Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to describe a case of ocular rosacea with a very complex evolution. Rosacea is a chronic dermatological disease that may affect the ocular structures up to 6-72% of all cases. This form is often misdiagnosed, which may lead to long inflammatory processes with important visual consequences for affected patients. Therefore, an early diagnosis and an adequate treatment are important.

Methods

We report the case of a 43-year-old patient who had several relapses of what seemed an episode of acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Two weeks later, he developed a corneal ulcer with a torpid evolution including abundant intrastromal infiltrators and calcium deposits. He was diagnosed with ocular rosacea and treated with systemic doxycycline and topical protopic.

Results

A coating with amniotic membrane was placed in order to heal the ulcer, but a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty to restore the patient's vision because of the corneal transparency loss was necessary.

Conclusions

Ocular rosacea includes multiple ophthalmic manifestations ranging from inflammation of the eyelid margin and blepharitis to serious corneal affectations. A delayed diagnosis can result in chronic inflammatory conditions including keratinization and loss of corneal transparency, which lead to important visual sequelae for affected patients.

Keywords: Rosacea, Ocular symptoms, Management, Amniotic membrane, Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic skin disease of unknown etiology. It is characterized by the appearance of a persistent erythema, papules, pustules and telangiectasia in varying degrees in the forehead skin, cheeks, nose and chin in a symmetrical distribution [1]. Sometimes the lesions may appear on extrafacial sites exposed to ultraviolet radiation such as the retro-auricular area, sternum, neck or back of the scalp [2].

Females are more often affected than males, but the latter show more severe forms such as rhinophyma. Disease onset is usually between the third and fifth decades of life, but manifestations can occur throughout life course [3, 4].

Although the signs are predominantly dermatological, ocular involvement may be present in 6–72% of the patients [5]. This entity is often misdiagnosed, which can lead to devastating consequences.

The main ocular signs include periorbital swelling, eyelid margin erythema and telangiectasia; blepharitis and Meibomian gland affectation; conjunctivochalasis, dry eye and bacterial colonization; erosion, corneal neovascularization and thinning or even perforation [6], and episcleritis and scleritis [5, 7].

The predominant symptom is ocular blepharoconjunctivitis [8], but up to 33% of the patients develop corneal injuries that can affect their vision seriously, mainly due to delayed diagnosis [9]. The dysfunction of the Meibomian glands can lead to evaporative dry eye syndromes. In fact, some studies have shown increased tear osmolarity and tear dysfunction in patients with ocular rosacea [10].

The aim of this paper is to present the case of a 43-year-old male with symptoms of ocular rosacea with a torpid evolution because of the initial diagnostic complexity.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old male came to emergency services after 2 days of pain in his left eye (OS). There was no medical history except for right-eye evisceration because of a penetrating trauma when he was younger.

The ophthalmological examination revealed a visual acuity (VA) of 20/20. He presented great conjunctival hyperemia with abundant mucous-purulent secretions. The rest of his examination appeared to be normal. He was diagnosed with acute bacterial conjunctivitis. We recommended washing the eye with saline solution and treatment with topical tobramycin and diclofenac drops every 8 h.

Five days later, the patient returned due to pain in his OS. Ophthalmic examination was unchanged except for the appearance of periorbital erythema in both eyes. No changes to the treatment were made. Two days later, he returned because of a clinical worsening. Physical examination revealed eyelid margin telangiectasias, eyelid erythema and edema; not only great secretions but also conjunctival hyperemia. His ocular motility was normal, and there was no change in the rest of the examination. He was diagnosed of preseptal cellulitis, and at the insistence of the patient, he was admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate 1 g/200 mg every 8 h and ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 h, continuing his topical treatment.

The patient was discharged after 5 days. However, given the persistence of ocular nuisances and abundant secretions, we performed a culture of the conjunctival exudate, which was negative, and he continued with topical antibiotic treatment.

Two days after discharge, he returned to emergency with great pain in his OS. His VA had decreased to 20/25. The conjunctival hyperemia, amount of secretions and eyelid inflammation had not improved, and he had developed a central corneal debridement with infiltration. We advised occlusion, cycloplegic every 8 h, and we changed the topical antibiotic to moxifloxacin every 4 h and intense lubrication.

Two days later, the cornea ulcer had central deposits and infiltration, endothelial edema, and his VA had fallen to 20/100. The patient was hospitalized, and we started treatment with intravenous vancomycin and ceftazidime as well as intravenous corticosteroids, drops of ceftazidime and vancomycin alternating every 2 h, cycloplegic every 8 h and artificial tears without preservatives profusely.

We performed a new analysis of conjunctival and corneal exudate cultures, which were also negative. Because of the persistence of inflammation and periocular erythema, we consulted with dermatology service, which reached the diagnosis of rosacea and started topical tacrolimus (Protopic 0.1%) twice daily on reddened skin. For treating the ocular inflammation, we developed a preservative-free ointment of tacrolimus 0.02% dissolving prograf capsules with vaseline and used it twice daily. We also started systemic treatment with doxycycline 100 mg every 12 h for 1 month.

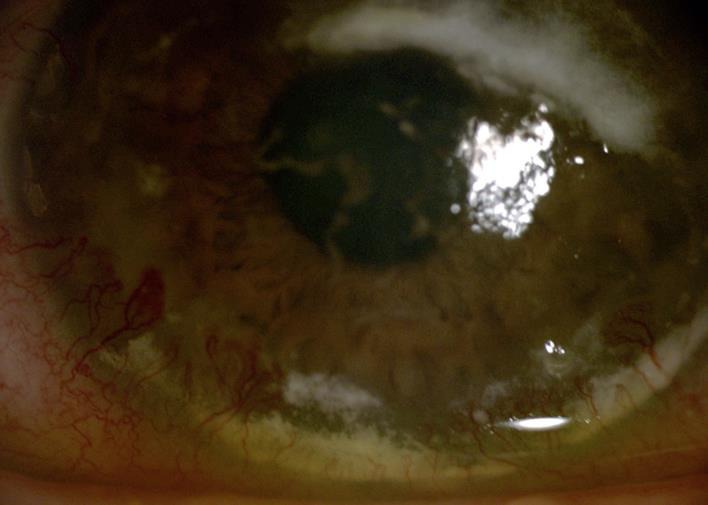

During the next weeks, the ulcer showed partial closure processes followed by reactivations (fig. 1). Calcium deposits appeared, and thicker areas with a partial closure of the ulcer were observed.

Fig. 1.

Corneal ulcer with infiltration and endothelial edema.

We decided to perform amniotic membrane transplantation to treat the great inflammatory component and the chronicity of the ulcer using the patch technique. After its reabsorption 2 weeks later, the keratopathy was completely closed, but a calcium deposit where the ulcer was located persisted (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Calcium deposits and partial closure of the ulcer.

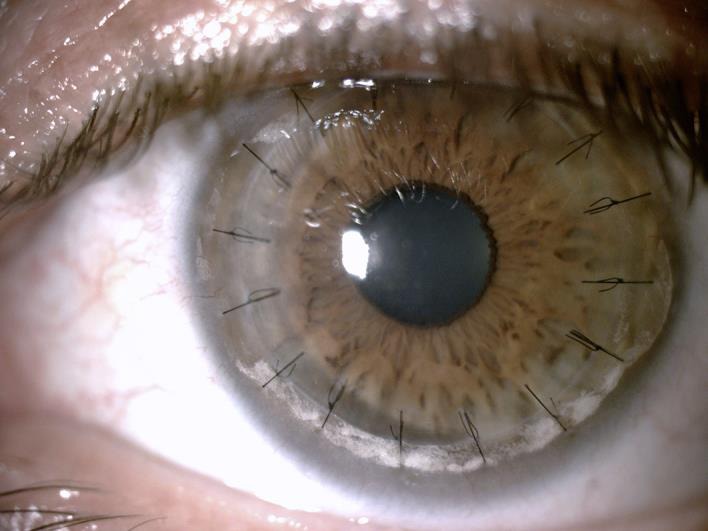

When the patient's condition was established, we proposed the possibility of a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty for the removal of the calcareous keratopathy and restoration of his corneal transparency (fig. 3). We used oral and ocular corticosteroids to avoid corneal rejection, reserving the systemic and topical tacrolimus for the case that new rosacea episodes appeared. One year after the transplant, the patient is asymptomatic, his VA has improved to 20/30 and the cornea retains its transparency. No other episodes of rosacea reactivation have developed.

Fig. 3.

State of the cornea after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty.

Discussion

Ocular rosacea is a frequently misdiagnosed entity that can cause severe visual disabilities. Ocular manifestations may precede, follow or occur simultaneously with skin changes, but most commonly they develop jointly. The most common ocular signs include blepharitis, conjunctival injection, eyelid margin telangiectasias, changes in the Meibomian glands such as chalazion or stye or scales and crusts on the eyelids [5, 8, 9].

Corneal damages are more severe and can include signs as punctate keratopathy, corneal vascularization and corneal thinning and perforation. This involvement is usually bilateral but asymmetric. It is common to find limbal vessel dilation associated with rosacea conjunctivitis. Punctate keratitis, subepithelial infiltrates or nodular elevations can be present. Sometimes epithelial cysts develop; they can rupture and form ulcers and recurrent corneal epithelial erosions very resistant to treatment [10, 11]. Nowadays, the standard treatments include eyelid hygiene, oral tetracycline, corticosteroids and lubrication of the ocular surface.

Oral doxycycline has been the mainstay of treatment for ocular rosacea but seems to provide only moderate benefit and has many side effects, limiting its usage [7, 12]. Systemic cyclosporine has been used as an immune suppressant. It inhibits T-lymphocyte activation, proliferation and migration as well as cell apoptosis. Oral doxycycline has also been used as drops to deal with ocular surface inflammation [7, 12, 13]. Other immunemodulator drugs, such as topical tacrolimus, are supposed to have positive effects on ocular rosacea [14], although its isolated use was not very effective in our patient. We decided to perform amniotic membrane transplantation to control the ocular surface inflammation because the epithelial defect persisted in time despite the use of systemic or topical immune suppressors. Some authors described the use of amniotic membrane transplantation to control corneal inflammation and avoid neovascularization [15]. In cases where the corneal transparency is involved, corneal transplant may be needed to restore it.

Nevertheless, ocular treatment alone is not sufficient to alleviate the symptoms so that in most cases, it is necessary to treat the skin involvement simultaneously. Treatment duration is patient-dependent and is intended to control and prevent relapses.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial interest to disclose relevant to this work.

References

- 1.Jackson JM, Knucles M, Minni JP, Johnson SM, Belasco KT. The role of brimonidine tartrate gel in the treatment of rosacea. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:529–538. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S58920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheinfeld N, Berk T. A review of the diagnosis and treatment of rosacea. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:139–143. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen T, Plewig G. Rosacea: classification and treatment. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:144–150. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buechner SA. Rosacea: an update. Dermatology. 2005;210:100–108. doi: 10.1159/000082564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira AC, Höfling-Lima AL, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea-a review. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012;75:363–369. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492012000500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akpek EK, Merchant A, Pinar V, Foster CS. Ocular rosacea: patient characteristics and follow-up. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1863–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arman A, Demirseren DD, Takmaz T. Treatment of ocular rosacea: comparative study of topical cyclosporine and oral doxycycline. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:544–549. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2015.03.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Marchi SU, Cecchin E, De Marchi S. Ocular rosacea: an underdiagnosed cause of relapsing conjunctivitis-blepharitis in the elderly. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205146. pii:bcr2014205146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peralejo B, Beltrani V, Bielory L. Dermatologic and allergic conditions of the eyelid. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2008;28:137–168. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaman Erdur S, Eliacik M, Kocabora MS, Balevi A, Demirci G, Ozsutcu M, Gulkilik G, Aras C. Tear osmolarity and tear film parameters in patients with ocular rosacea. Eye Contact Lens. 2015 doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000211. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramamurthi S, Rahman MQ, Dutton GN, Ramaesh K. Pathogenesis, clinical features and management of recurrent corneal erosions. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:635–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iovieno A, Lambiase A, Micera A, Stampachiacchiere B, Sgrulletta R, Bonini S. In vivo characterization of doxycycline effects on tear metalloproteinases in patients with chronic blepharitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:708–716. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utine CA, Stern M, Akpek EK. Clinical review: topical ophthalmic use of cyclosporin A. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;8:352–361. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.498657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard LA, Cunningham BB, Al-Suwaidan S, Friedlander SF, Eichenfield LF. A rosacea-like granulomatous eruption in a patient using tacrolimus ointment for atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:229–231. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain AK, Sukhija J. Amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular rosacea. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie) 2007;39:71–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02697331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]