Abstract

Background

A broad range of tremors occur in patients with essential tremor (ET) and Parkinson's disease (PD); despite this, there are virtually no published data that focus on the patient perspective. The aims were to (1) assess the subjective experience of tremor, comparing ET and PD patients and (2) assess the clinical correlates of that experience (i.e., what specific clinical characteristics were associated with more experienced tremor)?

Methods

One hundred twenty‐one ET and 100 PD cases enrolled in a cross‐sectional, clinical‐epidemiological study underwent a detailed clinical assessment, which included a series of standardized questionnaires and neurological examination. The question, “On a typical day, how many waking hours do you have tremor in any body part?” was also administered.

Results

Essential tremor cases reported more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD cases: 10.1 ± 7.8 (median, 10.0) versus 5.5 ± 6.3 (median, 3.0) hours (P < 0.001). A small number of cases (especially ET) reported spending ≥16 h/day shaking. Greater number of hours experiencing tremor was associated with female gender, higher Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale scores, greater perceived disability, and, in ET, higher Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment scores.

Conclusions

ET patients reported more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD patients. Certain clinical characteristics tracked with more reported tremor, and the number of such hours had clear clinical ramifications—greater number of hours was associated with both psychosocial and functional consequences.

Keywords: essential tremor, Parkinson's disease, tremor, clinical

Tremor is the hallmark feature of essential tremor (ET), occurring to some degree in all patients with the disease.1 Tremor also occurs in a large majority of patients with Parkinson's disease (PD).2, 3, 4 For this reason, both of these movement disorders have been classified as tremor disorders. In ET, the main type of tremor is kinetic, although postural, intention, and rest tremors may also occur.1, 5, 6 In PD, rest tremor is a hallmark feature, although kinetic and postural tremors also occur in many patients.2, 3 In both disorders, tremor has the potential to appear at various points during the day, emerging during a variety of daily activities. For patients with tremor, there is considerable variability from moment to moment as well as variability from one day to another.7, 8

Despite the common knowledge that a variety of tremors occur in both ET and PD, there is surprisingly little written about the experience of tremor from the perspective of the patient. There are numerous unanswered questions. For example, how much time each day do patients typically experience tremor? Is this similar in ET and PD patients? Is more time with tremor associated with specific clinical characteristics or disease features? What are the psychosocial and functional correlates of increased time with tremor? These issues, which assess the patient vantage point, are at the heart of personalized medicine and help investigators and clinicians judge the efficacy of treatment.

This was a cross‐sectional clinical study of ET and PD patients. The aims were to (1) assess the subjective experience of tremor, comparing the two disorders, and (2) assess the clinical correlates of that experience (i.e., what specific clinical characteristics were associated with more‐experienced tremor)?

Patients and Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled in a clinical‐epidemiological study of movement disorders at the Neurological Institute, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC; New York, NY; 2009–2014).9 The study assessed the role of environmental toxins in disease etiology; it also assessed a wide range of clinical features. ET and PD cases observed in the most recent 5 years were identified from a computerized billing database at the Center for Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders at the Institute. PD patients were selected without respect to the presence or absence of tremor; that is, the selection was not biased toward or away from tremulous PD. It reflected “all comers.” Each case had received a diagnosis of ET or PD from their treating neurologist at the Institute and lived within 2 hours driving distance of CUMC. One of the authors (E.D.L.) reviewed the office records of all selected patients; patients with diagnoses or physical signs consistent with other movement disorders were excluded. During this review, the most recent H & Y score10 was recorded for PD cases, as was the daily dose (mg) of levodopa and daily dose (mg) of other PD medications. Based on the most recent UPDRS score,11 the relative severity of tremor versus nontremor motor phenomenology was converted into a ratio, as previously described.12

The CUMC Internal Review Board approved study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained upon enrollment.

Study Evaluation

During the assessment, a trained research assistant administered a series of structured questionnaires that collected data on: (1) demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, race, education, and number of rooms in home); (2) general medical health (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale [CIRS] score13 (range = 0–42 [maximum]; total number of prescription medications); (3) disease severity or stage (e.g., duration of symptoms; a brief 10‐item version of a 36‐item, validated tremor disability questionnaire; range = 0–100 [maximal disability]),14 taking medication to treat tremor (yes vs. no), number of ET medications, and had surgery for movement disorder; (4) psychosocial variables (e.g., “Do other people often tell you that you have tremor?”); and (5) additional variables of interest (e.g., age of symptom onset, family history of ET, family history of PD, number of cups of coffee on the day of evaluation, number of cigarettes smoked on the day of evaluation, and use of an asthma inhaler on the day of evaluation).

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD‐10) was administered; this is a self‐report 10‐item screening questionnaire for depressive symptoms (range = 0–30; greater depressive symptoms).15 The Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index16 was administered, and the question, “During the past month, how would you rate your sleep quality overall,” which was most pertinent to these analyses, was rated as very good (1), fairly good (2), fairly bad (3), or very bad (4). It also assessed the number of hours spent sleeping each night. The Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment, a 14‐item assessment of tremor‐related embarrassment (range = 0–70; maximal embarrassment)17 was administered.

As part of the Quality of Life in Essential Tremor Questionnaire,18 the question, “On a typical day, how many waking hours do you have tremor in any body part?” was administered.

During the assessment, a videotaped neurological examination was performed on ET cases. This included one test for postural tremor and five for kinetic tremor (e.g., pouring and drinking) performed with each arm (12 tests total). A neurologist specializing in movement disorders (E.D.L.) used a reliable19 and valid20 clinical rating scale, the Washington Heights‐Inwood Genetic Study of ET (WHIGET) tremor rating scale, to rate postural and kinetic tremor during each test: 0 (none); 1 (mild); 2 (moderate); and 3 (severe). These ratings resulted in a total tremor score (range = 0–36).21 The finger‐nose‐finger maneuver included 10 repetitions per arm, and intention tremor was defined as present when tremor amplitude increased during visually guided movements toward the target.6 Rest tremor was evaluated (1) while seated with arms fully supported by the patient's legs and (2) while standing with arms at rest by the patient's side and then while walking. Rest tremor was rated as present or absent.

On videotaped examination, several types of cranial tremor were assessed. Jaw and voice tremors were coded as present or absent. Neck tremor in ET was coded as present or absent and was distinguished from dystonic tremor by the absence of twisting or tilting movements of the neck, jerk‐like or sustained neck deviation, or hypertrophy of neck muscles.22 A cranial tremor score (range = 0–3) was calculated for each case based on the number of locations (jaw, voice, and neck) in which tremor was present on examination.22

Diagnoses

ET diagnoses were reconfirmed (E.D.L.) using the videotaped neurological examination and WHIGET diagnostic criteria (moderate or greater amplitude kinetic tremor [tremor rating: ≥2] during three or more tests or a head tremor, in the absence of PD, dystonia, or another cause).23 The WHIGET diagnostic criteria for ET were developed for a population‐based genetic study and, based on data from approximately 2,000 normal (nondiseased controls), these criteria carefully specify the specific examination maneuvers during which tremor should be present and the severity of tremor that should be evident during these maneuvers. These criteria have been shown to be reliable19 and valid21 and have been used routinely in Dr. Louis' epidemiological studies of ET23, 24 and those of other tremor investigators in the United States and internationally.25, 26, 27

Each PD case had received a diagnosis of PD from their treating neurologist, who was a movement disorder neurologist at the Institute. The large majority of cases were followed by these physicians over time; hence, the diagnosis was assigned on numerous occasions. To confirm these diagnoses, I reviewed the office records and excluded patients with movement disorder diagnoses other than PD and confirmed that patients with PD met London Brain Bank criteria for PD, that is: (1) bradykinesia with either rigidity, rest tremor, or postural instability; (2) presence of at least three positive criteria for PD (e.g., unilateral onset ot progressive disorder); and (3) absence of exclusion criteria (e.g., oculogyric crisis or history of repeated head injury).28

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed in SPSS software (Version 21; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). ET and PD cases were compared in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). The associations between number of waking hours with tremor and demographic and clinical variables were examined (Table 2). When variables of interest were not normally distributed (i.e., Kolmogorov‐Smirnov's test statistic P value <0.05), nonparametric tests (Mann‐Whitney's test and Spearman's correlation coefficient) were used. Primary analyses involved the comparison of number of waking hours with tremor in ET versus PD cases, first in all cases and then in an analysis limited to a smaller subsample of 35 ET and 35 PD cases matched for disease duration. A second analysis assessed the specific clinical characteristics associated with more‐experienced tremor. Given the large number of comparisons in the second analysis (n = 25; Table 2), a significant P value for the second analysis was conservatively set at <0.002 (i.e., 0.05/25); P values between 0.05 and 0.002 were viewed as marginally significant. We performed a logistic regression analysis (outcome = ET vs. PD) to determine whether number of hours reported shaking was associated with diagnosis after adjusting for gender, age of tremor onset, and taking medication to treat tremor (yes vs. no).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

| ET (n = 121) | PD (n = 100) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 69.9 ± 12.6 | 68.2 ± 8.1 | P = 0.25a |

| Male gender | 58 (47.9) | 60 (60.0) | P = 0.07b |

| Caucasian | 114 (94.2) | 92 (92.0) | P = 0.52b |

| Education, years | 16.2 ± 2.6 (16.0) | 16.6 ± 2.6 (16.0) | P = 0.25c |

| No. of rooms in home | 6.3 ± 3.1 (6.0) | 6.5 ± 2.6 (6.0) | P = 0.32c |

| General health | |||

| CIRS score | 7.4 ± 3.5 (7.0) | 6.8 ± 3.4 (6.0) | P = 0.18c |

| Total number of prescription medications | 5.0 ± 3.3 (5.0) | 5.7 ± 3.0 (5.0) | P = 0.08c |

| Disease severity or stage | |||

| Symptom duration, years | 31.7 ± 18.3 (29.0) | 7.5 ± 5.4 (6.0) | P < 0.001c |

| Total tremor score | 20.8 ± 59.6 | NA | NA |

| Tremor disability questionnaire score | 53.6 ± 25.9 | 37.9 ± 28.4 | P < 0.001a |

| Presence of rest tremor on examination | 15 (12.4) | NA | NA |

| Cranial tremor score | 0.8 ± 0.9 (0) | NA | NA |

| H & Y score | NA | 1.9 ± 0.7 (2.0) | NA |

| Taking medication to treat tremor | 66 (54.5) | 67 (67.0) | 0.06b |

| No. of ET medications | 0.8 ± 0.8 (1.0) | NA | NA |

| Daily dose of propranolol, mg | 93.6 ± 77.0 (50) | NA | NA |

| Daily dose of primidone, mg | 250.1 ± 264.8 (187.5) | NA | NA |

| Daily l‐dopa dosage, mg | NA | 560 ± 412 (400) | NA |

| Daily pramipexole dosage, mg | NA | 1.5 ± 1.8 (1.0) | NA |

| Had surgery for movement disorder | 9 (7.4) | 6 (6.0) | P = 0.67b |

| Psychosocial variables | |||

| CESD‐10 score | 7.7 ± 5.5 (7.0) | 8.6 ± 5.7 (8.0) | P = 0.22c |

| Self‐rating of sleep quality | 2.0 ± 0.8 (2.0) | 2.1 ± 0.8 (2.0) | P = 0.28c |

| Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment (long score) | 25.2 ± 16.9 | NA | NA |

| “Do other people often tell you that you have tremor?” | 73 (60.3) | 36 (36.0) | P < 0.001b |

| Additional variables of interest | |||

| Hours of sleep per night | 6.8 ± 1.3 (7.0) | 6.6 ± 1.5 (6.5) | P = 0.23c |

| Waking hours each day | 17.2 ± 1.3 (17.0) | 17.4 ± 1.5 (17.5) | P = 0.23c |

| Age on onset of symptoms | 38.2 ± 19.5 (41.0) | 60.7 ± 9.9 (61.5) | P < 0.001c |

| Ratio of tremor to nontremor motor phenomenology on UPDRS | NA | 1.9 ± 2.4 (1.7) | NA |

| Family history of ET | 34 (28.1) | 11 (11.0) | P = 0.002b |

| Family history of PD | 13 (10.7) | 20 (20.0) | P = 0.055b |

Values are mean ± SD (median) or number (percentage).

Student t test.

Chi‐square test.

Mann‐Whitney's test.

NA, not applicable.

Table 2.

Association between number of waking hours with tremor in any body part and clinical variables in ET cases and PD cases

| ET (n = 121) | PD (n = 100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, years | r = −0.09; P = 0.34a | r = −0.05; P = 0.64a |

| Genderb | 7.6 ± 6.8 (5.5) males | 6.9 ± 7.4 (4.0) males |

| 12.3 ± 8.0 (14.0) females | 3.5 ± 3.4 (2.0) females | |

| P = 0.001c | P = 0.09c | |

| Raceb | 9.8 ± 7.8 (9.5) Caucasian | 5.8 ± 6.5 (3.0) Caucasian |

| 14.9 ± 5.4 (16.0) non‐Caucasian | 2.9 ± 2.2 (2.5) non‐Caucasian | |

| P = 0.056c | P = 0.52c | |

| Education, years | r = −0.095; P = 0.30a | r = −0.09; P = 0.38a |

| No. of rooms in home | r = −0.14; P = 0.13a | r = 0.09; P = 0.39a |

| General health | ||

| CIRS score | r = −0.01; P = 0.89a | r = −0.13; P = 0.21a |

| Total no. of prescription medications | r = 0.04; P = 0.71a | r = 0.01; P = 0.96a |

| Disease severity or stage | ||

| Symptom duration, years | r = 0.14; P = 0.14a | r = −0.002; P = 0.98a |

| Total tremor score | r = 0.45; P < 0.001a | NA |

| Tremor disability questionnaire score | r = 0.44; P < 0.001a | r = 0.49; P < 0.001a |

| Presence of rest tremor on examinationb | 12.7 ± 7.8 (12.0) Yes | NA |

| 9.7 ± 7.7 (9.0) No | ||

| P = 0.14c | ||

| Cranial tremor score | r = 0.17; P = 0.06a | NA |

| H & Y score | NA | r = 0.20; P = 0.17a |

| Taking medication to treat tremorb | 11.3 ± 7.8 (12.0) Yes | 6.0 ± 6.0 (4.0) Yes |

| 8.6 ± 7.5 (6.0) No | 4.6 ± 7.0 (1.0) No | |

| P = 0.051c | P = 0.02c | |

| No. of ET medications | r = 0.09; P = 0.31a | NA |

| Daily dose of propranolol, mg | r = 0.01; P = 0.96a | NA |

| Daily dose of primidone, mg | r = −0.18; P = 0.37a | NS |

| Daily l‐dopa dosage, mg | NA | r = 0.13; P = 0.34a |

| Daily pramipexole dosage, mg | NA | r = −0.28; P = 0.24a |

| Had surgery for movement disorderb | 11.0 ± 6.6 (10.0) Yes | 4.8 ± 5.4 (3.0) Yes |

| 10.0 ± 7.9 (10.0) No | 5.6 ± 6.4 (3.0) No | |

| P = 0.58c | P = 0.80c | |

| Psychosocial variables | ||

| CESD‐10 score | r = 0.22; P = 0.02a | r = 0.17; P = 0.09a |

| Self‐rating of sleep quality | r = 0.17; P = 0.069a | r = 0.07; P = 0.47a |

| Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment (long score) | r = 0.35; P = 0.001a | NA |

| “Do other people often tell you that you have tremor?”b | 11.0 ± 7.6 (11.0) Yes | 6.8 ± 6.5 (4.0) Yes |

| 9.0 ± 8.0 (6.5) No | 4.9 ± 6.2 (2.0) No | |

| P = 0.17c | P = 0.02c | |

| Additional variables of interest | ||

| Age on onset of symptoms | r = −0.20; P = 0.03a | r = −0.05; P = 0.67a |

| Ratio of tremor to nontremor motor phenomenology on UPDRS | NA | r = 0.13; P = 0.43a |

| Family history of ETb | 11.4 ± 7.3 (11.5) Yes | NA |

| 9.5 ± 7.9 (8.0) No | ||

| P = 0.19c | ||

| Family history of PDb | NA | 6.8 ± 6.3 (4.0) Yes |

| 5.2 ± 6.3 (2.0) No | ||

| P = 0.11c | ||

Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Values are mean ± standard deviation (median).

Mann‐Whitney's test.

NA, not applicable.

Results

The 121 enrolled ET cases and 100 PD cases were similar in terms of demographic factors (age, race, years of education, and number of rooms in home); there were slightly more males in the PD group, although the difference was not significant (Table 1). The two groups were similar in terms of general health (e.g., CIRS score) as well as psychosocial variables (Table 1). As expected, age of onset was younger and symptom duration was longer in ET cases than PD cases (Table 1). ET and PD cases did not differ with respect to the number of cups of coffee on the day of evaluation, number of cigarettes smoked on the day of evaluation, or use of an asthma inhaler on the day of evaluation (all P values >0.05).

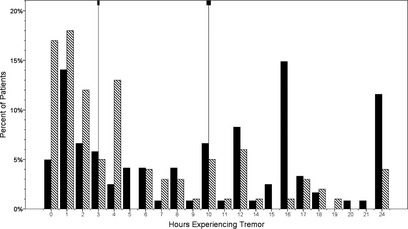

On a typical day, ET patients reported spending more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD patients (mean ± standard deviation [SD] = 10.1 ± 7.8 [median = 10.0] vs. 5.5 ± 6.3 [median = 3.0] hours; Mann‐Whitney's test = 4.48; P < 0.001; (Fig. 1). ET and PD cases did not differ in terms of the number of hours of sleep per night or number of waking hours per day (Table 1). When the percentage of waking hours spent shaking was calculated, the median value was 56.5% in ET cases and 16.7% in PD cases (Mann‐Whitney's test = 4.61; P < 0.001). Tremor disability questionnaire score was significantly higher in ET cases than PD cases (53.6 ± 25.9 vs. 37.9 ± 28.4; t = 4.25; P < 0.001; Table 1). A marginally higher proportion of PD than ET cases were taking medication to treat tremor (67 [67.0%] vs. 66 [54.5%]; χ2 = 3.54; P = 0.06; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Hours experiencing tremor in a typical day: ET versus PD. On a typical day, ET patients (black bars) reported spending more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD patients (stripped bars). Medians, shown by vertical lines, were 10.0 (ET) versus 3.0 (PD) hours (Mann‐Whitney's test = 4.48; P < 0.001).

ET and PD cases differed substantially in terms of symptom duration. However, symptom duration was not associated with number of waking hours with tremor (Table 2); hence, the difference between ET and PD cases in number of waking hours with tremor could not have been owing to differences in disease duration. Nevertheless, to further exclude this possibility, a subsample of 35 ET and 35 PD cases was selected who were matched for disease duration (12.5 ± 4.6 vs. 12.5 ± 4.8 years; Mann‐Whitney's test = 0.56; P = 0.58); in this subsample, the number of waking hours with tremor was greater in ET cases than PD cases (8.9 ± 8.2 vs. 5.4 ± 5.7 hours; Student t test = 2.10; P = 0.04). We also performed a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we stratified ET and PD cases into those who were retired versus those who were still working, given that activity level (and therefore time with tremor) may differ with respect to this variable. In both strata, ET cases spent more time with tremor than PD cases (respective Mann‐Whitney's tests = 4.49 [P < 0.001] among ET and PD cases still working and 2.11 [P = 0.03] among ET and PD cases who were retired). Second, in a logistic regression analysis that adjusted for gender, age of tremor onset, and taking medication to treat tremor (yes vs. no), ET cases reported more time shaking than PD cases (P = 0.04). Third, because our ET and PD cases were largely ascertained from a tertiary referral center, and the ET cases might have been more likely to self‐refer for severe tremor than PD cases, who may have self‐referred for other symptoms (e.g., severe bradykinesia), we performed an analysis in which we excluded all ET cases with any tremor severity rating of 3 (severe tremor) on videotaped examination; even in this analysis, the median number of hours with reported tremor was twice as high in ET than PD cases (respective medians = 6 vs. 3 hours; Mann‐Whitney's z = 2.84; P = 0.004).

The number of waking hours experiencing tremor was not associated with age or most other demographic variables; however, in ET cases, it was significantly higher in women than men (P < 0.001; Table 2). It was not associated with measures of general health (Table 2) or symptom duration (Table 2). In ET and PD cases, more hours experiencing tremor was associated with higher tremor disability questionnaire score (P < 0.001) and, in ET cases, with higher total tremor score (P < 0.001) and marginally with cranial tremor score (Table 2). In both ET and PD, cases who were taking medication to treat tremor reported marginally more waking hours with tremor than those who were not taking such medication (Table 2). Cases who had movement disorder surgery experienced similar waking hours with tremor in comparison to those who had not had such surgery (Table 2). In terms of psychosocial variables, more waking hours experiencing tremor was associated with marginally higher CESD‐10 scores (ET and PD), marginally poorer self‐rating of sleep (ET), and higher Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment score (ET; P = 0.001; Table 2). It was not associated with family history in ET or PD (Table 2). In PD cases, it was not associated with daily l‐dopa dosage, daily pramipexole dosage, H & Y score, or ratio of tremor to nontremor motor phenomenology on the UPDRS (Table 2). In an analysis in which the ratio of tremor to nontremor motor phenomenology on the UPDRS was stratified into quartiles, PD cases in the highest quartile (i.e., the most tremor on UPDRS) reported experiencing, on average, 7.9 waking hours of tremor versus PD cases in the lowest quartile (i.e., the least tremor on UDPRS) who reported experiencing an average of only 5.7 hours of tremor, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.49).

Discussion

On a daily basis, ET patients experienced far more time with tremor than PD patients. In the current study, they reported more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD patients.

In absolute terms, ET patients experienced tremor during a majority (median = 10) of their waking hours, whereas PD patients did not, reporting a median of only 3 hours of shaking. Of interest is that a small number of patients (especially ET) reported spending 16 or more hours per day shaking, indicating that some of these patients felt that the tremor was present during night‐time hours. In ET, there was a modest association between greater number of waking hours with tremor and poorer sleep quality.

The current report assessed self‐reported waking hours with tremor. Evidence that this subjective assessment of tremor severity was somewhat valid is observed in the robust association between this measure and an objective measure, the total tremor score. Moreover, the functional aspects of greater number of self‐reported hours with tremor is observed in the robust correlation with the tremor disability score, and the observation that both greater number of waking hours with tremor and greater tremor disability was observed in ET than PD. Waking hours experiencing tremor was associated with greater CESD‐10 scores and higher Essential Tremor Embarrassment Assessment scores in ET, indicating the presence of psychosocial consequences.

A marginally higher proportion of PD than ET cases were taking medication to treat tremor. However, there was no association in PD between number of hours with tremor and l‐dopa or pramipexole dosage, the two most commonly used medications. The higher proportion of PD than ET cases who were taking medication to treat tremor could reflect several possibilities. First, in PD, the same medications were likely also being used to treat other motor features (e.g., bradykinesia). Second, in ET, the poor efficacy of medications29 could have contributed to the withdrawal of patients from medication, despite greater perceived tremor severity.

A number of demographic and clinical features were associated with the number of waking hours experiencing tremor. Women with ET reported more hours with tremor than men, despite the fact that the total tremor score was similar in women and men (Mann‐Whitney's test = 0.28; P = 0.78). Previous studies have shown that women have a greater susceptibility to body dissatisfaction than men.30

Patients who had movement disorder surgery experienced similar waking hours with tremor in comparison to those who had not had such surgery. This could reflect a greater disease severity among those patients who undergo surgery, despite therapeutic benefits. Indeed, among ET cases, the total tremor score among those who underwent surgery was higher than that of those who had not undergone surgery (Student t test = 2.65; P = 0.009).

Previous work has indicated that self‐reports of tremor can be higher than actual time with tremor. Pareés et al.31 noted that patients with organic tremor reported 28% more tremor than actigraphy recordings and those with psychogenic tremor reported 65% more tremor than actigraphy. The data reported here were based on self‐report, and it would be of additional interest to determine whether there were actigraphic differences between ET and PD cases.

One question is whether the question (“On a typical day, how many waking hours do you have tremor in any body part?”) has the same validity in the assessment of tremor in PD and ET cases. ET and PD cases in our study were also asked to rate the severity of tremor in their right and left arms. We examined the correlation between the above‐referenced question (“How many waking hours do you have tremor in any body part?”) and self‐rated severity of tremor. For ET, the correlations were as follows: Spearman's r = 0.42 (P < 0.001) in the right arm and Spearman's r = 0.48 (P < 0.001) in the left arm. The correlations in PD were strikingly similar to those observed in ET: Spearman's r = 0.47 (P < 0.001) in the right arm and Spearman's r = 0.48 (P < 0.001) in the left arm. This provides some evidence that the question (“How many waking hours do you have tremor in any body part?”) has similar construct validity in both PD and ET.

In an analysis in which the ratio of tremor to nontremor motor phenomenology on the UPDRS was stratified into quartiles, PD cases in the highest quartile (i.e., the most tremor on UPDRS) reported experiencing, on average, 7.9 waking hours of tremor versus PD cases in the lowest quartile (i.e., the least tremor on UDPRS) who reported experiencing an average of only 5.7 hours of tremor, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.49). However, this variable was problematic for several reasons. First, it was based on a single (i.e., the most recent) UPDRS score. Second, the UPDRS score was extracted from the chart; it had been assigned by the treating physician and there were multiple treating physicians. Third, data were missing in many patients.

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Given the absence of a videotaped examination on PD cases, UPDRS scores and measures of tremor severity were derived from clinical records that involved many raters. Hence, the study was not able to assess the severity of rest tremor in the PD cases with any degree of precision. Second, these results reflect the experience in one study cohort and additional studies are needed. Third, some of the ET and PD cases might have been undergoing medication adjustments and/or were not optimally treated, which could have influenced the amount of tremor they were experiencing. We did not adjust for this. Finally, the use of DaTSCAN would have added greater diagnostic certainty in this study, and the use of accelerometry would have provided greater characterization of tremor severity.

In summary, ET patients reported more than 3 times the median number of waking hours experiencing tremor than PD patients. Certain clinical characteristics tracked with more reported tremor, and the number of such hours had clear clinical ramifications—greater number of hours was associated with both psychosocial and functional consequences.

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NINDS #R01 NS039422). The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: Dr. Louis has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [NINDS] no.: R01 NS042859, as principal investigator [PI]; NINDS no.: R01 NS39422 [PI]; NINDS no.: R01 NS086736 [PI]; NINDS no.: R01 NS073872 [PI]; NINDS no.: R01 NS085136 [PI]; NINDS no.: T32 NS07153‐24 [PI]; NINDS no.: R21 NS077094 [co‐investigator]; and NINDS no.: R01 NS36630 [co‐investigator]. He has also received support from the Parkinson's Disease Foundation. He also acknowledges the support of NIEHS P30 ES09089 and the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1 TR000040).

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Sternberg EJ, Alcalay RN, Levy OA, Louis ED. Postural and intention tremors: a detailed clinical study of essential tremor vs. Parkinson's disease. Front Neurol 2013;4:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brennan KC, Jurewicz EC, Ford B, Pullman SL, Louis ED. Is essential tremor predominantly a kinetic or a postural tremor? A clinical and electrophysiological study. Mov Disord 2002;17:313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lance JW, Schwab RS, Peterson EA. Action tremor and the cogwheel phenomenon in Parkinson's disease. Brain 1963;86:95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koller WC, Vetere‐Overfield B, Barter R. Tremors in early Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 1989;12:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen O, Pullman S, Jurewicz E, Louis ED. Rest tremor in patients with essential tremor: prevalence, clinical correlates, and electrophysiologic characteristics. Arch Neurol 2003;60:405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Louis ED, Frucht SJ, Rios E. Intention tremor in essential tremor: prevalence and association with disease duration. Mov Disord 2009;24:626–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pulliam CL, Eichenseer SR, Goetz CG, et al. Continuous in‐home monitoring of essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mostile G, Fekete R, Giuffrida JP, et al. Amplitude fluctuations in essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Louis ED, Factor‐Litvak P, Liu X, et al. Elevated brain harmane (1‐methyl‐9H‐pyrido[3,4‐b]indole) in essential tremor cases vs. controls. Neurotoxicology 2013;38:131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967;17:427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fahn S, Elton RL; of the UPDRS Development Committee Members . Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne BD, Goldstein M, eds. Recent Developments in Parkinson's Disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Health Care Information; 1987:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. Variable expression of Parkinson's disease: a base‐line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. The Parkinson Study Group. Neurology 1990;40:1529–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968;16:622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Louis ED, Barnes LF, Wendt KJ, et al. Validity and test‐retest reliability of a disability questionnaire for essential tremor. Mov Disord 2000;15:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES‐D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Traub RE, Gerbin M, Mullaney MM, Louis ED. Development of an essential tremor embarrassment assessment. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:661–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Troster AI, Pahwa R, Fields JA, Tanner CM, Lyons KE. Quality of life in Essential Tremor Questionnaire (QUEST): development and initial validation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2005;11:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Louis ED, Ford B, Bismuth B. Reliability between two observers using a protocol for diagnosing essential tremor. Mov Disord 1998;13:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Louis ED, Wendt KJ, Albert SM, Pullman SL, Yu Q, Andrews H. Validity of a performance‐based test of function in essential tremor. Arch Neurol 1999;56:841–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Louis ED, Pullman SL. Comparison of clinical vs. electrophysiological methods of diagnosing of essential tremor. Mov Disord 2001;16:668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Louis ED, Rios E, Rao AK. Tandem gait performance in essential tremor: clinical correlates and association with midline tremors. Mov Disord 2010;25:1633–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Louis ED, Ford B, Wendt KJ, Lee H, Andrews H. A comparison of different bedside tests for essential tremor. Mov Disord 1999;14:462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Louis ED, Marder K, Jurewicz EC, Watner D, Levy GL, Mejia‐Santana H. Body mass index in essential tremor. Arch Neurol 2002;59:1273–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inzelberg R, Mazarib A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Friedland R. Essential tremor prevalence is low in Arabic villages in Israel: door‐to‐door neurological examinations. J Neurol 2006;253:1557–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gasparini M, Bonifati V, Fabrisio E, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in essential tremor: a preliminary study. J Neurol 2001;248:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Putzke JD, Uitti RJ, Obwegeser AA, Wszolek ZK, Wharen RE. Bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation: midline tremor control. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:684–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hughes AJ, Ben‐Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. What features improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinson's disease: a clinicopathologic study. Neurology 1992;42:1142–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diaz NL, Louis ED. Survey of medication usage patterns among essential tremor patients: movement disorder specialists vs. general neurologists. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:604–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Louis ED, Michalec M. Validity of a screening question for head tremor: an analysis of four essential tremor case samples. Neuroepidemiology 2014;43:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pareés I, Saifee TA, Kassavetis P, et al. Believing is perceiving: mismatch between self‐report and actigraphy in psychogenic tremor. Brain 2012;135(Pt 1):117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]