Abstract

Short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) may be associated with several psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD). Short LTL has previously been associated with poor response to psychiatric medications in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, but no studies have prospectively assessed the relationship of LTL to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response in MDD. We assessed pre-treatment LTL, depression severity [using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)], and self-reported positive and negative affect in 27 healthy, unmedicated adults with MDD. The subjects then underwent open-label treatment with an SSRI antidepressant for 8 weeks, after which clinical ratings were repeated. The analyses were corrected for age, sex, and body mass index. ‘Non-responders’ to treatment (HDRS improvement <50%) had significantly shorter pre-treatment LTL than ‘responders’ (p = 0.037). Further, shorter pre-treatment LTL was associated with less improvement in negative affect (p < 0.010) but not with changes in positive affect (p = 0.356). This preliminary study is the first to assess the relationship between LTL and response to SSRIs in MDD and among the first to prospectively assess its relationship to treatment outcome in any psychiatric illness. Our data suggest that short LTL may serve as a vulnerability index of poorer response to SSRI treatment, but this needs examination in larger samples.

Key Words: Affect, Affective disorder, Antidepressants, Biomarker, Depression, Major depression, Mood disorders, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, Telomere, Treatment response

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe and disabling disorder [1] that is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the leading cause of disability, affecting an estimated 350 million people worldwide. Although the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying MDD are not fully known, changes in cellular aging, indexed by shortened leukocyte telomeres, may be a novel aspect of MDD pathophysiology [2,3].

Telomeres are specialized DNA nucleoprotein complexes that, along with bound protective proteins, cap the chromosomal ends of DNA, serving to protect the chromosomes from damage and to promote genomic stability and integrity [4]. When somatic cells divide, telomeres may not be fully replicated due to the ‘end replication problem’ [4]. Further, cumulative exposure to certain cytotoxic environments, such as oxidative stress and inflammation, may lead to telomere shortening [4]. Consequently, the average human telomere length [TL; often assessed in leukocytes as leukocyte TL (LTL) or peripheral blood mononuclear cells] generally shortens with age unless acted upon by telomerase, the major telomere-lengthening enzyme, or by alternative telomere-lengthening mechanisms [4,5]. When telomeres become critically shortened, the genome may become unstable and/or the cell may undergo senescence, causing activation of cellular mechanisms that promote dysfunction and disease, such as inflammation, mitochondrial damage, proliferation failure, and cell death [2,4].

Recent studies have investigated TL in relation to numerous psychiatric disorders [[2], unpubl.], and several studies have shown shortened TL in MDD [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], although exceptions exist [14,15,16]. Shortened LTL in MDD and other psychiatric disorders could have pathophysiological significance by indicating accelerated aging at the cellular level and by synergizing with depression diagnosis in predicting mortality in certain populations [17]. However, few studies have investigated the association between LTL and psychopharmacological outcomes. To date, only three studies (one in bipolar disorder and two in schizophrenia) have examined the relationship between LTL and treatment response to psychiatric medications [18,19,20], two of which assessed clinical treatment outcomes retrospectively [18,19]. Martinsson et al. [18] retrospectively assessed lithium response in 121 patients with bipolar disorder and found that lithium non-responders had significantly shorter LTL than responders. Yu et al. [19] retrospectively evaluated clinical response to antipsychotics in a group of 68 inpatients with schizophrenia and found that poorer treatment response was associated with shorter LTL. Li et al. [20] assessed TL in 89 first-episode, antipsychotic-naïve patients with schizophrenia prior to beginning 8 weeks of open-label risperidone treatment and found that patients with poorer treatment response (<50% symptom improvement after treatment) had shorter LTL. Additionally, a placebo-controlled study by Rasgon et al. [21] examined LTL as a predictor of antidepressant response to the addition of pioglitazone (a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist) in 42 patients with unremitted MDD who were already attempting to treat their depression with (an)other medication(s). This study found that patients with shorter LTL showed a poorer response to the addition of pioglitazone to their medication therapy, and this relationship was not seen in the placebo group.

However, no study has yet assessed the relationship between pre-treatment LTL and clinical response to a traditional antidepressant medication in MDD. Based on these prior studies, we hypothesized that shorter pre-treatment LTL would be associated with poorer observer-rated response to antidepressant medication in MDD. Secondary outcomes included self-reported changes in negative and positive affect.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Twenty-eight unmedicated adults (20-65 years of age) with current MDD were enrolled in an 8-week longitudinal study of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment. Telomerase and LTL data on 13 of these subjects were reported previously [22,23]; however, none of these subjects had data previously presented on the relationship between LTL and treatment response. One of the 28 enrolled subjects was excluded due to the detection of periodontitis (an exclusionary criterion) during the course of antidepressant treatment, leaving 27 completing subjects. Subjects were recruited by flyers, bulletin board notices, Craigslist postings, newspaper advertisements, and clinical referrals.

All subjects were diagnosed with MDD, without psychotic features, according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID) [24] with a current 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [25] rating of ≥17. SCID diagnoses were confirmed by clinical interview with a board-certified psychiatrist. Subjects were excluded for presence of the following: bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms during their current major depressive episode, history of psychosis outside of a mood disorder episode, any eating disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder within 1 month of entering the study, and substance abuse or dependence (including alcohol) within 6 months of entering the study. Comorbid anxiety disorders (except post-traumatic stress disorder) were allowed if MDD was considered the primary diagnosis.

The study participants had no acute illnesses or infections, chronic inflammatory disorders, neurological disorders, or any other major medical conditions considered to be potentially confounding (e.g. cancer, HIV, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease or stroke, etc.), as assessed by history, physical examinations, and routine blood screening. All subjects were free of psychotropic medications (including antidepressants), hormone supplements, and steroid-containing birth control or other potentially interfering medications, and had not had any vaccinations, for at least 6 weeks prior to enrolment in the study, and none were taking vitamin supplements above the US recommended daily allowances (e.g. 90 mg/day for vitamin C). Short-acting sedative-hypnotics were allowed as needed up to a maximum of 3 times per week, but none within 1 week prior to participation. Prior to each study visit, all subjects had to pass a urine toxicology screen for drugs of abuse (marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, phencyclidine, opiates, methamphetamine, tricyclic antidepressants, and barbiturates) and a urine test for pregnancy for women of child-bearing age.

Procedures

The subjects were admitted as outpatients to the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Clinical and Translational Science Institute between the hours of 08:00 and 11:00, having fasted (except water) since 22:00 h the night before. They were instructed to sit quietly and relax for 25-45 min before blood samples were obtained for LTL assessment and routine clinical laboratory assessments were made to determine health. The severity of depressive symptoms was then rated using the HDRS [25], and positive and negative affect over the previous 7 days was rated using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [26]. PANAS data were only available for 20 of the subjects due to incomplete self-ratings from 7 subjects.

To account for other variables that could affect TL and/or treatment response, we also assessed the following: (1) subjective stress using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [27], (2) the level of physical activity using the ‘vigorous activity’ section of the Yale Physical Activity Survey (YPAS) [28], and (3) estimated lifetime depression chronicity using the life history charting methods described by Post et al. [29]. Clinical ratings and history-taking were performed blinded to TL.

Following this baseline visit, the subjects completed 8 weeks of open-label outpatient treatment with an SSRI antidepressant, as determined to be clinically appropriate by the study psychiatrist. The decision regarding the specific SSRI prescribed was made based on clinical grounds, such as medical history, family history, and potential side effects. To limit the range of treatments, the choice of medication was limited to SSRI. The prescriber was blinded to TL. Assessments of outpatient compliance with the medication regimen, as well as clinical evaluations and assessments of drug tolerability, were made by a telephone check-in at the end of week 1 and an in-person check-in at the end of week 4 and week 8, at which time pill counts were performed. Thirteen of the subjects additionally had plasma antidepressant concentrations assessed at week 4 and week 8; in each of these subjects, plasma antidepressant concentrations were in the reported clinical range for that antidepressant, suggesting excellent compliance. Twenty subjects were treated with sertraline, 2 with fluoxetine, 2 with citalopram, and 3 with escitalopram. Medication dosages increased over the course of treatment as tolerated and as warranted by clinical response. Sertraline dosing began with 25 mg per day and increased to a maximum of 200 mg per day; fluoxetine and citalopram dosing began with 10 mg per day and increased to a maximum of 40 mg per day, and escitalopram dosing began with 10 mg per day and increased to a maximum of 20 mg per day. See table 1 for further information regarding SSRI dosing. At the end of the 8 weeks of SSRI treatment, the subjects were again rated with the HDRS and PANAS. Subjects with improvement <50% on the HDRS following treatment were defined as ‘non-responders’ and those with improvement ≥50% were defined as ‘responders’ [30].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

| Total (n = 27) | Non-responders (n = 12) | Responders (n = 15) | Non-responders vs. responders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.56±11.73 | 43.33±13.23 | 32.93±8.14 | U = 44.0, p = 0.024 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 10/17 | 4/8 | 6/9 | χ2 = 0.13, p = 0.726 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian/non-Caucasian), n | 20/7 | 8/4 | 12/3 | χ2 = 0.62, p = 0.432 |

| Years of education | 16.15±1.98 | 16.00±2.56 | 16.27±1.44 | U = 83.0, p = 0.724 |

| Household income1, USD | 39,406±26,169 | 43,500±31,035 | 35,313±21,589 | U = 58.5, p = 0.643 |

| BMI | 26.86±4.81 | 29.39±4.37 | 24.84±4.26 | U = 38.5, p = 0.012* |

| Current tobacco users (users/non-users), n | 9/18 | 3/9 | 6/9 | χ2 = 0.68, p = 0.411 |

| Alcohol consumption2, number of drinks | 15.65±3.33 | 20.38±5.34 | 10.92±3.73 | U = 50.0, p = 0.199 |

| HDRS pre-treatment rating | 19.63±3.32 | 19.25±3.39 | 19.93±3.35 | U = 86.5, p = 0.860 |

| HDRS post-treatment rating | 9.78±4.58 | 13.75±2.77 | 6.60±2.92 | U = 6.0, p < 0.001* |

| PANAS negative scale pre-treatment rating3 | 41.75±9.58 | 41.44±9.57 | 42.00±10.05 | U = 49.0, p = 0.970 |

| PANAS negative scale post-treatment rating3 | 27.75±5.20 | 29.11±4.23 | 26.64±5.84 | U = 36.5, p = 0.321 |

| PANAS positive scale pre-treatment rating3 | 26.85±5.03 | 25.22±3.15 | 28.18±5.98 | U = 34.0, p = 0.235 |

| PANAS positive scale post-treatment rating3 | 37.85±10.44 | 33.00±5.20 | 41.82±12.13 | U = 33.5, p = 0.223 |

| YPAS vigorous activity index score4 | 259.08±336.21 | 374.22±427.37 | 166.96±214.39 | U = 64.5, p = 0.207 |

| Lifetime depression chronicity5, months | 141.24±115.99 | 158.58±122.91 | 123.89±121.39 | F = 0.48, p = 0.494 |

| Baseline subjective stress score6 | 24.61±6.19 | 26.20±5.67 | 23.38±6.51 | U = 47.5, p = 0.276 |

| Final SSRI dose7, mg/day | 99.07±34.31 | 112.50±34.86 | 88.33±32.55 | U = 52.0, p = 0.067 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD unless specified otherwise.

Significant at the 0.05 level.

Household income reported by 16 participants (8 responders and 8 non-responders).

Self-reported approximate number of drinks in the month prior to baseline blood draw; data were available for 24 participants (12 responders and 12 non-responders).

PANAS data only include those from participants who completed the scale at both the pre-treatment and the post-treatment time point; data were available for 20 participants (11 responders and 9 non-responders).

The YPAS vigorous activity index score is derived as follows: ‘frequency score’ × ‘duration score’ × participant's weight (in kg); frequency scores range from 0 to 4 and duration scores from 0 to 3 [28].

Data are age adjusted using ANCOVA; lifetime depression chronicity was estimated using the life history charting methods described by Post et al. [29]; only periods of time during which subjects met the DSM-IV criteria for MDD were counted.

Baseline subjective stress was measured using the PSS [27]; scores range from 0 to 40, where higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived stress; data were available for 23 participants (13 responders and 10 non-responders).

Data for final SSRI dose are based on the dose equivalency of sertraline [46].

TL Measurement

High-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from frozen whole blood (obtained at baseline) using commercially available reagents (Puregene, Gentra Systems; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif., USA). DNA quality and quantity were assessed with a nanodrop spectrophotometer, and random samples were also assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The TL measurement assay was adapted from the published original method [31]. Briefly, the T (telomeric) and S (single-copy gene) values of each sample were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primers: tel1b [5′-CGGTTT(GTTTGG)5GTT-3′] and tel2b [5′- GGCTTG(CCTTAC)5CCT-3′] for T, and hbg1 (5′-GCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC-3′) and hbg2 (5′-CACCAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3′) for S (human β-globin). Genomic DNA from HeLa cells was used as the reference to quantify the T and S values relative to the reference DNA sample by the standard curve method. All PCRs were carried out on a Roche LightCycler 480 real-time PCR machine with 384-tube capacity (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind., USA). The telomere thermal cycling profile consisted of: (a) cycling for T PCR: denature at 96°C for 1 min; denature at 96°C for 1 s, anneal/extend at 54°C for 60 s, with fluorescence data collection, 30 cycles; (b) cycling for S PCR: denature at 96°C for 1 min; denature at 95°C for 15 s, anneal at 58°C for 1 s, extend at 72°C for 20 s, 8 cycles; then denature at 96°C for 1 s, anneal at 58°C for 1 s, extend at 72°C for 20 s, hold at 83°C for 5 s with data collection, 35 cycles. To control for inter-assay variability, 8 control DNA samples were included in each run.

In each batch, the T/S ratio of each control DNA was divided by the average T/S for the same DNA from 10 runs to obtain a normalizing factor. This was done for all 8 control samples, and the average normalizing factor for all 8 samples was used to correct the participant DNA samples in order to obtain the final T/S ratio. The T/S ratio for each sample was measured twice. If the duplicate T/S value and the initial value varied by >7%, the sample was run a third time and the average of the two closest values was reported. Using this method, the inter-assay coefficient of variation for TL measurement was 4%. Details of this method can be found in Lin et al. [32]. For presentation of the data, T/S ratios were converted to base pairs (bp) by the formula: bp = 3,274 + 2,413 × (T/S). TL assays were performed in two separate batches [13 samples in the first batch (9 responders and 4 non-responders) and 14 samples in the second batch (6 responders and 8 non-responders)]. As noted below, ‘batch’ was entered as a covariate in all analyses. Laboratory personnel who performed the assay were blinded to demographic and clinical data.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). All tests were 2-tailed with α = 0.05. p values between 0.05 and 0.10 are reported as trends. Comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics between groups (responders vs. non-responders) were performed using Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests, with the exception of lifetime depression chronicity (in months), which was compared using ANCOVA to correct for age. All data of interest were normally distributed. Age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) were a priori defined as covariates, due to their reported impact on LTL; therefore, all analyses were corrected for age, sex, and BMI. Additionally, as LTL was analysed in two separate assay batches, all analyses were also corrected for assay batch. To evaluate the impact of other potential confounders, bivariate correlations were assessed between ethnicity, BMI, current tobacco use, current alcohol use, level of physical activity, household income, years of education, subjective stress, lifetime depression chronicity, and the measures investigated in this study (LTL, HDRS rating, and PANAS rating); no significant associations were found.

To examine our hypothesis that pre-treatment LTL predicts clinical response to SSRI treatment, we assessed by ANCOVA whether ‘non-responders’ to treatment had pre-treatment LTLs significantly different to those of ‘responders’, including age, sex, BMI, and LTL assay batch as covariates. To further explore the relationship between LTL and clinical response to SSRI treatment, Pearson correlations were performed to examine associations between pre-treatment LTL and the absolute change in HDRS depression severity ratings and the absolute change in PANAS total negative and positive affect ratings (week 8 minus baseline). Correlations were performed using residual values corrected for age, sex, BMI, and LTL assay batch. Confidence intervals for Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated using Fisher's z transform.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Response

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are summarized in table 1. As expected, HDRS and PANAS ratings significantly improved over the 8-week course of open-label SSRI treatment. Absolute HDRS ratings declined from 19.63 ± 3.32 to 9.78 ± 4.58 (p < 0.001), representing a mean decrease of 49.2%. Clinical ‘response’ was defined a priori as reduction in HDRS rating by 50% or greater [30]. By this definition, 15 participants (55.6%) were ‘responders’ and 12 (44.4%) were ‘non-responders’. Absolute PANAS negative affect ratings declined from 41.75 ± 9.58 to 27.75 ± 5.20 (p < 0.001), representing a mean decrease of 30.6%. Absolute PANAS positive affect ratings increased from 26.85 ± 5.03 to 37.85 ± 10.44 (p < 0.001), representing a mean increase of 43.6%.

When comparing the demographics and clinical characteristics of responders with those of non-responders (table 1), we see that non-responders were older (p = 0.024) and had a higher BMI (p = 0.012) than responders. There were no significant between-group differences in sex, ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, physical activity level, SSRI dose, lifetime depression chronicity, or any baseline clinical measure examined (PSS, PANAS, or HDRS rating).

Pre-Treatment TL and Clinical Response

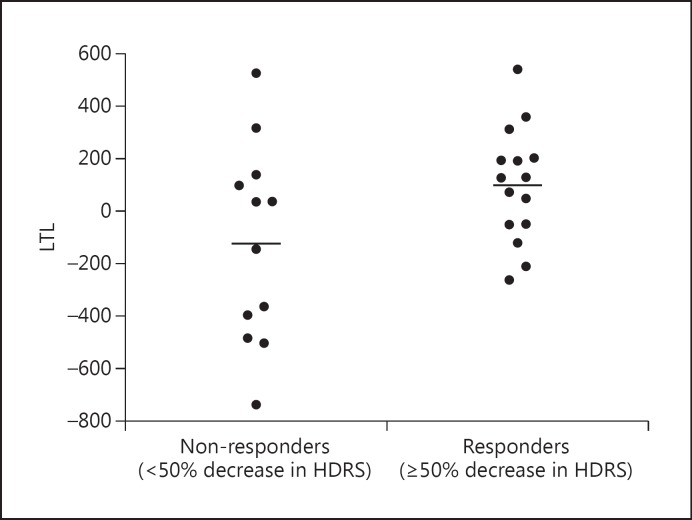

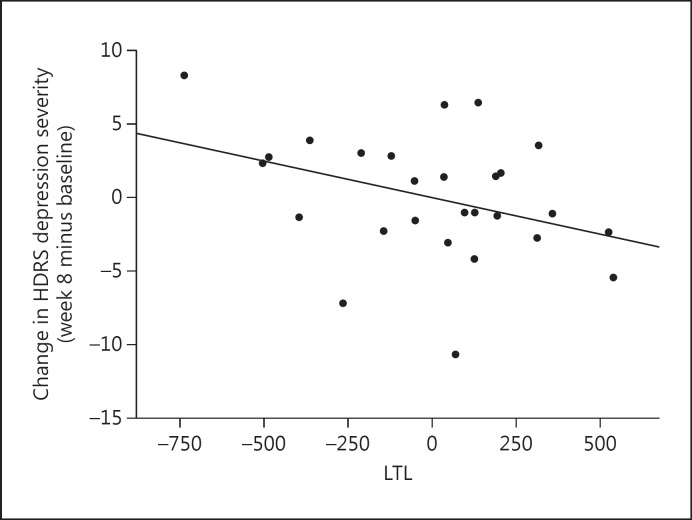

Non-responders had significantly shorter pre-treatment LTL than responders [means (adjusted for age, sex, and BMI): 5,470.03 ± 354.18 vs. 5,801.62 ± 346.39 bp; F(1, 21) = 4.985, p = 0.037, 95% CI −640.439 to −22.477, d = 0.947; fig. 1). The 5 lowest adjusted LTL values in the data set belonged to non-responders; these individuals were examined and were not found to be different from the rest of the sample in regard to age (range 20-58 years) or any other demographic or baseline clinical value, so they were not influentially driving the results. Further, shorter pre-treatment LTL was associated with less absolute improvement in HDRS ratings at the trend level (r = −0.367, p = 0.060, 95% CI −0.655 to 0.016; fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Pre-treatment LTL in subjects classified as responders (≥50% decrease in HDRS ratings over the 8 weeks of treatment) and non-responders (<50% decrease in HDRS ratings over the 8 weeks of treatment) [F(1, 21) = 4.985, p = 0.037, 95% CI −640.44 to −22.74, d = 0.947]. Data represent residual values after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and LTL assay batch; therefore, LTL data may be positive or negative.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between pre-treatment LTL and absolute change in HDRS depression severity over the 8 weeks of treatment (week 8 minus baseline) (r = −0.367, p = 0.060, 95% CI −0.655 to 0.016). Data represent residual values after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and LTL assay batch; therefore, data may be positive or negative.

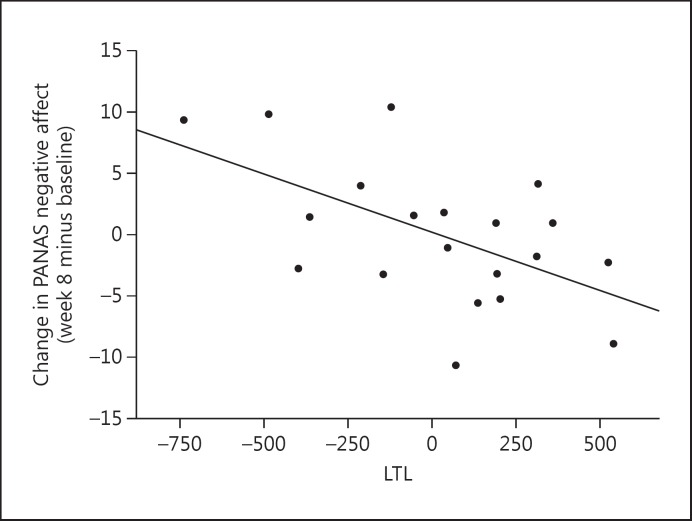

Lastly, shorter pre-treatment LTL was associated with less improvement in PANAS negative affect (r = −0.562, p = 0.010, 95% CI −0.804 to −0.158; fig. 3), but not with changes in PANAS positive affect (r = 0.218, p = 0.356, 95% CI −0.249 to 0.602).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between pre-treatment LTL and absolute change in PANAS negative affect over the 8 weeks of treatment (week 8 minus baseline) (r = −0.562, p = 0.010, 95% CI −0.804 to −0.158). Data represent residual values after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and LTL assay batch; therefore, data may be positive or negative.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between LTL and clinical response to traditional antidepressants in MDD and is among the first to prospectively assess the relationship between LTL and psychopharmacological treatment response in any disease [see also 20, 21]. We found that pre-treatment LTL was shorter in depressed individuals who subsequently did not respond to SSRI treatment (≤50% improvement in depression ratings) compared to those who did respond; this difference was determined to represent a large effect, as indicated by Cohen's d. Consistent with these findings, we found a trend toward shorter pre-treatment LTL predicting less decline in absolute depression severity ratings, as well as significantly predicting less improvement in negative, but not positive, affect (dimensions that are considered orthogonal to each other [33]). Regarding the latter finding, it is interesting to note that at least one previous study that examined positive and negative features separately [34] found that LTL was negatively associated with pessimism ratings, but not significantly correlated with optimism ratings, in post-menopausal women. These findings do not appear to be related to ethnicity, current tobacco use, current alcohol use, the level of physical activity, household income, years of education, subjective stress, lifetime depression chronicity, or differences in SSRI dosing, which were similar by group and were not related to baseline LTL. Although non-responders were significantly older and had a significantly higher BMI than responders, our findings were significant after statistically correcting for these factors.

Four previous studies (reviewed in the Introduction) reported that shorter LTL is associated with worse psychiatric response to medications, i.e. lithium in bipolar disorder [18], antipsychotics in schizophrenia [19,20], and the addition of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist in unremitted MDD [21]. Our study differs from, and adds to, these previous findings in several ways. The present study (1) examined LTL and treatment response to a traditional antidepressant in MDD; (2) used standardized rating instruments and utilized a prospective, rather than retrospective, assessment of treatment response (as did half of the previously mentioned studies), yielding a more accurate evaluation of treatment response; (3) used a clinically relevant treatment intervention administered by a single physician, lessening extraneous factors that could affect treatment response; (4) was performed on depressed individuals who had been medication free for more than 6 weeks prior to having LTL assessed and commencing treatment, allowing us to assess clinical response to the SSRI relative to an unmedicated state; (5) employed stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, ruling out individuals with potentially confounding medications, illnesses, or comorbid conditions, and (6) had demographic data available regarding BMI, the level of physical activity, current alcohol and tobacco use, socioeconomic status, subjective stress, and lifetime depression chronicity, allowing these to be statistically controlled for where appropriate.

Though specific pathways are not known, putative mechanisms by which LTL regulation may be associated with antidepressant outcomes can be postulated. Several peripherally assessed biological systems have been independently associated with both shorter LTL and worse clinical response to antidepressants, including higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [22,34,35,36,37,38,39], oxidative stress [40], and more early adverse life events [41,42]. However, several of these findings are based on small samples and/or require replication. Though we did not specifically test these mechanisms in this study, it is possible that shorter LTL indexes peripheral biochemical conditions (e.g. greater oxidative stress or inflammation) or life histories (trauma exposures) that bode ill for antidepressant response. In addition, certain mechanisms may more directly link short leukocyte telomeres with poorer antidepressant response. For example, senescent CD8+ T cells with short telomeres (CD8+CD28-) hypersecrete pro-inflammatory cytokines [43], which might adversely affect antidepressant response [44]. However, since we did not assess T cell subpopulations in this study, and since we do not have cytokine data available, we cannot directly test this hypothesis. Thus, shorter LTL may be an indirect reflection of some other processes that correlate with poor antidepressant response (e.g. inflammation or oxidative stress), or it may have an intrinsic predictive value, although this seems less likely. In a previous small-scale study, we reported that relatively high pre-treatment peripheral blood mononuclear cell telomerase activity was associated with poorer response to sertraline [23]. The present finding that shorter leukocyte telomeres are also associated with poorer response to SSRIs may complement these findings, though any mechanistic linkage is speculative.

Limitations

Limitations of the present study include (1) the use of a relatively small sample (particularly for the PANAS variables); (2) the assessment of mixed leukocytes, making it difficult to determine if TL in specific leukocyte subpopulations is more closely related to treatment response and whether LTL differences reflect TL differences on a ‘per cell’ basis versus a shift in circulating leukocyte subpopulations; (3) the open-label nature of the antidepressant therapy, which can confound drug response with placebo response (though an open-label design more closely resembles clinical settings and was a common factor across all study participants); (4) the assessment of antidepressant response after 8 weeks of treatment, rather than additionally including longer durations, and (5) the study of only one class of antidepressant, the SSRIs.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that LTL may be a novel biomarker for predicting open-label SSRI treatment response, although these findings must be considered preliminary, pending larger-scale replication. If these and other emerging data are replicated, the telomere system may emerge as a novel locus of interest for clinical psychopharmacology [2,45].

Statement of Ethics

The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved the study protocol. All study participants gave written informed consent to participate in this study and were compensated for participating, in addition to receiving free antidepressant treatment.

Disclosure Statement

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. None of the granting or funding agencies had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The co-principal investigators O.M.W., E.S.E., and S.H.M. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

J.L. is a consultant to Telomere Diagnostics Inc., formerly Telome Health Inc., a diagnostics company related to telomere biology, and owns stock in the company. The company had no role in this research or in writing this paper. The remaining authors report no disclosures.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Kevin Delucchi, PhD, Phuong Hoang, and Alanie Lazaro (all at the UCSF), the nursing and other staff of the UCSF CTSI Clinical Research Center, and all past and present UCSF PNE Lab volunteer research assistants.

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; grant No. R01-MH083784), the O'Shaughnessy Foundation, the Tinberg family, the UCSF Academic Senate, the UCSF Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (REAC), and the Bernard and Barbro Foundation. This project was also supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources (NIH/NCRR) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH (through UCSF-CTSI grant No. UL1 RR024131). D.L. was supported by the Swedish Research Council (registration No. 2015-00387) and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, COFUND, Project INCA 600398.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindqvist D, Epel ES, Mellon SH, Penninx BW, Révész D, Verhoeven JE, Reus VI, Lin J, Mahan L, Hough CM, Rosser R, Bersani FS, Blackburn EH, Wolkowitz OM. Psychiatric disorders and leukocyte telomere length: underlying mechanisms linking mental illness with cellular aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:333–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verhoeven JE, Révész D, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Cellular aging in depression: permanent imprint or reversible process? An overview of the current evidence, mechanistic pathways, and targets for interventions. Bioessays. 2014;36:968–978. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan SR, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:109–121. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draskovic I, Londono Vallejo A. Telomere recombination and alternative telomere lengthening mechanisms. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2013;18:1–20. doi: 10.2741/4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Wong KK. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhoeven JE, Révész D, Epel ES, Lin J, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and accelerated cellular aging: results from a large psychiatric cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:895–901. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wikgren M, Maripuu M, Karlsson T, Nordfjäll K, Bergdahl J, Hultdin J, Del-Favero J, Roos G, Nilsson LG, Adolfsson R, Norrback KF. Short telomeres in depression and the general population are associated with a hypocortisolemic state. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann N, Boehner M, Groenen F, Kalb R. Telomere length of patients with major depression is shortened but independent from therapy and severity of the disease. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:1111–1116. doi: 10.1002/da.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoen PW, de Jonge P, Na BY, Farzaneh-Far R, Epel E, Lin J, Blackburn E, Whooley MA. Depression and leukocyte telomere length in patients with coronary heart disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:541–547. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821b1f6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lung FW, Chen NC, Shu BC. Genetic pathway of major depressive disorder in shortening telomeric length. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:195–199. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32808374f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The association between depression and leukocyte telomere length: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:229–238. doi: 10.1002/da.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai N, Chang S, Li Y, et al. Molecular signatures of major depression. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1146–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon NM, Walton ZE, Bui E, Prescott J, Hoge E, Keshaviah A, Schwarz N, Dryman T, Ojserkis RA, Kovachy B, Mischoulon D, Worthington J, DeVivo I, Fava M, Wong KK. Telomere length and telomerase in a well-characterized sample of individuals with major depressive disorder compared to controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaakxs R, Verhoeven JE, Oude Voshaar RC, Comijs HC, Penninx BW. Leukocyte telomere length and late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Needham BL, Mezuk B, Bareis N, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Epel ES. Depression, anxiety and telomere length in young adults: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:520–528. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J, Blalock JA, Chen M, Ye Y, Gu J, Cohen L, Cinciripini PM, Wu X. Depressive symptoms and short telomere length are associated with increased mortality in bladder cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:336–343. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinsson L, Wei Y, Xu D, Melas PA, Mathé AA, Schalling M, Lavebratt C, Backlund L. Long-term lithium treatment in bipolar disorder is associated with longer leukocyte telomeres. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e261. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu WY, Chang HW, Lin CH, Cho CL. Short telomeres in patients with chronic schizophrenia who show a poor response to treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33:244–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Hu M, Zong X, He Y, Wang D, Dai L, Dong M, Zhou J, Cao H, Lv L, Chen X, Tang J. Association of telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number with risperidone treatment response in first-episode antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18553. doi: 10.1038/srep18553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasgon N, Lin KW, Lin J, Epel E, Blackburn E. Telomere length as a predictor of response to pioglitazone in patients with unremitted depression: a preliminary study. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e709. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, Reus VI, Rosser R, Burke HM, Kupferman E, Compagnone M, Nelson JC, Blackburn EH. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress - preliminary findings. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Reus VI, Rosser R, Burke H, Compagnone M, Nelson JC, Dhabhar FS, Blackburn EH. Resting leukocyte telomerase activity is elevated in major depression and predicts treatment response. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:164–172. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM, Nadel ER. A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:628–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Post RM, Roy-Byrne PP, Uhde TW. Graphic representation of the life course of illness in patients with affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:844–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.7.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lecrubier Y. How do you define remission? Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002;415:7–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.106.s415.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Epel E, Cheon J, Kroenke C, Sinclair E, Bigos M, Wolkowitz O, Mellon S, Blackburn E. Analyses and comparisons of telomerase activity and telomere length in human T and B cells: insights for epidemiology of telomere maintenance. J Immunol Methods. 2010;352:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacKinnon A, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Pers Individ Diff. 1999;27:405–416. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donovan A, Lin J, Tillie J, Dhabhar FS, Wolkowitz OM, Blackburn EH, Epel ES. Pessimism correlates with leukocyte telomere shortness and elevated interleukin-6 in post-menopausal women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:446–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, Maier W, Mors O, Hauser J, Dernovsek MZ, Henigsberg N, Souery D, Farmer A, McGuffin P. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortriptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:1278–1286. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14010094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eller T, Vasar V, Shlik J, Maron E. Pro- inflammatory cytokines and treatment response to escitalopram in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang HH, Lee IH, Gean PW, Lee SY, Chi MH, Yang YK, Lu RB, Chen PS. Treatment response and cognitive impairment in major depression: association with C-reactive protein. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin JP, Weng NP, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Révész D, Verhoeven JE, Milaneschi Y, de Geus EJ, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Dysregulated physiological stress systems and accelerated cellular aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1422–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behr GA, Moreira JC, Frey BN. Preclinical and clinical evidence of antioxidant effects of antidepressant agents: implications for the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:609421. doi: 10.1155/2012/609421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klengel T, Binder EB. Gene × environment interactions in the prediction of response to antidepressant treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:701–711. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shalev I, Entringer S, Wadhwa PD, Wolkowitz OM, Puterman E, Lin J, Epel ES. Stress and telomere biology: a lifespan perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Effros RB. Kleemeier Award Lecture 2008 - the canary in the coal mine: telomeres and human healthspan. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:511–515. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Brien SM, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Scott LV, Dinan TG. Plasma cytokine profiles in depressed patients who fail to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bersani FS, Lindqvist D, Mellon SH, Penninx BW, Verhoeven JE, Révész D, Reus VI, Wolkowitz OM. Telomerase activation as a possible mechanism of action of psychopharmacological interventions. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:1305–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Preskorn S. Outpatient Management of Depression. ed 3. Caddo: Professional Communications; 2009. [Google Scholar]