ABSTRACT

Proteus mirabilis contributes to a significant number of catheter-associated urinary tract infections, where coordinated regulation of adherence and motility is critical for ascending disease progression. Previously, the mannose-resistant Proteus-like (MR/P) fimbria-associated transcriptional regulator MrpJ has been shown to both repress motility and directly induce the transcription of its own operon; in addition, it affects the expression of a wide range of cellular processes. Interestingly, 14 additional mrpJ paralogs are included in the P. mirabilis genome. Looking at a selection of MrpJ paralogs, we discovered that these proteins, which consistently repress motility, also have nonidentical functions that include cross-regulation of fimbrial operons. A subset of paralogs, including AtfJ (encoded by the ambient temperature fimbrial operon), Fim8J, and MrpJ, are capable of autoinduction. We identified an element of the atf promoter extending from 487 to 655 nucleotides upstream of the transcriptional start site that is responsive to AtfJ, and we found that AtfJ directly binds this fragment. Mutational analysis of AtfJ revealed that its two identified functions, autoregulation and motility repression, are not invariably linked. Residues within the DNA-binding helix-turn-helix domain are required for motility repression but not necessarily autoregulation. Likewise, the C-terminal domain is dispensable for motility repression but is essential for autoregulation. Supported by a three-dimensional (3D) structural model, we hypothesize that the C-terminal domain confers unique regulatory capacities on the AtfJ family of regulators.

IMPORTANCE Balancing adherence with motility is essential for uropathogens to successfully establish a foothold in their host. Proteus mirabilis uses a fimbria-associated transcriptional regulator to switch between these antagonistic processes by increasing fimbrial adherence while simultaneously downregulating flagella. The discovery of multiple related proteins, many of which also function as motility repressors, encoded in the P. mirabilis genome has raised considerable interest as to their functionality and potential redundancy in this organism. This study provides an important advance in this field by elucidating the nonidentical effects of these paralogs on a molecular level. Our mechanistic studies of one member of this group, AtfJ, shed light on how these differing functions may be conferred despite the limited sequence variety exhibited by the paralogous proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Transcriptional regulation in response to environmental cues, including temperature and nutrient availability, is critical to allow bacteria to adapt to their surroundings. The advent of whole-genome sequencing has led to the discovery that some pathogenic bacteria devote as much as 10% of their genome to regulatory systems, such as transcription factors, allowing for the appropriate protective or adaptive response to new environments (1, 2).

Urinary tract pathogens, such as the Gram-negative enterobacterium Proteus mirabilis, have long been known to tightly regulate the production of antigenic supramolecular structures, such as fimbriae and flagella, conceivably to avoid detection by the host's immune system (3). P. mirabilis has been well characterized for its ability to change from short vegetative rod-shaped swimmer cells into elongated hyperflagellated swarm cells that are capable of multicellular movement across surfaces (4, 5). A relatively minor cause of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in healthy individuals, this organism commonly causes cystitis and pyelonephritis in patients with indwelling catheters or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract (6). UTIs occur almost exclusively in an ascending route of infection; bacteria of fecal origin gain access to the bladder and subsequently ascend to the kidneys via the ureters, from where they can gain access to the bloodstream, causing potentially fatal septic infections (7). Previous studies have demonstrated that the naturally opposing forces of both flagellum-mediated motility and adhesion by fimbriae contribute to successful disease progression (8).

The P. mirabilis genome contains a total of 17 potential chaperone-usher fimbrial operons (9), most of which encode associated transcriptional regulators (10). Four of these 17 operons have individually been linked to virulence in a murine model of infection (11–16). Mannose-resistant Proteus-like (MR/P) fimbriae, the major adhesin produced during infection, contribute to bladder colonization (16). Transcribed at low levels in culture, the genes of this phase-variable operon show the largest fold induction in vivo (17). In contrast, ambient-temperature fimbriae (ATF) are most highly expressed when bacteria are cultured statically at 23°C (18). Expectedly, deletion of atf does not attenuate P. mirabilis in murine challenges (19). However, Jansen and colleagues observed that the major fimbrial subunit AtfA was upregulated in bladder tissue in an mrp mutant, suggesting a possible infectious role for these fimbriae (20).

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica strains also contain multiple fimbrial operons, and in these species, fimbrial regulation is hierarchical (21, 22), resulting in the predominant expression of one fimbria under a given condition. In contrast, little is currently known of potential cross talk between the many different fimbriae of P. mirabilis.

MrpJ, a helix-turn-helix (HTH) xenobiotic response element (XRE) family transcriptional regulator encoded by the last gene of the mrp operon, serves as a switch between motility and adhesion (23). This fimbria-associated transcription factor directly binds the promoters of the flagellar master regulator flhDC and its own operon, thereby repressing motility while simultaneously upregulating the production of MR/P fimbriae (10, 24). Recent microarray studies utilizing a strain that mimics levels of MrpJ observed during UTIs further illustrated that MrpJ has many nonmotility targets and implicated this protein as a master regulator of virulence (24). A previous report studying the functions of 14 additional P. mirabilis mrpJ paralogs found that the majority repressed both swimming and swarming motility when provided individually in trans, like MrpJ. Notably, the swarm phenotypes varied considerably between strains, as did flagellin protein levels, suggesting that the different paralogs exerted nonidentical effects on their gene targets (10). The majority of MrpJ paralogs are associated with other fimbrial operons. This includes AtfJ, an MrpJ paralog encoded by the atf operon (10). Major questions remain about the purposes of these fimbria-associated transcriptional regulators.

In this study, we demonstrate that several fimbria-associated transcription factors regulate their own operons, and they influence the transcription of other fimbriae. Our genetic and biochemical data establish that AtfJ directly binds a site within the atfA promoter, and this region is required for AtfJ-mediated expression of the atf operon. Utilizing chimeric proteins fusing AtfJ and two other MrpJ paralogs, we determined that the C-terminal domain of AtfJ is necessary but not sufficient for autoregulation, while residues in the DNA-binding HTH domain contribute to both motility repression and autoregulation. Furthermore, we determined the arginine residue at position 83 in the C-terminal domain to be critical for the ability of AtfJ to activate expression of its own promoter independently of its ability to bind DNA. Altogether, this study highlights several unique attributes of AtfJ function and provides the first insight into the existence of a fimbrial regulatory network in P. mirabilis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in low-salt nonswarming LB broth (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.5 g NaCl, per liter) or on LB medium solidified with 1.5% agar, unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations when required: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 15 μg/ml gentamicin, and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The P. mirabilis HI4320 wild-type and Φ(atfAp-lacZ) fusion strains transformed with pLX3607 or its derivative plasmids were initially selected on LB agar with 25 to 50 μg/ml ampicillin but subsequently maintained on 100 μg/ml.

Plasmid construction.

Primer sequences are described in Table S2 in the supplemental material. All PCR-generated plasmid inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The C-terminal His6 epitope tag-containing plasmids pNB001, pNB010, and pNB012 were constructed by amplifying ucaJ, mrpJ, and atfJ, respectively, from P. mirabilis HI4320 genomic DNA using a downstream primer that incorporated a region encoding His6 and by cloning the NcoI-HindIII fragments into pLX3607.

Chimeric fusion proteins containing sequence elements from two of the three MrpJ paralogs used in this study (MrpJ, UcaJ, and AtfJ) were made by (i) splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) (25) or (ii) using a reverse primer that annealed at the fusion point and encoded the desired amino acids in its sequence. Plasmids pMP125, pMP129, and pLX3805 served as the templates. The insert encoding a truncated AtfJ with residues 1 to 70 [AtfJ(1–70)] was amplified using a His6-containing primer annealing to the end of the predicted helix-turn-helix motif. All described site-directed AtfJ mutations were constructed by SOE-PCR and desired fragments amplified from pMP129 or pNB012. Whenever SOE-PCR was employed, fragments were joined with the same primers used to generate mrpJ-His6, ucaJ-His6, and atfJ-His6 and ligated into pLX3607 following digestion with NcoI/HindIII.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

RNA isolation and analysis were performed exactly as described previously (26). To measure the expression of genes of interest in strains overproducing individual MrpJ paralogs, stationary-phase overnight cultures were subcultured to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.04 in 3 ml LB supplemented with ampicillin and grown at 37°C with aeration until they reached mid-logarithmic growth phase (OD600, 0.7 to 0.9). Cells were immediately transferred into the appropriate volume of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) for stabilization of RNA prior to isolation.

Determination of the transcriptional start site.

5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Life Technologies). Four identical full-length clones were sequenced to determine the transcriptional start site of the atf operon.

Construction of transcriptional fusions to lacZ.

5′-end-truncated promoter fragments of atfA were PCR amplified from either P. mirabilis HI4320 genomic DNA or the pNB025 template using a common reverse primer (NB56) and forward primers that anneal at desired locations upstream. The resulting XhoI-NotI fragments were cloned into pNB022. All cloned inserts were sequenced using primers NB52 and NB60. Operon fusions were integrated at the HI4320 attTn7 locus downstream of glmS in single copy, as previously described (24). Successful integration events were confirmed by PCR.

β-Galactosidase assay.

Bacterial overnight cultures were diluted to a starting OD600 of 0.04 in 5 ml of LB with ampicillin. Subcultures were grown with aeration until mid-logarithmic phase (OD600, 0.7 to 0.9) or for 3 h, followed by a 1-h induction with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), as indicated in the respective figure legends. Cells were placed on ice, harvested by centrifugation, and washed in 0.88% NaCl. Pellets were used directly in enzymatic assays or after overnight storage at −20°C.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined at room temperature, exactly as described previously (24). Activities are expressed in arbitrary Miller units (27) or as percentages of activity after all values were normalized to that measured for the atfAp-lacZ operon fusion strain containing nucleotides −655 to +220 (where +1 is the transcription start site of atfA), herein called Φ(−655 to +220), when atfJ (pMP129) was expressed in trans. Individual cultures were assayed in duplicate, and the graphed values present the averages of the results from three biologically independent experiments plus standard deviations (SD) (represented by error bars).

Swarm motility assay.

Overnight cultures were subcultured to an initial OD600 of 0.04. Bacteria were grown at 37°C with aeration until they reached mid- to late logarithmic phase (OD600, 0.9 to 1.5), at which time cultures were placed on ice and adjusted to an OD600 of 1. Subsequently, 5 μl was spotted on the center of a swarm agar plate (per liter, 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g NaCl, and 1.5 g agar) supplemented with ampicillin. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 17 h before swarm radii were determined. Results presented are the means for three biological replicates.

Immunoblot analysis.

Bacterial cultures were grown as specified in the figure legends. At the appropriate time points, 1 OD600 equivalent of cells was pelleted at top speed in a microcentrifuge. Bacteria were resuspended in either 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole; pH 8) supplemented with SDS sample buffer at a final concentration of 1× or 100 μl of 1× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 8 min prior to analysis. Proteins were separated on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels and transferred to nitrocellulose (0.45 μm; Bio-Rad). Anti-His5 (Qiagen) was used at a dilution of 1:1,000, and anti-FlaA (28) was used at a dilution of 1:20,000. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Pierce/Thermo Fisher) were used at a dilution of 1:20,000 for chemiluminescent detection with the ECL 2 substrate (Thermo Scientific). All exposures are representative of the results from three independent biological experiments.

Antibodies to FlaA were a kind gift from Harry Mobley.

MrpJ paralog secondary-structure prediction.

The secondary structures of AtfJ, MrpJ, and UcaJ were predicted using PSIpred version 3.3 (29).

Recombinant protein purification.

We produced His6-tagged AtfJ and AtfJ with the R83A mutation [AtfJ(R83A)] in E. coli and purified proteins under native conditions, according to the guidelines published in the QIAexpressionist manual (Qiagen). Briefly, 2,000 ml of BL21(pLys)DE3 cells transformed with overexpression plasmids was grown to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 at 37°C and 225 rpm, at which time they were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and incubated at 30°C with shaking for 5 to 6.5 h. Cells were pelleted and stored at −20°C prior to lysis. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8), lysed by sonication, and subjected to affinity purification using 500 μl of packed, equilibrated nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen) for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed extensively following the incubation period in wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8). Proteins were eluted in 500-μl fractions (elution buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8]), and individual fractions were assessed for protein content and purity by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Purified proteins were buffer exchanged into 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol using Econo-Pac 10DG desalting prepacked gravity flow columns (Bio-Rad), and aliquots were stored at −80°C. The Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to determine the concentration of all protein preparations.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

Gel shifts were performed using the second-generation digoxigenin (DIG) gel shift kit (Roche) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, PCR-amplified DNA probes (promoter fragments of atfA, 169 bp each) were incubated with various amounts of the desired protein (wild-type AtfJ-His6 or the R83A mutant) for 15 min at room temperature prior to separation on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel. Poly[d(I-C)] was included in all reaction mixtures as nonspecific competitor DNA.

Modeling of the AtfJ structure.

The amino acid sequence of AtfJ was threaded onto a dimeric crystal structure of P22 c2 repressor-DNA complex (PDB accession number 2R1J) using the Internal Coordinate Mechanics (ICM) software package, and all side chains were energy minimized by a Monte Carlo procedure (30). The ICM optimal docking area (ODA) function was used to identify regions of potential protein-protein interactions of AtfJ. The algorithm identifies surface patches with optimal docking desolvation energy based on atomic solvation parameters adjusted for protein-protein interactions (31). It has been benchmarked on a panel of nonhomologous proteins involved in nonobligate protein-protein interactions. The structural figures were rendered with ICM or the PyMOL molecular graphics system (Schrödinger, LLC).

Statistical analysis.

The significance of qRT-PCR data, swarm motility repression, and β-galactosidase activity was calculated using Student's t test. Graphing and analysis were performed using Prism software (version 6.0g; GraphPad).

RESULTS

MrpJ paralogs exhibit variations in autoregulatory and cross-regulatory capacities.

We recently reported the transcriptomic microarray analysis of a strain expressing MrpJ in trans at levels mimicking those observed in vivo. Production of MrpJ in this physiologically relevant amount resulted in altered expression of several fimbrial genes (pmfA, fim8A, and fim14A), besides positively affecting the transcription of its own mrp operon (24). To expand our limited knowledge of the interplay and regulation of the 17 potential P. mirabilis fimbrial operons, we tested whether select MrpJ paralogs could (i) autoregulate their operons and (ii) cross-regulate other fimbrial operons or fimbria-related genes. We hypothesize that fimbriae and their associated transcriptional regulators are produced in a range of specific environments and fulfill complementary, but nonidentical, roles. To examine these questions, we focused on a subset of four fimbriae and associated regulators of particular interest. First, both MR/P and uroepithelial cell adhesin (UCA) have individually been shown to play a role in infection using mouse models of ascending UTI (15, 16). Next, Fim8 was found to contribute to virulence in a signature-tagged mutagenesis screen (14), but this has not independently been verified. Finally, ATF is not currently thought to contribute to P. mirabilis infection (19), because it is optimally produced at 23°C (18), while expression of virulence genes tends to be induced upon the shift from low environmental to higher host temperatures of 37°C (32).

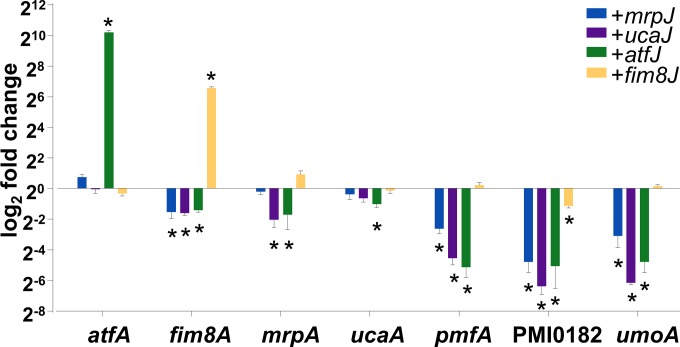

We first assessed whether the selected MrpJ paralogs showed an autoregulatory phenotype similar to that of MrpJ (24). To do so, we utilized a set of strains expressing individual MrpJ paralogs from the same IPTG-inducible vector used in our microarray studies (9). Both AtfJ and Fim8J induced expression of the major fimbrial subunits of their own operons and at a much greater magnitude than what was reported for MrpJ (Fig. 1) (24). The relatively minor fold change previously documented for mrpA in the presence of MrpJ was not observed in this set of experiments, possibly due to small variations in the growth conditions. Interestingly, overproduction of UcaJ did not affect the transcription of ucaA.

FIG 1.

Fimbrial regulation by selected MrpJ paralogs. Overexpression of individual mrpJ paralogs affects transcription of fimbrial target genes during mid-logarithmic phase compared to that of the vector-only control. Strains expressing mrpJ paralogs in trans (mrpJ, ucaJ, atfJ, or fim8J) are indicated by the key, and genes measured by qRT-PCR are indicated on the x axis. The data are the results from three independent experiments, normalized to results with rpoA. Genes were considered to be differentially regulated if transcription was at least 2-fold up- or downregulated and statistically significant compared with results for the empty-vector control. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). *, statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05).

Additionally, we determined each paralog's cross-regulatory activity on select fimbrial genes using the same approach. We found that most interfimbrial effects were repressive, with the most-pronounced effects on pmfA, the gene encoding the major fimbrial subunit of Proteus mirabilis fimbriae (PMF), and the orphan regulator PMI0182 (10). Notably, the pmf fimbrial operon does not encode an MrpJ paralog. None of the tested paralogs repressed atfA, and the strongest effect on ucaA was a 2-fold repression by AtfJ.

Most members of the MrpJ family have been shown to repress swarming (10), and as expected, the majority of MrpJ paralogs tested repressed the positive swarm regulator umoA (33). While fim8J overexpression did not alter the expression profile of umoA, this result is consistent with the minor repression of swarm motility in the absence of IPTG reported previously (10). In general, despite Fim8J's pronounced effects on the transcription of fim8A, the effects of Fim8J overproduction were relatively minor and, with the exception of PMI0182 repression, did not reach statistical significance.

Together, these results support the notion that MrpJ paralogs regulate overlapping pathways while fulfilling nonidentical roles, warranting their conservation across different P. mirabilis isolates.

Identification of an AtfJ-responsive element in the atfA promoter.

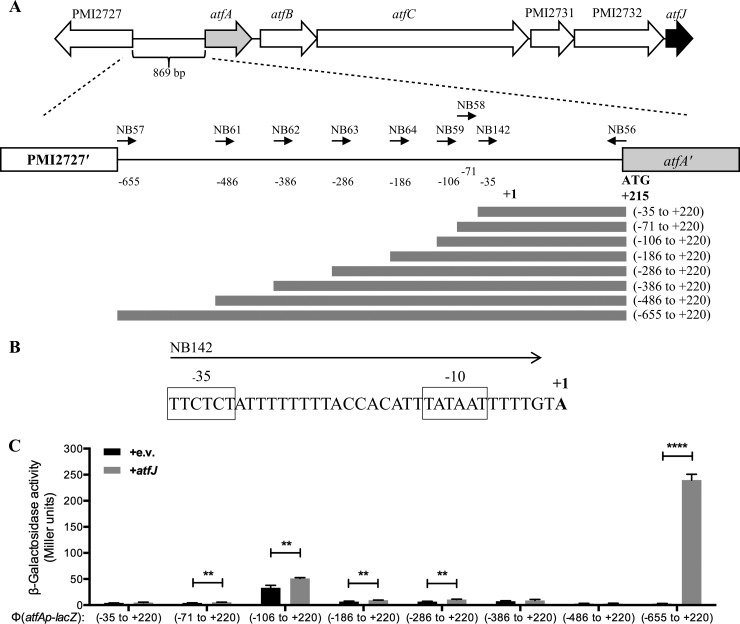

To broaden our understanding on how these paralogs manifest their differential functions, we focused on the paralog that induced the largest autoregulatory response, AtfJ. First, we sought to determine the promoter element required for atfJ-dependent induction of atfA. Using 5′-RACE, we mapped the transcriptional start of atfA to an adenine residue located 214 nucleotides upstream of the predicted translational start (+1) (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Visual inspection of the immediate upstream DNA sequence revealed the presence of perfect −10 (TATAAT) and divergent −35 (TTCTCT) σ70 recognition sites (34), separated by an optimal 17-bp spacer (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

AtfJ-dependent activation of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) expression. (A) Schematic showing the atf gene locus, including the divergently expressed upstream open reading frame PMI2727. Depicted numbers are the positions of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusions relative to the transcriptional start site of atfA (+1), which was determined by 5′-RACE. Bars represent Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusions with respect to the included promoter elements. (B) Nucleotide sequence surrounding the transcriptional start site of atfA. The transcriptional start site (+1) is indicated by bold type. Putative −10 and −35 regions are indicated. (C) Effect of promoter deletion on atfJ-dependent activation of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) in mid-logarithmic growth phase. Single-copy fusions to lacZ include the specified amounts of DNA upstream of the predicted AtfA start codon. Strains were transformed with the empty vector (pLX3607 [+e.v.]) or atfJ expression plasmid (pMP129). β-Galactosidase activity was determined as outlined in Materials and Methods; error bars represent the SD. Statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: **, P is ≤0.01, and ****, P is ≤0.0001.

To identify the promoter region required for autoinduction of the atf operon, we fused promoter fragments of various lengths to a lacZ reporter and measured β-galactosidase activity while replicating the culture conditions of the expression analysis (Fig. 1). The Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusions were integrated in single copy at the attTn7 locus, downstream of glmS, as described previously (24). The promoter fusions covered a wide range of sequences, with the shortest fragment including only the identified −10 and −35 binding sites, while the longest fragment contained the whole intergenic region between atfA and the divergently expressed upstream gene PMI2727. To include all relevant regulatory elements, a common reverse primer annealing to the start of the atfA coding region was used to amplify all fragments of interest (Fig. 2A).

The shortest promoter fragment tested (nucleotides −35 to +220) showed almost no activity, irrespective of the expression of atfJ. This construct contains the predicted −35 and −10 regions, but we hypothesize that divergence from the consensus sequence results in transcriptional activity below the detection limit. Similarly, the majority of the other promoter fragments analyzed were poorly transcribed, regardless of atfJ expression. Interestingly, the fragment ranging from nucleotides −106 to +220 showed a small but consistent increase in activity, largely independent of AtfJ production, an effect that is not seen with the two neighboring fragments (from nucleotides −71 to +220 and from nucleotides −186 to +220).

Most importantly, the transcriptional fusion comprising the whole intergenic region of atfA and PMI2727 showed almost a 100-fold induction upon expression of atfJ in trans, which matched the marked upregulation that we observed by qRT-PCR. Our results suggest that this distal region between 655 and 486 bp upstream of the atfA transcriptional start is required for induction of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) expression by AtfJ, and we designed a series of experiments to further probe this interaction.

Validation of epitope tagging of several MrpJ paralogs.

Although overproduction of AtfJ dramatically induced expression of the atf operon, other MrpJ paralogs did not affect atfA transcription (Fig. 1). To dissect which domains of AtfJ were critical to the autoregulation of atf, we constructed a series of site-directed AtfJ mutants, as well as chimeric fusions, and tested how they affected transcription using the approach described above. We chose MrpJ and UcaJ for the chimeric protein approach; while MrpJ has already been established as a master regulator of virulence (24), UcaJ overproduction consistently showed a larger effect on the examined fimbrial targets, despite lacking the ability to induce its own operon. Additionally, deletion of ucaA, which likely has polar effects on ucaJ expression, attenuated P. mirabilis in a mouse model of ascending UTI (15). To assess the production of all variants, we monitored their protein levels using an epitope tag. Wild-type AtfJ, MrpJ, and UcaJ were produced with C-terminal His6 tags from the IPTG-inducible vector pLX3607. Immunoblot analysis of HI4320 whole-cell lysates producing individual epitope-tagged paralogs using a monoclonal His5 antibody revealed approximately equal levels of MrpJ-His6, AtfJ-His6, and UcaJ-His6 (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

To assess whether the epitope-tagged variants retained their functionality, we employed two approaches: (i) monitoring of the levels of the major flagellin FlaA and (ii) measurement of swarm motility repression (10). As expected, production of the epitope-tagged variants led to a marked decrease in detectable FlaA (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) compared to that of the vector control, suggesting that epitope tagging does not interfere with the functionality of these transcriptional regulators. Additionally, the His6-tagged variants retained the overall ability to repress swarming, and the observed swarm phenotypes diverged from the characteristic bull's-eye pattern exhibited by the empty-vector control. However, compared to the untagged wild-type versions, all three tagged paralogs displayed a radial swarm pattern (see Fig. S2B, top) of a significantly larger diameter than that of the untagged paralogs (see Fig. S2B, bottom, and C). Altogether, we concluded that epitope tagging only minimally reduced paralog functionality, and we employed these variants in our studies.

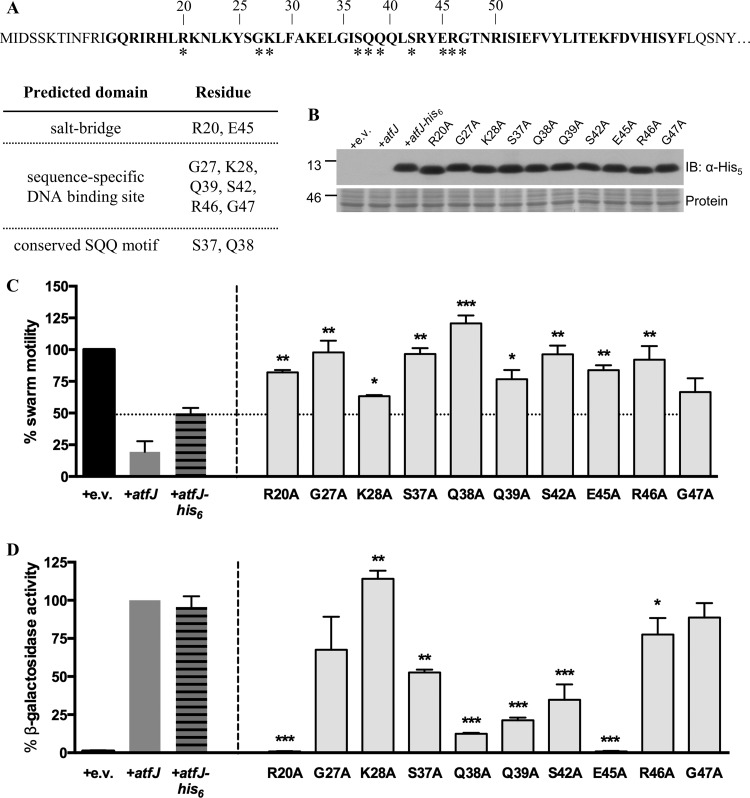

The predicted HTH motif of AtfJ is critical for swarm repression.

Having identified a promoter element critical for AtfJ-dependent activation of atfA expression, we aimed to define the parts of AtfJ required for its function. A previously published ClustalW alignment of the amino acid sequences of all 15 MrpJ paralogs (10) shows that any sequence homology is limited to the predicted HTH motif located at the center of the protein. Published data on MrpJ demonstrated that residues within the predicted HTH motif are essential for swarm motility repression (10). BLAST analysis of AtfJ indicated six amino acids (G27, K28, Q39, S42, R46, and G47) as potential sequence-specific DNA-binding sites within the conserved HTH domain, while residues R20 and E45 were predicted to form a salt bridge to stabilize the structure of the HTH. To assess the contribution of these residues to AtfJ function, each of these amino acids was replaced with alanine using site-directed mutagenesis of AtfJ-His6. In addition to mutating all the aforementioned amino acids, we mutated residues S37 and Q38, which mark the beginning of the previously identified “conserved core” common to all MrpJ paralogs (10) (Fig. 3A), and we confirmed that all mutants were produced at approximately equal levels (Fig. 3B). We then assessed the ability of these mutants to repress swarm motility (Fig. 3C). With the exception of AtfJ G47A, the capacity of all mutants to repress motility was significantly decreased compared to that of the wild-type AtfJ-His6 control (Fig. 3C). In particular, the G27A, S37A, Q38A, S42A, and R46A mutants showed a near-complete loss of motility repression, as indicated by an average swarm motility of >90% of the empty vector. Incidentally, the K28A mutant also retained the ability to repress swarming; although its difference from the parental control was statistically significant, it is likely biologically functional.

FIG 3.

Role of the HTH motif in swarm repression and autoregulation. (A) Predicted AtfJ protein sequence. The HTH motif is indicated in bold type; features associated with replaced amino acids are summarized in the table below. Asterisks indicate the locations of alanine substitution mutations. (B) Anti-His5 immunoblot (IB) analysis of total lysates from the Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusion strain Φ(−655 to +220) overproducing the indicated AtfJ HTH mutants. Ponceau S staining (protein) shows a separate region of the membrane as a loading control. Numbers at the left of the blot indicate molecular masses (in kilodaltons). (C) Swarm radius of P. mirabilis HI4320 overexpressing atfJ, atfJ-His6, or specified AtfJ alanine substitution mutants grown to late logarithmic phase and spotted on swarm agar. The swarm radius measured for HI4320 containing the empty vector plasmid (pLX3607 [+e.v.]) was set to 100%, and all other measurements were normalized to this value. Asterisks indicate the degree of statistical significance compared to results for the strain containing atfJ-His6. Statistical significance was calculated based on the raw values. (D) Strains were grown with IPTG to induce plasmid expression, as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in the text. Activities were normalized to the Miller unit value obtained for the strain containing atfJ (+atfJ), which was set to 100%. Asterisks indicate degrees of statistical significance in a comparison with the strain containing atfJ. Statistical significance was calculated based on the raw values (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001); error bars represent SDs.

We next measured the ability of these mutants to activate expression of the Φ(atfAp-lacZ) promoter fusion containing nucleotides −655 to +220 (Fig. 3D) and observed widely differing effects on promoter activation. Mutation of both residues predicted to be involved in salt bridge formation (R20 and E45) abrogated AtfJ activity. Similarly, replacement of glutamine residue 39 with alanine resulted in a strongly diminished autoregulatory response. In general, substitutions within the conserved core (S37 to E45) impaired AtfJ autoregulatory function more strongly than mutation of residues outside this region. Some of these core residues (e.g., Q39 and S42) are predicted to form the sequence-specific binding site, but other residues in this region (e.g., S37 and Q38) do not yet have a predicted function. Interestingly, some mutants that were impaired in motility repression retained the ability to autoregulate atf (the G27A mutant and, to a lesser extent, the R46A mutant). Our results confirm that the residues within the HTH are important for the function of AtfJ, although their contributions toward swarming and activation of atfAp expression appear to differ.

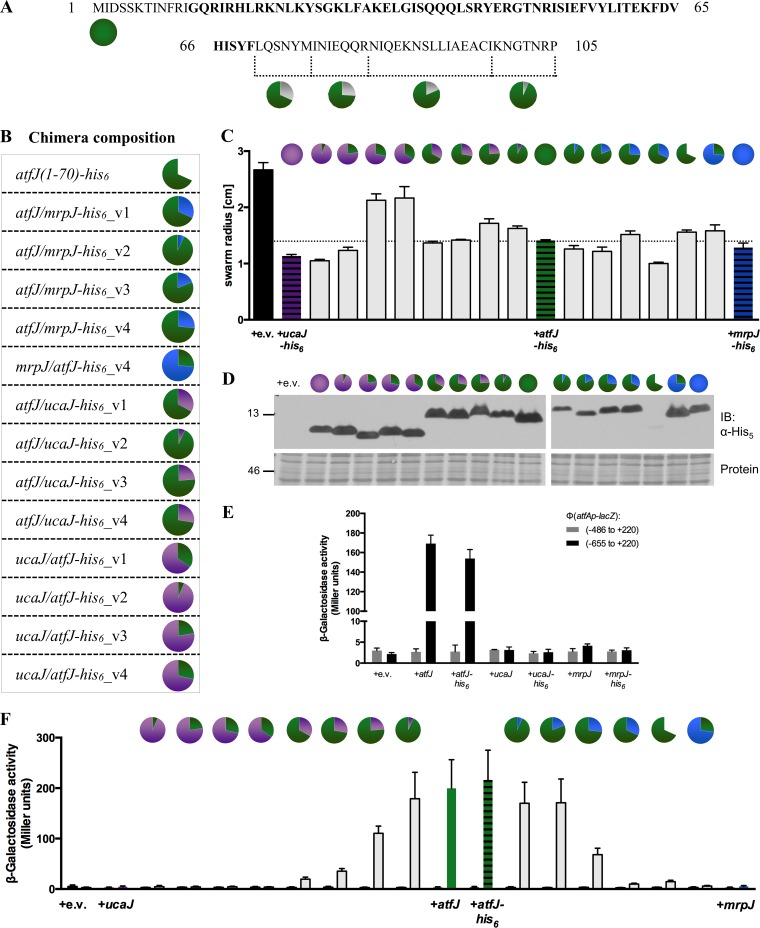

Swarm repression and autoregulation by AtfJ are not invariably linked.

Interestingly, the paralogs contain unique N- and C-terminal extensions of various lengths. In silico analysis predicted multiple α-helices within the secondary structures of AtfJ, MrpJ, and UcaJ (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), which, despite their apparent sequence variation, formed proteins with similar, if not identical, structures. In designing our chimeric fusion proteins, we attempted to preserve all secondary-structure elements to retain protein stability. Thus, we avoided fusions at the N-terminal border of the predicted HTH motif, which might result in misfolded proteins. Instead, we focused our efforts on the C terminus of the MrpJ paralogs to assess the importance of this domain for protein function. We made derivatives with fusion points at either the end of the HTH motif, the beginning of the C-terminal α-helix, or in between these two elements. Last, we swapped out the C-terminal 7 amino acids with an equal number of residues from a second paralog. The amino acid sequences for all chimeric proteins used in this study are listed in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material. In Fig. 4, we use a pie chart system to refer to the individual chimeras: the coloration refers to the ratio of the two proteins that make up the chimera, with the color on the left half identifying the N terminus of the fusion. All chimeric fusions were cloned with C-terminal His6 tags into the vector pLX3607 to allow for detection by immunoblotting and were tested for functionality in swarm assays. Any strains producing fusion proteins that exhibited the bull's-eye swarm phenotype characteristic of wild-type P. mirabilis, indicating that the mutated protein was nonfunctional, were excluded from further analysis.

FIG 4.

The C terminus of AtfJ is required for induction of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) expression. (A) Sequence of AtfJ, with the predicted HTH motif in bold type. Pie charts indicate the fusion points used in the generation of chimeric paralog proteins. (B) Table depicting names and corresponding pie chart symbols of all tested chimeras. (C) Chimeric proteins retain the ability to repress swarm motility. Swarm radii are shown for P. mirabilis HI4320 overexpressing the indicated epitope-tagged wild-type paralogs or chimeric fusions grown to late logarithmic phase and spotted on swarm agar. (D) Anti-His5 immunoblot analysis of strains used in motility analysis. Cultures were grown with IPTG induction and whole-cell lysates prepared as described in Materials and Methods. “Protein” refers to a Ponceau S total protein stain, which serves as a loading control. Numbers at the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons). (E) Lack of transactivation of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) by UcaJ and MrpJ. Specified operon fusion strains were transformed with plasmids expressing ucaJ (pMP125), mrpJ (pLX3805), or their epitope-tagged counterparts (ucaJ-His6, pNB001; mrpJ-His6, pNB010). Strains were grown with IPTG induction, and β-galactosidase activities were determined as outlined in Materials and Methods. (F) Induction of Φ(atfAp-lacZ) expression by chimeric AtfJ paralogs. Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusion strains Φ(−655 to +220) and Φ(−486 to +220) were transformed with pLX3607 plasmid derivatives containing the indicated fusion proteins. Cultures were grown with IPTG, and β-galactosidase activities were measured as outlined in Materials and Methods. For all strains, the left bar represents the activity measured for operon fusion Φ(−486 to +220), while the right bar depicts the activity observed for operon fusion Φ(−655 to +220).

As shown in Fig. 4C, with the exception of fusion proteins UcaJ-AtfJ-His6_v1 and UcaJ-AtfJ-His6_v4, all chimeras retained the ability to repress motility at levels similar to those observed for wild-type AtfJ-His6. We decided to nevertheless include these proteins in our analysis, as their swarm phenotype mimicked the radial pattern described for the His6-tagged wild-type proteins mentioned above (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Notably, a variant of AtfJ truncated at the end of the HTH, AtfJ(1–70)-His6, did not exhibit diminished functionality in our motility assays, an observation consistent with previously published MrpJ data (10). Wild-type levels of motility repression for the AtfJ truncation are particularly striking, as the immunoblot showed markedly lower levels of this protein than those of AtfJ-His6 (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, the Ponceau S total protein stain of the same membrane showed a band of approximately the correct size that appeared to indicate larger protein levels than those detected by immunoblotting, suggesting that the truncation obstructs antigen availability (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Importantly, all chimeras were produced at comparable levels when the cultures were induced with IPTG (Fig. 4D). Consequently, these data suggest that the C-terminal domain of MrpJ paralogs is not important for motility repression.

We next examined the ability of our fusion proteins to activate the expression of atfA using our operon-lacZ reporter fusion strains. All plasmids were transformed into the operon fusion strains with the two longest promoter fragments [Φ(−655 to +220) with high β-galactosidase activity and Φ(−486 to +220) with background levels of activity]. Importantly, of the three proteins used to generate the chimeric fusions, only AtfJ showed activity in our reporter assays, while neither UcaJ, MrpJ, nor their His6-tagged counterparts transactivated the atfA promoter (Fig. 4E).

We then tested the autoregulatory activities of our engineered chimeric proteins. Expression of the AtfJ-responsive Φ(−655 to +220) operon fusion decreases with the amount of C-terminal AtfJ sequence replaced by a second MrpJ paralog, indicating that this region of AtfJ is required for its autoregulatory activity (Fig. 4F). Reverse-swap chimeras, in which MrpJ or UcaJ contained C-terminal amino acids of AtfJ, failed to show a gain of function in our reporter assay, suggesting that the C terminus of AtfJ is necessary but not sufficient for autoregulation.

Identification of residues critical for AtfJ autoregulatory function.

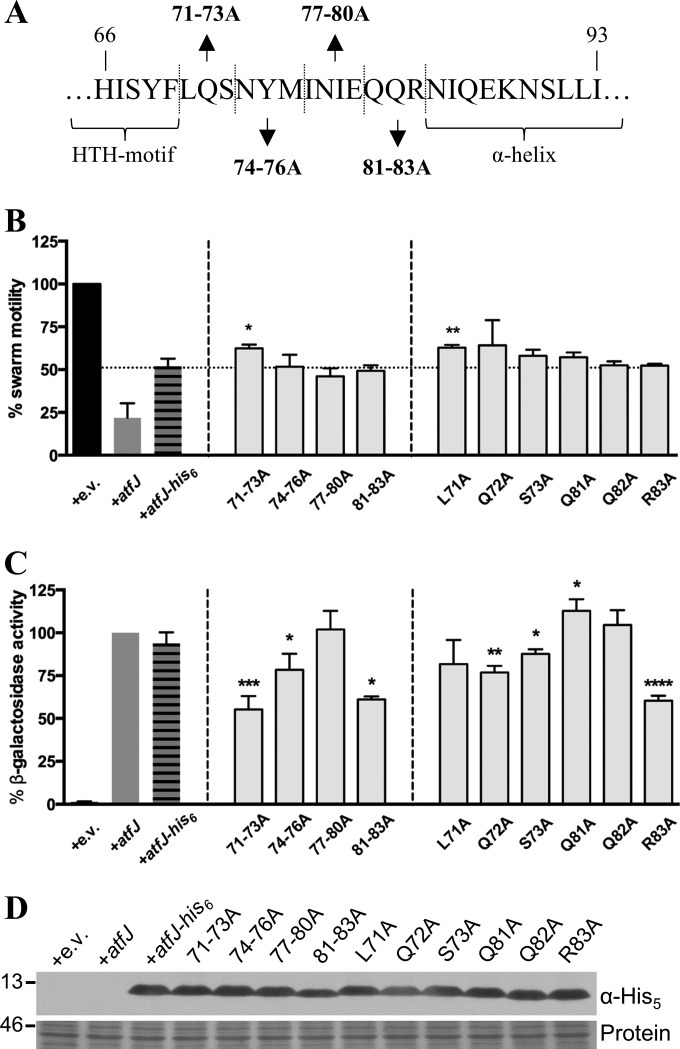

Having identified a portion of AtfJ that is critical for its autoregulatory activity but dispensable for motility repression, we next determined whether individual residues within this region were responsible for the observed phenotype. Therefore, we performed alanine scanning mutagenesis on AtfJ residues 71 to 83, as replacement of these residues in our chimeras resulted in a precipitous drop in measured Φ(atfAp-lacZ) activity (79.1% and 4.5% of AtfJ-His6 activity for AtfJ-MrpJ-His6_v3 and AtfJ-MrpJ-His6_v1, respectively) (Fig. 4F). We initially constructed four AtfJ mutants (Fig. 5A) in which three or four sequential amino acids were replaced with alanine and tested their activity, as outlined above. Expectedly, these mutants retained the ability to suppress swarm motility at levels comparable, if not identical, to wild-type AtfJ-His6 levels (Fig. 5B). In contrast, two of the mutants, AtfJ(71–73A) and AtfJ(81–83A), displayed significantly diminished autoregulation (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the C terminus of AtfJ. (A) Amino acid sequence surrounding the C-terminal end of the AtfJ HTH indicating positions of relevant C-terminal alanine substitution mutants. (B) Swarm radius of P. mirabilis HI4320 overexpressing atfJ, atfJ-His6, or specified AtfJ mutants grown to late logarithmic phase and spotted on agar. The swarm radius measured for HI4320 pLX3607 (+e.v.) was set to 100%, and all other measurements were normalized to this value. Asterisks indicate degrees of statistical significance in a comparison with the strain producing AtfJ-His6 (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01). Raw values were used to calculate statistical significance. (C) Plasmid expression was induced with IPTG as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described above. The strain containing atfJ was set to have 100% activity, and the activities of all other strains were normalized to this value. Asterisks indicate degrees of statistical significance in a comparison with the strain containing atfJ (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; and ****, P ≤ 0.0001). Statistical significance was calculated based on the raw values; error bars represent SDs. (D) Anti-His5 immunoblot analysis of total lysates from Φ(atfAp-lacZ) operon fusion strain Φ(−655 to +220) overproducing the indicated C-terminal AtfJ mutants. Ponceau S staining (Protein) shows a separate region of the membrane as a loading control. Numbers at the left indicate molecular masses (in kilodaltons).

Next, we performed single-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the amino acid residues contained within these two triple mutants to further tease apart their effects on AtfJ function. Of the 6 single AtfJ mutants, only a substitution of L71 resulted in a diminished capacity to repress swarming (Fig. 5B). With regard to autoregulation, we observed additive effects for the single-amino-acid substitutions of residues 71 to 73, as the replacement of all three residues caused defects, albeit to a lesser degree than those caused by the triple mutant (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, decreased autoregulation of AtfJ(81–83A) was recapitulated by a single-amino-acid substitution of alanine for arginine residue 83, while mutation of the remaining two residues did not impair Φ(atfAp-lacZ) expression (Fig. 5C). Immunoblot analysis determined that all of the amino acid changes described in this section were well tolerated, resulting in equal protein levels (Fig. 5D).

AtfJ directly binds the promoter fragment required for autoregulation.

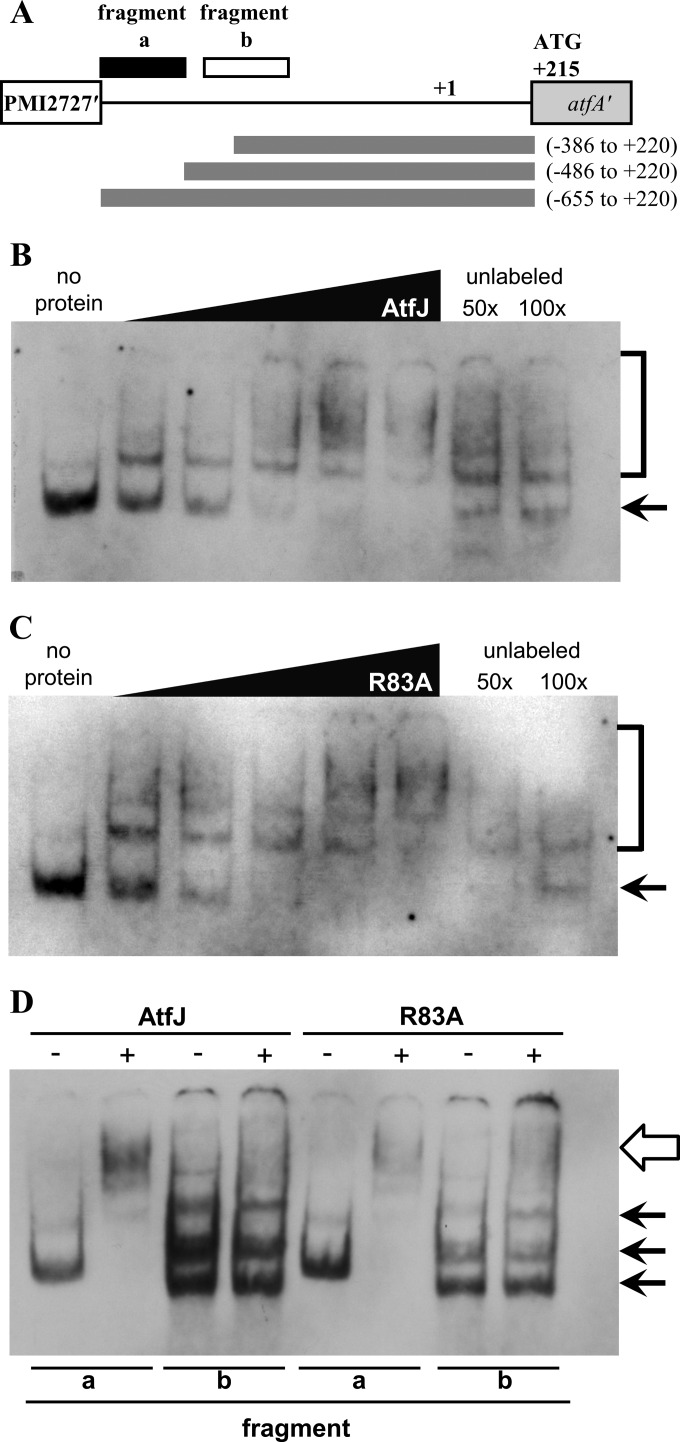

To determine whether AtfJ directly binds to the atfA promoter to control the expression of its own operon, we amplified the AtfJ-responsive fragment identified in Fig. 2 and used this 169-bp region (fragment a, nucleotides −655 to −487) (Fig. 6A) in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). A region of the same length located closer to the transcriptional start site of atfA was used as a control (fragment b, nucleotides −446 to −278). We observed that AtfJ-His6 interacted with the identified AtfJ-responsive fragment but not with the downstream control (Fig. 6B and D). Interestingly, the R83A mutant retained the ability to bind this DNA fragment (Fig. 6C and D), suggesting that R83 has a function other than DNA binding. The interactions that we observed were specific, as binding by both AtfJ and R83A was efficiently abrogated by addition of excess unlabeled DNA probe (Fig. 6B and C).

FIG 6.

Binding of AtfJ or AtfJ R83A to the atfA promoter. (A) atfA promoter schematic indicating the position of the gel shift probes relative to the promoter fusions assayed in Fig. 2. (B and C) EMSA of purified wild-type AtfJ (B) or the R83A mutant (C) incubated with a DIG-labeled AtfJ-responsive fragment (fragment a). In lane 1, no protein was added; in lanes 2 to 6, 2-fold serial dilutions of AtfJ-His6 or the R83A mutant, starting with 100 ng in lane 6, were incubated with a DIG-labeled DNA probe, and protein-DNA complexes were resolved by 6% native PAGE gels. In lanes 7 and 8, 100 ng of the indicated protein was incubated with a 50- or 100-fold excess of unlabeled fragment a. Arrows indicate free probe, and brackets indicate shifted probe. (D) EMSA in which 100 ng of AtfJ or the R83A mutant was incubated with DIG-labeled AtfJ-responsive promoter DNA (fragment a) or a DIG-labeled control probe (fragment b). Black arrows indicate free probe, and the open arrow points to the shifted probe.

Additionally, we tested three other equally sized overlapping fragments to map binding along the whole promoter (fragment c, nucleotides −313 to −145; fragment d, nucleotides −188 to −20; and fragment e, nucleotides −62 to +107). In doing so, we noted the exceptionally low GC content of parts of the promoter (see Fig. S7A in the supplemental material), which differs considerably from that of fragment a (30.8% GC content) and the chromosomal average (38.9% GC content) (9). We observed minimal binding to fragment c. However, AtfJ bound both probes closest to atfA (fragments d and e) (see Fig. S7B). While fragment d encompasses the region with slightly increased activity in our reporter assays [Φ(atfAp-lacZ) fusion strain containing nucleotides −106 to +220]) (Fig. 2C), binding to fragment e was unexpected. To examine the specificity of binding, we competed excess (100-fold) unlabeled probes of fragments a to e against labeled fragment a (see Fig. S7C). Unlike results with fragments b and c, the addition of fragment d or e partially reversed the fragment a shift. We conclude that AtfJ binding of fragment a is central to activation of the atf promoter, consistent with the reporter assay data. However, there may be a secondary AtfJ binding site on the overlapping fragments d and e.

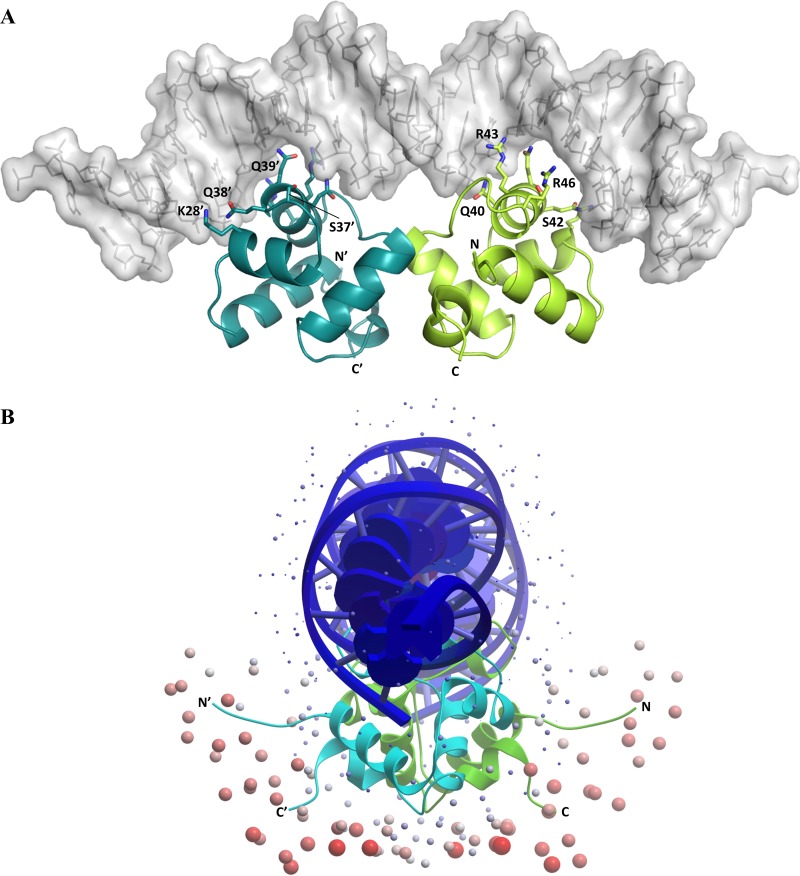

We generated a three-dimensional (3D) structural model of an AtfJ dimer bound to DNA (Fig. 7; see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material) by threading its sequence onto the structure of a homologous HTH protein in complex with DNA. This model suggested that the side chains of residues K28, Q38, Q39, Q40, S42, R43, and R46 are likely involved in DNA binding (Fig. 7A), consistent with our finding that this part of AtfJ is required for both motility repression and autoregulation. ODA analysis of this model also supports the hypothesis that the C-terminal domain of AtfJ contributes to regulation by another non-DNA-binding mechanism, as it predicts R83 involvement in protein-protein interaction (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Structural model of P. mirabilis AtfJ. (A) Computational model of AtfJ in complex with DNA (viewed from the side of the DNA). The AtfJ dimer (cyan and green) is shown as ribbons, and DNA is shown as gray surfaces. The recognition helix (H3) of each protomer is sitting in a DNA major groove, and DNA-binding residues, as well as those conserved within the HTH motif of all MrpJ paralogs, are shown in stick representation. (B) ODA analysis of the molecular model of AtfJ (viewed along the DNA). ODA uses desolvation energy to accurately predict sites of protein-protein interactions, and spheres are placed at the surface of the protein. The redness and size of the spheres are proportional to the region's likelihood of being involved in protein-protein interactions. This result indicates that the N- and C-terminal regions in AtfJ are likely involved in interactions with other proteins.

DISCUSSION

Reciprocal regulation of the two antagonistic forces of flagellum-mediated motility and fimbrial adhesion is essential for uropathogens to successfully establish a foothold in their host, where the bacteria may encounter variable osmolarity, urine flow, specialized epithelial cells, and innate immune effectors (7, 8). The ability to quickly adapt to an ever-changing environment is critical to promote bacterial survival and is at least partially conferred at the level of transcription. With its accessible structure and reactive nature, RNA is well suited to act as a transient messenger, aiding in minimizing the energy costs of producing superfluous proteins. The half-lives of bacterial RNAs range from a fraction of a minute to an hour (35), turnover rates that can be achieved only by careful orchestration of both global and operon-specific regulatory proteins (36). Bacteria living in more-diverse environments, such as the urinary tract, encode a larger relative fraction of transcription factors than those living in stable niches (37, 38). Nevertheless, the initial discovery of 15 MrpJ-type regulators in P. mirabilis, the majority of which repress motility, was striking (10).

Fimbriae facilitate adherence to a variety of abiotic and biotic surfaces. Given their direct interaction with specific host tissues, many fimbriae have been identified as important virulence factors (3). With 17 potential chaperone-usher fimbriae, several of which can be produced simultaneously (18, 39–42), P. mirabilis encodes the largest number of this type of fimbria in a single genome of any bacterium sequenced to date (9), while also showing an unusually high degree of fimbrial conservation within a collection of clinical isolates (26). Consequently, several fimbrial proteins, such as the major subunit MrpA or the tip adhesin MrpH, have been the subjects of a number of vaccine studies (43–49).

Previous studies have begun to elucidate the environmental conditions that regulate the production of fimbriae in P. mirabilis. For example, oxygen-limiting conditions have long been known to increase fimbriation in a variety of bacterial species, including P. mirabilis (40, 42, 50, 51). Additionally, the expression of mrp is highly upregulated early in infection (1 and 3 days postinfection) but less so at a later time point (7 days postinfection). Interestingly, the transcription of two other fimbrial operons, pmf and fim8, is downregulated in vivo, possibly hinting at the existence of a fimbrial hierarchy (17). The MrpJ paralogs associated with 10 of the potential operons encoding chaperone-usher fimbriae are excellent candidates to mediate this regulation. Here, we provide molecular evidence that multiple MrpJ paralogs are capable of altering the transcription of other fimbrial genes (Fig. 1). Furthermore, our qRT-PCR studies show conclusively that autoregulation is not limited to MrpJ, as both AtfJ and Fim8J induce expression of their own operons. However, it appears that this capacity is limited to a subset of MrpJ paralogs, as UcaJ did not elicit a similar response (Fig. 1).

We expanded our knowledge of how MrpJ and its paralogs function by mechanistically probing AtfJ and its operon, atf. Surprisingly, we found negligible levels of the atfA transcript in our reporter assays in the absence of AtfJ (Fig. 2C). This is likely owed to the significant divergence of the identified −35 region from the consensus σ70 promoter (Fig. 2B) (34), as intrinsic promoter strength is largely determined based on the extent of conservation of the core promoter (52, 53). For comparison, we observed markedly higher LacZ levels when expression is driven by the core promoter elements of mrp, each of which differs from the consensus by only one position (24). Traditionally, most transcriptional activators of σ70 promoters are thought to bind the immediate vicinity of the −35 element, often establishing direct contacts with domain 4 or the C terminus of RNA polymerase, resulting in an increased rate of transcription initiation (54, 55). This was not the case for the AtfJ-responsive element that we identified in our reporter assays (at nucleotides −655 to −487), which is located at a site distal to the one that we reported for MrpJ on the mrp promoter (24).

How might AtfJ binding of this distal site drive transcription? A deepened appreciation of the higher-order structure of bacterial chromatin, which is assembled in large part by nucleoid-associated proteins, has altered our view to include longer-range interactions that allow effective communications beyond distances of 1 kb (56, 57). One possibility suggested by the combination of the R83 mutational experiments (Fig. 5C) and ODA analysis (Fig. 7B) is that an unknown cofactor binds the C-terminal domain of AtfJ and forms a bridge with RNA polymerase. A second hypothesis hinted at by our EMSA data (see Fig. S7B in the supplemental material) involves the presence of secondary or cooperative AtfJ binding sites closer to the −35 site.

While we observed AtfJ binding to a promoter fragment surrounding the core promoter −10 and −35 binding sites in vitro (fragment e) (see Fig. S7B in the supplemental material), fusion of the same region to lacZ did not elicit a measurable response. However, the EMSA shift of partially overlapping fragment d correlates with the small but significant increase in reporter activity of the region from nucleotides −106 to +220. Notably, we also observed AtfJ-independent reporter activity for this fragment, which may be caused by the deletion of adjacent repressor elements. Though we cannot rule out any position-dependent effects caused by the integration of operon fusion constructs at a nonnative site, it is possible that the promoter elements proximal to the transcriptional start site of atfA are less accessible to AtfJ in vivo. Binding to the upstream element may result in a conformational change that exposes downstream elements, thereby allowing increased recruitment of RNA polymerase by a class I or class II activator mechanism (54). Interestingly, work on MrpJ demonstrated the existence of combined proximal and distal binding sites at two target promoters (mrp and flhD), suggesting that this mechanism of transcriptional regulation may be conserved across the different paralogs (24).

At least two MrpJ paralogs, UcaJ and MrpJ itself, repress motility by binding directly to the promoter of the flagellar master regulator flhD (10). Although it remains to be shown that AtfJ regulates motility in this fashion, our mutagenesis data support this hypothesis, as replacement of any one of the residues predicted to contribute to DNA binding relieved swarm repression (Fig. 3C). Our analysis of both the conserved HTH motif and the unique C-terminal tail of AtfJ (Fig. 3 to 5) identified several mutations that affected only one of the protein's two functions, demonstrating that autoregulation and motility repression are not invariably linked in this MrpJ paralog. Given the sequence diversity observed at the N and C termini of the 15 MrpJ paralogs, the ability to interact with a variety of binding partners might explain how these proteins carry out their overlapping, but nonidentical, roles.

Although our study establishes fimbrial autoregulation as a larger theme in P. mirabilis, many questions remain unanswered. Promoters serve as the point of signal convergence and, as is the case for promoters dependent on the actions of two or more activators, are often bound simultaneously by multiple regulatory proteins that do not interact with each other (54). This built-in plasticity allows for complex responses in response to varied environmental stimuli, which may be regulated by multiple MrpJ paralogs at the same promoter. Repression of a complex cellular phenotype, such as swarming, by different modes of action (10) raises the possibility that integration of the activities of several MrpJ paralogs causes a robust regulatory response to change from a motile to an adherent phenotype whenever necessary. Although MrpJ was recently suggested to be the apex regulator of the P. mirabilis fimbrial hierarchy (24), it remains to be demonstrated whether other paralogs take over this role in later stages of infection, when mrp expression is less elevated (17). Furthermore, we speculate that MrpJ paralogs, which likely all form dimers, as predicted here for AtfJ (Fig. 7), might form heterodimers, which might greatly increase the combinatorial potential of these transcriptional regulators.

In conclusion, we have examined the role of AtfJ as a dual regulator of motility and adherence in P. mirabilis. Our studies provide an explanation for the unusual maintenance of 15 homologous genes within this uropathogen's 4-Mb genome. Future work will need to be devoted to uncovering the full extent of Proteus interfimbrial connectivity and how it relates to pathogenesis. Only then will we be able to judge the full potential of targeting fimbrial appendages with vaccines or anti-infectives.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jessica Schaffer and Andrew Darwin for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Allison Norsworthy and Irina Debnath for critical reading of a draft version of this paper. We thank Georg Kosche for his assistance in photographing the swarm motility plates.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00193-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Commichau FM, Stulke J. 2015. Trigger enzymes: coordination of metabolism and virulence gene expression. Microbiol Spectr 3. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0010-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg EP. 2000. Bacterial genomics. Pump up the versatility. Nature 406:947–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blomfield I, van der Woude M. April 2007, posting date Regulation of fimbrial expression. EcoSal Plus 2007. doi: 10.1128/ecosal.2.4.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearns DB. 2010. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:634–644. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mobley HLT, Belas R. 1995. Swarming and pathogenicity of Proteus mirabilis in the urinary tract. Trends Microbiol 3:280–284. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)88945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffer JN, Pearson MM. 2015. Proteus mirabilis and urinary tract infections. Microbiol Spectr 3. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0017-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielubowicz GR, Mobley HLT. 2010. Host-pathogen interactions in urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol 7:430–441. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armbruster CE, Mobley HLT. 2012. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM, Abdellah Z, Arrosmith C, Atkin B, Chillingworth T, Hauser H, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Norbertczak H, Rabbinowitsch E, Walker D, Whithead S, Thomson NR, Rather PN, Parkhill J, Mobley HLT. 2008. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J Bacteriol 190:4027–4037. doi: 10.1128/JB.01981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson MM, Mobley HLT. 2008. Repression of motility during fimbrial expression: identification of 14 mrpJ gene paralogues in Proteus mirabilis. Mol Microbiol 69:548–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massad G, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 1994. Proteus mirabilis fimbriae: construction of an isogenic pmfA mutant and analysis of virulence in a CBA mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun 62:536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zunino P, Sosa V, Allen AG, Preston A, Schlapp G, Maskell DJ. 2003. Proteus mirabilis fimbriae (PMF) are important for both bladder and kidney colonization in mice. Microbiology 149:3231–3237. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zunino P, Sosa V, Schlapp G, Allen AG, Preston A, Maskell DJ. 2007. Mannose-resistant Proteus-like and P. mirabilis fimbriae have specific and additive roles in P. mirabilis urinary tract infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 51:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Himpsl SD, Lockatell CV, Hebel JR, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 2008. Identification of virulence determinants in uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis using signature-tagged mutagenesis. J Med Microbiol 57:1068–1078. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/002071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pellegrino R, Scavone P, Umpiérrez A, Maskell DJ, Zunino P. 2013. Proteus mirabilis uroepithelial cell adhesin (UCA) fimbria plays a role in the colonization of the urinary tract. Pathog Dis 67:104–107. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahrani FK, Massad G, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Russell RG, Warren JW, Mobley HLT. 1994. Construction of an MR/P fimbrial mutant of Proteus mirabilis: role in virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun 62:3363–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson MM, Yep A, Smith SN, Mobley HLT. 2011. Transcriptome of Proteus mirabilis in the murine urinary tract: virulence and nitrogen assimilation gene expression. Infect Immun 79:2619–2631. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05152-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massad G, Bahrani FK, Mobley HLT. 1994. Proteus mirabilis fimbriae: identification, isolation, and characterization of a new ambient-temperature fimbria. Infect Immun 62:1989–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zunino P, Geymonat L, Allen AG, Legnani-Fajardo C, Maskell DJ. 2000. Virulence of a Proteus mirabilis ATF isogenic mutant is not impaired in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 29:137–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen AM, Lockatell V, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 2004. Mannose-resistant Proteus-like fimbriae are produced by most Proteus mirabilis strains infecting the urinary tract, dictate the in vivo localization of bacteria, and contribute to biofilm formation. Infect Immun 72:7294–7305. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7294-7305.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder JA, Haugen BJ, Lockatell CV, Maroncle N, Hagan EC, Johnson DE, Welch RA, Mobley HLT. 2005. Coordinate expression of fimbriae in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 73:7588–7596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7588-7596.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuccio SP, Chessa D, Weening EH, Raffatellu M, Clegg S, Bäumler AJ. 2007. SIMPLE approach for isolating mutants expressing fimbriae. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:4455–4462. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00148-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Rasko DA, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 2001. Repression of bacterial motility by a novel fimbrial gene product. EMBO J 20:4854–4862. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bode NJ, Debnath I, Kuan L, Schulfer A, Ty M, Pearson MM. 2015. Transcriptional analysis of the MrpJ network: modulation of diverse virulence-associated genes and direct regulation of mrp fimbrial and flhDC flagellar operons in Proteus mirabilis. Infect Immun 83:2542–2556. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02978-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckman KL, Pease LR. 2007. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc 2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuan L, Schaffer JN, Zouzias CD, Pearson MM. 2014. Characterization of 17 chaperone-usher fimbriae encoded by Proteus mirabilis reveals strong conservation. J Med Microbiol 63:911–922. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.069971-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobley HLT, Belas R, Lockatell V, Chippendale G, Trifillis AL, Johnson DE, Warren JW. 1996. Construction of a flagellum-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: effect on internalization by human renal epithelial cells and virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun 64:5332–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2013. Scalable Web services for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W349–W357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abagyan R, Batalov S, Cardozo T, Totrov M, Webber J, Zhou Y. 1997. Homology modeling with internal coordinate mechanics: deformation zone mapping and improvements of models via conformational search. Proteins 1997(Suppl 1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Recio J, Totrov M, Skorodumov C, Abagyan R. 2005. Optimal docking area: a new method for predicting protein-protein interaction sites. Proteins 58:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konkel ME, Tilly K. 2000. Temperature-regulated expression of bacterial virulence genes. Microbes Infect 2:157–166. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dufour A, Furness RB, Hughes C. 1998. Novel genes that upregulate the Proteus mirabilis flhDC master operon controlling flagellar biogenesis and swarming. Mol Microbiol 29:741–751. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feklistov A, Sharon BD, Darst SA, Gross CA. 2014. Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belasco JG. 2010. All things must pass: contrasts and commonalities in eukaryotic and bacterial mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:467–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Hijum SA, Medema MH, Kuipers OP. 2009. Mechanisms and evolution of control logic in prokaryotic transcriptional regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:481–509. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00037-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cases I, de Lorenzo V. 2005. Promoters in the environment: transcriptional regulation in its natural context. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrgard MJ, Covert MW, Palsson BO. 2004. Reconstruction of microbial transcriptional regulatory networks. Curr Opin Biotechnol 15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adegbola RA, Old DC, Senior BW. 1983. The adhesins and fimbriae of Proteus mirabilis strains associated with high and low affinity for the urinary tract. J Med Microbiol 16:427–431. doi: 10.1099/00222615-16-4-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahrani FK, Mobley HLT. 1994. Proteus mirabilis MR/P fimbrial operon: genetic organization, nucleotide sequence, and conditions for expression. J Bacteriol 176:3412–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolson DL, Barrigar DL, McLean RJ, Altman E. 1995. Expression of a nonagglutinating fimbria by Proteus mirabilis. Infect Immun 63:1127–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Old DC, Adegbola RA. 1982. Haemagglutinins and fimbriae of Morganella, Proteus and Providencia. J Med Microbiol 15:551–564. doi: 10.1099/00222615-15-4-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Lane MC, Warren JW, Mobley HLT. 2004. Development of an intranasal vaccine to prevent urinary tract infection by Proteus mirabilis. Infect Immun 72:66–75. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.66-75.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Erbe JL, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Jobling MG, Holmes RK, Mobley HLT. 2004. Use of translational fusion of the MrpH fimbrial adhesin-binding domain with the cholera toxin A2 domain, coexpressed with the cholera toxin B subunit, as an intranasal vaccine to prevent experimental urinary tract infection by Proteus mirabilis. Infect Immun 72:7306–7310. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7306-7310.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pellegrino R, Galvalisi U, Scavone P, Sosa V, Zunino P. 2003. Evaluation of Proteus mirabilis structural fimbrial proteins as antigens against urinary tract infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 36:103–110. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scavone P, Miyoshi A, Rial A, Chabalgoity A, Langella P, Azevedo V, Zunino P. 2007. Intranasal immunisation with recombinant Lactococcus lactis displaying either anchored or secreted forms of Proteus mirabilis MrpA fimbrial protein confers specific immune response and induces a significant reduction of kidney bacterial colonisation in mice. Microbes Infect 9:821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scavone P, Rial A, Umpiérrez A, Chabalgoity A, Zunino P. 2009. Effects of the administration of cholera toxin as a mucosal adjuvant on the immune and protective response induced by Proteus mirabilis MrpA fimbrial protein in the urinary tract. Microbiol Immunol 53:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scavone P, Sosa V, Pellegrino R, Galvalisi U, Zunino P. 2004. Mucosal vaccination of mice with recombinant Proteus mirabilis structural fimbrial proteins. Microbes Infect 6:853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scavone P, Umpiérrez A, Maskell DJ, Zunino P. 2011. Nasal immunization with attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium expressing an MrpA-TetC fusion protein significantly reduces Proteus mirabilis colonization in the mouse urinary tract. J Med Microbiol 60:899–904. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.030460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Old DC, Duguid JP. 1970. Selective outgrowth of fimbriate bacteria in static liquid medium. J Bacteriol 103:447–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lane MC, Li X, Pearson MM, Simms AN, Mobley HLT. 2009. Oxygen-limiting conditions enrich for fimbriate cells of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 191:1382–1392. doi: 10.1128/JB.01550-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szoke PA, Allen TL, deHaseth PL. 1987. Promoter recognition by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: effects of base substitutions in the −10 and −35 regions. Biochemistry 26:6188–6194. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi M, Nagata K, Ishihama A. 1990. Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: effect of base substitutions in the promoter −35 region on promoter strength. Nucleic Acids Res 18:7367–7372. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Browning DF, Busby SJ. 2004. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee DJ, Minchin SD, Busby SJ. 2012. Activating transcription in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:125–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorman CJ. 2013. Genome architecture and global gene regulation in bacteria: making progress towards a unified model? Nat Rev Microbiol 11:349–355. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bondarenko VA, Liu YV, Jiang YI, Studitsky VM. 2003. Communication over a large distance: enhancers and insulators. Biochem Cell Biol 81:241–251. doi: 10.1139/o03-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.