ABSTRACT

Lung transplantation is a globally accepted treatment for some advanced lung diseases, giving the recipients longer survival and better quality of life. Since the first transplant successfully performed in 1983, more than 40 thousand transplants have been performed worldwide. Of these, about seven hundred were in Brazil. However, survival of the transplant is less than desired, with a high mortality rate related to primary graft dysfunction, infection, and chronic graft dysfunction, particularly in the form of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. New technologies have been developed to improve the various stages of lung transplant. To increase the supply of lungs, ex vivo lung reconditioning has been used in some countries, including Brazil. For advanced life support in the perioperative period, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and hemodynamic support equipment have been used as a bridge to transplant in critically ill patients on the waiting list, and to keep patients alive until resolution of the primary dysfunction after graft transplant. There are patients requiring lung transplant in Brazil who do not even come to the point of being referred to a transplant center because there are only seven such centers active in the country. It is urgent to create new centers capable of performing lung transplantation to provide patients with some advanced forms of lung disease a chance to live longer and with better quality of life.

Keywords: Lung transplantation, Lung transplantation/contraindications, Survivorship (public health), Brazil

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary transplant is a therapeutic option accepted worldwide for the treatment of some advanced lung diseases. However, its success depends on a very strict selection of candidates, so that they may obtain a satisfactory survival and improved quality of life.

The 2014 International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry recorded the performance of 47,647 lung transplants and 3,772 combined heart-lung transplants all over the world, up to July of 2013.(1) The much lower number relative to the other solid organ transplants, such as liver, kidneys, and heart, is justifiable due to the high complexity of the procedure, with few centers in the world qualified to perform them, besides the difficulty in finding donors with lungs that meet the minimum requirements for their use.

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF PULMONARY TRANSPLANTS IN THE WORLD

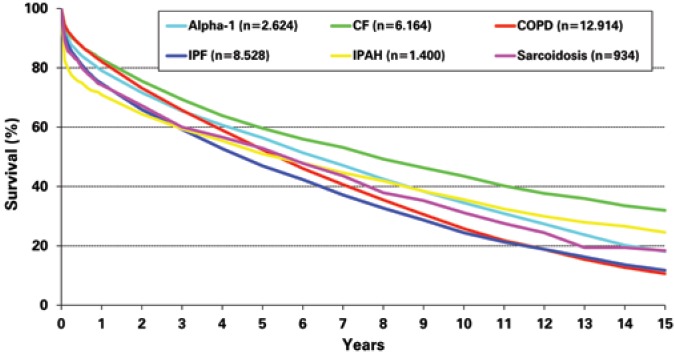

The first cardiopulmonary transplant done successfully in the world took place in 1981, and was conducted by a Stanford University team. In 1983, the team from the University of Toronto, led by Dr. Joel Cooper, successfully performed the first isolated lung transplant (unilateral transplant) in a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), who survived for 6.5 years – it was considered excellent at the time.(2) In 1986, the first double lung transplant was performed (without transplanting the heart with the lungs), and it was only in 1990 that the first bilateral sequential pulmonary transplant was done, the technique most used today all over the world.(3) The difference between the double transplant carried out previously and the bilateral sequential transplant currently done, is the anastomosis of airways. While in the double transplant the anastomosis was performed in the trachea, in the bilateral sequential operation anastomoses are made in each primary bronchus (right and left), allowing one lung to be ventilated while the other is implanted, reducing the need for extracorporeal circulation and the complications of the airway anastomoses (the incidence of trachea anastomosis dehiscence was a lot higher than the incidence of complications in the primary bronchus anastomosis). About 30% of the lung transplants are still unilateral (Figure 1). Despite a global survival lower than for bilateral transplant, this technique is still justified by the possibility of transplanting two patients with one donor, allowing the reduction of mortality on the waiting list. Additionally, for recipients older than 60 years with other comorbidities (primarily atherosclerotic disease), a shorter operating time could mean lower mortality in the early postoperative period.

Figure 1. Graph showing the evolution in number of bilateral and unilateral transplants worldwide over the years.

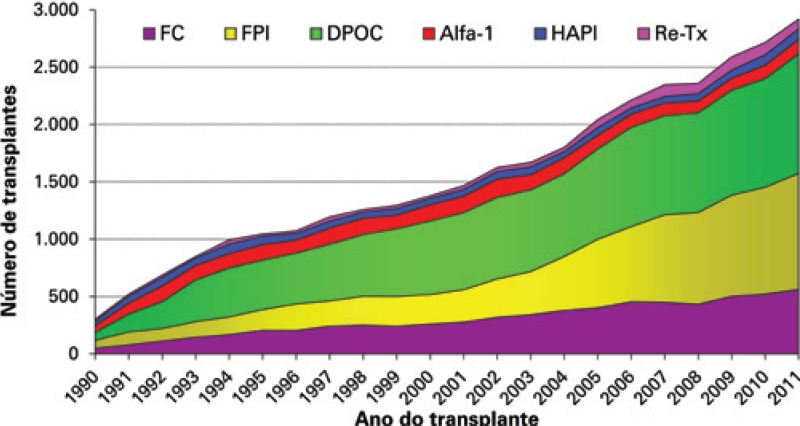

The primary indications for lung transplant in the world are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 34% of cases; IPF in 24%; cystic fibrosis (CF) in 17%; alpha-1-antitrypsin (alpha-1) deficiency in 6%; idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) in 3%; pulmonary fibrosis (non-IPF) in 4%; bronchiectasis in 3%; retransplant in 2.6%; and sarcoidosis in 2.5% (Figure 2). Other indications for lung transplant include connective tissue diseases, constrictive bronchiolitis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary hypertension secondary to congenital cardiopathies (in which the cardiac defect underwent a late correction or that may be corrected at the time of the transplant), Langerhanscell histiocytosis, and others.(4)

Figure 2. Graph showing the evolution in number of lung transplants, as per the underlying disease.

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF LUNG TRANSPLANTS IN BRAZIL

Currently, there are only seven active centers that perform lung transplantation in Brazil (two in São Paulo − SP, two in Porto Alegre − RS, one in Belo Horizonte − MG, one in Fortaleza – CE, and one in Brasília). The last registry of the Brazilian Association of Organ Transplants (ABTO, Associação Brasileira de Transplantes de Órgãos) showed a total of 810 lung transplants performed until June 2014.(5)

Lung transplant in Brazil is proportionately less frequent than of other solid organs, such as kidney and liver, although the survival results are comparable to those reported in the international literature. The high complexity of the surgical procedure and of the resources necessary to care for lung transplant patients, in addition to the need for training of the highly specialized medical team, hinders the creation of transplant centers.

Another limiting fact for the performance of more procedures is the low use of the lungs of multiple organ donors. While most of the world uses at least 20% of donor lungs, in the State of São Paulo, for example, less than 5% of donor lungs are used.(6) This is due to the poor level of care given to the donors in most hospitals of Brazil.

With the intention of improving the reuse of lungs, an ex vivo lung perfusion technique was developed in Sweden and perfected in the United States. This technique consists of a device capable of reducing the edema of the lungs that would not be reused by the criteria of gas exchange, so that, after a period on the device and after the reduction of edema, tests to reevaluate the gas exchange might be done to confirm the non-viability of the lungs, with the purpose of some of them being implanted safely. In Brazil, this technique has already been used successfully.(7) At the moment, the ex vivo project is not yet approved by the Ministry of Health for clinical use, outside the research project. The technique was used to recondition the lungs of 12 donors. However, after being maintained in the device for 4 hours, only the lungs on one donor showed the necessary conditions for implantation. The initial impression of the Brazilian group that has been conducting this research is that infection of the lungs is a problem more prevalent and more poorly managed (before diagnosis of brain death) than in other countries. The ex vivo is not capable of reconditioning infected lungs.

PRINCIPLES FOR INDICATION OF LUNG TRANSPLANTATION

Patient selection

Parallel to the increase in number of transplants performed worldwide and of the overall survival of transplanted patients, there is an increasing demand of patients candidate for treatment, leading to a disproportional increase of patients on a waiting list, and consequent greater mortality among them, considering the relative scarcity of organs for donation. Therefore, the selection of candidates for transplant should be very strict to benefit the individuals with chances of greater long-term survival.

Lung transplant may be indicated for patients with advanced pulmonary disease and those in progression, despite all the clinical and surgical therapies, and who have a reduced life expectancy. Additionally, the candidates should demonstrate knowledge as to the procedure, good compliance to the medical treatment given, and adequate psychosocial structure and family support. It is important that the patient be aware that treatment provides better quality of life longer life expectancy, but it is not curative. It is an exchange of a serious pulmonary disease for a state of chronic immunosuppression and its possible life-long complications.(8)

Contraindications

Taking into consideration the fact that it is a form of therapy with high levels of mortality, one should remember that the ideal candidate for transplant is a young patient, with advanced pulmonary disease and absence of diseases in other organs and systems, with an optimized chance of immediate and long-term survival.

Adequate evaluation of the contraindications contributes towards a lower occurrence of unfavorable clinical outcomes not related to the graft, benefiting the patients with greater chances of success, and thus, improving overall survival with the treatment.(6)

Absolute contraindications

-

–

History of neoplasm treated in the last two years (except for non-melanoma skin neoplasms).

-

–

Lung cancer: although there are reports of the use of transplant as surgical treatment for lung carcinoma, currently it is not recommended due to the high levels of systemic recurrence; the indication for localized bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is debatable, but is not accepted in the vast majority of transplant centers.

-

–

Cardiac dysfunction not related to pulmonary disease, characterized by significant left ventricular dysfunction or coronary insufficiency not treatable percutaneously; some centers admit the performance of myocardial revascularization surgery at the same time as the transplant.

-

–

Significant organic dysfunction of any other noble organ (brain, kidneys, and liver) verified by clinical history and tests for specific assessment of each organ.

-

–

Infections by hepatitis viruses B and C without control with the specific treatment.

-

–

Active pulmonary tuberculosis.

-

–

Addiction to tobacco, alcohol, narcotics, psychoactive substances, or cessation less than six months before.

-

–

Serious psychiatric disease without control or untreatable, which might interfere in compliance to treatment.

-

–

Lack of compliance to the proposed medical treatment.

-

–

Lack of social and family support.

-

–

Severe deformity of thoracic cage.

Relative contraindications

-

–

Age over 65 years. Isolated, this should not be considered an absolute contraindication, but the survival rates after 60 years of age and, especially after 65 years, are higher, especially due to the comorbidities presented by the patients and poor systemic reserve to various insults (surgery, renal and cardiac dysfunction, sepsis). The sum of these factors with the age usually corroborates the contraindication.(8)

-

–

Serious clinical instability (orotracheal intubations, extracorporeal membrane, sepsis, acute organic dysfunctions, pulmonary embolism).

-

–

Severe functional limitation of peripheral muscles with incapacity to perform outpatient rehabilitation.

-

–

Colonization by difficult to treat infectious agents (e.g., Burkholderia cenocepacia, Mycobacterium abcessus).

-

–

Infections by the HIV virus (some centers transplant patients with the virus, as long as they present with good compliance to the antiviral therapy and have an undetectable viral load).

-

–

Obesity or severe malnutrition.

-

–

Severe or symptomatic osteoporosis.

-

–

Other systemic diseases that are not adequately controlled such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, connective tissue disorders.

Reference and waiting list

The moment of inclusion on the transplant waiting list should be when the risk of the patient remaining with the disease exceeds the risk of transplant. This can be abbreviated by a 50% risk estimate of mortality in the next two or three years. This recommendation of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation is based, primarily, on data from countries where the time spent on a waiting list until the actual transplant varies from three to six months.

Current data from the Secretariat of Health of the State of São Paulo show an average waiting list time of 23 months, and to date, in the Brazilian legislation, there are no criteria to prioritize the most severly ill patients.(9) Thus, the moment of reference to the transplant center should be the earliest possible, within the context of a patient with chronic pulmonary disease presenting with clinical and functional worsening. We need to remember that chronic pulmonary diseases are heterogeneous in clinical presentation and functional decline. Therefore, patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cystic fibrosis should be referred earlier than those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as the latter group presents with a slower evolution and greater survival time at more advanced stages of the disease than the former group.

In Brazil, over the last two years, the subject of organ allocation for pulmonary transplant has been the theme of discussions at conferences and at the Technical Chamber of Lung Transplantation of the National Transplant System. Opinions differ within a same transplant team. As it is known that with the lungs, transplanting more seriously ill patients leads to greater postoperative mortality, and that the number of very ill patients on the waiting list is very high, to transplant patients by seriousness score would markedly increase the perioperative mortality, precluding the maintenance of various centers that initiated or are going to initiate their pulmonary transplant programs. What has been done, in very carefully selected cases (very serious but not yet dying, and with good chances of having a good outcome), is to request case-by-case prioritization from the Technical Chamber of Lung Transplants. In 2014, in São Paulo, two patients were transplanted in a situation of prioritization.

In general, it is always better to evaluate a patient earlier than what is indicated for inclusion on the list than excessively late. Besides a greater chance of the patient's being included on the list in due time to reach a transplant under good clinical conditions, there is also greater contact with the multidisciplinary transplant team, allowing a better education of the patient relative to the entire process of treatment. Such a fact is fundamental for compliance and the consequent success with the pulmonary transplant.

Indication criteria

Due to the absence of studies with large numbers of patients specifically for this topic, the current recommendations are based on international data registries and the opinions of specialists.(8,10) Indication criteria cannot be generalized, due to the heterogeneity of the clinical characters of the lung diseases that represent indications for transplants.

The indication for a transplant should not be based on just one factor, but on a set of clinical, laboratorial, and functional characteristics. Chart 1 describes the specific indications for the primary underlying diseases.

Chart 1. Criteria for indication as per specific disease.

| pulmonary disease | indication criteria |

|---|---|

| COPD | BODE index ≥7 |

| Exacerbation with respiratory acidosis (PaCO2 >50) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale | |

| FEV1 <20% of the predicted or associated with DLCO <20% of the predicted or heterogeneous emphysema | |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | DLCO <40% of the predicted |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | Drop in FVC >10% in 6 months |

| Pulse oximetry <88% in 6MWT | |

| Honeycombing score >2 on the chest tomography | |

| Unspecific interstitial pneumonia | DLCO <35% of the predicted 15% drop of the DLCO or 10% of the FVC in 6 months |

| Cystic fibrosis/ bronchiectasis | FEV1 <30% or rapid functional decline |

| More frequent exacerbations, need for intensive therapy, and multiresistant bacteria | |

| Repetitive hemoptysis not controlled with embolization | |

| Hypoxemia with need for continuous oxygen therapy | |

| Hypercapnia Secondary pulmonary hypertension | |

| Idiopathic pulmonary arterial disease | NYHA functional class III or IV despite optimized therapy |

| Distance covered in the 6MWT <350m or on a decline | |

| Absence of response to treatment with prostacyclin Cardiac index <2.0L/min/m² | |

| Right atrium pressure >15mmHg | |

| Sarcoidosis | NYHA functional class III or IV |

| Hypoxemia at rest | |

| Severe compromise of pulmonary volumes or of DLCO | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |

| LAM | NYHA functional class III or IV |

| Hypoxemia at rest | |

| Severe compromise of the pulmonary volumes or of DLCO | |

| Langerhans-cell histiocytosis | NYHA functional class III or IV |

| Hypoxemia at rest | |

| Severe compromise of the pulmonary volumes or of DLCO |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BODE score: BMI (body mass index), Obstruction (FEV1), Dyspnea (MRC - Medical Research Council), Exercise (6MWT − 6-minute walk test); PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the 1st second; DLCO: capacity for diffusion of carbon monoxide. FVC: forced vital capacity; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; NYHA: New York Heart Association; LAM: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

PRIMARY COMPLICATIONS

The principal cause of mortality during the perioperative period is primary dysfunction of the graft, which is non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema of varying levels of seriousness related to various factors, such as the presence of pulmonary hypertension, quality of preservation of the organ, presence of infection in the donor, use of extracorporeal circulation during surgery, ischemia time, and damage in organ reperfusion.(11) It develops during the first 72 hours posttransplant, and treatment consists of the adjustment of mechanical ventilation (protective ventilation strategy), reduction of pulmonary pressure, use of nitric oxide, volemic and hemodynamic management and, in very serious cases, use of extracorporeal support such as ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).(12)

The development of new technologies related to extracorporeal support was fundamental to improve the perioperative survival obtained in the last decade. Either way, the precise indication, and adequate installation and management are crucial for these resources to save lives, and not just be an excessive expense spent in vain.

One important cause of mortality in the perioperative period is infectious complications. These are also the major cause of mortality between one month and one year of the perioperative period. Sectioning of the bronchi, use of immunosuppressants and high-dose corticosteroids, difficulty in coughing, and the exposure of the lungs to room air make them more susceptible organs to post-transplant infections, when compared to other solid organs. In this way, there are strict recommendations accepted internationally of specific prophylaxis for pulmonary transplant.

The main infectious complications of the perioperative period are bacterial and fungal. Thus, prophylactic/ preemptive antibiotic therapy for the transplant should take into consideration the use of antibiotics by the donor and the results of cultures, sputum culture of the recipient, collected during the period when he/ she is on the waiting list, and the primary infectious agents found in the intensive care unit where the postoperative period should occur. During this period, clinical worsening (secretion, inflammatory, blood gas analysis, and hemodynamic markers), or radiological signs should be invasively investigated with bronchoscopy and broncoalveolar lavage.

Fungal infections, especially by Aspergillus sp, are very common. One frequent site of infection is bronchial anastomosis. In this way, most centers recommend some form of fungal prophylaxis at least during the first three months of the transplant.(13) Of the viral infections, the most common in the first postoperative year is by cytomegalovirus (CMV). Despite the fact that most recipients are IgG-positive for CMV, by immunosuppression and by the fact that the lungs are deposits of the virus (in addition to the gastrointestinal tract), its reactivation is very common. It is consensus in international literature to prescribe prophylaxis for CMV in the first three months of lung transplant (except for IgG-negative donors with IgG-negative recipients); the benefit of extending it for six months and up to one year is debatable in cases of risk of more serious viral disease (donor IgG-positive with recipient IgG-negative).(14) Infections by respiratory viruses may occur along the entire post-transplant progression. Both infections by CMV and by more aggressive respiratory viruses (influenza, syncytial respiratory virus, and parainfluenza) may definitively compromise the function of the graft and should be actively investigated in the case of clinical suspicion. The use of sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim is recommended for the rest of the patient's life as prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis and pneumocystosis.

Acute cellular rejection is frequent during the 1st posttransplant year (incidence of up to 65%) and normally does not represent an immediate risk to the patient. The diagnosis is made by means of transbronchial biopsy. Its treatment consists of high doses of corticosteroids for 3 to 5 days, and in refractory cases, thymoglobulin. Prevention of acute cell rejection is done with the combination of three drugs: corticosteroids, a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus), and a cell cycle inhibitor (azathioprine or mycophenolate). This combination of drugs should be maintained during the rest of the patient's life, unless there is some type of complication that justifies its suspension. For patients who evolve with chronic renal failure related to the use of calcineurin inhibitor, one option is the use of mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus or everolimus).

As of one year after the transplant, the principal cause of mortality that continues throughout the post-transplant evolution is chronic graft dysfunction, especially in the form of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Along the history of pulmonary transplant, chronic graft dysfunction has already been called chronic rejection, but it was noted that there are different causes for its onset, besides the immunological, such as respiratory virus infections, CMV infection, gastroesophageal reflux syndrome, recurring episodes of acute cell rejection, etc. Posteriorly, the nomenclature bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome was defined, including a grading of seriousness.(15) Its occurrence begins in the 3rd month post-transplant and can occur during the entire evolution. Its diagnosis is functional and is made based on an irreversible drop of 20% in the forced expiratory volume in the 1st second (FEV1) – excluding the acute causes for this occurrence, such as acute rejection and infections. Despite the focus given to the subject and of all that is studied about it, few interventions to date have been capable of modifying the disfavorable progression of the bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, which often leads to early death or to the need for retransplantation. More recently, chronic graft dysfunction has been discussed for presenting different forms. The functional, cytological and radiological differentiation of these various forms may guide the definition of specific management.(16)

A technology developed in Brazil over the last years, through a partnership between the Department of Respiratory Diseases of the Universidade de São Paulo and the Escola Politécnica of the Universidade de São Paulo, called electrical impedance tomography, was capable of differentiating ventilatory patterns in patients submitted to pulmonary transplant with the same functional alteration. Such technology may contribute to the understanding of chronic graft dysfunction in pulmonary transplant and serve as a basis for the preparation of specific treatment strategies for this condition.(17) Despite the fact that the use of this tool in transplant is still under study, we believe that it may be useful in the future for adjusting mechanical ventilation in some situations, such as primary graft dysfunction and in differentiating various ventilatory patterns in patients with a functional diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

SURVIVAL

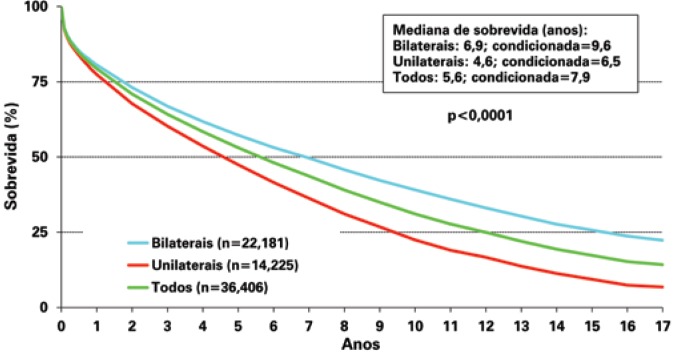

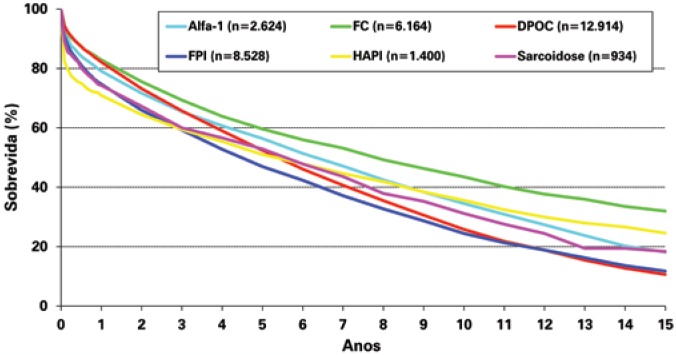

According to the 2013 ISHLT registry,(4) adults submitted to pulmonary transplant had a median survival of 5.6 years. The survival rate in three months, 1, 3, 5, and 10 years was, respectively, 88, 79, 64, 53, and 31% (Figure 3), with survival superior to that of patients submitted to bilateral transplants (median survival of 6.9 years) when compared to unilateral transplants (median survival of 4.6 years). Survival also varies according to the underlying disease, and the best life expectancy, both short- and long-term is for patients with CF (Figure 4). It is believed that the best survival of these patients is due to the fact that they are young, and since they have been sick since their birth, they acquire a culture of compliance to treatment and have family support for their condition (which is crucial for these patients to survive throughout the pretransplant years), which facilitated the rigorous post-transplant treatment. The worst perioperative survival is observed in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (idiopathic or secondary), due to right ventricle dysfunction that can worsen in the first post-transplant days and improves completely along the first weeks, and to the increased risk of serious primary graft dysfunction, often leading to the need for use of ECMO, as previously mentioned. Either way, this group of patients has the second best survival in 10 and 15 years post-transplant, justifying the indication of the procedure. The survival of bilateral pulmonary transplantat tends to be higher than that of the combined heart-lung transplant for patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IHAP), even with severe dilation and dysfunction of the right ventricle in the preoperative phase. Additionally, when a combination transplant is proposed, a patient with indication for heart transplant is not treated. In this way, the heart-lung transplant has its strict indication, in most parts of the world, for patients with congenital cardiopathies that progress with pulmonary hypertension and where the heart defect cannot be repaired during transplant.

Figure 3. Graph showing the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. In blue, the survival of bilateral transplants; in green, all transplants, and in red, unilateral transplants (p<0.0001). Conditioned survival reflects the median survival for those who survive the first year of transplant.

Figure 4. Graph showing the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for underlying diseases that most frequently lead to transplants.

CONCLUSION

The science that involves pulmonary transplant, surgical technique, indication, and postoperative management is in constant evolution and far from being established in most of its themes. In Brazil, we live with an extreme lack of new centers qualified to perform this treatment in a consistent and successful manner. There is a huge repressed demand of patients that would benefit from pulmonary transplant in Brazil, but who die without even getting on the waiting list due to the difficulties of patients in reaching a transplant center, since there are only seven active centers in Brazil.

Knowledge of the best moment to indicate and to transplant, as well as of the major complications, their prevention and management, considerably improve the results of lung transplant, which is the only effective option of treatment for several progressive and fatal pulmonary conditions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Goldfarb SB, Levvey BJ, Lund LH, Meiser B, Stehlik J, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first adult lung and heart-lung transplant report––2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(10):1009–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unilateral lung transplantation for pulmonary fibrosis. Toronto Lung Transplant Group N Engl J Med. 1986;314(18):1140–1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605013141802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper JD. The evolution of techniques and indications for lung transplantation. Ann Surg. 1990;212(3):249–255. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199009000-00003. discussion 255-6. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusen RD, Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Lund LH, Rahmel AO, Stehlik J, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirtieth Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report––2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(10):965–978. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos (ABTO) Registro Brasileiro de Transplante. Estatísticas e transplantes (Jan/Jun) 2014 [Internet] São Paulo: ABTO; 2014. [[citado 2015 Mar. 16]]. Disponível em: http://www.abto.org.br/abtov03/default.aspx?mn=457&c=900&s=0. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa da Silva F, Jr, Afonso JE, Jr, Pêgo-Fernandes PM, Caramori ML, Jatene FB. São Paulo lung transplantation waiting list: patient characteristics and predictors of death. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(3):927–931. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mariani AW, Pêgo-Fernandes PM, Abdalla LG, Jatene FB. Ex vivo lung reconditioning: a new era for lung transplantation. J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38(6):776–785. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132012000600015. Review. English, Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah PD, Orens JB. Guidelines for the selection of lung-transplant candidates. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17(5):467–473. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328357d898. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.São Paulo. Secretaria de Estado da Saúde do Estado de São Paulo . Sistema Estadual de Transplantes [Internet]. Distribuição de inscrições por tempo de espera e tipo sanguíneo: órgão Pulmão. São Paulo: Sistema Estadual de Transplantes; 2015. [[citado 2015 Maio 31]]. Disponível em: http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/transplante. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, Conte JV, Corris P, Egan JJ, Egan T, Keshavjee S, Knoop C, Kotloff R, Martinez FJ, Nathan S, Palmer S, Patterson A, Singer L, Snell G, Studer S, Vachiery JL, Glanville AR, Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update––a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(7):745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JC, Christie JD. Primary graft dysfunction. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32(2):279–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.007. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Guzman E, Davenport DL, Zwischenberger JB, Hoopes CW. Lung function and ECMO after lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(2):686–687. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.12.014. author reply 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campos S, Caramori M, Teixeira R, Afonso J, Jr, Carraro R, Strabelli T, et al. Bacterial and fungal pneumonias after lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(3):822–824. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamora MR, Davis RD, Leonard C, CMV Advisory Board Expert Committee Management of cytomegalovirus infection in lung transplant recipients: evidence-based recommendations. Transplantation. 2005;80(2):157–163. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000165430.65645.4f. Erratum in: Transplantation. 2005;80(4):545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estenne M, Hertz MI. Bronchiolitis obliterans after human lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(4):440–444. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-003pp. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd JL, Jain R, Pavlisko EN, Finlen Copeland CA, Reynolds JM, Snyder LD, et al. Impact of forced vital capacity loss on survival after the onset of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(2):156–166. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1155OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afonso JE., Jr . Análise regional da dinâmica ventilatória em transplante pulmonar com tomografia de impedância elétrica. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2010. [tese] [Google Scholar]