those results suggest that inhibiting a response such as eating (or drug taking) in the presence of one stimulus can transfer and suppress the same response when it has been associated with different foods (or drugs) in the presence of other stimuli. A thorough understanding of the boundary conditions of that effect will require additional research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant RO1 DA 033123 to MEB. The participation of RC-J, who visited the University of Vermont from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, was made possible by CONACYT Abroad Research Stay Mixed Grant 290749. We thank Scott Schepers, Eric Thrailkill, and Jeremy Trott for their comments on the manuscript.

References

- Bossert JM, Liu SY, Lu L, Shaham Y. A role of ventral tegmental area glutamate in contextual cue-induced relapse to heroin seeking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:10726–10730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FR, Cifani C, Koya E, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Ventral medial prefrontal cortex neuronal ensembles mediate context-induced relapse to heroin. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:420–422. doi: 10.1038/nn.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and ambiguity in the extinction of emotional learning: Implications for exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1988;26:137–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(88)90113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. A contextual analysis of fear extinction. In: Martin PR, editor. Handbook of behavior therapy and psychological science: An integrative approach. Pergamon Press, Inc.; Elmsford, NY: 1991. pp. 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP, León SP, Miles OW, Epstein LH. Within- and between-session variety effects in a food-seeking habituation paradigm. Appetite. 2013;66:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP, Vurbic D, Winterbauer NE. Renewal after the extinction of free operant behavior. Learning & Behavior. 2011;39:57–67. doi: 10.3758/s13420-011-0018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Trask S. Role of the discriminative properties of the reinforcer in resurgence. Learning & Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0197-7. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill RM. Negative discriminative stimuli provide information about the identity of omitted response-contingent outcomes. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1991;19:326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:169–173. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gámez AM, Rosas JM. Transfer of stimulus control across instrumental responses is attenuated by extinction in human instrumental conditioning. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2005;5:207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, Choi EA, McNally GP. Paraventricular thalamus mediates context-induced reinstatement (renewal) of extinguished reward seeking. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:802–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, McNally GP. Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;151:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Newby J, McNally GP. The neural correlates and role of D1 dopamine receptors in renewal of extinguished alcohol-seeking. Neuroscience. 2007;146:525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 28. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. Occasion setting in Pavlovian conditioning. pp. 69–125. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S, Tanaka S, Urushihara K, Imada H. Renewal of extinguished lever-press responses upon return to the training context. Learning and Motivation. 2000;31:416–431. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP. Conditioned reflexes. Oxford University Press; London: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JM, Hall G. The influence of context-reinforcer associations on instrumental performance. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1979;7:504–508. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Associative relations in instrumental learning: The eighteenth Bartlett memorial lecture. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1991;43B:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Associations between a discriminative stimulus and multiple outcomes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1992a;18:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Response-independent outcome presentation can leave instrumental R-O associations intact. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1992b;20:104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Inhibitory associations between S and R in extinction. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1993;21:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Response inhibition in extinction. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section B: Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1997;50:238–252. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Solomon RL. Two-process learning theory: Relationships between Pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychological Review. 1967;74:151–182. doi: 10.1037/h0024475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP. Mechanisms of renewal after the extinction of instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2013;39:193–207. doi: 10.1037/a0032236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP, Vurbic D, Bouton ME. Mechanisms of renewal after the extinction of discriminated operant behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2014;40:355–368. doi: 10.1037/xan0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Contextual control of instrumental actions and habits. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2015a;41:69–80. doi: 10.1037/xan0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Extinction of chained instrumental behaviors: Effects of procurement extinction on consumption responding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2015b;41:232–246. doi: 10.1037/xan0000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Extinction of chained instrumental behaviors: Effects of consumption extinction on procurement responding. Learning & Behavior. 2015c doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0193-y. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapold MA, Overmier JB. The second learning process in instrumental learning. In: Black AA, Prokasy WF, editors. Classical conditioning II: Current research and theory. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1972. pp. 427–452. [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, Bouton ME. Contextual control of operant behavior: evidence for hierarchical associations in instrumental learning. Learning & Behavior. 2014;42:281–288. doi: 10.3758/s13420-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, Bouton ME. Discriminative properties of the reinforcer can be used to attenuate the renewal of extinguished operant behavior. Learning & Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0195-9. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurbic D, Bouton ME. Secondary extinction in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Learning & Behavior. 2011;39:202–211. doi: 10.3758/s13420-011-0017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurbic D, Bouton ME. A contemporary behavioral perspective on extinction. In: McSweeney FK, Murphy ES, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of operant and classical conditioning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2014. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Vurbic D, Gold B, Bouton ME. Effects of D-cycloserine on the extinction of appetitive operant learning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;125:551–559. doi: 10.1037/a0024403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurbic D, Winterbauer NE, Dumais V, Bouton ME. Secondary extinction in appetitive conditioning. 2012 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]