ABSTRACT

Given the shortage of organs transplantation, some strategies have been adopted by the transplant community to increase the supply of organs. One strategy is the use of expanded criteria for donors, that is, donors aged >60 years or 50 and 59 years, and meeting two or more of the following criteria: history of hypertension, terminal serum creatinine >1.5mg/dL, and stroke as the donor´s cause of death. In this review, emphasis was placed on the use of donors with acute renal failure, a condition considered by many as a contraindication for organ acceptance and therefore one of the main causes for kidney discard. Since these are well-selected donors and with no chronic diseases, such as hypertension, renal disease, or diabetes, many studies showed that the use of donors with acute renal failure should be encouraged, because, in general, acute renal dysfunction is reversible. Although most studies demonstrated these grafts have more delayed function, the results of graft and patient survival after transplant are very similar to those with the use of standard donors. Clinical and morphological findings of donors, the use of machine perfusion, and analysis of its parameters, especially intrarenal resistance, are important tools to support decision-making when considering the supply of organs with renal dysfunction.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, Delayed graft function, Graft survival, Renal insufficiency, Tissue donors

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplant is the replacement therapy of choice for patients with end- stage renal disease, since it provides better quality of life and greater survival for them, as compared to dialysis, besides better costeffectiveness.(1,2)

There is, however, a huge discrepancy between the number of patients on the waiting list and the number of transplants performed. According to data from the 2013 United States Renal Data System, 600 thousand patients were undergoing dialysis in the United States. At the end of 2012, 100 thousand patients were on the waiting list for a renal transplant, and approximately 17 thousand transplants are performed per year; of these, only 11 thousand are from deceased donors.(1)

The same scenario is observed in Brazil, that is, a growing increase of patients on dialysis and a large disproportion between patients on a waiting list and transplants performed. As per the 2011 Brazilian Dialysis Census, during this period there were more than 90 thousand patients undergoing dialysis.(3) According to data from January to September 2013 of the Brazilian Registry of Transplants, those active on the waiting list and with a kidney transplant were, respectively, 19,913 and 2,707 patients.(4) Many patients on the waiting list ended up dying before being called for the transplant. According to data from the São Paulo State Department of Health, 5% of patients die while waiting for a kidney transplant.(5)

Considering that this disparity between organs offered and demand for transplants is a worldwide problem, the transplant community adopted some strategies to expand the donor pool. Some strategies are: 1. to optimize the identification of potential donors by healthcare services, 2. to use donor´s heart that have stopped beating (not yet used in Brazil); 3. the use of two kidneys from the same donor of an advanced age and/or expanded criteria (in Brazil, the criteria for using two kidneys with expanded criteria have not yet been defined in an official document); 4. and in the use of expanded criteria donors (ECD).(1,6)

According to the United National Organ Sharing (UNOS), the definition of ECD is when the relative risk of losing the graft is 1.7-fold higher than the risk associated with loss of the standard donor.(7) The ECD correspond to donors aged ≥60 years or donors aged between 50 and 59 years, and who meet two or more of the following criteria: history of systemic hypertension, terminal serum creatinine >1.5mg/dL, and stroke as cause of death of the donor.(7) The survival of the graft and patient with the use of ECD was 8-12% and 15-20% lower than 3 and 5 years, respectively, compared to those of a standard donor.(8) Some studies recommend the use of ECD for older patients (>65 years), because they have a shorter life expectancy, since they would have more years of life saved than if they remained on dialysis, while for younger patients the benefits would be greater, in terms of survival, by waiting for a better quality organ and remaining less time in dialysis.(8,9) Roughly 20% of donors of the United States are ECD.(10)

The decision to accept an ECD organ should always be shared with the recipient, who should be aware of the results related to this type of transplant and decide between remaining a shorter time on the waiting list and receiving an ECD organ or waiting longer on the list, expecting a better quality organ.

Some tools are used to help the transplant physician better evaluate the viability of ECD organs, such as preimplantion renal biopsy (performed at the time of extractions), parameters of the machine perfusion,(11) and the risk scores which include clinical and morphological variables of the donor related to the quality of the organ and to the renal prognosis.(12,13)

Regarding the histological findings of the preimplant biopsy, those that are associated with the worst renal prognosis are interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy, glomerulosclerosis, vascular intimal thickening, and arteriolar hyalinosis. The most often used histological variable for discarding organs is the presence of glomerulosclerosis in more than 20% of the glomeruli. However this characteristic cannot be exclusively considered, since some studies did not confirm its association with the renal prognosis.(14–16) More recent data showed that vascular alterations, especially arteriolar hyalinosis, have a more significant effect on the survival of the graft than other histological alterations.(15,17,18) In the United States, 75% of the ECD were submitted to preimplantation biopsies, and data showed that the findings of biopsies contributed towards a better use of the organs, which would have been discarded if they had been selected merely by clinical parameters.(16)

The machine perfusion has been used to preserve the organ in several transplanting centers, because it improves quality of the organ and protects it from the ischemia-perfusion lesion,(19,20) when compared to its static preservation on ice, in kidney pairs from the same donor (any type of donor, standard or ECD), recipients who used the machine perfusion had a lower risk of delayed graft function (DGF) and better survival of the graft in one year (94% versus 90%) and in three years (91% versus 87%).(21,22) In the specific case of ECD, a meta-analysis recently showed that the use of the machine perfusion was associated with a smaller rate of DGF and better survival of the graft at one year, relative to the static preservation on ice.(23)

The perfusion machine, by means of some of its parameters, such as intrarenal flow and intrarenal resistance, allows selecting organs with greater chances of evolving with favorable results. Some centers adopted the following criteria for organ discard: intrarenal flow <80mL/min and intrarenal resistance >0.40mmHg/mL/min after 6 hours on the machine.(20,24) Likewise preimplantation biopsies, with the use of machine perfusion and analysis of its parameters, more organs were used for transplant.(16)

One of the ECD characteristics that might be present is acute kidney injury (AKI), which is considered a contraindication for accepting an organ at many centers and an important cause for discarding organs. Creatinine elevation in the donor may result from a preexisting renal disease or secondary to ischemic, nephrotoxic, immunological, and/or inflammatory injuries that occured before extraction of the organ, such as those listed, including hypotension/shock, use of nephrotoxic drugs, infection, rhabdomyolysis and/or release of cytokines related to brain death, among others. This damage most frequently causes a lesion denominated “acute tubular necrosis”, which is generally a reversible renal lesion. With the transplant, the same is expected, i.e., that aside from the damaged environment, this kidney will recover from the lesions that occurred during the preimplantation period.(1,6)

Although this lesion may generally be reversible, kidneys of donors with AKI are more susceptible to ischemic injury (resulting from warm, cold, and reperfusion ischemia), which can lead to higher rates of primary graft dysfunction, DGF, and acute rejection after the transplant.(6) Additionally, some articles showed an association with shorter graft survival, which is one of the main reasons for organs being discarded, besides the chronic morphological findings.(1,6,16,25)

On the other hand, many other studies demonstrated satisfactory results with the use of donors with AKI, who represent one more opportunity to expand the number of organs when they are strictly assessed within a clinical, histological, and functional context (machine parameters).(1,6,19,26–30)

STUDIES OF KIDNEY TRANSPLANTS PERFORMED WITH ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY DONORS AND FAVORABLE RESULTS

Farney et al. published their experience with the use of 84 deceased donors with AKI (evaluated by the donor's terminal creatinine) over five years. The definition of AKI in the donor considered in this study was terminal creatinine (before organ extraction) twice or more the baseline creatinine or terminal serum creatinine >2.0mg/dL. The mean baseline and terminal creatinine values of the donor in this study were 1.25 and 3.2mg/dL, respectively. The transplants from AKI donors presented with 5-year patient and graft survival similar to those from donors with no AKI; transplants from AKI donors had mores DGF (40% versus 27%), but this had no impact on graft survival. The renal function along two years also was not different in both groups. With these results, the group concluded that the use of deceased donors with AKI represented a safe strategy to increase the pool of donors, which can be considered for well-selected patients.(1)

Klein et al., in a Brazilian group, evaluated 1,518 individuals with transplanted kidneys, divided into four groups – 253 ECD (116 with AKI and 137 without AKI) and 1,265 standard donors (369 with AKI and 896 without AKI), and analyzed the following outcomes: DGF, kidney function, survival of the graft and patient, and one-year rejection-free survival. The use of donors with AKI led to a greater rate of DGF both in the group that used ECD (68% versus 58%) and in the group with standard donors (69.9% versus 50.6%) and when ECD was used (with and without AKI). Kidney function in one year was worse by about 10mL/min in both groups, and there were more chronic alterations in the preimplantation biopsies, as compared to those of the standard donor. The one-year survival for patient, graft and rejection-free survival was no statistically different in the four groups, suggesting that the use of these donors was related to satisfactory results.(27)

Lin et al. reported their results of about three years after the use of 25 deceased donors, whose terminal serum creatinine was >2.0mg/dL, with a mean of 3.37mg/dL. This group was based on the chronic results of preimplantation biopsies to decide as to acceptance or not of a donor organ with AKI. Using this strategy, only two kidneys with high levels of creatinine were discarded, and the group reduced the waiting time for transplant. In the same way as in the previous study, we noted a higher rate of DGF (80% versus 30%) in the group that used donors with high levels of terminal creatinine. Nevertheless, the survival rates of the patient and the graft, as well as the acute rejection rates were comparable to those of the control group.(19)

Deroure et al. showed the results of three years with the use of 52 deceased donors with AKI. The results obtained were similar to the previous ones: higher rate of DGF and optimal results for survival of the graft and patient. However, after three months, reduced renal function was noted (creatinine clearance <50mL/min), which was influenced by some variables, such as donor age, stroke as cause of death of the donor, DGF lasting longer than one week, and rejection. After these results, the authors recommended avoiding the use of kidneys from donors with AKI aged over 60 years and with a history of chronic cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, diabetes, etc.).(26)

Zuckerman et al. retrospectively assessed 17 transplants from donors with AKI and compared them to 83 transplants from donors without AKI performed during the same period. AKI was defined as terminal creatinine (before organ extraction) two-fold or more the baseline creatinine or values of terminal serum creatinine >2.0mg/dL. The mean terminal creatinine and creatinine clearance was 3.1mg/dL versus 1.3mg/dL and 44mL/min versus 98mL/min, respectively. The machine perfusion was used in 92% and 41% of cases, respectively. There was no difference between the two groups relative to the outcomes analyzed: DGF (32% versus 22%), 1 year survival of the graft and patient, acute rejection rate, days of hospitalization, and renal function in the 6th month.(24)

Greenstein et al. described a three-year experience with the use of 22 kidneys of standard donors, but with high terminal creatinine (mean serum creatinine of 3.2mg/dL). Most kidneys were preserved in machine perfusion. The incidence of DGF was 28% and all the biopsies revealed only findings consistent with acute tubular necrosis. At the end of one year after the transplant, both survival of the graft and of the patient were 100%, and the mean serum creatinine was 1.7mg/dL.(28)

A review of the UNOS results relative to transplants, both from standard donors and from ECD, stratified into three groups as per the terminal creatinine values (≤1.5mg/dL, 1.6 to 2.0mg/dL, and >2.0mg/dL), showed that, in the group of standard donors, the rate of graft loss was similar in all three groups, but there was greater discard of organs in the group with the highest creatinine value. In the groups that used ECD, both the rate of graft loss and of organ discard were greater in the group with highest levels of creatinine. In both donor groups, the greater the DGF rate, the higher the creatinine level. The use of machine perfusion led to fewer donor organs with high creatinine (>2.0mg/dL) to be discarded. This study showed that the presence of AKI in the standard donor did not impact the graft survival, while in ECD, the risk of graft loss increased as creatinine level rose.(25)

Lee et al. recently published their retrospective results related to the use of donors with AKI, classified as per the Acute Kidney Injury Network Criteria (AKIN). The outcomes analyzed were DGF, long- and short-term kidney function – as this was one of the studies with longest follow-up. In this study, 28% of the recipients received organs with AKI. The group with AKI presented with more DGF (42.1% versus 12.2%) and worse kidney function throughout the first six months after transplant. However, in the mid- and long-term periods, the kidney function at 12 months and survival of the graft at five and ten years were similar in both groups. The degree of AKI, according to the AKIN classification, did not interfere in the results.(31)

In 2013, the first successful kidney transplants that used organs from a donor with AKI undergoing dialysis were documented. The donor was 20 years old, had suffered a car accident, and progressed with oliguria, AKI, and the need for continued dialysis. The preimplantation biopsy revealed findings consistent with acute tubular necrosis, and both kidneys were implanted in patients aged 55 and 59 years, with cold ischemia times of about 12 and 18 hours, respectively. An initial less nephrotoxic immunosuppression regimen was chosen with cyclosporine, which is generally recommended when high-creatinine organs are used. The first patient progressed without DGF and the last creatinine level at follow-up was 0.95mg/dL; the second progressed with DGF and had two episodes of acute rejection, and the last creatinine level at follow-up was 1.38mg/dL.(30) This case report demonstrates that there is one more opportunity for expanding the pool of donors.

HOSPITAL ISRAELITA ALBERT EINSTEIN EXPERIENCE WITH THE USE OF DONORS WITH ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY

A cohort of 150 patients transplanted from deceased kidney donors at the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein Albert, between January 2008 and December 2011, was retrospectively analyzed. The objective was to evaluate the impact of the donor's terminal creatinine on DGF, days of DGF, days of hospitalization, kidney function of the recipient, and survival of patient and graft at the end of one year. Patients were classified as per the value of the donor's terminal creatinine: one group had a terminal creatinine level ≤1.5mg/dL and the other, creatinine >1.5mg/dL. Immunosuppression in this group consisted of induction with thymoglobulin and maintenance composed of tacrolimus, prednisone, and sodium mycophenolate. The analysis was also reproduced considering creatinine quartiles of the donor, and all results were similar.

The mean age of the donors was 40.6±14.7 years. Of the total 150 patients of the sample, 90 donors (60%) presented with serum creatinine levels ≤1.5mg/dL, and 60 (40%) presented with levels of serum creatinine >1.5mg/dL. The mean donor terminal creatinine was 1.6±1.1mg/dL, and the median was 1.3mg/dL (minimum of 0.37 and maximum of 8.8mg/dL). The following results were found.

Delayed graft function

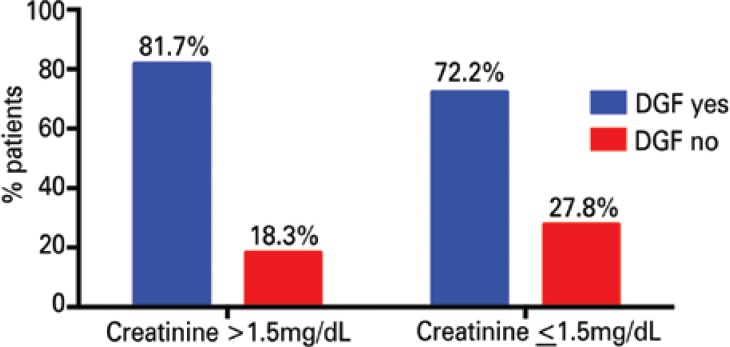

In this case series, 114/150 (76%) patients presented with DGF. Among the patients who had donor terminal creatinine levels >1.5mg/dL, 81.7% (49/60) presented with DGF, while in the group that presented with donor terminal creatinine <1.5mg/dL, 72.2% (65/90) of the patients presented with DGF. This difference was not statistically significant, with p=0.184 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Association between delayed graft function and donor creatinine.

The mean DGF days was 13.8±11.8 (median of 12 days; minimum of 2; maximum of 87 days). Considering only the patients who presented with DGF, there was no difference in the median DGF time when comparing the groups with donor terminal creatinine greater or lesser than 1.5mg/dL, with a median of 12 days (minimum of 3 and maximum of 87 for creatinine >1.5mg/dL; and a minimum of 2 and maximum of 56 for creatinine <1.5mg/dL) for both groups, with p=0.612.

Length of stay

The mean length of stay after the transplant was 24.2±16.9 days (median of 20 days; minimum of 5; maximum of 107). In the group with donor terminal creatinine ≤1.5mg/dL, the median length of stay was 18.5 days (minimum of 5 and maximum of 86 days), and in the group with donor terminal creatinine >1.5mg/dL, it was 21 days (minimum of 7 and maximum of 107 days), with no statistical difference between the two groups, with p=0.191.

Kidney function of the recipient: 1, 6, and 12 months after the transplant

The donor terminal creatinine was not associated with the creatinine values of the recipient throughout the first year (analysis made considering the donor creatinine both as a continuous and as categorical variable), with p<0.05 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association between creatinine of the donor and creatinine of the recipient at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Patient survival

In the group with donor terminal creatinine ≤1.5mg/dL, there were 3/90 (3.3%) deaths, resulting in a patient survival rate of 96.6% at the end of one year. In the group with donor terminal creatinine >1.5mg/dL, there were 2/60 deaths (3.3%), resulting in a patient survival rate of 96.6% at the end of one year. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups relative to patient survival (p=0.970) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patient survival.

Graft survival

In the group with donor terminal creatinine ≤1.5mg/dL, there was 1/90 (1.1%) graft loss, resulting in a graft survival rate of 98.9% at the end of one year. In the group with donor terminal creatinine >1.5mg/dL, there were 2/60 (3.3%) graft losses, resulting in a survival rate of 96.6% at the end of one year. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups as to survival of the graft (p=0.327) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Survival of the graft.

In this cohort of the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein with a sample of 150 patients, no losses were noted as to recipient outcomes using donors with terminal creatinine levels >1.5mg/dL. Although this was a univariate analysis, and other donor characteristics were not analyzed (standard or ECD) or the data regarding procurement and recipient – which could have influenced the result, it was possible to demonstrate with these data that donor terminal creatinine >1.5mg/dL did not impact on the DGF rate, DGF days, length of stay, function of the graft, survival of the graft, and survival of the patient. These data suggest that the high level of donor terminal creatinine cannot be a single criterion for selecting donors, since this elevation might be the result of some acute event, whether ischemic or of another nature along the procurement process, and be reversible.(6)

Considering all the studies mentioned here, most of them showed favorable results for mid-term periods when they used kidneys from standard donors with high levels of terminal creatinine. Although the acute kidney injury in the donor is associated with a higher rate of delayed graft function, survival of the graft/patient was similar to that of standard donors without acute kidney injury for mid- and long-term periods. Organs from donors with elevated terminal creatinine, whether standard or donors with expanded criteria, have a greater chance of being discarded.(1,6,25,26,31–34)

It is recommended that the selection of these donors be very strict; in other words, young donors be preferentially selected, with no history of hypertension, diabetes, preexisting kidney disease, or whose cause of death was not a cardiovascular event. In the standard donor, acute kidney injury represents, in most cases, a reversible acute clinical picture, while in the donors with expanded criteria, acute kidney injury may represent a chronic disease of the renal parenchyma; thus the importance of the biopsy and the parameters of the machine perfusion for decision-making at the time of organ supply.(25)

In the presence of elevated terminal creatinine, the donor's creatinine and creatinine clearance upon admission should also be investigated, since they are more important than terminal creatinine level (before the extraction), and have a greater relation with the baseline renal function of this individual than terminal creatinine. The evolution of creatinine should be evaluated, since evidence of improved renal function suggests that the organ is viable and that this recovery will continue after the transplant. Sometimes, the admission creatinine may be elevated and it is difficult to interpret the baseline renal function – showing the importance of joining other clinical and histological data, as well as, whenever possible, the machine perfusion parameters, such as intrarenal flow and intrarenal resistance.(25)

Chronic histological findings (interstitial fibrosis, vasculopathy, and glomerulosclerosis) in the donor, when accompanied by high creatinine levels, even in standard donors, are associated with worse outcomes(33) and with machine perfusion parameters; especially intrarenal resistance associates with a worse prognosis, and should, therefore be taken into consideration when selecting a donor without ideal criteria.(33)

CONCLUSION

Although most studies showed that there is a greater rate of delayed graft function with the use of these organs, the results of survival of graft and of patient after transplant are very similar to the results obtained with the use of standard donors. The clinical and morphological findings of the donor, the use of machine perfusion, and the analysis of its parameters, especially intrarenal resistance, are important support tools for decision-making at the time of supply of organs with kidney injury.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farney AC, Rogers J, Orlando G, al-Geizawi S, Buckley M, Farooq U, et al. Evolving experience using kidneys from deceased donors with terminal acute kidney injury. J Am Col Surg. 2013;216(4):645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.020. discussion 655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sesso RC, Lopes AA, Thomé FS, Lugon JR, Watanabe Y, dos Santos DR. Report of the Brazilian Chronic Dialysis Census 2012. J Bras Nefrol. 2014;36(1):48–53. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20140009. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Associação Brasileira de Transplantes de Órgãos Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes 2013 [Internet]. Ano XIX n3 (Jan-Set) 2013. Disponível em: http://www.abto.org.br/abtov03/default.aspx?mn=457&c=900&s=0.

- 5.São Paulo. Secretaria de Estado da Saúde do Estado de São Paulo . Sistema Estadual de Transplantes [Internet]. Taxa de mortalidade em lista de espera. São Paulo: Sistema Estadual de Transplantes; 2015. [[citado 2015 Jun 3]]. Disponível em: http://ctxses.saude.sp.gov.br/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuckerman JM, Singh RP, Farney AC, Rogers J, Stratta RJ. Single center experience transplanting kidneys from deceased donors with terminal acute renal failure. Surgery. 2009;146(4):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.036. discussion 694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Port FK, Bragg-Gresham JL, Metzger RA, Dykstra DM, Gillespie BW, Young EW, et al. Donor characteristics associated with reduced graft survival: an approach to expanding the pool of kidney donors. Transplantation. 2002;74(9):1281–1286. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojo AO. Expanded criteria donors: process and outcomes. Semin Dial. 2005;18(6):463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schold JD, Meier-Kriesche HU. Which renal transplant candidates should accept marginal kidneys in exchange for a shorter waiting time on dialysis? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(3):532–538. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks WH, Wagner D, Pearson TC, Orlowski JP, Nelson PW, McGowan JJ, et al. Organ donation and utilization, 1995-2004: entering the collaborative era. American journal of transplantation era. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5 Pt 2):1101–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domagala P, Kwiatkowski A, Perkowska-Ptasinska A, Wszola M, Panufnik L, Paczek L, et al. Assessment of kidneys procured from expanded criteria donors before transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(8):2966–2969. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munivenkatappa RB, Schweitzer EJ, Papadimitriou JC, Drachenberg CB, Thom KA, Perencevich EN, et al. The Maryland aggregate pathology index: a deceased donor kidney biopsy scoring system for predicting graft failure. A J Transplant. 2008;8(11):2316–2324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson CJ, Johnson RJ, Birch R, Collett D, Bradley JA. A simplified donor risk index for predicting outcome after deceased donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;93(3):314–318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823f14d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajwa M, Cho YW, Pham PT, Shah T, Danovitch G, Wilkinson A, et al. Donor biopsy and kidney transplant outcomes: an analysis using the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) database. Transplantation. 2007;84(11):1399–1405. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000282868.86529.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayler LK, Mohanka R, Basu A, Shapiro R, Randhawa PS. Correlation of histologic findings on preimplant biopsy with kidney graft survival. Transplant Int. 2008;21(9):892–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tso PL, Dar WA, Henry ML. With respect to elderly patients: finding kidneys in the context of new allocation concepts. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(5):1091–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockfield SM, Moore RB, Todd G, Solez K, Gourishankar S. The prognostic utility of deceased donor implantation biopsy in determining function and graft survival after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89(5):559–566. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ca7e9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woestenburg AT, Verpooten GA, Ysebaert DK, Van Marck EA, Verbeelen D, Bosmans JL. Fibrous intimal thickening at implantation adversely affects long-term kidney allograft function. Transplantation. 2009;87(1):72–78. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818bbe06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin NC, Yang AH, King KL, Wu TH, Yang WC, Loong CC. Results of kidney transplantation from high-terminal creatinine donors and the role of time-zero biopsy. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(9):3382–3386. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor MJ, Baicu SC. Current state of hypothermic machine perfusion preservation of organs: The clinical perspective. Cryobiology. 2010;60(3 Suppl):S20–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.10.006. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moers C, Smits JM, Maathuis MH, Treckmann J, van Gelder F, Napieralski BP, et al. Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(1):7–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moers C, Pirenne J, Paul A, Ploeg RJ, Machine Preservation Trial Study Group Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):770–771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1111038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao B, Liu S, Liu H, Cheng D, Cheng Y, Liu Y. Hypothermic machine perfusion reduces delayed graft function and improves one-year graft survival of kidneys from expanded criteria donors: a meta-analysis. PloS One. 2013;8(12): doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081826. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckerman JM, Singh RP, Farney AC, Rogers J, Hines MH, Stratta RJ. Successful kidney transplantation from a donation after cardiac death donor with acute renal failure and bowel infarction using extracorporeal support. Transpl Int. 2009;22(8):798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kayler LK, Garzon P, Magliocca J, Fujita S, Kim RD, Hemming AW, et al. Outcomes and utilization of kidneys from deceased donors with acute kidney injury. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(2):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deroure B, Kamar N, Depreneuf H, Jacquet A, Francois H, Charpentier B, et al. Expanding the criteria of renal kidneys for transplantation: use of donors with acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(6):1980–1986. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein R, Galante NZ, de Sandes-Freitas TV, de Franco MF, Tedesco-Silva H, Medina-Pestana JO. Transplantation with kidneys retrieved from deceased donors with acute renal failure. Transplantation. 2013;95(4):611–616. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318279153c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenstein SM, Moore N, McDonough P, Schechner R, Tellis V. Excellent outcome using “impaired” standard criteria donors with elevated serum creatinine. Clin Transplant. 2008;22(5):630–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2010 data report. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(Suppl 1):1–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bacak-Kocman I, Peric M, Kastelan Z, Kes P, Mesar I, Basic-Jukic N. First documented case of successful kidney transplantation from a donor with acute renal failure treated with dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(5):1523–1526. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MH, Jeong EG, Chang JY, Kim Y, Kim JI, Moon IS, et al. Clinical outcome of kidney transplantation from deceased donors with acute kidney injury by Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria. J Crit Care. 2014;29(3):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan C, Martin A, Shapiro R, Randhawa PS, Kayler LK. Outcomes after transplantation of deceased-donor kidneys with rising serum creatinine. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(5):1288–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugarte R, Kraus E, Montgomery RA, Burdick JF, Ratner L, Haas M, et al. Excellent outcomes after transplantation of deceased donor kidneys with high terminal creatinine and mild pathologic lesions. Transplantation. 2005;80(6):794–800. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000173801.33878.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekeel KL, Moss AA, Mulligan DC, Chakkera HA, Hamawi K, Mazur MJ, et al. Deceased donor kidney transplantation from donors with acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis. Am J Transplant. 2009 Jul;9(7):1666–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]