Abstract

Background

Prucalopride, a selective, high-affinity 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist, stimulates gastrointestinal and colonic motility and alleviates common symptoms of chronic constipation (CC) in adults. The relative efficacy by gender has not been evaluated.

Aim

To evaluate the global efficacy and safety of prucalopride 2 mg daily in men and women with CC using data from six large, randomized, controlled clinical trials.

Methods

Data were combined from six phase 3 and 4, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials. The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients with a mean of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs) per week over 12 weeks of treatment. Safety was assessed throughout all the trials.

Results

Overall, 2484 patients (597 men; 1887 women; prucalopride, 1237; placebo, 1247) were included in the integrated efficacy analysis and 2552 patients were included in the integrated safety analysis. Significantly more patients achieved a mean of ≥3 SCBMs/week over the 12 weeks of treatment in the prucalopride group (27.8 %) than in the placebo group [13.2 %, OR 2.68 (95 % CI 2.16, 3.33), p < 0.001]. Prucalopride had a favorable safety and tolerability profile. Efficacy and safety outcomes were not significantly different between men and women.

Conclusion

The integrated analysis demonstrates the efficacy and safety of prucalopride in the treatment of CC in men and women.

Keywords: Constipation, Prucalopride, Efficacy, Safety

Introduction

Chronic constipation (CC) is a common disorder that can significantly impair an individual’s health-related quality of life [1] and work productivity [2]. Although laxatives may provide short-term symptom relief [3], most currently available laxatives do not directly target the underlying causes of constipation, such as lack of effective propulsive contractile activity possibly related to impaired intrinsic neural mechanisms [4–9], and are unable to provide relief from associated symptoms such as bloating, incomplete evacuation, and lumpy or hard stools [10]. Unfortunately, device-based treatments, such as those that stimulate the sacral nerve, have not been efficacious [11], but there are several pharmacological treatment options for patients with CC [12]. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonists have been shown to be effective in enhancing propulsive intestinal motility [13]; however, non-selective agents such as cisapride and tegaserod have been associated with adverse cardiovascular events, possibly owing to interaction with other 5-HT receptors [14]. Prolongation of the QT interval has been associated with interaction between 5-HT4 receptor agonists and human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channels [15]. Prucalopride is a selective, high-affinity 5-HT4 receptor agonist that does not exhibit a clinically relevant affinity for hERG channels [15, 16].

Prucalopride has been approved in the European Union for the symptomatic treatment of CC in adults in whom laxatives have failed to provide adequate relief [17]. The efficacy and safety of prucalopride has been investigated in five large phase 3 trials and one phase 4 trial in patients with CC [18–23]. In this integrated analysis, the efficacy and safety of prucalopride at doses of up to 2 mg/day was evaluated across all six clinical trials in both genders. Analysis of this large pooled data set provides an overview of the efficacy and safety of prucalopride in both men and women across four continents. This analysis also aims to compare the treatment response and safety of prucalopride in men versus women, and to investigate the response in individuals with severe CC at baseline.

Methods

This integrated analysis of efficacy and safety was performed using combined data from six phase 3 and 4, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials performed across three continents [ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: SPD555-302 (NCT01147926), SPD555-401 (NCT01424228), PRU-CRC-3001 (NCT01116206), PRU-USA-13 (NCT00485940), PRU-USA-11 (NCT00483886), and PRU-INT-6 (NCT00488137)]. These trials were approved by independent Institutional Review Boards or independent Ethics Committees and were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. Patients provided written informed consent before entering the trials.

The study designs of these trials were similar (Table 1) and have been described in further detail in the published literature [18–23]. All trials included adult patients with CC [defined as ≤2 spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) per week for at least 6 months]. In addition, participants had to have hard or very hard stools, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, or straining during defecation in at least 25 % of bowel movements (BMs). Patients were excluded if they were considered to have drug-induced constipation, or constipation secondary to causes such as endocrine, metabolic, or neurological disorders, or surgery. The doses of prucalopride used in the trials varied from 1 to 4 mg/day; the approved 2 mg/day dose was evaluated in all of the trials (Table 1). Only patients receiving prucalopride 2 mg/day and the few individuals who received prucalopride 1 mg/day throughout a trial were included in this integrated analysis.

Table 1.

Description of the six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials

| Study ID | Number of study centers and location | Trial dates | Daily drug dosea | Number of patients assigned to each treatment arm | Duration, weeks | Sex, men/women | Median age, years (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPD555-302 [23] | 66 Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Netherlands, UK |

September 23, 2010–October 25, 2013 | Prucalopride 2 mg or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 177 Prucalopride 1 mg: 80 (65 increased to 2 mg) Placebo: 181 |

12 | 370/0 | 61.0 (18–91) |

| SPD555-401 [22] | 50 Belgium, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden |

April 6, 2011–December 19, 2012 | Prucalopride 2 mg or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 171 Prucalopride 1 mg: 35 (28 increased to 2 mg) Placebo: 169 |

24 | 53/308 | 50.0 (18–91) |

| PRU-CRC-3001 [21] | 46 Australia, China, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand |

April 2, 2010–March 9, 2011 | Prucalopride 2 mg or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 249 Placebo: 252 |

12 | 51/450 | 43.0 (18–65) |

| PRU-USA-13 [20] | 41 USA |

March 18, 1998–May 4, 1999 | Prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg, or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 214 Prucalopride 4 mg: 215b Placebo: 212 |

12 | 86/555 | 46.0 (18–95) |

| PRU-USA-11 [18] | 38 USA |

April 2, 1998–May 24, 1999 | Prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg, or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 190 Prucalopride 4 mg: 204b Placebo: 193 |

12 | 75/545 | 47.5 (18–85) |

| PRU-INT-6 [19] | 63 Australia, Belgium, Canada, Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, UK |

March 13, 1998–July 19, 1999 | Prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg, or placebo | Prucalopride 2 mg: 236 Prucalopride 4 mg: 238b Placebo: 240 |

12 | 66/650 | 43.0 (17–89) |

The primary endpoint for each trial was the proportion of patients with ≥3 SCBMs/week over the duration of the trial

SCBM spontaneous complete bowel movement

aPrucalopride and placebo administered as oral tablets

bPatients receiving prucalopride 4 mg were not included in the integrated analysis

Efficacy

In each of the six trials, efficacy data were collected from patient diaries that recorded medication intake, stool frequency, and stool characteristics on a daily basis throughout the treatment period.

The primary efficacy endpoint for this integrated analysis was the percentage of patients with a mean frequency of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs) per week over weeks 1–12.

The secondary efficacy endpoints included the following: BM frequency; stool characteristics; time to first BM; rescue medication use; Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms questionnaire (PAC-SYM) and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire (PAC-QOL) scores; and global severity of constipation and global efficacy of treatment scores. Bisacodyl was the protocol-specified rescue medication (laxative) used during each of the trials. We also assessed the mean number of tablets taken or enemas administered per week and the mean number of days on which any laxative was used.

In an exploratory analysis, the proportions of patients meeting the primary endpoint who had no SBMs at baseline were compared with those who had one or more SBM at baseline.

Safety

The following safety parameters were monitored throughout the trials: adverse events, clinical laboratory evaluations (hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis), electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters, and vital signs. Full details of the safety protocols are published elsewhere [18–23].

Statistical Analysis

Data from the six trials were combined. Statistical analyses and tests were performed on the combined efficacy data. Safety data were evaluated descriptively only. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). In studies SPD555-302 and SPD555-401, patients in the prucalopride group who were aged ≥65 years started on a daily dose of 1 mg, in line with the approved starting dose for this age group. However, the prucalopride dose was increased to 2 mg/day in the majority of these patients during the studies, so the results were combined into a single group (prucalopride ≤2 mg/day) for the current analysis.

Primary Endpoint

The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used to compare the effects of treatment on the primary endpoint. The analysis was stratified by study number, number of complete bowel movements (CBMs) per week at baseline (0 or >0), geographical region, and sex. All tests were performed at a 5 % level of significance. Odds ratios [with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs)] for each trial were derived and presented in a forest plot. Inconsistency between trials was evaluated using the I2 statistic and the Breslow–Day test [24].

Data Imputation for Primary Endpoint

To evaluate the impact of missing data (as a result of early discontinuation of treatment), three sensitivity analyses were conducted for the primary efficacy endpoint: (a) a generalized linear mixed model for repeated measures (including factors for treatment group, week, and treatment group × week); (b) a multiple imputation model using on-treatment data; and (c) a multiple imputation model using placebo data.

Secondary Endpoints

Secondary efficacy endpoints were assessed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment group, study number, number of CBMs per week at baseline (0 or >0), geographical region, and sex as factors and the baseline value of the outcome as a covariate. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to compare the time to first SBM and the time to first SCBM in the prucalopride group versus the placebo group. The model included terms for treatment group, study number, number of CBMs per week at baseline (0 or >0), geographical region, and sex. Hazard ratios and the respective 95 % CIs and p values were obtained for each treatment group comparison.

For PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL, descriptive statistics (actual values and changes from baseline) for the total score and subscale scores were performed at baseline and at various time points during treatment. Similarly, descriptive statistics were reported for global severity of constipation (0 = absent to 4 = very severe) and global efficacy of treatment (0 = not at all effective to 4 = extremely effective).

The ANCOVA model used to compare treatment effects included treatment group, study number, number of CBMs per week at baseline (0 or >0), geographical region, and sex as factors, and the baseline value of the outcome as a covariate. PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL total scores and subscale scores were also summarized by categories of improvement (<1 point and ≥1-point of improvement from baseline) and by treatment group. No statistical testing was performed on these summaries.

Exploratory Analysis

The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used to compare the proportions of patients meeting the primary endpoint who had no SBMs at baseline with those who had one or more SBMs at baseline.

Results

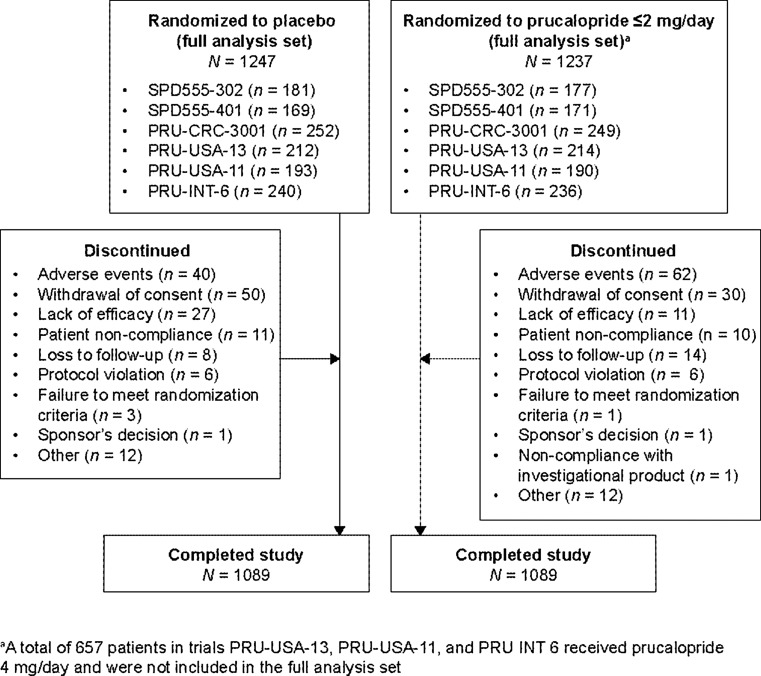

Overall, 2484 patients [597 (24 %) men] were included in the integrated efficacy analysis: 1247 patients [300 (24 %) men] received placebo and 1237 patients [297 (24 %) men] received prucalopride ≤2 mg (Fig. 1; Table 2). The majority of patients [2178 (87.7 %)] completed 12 weeks of treatment. The main reasons for study discontinuation were adverse events (4.1 %), withdrawal of consent (3.2 %), and lack of efficacy (1.5 %).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics of the pooled patient population (efficacy analysis)

| Characteristic | Placebo N = 1247 |

Prucalopride ≤2 mg N = 1237 |

Overall N = 2484 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 47.4 (15.3) | 47.5 (15.8) | 47.4 (15.6) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 47.0 (18, 91) | 46.0 (17, 95) | 47.0 (17, 95) |

| Age, n (%) | |||

| <65 years | 1069 (85.7) | 1041 (84.2) | 2110 (84.9) |

| ≥65 years | 178 (14.3) | 196 (15.8) | 374 (15.1) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 300 (24.1) | 297 (24.0) | 597 (24.0) |

| Women | 947 (75.9) | 940 (76.0) | 1887 (76.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 951 (76.3) | 925 (74.8) | 1876 (75.5) |

| Non-Caucasian | 287 (23.0) | 303 (24.5) | 590 (23.8) |

| Missing | 9 (<1.0) | 9 (<1.0) | 18 (<1.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.8 (4.8) | 25.1 (4.7) | 25.0 (4.8) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 24.0 (16, 65) | 24.5 (15, 57) | 24.2 (14, 65) |

| Duration of constipation, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.5 (14.5) | 16.5 (14.8) | 16.5 (14.6) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 12.0 (1, 77) | 10.2 (1, 70) | 11.0 (1, 77) |

| Duration of constipation, years, n (%) | |||

| <1 | 42 (3.4) | 33 (2.7) | 75 (3.0) |

| 1–<5 | 253 (20.3) | 272 (22.0) | 525 (21.1) |

| 5–<10 | 179 (14.4) | 157 (12.7) | 336 (13.5) |

| 10–<15 | 170 (13.6) | 202 (16.3) | 372 (15.0) |

| 15–<20 | 98 (7.9) | 101 (8.2) | 199 (8.0) |

| ≥20 | 469 (37.6) | 436 (35.2) | 905 (36.4) |

| Missing | 36 (2.9) | 36 (2.9) | 72 (2.9) |

| Main complaint, n (%) | |||

| Infrequent defecation | 315 (25.3) | 327 (26.4) | 642 (25.8) |

| Abdominal bloating | 263 (21.1) | 239 (19.3) | 502 (20.2) |

| Feeling of incomplete evacuation | 205 (16.4) | 212 (17.1) | 417 (16.8) |

| Straining | 185 (14.8) | 174 (14.1) | 359 (14.5) |

| Abdominal pain | 161 (12.9) | 162 (13.1) | 323 (13.0) |

| Hard stools | 118 (9.5) | 122 (9.9) | 240 (9.7) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (<1.0) | 1 (<1.0) |

| SBMs/week during the last 6 months, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 361 (28.9) | 385 (31.1) | 746 (30.0) |

| >0–≤1 | 394 (31.6) | 399 (32.3) | 793 (31.9) |

| >1–≤3 | 471 (37.8) | 433 (35.0) | 904 (36.4) |

| >3 | 21 (1.7) | 20 (1.6) | 41 (1.7) |

| Stools that are hard or very hard, n (%) | |||

| 0–25 | 125 (10.0) | 132 (10.7) | 257 (10.3) |

| 26–50 | 188 (15.1) | 171 (13.8) | 359 (14.5) |

| 51–75 | 253 (20.3) | 248 (20.0) | 501 (20.2) |

| 76–100 | 512 (41.1) | 514 (41.6) | 1026 (41.3) |

| Missing | 169 (13.6) | 172 (13.9) | 341 (13.7) |

| Diet adjusted, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 684 (54.9) | 683 (55.2) | 1367 (55.0) |

| No | 563 (45.1) | 554 (44.8) | 1117 (45.0) |

| Previous use of laxativesa, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 867 (69.5) | 873 (70.6) | 1740 (70.0) |

| No | 380 (30.5) | 364 (29.4) | 744 (30.0) |

| Previous use of bulk-forming laxativesa, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 523 (41.9) | 506 (40.9) | 1029 (41.4) |

| No | 724 (58.1) | 731 (59.1) | 1455 (58.6) |

| Overall therapeutic effect of laxatives/bulk-forming agents, n (%) | |||

| Adequate | 191 (15.3) | 198 (16.0) | 389 (15.7) |

| Inadequate | 907 (72.7) | 904 (73.1) | 1811 (72.9) |

| Missing | 149 (11.9) | 135 (10.9) | 284 (11.4) |

BMI body mass index, SBM spontaneous bowel movement, SD standard deviation

aIn trial SPD555-401, these data were collected as part of prior and concomitant medications (no specific questions were asked); in the other double-blind, placebo-controlled studies this was part of the baseline disease characteristics information (specific yes/no questions were asked)

An overview of the demographics and baseline disease characteristics of patients included in the integrated efficacy population is presented in Table 2. Most patients were Caucasian (75.5 %), and the mean [standard deviation (SD)] age was 47.4 (15.6) years. The mean (SD) duration of constipation was 16.5 (14.6) years. Overall, 30.0 % of patients had no SBMs at baseline, consistent with severe constipation. Demographics and baseline disease characteristics were similar in the prucalopride and placebo groups. However, there were some differences in demographics and baseline disease characteristics between men and women (Table 3). Women were older on average than men [56.3 (16.7) vs 45.0 (14.0) years], and the mean duration of constipation was longer for women than for men [18.8 (15.0) vs 11.6 (13.9) years]. There were also differences between men and women in the frequencies of the main complains reported at baseline; while the most common main complaint in men and in women was infrequent defecation (23.6 and 26.6 %, respectively), the second most frequent main complaint was feeling not completely empty in men (22.3 %), whereas in women it was abdominal bloating (22.7 %).

Table 3.

Baseline disease characteristics of the pooled patient population analyzed by sex (efficacy analysis)

| Characteristic | Placebo | Prucalopride ≤2 mg/day | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women N = 947 |

Men N = 300 |

Women N = 940 |

Men N = 297 |

Women N = 1887 |

Men N = 597 |

|

| Main complaint, n (%) | ||||||

| Abdominal bloating | 224 (23.7) | 39 (13.0) | 204 (21.7) | 35 (11.8) | 428 (22.7) | 74 (12.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 132 (13.9) | 29 (9.7) | 139 (14.8) | 23 (7.7) | 271 (14.4) | 52 (8.7) |

| Feeling not completely empty | 150 (15.8) | 55 (18.3) | 134 (14.3) | 78 (26.3) | 284 (15.1) | 133 (22.3) |

| Hard stools | 83 (8.8) | 35 (11.7) | 86 (9.1) | 36 (12.1) | 169 (9.0) | 71 (11.9) |

| Infrequent defecation | 240 (25.3) | 75 (25.0) | 261 (27.8) | 66 (22.2) | 501 (26.6) | 141 (23.6) |

| Straining | 118 (12.5) | 67 (22.3) | 116 (12.3) | 58 (19.5) | 234 (12.4) | 125 (20.9) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1.0) | 0 | 1 (<1.0) |

| Diet adjusted, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 521 (55.0) | 163 (54.3) | 510 (54.3) | 173 (58.2) | 1031 (54.6) | 336 (56.3) |

| No | 426 (45.0) | 137 (45.7) | 430 (45.7) | 124 (41.8) | 856 (45.4) | 261 (43.7) |

| Previous use of laxativesa, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 677 (71.5) | 190 (63.3) | 683 (72.7) | 190 (64.0) | 1360 (72.1) | 380 (63.7) |

| No | 270 (28.5) | 110 (36.7) | 257 (27.3) | 107 (36.0) | 527 (27.9) | 217 (36.3) |

| Previous use of bulk-forming laxativesa, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 421 (44.5) | 102 (34.0) | 405 (43.1) | 101 (34.0) | 826 (43.8) | 203 (34.0) |

| No | 526 (55.5) | 198 (66.0) | 535 (56.9) | 196 (66.0) | 1061 (56.2) | 394 (66.0) |

| SCBMs/week during the past 6 months, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 321 (33.9) | 40 (13.3) | 329 (35.0) | 56 (18.9) | 650 (34.4) | 96 (16.1) |

| >0–≤1 | 310 (32.7) | 84 (28.0) | 309 (32.9) | 90 (30.3) | 619 (32.8) | 174 (29.1) |

| >1–≤3 | 308 (32.5) | 163 (54.3) | 294 (31.3) | 139 (46.8) | 602 (31.9) | 302 (50.6) |

| >3 | 8 (<1.0) | 13 (4.3) | 8 (<1.0) | 12 (4.0) | 16 (<1.0) | 25 (4.2) |

| Stools that are hard or very hard, n (%) | ||||||

| 0–25 | 103 (10.9) | 22 (7.3) | 107 (11.4) | 25 (8.4) | 210 (11.1) | 47 (7.9) |

| 26–50 | 114 (12.0) | 74 (24.7) | 114 (12.1) | 57 (19.2) | 228 (12.1) | 131 (21.9) |

| 51–75 | 175 (18.5) | 78 (26.0) | 165 (17.6) | 83 (27.9) | 340 (18.0) | 161 (27.0) |

| 76–100 | 411 (43.4) | 101 (33.7) | 407 (43.3) | 107 (36.0) | 818 (43.3) | 208 (34.8) |

| Missing | 144 (15.2) | 25 (8.3) | 147 (15.6) | 25 (8.4) | 291 (15.4) | 50 (8.4) |

| Overall therapeutic effect, n (%) | ||||||

| Adequate | 159 (16.8) | 32 (10.7) | 162 (17.2) | 36 (12.1) | 321 (17.0) | 68 (11.4) |

| Inadequate | 672 (71.0) | 235 (78.3) | 679 (72.2) | 225 (75.8) | 1351 (71.6) | 460 (77.1) |

| Missing | 116 (12.2) | 33 (11.0) | 99 (10.5) | 36 (12.1) | 215 (11.4) | 69 (11.6) |

SCBM spontaneous complete bowel movement

aIn trial SPD555-401, these data were collected as part of prior and concomitant medications (no specific questions were asked); in the other double-blind, placebo-controlled studies this was part of the baseline disease characteristics information (specific yes/no questions were asked)

Primary Efficacy Results

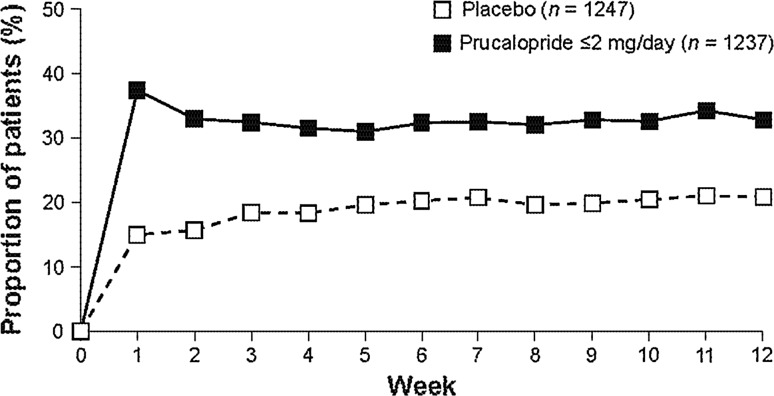

Overall, the percentage of patients with a mean frequency of ≥3 SCBMs/week over the 12-week treatment period was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the prucalopride group (27.8 %) than the placebo group (13.2 %). The difference in response rate between groups (the therapeutic gain) was 14.6 %. The placebo response ranged from 9.6 % (PRU-INT-6) to 20.1 % (SPD555-401), and the response to prucalopride ranged from 19.5 % (PRU-INT-6) to 37.9 % (SPD555-302). During each individual week from week 1 to week 12, the proportion of patients with ≥3 SCBMs was always higher in the prucalopride group than in the placebo group, with no evidence of decreasing efficacy over time (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients in the pooled population with a mean frequency of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements/week over the 12-week treatment period, by individual weekly period

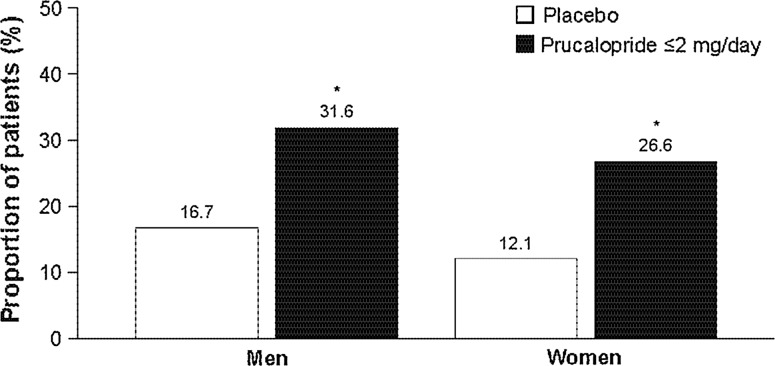

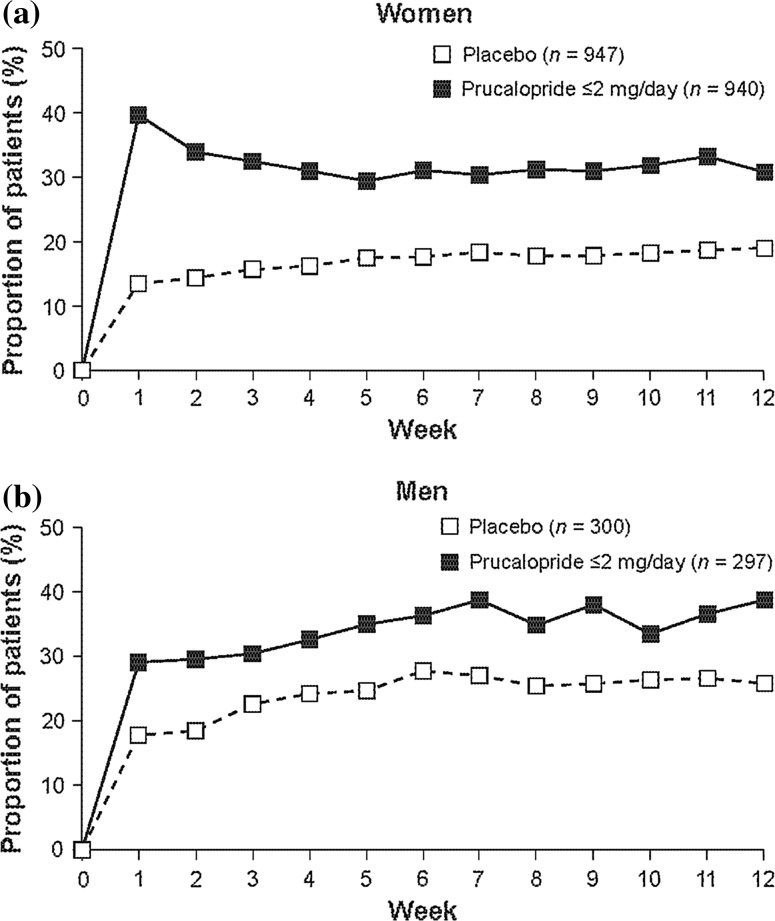

Results were consistent when analyzed by sex, with the therapeutic gain being similar in men (15.0 %) and women (14.5 %) for the primary efficacy endpoint (both p < 0.001 for the comparison of prucalopride vs placebo) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with ≥3 SCBMs/week was consistently higher in each of weeks 1–12 in the prucalopride group than in the placebo group in both men and women (Fig. 4). Interestingly, women had a peak in response rate at week 1, which subsequently stabilized over the 12 weeks, whereas the response rate for men improved slightly over weeks 1–12 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients in the pooled population with a mean frequency of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week over the 1–12-week treatment period analyzed by sex. *p < 0.001 versus placebo

Fig. 4.

Proportion of a women and b men in the pooled population with a mean frequency of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week over the 12-week treatment period analyzed by individual weekly period

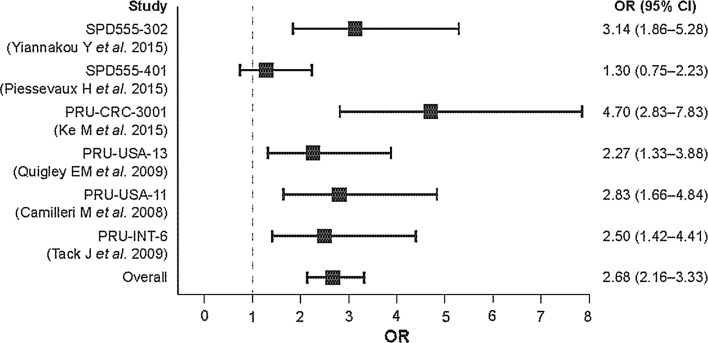

A forest plot comparing prucalopride with placebo for the primary efficacy endpoint for each of the six clinical trials and for the integrated (overall) population is presented in Fig. 5. The overall odds ratio was 2.68 (95 % CI 2.16–3.33). The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve the primary efficacy endpoint in one patient in the prucalopride group was 8.8 (95 % CI 7.1–11.6).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot comparing prucalopride with placebo for a frequency of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week for each of the phase 3 and 4 clinical trials and for the integrated (pooled) patient population. Breslow–Day test for inconsistency of response rates between studies resulted in a p value of 0.0406 and an I 2 statistic of 56 %, indicating a moderate heterogeneity. CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Sensitivity Analyses

The results of three sensitivity analyses carried out for the primary endpoint were consistent with the results of the original analysis. The odds ratios (95 % CI) were 2.39 (2.16–2.65), 2.81 (2.27–3.48), and 2.77 (2.24–3.42) for the generalized mixed model, the on-treatment multiple imputation model, and the placebo multiple imputation model, respectively (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Heterogeneity

The Breslow–Day test for inconsistency of response rates across trials resulted in a p value of 0.0406 and an I2 statistic of 56 %, indicating moderate heterogeneity. This heterogeneity was due to the results of the SPD555-401 trial [22], which was conducted over 24 weeks as opposed to 12 weeks. If these data were excluded, the I2 statistic was 6.8 %, indicating no heterogeneity across the other five clinical trials.

Secondary Efficacy Results

An overview of the main secondary efficacy endpoints is presented in Table 4. There were significantly beneficial results for the prucalopride group compared with the placebo group in the following outcomes: the proportion of patients with a mean increase of ≥1 SCBM/week over the 12-week treatment period; the median time to first SCBM after intake of investigational product on day 1; the decrease in mean number of tablets of rescue medication taken per week; the decrease in mean number of days of rescue medication use over 12 weeks of treatment; the mean improvement in PAC-SYM total score from baseline to the final on-treatment assessment (with similar findings observed for the stool, abdominal, and rectal symptom subscale scores); and the mean improvement in PAC-QOL total score from baseline to final on-treatment assessment. The proportions of patients with an improvement of ≥1 point in the PAC-QOL subscale scores are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Overview of the main secondary efficacy endpoints in the pooled patient population

| Endpoint | Time period | Placebo N = 1247 |

Prucalopride ≤2 mg N = 1237 |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a | Value | N a | Value | |||

| Increase in SCBM frequency, n (%) | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with a mean increase of ≥1 SCBM/week | Weeks 1–12 | 1247 | 373 (29.9) | 1237 | 582 (47.0) | <0.001b |

| Stool characteristics | ||||||

| Proportion of stools with normal consistency, mean % | Run-in | 1238 | 25.1 | 1230 | 24.9 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1214 | 38.5 | 1181 | 43.3 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with hard to very hard consistency, mean % | Run-in | 1238 | 45.5 | 1230 | 45.3 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1214 | 34.3 | 1181 | 25.4 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with no straining, mean % | Run-in | 1238 | 15.1 | 1230 | 15.3 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1214 | 16.6 | 1181 | 20.8 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with severe or very severe straining, mean % | Run-in | 1238 | 33.0 | 1230 | 34.1 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1214 | 24.8 | 1181 | 18.8 | NA | |

| Time to first SCBM, days, median (95 % CI) | Time from day 1 | 1247 | 13.5 (12.0–16.0) | 1237 | 3.1 (2.5–3.7) | <0.001c |

| Rescue medication use, mean (mean change) | ||||||

| Number of laxatives (tablets) taken/week | Run-in | 1241 | 1.9 | 1232 | 1.8 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1150 | 1.5 (–0.3) | 1142 | 0.9 (–0.9) | <0.001d | |

| Number of days with rescue medication use/week | Run-in | 1241 | 1.0 | 1232 | 0.9 | |

| Weeks 1–12 | 1150 | 0.7 (–0.2) | 1142 | 0.4 (–0.5) | <0.001d | |

| PAC-SYM score, mean (mean change) | ||||||

| Total score | Baseline | 1240 | 1.9 | 1234 | 1.9 | |

| FoTA | 1228 | 1.4 (–0.4) | 1212 | 1.2 (–0.7) | <0.001d | |

| Stool symptoms | Baseline | 1239 | 2.4 | 1233 | 2.4 | |

| FoTA | 1228 | 1.9 (–0.5) | 1212 | 1.6 (–0.8) | <0.001d | |

| Abdominal symptoms | Baseline | 1240 | 1.8 | 1233 | 1.8 | |

| FoTA | 1227 | 1.3 (–0.4) | 1213 | 1.1 (–0.7) | <0.001d | |

| Rectal symptoms | Baseline | 1236 | 1.1 | 1232 | 1.2 | |

| FoTA | 1227 | 0.8 (–0.3) | 1212 | 0.7 (–0.5) | <0.001d | |

| PAC-SYM score, patients with an improvement of ≥1 point from baseline, n (%) | ||||||

| Total score | FoTA | 1221 | 292 (23.9) | 1209 | 402 (33.3) | NA |

| Stool symptoms | FoTA | 1220 | 395 (32.4) | 1208 | 526 (43.5) | NA |

| Abdominal symptoms | FoTA | 1220 | 344 (28.2) | 1209 | 460 (38.0) | NA |

| Rectal symptoms | FoTA | 1216 | 299 (24.6) | 1207 | 376 (31.2) | NA |

| PAC-QOL score, mean (mean change) | ||||||

| Total score | Baseline | 1238 | 2.1 | 1233 | 2.0 | |

| FoTA | 1210 | 1.6 (–0.5) | 1206 | 1.3 (–0.7) | <0.001d | |

| PAC-QOL score, patients with an improvement of ≥1 point from baseline, n (%) | ||||||

| Total score | FoTA | 1201 | 268 (22.3) | 1202 | 446 (37.1) | NA |

| Global assessment of severity of constipation, mean (mean change) | ||||||

| Baseline | 1236 | 2.7 | 1232 | 2.7 | ||

| 12 weeks | 1075 | 2.2 (–0.6) | 1078 | 1.7 (–1.0) | NA | |

| Global assessment of efficacy of treatment, mean | ||||||

| 12 weeks | 1075 | 1.3 | 1077 | 1.9 | NA | |

ANCOVA analysis of covariance, CBM complete bowel movement, CI confidence interval, FoTA final on-treatment assessment, NA not assessed, PAC-QOL Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire, PAC-SYM Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms questionnaire, SCBM spontaneous complete bowel movement

aNumber with data for each endpoint

b p value based on a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test controlling for study number, sex, geographical region, and number of CBMs/week at baseline

c p value based on a Cox proportional hazard regression including terms for treatment group, study number, geographical region, number of CBMs at baseline (0 or >0), and sex

d p value based on an ANCOVA model performed with study number, geographical region, number of CBMs/week during the run-in period (0 or >0), and sex as factors and the baseline value of the outcome as a covariate

Table 5.

Proportion of patients with an improvement of ≥1 point in the PAC-QOL subscale scores in the pooled population

| PAC-QOL subscale | Patients with an improvement of ≥1 point from baseline to final on-treatment assessment, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo N = 1247 |

Prucalopride ≤ 2 mg N = 1237 |

|||

| N a | Value | N a | Value | |

| Dissatisfaction | 1192 | 316 (26.5) | 1198 | 554 (46.2) |

| Physical discomfort | 1202 | 404 (33.6) | 1202 | 568 (47.3) |

| Psychosocial discomfort | 1196 | 267 (22.3) | 1201 | 327 (27.2) |

| Worries and concerns | 1198 | 314 (26.2) | 1201 | 474 (39.5) |

PAC-QOL Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire

aNumber with data for each endpoint

When analyzed by sex, results were generally similar in men and women (Table 6).

Table 6.

Overview of secondary efficacy endpoints analyzed by sex in the pooled patient population

| Endpoint | Time period | Placebo | Prucalopride ≤ 2 mg | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N = 947 | Men, N = 300 | Women, N = 940 | Men, N = 297 | ||||||||

| N a | Value | N a | Value | N a | Value | p value | N a | Value | p value | ||

| Increase in SCBM frequency, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Proportion of patients with a mean increase of ≥1 SCBM/week | Week 1–12 | 947 | 256 (27.0) | 300 | 117 (39.0) | 940 | 444 (47.2) | <0.001b | 297 | 138 (46.5) | 0.025b |

| Stool characteristic (mean %) | |||||||||||

| Proportion of stools with normal consistency | Run-in | 942 | 24.4 | 296 | 27.3 | 937 | 24.6 | NA | 293 | 25.8 | NA |

| Week 1–12 | 924 | 36.3 | 290 | 45.6 | 899 | 43.1 | NA | 282 | 44.1 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with hard to very hard consistency | Run-in | 942 | 44.6 | 296 | 48.5 | 937 | 43.4 | NA | 293 | 51.3 | NA |

| Week 1–12 | 924 | 35.4 | 290 | 30.9 | 899 | 25.3 | NA | 282 | 25.7 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with no straining | Run-in | 942 | 16.7 | 296 | 10.1 | 937 | 17.7 | NA | 293 | 7.5 | NA |

| Week 1–12 | 924 | 17.7 | 290 | 13.0 | 899 | 22.8 | NA | 282 | 14.2 | NA | |

| Proportion of stools with severe or very severe straining | Run-in | 942 | 32.6 | 296 | 34.3 | 937 | 32.0 | NA | 293 | 40.9 | NA |

| Week 1–12 | 924 | 25.7 | 290 | 21.9 | 899 | 18.5 | NA | 282 | 19.7 | NA | |

| Time to first SCBM, days, median (95 % CI) | Time from day 1 | 947 | 15.1 (12.7–18.2) | 300 | 9.6 (6.1–12.8) | 940 | 2.7 (2.3–3.3) | <0.001c | 297 | 4.6 (3.0–7.1) | <0.001c |

| Rescue medication use, mean (mean change) | |||||||||||

| Number of laxatives (tablets) taken/week | Run-in | 945 | 2.0 | 296 | 1.8 | 939 | 1.9 | 293 | 1.6 | ||

| Week 1–12 | 872 | 1.7 (–0.2) | 278 | 1.1 (–0.6) | 869 | 1.0 (–0.9) | <0.001d | 270 | 0.8 (–0.8) | 0.019d | |

| Number of days with rescue medication use/week | Run-in | 945 | 1.0 | 296 | 1.0 | 939 | 0.9 | 293 | 0.9 | ||

| Week 1–12 | 872 | 0.8 (–0.2) | 275 | 0.6 (–0.4) | 869 | 0.5 (–0.5) | <0.001d | 270 | 0.4 (–0.5) | 0.007d | |

| PAC-SYM score, mean (mean change) | |||||||||||

| Total score | Baseline | 944 | 1.9 | 296 | 1.7 | 939 | 1.9 | 295 | 1.8 | ||

| FoTA | 938 | 1.5 (–0.4) | 290 | 1.2 (–0.5) | 927 | 1.2 (–0.7) | <0.001d | 285 | 1.1 (–0.7) | 0.019d | |

| PAC-SYM score, patients with an improvement of ≥1 point from baseline, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Total score | FoTA | 935 | 222 (23.7) | 286 | 70 (24.5) | 926 | 314 (33.9) | NA | 283 | 88 (31.1) | NA |

| PAC-QOL score, mean (mean change) | |||||||||||

| Total score | Baseline | 941 | 2.1 | 297 | 1.9 | 938 | 2.1 | 295 | 1.9 | ||

| FoTA | 922 | 1.7 (–0.4) | 288 | 1.4 (–0.5) | 921 | 1.3 (–0.8) | <0.001d | 285 | 1.2 (–0.7) | 0.003d | |

| PAC-QOL score, patients with an improvement of ≥1 point from baseline, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Total score | FoTA | 916 | 190 (20.7) | 285 | 78 (27.4) | 919 | 346 (37.6) | NA | 283 | 100 (35.3) | NA |

ANCOVA analysis of covariance, CBM complete bowel movement, CI confidence interval, FoTA final on-treatment assessment, NA not available, PAC-QOL Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire, PAC-SYM Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms questionnaire, SCBM spontaneous complete bowel movement

aNumber with data for each endpoint

b p value based on a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test controlling for study number, sex, geographical region, and number of CBMs/week at baseline

c p value based on a Cox proportional hazard regression including terms for treatment group, study number, geographical region, number of CBMs at baseline (0 or >0), and sex

d p value based on an ANCOVA model performed with study number, country, number of CBMs/week (0 or >0) during the run-in period, and sex as factors and the baseline value of the outcome as a covariate

Exploratory Results

The odds ratio (95 % CI) for the proportion of patients with no SBMs at baseline meeting the primary endpoint [3.16 (2.24–4.46)] was greater than that for patients with one or more SBM at baseline [2.65 (1.98–3.55)]. However, the magnitude of the difference between the placebo and prucalopride groups in the proportion of patients meeting the primary endpoint was similar in both stratifications (mean therapeutic gain for no SBMs vs one or more SBM at baseline: 11.4 vs 15.1 %, respectively).

Safety

The overall mean (SD) duration of exposure was similar in the prucalopride [87.3 (35.1) days] and placebo [87.9 (33.0) days] groups.

Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics

Overall, a total of 2552 patients (618 men) were included in the integrated safety analysis; 1279 patients (309 men) received placebo and 1273 patients (309 men) received prucalopride ≤2 mg/day. The demographic characteristics were similar to those of the efficacy analysis population [78.2 % women, 79.5 % Caucasian, mean (SD) age 47.4 (15.2) years].

Adverse Events

A summary of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the pooled data set is presented in Table 7 by treatment group. Overall, 806 patients (63.3 %) in the prucalopride group and 682 patients (53.3 %) in the placebo group experienced ≥1 TEAE. The majority of TEAEs experienced by patients in both treatment groups were mild or moderate in severity. No fatal TEAEs occurred. The most common TEAEs (≥5 %) in the prucalopride group were gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain) and headache. Few patients reported cardiovascular adverse events (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of TEAEs in the pooled patient population

| TEAEs | Placebo, n (%) N = 1279 |

Prucalopride ≤ 2 mg/day, n (%) N = 1273 |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TEAE | 682 (53.3) | 806 (63.3) |

| TEAEs related to the investigational product | 272 (21.3) | 461 (36.2) |

| Mild TEAEs | 471 (36.8) | 585 (46.0) |

| Moderate TEAEs | 358 (28.0) | 418 (32.8) |

| Severe TEAEs | 113 (8.8) | 152 (11.9) |

| Serious TEAEs | 31 (2.4) | 21 (1.6) |

| Fatal TEAEs | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs leading to permanent discontinuation | 43 (3.4) | 66 (5.2) |

| TEAEs of cardiovascular interest | ||

| Angina pectoris | 1 (<0.1) | 0 |

| Unstable angina | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial ischemia | 1 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 | 1 (<0.1) |

| Ischemic stroke | 1 (<0.1) | 0 |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

Overall, fewer men than women reported ≥1 TEAE (prucalopride group, 47.2 vs 68.5 %; placebo group, 38.5 vs 58.0 %, respectively). The most common TEAEs were similar in both sexes, although the incidences of these TEAEs tended to be lower in men than women in both treatment groups (data not shown). Similar proportions of men and women reported TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation (women: 5.4 % receiving prucalopride, 3.2 % receiving placebo; men: 4.5 % receiving prucalopride, 3.9 % receiving placebo).

Clinical Laboratory Evaluations

Mean changes from baseline in biochemistry, hematology, and urinalysis parameters were generally small and were not considered to be clinically relevant (data not shown). The incidence of TEAEs related to laboratory test abnormalities was generally low and was similar in the prucalopride and placebo groups as well as in men and women (data not shown).

Vital Signs and ECG Parameters

Mean values and mean changes from baseline for ECG parameters in the pooled population are provided in Table 8 by treatment group. Mean changes from baseline in ECG (mean change from baseline <1 ms, with two standard deviations <50 ms, with the mean baseline 415 ms) and vital sign parameters were generally small and were not considered to be clinically relevant. The incidences of TEAEs related to ECG and vital sign abnormalities were generally low and were similar in the prucalopride ≤2 mg/day and placebo groups as well as in men and women. The proportion of patients who experienced any adverse cardiovascular events was low and comparable between groups (1.8 % for placebo vs 2.0 % for prucalopride). None of the individual TEAEs were reported for >1 % of patients in either sex in either treatment group. One patient (<1 %) in the placebo group, and no patients in the prucalopride group, experienced angina pectoris; one patient in each of the placebo and prucalopride groups (<1 % for both) experienced myocardial ischemia.

Table 8.

ECG results in the pooled patient population

| Parameter | Placebo, N = 1279 | Prucalopride ≤2 mg/day, N = 1273 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) change from baseline | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) change from baseline | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | ||||

| Baseline | 66.4 (10.48) | 66.9 (10.37) | ||

| Week 12 | 68.2 (11.11) | 1.5 (9.60) | 68.6 (10.30) | 1.8 (9.21) |

| PR interval (ms) | ||||

| Baseline | 158.3 (26.11) | 157.9 (25.69) | ||

| Week 12 | 156.7 (24.01) | –0.9 (16.46) | 154.1 (22.61) | –3.2 (16.13) |

| QRS interval (ms) | ||||

| Baseline | 88.4 (13.94) | 88.5 (14.29) | ||

| Week 12 | 86.7 (13.69) | –0.4 (9.71) | 87.9 (13.79) | 0.2 (8.88) |

| QT interval (ms) | ||||

| Baseline | 396.6 (33.79) | 393.9 (34.01) | ||

| Week 12 | 391.4 (33.51) | –4.1 (26.64) | 389.8 (31.52) | –4.1 (26.85) |

| QTcB (ms) | ||||

| Baseline | 414.3 (27.60) | 413.7 (30.11) | ||

| Week 12 | 414.1 (27.23) | 0.3 (24.36) | 414.5 (26.89) | 1.2 (24.76) |

| QTcF (ms) | ||||

| Baseline | 408.0 (23.90) | 406.7 (27.93) | ||

| Week 12 | 406.1 (25.38) | –1.2 (21.33) | 405.9 (24.83) | –0.6 (22.16) |

bpm beats/min, ECG electrocardiogram, QTcB QT interval corrected according to Bazett’s formula, QTcF QT interval corrected according to Fridericia’s formula, SD standard deviation

Discussion

The findings of this integrated analysis of six double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 and 4 trials confirm that prucalopride is an effective treatment for adults with CC. Over the 12-week treatment period, significantly more patients in the prucalopride group than in the placebo group achieved a mean of ≥3 SCBMs/week. These results are consistent with the treatment response observed in the individual trials [18–21], with the exception of the SPD555-401 trial, which failed to demonstrate a statistically significant effect of prucalopride on this primary endpoint after both 12 and 24 weeks of treatment. An extensive evaluation of the SPD555-401 trial has been unable to provide an explanation for the reported lack of efficacy [22, 23].

Overall results in the current study were similar for men and women, although there was a difference in the response rate over time between the sexes. This could be related to differences in demographics (other than gender) and disease characteristics at baseline, or to intrinsic differences in responsiveness to prucalopride between men and women. Furthermore, prucalopride was significantly more efficacious than placebo as assessed by a variety of secondary endpoints, including improvements in PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL scores and rescue medication use. An exploratory efficacy analysis indicated that even patients with very severe CC—those with no SBMs at baseline—benefited from prucalopride treatment.

The findings of this integrated analysis confirm and extend (with the addition of three trials [21–23]) the results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, which demonstrated the efficacy of a number of highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonists, including prucalopride, in the treatment of patients with CC [25]. Efficacy was evaluated on the basis of several important clinical outcomes (BM frequency, stool consistency, constipation-related quality of life, and symptom scores) [25]. The results of this analysis were also similar to those of two separate integrated analyses involving only women [26, 27]. The present integrated analysis differed from the previous analyses with regard to the inclusion of the male patient population from the SPD555-302 study, allowing meaningful comparison to be made of the response of men and women to prucalopride treatment [25–27]. Prucalopride showed a consistent treatment effect in both sexes.

Several novel therapeutic options are available for treatment of men and women with CC. These typically target two physiological processes: motility and secretion. Gastrointestinal motility is regulated in part by high-amplitude propagating contractions (HAPCs), which occur, on average, six times per day in healthy individuals—particularly immediately after awakening and after meals [28, 29]. HAPCs result in mass movement of colonic contents, and are often followed by an urge to defecate [28]. In patients with CC, the frequency and duration of HAPCs are reduced in comparison with healthy individuals [30]. Prucalopride has been shown to stimulate gastrointestinal motility, including accelerating gastric, proximal colonic, and colonic transit [31]. Therefore, prucalopride may be particularly beneficial for patients with CC who have a paucity of HAPCs, or in those who do not respond to other medications. Secretagogues, such as lubiprostone or linaclotide, exert their effects by increasing intestinal and colonic secretion of chloride-rich fluid into the intestinal lumen [32]; there is no reported evidence that these agents induce HAPCs; this was specifically tested with lubiprostone in comparison with placebo during fasting and postprandially in healthy human volunteers [33].

In the current integrated analyses, the NNT with prucalopride to achieve the primary efficacy endpoint in one patient was 8.8 (95 % CI 7.1–11.6). In a meta-analysis of data from three trials of linaclotide in patients with CC, the NNT for the primary endpoint of these trials (>3 SCBMs/week and an increase of ≥1 SCBM/week, for 75 % of weeks) was 7 (95 % CI 5–8) [34].

Other selective 5-HT4 receptor agonists have been evaluated for the treatment of patients with CC: velusetrag, naronapride, and YKP10811 [35–38]. However, trials of these agents have, to date, been relatively small phase 2 studies or pharmacodynamic studies in healthy volunteers; the current integrated analysis provides the most robust evidence that this class of medication, and particularly prucalopride, is efficacious in the treatment of patients with CC.

There has been considerable interest in the safety profile of 5-HT4 receptor agonists in development, owing to the apparent association of the non-selective 5-HT4 receptor agonists tegaserod and cisapride with cardiovascular adverse events [39, 40]. The results of this integrated analysis show that prucalopride has a favorable safety and tolerability profile. This is consistent with the findings of two previous studies that focused on assessment of the safety of prucalopride [41, 42]. Of particular interest, no cardiovascular safety signals were identified; specifically, the mean QT interval corrected according to Bazett’s formula (QTcB) and the mean QT interval corrected according to Fridericia’s formula (QTcF) were both <470 ms.

A potential limitation of this integrated analysis is that the results of one of the six trials deviated from those of the other trials for reasons that are not clear, causing moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 56 %). However, the results of the other five trials, involving 86 % of patients, were highly homogeneous (I2 = 6.8 %). Furthermore, homogeneity was demonstrated across trials conducted in Asian, American, and European populations, confirming the validity of the results of the integrated analysis.

In conclusion, in this integrated analysis of over 2000 patients from four continents, prucalopride was demonstrated to be efficacious in the treatment of individuals with CC. Prucalopride was also shown to have a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with no cardiovascular adverse event concerns. Efficacy and safety findings were consistent in both men and women.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance for the manuscript was provided by Vivienne Stein-Rostaing, PhD, and Libby Beake, MBBS, of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, with funding from Shire.

Funding

This study was funded by Shire-Movetis NV, Turnhout, Belgium.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- BM

Bowel movement

- CBM

Complete bowel movement

- CC

Chronic constipation

- CI

Confidence interval

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- FoTA

Final on-treatment assessment

- HAPC

High-amplitude propagating contraction

- 5-HT4

5-Hydroxytryptamine 4

- NNT

Number needed to treat

- PAC-QOL

Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire

- PAC-SYM

Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms questionnaire

- QTcB

QT interval corrected according to Bazett’s formula

- QTcF

QT interval corrected according to Fridericia’s formula

- SAS

Statistical Analysis System

- SBM

Spontaneous bowel movement

- SCBM

Spontaneous complete bowel movement

- SD

Standard deviation

- TEAE

Treatment-emergent adverse event

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Michael Camilleri has received research support from Shire and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals and has participated in an advisory group with Ironwood (gastroparesis, compensation to Mayo Clinic). Hubert Piessevaux has received speaker and consulting fees from Shire. Yan Yiannakou has received speaker fees and an educational grant from Shire-Movetis. Jan Tack has provided scientific advice to Almirall, AstraZeneca, Danone, GI Dynamics, GlaxoSmithKline, Ironwood, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Rhythm, Shire, Takeda, Theravance, Tsumura, Will-Pharma, and Zeria; has received research grants or support from Abbott, Novartis, and Shire; and has served on speakers’ bureaus for Abbott, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Shire, Takeda, and Zeria. René Kerstens is a consultant to Shire and was an employee of Shire at the time of the study. Eamonn M. M. Quigley has provided scientific advice to Alimentary Health, Almirall, Forest, Ironwood, Movetis, Rhythm, Salix, Shire, and Vibrant; has received honoraria for speaking from Almirall, Ironwood, Metagenics, Procter & Gamble, and Shire-Movetis; and has received research support from Rhythm and Vibrant. MeiYun Ke has received speaker fees from Janssen. Susana Da Silva is a shareholder and employee of Shire. Amy Levine is a shareholder and former employee of Shire.

Contributor Information

Michael Camilleri, Email: camilleri.michael@mayo.edu.

Hubert Piessevaux, Email: hubert.piessevaux@uclouvain.be.

Yan Yiannakou, Email: yan.yiannakou@cddft.nhs.uk.

Jan Tack, Email: jan.tack@med.kuleuven.be.

René Kerstens, Email: rkerstens@orionstatistics.nl.

Eamonn M. M. Quigley, Email: equigley@tmhs.org

MeiYun Ke, Email: kemypumch2006@aliyun.com.

Susana Da Silva, Email: sdasilva@shire.com.

Amy Levine, Email: ablevinemd@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:938–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassotti G, Villanacci V. Slow transit constipation: a functional disorder becomes an enteric neuropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4609–4613. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnamurthy S, Schuffler MD, Rohrmann CA, Pope CE., II Severe idiopathic constipation is associated with a distinctive abnormality of the colonic myenteric plexus. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(85)80128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Heady S, Coss-Adame E, Rao SS. Clinical utility of colonic manometry in slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:487–495. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinning PG, Wiklendt L, Maslen L, et al. Colonic motor abnormalities in slow transit constipation defined by high resolution, fibre-optic manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:379–388. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wattchow D, Brookes S, Murphy E, et al. Regional variation in the neurochemical coding of the myenteric plexus of the human colon and changes in patients with slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:1298–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He CL, Burgart L, Wang L, et al. Decreased interstitial cell of Cajal volume in patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:14–21. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DA. Treating chronic constipation: how should we interpret the recommendations? Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:547–557. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200626100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinning PG, Hunt L, Patton V, et al. Treatment efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation in slow transit constipation: a two-phase, double-blind randomized controlled crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:733–740. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corsetti M, Tack J. New pharmacological treatment options for chronic constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:927–941. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.900543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonini M. 5-Hydroxytryptamine effects in the gut: the 3, 4, and 7 receptors. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Maeyer JH, Lefebvre RA, Schuurkes JA. 5-HT4 receptor agonists: similar but not the same. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:99–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tack J, Camilleri M, Chang L, et al. Systematic review: cardiovascular safety profile of 5-HT(4) agonists developed for gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:745–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman H, Pasternack M. The action of the novel gastrointestinal prokinetic prucalopride on the HERG K+ channel and the common T897 polymorph. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;554:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Medicines Agency. Annex I. Summary of product characteristics Resolor. 2014.

- 18.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–2354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut. 2009;58:357–365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.162404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation—a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, et al. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:999-e541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piessevaux H, Corazziari E, Rey E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-term treatment with prucalopride. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:805–815. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yiannakou Y, Piessevaux H, Bouchoucha M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of prucalopride in men with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin A, Camilleri M, Kolar G, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: highly selective 5-HT4 agonists (prucalopride, velusetrag or naronapride) in chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:239–253. doi: 10.1111/apt.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tack J, Quigley E, Camilleri M, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R. Efficacy and safety of oral prucalopride in women with chronic constipation in whom laxatives have failed: an integrated analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:48–59. doi: 10.1177/2050640612474651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke M, Tack J, Quigley EM, et al. Effect of prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in Asian and non-Asian women: a pooled analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:458–468. doi: 10.5056/jnm14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bharucha AE. High amplitude propagated contractions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:977–982. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassotti G, Gaburri M, Imbimbo BP, et al. Colonic mass movements in idiopathic chronic constipation. Gut. 1988;29:1173–1179. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinning PG, Di Lorenzo C. Colonic dysmotility in constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, et al. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:354–360. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camilleri M. New treatment options for chronic constipation: mechanisms, efficacy and safety. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:29B–35B. doi: 10.1155/2011/670484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweetser S, Busciglio IA, Camilleri M, et al. Effect of a chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, on colonic sensory and motor functions in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G295–G301. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90558.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Videlock EJ, Cheng V, Cremonini F. Effects of linaclotide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic constipation: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1084–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manini ML, Camilleri M, Goldberg M, et al. Effects of Velusetrag (TD-5108) on gastrointestinal transit and bowel function in health and pharmacokinetics in health and constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldberg M, Li YP, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy and tolerability of velusetrag, a selective 5-HT4 agonist with high intrinsic activity, in chronic idiopathic constipation—a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose–response study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1102–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camilleri M, Vazquez-Roque MI, Burton D, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of a novel prokinetic 5-HT receptor agonist, ATI-7505, in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:30–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin A, Acosta A, Camilleri M, et al. A randomized trial of 5-hydroxytryptamine-receptor agonist, YKP10811, on colonic transit and bowel function in functional constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;13:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quigley EM. Cisapride: what can we learn from the rise and fall of a prokinetic? J Dig Dis. 2011;12:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan KY, de Vries R, Leijten FP, et al. Functional characterization of contractions to tegaserod in human isolated proximal and distal coronary arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;619:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendzelevski B, Ausma J, Chanter DO, et al. Assessment of the cardiac safety of prucalopride in healthy volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and positive-controlled thorough QT study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1256-e117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]