Abstract

This study investigated whether having friends who engaged in more prosocial than antisocial behaviors buffered the associations between family-of-origin aggression and later victimization. Adolescent participants (N=125) and their parents reported on different types of family aggression in early adolescence. Approximately 5 years later, adolescents reported on their victimization experiences with dating partners and friends, and their friends’ prosocial and antisocial behaviors. Only father-to-child aggression was significantly associated with dating and friend victimization, with stronger risk for females’ dating victimization. Moreover, having friends who engaged in more prosocial than antisocial behaviors had both a direct inverse relationship with dating partner victimization. This also buffered the risk for dating victimization associated with father-daughter aggression. Findings suggest that greater attention be paid to the father-daughter relationship and to the importance of having friends who engage in prosocial behaviors in the prevention of adolescents’ victimization.

Keywords: family aggression, friend victimization, dating victimization, prosocial friends, father-daughter relationship

Adolescents report high rates of victimization in dating relationships (e.g., Vezina & Hebert, 2007) and in relationships with friends and peers (e.g., Nansel et al., 2001). National prevalence estimates indicate that 40–60% of high school and college students report experiencing physical victimization, and 80–90% report psychological victimization by dating partners (Halpern, Oslak, Young, Martin, & Kupper, 2001; White & Koss, 1991); whereas, 17–20% report physical or psychological victimization from peers (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). Victimization experiences are, in turn, associated with adverse mental and physical health consequences, such as increased suicide risk, internalizing symptoms, and substance use (Evans, Marte, Betts, & Silliman, 2001; Reijntjes et al., 2010; Swahn et al., 2008; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006).

Though exposure to family aggression frequently emerges as a risk factor for later victimization by dating partners (Stith et al., 2000) and friends (Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001), some studies do not find these associations (e.g., Johnson & Ferraro, 2000). Moreover, even in studies with significant associations, a notable number of participants are resilient to the link between family-of-origin aggression and later victimization from dating partners and friends. This study aims to better understand the links between family aggression and dating and friend victimization by first considering whether type of family violence exposure is a distinguishing factor. Despite the fact that parent-to-parent aggression and parent-to-child aggression tend to be overlapping risks (Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl, & Moylan, 2008), they typically are examined in separate studies; thus, little is known about whether one type of parental aggression or whether the combination of parent-to-parent and parent-to-child aggression together is more risky for later dating or friend victimization. Second, because adolescence is a time of increasing interest and autonomy in developing affiliations with peers, it is important to assess who is selected as friends: Is the continuity of victimization affected by whether those who are selected as friends engage primarily in prosocial or deviant behavior? Prior longitudinal work suggests that youth who are exposed to family aggression grow up to affiliate with deviant or antisocial friends, which increases the likelihood of subsequent romantic partner violence and peer victimization (Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Ehrensaft et al., 2003). The present study extends what is known about the role of friends in trajectories of risk by testing whether affiliating with friends who engage in more prosocial than antisocial behaviors may protect against the risk of victimization by dating partners and friends in adolescence.

Family Aggression and Victimization

Studies have consistently found that individuals with a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse are 2 to 4 times more likely to experience later physical, sexual, or psychological victimization from dating partners compared to those without such histories (Cloitre et al., 1996; Coid et al., 2001; Gover, Kaukinen, & Fox, 2008; Schaaf & McCanne, 1998). Witnessing violence between parents also has been associated with later victimization from dating partners (Arriaga & Foshee, 2004; Stith et al., 2000). Similarly, parent-to-child aggression, harsh parenting, parental hostility, and maternal over control all have consistently been associated with higher levels of peer victimization (Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, Ijzendoor, & Crick, 2011; Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001; Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997).

Within families, it is unclear whether aggression perpetrated by mothers and fathers may have differential risks for females and males in the risk for later victimization. Mothers and fathers might differentially influence gender-specific relationship schemas for adolescent dating relationships, as well as gender norms for peer relationships (Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001), although findings have been mixed. For example, one study showed that fathers’ physical abuse, compared to mothers’ abuse, was more strongly associated with girls’ sexual victimization in adolescence (Rich, Gidycz, Warkentin, Loh, & Weiland, 2005). Other studies suggest that mothers, compared to fathers, have a more potent role in later victimization from peers (Baldry, 2003; Hendy et al., 2003; Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997). Further clarification is needed, especially given that prior studies have typically relied on retrospective reports from single reporters, which may underestimate family aggression exposure (Margolin, Vickerman, Oliver, & Gordis, 2010).

Affiliation with Prosocial and Antisocial Friends as Moderators

As peers begin to play an increasingly strong role in influencing attitudes and behaviors (Steinberg, 2008), they may serve as risk or protective factors in an adolescent’s likelihood of experiencing dating and friend victimization. Prior work has identified prospective associations between exposure to family aggression and affiliation with deviant peers (Ehrensaft et al., 2003). Adolescents from aggressive families are likely to develop hostile ways of relating to others and may gravitate towards aggressive and antisocial friends, who are more likely to victimize them (Güroğlu, Van Lieshout, Haselager, & Scholte, 2007). They may also espouse violent attitudes regarding dating relationships (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Feiring & Furman, 2000). Indeed, greater exposure to antisocial friends who engage in risky behaviors, substance use, and risky sex have been associated with increased risk for dating victimization, particularly given that adolescents may choose their dating partners from among an antisocial peer group (Cook, Buehler, & Fletcher, 2012). Lansford, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, and Bates (2003) also found that antisocial friends strengthened the association between harsh parenting and negative outcomes, suggesting that antisocial peers may amplify risks associated with exposure to family aggression.

In contrast, very few studies, to our knowledge, have examined the role of prosocial friends–or those who engage in community service, get good grades, and are liked by teachers– in buffering against the risk of victimization. Garrido and Taussig (2013) found that within a small sample of adolescents who were removed from their homes due to maltreatment, prosocial peers moderated the association between parent-to-parent aggression and later dating aggression, but not victimization. Further, one study found that affiliation with prosocial friends was protective against perpetration of violent behavior (Prinstein, Boergers, & Spirito, 2000). Further work is needed in this area, especially given that social development models highlight the role of prosocial friends in promoting resilient outcomes (Herrenkohl et al., 2008).

Though prior studies typically have assessed either antisocial friends or prosocial friends, it is very likely that adolescents are not quite that unidimensional in their friendships. Rather than categorizing friends as one or the other, it may be more accurate to conceptualize friends as engaging in both antisocial and prosocial behaviors—but in different proportions. Towards that aim, the present study examines the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors as a protective factor against the risk of both dating and friend victimization. That is, friends who engage in a higher proportion of prosocial than antisocial behaviors may be protective, whereas friends who engage equally in both prosocial and antisocial behaviors or engage in fewer prosocial than antisocial behaviors may be more risky. In terms of buffering the risk of victimization from parents to peers, affiliating with friends who engage in a higher proportion of prosocial than antisocial behaviors may serve to challenge expectations for aggressive behavior within relationships.

Gender Differences in Victimization

Findings on gender differences in rates of victimization have been mixed, with some studies finding higher rates among females, and still others reporting higher rates among males (e.g., Archer, 2004). It is also unclear whether there are gender differences in predictors of victimization (O’Keefe, 1998; O’Leary, Malone, & Tyree, 1994). A meta-analysis found that females in particular might be at increased risk for dating victimization following exposure to family aggression (Stith et al., 2000). The present study further explores the role of gender as a moderator in the interactions between family and friend influences on victimization.

Victimization in Late Adolescence

Despite the accumulating evidence that victimization occurs widely and leads to a host of negative outcomes among adolescents, most prior work has focused on adolescents prior to the age of 17 (e.g., Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010) or on college samples of young adults. Few studies have assessed victimization among a community sample of individuals between the ages of 17 to 21, referred to as late adolescents (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008). Though rates of victimization tend to decline from high school to college, late adolescents still report high rates of dating victimization (Hines & Saudino, 2003). Because of the particularly high rates of sexual and physical victimization during this developmental period (Chan, Straus, Brownridge, Tiwari, & Leung, 2008; Halpern, Spriggs, Martin, & Kupper, 2009; Rich et al., 2005), it is important to identify contributing factors.

Present Study

The first goal of the present study is to investigate direct associations between different types of family aggression in early adolescence and victimization from dating partners and friends in late adolescence. Total family aggression along with four separate types of family aggression will be tested: father-to-child, mother-to-child, father-to-mother and mother-to-father. We hypothesize that family aggression will be associated with victimization by dating partners and friends in late adolescence (Hypothesis 1) and do not have differential predictions based on type of family aggression. The second aim involving the protective influences of prosocial-to-antisocial friend behavior tests two hypotheses: (a) that affiliating with friends who engage in more prosocial than antisocial behaviors has a direct, inverse relationship with victimization from dating partners and friends (Hypothesis 2); and (b) that the proportion of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors buffers the association between different types of family aggression and victimization from dating partners and friends (Hypothesis 3). Lastly, gender is investigated through exploratory analyses as a possible moderator of the association between family aggression and victimization, as well a moderator in the associations between family aggression, friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior, and victimization.

Methods

Overview

Participants for the present study include adolescents and their parents who were recruited as part of a two-cohort longitudinal, multi-wave research study examining the effects of family conflict on parent and child outcomes. The two cohorts were recruited in identical ways and went through the identical procedures in the present study (see Margolin, Vickerman, Oliver & Gordis, 2010, for more details). Inclusion criteria were that a) families included two parents and at least one child; b) families lived together for at least the last 3 years; and c) all participants were able to read and speak English. Children in the first cohort were recruited at age 9–10 when they began the study and the children in the second cohort, designed to match the first cohort, were in middle school when they began the study approximately three years later.

The present study includes data from two time points that were spaced approximately 5 years apart. At the first time point, adolescents and their parents reported on family aggression experienced within the home. At the second time point, adolescents reported on their victimization experiences, as well as on their friends’ prosocial and antisocial behaviors. All data were collected in computer-administered questionnaires as part of a larger laboratory procedure. Families were compensated for their time and effort in each time point. The study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave written consent (assent by the youth) before participating in the study.

Participants

A total of 125 adolescent participants (58 females, 67 males; 85 from cohort 1 and 40 from cohort 2) are included in the present study. Inclusion into the present study required that adolescents and their parents complete questionnaires assessing family aggression at the first time point and that adolescents complete a measure of victimization at the second time point. Out of a 170 who were eligible at the first time point, 125 participated at the second time point. A comparison of those who participated in the first time point but were not included in the 125 here indicated that there were no differences in gender, race, ethnicity, adolescent ages, family income, or level of family aggression. Analyses comparing differences between participants from cohort 1 and 2 on the same variables indicated that adolescents from Cohort 2 (M = 13.04) were older than adolescents from Cohort 1 at the first time point (M = 12.49), t(114)= −3.90, p < .001.

Adolescents were, on average, 12.68 years old (SD = .76) at the first time point and 18.19 years old (SD = 1.11) at the second time point. The sample is ethnically and racially diverse, with 35.2% identifying as Hispanic/Latino; self-identified race was 5.6% Asian/Pacific Islander, 17.6% Black/African American, 57.6% Caucasian, and 19.2% as multiple ethnicities. The median combined income of families in our study was $80,000 (M = $90,497, SD = $54,956). Reports of family income indicated that 21% reported incomes <$50,000; 40% reported incomes between $50,000 and $100,000, and 33.9% reported incomes greater than >$100,000. The total family income of approximately 10% of the participating families was below the national poverty level.

Measures

Parent-to-Child Aggression

Adolescents and their parents reported on parent-to-child aggression at the first time point using a modified version of the Parent Child Conflict measure (PCC; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). All participants answered the same 6 items: 4 items of psychological aggression (e.g., “Called you dumb or lazy or some other name like that”), as well as 2 items of physical aggression (e.g., “Slapped you on the hand, arm, or leg”). Adolescents completed one set of items for their mother and another identical set for their father. Parents reported on their own behavior towards their child (e.g. “I called my child dumb or lazy”). Respondents reported the frequency of each item during the last year on a 7-point scale that was rescaled to 4 points (0 = never, 1 = once; 2 = 2–5 times; 3 = >6 times). Given that people tend to under-report violence and conflict experiences (Margolin et al., 2010), the maximum reported score from each reporter (adolescent, mother, father) was calculated for each item. Then the scores were summed to yield a separate measure of mother-to-child aggression and a measure of father-to-child aggression, such that higher scores indicated greater aggression. Internal consistency was acceptable in the measure of mother-to-child aggression (α = .77) and father-to-child aggression (α = .78).

Parent-to-Parent Aggression

Adolescents reported on parent-to-parent aggression at the first time point through 9 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) that represented 5 items of psychological aggression (e.g., “Insulted or swore at the other person”) and 4 items of physical aggression (e.g., “Slapped the other person”). They answered each question twice, once for mother-to-father aggression and once for father-to-mother aggression and reported the frequency to which they witnessed parent-to-parent aggression in the last year on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = a lot). Parents reported on the same 9 items from the Domestic Conflict Inventory, where some items were worded slightly differently (DCI; Margolin, John, & Foo, 1998). Parents answered each item twice, once for themselves e.g., “I pushed, grabbed, or shoved my spouse”, and once for their partner e.g., “My spouse pushed, grabbed, or shoved me”. Parents were asked to indicate the frequency to which they or their spouse perpetrated aggression in the last year on a 6-point scale that was rescaled to 4 points (0 = never, 1 = once; 2 = 2–5 times; 3 = >6 times). Second, the maximum reported score from each reporter (adolescent, mother, father) was calculated for each item. The items were summed to yield a separate measure of mother-to-father aggression and a measure of father-to-mother aggression, such that higher scores indicated greater aggression. Internal consistency was acceptable in the measure of mother-to-father aggression (α = .76) and father-to-mother aggression (α = .74). Lastly, total family aggression was calculated by summing the four types of family aggression variables (father-to-child, mother-to-child, father-to-mother, mother-to-father).

Victimization

The assessment of victimization through the How Friends Treat Each Other scale (HFTEO, Bennett et al., 2011) included 9 physical (e.g., “slapped me”), 26 psychological (e.g., “insulted me with put-downs”), 7 sexual (e.g., “touched me sexually when I didn’t want it”) and 21 electronic items of victimization (e.g., “put a picture of me on a website that I didn’t want there”); some of these items were adapted from the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (Wolfe et al., 2001). Respondents indicated the frequency to which they experienced victimization events during the past year on a 5-point scale (0 = never happened to 4 = happened more than 10 times). Respondents answered each question twice, once for each type of perpetrator: “any boyfriend/girlfriend” or “any friend”. In the instance that someone fell into more than one category (e.g., was a friend and now is a boyfriend/girlfriend), participants were instructed to rate individuals in the category that best applied. Mean scores were calculated for each of the four types of victimization separately for dating partner and friend victimization. Satisfactory internal consistency was found for each type of dating victimization (α = .90, .95, .87 and .88 for physical, psychological, sexual and electronic victimization) and friend victimization (α = .75, .91, .66 and .74 for physical, psychological, sexual and electronic victimization). In order to limit the total number of analyses, we calculated one score for dating victimization and one for friend victimization, based on the average across all items. Internal consistency was high (α = .97 for victimization by dating partner and .93 for victimization by friend).

Friends’ Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior

Adolescents reported on how many of their close friends engaged in prosocial (13 items, e.g., “have done volunteer work”) and antisocial behaviors (17 items, e.g., “have cheated on school tests”) at the second time point using a modified version of the Peer Behavior Inventory (PBI, Prinstein, Boergers, & Spirito, 2001). The original 19-item scale was expanded to 33 items to include additional items of risky behaviors, as well as additional items of prosocial behaviors. One item assessing suicidality and another item that overlapped with victimization were both removed for the purposes of the present study. Respondents first were asked to think about their closest friends and to list the first initial (of up to) 10 close friends. They next reported how many of their friends engaged in these behaviors on a 5-point scale (0 = none; 1= one; 2 = a few; 3 = more than half; and 4 = almost all). Internal consistency was high for both prosocial items (α = .85) and antisocial items (α = .90). Similar to the original PBI, where deviant and prosocial behaviors were separate factors, prosocial and antisocial scores here were not correlated (r = .03 for males and .07 for females), suggesting that prosocial versus antisocial friends are not simply opposite end-points of one continuum. We calculated the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors on the prosocial and antisocial means, with higher scores indicating a greater proportion of friends engaging in prosocial than antisocial behaviors. This ratio does not specifically indicate the number of friends who engage in certain behaviors, but serves as an index of affiliation with prosocial compared to antisocial friends in the participant’s social context. On average, participants reported that their friends engaged in over twice as many prosocial than antisocial behaviors, although the prosocial-to-antisocial ratio ranged from .63 to 4.69. As a measure of discriminant validity, prosocial behaviors, antisocial behaviors, and the prosocial-to-antisocial ratio were correlated with a measure of peer social support, as measured by the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Green, 1987). Prosocial behaviors modestly correlated with social support (r =.32, p <.001), whereas antisocial behaviors and the ratio of prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors were positively, but not significantly, correlated with social support (r =.03, ns; r =.12, ns, respectively).

Demographic variables

Adolescents and their parents additionally reported their age, gender, family income, race and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Our descriptive analyses included (a) ANOVAs for the four types of victimization (physical, psychological, sexual, and electronic) to test whether males and females differed in the amount of victimization they received from dating partners vs. friends; (b) T-tests to test whether levels of family aggression differed significantly between mothers and fathers; and (c) correlations among all study variables. We tested Hypotheses 1–3 through separate linear regression analyses for each type of family aggression, as well as total family aggression. To test Hypothesis 1 regarding the associations between family aggression and later victimization, as well as interactions with gender, we created interaction terms between gender and each of the five family aggression variables. All continuous variables were standardized prior to computing interaction terms and conducting regression analyses. Main effect and interaction terms for gender and family aggression variables were included in interaction models. Significant interactions were evaluated based on recommendations by Aiken and West (1991). To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we ran linear regressions that included family aggression, friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior and gender, as well as each of the respective 2-way and 3-way interaction terms. Specifically for Hypothesis 2, we investigated the main effects of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior and the 2-way interaction with gender. For Hypothesis 3, we examined the 3-way interaction term that included family aggression, prosocial-to-antisocial behavior and gender.

As is common with studies on adolescent dating aggression, some participants may not have been in serious dating relationships. We ran all analyses excluding the subset of those who indicated that they had not dated in the past year (n = 15) and found that the direction of the analyses did not change. Subsequently, we included the full sample (n = 125) in all analyses to maximize the number of people who experienced both dating and friend victimization and to account for participants who may have experienced dating victimization outside the bounds of an exclusive dating relationship, as done in prior studies of dating victimization (Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Results indicated that 59.2% of participants reported physical victimization by a dating partner or friend at least once, 95.8% reported psychological victimization, 42.5% sexual and 85% electronic. Further, 63.2% of participants reported at least one victimization experience from dating partners and 87.2% reported at least one victimization experience from friends. Table 1 presents mean scores for males and females for each of the four victimization types by dating partners and friends and also presents results of four 2 (gender) X 2 (dating partner vs. friend) ANOVAs that tested differences between males and females by dating partners and friends for each type of victimization. Overall, both males and females reported more sexual victimization from dating partners than from friends. Females reported more electronic victimization than males. For physical, psychological and electronic victimization, the interaction between perpetrator and gender indicated that males reported more frequent victimization by friends, whereas females reported more frequent victimization by dating partners.

Table 1.

Males’ and females’ mean victimization scores from dating partners and friends within the past year

| Types of Victimization | Males (n = 67) | Females (n = 58) | F Gender | F Perpetrator | F Gender X Perpetrator | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Dating Partner | Friend | Dating Partner | Friend | ||||

| Physical | .08 (.23) | .21 (.31) | .19 (.51) | .10 (.46) | .00 | .23 | 7.10* |

| Psychological | .23 (.33) | .37 (.40) | .51 (.78) | .36 (.26) | 3.57 | .00 | 6.90* |

| Sexual | .10 (.24) | .07 (.17) | .16 (.51) | .04 (.10) | .06 | 5.22* | .23 |

| taElectronic | .08 (.13) | .13 (.18) | .22 (.39) | .14 (.16) | 6.05* | .36 | 5.65* |

Note. SDs are in parentheses.

p < .05

Analyses comparing differences between mothers’ and fathers’ aggression indicated that mothers had higher levels of overall parent-to-child aggression (M = 5.66, SD = 3.52, t(124) = 2.80, p = .01) compared to fathers (M = 4.47, SD = 3.65). More specifically, mothers exhibited higher psychological aggression to their child: for mother-to-child psychological aggression, M = 4.66 (SD = 2.65) and for father-to-child psychological aggression, M = 3.68 (SD = 2.71), t(124) = 4.13, p <.001). Mothers and fathers did not differ in level of physical aggression to the child. Mothers also exhibited higher levels of overall inter-parental aggression (M = 4.17, SD = 3.44) compared to fathers (M = 3.46, SD = 3.25). More specifically, mothers also exhibited higher levels of psychological inter-parental aggression: for mother-to-father psychological aggression, M = 3.58, (SD = 2.47) and for father-to-mother psychological aggression, M = 3.09 (SD = 2.45), t(124) = 2.76, p = .01. No differences emerged between mothers and fathers for physical aggression towards each other.

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics among all study variables for males and females. Although the four types of family aggression were correlated with each other, only father-to-child aggression was significantly correlated with victimization, specifically with females’ dating partner and friend victimization. The ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior was inversely related to dating partner victimization for both females and males. In addition, for females but not males, dating partner victimization and friend victimization were correlated.

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptive statistics for all study variables for males (above the diagonal) and for females (below the diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total Family aggression | - | .67** | .75** | .76** | .75** | .08 | −.28* | .05 | .22 | 17.13 | 9.67 |

| 2. Father-to-Child Aggression | .74** | - | .48** | .32** | .13 | .15 | −.10 | .03 | .20 | 4.64 | 3.55 |

| 3. Mother-to-Child Aggression | .76** | .55** | - | .30* | .39** | −.09 | −.26* | .03 | .22 | 5.46 | 3.28 |

| 4. Father-to-Mother Aggression | .77** | .35** | .35** | - | .67** | .07 | −.22 | −.02 | .12 | 3.18 | 2.83 |

| 5. Mother-to-Father Aggression | .72* | .25 | .34** | .63** | - | .08 | −.24 | .08 | .09 | 3.85 | 3.62 |

| 6. Family Incomea | .01 | −.11 | .07 | .03 | .05 | - | .11 | −.25* | .22 | 8.83 | 5.48 |

| 7. Friends’ Prosocial/ Antisocial Behaviors | −.05 | −.25 | −.08 | .14 | .06 | .09 | − | −.30* | −.16 | 2.01 | .87 |

| 8. Dating Partner Victimizationb | .20 | .41** | .14 | −.01 | .04 | −.12 | −.52** | − | .19 | .13 | .19 |

| 9. Friend Victimization | .15 | .32* | .21 | −.01 | −.10 | −.07 | −.22 | .36** | - | .22 | .23 |

| M | 18.48 | 4.28 | 5.90 | 3.78 | 4.53 | 9.46 | 2.25 | .28 | .20 | ||

| SD | 10.81 | 3.78 | 3.80 | 3.67 | 3.21 | 5.45 | .73 | .41 | .24 |

Note.

Income represented here as $10,000.

Denotes significant mean differences between males and females

p < .05,

p < .001

Association between Family Aggression and Victimization with Gender as a Moderator

Table 3 presents a series of five linear regression analyses that tested the main effects and the interaction for total family aggression, as well as for each type of family aggression and gender (Hypothesis 1). Family income was first included as a covariate but was later dropped from analyses because it did not change the direction or strength of the associations. Main effects showed that father-to-child aggression was significantly associated with both dating partner and friend victimization. In addition, gender was a significant moderator of the association between father-to-child aggression and dating partner victimization. When the slope of the interaction was decomposed (Aiken & West, 1991), a significant positive association emerged between father-to-child aggression and dating partner victimization for females (b = .03, p < .001) but not for males (b = .00, ns).

Table 3.

Regression analyses of family aggression variables predicting victimization by dating partners and friends

| Dating Partner Victimization | Friend Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Total Family Aggression | .007 | .004 | .239 | .003 | .003 | .147 |

| Gender | −.144 | .055 | −.227* | .023 | .042 | .048 |

| Total Family Aggression x Gender | −.007 | .005 | .229 | .002 | .004 | .053 |

| Father-to-Child Aggression | .044 | .010 | .504** | .021 | .008 | .315* |

| Gender | −.159 | .052 | −.250* | .011 | .042 | .022 |

| Father-to-Child x Gender | −.042 | .014 | −.343* | −.007 | .011 | −.625 |

| Mother-to-Child Aggression | .015 | .011 | .160 | .013 | .008 | .197 |

| Gender | −.147 | .056 | −.230* | .023 | .042 | .049 |

| Mother-to-Child x Gender | −.013 | .016 | −.097 | .002 | .012 | .021 |

| Father-to-Mother Aggression | −.001 | .011 | −.009 | .000 | .009 | .041 |

| Gender | −.151 | .056 | −.237* | .019 | .043 | .041 |

| Father-to-Mother x Gender | −.001 | .018 | −.003 | .010 | .014 | .086 |

| Mother-to-Father Aggression | .004 | .013 | .048 | −.008 | .010 | −.112 |

| Gender | −.147 | .056 | −.232* | .016 | .043 | .034 |

| Mother-to-Father x Gender | .000 | .017 | −.003 | .014 | .013 | .150 |

p < .05,

p < .001

No other significant main effects for family aggression or gender interactions emerged for total family aggression, mother-to-child aggression, father-to-mother aggression or mother-to- father aggression. As anticipated by the correlations, gender consistently showed main effects for dating partner victimization.

Friends’ Prosocial-to-Antisocial Behavior as a Moderator of the Association between Family Aggression and Victimization

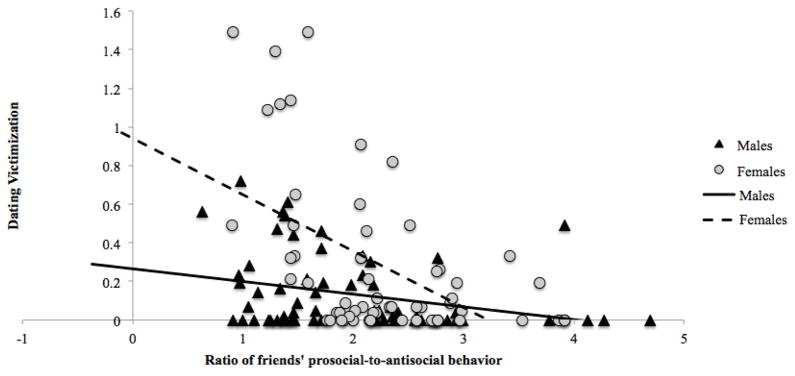

Table 4 presents our tests of Hypotheses 2 and 3, in which we examined 2-way and 3-way interactions in analyses that included family aggression, friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior, and gender. Support for Hypothesis 2—that friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior would have a direct inverse relationship on victimization—is evidenced in the analyses on dating partner victimization across all the analyses. This protective factor was particularly significant for females, as shown by the significant interactions between the ratio of prosocial-to-antisocial behavior and gender. The scatterplot in Figure 1 displays the bi-variate relationship between the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors and dating partner victimization for females and males, with a significant inverse relationship for females (b = −.29) and males (b = −.07). In contrast, friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior was not a protective factor for victimization by friends.

Table 4.

Regression analyses investigating prosocial-to-antisocial friend ratio and gender as moderators of the association between family aggression and dating partner and friend victimization

| Dating Partner Victimization | Friend Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Total family aggression | .005 | .003 | .227* | .003 | .002 | .155 |

| Gender | −.192 | .052 | −.302** | .012 | .045 | .026 |

| Prosocial/antisocial | −.279 | .050 | −.708** | −.071 | .044 | −.241 |

| Total family aggression x gender | −.008 | .005 | −.177 | .001 | .005 | .042 |

| Prosocial/antisocial x gender | .206 | .068 | .410* | .046 | .059 | .124 |

| Total family aggression x prosocial/antisocial | −.006 | .005 | −.169 | .000 | .004 | −.010 |

| Total family aggression x gender x prosocial/antisocial | .006 | .007 | .114 | .002 | .006 | .041 |

| Father-to-child aggression | .034 | .010 | .394** | .020 | .008 | .308* |

| Gender | −.175 | .048 | −.275** | .010 | .042 | .022 |

| Prosocial/antisocial | −.246 | .049 | −.625** | −.046 | .043 | −.157 |

| Father-to-child aggression x gender | −.030 | .014 | −.240* | −.012 | .012 | −.131 |

| Prosocial/antisocial x gender | .191 | .063 | .380* | .003 | .055 | −.007 |

| Father-to-child aggression x prosocial/antisocial | −.025 | .012 | −.226* | −.020 | .010 | −.240 |

| Father-to-child aggression x gender x prosocial/antisocial | .037 | .018 | .237* | .009 | .016 | .075 |

| Mother-to-child aggression | .045 | .032 | .493 | .027 | .027 | .396 |

| Gender | −.194 | .052 | −.305** | .009 | .044 | .020 |

| Prosocial/antisocial | −.282 | .051 | −.716** | −.066 | .043 | −.225 |

| Mother-to-child aggression x gender | −.020 | .016 | −.149 | −.002 | .013 | −.018 |

| Prosocial/antisocial x gender | .205 | .069 | .408* | .031 | .058 | .084 |

| Mother-to-child aggression x prosocial/antisocial | −.014 | .012 | −.366 | −.006 | .010 | −.206 |

| Mother-to-child aggression x gender x prosocial/antisocial | 0.009 | .018 | −.061 | .003 | .016 | .029 |

| Father-to-mother aggression | .015 | .043 | .153 | −.057 | .037 | −.782 |

| Gender | −.672 | .151 | −1.06** | −.102 | .128 | −.216 |

| Prosocial/antisocial | −.296 | .052 | −.753** | −.082 | .044 | −.281 |

| Father-to-mother aggression x gender | −.016 | .051 | −.104 | .041 | .043 | .359 |

| Prosocial/antisocial x gender | .223 | .067 | .830* | .059 | .057 | .293 |

| Father-to-mother aggression x prosocial/antisocial | −.003 | .017 | −.074 | .024 | .015 | .770 |

| Father-to-mother aggression x gender x prosocial/antisocial | .000 | .023 | .001 | −.011 | .019 | −.189 |

| Mother-to-father aggression | .015 | .034 | .157 | −.041 | .029 | −.593 |

| Gender | −.673 | .151 | −1.06** | −.106 | .128 | −.223 |

| Prosocial/antisocial | −.293 | .052 | −.745** | −.080 | .044 | −.274 |

| Mother-to-father aggression x gender | −.011 | .042 | −.087 | .021 | .035 | .236 |

| Prosocial/antisocial x gender | .225 | .068 | .838* | .059 | .058 | .294 |

| Mother-to-father aggression x prosocial/antisocial | −.003 | .015 | −.059 | .016 | .013 | .476 |

| Mother-to-father aggression x gender x prosocial/antisocial | .000 | .021 | .007 | −.002 | .018 | −.031 |

Note. Prosocial/antisocial = the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior.

p < .05,

p < .001

Figure 1.

Female and male dating victimization as a function of the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior. The regression lines represent the estimated linear change in dating victimization per unit change in the prosocial-to-antisocial ratio.

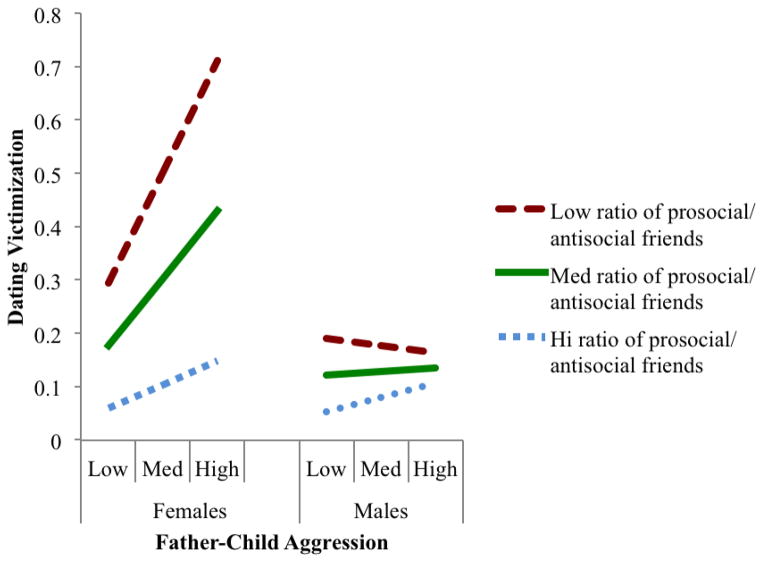

Data on the buffering effect of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior (Hypothesis 3) is found in the association between father-to-child aggression and dating partner victimization, where there was a significant 2-way interaction between father-to-child aggression and friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior, as well as a significant 3-way interaction that also included gender. Figure 2 displays the plot of the significant 3-way interaction, where we evaluated the simple slopes at low (1 SD below the mean), medium (mean), and high (1 SD above the mean) levels for father-to-child aggression and friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior for females and males. For females, the positive association between father-to-child aggression and victimization by dating partner was significant for those with low (b = .04, p < .001) and medium ratios of prosocial-to-antisocial friend behavior (b = .03, p < .001) but not for those with a high ratio of prosocial-to-antisocial friend behavior (b = .01, ns). Among males, the positive association between father-to-child aggression and victimization by dating partner was unrelated to their friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors (b’s = −.00–.01, ns). In addition, the moderating effect for friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior only emerged in the analysis of father-to-child aggression.

Figure 2.

The ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior as a moderator of the interaction of gender by father-to-child aggression, reported separately for females and males. Slopes are significant for females at a low (b = .04, p < .001) and medium ratio of prosocial/antisocial friends (b = .03, p < .001) but not at a high ratio of prosocial/antisocial friends (b = .01, ns). Slopes are not significant for males (b’s = .00 .004, ns).

Discussion

This study investigated both family and friend influences in the trajectory to late adolescent victimization by dating partners and friends. In partial support of Hypothesis 1 on the influence of family aggression, we found that only father-to-child aggression, among all four types of family aggression, was associated with later friend victimization for both males and females. Father-to-child aggression also was significantly associated with females’ but not males’ later dating victimization. In partial support of Hypothesis 2, we found that the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior had protective effects against females’, but not males’, dating partner victimization regardless of family violence history. Relatedly, in support of Hypothesis 3, the ratio of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behavior buffered the association between father-to-child aggression and females’ risk for dating victimization. Specifically, females with a high prosocial-to-antisocial friend ratio did not show the association between father-to-child aggression and dating victimization that was evidenced in females with low and medium prosocial-to-antisocial friend ratios. These data highlight both the relevance of fathers’ adverse treatment of their daughters and also the ameliorating influences of prosocial friendships in daughters’ later dating relationships.

The Influence of Father-to-Child Aggression, Especially for Females

By assessing four common types of family aggression—father-to-child, mother-to-child, father-to-mother and mother-to-child—the present study squarely points to fathers’ aggression directly to their children as setting up a legacy of increased risk of victimization with friends and dating partners. Other studies also show that parents’ aggression directed toward their child, compared to parent-to-parent aggression, relates to victimization from similarly aged peers (e.g., Malik et al., 1997). The analyses examined here were not designed to shed light on why directly experiencing aggression might confer more risk than observing aggression between one’s parents. One possibility, however, is that whereas observing parent-to-parent aggression may set up norms about the acceptability of aggression in close relationships, directly receiving aggression from a parent may result in a more fundamental undermining of one’s own worthiness and self-respect in relationships. In addition, because we assessed all types of family aggression from all three family members (both parents and the adolescent), it also is possible that the adolescents were not fully aware of the extent of their parents’ aggression, whereas they were directly impacted and involved in the parent-to-child aggression.

The second notable finding concerns the impact of fathers’ aggression toward their children as contrasted with mothers’ aggression toward children. Findings to date have been somewhat mixed on the more detrimental impact of father-to-child aggression (Rich et al., 2005) versus mother-to-child aggression (e.g., Hendy et al., 2003; Malik et al., 1997). In the present study, mother-to-child aggression was reported more often than father-to-child aggression, perhaps suggesting that mother-to-child overall aggression may be more normative. Relatedly, prior research suggests that father’s aggression may occur less frequently but may be more threatening and scary to children than mother’s aggression (Margolin & Baucom, 2014), particularly if the aggression is not balanced by more nurturing behaviors. The data here indicate that mothers and fathers showed similar levels of physical aggression but that mothers showed significantly higher levels of psychological aggression. An important future direction would be to directly determine if youth perceive the impact of their parents’ aggression differently.

The findings from the present study clearly point to the influence of fathers’ aggression toward their daughters, particularly as a precursor to their daughters’ victimization by a romantic partner. Whereas gender did not play a moderating role for friend victimization, gender-specific pathways emerged in the risk for dating victimization following exposure to father’s aggression. There is growing attention in both lay (Nielsen, 2008) and scholarly literatures (Allgood, Beckert & Peterson, 2012) that fathers’ behaviors toward their daughters shapes their daughters’ expectations about romantic partners. Although often discussed in terms of positive attributes, such as the respect and support that fathers provide to their daughters, the data here also suggest that negative father-daughter relationship dimensions carry over to dating relationships. Specifically, daughters who have experienced physical and/or psychological aggression from their fathers are more likely to also experience victimization from dating partners. Several other studies on the negative legacy of father-daughter relationships for dating relationships have highlighted the impact of fathers on daughters’ early sexual encounters. For example, less time spent with fathers was associated with earlier age of first sexual intercourse (Byrd-Craven, Geary, Vigil, Hoard, 2007). Moreover, although both mothers’ and fathers’ verbal abuse predicted adolescent girls’ dating violence, only paternal physical abuse predicted adolescent females’ sexual victimization, which in turn related to wide-ranging psychological symptoms (Rich et al., 2005). Although the low endorsement in our study precluded looking specifically at fathers’ influence on their daughters’ sexual victimization, as contrasted with other types of dating victimization, the role of sexual victimization deserves further attention in future studies. Similarly, toward the goal of understanding how father-to-daughter aggression affects daughters’ victimization in dating relationships, other explanatory variables should be explored. For example, do daughters of aggressive fathers date at an earlier age and thereby engage in more risky romantic relationships? Finally, it should be recognized that despite the association between father-to-daughter aggression and daughters’ dating partner victimization, a number of daughters with aggressive fathers do not fit this pattern. Fathers’ aggression may still play a role—but the effect may be to influence their daughters to intentionally select a partner who is quite different from their father. More qualitative data on what daughters look for in a dating partner might fill in some of the gaps about how fathers may influence their daughters’ selection of romantic partners.

Proportion of Friends’ Prosocial-to-Antisocial Behavior as a Protective Factor

Affiliation with prosocial peers has been shown to be protective against risky behaviors, including substance use and perpetration of violence (Prinstein et al., 2001; Spoth, Redmond, Hockaday, & Yoo, 1996). More specific to relationship aggression, girls with friends who hold prosocial beliefs are less likely to perpetrate dating violence (Foshee et al., 2013) and girls who themselves engage in prosocial behaviors, e.g., high grade point averages, strong school attachment, are less likely to be in physically abusive dating relationships (Cleveland, Herrera, & Stuewig, 2003). Adding to this literature, our results show that affiliating with friends who are predominantly prosocial protects adolescent females from dating partner victimization. Our data further indicate that affiliation with predominantly prosocial friends will actually neutralize the risk associated with father-to-daughter aggression. Herrenkohl et al.’s (2008) social developmental model posits that “strong bonds to prosocial others will lessen the risk for negative outcomes, whereas weak bonds to prosocial others will elevate the risk” (p. 94). In line with this model, our data indicate that the important social development process of affiliating with either predominantly prosocial or antisocial friends directly affected the trajectory of continued victimization across generations for females.

To understand the putative impact of affiliation with predominantly prosocial friends, it is best to consider the prosocial-to-antisocial friend construct as both an environment variable, as well as an individual characteristic. Youth reporting a high prosocial-to-antisocial friend ratio surround themselves with friends who are actively involved in school and community activities, who are working hard toward future aspirations, and who are not engaging in high risk or illegal behaviors. Thus, on the one hand, we might conclude that the youth is engulfed in the external positive influences of the friendship network. As previously noted, friends may influence both explicit and implicit norms and attitudes toward dating aggression and may provide models for maintaining intimate relationships without violence or aggression (Capaldi, Dishion, Stoolmiller, & Yoerger, 2001; Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004).

Alternatively, we might view the prosocial-to-antisocial ratio as an individual characteristic that the youth have sought out and cultivated. Also, through a measurement of friends, this ratio may actually reflect the youth’s own prosocial-to-antisocial activities. As in the case of other important protective factors, there often are important mutually reinforcing patterns where youth actively seek out certain relationships and then experience the benefits of those relationships in return (Werner, 1993). Although we assumed there might be some overlap between having predominantly prosocial friends and low friend victimization, we did not find this association. Instead, having predominantly prosocial friends related to low dating partner victimization. Thus, it may be that adolescents who befriend those who engage in predominantly prosocial behaviors also seek out non-aggressive dating partners. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that neither separate construct of prosocial or antisocial friend behavior by itself was significantly associated with victimization; nor was there an inverse relationship between prosocial and antisocial friend behaviors. Rather, it was the proportion of friends’ prosocial-to-antisocial behaviors that emerged as significant, suggesting that adolescent friendships are not easily categorized as prosocial versus antisocial.

Females’ and Males’ Victimization Experiences

The present study is one of the first to examine different types of victimization among a community sample of late adolescents. Although females and males did not report differences in their overall amount of victimization, which is consistent with prior studies for this age group (Archer, 2004), descriptive analyses revealed differences in whether dating partners or friends were the source of certain types of aggression. Specifically, females reported more physical, psychological, and electronic victimization from dating partners than friends, whereas males reported more of these types of victimization from friends than dating partners. In a prior investigation on young adults’ electronic aggression, victimization from dating partners was more distressing than similar victimization from friends (Bennett et al., 2011). Moreover, while females tend to describe victimization as a serious matter, some males describe it more as a joking matter (Kellerman, Margolin, Borofsky, Baucom & Iturralde, 2013; Molidor, Tolman, & Kober, 2000). Thus, greater attention is needed, not only to the amount and predictive factors for dating and friend victimization, but also to understanding the implications of that victimization.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, the study did not include an assessment of aggression perpetration, which tends to correlate highly with victimization (Olsen, Parra, & Bennett, 2010). Incorporating assessments of both victimization and perpetration in the same study would better help understand the implications of these findings. Second, there may be “third variables” that give rise to both family aggression and victimization, such as parents’ poor modeling of emotion regulation or other co-occurring stressors, such as community violence. Third, the nature of dating is quite fluid in this age group and the dating partner victimization reported in this sample over the specific time frame of one year may not reflect the extent of dating victimization experienced by participants. Alternatively, it is possible that some participants who report victimization here later terminate these relationships and avoid such relationships in future. More long-term follow-up about romantic relationship victimization is important to determine whether associations evidenced here would also continue on to later dating relationships. Fourth, information on victimization and friends’ prosocial and antisocial behavior were collected concurrently, making it unclear whether experiences of dating victimization led to affiliation with particular friend groups or vice versa. Fifth, given that the present study initially recruited two-parent families to assess parent-to-parent aggression, the findings might reflect milder forms of inter-parental aggression and may not generalize to youth from one-parent families.

Implications and Conclusions

This study added two new findings to the prior literature related to family aggression and antisocial peers at risk factors for dating partner and friend victimization. First, by disentangling four types of family aggression, the study emphasized the significant deleterious impact of fathers’ aggression. This was highlighted, in particular, through the association of father-to-daughter aggression and daughters’ later dating victimization. Second, the construct of prosocial-to-antisocial friend behavior emerged as a general protective factor against dating partner victimization, as well as a buffer that interrupted the association between father-to-daughter aggression and daughters’ dating victimization. Some reassuring findings that emerged from this study are that youth who witnessed parent-to-parent aggression or experienced mother-to-child aggression did not have a higher risk for dating partner or friend victimization. On the other hand, given the negative and compounding consequences of multiple forms of victimization (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006), the results underscore females’ vulnerability to adverse consequences based on aggression patterns established in the father-daughter relationship. Two potential points of intervention emerge from these data: First, educational and prevention programs aimed directly at fathers could increase their knowledge about the impact of aggression toward their child; second, awareness and efforts to encourage late adolescents, particularly females, to engage with prosocial friends might protect these young women from being victimized in their dating relationships.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by NIH-NICHD Grants R01 HD 046807 and R21 HD 072170 (Margolin, PI), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation Grant 00-12802 (Margolin, PI), and NSF GRFP DGE-0937362 (Han, PI).

We thank our USC Family Studies Project colleagues as well as the families who participated in the study. An abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the 2015 SRCD conference.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allgood SM, Beckert TE, Peterson C. The role of father involvement in the perceived psychological well-being of young adult daughters: A retrospective study. North American Journal of Psychology. 2012;14:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- The American Academy of Pediatrics. [Accessed 31 March 2015];Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. 2008 https://brightfutures.aap.org/pdfs/Guidelines_PDF/18-Adolescence.pdf.

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8(4):291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16(5):427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Foshee VA. Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(2):162–184. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC. Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(7):713–732. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DC, Guran EL, Ramos MC, Margolin G. College students’ electronic victimization in friendships and dating relationships: Anticipated distress and associations with risky behaviors. Violence and Victims. 2011;26(4):410–429. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd-Craven J, Geary DC, Vigil JM, Hoard MI. One mate or two? Life history traits and reproductive variation in low-income women. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2007;39:469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(6):1175–1188. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:61–73. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Straus MA, Brownridge DA, Tiwari A, Leung WC. Prevalence of dating partner violence and suicidal ideation among male and female university students worldwide. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2008;53(6):529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Herrera VM, Stuewig J. Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factor similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, Portera L. Childhood abuse and subsequent sexual assault among female inpatients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9(3):473–482. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung WS, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. 2001;358(9280):450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EC, Buehler C, Fletcher AC. A process model of parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence. Social Development. 2012;21(3):461–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WP, Marte RM, Betts S, Silliman B. Adolescent suicide risk and peer- related violent behaviors and victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(12):1330–1348. doi: 10.1177/088626001016012006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Furman WC. When love is just a four-letter word: Victimization and romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(4):293–298. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST, Faris R, Chang LY, Suchindran CM. The peer context and the development of the perpetration of adolescent dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:471–486. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9915-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido EF, Taussig HN. Do parenting practices and prosocial peers moderate the association between intimate partner violence exposure and teen dating violence? Psychology of Violence. 2013;3(4):354. doi: 10.1037/a0034036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover AR, Kaukinen C, Fox KA. The relationship between violence in the family of origin and dating violence among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güroğlu B, Van Lieshout CF, Haselager GJ, Scholte RH. Similarity and complementarity of behavioral profiles of friendship types and types of friends: Friendships and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(2):357–386. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationships: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Spriggs AL, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization from adolescence to young adulthood in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(5):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy HM, Weiner K, Bakerofskie J, Eggen D, Gustitus C, McLeod KC. Comparison of six models for violent romantic relationships in college men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(6):645–665. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2008;9:84–99. doi: 10.1177/1524838008314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Saudino KJ. Gender differences in psychological, physical, and sexual aggression among college students using the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales. Violence and Victims. 2003;18(2):197–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):948–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Alink LR, Tseng WL, van IJzendoorn MH, Crick NR. Maternal and paternal parenting styles associated with relational aggression in children and adolescents: A conceptual analysis and meta-analytic review. Developmental Review. 2011;31(4):240–278. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman I, Margolin G, Borofsky LA, Baucom BR, Iturralde E. Electronic aggression among emerging adults motivations and contextual factors. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1:293–304. doi: 10.1177/2167696813490159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(3):505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Friendship quality, peer group affiliation, and peer antisocial behavior as moderators of the link between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13(2):161–184. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1302002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Baucom BR. Adolescents’ aggression to parents: Longitudinal links with parents’ physical aggression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS, Foo L. Interactive and unique risk factors for husbands’ emotional and physical abuse of their wives. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13(4):315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Vickerman KA, Oliver PH, Gordis EB. Violence exposure in multiple interpersonal domains: Cumulative and differential effects. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molidor C, Tolman RM, Kober J. Gender and contextual factors in adolescent dating violence. The Prevention Researcher. 2000;7:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L. Between fathers and daughters: Enriching and rebuilding your adult relationship. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M. Factors mediating the link between witnessing interparental violence and dating violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13(1):39–57. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Malone J, Tyree A. Physical aggression in early marriage: Prerelationship and relationship effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(3):594–602. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JP, Parra GR, Bennett SA. Predicting violence in romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A critical review of the mechanisms by which familial and peer influences operate. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Hodges EV, Egan SK. Determinants of chronic victimization by peers. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: Factors that alter or add to peer influence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26(5):287–298. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(4):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Loh C, Weiland P. Child and adolescent abuse and subsequent victimization: A prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(12):1373–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf KK, McCanne TR. Relationship of childhood sexual, physical, and combined sexual and physical abuse to adult victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(11):1119–1133. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. The early socialization of aggressive victims of bullying. Child Development. 1997;68(4):665–675. doi: 10.2307/1132117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(3):349–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Hockaday C, Yoo S. Protective factors and young adolescent tendency to abstain from alcohol use: A model using two waves of intervention study data. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:749–770. doi: 10.1007/BF02511033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk- taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28(1):78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(3):640–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. doi: 10.2307/35733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):297–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(1):13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(3):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina J, Hebert M. Risk factors for victimization in romantic relationships of young women: A review of empirical studies and implications for prevention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8(1):33–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838006297029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. Risk, resilience, and recovery: Perspectives from the Kauai longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:503–516. doi: 10.1017/S095457940000612X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Koss MP. Courtship violence: Incidence in a national sample of higher education students. Violence and Victims. 1991;6:247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(2):277. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]