Abstract

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanics. Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stages of disease and experience poor quality of life following a cancer diagnosis. Cancer outcomes are influenced by a confluence of social, cultural, behavioral and biological factors. Yet, much of the behavioral and psychosocial research in oncology has focused on non-Hispanic Whites, thus limiting our understanding of the potential web of factors that can influence cancer-related outcomes among Hispanics. Furthermore, features of Hispanic ethnicity and culture may influence and interact with, social, psychosocial, health care, disease-specific, and medical factors known to influence cancer-related outcomes, yet very few studies have integrated Hispanic cultural processes when addressing cancer-related outcomes for this ethnic group. Guided by the extant literature in oncology, Hispanic culture and health, and previously established models of determinants of minority health, we present a conceptual model that highlights the interplay of social, cultural, psychosocial, disease-specific, health care, and medical factors as determinants of cancer outcomes (morbidity, mortality, quality of life) and review key evidence of how features of Hispanic culture may influence cancer outcomes and contribute to the disparate outcomes observed in Hispanic cancer samples relative to non-Hispanic Whites. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of future research opportunities and existing challenges to researching oncology outcomes among Hispanics.

Keywords: Review, Cancer, Hispanic, Culture, Psychosocial

Introduction

Among Hispanics and Latinos, hereafter referenced as Hispanics, cancer has surpassed cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death. Approximately 30% of Hispanic men and women in the U.S. will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lifetime (American Cancer Society, 2015b). Despite marked medical improvements in the treatment of cancer and increased survival rates for the general population (American Cancer Society, 2015a), Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stages of disease, have longer times to definitive diagnosis and treatment initiation, and experience poorer quality of life relative to non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs)(American Cancer Society, 2015b). Cancer outcomes specify the health status of individuals and this review focuses on outcomes such as cancer morbidity and mortality rates as well as patient-reported outcomes that reflect subjective health status (e.g., quality of life). Cancer outcomes in the general population are influenced by a host of complementary socioeconomic, cultural, psychosocial, disease-specific, health care, and medical factors (Kagawa-Singer, Valdez Dadia, Yu, & Surbone, 2010; Myers, 2009). However, despite the rapidly increasing Hispanic population in the United States (Macartney, Bishaw, & Fontenot, 2013), the literature predominantly consists of studies targeting NHWs. As these trends indicate, there is an urgent need for more oncology research focusing on Hispanics in the U.S. The purpose of this manuscript is to provide a concise review of determinants of cancer outcomes among Hispanics in the U.S. and posit a conceptual model outlining potential factors that contribute to cancer outcomes among Hispanics. We begin this review with an introduction to our conceptual model on determinants of cancer outcomes and disparities in cancer outcomes among Hispanics in the U.S. Our model focuses on three key outcomes: cancer morbidity, cancer mortality, and quality of life. We proceed with a summary of cancer epidemiology for Hispanics in the U.S. where we highlight several well-established disparities in cancer incidence and mortality. In the subsequent sections we provide support for our conceptual model by summarizing key research findings on determinants of cancer outcomes. Finally, we conclude with a brief discussion on limitations to the literature, existing challenges to research with Hispanics, and provide directions for future research that will add to our understanding of cancer outcomes among Hispanics.

A Conceptual Model of Hispanic Health in Cancer

The paucity of oncology research focusing on Hispanics makes it difficult to fully identify and understand factors that may influence cancer outcomes in this population. Nonetheless, there are well-established models such as the Reserve Capacity Model, and the Lifespan Biopsychosocial Model of Cumulative Vulnerability and Minority Health (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Myers, 2009), which suggest that being a member of an ethnic minority may confer risk for poor health outcomes as a result of fewer socioeconomic resources and additional sources of stress exposure caused in part by social disadvantage. Additionally, Meyerowitz’s meditational framework linking ethnicity to cancer outcomes posits that cultural factors predict cancer outcomes through access to care, cancer-related cognitions, and adherence behaviors (Meyerowitz, Richardson, Hudson, & Leedham, 1998). All of these models provide a strong, conceptual framework to better understand how multiple factors may affect chronic disease risk and outcomes among ethnic/racial minorities and can be used to inform the development of a culturally specific model for Hispanic cancer outcomes.

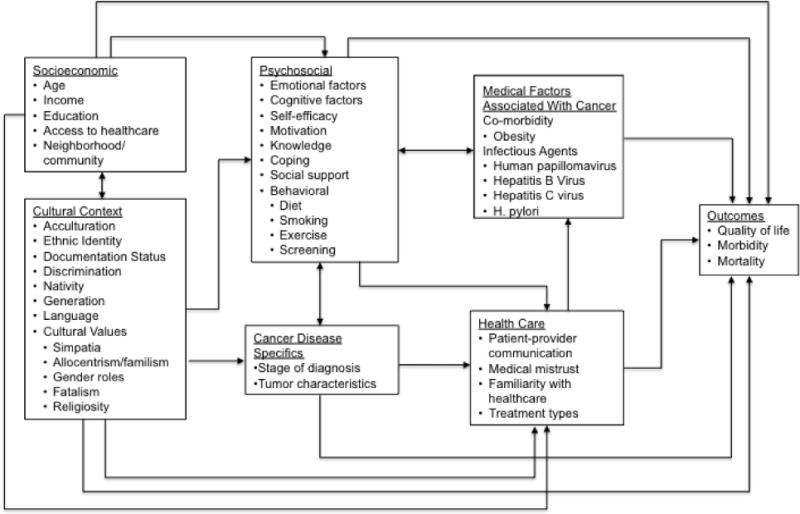

In our development of a conceptual model on determinants of cancer-related outcomes, we drew from the existing literature that describes aspects of Hispanic culture to elucidate how culture can both place Hispanics at risk for deleterious cancer outcomes and facilitate resiliency within the cancer context. We integrated this information into our conceptual framework by highlighting the influence of cultural factors on outcomes such as morbidity, mortality, and quality of life. Our model begins with socioeconomic and cultural factors as initial determinants of cancer outcomes and transitions to intermediate, potentially modifiable targets such as psychosocial factors, health care factors, cancer disease-specific factors, and medical factors. Unlike established models of ethnicity and health outcomes (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Myers, 2009), our model is both tailored to Hispanics and cancer-specific (see Figure 1). Therefore, it incorporates key Hispanic cultural factors as determinants of cancer outcomes and includes medical (e.g., diseases associated with cancer risk) and health care factors (e.g., access) that are relevant to Hispanics in the U.S. as well as cancer disease-specific factors (e.g., stage of diagnosis, tumor characteristics). An inherent limitation of past models is the lack of attention to the potential pathways through which Hispanic cultural components such as language, values and beliefs can positively and negatively affect cancer outcomes. Therefore, our model posits that cultural factors are key to understanding cancer outcomes in the U.S.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of determinants of cancer outcomes in Hispanics. Socioeconomic and cultural factors are interrelated and indirectly contribute to cancer outcomes through a series of modifiable factors such as psychosocial factors (e.g., coping, support, behaviors), cancer disease-specific factors (e.g., tumor characteristics), health care factors (e.g., cancer treatments, patient-physician communication), and medical factors associated with cancer (e.g., infectious agents and obesity).

Cancer Outcomes among Hispanics in the U.S

Similar to the U.S. general population, prostate cancer and colorectal cancers are the most commonly diagnosed cancers among Hispanic men and breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among Hispanic women. Although lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in the general U.S. population, thyroid cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed among Hispanic women followed by colorectal cancers (American Cancer Society, 2015b). It is important to note that two of the most commonly diagnosed cancers among Hispanics, breast and colorectal cancers, have existing screening guidelines in place that can help detect the disease before spreading to other organs of the body. Compared to NHWs, cancer incidence rates are generally lower among Hispanics, especially for lung cancer for which the incidence rate among Hispanics is about 50% less than in NHWs (American Cancer Society, 2015b). There are only a handful of cancers for which Hispanics in the U.S. have higher incidences relative to NHWs: gallbladder, acute lymphocytic leukemia, and cancers associated with infectious agents (e.g., gastric, liver) that are often seen in economically developing countries in Central and South America and persist among Hispanics who have migrated from these countries to the U.S. (American Cancer Society, 2015b).

Regarding cancer mortality outcomes, findings from epidemiological studies indicate that while cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death among non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs) and African Americans, cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanics and accounted for approximately 22% of all Hispanic adult deaths in the U.S. in 2012 (American Cancer Society, 2015b). Lung cancer is the leading cancer-related cause of death among Hispanic males and breast cancer is the leading cancer-related cause of death among Hispanic females. In general, Hispanic cancer death rates are lower among Hispanics than NHWs. There are a few cancers for which Hispanics have higher death rates relative to NHWs. For example, Hispanics diagnosed with liver and stomach cancer have higher cancer death rates than their NHW counterparts (American Cancer Society, 2015b). The five-year cause-specific survival rate for Hispanic men is 66% and the five-year cause-specific survival rate for Hispanic women is 70%. These rates are similar to the 68% five-year cause-specific survival rates reported for NHW men and women (American Cancer Society, 2015b).

Regarding quality of life outcomes, Hispanics diagnosed with cancer report poorer quality of life compared to NHWs and other minority groups. A meta-analysis on psychological morbidity among ethnic minority groups, many of whom were diagnosed with breast cancer, found that Hispanics experienced significantly greater distress, worse social well-being, and worse overall quality of life compared to other ethnic minority groups such as Asian and Pacific-Islanders, even after adjusting for socioeconomic differences (Luckett et al., 2011). However, studies comparing quality of life among Hispanics to NHWs are predominantly cross-sectional and have mostly focused on women diagnosed with breast cancer. In breast cancer, studies generally show that Hispanics are more likely to report poorer quality of life (emotional functioning, physical functioning, social functioning) relative to NHWs (for a review of the literature see Yanez, Thompson, & Stanton, 2011). Of these multiple quality of life domains, the greatest disparity is observed in the emotional functioning domain where Hispanics report poorer quality of life compared to NHWs and African American breast cancer survivors (Yanez, Thompson, & Stanton, 2011).

Although fewer studies have examined quality of life outcomes among Hispanics with prostate cancer, a handful of studies suggest that men diagnosed with prostate cancer evidence lower quality of life compared to NHWs. (Krupski et al., 2005; Penedo, Dahn, Shen, Schneiderman, & Antoni, 2006). More specifically, Hispanic men diagnosed with prostate cancer have reported poorer quality of life relative to NHWs and African Americans. The disparity in overall quality of life between NHWs and African Americans was explained by income but the disparity in quality of life between NHWs and Hispanic was only partially explained by income, suggesting that additional medical factors may account for poorer quality of life in Hispanics relative to NHWs (Penedo et al., 2006). Regarding prostate cancer specific symptoms, Hispanic men diagnosed with prostate cancer report worse bowel functioning than African Americans and NHWs, even after adjusting for sociodemographic and medical covariates (Krupski et al., 2005). As in the breast cancer literature, many of the observational studies on Hispanic men with prostate cancer are cross-sectional and more longitudinal studies are needed to better compare determinants of quality of life outcomes over time and identify possible intermediate processes (e.g., delays in diagnosis and treatment, social support, language barriers, patient-physician communication) in the relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and cancer outcomes.

Determinants of Cancer Outcomes among Hispanics in the U.S

Socioeconomic Factors

Attempts to explain disparities in cancer outcomes have largely focused on examining the role of socioeconomic factors and their influence on limiting access to care (Ward et al., 2004). The focus on socioeconomic factors is warranted given that, on average, Hispanics are more likely to struggle with economic adversity and are overrepresented in lower socioeconomic strata compared NHWs (Macartney et al., 2013). Hispanics are also twice as likely to be living below the federal poverty level compared to NHWs (Macartney et al., 2013) and compared to NHWs and African Americans, Hispanics are less likely to have health insurance (Doty, Blumenthal, & Collins, 2014). In light of these documented disparities, socioeconomic status has emerged as a pivotal determinant of health outcomes, especially for ethnic minorities such as Hispanics.

There are numerous ways in which low socioeconomic status can disproportionately and negatively affect outcomes among Hispanics. Specific to Hispanics, poverty, limited access to care, lack of health insurance, limited work flexibility or medical leave, and lower educational status can severely limit access to preventive care and cancer screening, increase daily stress, reduce cancer treatment options and adherence to treatments, all of which can negatively affect cancer morbidity, mortality, and quality of life outcomes (American Cancer Society, 2015b; Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa, Padilla, Bohorquez, Tejero, & Garcia, 2006; Freeman, 2004; Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010). For example, Hispanics have more financial needs after completion of primary treatment for cancer compared to African Americans and NHWs (Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006; Moadel, Morgan, & Dutcher, 2007). Lack of health insurance and limited financial resources to pay for treatments indirectly affects cancer outcomes by limiting both standard treatment approaches to cancer and access to cancer clinical trials that can provide life extending or life saving treatments. In light of the pivotal role of socioeconomic status in relation to cancer outcomes, our conceptual model (see Figure 1) includes socioeconomic factors as important, initial determinants cancer outcomes.

Hispanic Cultural Factors

Culture is often regarded as a core system of shared beliefs, values and lifestyles among a particular group (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010). Hispanic culture may shape various aspects of the cancer experience, from engagement in preventive health behaviors to treatment decision-making, illness perceptions, and coping with a cancer diagnosis and concomitant side effects. Cultural factors relevant to Hispanics include Spanish language use, Hispanic ethnic identity (e.g., attachment and belonging to ethnic group) (Phinney & Ong, 2007), nativity, generational status, and values and beliefs salient to Hispanics (Gallo et al., 2009). Marin and Marin (1991) have described several values and beliefs relevant to Hispanic culture. Allocentrisim and familism, for example, are cultural views in which the needs and objectives of the family are placed over the needs of the individual, and strong attachments to the nuclear and extended family are emphasized. Simpatía reflects a preference towards pleasant and non-confrontational social interactions that often results in avoiding interpersonal conflict and consequently may foster socially desirable responses. Gender roles within the Hispanic culture often follow a pattern of male dominance (machismo) and female submissiveness (marianismo). Religiosity/Spirituality is another important aspect of Hispanic culture, with Hispanics often considering religion as a source of support during health adversities (Gallo, Penedo, Espinosa de los Monteros, & Arguelles, 2009; Marin & Marin, 1991). Fatalism, which is the belief that problems are out of one’s hands and determined by fate, is also another value often endorsed by Hispanics (Facione, Miaskowski, Dodd, & Paul, 2002; Barbara D. Powe, 1995).

Culturally specific values and beliefs are not static but evolve over time through the process of acculturation. Acculturation is the multidimensional process of cultural change resulting from the meeting of groups or individuals of different cultures and has implications for health (Gibson, 2001). The process of acculturation among Hispanics in the U.S. is a critical factor in the relationship between culture and cancer outcomes. Given that low acculturation among Hispanics is generally associated with lower SES and less access to health care, the finding that foreign-born Hispanics and less acculturated Hispanics tend to have lower all-cause mortality is a counterintuitive phenomenon often referred to as the “Hispanic paradox.” Emerging data suggest that the paradox might also exist for cancer outcomes. For example, compared to lower acculturated Hispanics, more acculturated Hispanics have higher cancer rates that are similar to NHWs (Pinheiro et al., 2009), and overall cancer mortality rates are higher among U.S. born Hispanics than foreign-born Hispanics (Patel, Schupp, Gomez, Chang, & Wakelee, 2013; Singh & Hiatt, 2006). Hispanic acculturation has been linked to increased use of English language as well as greater familiarity with the U.S. health care system and greater access to health care (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010). However, in the general Hispanic population, greater acculturation has also been associated with increased stress, family conflicts, psychological disorders, adoption of unhealthy behaviors (e.g., poor diet), and loss of familial support (Gallo et al., 2009; Lopez-Class, Castro, & Ramirez, 2011).

Moving beyond the mere assessment of acculturation to assessing values, beliefs, practices relevant to Hispanic culture (e.g., familism, religiosity, simpatía, language use, ethnic identity) provides a richer understanding of how Hispanic culture can contribute to cancer outcomes. Language use, for example, has been identified as a more important predictor of quality of life among Hispanic breast cancer survivors than nativity status (Graves et al., 2012). One interpretation of this findings is that English language use or congruent language use with providers facilitates better quality of life through better patient-provider communication and treatment satisfaction (Yanez, Stanton, & Maly, 2012). Much of our understanding of how cultural factors are relevant to cancer experiences come from studies on Hispanic breast cancer survivors in which women have revealed concerns about family members having negative attitudes, stigma about cancer, and fatalism, which is associated with poorer quality of life among breast cancer survivors (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006; Graves et al., 2012). Other Hispanic values and beliefs tend to have more complicated associations with cancer outcomes. For example, another Hispanic cultural value, familism can facilitate support from family members for patients undergoing diagnosis and treatment (Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006; Kimlin Tam Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004) and has been associated with more favorable quality of life among breast cancer survivors (Graves et al., 2012). However, familism can also hinder favorable cancer outcomes under certain contexts. For example, Hispanic patients with the majority of their family residing outside of the U.S. may struggle to receive much desired familial support when confronting illness, potentially fueling or exacerbating feelings of isolation. Additionally, instances of family conflict might mitigate familial support during stressful life events, increasing feelings of distress over time. Familism and female gender roles such as marianismo may also inhibit an individual’s willingness to adopt positive behavioral and health changes that are not perceived as benefiting the family. Indeed, Hispanic women treated for breast cancer have expressed concerns about not wanting to burden their family with their diagnosis and coped by focusing on their familial responsibilities over themselves (Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006). Machismo has also been a concern identified by Hispanic women diagnosed with cancer, with some women reporting abandonment by their husbands as a result of their diagnosis (Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006; Lopez-Class, Perret-Gentil, et al., 2011). However, it is also possible that men who manifest machismo through strong family provider instincts or protective feelings might be more inclined to provide support to family members diagnosed with cancer. Taken together, these examples and findings from the literature demonstrate how Hispanic values and beliefs are expressed in several ways and therefore can have varying effects on cancer outcomes.

The emerging data, albeit limited, suggests that cultural factors are neither fully protective nor deleterious and more studies are needed to explore the complex ways in which culture is related to cancer outcomes. More specifically, additional studies are needed to disentangle acculturation, ethnic identity, and nativity and their relationship to cancer outcomes. Other relevant but unexplored aspects relevant to Hispanic culture such as documentation status and perceived discrimination also require greater attention in the cancer literature. Finally, less research has focused on machismo and simpatía and additional research is needed to elucidate the pathways through which these cultural values and beliefs predict cancer outcomes. For example, although Hispanic women with breast cancer have mentioned that their view of gender roles have been important cultural beliefs that have shaped their experience with cancer, our understanding of how gender roles such as machismo shape men’s experiences with cancer is not well explored. Although a growing number of studies are establishing a relationship between Hispanic cultural factors and cancer outcomes, our understanding of how cultural factors relate to psychosocial, medical, and health care system factors to predict cancer outcomes remains limited.

Psychosocial Factors

Few studies have evaluated the influence of psychosocial factors such as coping and social support on cancer outcomes among Hispanics. Within the few studies that have focused on Hispanics, familism has been identified as an important cultural process that facilitates a strong social support network in the context of coping with cancer (Kimlin T. Ashing-Giwa et al., 2006). It also appears that lower acculturation may be associated with greater life satisfaction. In a study of mostly long-term survivors of breast and prostate cancer, lower acculturated Hispanic cancer survivors reported higher life satisfaction than higher acculturated Hispanics, and this relationship was partially explained by the higher levels of social support found among lower acculturated survivors (Stephens, Stein, & Landrine, 2010). Regarding coping strategies, compared to NHWs, both African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to endorse coping through religion or spiritual beliefs in the cancer context (Culver, Arena, Antoni, & Carver, 2002; Culver, Arena, Wimberly, Antoni, & Carver, 2004; Moadel et al., 2007). In some studies, coping through religion or spiritual beliefs among Hispanics has been associated with lower levels of distress and better overall quality of life (Culver et al., 2004; Thuné-Boyle, Stygall, Keshtgar, & Newman, 2006; Wildes, Miller, de Majors, & Ramirez, 2009). Taken together, these findings begin to illustrate potential pathways from Hispanic cultural factors on psychosocial factors such as coping strategies and ultimately cancer outcomes.

Behavioral Factors

Smoking

One of the most common risk factors for developing cancer is smoking. Overall, Hispanics report significantly less tobacco use compared to NHWs. Less tobacco use is a likely explanation for why Hispanics have lower lung cancer morbidity and mortality relative to NHWs (American Cancer Society, 2015b). However, Hispanics also report lower rates of attempts to quit smoking, especially for intermittent smokers when compared to NHWs (29% v. 43% respectively) (Kahende, Malarcher, Teplinskaya, & Asman, 2011; Trinidad, Pérez-Stable, White, Emery, & Messer, 2011). In addition, acculturation tends to increase smoking rates as Hispanics spend more time in the US (Abraído-Lanza, Chao, & Flórez, 2005; Smith, Ramsay, & Mazure, 2014; Wong et al., 2013), a finding that supports the notion that greater acculturation may place Hispanics at greater risk for developing cancer.

Screening

Engagement in cancer screening is an important prevention method that facilitates early detection of cancers at potentially more treatable stages of the disease. As depicted in our conceptual model, cultural factors can also influence the likelihood of cancer screening, and data indicate that Hispanics are generally less likely to adhere to cancer screening recommendations than NHWs (DuBard & Gizlice, 2008; Howe et al., 2006; Shi, Lebrun, Zhu, & Tsai, 2011; Wells & Roetzheim, 2007; Zonderman, Ejiogu, Norbeck, & Evans, 2014). For example, Hispanics underuse colorectal cancer screening compared to NHWs (American Cancer Society, 2015b; Shah, Zhu, & Potter, 2006), and Hispanics are less likely to engage in mammography screening than NHWs. Cancer screening underuse is partially a function of the socioeconomic difficulties faced by Hispanics in regards to accessing care (e.g., cost, insurance status, usual source of care) (Gonzalez et al., 2012). Moreover, underuse of cancer screening methods and delayed follow-up after abnormal screening are potential reasons for why Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed at more advanced stages of breast and colorectal cancers (American Cancer Society, 2015b). Foreign-born Hispanic women, in particular, have lower rates of screening for breast and cervical cancers, but not when controlling for socioeconomic factors (Rodríguez, Ward, & Pérez-Stable, 2005; Schootman, Jeffe, Baker, & Walker, 2006). Hence, overcoming the practical barriers associated with lower socioeconomic status to improve screening rates for women’s cancer is an important goal. Regarding colorectal cancers, Hispanics, especially Spanish-speaking Hispanics, have significantly lower rates of screening for colorectal cancer compared to NHWs. Although having established health care and insurance coverage have been identified as significant predictors of cancer screening in Hispanics, (Gonzalez et al., 2012; Rodríguez et al., 2005; Sheinfeld Gorin & Heck, 2005; Wells & Roetzheim, 2007), disparities in screening rates between Hispanics and NHWs do not always diminish when adjusting for socioeconomic and health insurance factors (Liss & Baker, 2014). Cultural factors such as language barriers, health literacy and values and beliefs about screening and cancer may play a role in Hispanic screening rates. Fatalism, for example, is related to poorer cancer screening adherence among Hispanics (Lopez-McKee, McNeill, Bader, & Morales, 2008; Barbara D Powe & Finnie, 2003), even when structural barriers (e.g., socioeconomic status) have been factored out (Espinosa de los Monteros & Gallo, 2011; Sheinfeld Gorin & Heck, 2005). Hispanics have also reported that embarrassment, machismo, and fatalism are barriers towards colorectal and prostate cancer screening (Getrich et al., 2012; Rivera-Ramos & Buki, 2011). Lack of knowledge and awareness of cancer and screening methods have also been identified by Hispanics as additional psychosocial barriers to screening for cancer (Cameron, Francis, Wolf, Baker, & Makoul, 2007; Walsh et al., 2004). Despite these noted barriers, recent data suggest that screening rates, especially for Hispanics, might be on the rise (Gonzalez et al., 2012).

Cancer Disease-Specific Factors

Disparities in clinical and patient-reported cancer outcomes are driven by numerous factors, including disease-specific factors such as stage of diagnosis and tumor characteristics. For example, patients diagnosed with advanced stages of disease, as opposed to earlier stages of disease, generally have poorer cancer prognoses. Additionally, the type of tumor characteristics often has implications for the availability and types of cancer treatment. These disease characteristics influence course of treatment, symptom burden, cancer progression, and mortality rates. Furthermore, certain disease characteristics also disproportionally affect lower income and racial/ethnic minority patients. Compared to NHWs, Hispanics are more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages of breast and colorectal cancer, two cancers for which screening methods exist (American Cancer Society, 2015b). This disparity may be driven in part by limited access to care and cancer screening opportunities among lower income minorities as well as culturally held beliefs about cancer screening (Espinosa de los Monteros & Gallo, 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2012). Another finding in the literature indicates that compared to NHWs, Hispanic and African American women are more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer, a type of breast cancer that is associated with fewer treatment options such as hormonal therapy for breast cancer (Lara-Medina et al., 2011).

Health Care Factors

Health care factors such as patient-physician communication, knowledge and cancer treatment factors play pivotal roles in determining cancer outcomes and disparities. Hispanics and African Americans report more unmet cancer treatment information needs (e.g., information on side effects and pain management) and psychosocial needs (e.g., coping, stress management) compared to NHWs, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors (Moadel et al., 2007). Furthermore, Hispanic and African American women are more likely to have chemotherapy treatment delays compared to NHWs and are also more likely to underuse adjuvant treatment compared to NHWs (Bickell et al., 2006; Fedewa, Ward, Stewart, & Edge, 2010). African Americans and Hispanics are less likely than NHWs to be aware of available cancer clinical trials during their treatment and have lower enrollment rates in clinical trials (Wallington et al., 2012), a disparity that is partially driven by socioeconomic status and access to health insurance. Consequently, Hispanic and African American patients are disadvantaged with regards to receiving potentially life-saving treatments.

Cultural factors play an important role in shaping Hispanics’ interactions with the U.S. health care system and their interactions with health care providers. For example, simpatía (i.e., non-confrontational interactions) can reduce conflict and facilitate pleasant interactions among Hispanics and their health care providers. However, simpatía may also prevent Hispanics from proactively engaging with their health care providers and limit the effectiveness of patient-provider communication (Barrera Jr, Castro, Strycker, & Toobert, 2013; Gallo et al., 2009). Cultural misunderstandings and language barriers between health care providers and Hispanic patients may not only hinder important communication about cancer diagnosis and treatment but also hinder important decision making about cancer treatments (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010). Among Hispanic breast cancer survivors, poor patient-physician communication has been associated with patient dissatisfaction as well as lower quality of life (Maly, Stein, Umezawa, Leake, & Anglin, 2008; Yanez et al., 2012). Not surprisingly, low-acculturated Hispanics, who are more likely to speak Spanish, report greater difficulty understanding cancer-related written materials compared to NHWs (Janz et al., 2008), and Hispanics with higher levels of acculturation might face fewer language barriers when communicating with health care providers and may benefit from greater familiarity with the U.S. health care system. Additionally, Hispanics’ experiences of biased care, or discrimination within the U.S. healthcare system, may also engender medical mistrust towards health care providers and institutions (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010; Varela, Jandorf, & DuHamel, 2010).

Medical Factors

Hispanics have higher rates of cancers that are associated with infectious agents often found in economically developing countries (American Cancer Society, 2015b). These infectious agents place Hispanics at risk for developing certain cancers even after migration to the U.S. and likely contribute to some of the documented disparities in cancer rates between Hispanics and NHWs living in the U.S. Liver cancer, for example, is more prevalent in Hispanics, especially foreign-born Hispanics who are at an increased risk of contracting Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C (American Cancer Society, 2015b; Cokkinides, Bandi, Siegel, & Jemal, 2012). The H. pylori bacterial infection is a risk factor for developing gastric cancer and is more commonly found in foreign-born Hispanic populations than Hispanics born in the U.S. and Hispanics living in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods that may have poorer sanitary conditions (Chang et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings on infectious agents reveal that Hispanic cultural factors such as nativity can increase cancer risk. As another example, although vaccinations are available to reduce many of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections that increase cervical cancer risk, cervical cancer rates are also higher in Hispanics living in the U.S. compared to NHWs. Among Hispanic adolescents, rates of initiating this HPV vaccine are comparable to NHW adolescents. However, relative to NHWs, fewer Hispanics complete the 3 doses of the series, leaving them at risk for developing cervical cancer (Cokkinides et al., 2012). Future research should continue to evaluate psychosocial, socioeconomic, and cultural factors (e.g., gender roles, disease stigma, language barriers) that may contribute to poorer adherence with follow-up vaccines among Hispanics.

In the general U.S. population, diseases such as obesity have also been associated with cancer morbidity and mortality. The majority of research on obesity as a risk factor for cancer has focused on breast cancer, although obesity is related to cancer mortality in prostate, endometrial, and colorectal cancers as well, and few studies have focused on how ethnicity impacts risk (Schmitz, Agurs-Collins, Neuhouser, Pollack, & Gehlert, 2014). Hispanic women of Mexican descent are more likely to be obese than Hispanic men and NHWs and longer duration in the U.S. is associated with greater weight gain (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). The higher cost of healthy food relative to fast food and geographic location of Hispanic ethnic enclaves, which are more likely to be situated in food deserts with fewer recreational resources that facilitate exercise, are important social contributors to the increasing rates of obesity among Hispanics in the U.S. (Kirby, Liang, Chen, & Wang, 2012). The effect of obesity specifically on breast cancer risk in US Hispanics is complex (Sarkissyan, Wu, & Vadgama, 2011; Slattery et al., 2007). Greater body mass index (BMI) is related to increased breast cancer risk for NHW (American Cancer Society, 2015b). Although not consistent across all studies, some data indicate that obesity is predictive of breast cancer-specific morality among Hispanic women (Kwan et al., 2014; Slattery et al., 2007; White, Park, Kolonel, Henderson, & Wilkens, 2012). In addition, studies which have evaluated the impact of weight gain from adolescence to usual adult weight have found inconsistent evidence for relationships to breast cancer risk in Hispanic women with at least one study finding increased risk for those who gained weight (Wenten, Gilliland, Baumgartner, & Samet, 2002) and another finding reduced risk for those who gained weight (Slattery et al., 2007). Future research should evaluate other facets of the socioeconomic and cultural context (i.e., nativity, SES, acculturation) and behaviors (i.e., diet, physical activity) that influence obesity in Hispanic populations to determine whether obesity or its associated factors such as endogenous hormones increase cancer risk in Hispanics. Furthermore, given the potential for diseases such as obesity to predict cancer outcomes among Hispanics, interventions targeting weight loss among Hispanic women could be critically important to preventing cancer-related deaths among this patient population.

As depicted in our conceptual model, medical factors not only predict cancer outcomes but may also have a reciprocal effect on psychosocial factors. Therefore, receiving a medical diagnosis may prompt individuals to engage in more health promoting behaviors such as preventive screening and exercise, and can lead to increases in social support and increased knowledge and motivation. For that reason, the onset of certain medical diagnoses can be viewed as a teachable moment and pivotal intervention period among Hispanics.

Interventions to Improve Cancer Outcomes in US Hispanics

Cancer Early Detection

Interventions designed to increase cancer screening have predominantly focused on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers, with results of varying levels of success. A review of intervention studies that sought to increase breast cancer screening in Hispanics found that approximately half of the interventions included in the review had a positive effect on screening behaviors (Molina, Thompson, Espinoza, & Ceballos, 2013). A recent review of cervical cancer screening interventions specifically targeting Hispanics revealed that roughly a third of interventions were effective at increasing screening (Mann, Foley, Tanner, Sun, & Rhodes, 2015). Given the diversity of samples and delivery sites evaluated, ranging from entire communities to small, targeted groups such as clinic patients, churches, or farm workers, identifying the most effective aspects of these diverse interventions has been challenging. Successful components such as use of lay health advisors (LHAs) and community-based participatory approaches were not consistently associated with improvement in screening for Hispanics diagnosed with varying cancers (Mann et al., 2015; Rhodes, Foley, Zometa, & Bloom, 2007). The heterogeneity of LHA interventions may be occluding the effective features of these programs, because LHAs may serve a variety of functions beyond simply providing brief educational materials. Other promising intervention features include combining education from LHAs with scheduling assistance, follow-up contact, or provision of free or reduced cost screenings, although additional studies with longer follow-up intervals are needed to evaluate these components fully (Mann et al., 2015). The results of colorectal cancer screening promotion programs are more promising (Moralez, Rao, Livaudais, & Thompson, 2012), likely due in part to the provision of free tests and the focus on providing interventions to those already attending healthcare clinics.

Cancer Control and Survivorship

Compared to interventions that focus on cancer prevention and control among Hispanics, fewer interventions have targeted Hispanics diagnosed with cancer and those who have completed cancer treatment and transitioned to survivorship (Molina et al., 2013). Patient navigation studies among Hispanic women diagnosed with breast cancer have had some success in facilitating receipt of timely cancer treatment (Dudley et al., 2012; Ramirez et al., 2014). Theoretically driven, evidence-based psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapies that focus on stress management, relaxation skills, coping skills, communication skills and social support have been associated with improved emotional well-being, reduced depressive symptoms, and reduced symptom burden among Hispanic patients diagnosed with breast or prostate cancer (Ashing & Rosales, 2014; Hughes, Leung, & Naus, 2008; Napoles et al., 2015; Penedo et al., 2007). These studies have demonstrated varying degrees of success in improving quality of life outcomes, with one of the most consistent areas of improvement being in emotional well-being.

Despite their promise, there are many gaps in the literature on interventions for Hispanics diagnosed with cancer. To begin with, the majority of interventions have focused on early detection of cancer and more studies focusing on cancer control and survivorship are needed. Additionally, many of the studies on quality of life outcomes have focused on women with breast cancer and more studies are needed to focus on the quality of life and symptom burden reported by Hispanics diagnosed with other cancers such as lung cancer and gastrointestinal cancers. Another significant gap in the literature is the lack of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions for patients with cancer. Culturally adapted evidence-based interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapies enhance recruitment and retention of minorities and are effective at improving outcomes across conditions such as depression, HIV/AIDS, asthma, and diabetes (Barrera Jr et al., 2013). The goal of culturally adapted studies is not to promote change in culturally held beliefs and values such as familism and marianismo but rather to systematically ensure that each aspect of the intervention is relevant to Hispanics. Cultural adaptation includes training of intervention staff to be culturally sensitive, conducting linguistic adaptation of the intervention material into Spanish, incorporating evidential strategies relevant to Hispanics, and focusing on Hispanic values and behaviors such as familism when delivering intervention targets (e.g., stress management, coping skills training) (Barrera et al., 2014). However, the utility of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions for Hispanics with cancer has not been explored. Therefore, it remains to be seen whether Hispanics would receive any added benefit from culturally adapted interventions, or whether standard, evidence-based interventions are equally effective across ethnic groups.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The current manuscript provides a review of literature on cancer outcomes among Hispanics and provides a conceptual model for understanding determinants of cancer outcomes among Hispanics. Our model draws from established conceptual models on minority health and several key studies on determinants of cancer outcomes among Hispanics. The literature has documented several important disparities in cancer outcomes. However, aside from the contribution of socioeconomic factors, the underlying causes of these disparities are not well elucidated. Our review highlights several examples of socioeconomic and how cultural factors shape the cancer experience for Hispanics and confers both risk and resiliency in relation to cancer outcomes via indirect pathways and interactions with psychosocial factors, cancer disease characteristics, health care system factors, and medical factors. Although many of the direct pathways in our model are supported by the literature (e.g., socioeconomic status predicting psychosocial and behavioral factors, medical factors predicting cancer outcomes), additional research is needed to verify all the indirect pathways through which socioeconomic status and culture predict cancer outcomes. Many of the observational studies focusing on factors related to cancer outcomes among Hispanics are cross-sectional and have not fully explored the effects of psychosocial, cancer disease-specific, medical, and health care factors in the relationship between socioeconomic status, ethnic status and cancer outcomes. Therefore, more longitudinal studies are needed to address whether health behaviors such as colorectal screening mediate the relationship between Hispanic gender roles such as machismo and colorectal cancer morbidity, or what specific psychosocial and behavioral constructs interact with familism to predict better quality of life outcomes over time for Hispanic survivors. As more studies continue to investigate cancer-related outcomes among Hispanics, the literature would benefit from a systematic review of disparities in cancer outcomes between Hispanics and NHWs as well as other racial/ethnic groups.

A major limitation of the literature on Hispanics and cancer is the lack of attention to Hispanic heterogeneity. To begin with, differences in cancer outcomes by Hispanic subgroups have not been well documented and the overwhelming majority of observational and intervention studies have not systematically attended to subgroups of Hispanic ancestry. Cultural variations across Hispanic subgroups likely influence the cancer experience and cancer outcomes in varying ways. The heterogeneity within the Hispanic population presents both challenges and opportunities for future research. Conducting large-scale, longitudinal studies that include multiple Hispanic subgroups is costly and requires time. Furthermore, studies seeking to include a representative sample of Hispanics will require additional time to translate and validate the study-related materials into Spanish by culturally informed research staff.

Another major limitation in the area of Hispanics and cancer is the lack of understanding of cancer-specific biological factors among Hispanics. The overwhelming majority of research on biological differences in cancer types has focused on African American women, as they are more likely to be diagnosed with aggressive tumors compared to NHWs. However, relative to studies focusing on African American women, fewer studies have documented biological differences among Hispanic women’s breast cancer relative to other racial/ethnic groups. The etiological basis of racial and ethnic differences in triple negative breast cancer remains unknown, and more research is needed to investigate biological differences and genetic mutations in cancer types, especially among Hispanics.

In conclusion, racial/ethnic disparities in cancer outcomes are well documented and continue to persist. Hispanics are the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority population in the U.S. and identification of the complex set of contributors to cancer outcomes and disparities is an important public health goal. Key findings from the literature were used to guide the development of our conceptual model focusing on socioeconomic, cultural, psychosocial, health care, cancer disease characteristics, and medical determinants of cancer outcomes and underlying determinants of cancer disparities. The current manuscript also focuses on several modifiable factors that have been the targets of a small but growing number of interventions designed to improve cancer outcomes among Hispanics. Considering the growing number of Hispanics that have gained access to the U.S. health care system as a result of the Affordable Care Act, improving management strategies for Hispanics with chronic diseases is an especially important area of continued inquiry (Doty et al., 2014).

References

- Abraído-Lanza Ana F, Chao Maria T, Flórez Karen R. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(6):1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. 2015a from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036845.pdf.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2015–2017. 2015b Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-034778.pdf.

- Ashing Kimlin, Rosales Monica. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23(5):507–515. doi: 10.1002/pon.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa Kimlin T, Padilla Geraldine V, Bohorquez Dianne E, Tejero Judith S, Garcia Manuela. Understanding the Breast Cancer Experience of Latina Women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2006;24(3):19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa Kimlin Tam, Padilla Geraldine, Tejero Judith, Kraemer Janet, Wright Karen, Coscarelli Anne, Hills Dawn. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(6):408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Manuel, Jr, Castro Felipe G, Strycker Lisa A, Toobert Deborah J. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(2):196–205. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickell Nina A, Wang Jason J, Oluwole Soji, Schrag Deborah, Godfrey Henry, Hiotis Karen, Guth Amber A. Missed Opportunities: Racial Disparities in Adjuvant Breast Cancer Treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(9):1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron KA, Francis L, Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Investigating Hispanic/Latino perceptions about colorectal cancer screening: a community-based approach to effective message design. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Ellen T, Gomez Scarlett Lin, Fish Kari, Schupp Clayton W, Parsonnet Julie, DeRouen Mindy C, Glaser Sally L. Gastric Cancer Incidence among Hispanics in California: Patterns by Time, Nativity, and Neighborhood Characteristics. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21(5):709–719. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-11-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides Vilma E, Bandi Priti, Siegel Rebecca L, Jemal Ahmedin. Cancer-related risk factors and preventive measures in US Hispanics/Latinos. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62(6):353–363. doi: 10.3322/caac.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver Jenifer L, Arena Patricia L, Antoni Michael H, Carver Charles S. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing african americans, hispanics and non-hispanic whites. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11(6):495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver Jenifer L, Arena Patricia L, Wimberly Sarah R, Antoni Michael H, Carver Charles S. Coping among african-american, hispanic, and non-hispanic white women recently treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychology & Health. 2004;19(2):157–166. doi: 10.1080/08870440310001652669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doty MM, Blumenthal D, Collins SR. The affordable care act and health insurance for latinos. Jama. 2014;312(17):1735–1736. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBard C Annette, Gizlice Ziya. Language Spoken and Differences in Health Status, Access to Care, and Receipt of Preventive Services Among US Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021–2028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley Donald J, Drake Joan, Quinlan Jennifer, Holden Alan, Saegert Pam, Karnad Anand, Ramirez Amelie. Beneficial Effects of a Combined Navigator/Promotora Approach for Hispanic Women Diagnosed with Breast Abnormalities. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21(10):1639–1644. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa de los Monteros Karla, Gallo LindaC. The Relevance of Fatalism in the Study of Latinas’ Cancer Screening Behavior: A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;18(4):310–318. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facione Noreen C, Miaskowski Christine, Dodd Marylin J, Paul Steven M. The Self-Reported Likelihood of Patient Delay in Breast Cancer: New Thoughts for Early Detection. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34(4):397–407. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0998. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedewa Stacey A, Ward Elizabeth M, Stewart Andrew K, Edge Stephen B. Delays in Adjuvant Chemotherapy Treatment Among Patients With Breast Cancer Are More Likely in African American and Hispanic Populations: A National Cohort Study, 2004–2006. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010 doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Harold P. Poverty, Culture, and Social Injustice: Determinants of Cancer Disparities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004;54(2):72–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo Linda C, Matthews Karen A. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(1):10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo Linda C, Penedo Frank J, Espinosa de los Monteros Karla, Arguelles William. Resiliency in the Face of Disadvantage: Do Hispanic Cultural Characteristics Protect Health Outcomes? Journal of Personality. 2009;77(6):1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getrich Christina M, Sussman Andrew L, Helitzer Deborah L, Hoffman Richard M, Warner Teddy D, Sánchez Victoria, Clinicians, on Behalf of RIOS Net Expressions of Machismo in Colorectal Cancer Screening Among New Mexico Hispanic Subpopulations. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(4):546–559. doi: 10.1177/1049732311424509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MA. Immigrant Adaptation and Patterns of Acculturation. Human Development. 2001;44(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Patricia, Castaneda Sheila F, Mills Paul J, Talavera Gregory A, Elder John P, Gallo Linda C. Determinants of Breast, Cervical and Colorectal Cancer Screening Adherence in Mexican–American Women. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37(2):421–433. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9459-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves Kristi D, Jensen Roxanne E, Cañar Janet, Perret-Gentil Monique, Leventhal Kara-Grace, Gonzalez Florencia, Mandelblatt Jeanne. Through the lens of culture: quality of life among Latina breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;136(2):603–613. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe Holly L, Wu Xiaocheng, Ries Lynn AG, Cokkinides Vilma, Ahmed Faruque, Jemal Ahmedin, Edwards Brenda K. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2003, featuring cancer among U.S. Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107(8):1711–1742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Daniel C, Leung Patrick, Naus Mary J. Using Single-System Analyses to Assess the Effectiveness of an Exercise Intervention on Quality of Life for Hispanic Breast Cancer Survivors: A Pilot Study. Social Work in Health Care. 2008;47(1):73–91. doi: 10.1080/00981380801970871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz Nancy K, Mujahid Mahasin S, Hawley Sarah T, Griggs Jennifer J, Hamilton Ann S, Katz Steven J. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(5):1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer Marjorie, Valdez Dadia Annalyn, Yu Mimi C, Surbone Antonella. Cancer, Culture, and Health Disparities: Time to Chart a New Course? CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60(1):12–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahende JW, Malarcher AM, Teplinskaya A, Asman KJ. Quit attempt correlates among smokers by race/ethnicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(10):3871–3888. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8103871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby James B, Liang Lan, Chen Hsin-Jen, Wang Youfa. Race, Place, and Obesity: The Complex Relationships Among Community Racial/Ethnic Composition, Individual Race/Ethnicity, and Obesity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(8):1572–1578. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski TL, Sonn G, Kwan L, Maliski S, Fink A, Litwin MS. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan Marilyn L, John Esther M, Caan Bette J, Lee Valerie S, Bernstein Leslie, Cheng Iona, Wu Anna H. Obesity and Mortality After Breast Cancer by Race/Ethnicity: The California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;179(1):95–111. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Medina Fernando, Pérez-Sánchez Víctor, Saavedra-Pérez David, Blake-Cerda Monika, Arce Claudia, Motola-Kuba Daniel, Arrieta Óscar. Triple-negative breast cancer in Hispanic patients. Cancer. 2011;117(16):3658–3669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss David T, Baker David W. Understanding Current Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening in the United States: The Contribution of Socioeconomic Status and Access to Care. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(3):228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class Maria, Castro Felipe González, Ramirez Amelie G. Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(9):1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.011. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class Maria, Perret-Gentil Monique, Kreling Barbara, Caicedo Larisa, Mandelblatt Jeanne, Graves KristiD. Quality of Life Among Immigrant Latina Breast Cancer Survivors: Realities of Culture and Enhancing Cancer Care. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26(4):724–733. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0249-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-McKee Gloria, McNeill Jeanette A, Bader Julia, Morales Pat. Comparison of factors affecting repeat mammography screening of low-income Mexican American women. Oncology nursing forum. 2008;35(6):941–947. doi: 10.1188/08.onf.941-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett Tim, Goldstein David, Butow Phyllis N, Gebski Val, Aldridge Lynley J, McGrane Joshua, King Madeleine T. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(13):1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macartney Suzanne, Bishaw Alemayehu, Fontenot Kayla. Poverty Rates for Selected Detailed Race and Hispanic Groups by State and Place: 2007–2011. 2013 Retrieved September 1, 2015, from https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acsbr11-17.pdf.

- Maly Rose C, Stein Judith A, Umezawa Yoshiko, Leake Barbara, Anglin M Douglas. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: Effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychology. 2008;27(6):728–736. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann Lilli, Foley Kristie L, Tanner Amanda E, Sun Christina J, Rhodes Scott D. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among US Hispanics/Latinas: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Cancer Education. 2015;30(2):374–387. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin Gerardo, Marin Barbara VanOss. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz Beth E, Richardson Jean, Hudson Sharon, Leedham Beth. Ethnicity and cancer outcomes: Behavioral and psychosocial considerations. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;123(1):47–70. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moadel Alyson B, Morgan Carole, Dutcher Janice. Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer. 2007;109(S2):446–454. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina Yamile, Thompson Beti, Espinoza Noah, Ceballos Rachel. Breast cancer interventions serving US-based Latinas: current approaches and directions. Women’s Health. 2013;9(4):335–350. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moralez Ernesto A, Rao Satya P, Livaudais Jennifer C, Thompson Beti. Improving Knowledge and Screening for Colorectal Cancer Among Hispanics: Overcoming Barriers Through a PROMOTORA-Led Home-Based Educational Intervention. Journal of Cancer Education. 2012;27(3):533–539. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Hector F. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoles AM, Ortiz C, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL, Gregorich S, Lee HE, Luce J. Nuevo Amanecer: results of a randomized controlled trial of a community-based, peer-delivered stress management intervention to improve quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e55–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel Manali I, Schupp Clayton W, Gomez Scarlett L, Chang Ellen T, Wakelee Heather A. How Do Social Factors Explain Outcomes in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Among Hispanics in California? Explaining the Hispanic Paradox. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(28):3572–3578. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.48.6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo Dahn, Jason R, Shen Biing-Jiun, Schneiderman Neil, Antoni Michael H. Ethnicity and determinants of quality of life after prostate cancer treatment. Urology. 2006;67(5):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.019. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo Frank J, Traeger Lara, Dahn Jason, Molton Ivan, Gonzalez JeffreyS, Schneiderman Neil, Antoni MichaelH. Cognitive behavioral stress management intervention improves quality of life in spanish monolingual hispanic men treated for localized prostate cancer: Results of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;14(3):164–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney Jean S, Ong Anthony D. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(3):271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro Paulo S, Sherman Recinda L, Trapido Edward J, Fleming Lora E, Huang Youjie, Gomez-Marin Orlando, Lee David. Cancer Incidence in First Generation U.S. Hispanics: Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and New Latinos. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(8):2162–2169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe Barbara D, Finnie Ramona. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(6):454–467. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe Barbara D. Fatalism among elderly African Americans: Effects on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Nursing. 1995;18(5):385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Amelie, Perez-Stable Eliseo, Penedo Frank, Talavera Gregory, Carrillo J Emilio, Fernández María, Gallion Kipling. Reducing time-to-treatment in underserved Latinas with breast cancer: The Six Cities Study. Cancer. 2014;120(5):752–760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes Scott D, Foley Kristie Long, Zometa Carlos S, Bloom Fred R. Lay Health Advisor Interventions Among Hispanics/Latinos: A Qualitative Systematic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(5):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ramos Zully A, Buki Lydia P. I will no longer be a man! Manliness and prostate cancer screenings among Latino men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2011;12(1):13–25. doi: 10.1037/a0020624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Michael A, Ward Lisa M, Pérez-Stable Eliseo J. Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening: Impact of Health Insurance Status, Ethnicity, and Nativity of Latinas. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(3):235–241. doi: 10.1370/afm.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkissyan Marianna, Wu Yanyuan, Vadgama Jaydutt V. Obesity is associated with breast cancer in African-American women but not Hispanic women in South Los Angeles. Cancer. 2011;117(16):3814–3823. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz Kathryn H, Agurs-Collins Tanya, Neuhouser Marian L, Pollack Lisa, Gehlert Sarah. Impact of Obesity, Race, and Ethnicity on Cancer Survivorship. In: Bowen DJ, Denis GV, Berger NA, editors. Impact of Energy Balance on Cancer Disparities. Vol. 9. Springer International Publishing; 2014. pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schootman Mario, Jeffe Donna B, Baker Elizabeth A, Walker Mark S. Effect of area poverty rate on cancer screening across US communities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(3):202–207. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah Mona, Zhu Kangmin, Potter John. Hispanic acculturation and utilization of colorectal cancer screening in the United States. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2006;30(3):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.04.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cdp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinfeld Gorin Sherri, Heck Julia E. Cancer screening among Latino subgroups in the United States. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40(5):515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.031. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Lebrun LA, Zhu J, Tsai J. Cancer screening among racial/ethnic and insurance groups in the United States: a comparison of disparities in 2000 and 2008. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(3):945–961. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Gopal K, Hiatt Robert A. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35(4):903–919. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery Martha L, Sweeney Carol, Edwards Sandra, Herrick Jennifer, Baumgartner Kathy, Wolff Roger, Byers Tim. Body size, weight change, fat distribution and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2007;102(1):85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9292-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Megan V, Ramsay Christina, Mazure Carolyn M. Understanding Disparities in Subpopulations of Women Who Smoke. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1(1):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s40429-013-0002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens Cristina, Stein Kevin, Landrine Hope. The role of acculturation in life satisfaction among Hispanic cancer survivors: results of the American Cancer Society’s study of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(4):376–383. doi: 10.1002/pon.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuné-Boyle Ingela C, Stygall Jan A, Keshtgar Mohammed R, Newman Stanton P. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(1):151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad Dennis R, Pérez-Stable Eliseo J, White Martha M, Emery Sherry L, Messer Karen. A Nationwide Analysis of US Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Smoking Behaviors, Smoking Cessation, and Cessation-Related Factors. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(4):699–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Overweight and Obesity Statistics. 2012 Retrieved September 1, 2015, from http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Documents/stat904z.pdf.

- Varela Alejandro, Jandorf Lina, DuHamel Katherine. Understanding Factors Related to Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening Among Urban Hispanics: Use of Focus Group Methodology. Journal of Cancer Education. 2010;25(1):70–75. doi: 10.1007/s13187-009-0015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallington SherrieFlynt, Luta Gheorghe, Noone Anne-Michelle, Caicedo Larisa, Lopez-Class Maria, Sheppard Vanessa, Mandelblatt Jeanne. Assessing the Awareness of and Willingness to Participate in Cancer Clinical Trials Among Immigrant Latinos. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37(2):335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9450-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Judith ME, Kaplan Celia P, Nguyen Bang, Gildengorin Ginny, McPhee Stephen J, Pérez-Stable Eliseo J. Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(2):156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward Elizabeth, Jemal Ahmedin, Cokkinides Vilma, Singh Gopal K, Cardinez Cheryll, Ghafoor Asma, Thun Michael. Cancer Disparities by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KJ, Roetzheim RG. Health disparities in receipt of screening mammography in Latinas: a critical review of recent literature. Cancer control: journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2007;14(4):369–379. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenten Madé, Gilliland Frank D, Baumgartner Kathy, Samet Jonathan M. Associations of Weight, Weight Change, and Body Mass with Breast Cancer Risk in Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Women. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12(6):435–444. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00293-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Kami K, Park Song-Yi, Kolonel Laurence N, Henderson Brian E, Wilkens Lynne R. Body size and breast cancer risk: The multiethnic cohort. International Journal of Cancer. 2012;131(5):E705–E716. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildes Kimberly A, Miller Alexander R, de Majors Sandra San Miguel, Ramirez Amelie G. The religiosity/spirituality of Latina breast cancer survivors and influence on health-related quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(8):831–840. doi: 10.1002/pon.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Melisa L, Clarke Christina A, Yang Juan, Hwang Jimmy, Hiatt Robert A, Wang Sunny. Incidence of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer among California Hispanics According to Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8(3):287–294. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827bd7f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez Betina, Stanton Annette L, Maly Rose C. Breast cancer treatment decision making among Latinas and non-Latina whites: A communication model predicting decisional outcomes and quality of life. Health Psychology. 2012;31(5):552–561. doi: 10.1037/a0028629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez Betina, Thompson Elizabeth H, Stanton Annette L. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonderman Alan B, Ejiogu Ngozi, Norbeck Jennifer, Evans Michele K. The Influence of Health Disparities on Targeting Cancer Prevention Efforts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(3, Supplement 1):S87–S97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.026. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]