ABSTRACT

CD4+ T cells play a central role in orchestrating adaptive immunity. To better understand the roles of CD4+ T cells in the effects of adjuvants, we investigated the efficacy of a T-dependent influenza virus split vaccine with MF59 or alum in CD4 knockout (CD4KO) and wild-type (WT) mice. CD4+ T cells were required for the induction of IgG antibody responses to the split vaccine and the effects of alum adjuvant. In contrast, MF59 was found to be highly effective in raising isotype-switched IgG antibodies to a T-dependent influenza virus split vaccine in CD4KO mice or CD4-depleted WT mice equivalent to those in intact WT mice, thus overcoming the deficiency of CD4+ T cells in helping B cells and inducing immunity against influenza virus. Vaccination with the MF59-adjuvanted influenza virus vaccine was able to induce protective CD8+ T cells and long-lived antibody-secreting cells in CD4KO mice. The effects of MF59 adjuvant in CD4KO mice might be associated with uric acid, inflammatory cytokines, and the recruitment of multiple immune cells at the injection site, but their cellularity and phenotypes were different from those in WT mice. These findings suggest a new paradigm of CD4-independent adjuvant mechanisms, providing the rationales to improve vaccine efficacy in infants, the elderly, immunocompromised patients, as well as healthy adults.

IMPORTANCE MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccines were licensed for human vaccination, but the detailed mechanisms are not fully elucidated. CD4+ T cells are required to induce antibody isotype switching and long-term memory responses. In contrast, we discovered that MF59 was highly effective in inducing isotype-switched IgG antibodies and long-term protective immune responses to a T-dependent influenza vaccine independent of CD4+ T cells. These findings are highly significant for the following reasons: (i) MF59 can overcome a defect of CD4+ T cells in inducing protective immunity to vaccination with a T-dependent influenza virus vaccine; (ii) a CD4-independent pathway can be an alternative mechanism for certain adjuvants such as MF59; and (iii) this study has significant implications for improving vaccine efficacies in young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised populations.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccination is used to induce protective antibodies and immune memory to prevent against future pathogens. Adjuvants can play a key role in the development of successful vaccines by enhancing immunogenicity and leading to antigen dose-sparing effects, fewer immunizations, and long-lasting B and T cell immunity. Aluminum hydroxide (alum) has been the most common adjuvant used in human vaccines for >70 years. Alum may act via various mechanisms such as antigen depot, benign cell death (1), and recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages partially through inflammasome signaling pathways (2, 3). An inflammasome pathway of alum adjuvant effects is controversial due to the lack of evidence in vivo (4, 5). MF59 is an oil-in-water emulsion adjuvant licensed in 1997 and has been used in influenza vaccines (6). MF59 increases the production of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines and recruits various innate immune cells such as neutrophils and monocytes at the injection site (7).

The activation of T cells depends on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs) of the innate immune system. It has been well established that CD4+ T cells provide critical help for inducing long-lived protective antibody production by B cells (8) and for generating effective CD8+ memory T cells (9). Thus, it is believed that the effects of adjuvants on enhancing antibody responses to T cell-dependent vaccine antigens are mediated by CD4+ T helper cells through adjuvant-activated innate immune components, as demonstrated in many studies (10–16). A conventional concept is that adjuvants activate innate immune components, which subsequently determines the specific type of T helper cell for orchestrating the quantity and quality of protective antibodies (13, 17, 18). However, the roles of CD4+ T cells in the effects of adjuvants and underlying mechanisms by which adjuvants work remain largely unknown.

In this study, we addressed the basic question of whether the effects of adjuvants would be dependent on CD4+ T cells in generating protective immunity. Using licensed adjuvants (alum and MF59) for use in human vaccines and a T-dependent influenza virus split vaccine, adaptive immune components and efficacy of protection were determined in wild-type (WT) and CD4-deficient (CD4 knockout [CD4KO]) mouse models. In contrast to the effects of alum adjuvant requiring CD4+ T cells, we demonstrated that MF59 was effective in mediating the induction of protective antibody responses in the absence of conventional CD4+ T cells. We have further investigated and discussed possible mechanisms of the effects of adjuvants on generating protective immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents.

Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 WT and CD4KO (B6.129S6-Cd4tm1Knw/J) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained in the Georgia State University (GSU) animal facility under the guidelines of a GSU-approved IACUC protocol (protocol A14025). The commercial influenza virus split vaccine (Green Flu-S; Green Cross, South Korea) was derived from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic A/California/07/2009 virus strain. Alum adjuvant was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and MF59 was provided as a gift from Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Inc. (Cambridge, MA).

Immunization and virus infection.

C57BL/6 WT and CD4KO mice were intramuscularly immunized two times with the split vaccine only (1 μg of hemagglutinin [HA]) or the split vaccine plus alum (50 μg/mouse) or MF59 (50% [vol/vol], as recommended by manufacturer) with a 4-week interval. Five months after boost immunization, mice were intranasally challenged with a lethal dose (20× 50% lethal dose [LD50]) of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus. Body weight changes were monitored for 14 days.

Antibody and cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

Immune sera were collected 3 weeks after each immunization and used to determine IgG antibody levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), as described previously (19). Briefly, serially diluted immune sera were applied to ELISA plates coated with inactivated virus (2 μg/ml). After washing, horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary anti-mouse antibody reagents were used to detect antigen-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c antibodies. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used as a substrate, and the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm by using an ELISA reader (Bio-Rad). For analysis of long-lived antibody-secreting-cell responses, bone marrow (BM) cells and spleen cells were harvested from mice at day 5 post-virus infection and incubated in influenza virus-coated cell culture plates for 1 or 5 days. Levels of antibodies secreted in vitro were measured by an ELISA. For measurement of cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung extracts, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) Ready-Set-Go kits (eBioscience) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Hemagglutination inhibition assay.

Immune sera were incubated with receptor-destroying enzymes (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 18 h and then at 56°C for 30 min for complement inactivation. Inactivated sera were serially diluted and incubated with 8 HA units of A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) virus in V-bottom microplates. After 30 min, 0.5% chicken red blood cells were added to the wells, and hemagglutination was determined after 40 min. The detection limit for the determination of hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers was 2 log2 units.

In vivo protection assay of immune sera.

Naive and immune sera were incubated at 56°C for 30 min for inactivation of complements and diluted 4 times with phosphate-buffer saline (PBS). Diluted sera were mixed with a lethal dose (7.5× LD50) of A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) virus and incubated for 30 min. A mixture of serum and virus was used to infect naive WT mice intranasally. Body weight changes of the infected mice were monitored daily for 14 days.

Lung virus titration.

Lung extracts were prepared for the determination of viral titers by using a mechanical tissue grinder with 1.5 ml of PBS per lung. Embryonated chicken eggs were inoculated with diluted lung extracts and incubated at 37°C for 3 days. The allantoic fluids of eggs were collected, and hemagglutination assays were performed to determine viral titers. Virus titers expressed as 50% egg infectious doses (EID50) per milliliter were evaluated according to the method of Reed and Muench (20). The detection limit for the determination of EID50 was 1.7 log10 units.

Histology.

Intact lungs from immunized mice were harvested at day 5 post-virus infection and treated with formalin for fixation. The fixed lung tissues were processed, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (21). Photographs were acquired with a microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 100) with an attached camera at a ×100 magnification (Canon 30D).

CD8+ cell and CD4+ cell depletion.

Five months after boost immunization, MF59-adjuvanted CD4KO mice were treated with anti-mouse CD8α monoclonal antibodies (150 μg/mouse; clone 53-6.7) intraperitoneally (i.p.) on days −2 and +1 relative to the day of challenge. The mice were challenged with a lethal dose of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and sacrificed at day 5 postinfection to determine the roles of CD8+ T cells in protection against virus infection. Naive WT mice were injected with an anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal antibody (200 μg/mouse; clone GK1.5) intraperitoneally 2 days before prime and boost immunizations. Mice were further administered CD4-depleting antibodies every 7 days to maintain the CD4 depletion status.

Intraperitoneal injection of adjuvants and flow cytometry.

WT and CD4KO mice (n = 5 each) received i.p. injection of PBS (200 μl), alum (50 μg in 200 μl), or MF59 (100 μl in 200 μl). Sera were collected at 1.5, 6, and 24 h postinjection and stored at −80°C until analysis. Peritoneal exudates were harvested at 24 h postinjection. The sera and peritoneal exudates were used to perform cytokine/chemokine ELISAs according to the manufacturer's instructions. Peritoneal cells were treated with Fc receptor blocker (anti-CD16/32) and then stained with fluorescence-labeled CD11b (clone M1/70), CD11c (clone N418), F4/80 (clone BM8), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) (clone M5/114.15.2), Ly6c (clone HK1.4), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), SiglecF (clone E50-2440), CD3 (clone 17A2), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), and pan-natural killer (NK) cell marker CD49b (clone DX5) antibodies. Fluorescent antibody-stained cells were acquired by using a BD Fortessa instrument (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) and analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). Macrophages (CD11b+ F4/80+), MHC-IIhigh macrophages (CD11b+ F4/80+ MHC-IIhigh), monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6chigh F4/80+), neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6c+ F4/80−), eosinophils (CD11b+ SiglecF+), plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) (CD11c+ B220+ MHC-IIhigh), CD11bhigh DCs (CD11c+ CD11bhigh MHC-IIhigh), CD11blow DCs (CD11c+ CD11blow MHC-IIhigh), CD4+ T cells (CD3+ CD4+), CD8+ T cells (CD3+ CD8+), natural killer T (NKT) cells (CD49b+ CD3+), and NK cells (CD49b+ CD3−) were gated by flow cytometry.

Cell death analysis.

BM-derived DCs (BMDCs) and BM-derived macrophages (BMMs) were prepared from WT C57BL/6 mice as described previously (22, 23). Briefly, bone marrow cells were cultured with mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/ml) for 6 days to enrich BMDCs or with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (25 ng/ml) for 7 days to enrich BMMs. Cell viability was determined by using the [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium] bromide (MTT) assay to measure the activity of mitochondrial dehydrogenase. DC2.4 cells, kindly provided by Martin D'Souza, were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates. Cells were treated with alum (50 μg) or MF59 (50%) for 24 h, and the cells were harvested. The cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Uric acid assay.

Peritoneal exudates were harvested from PBS-, MF59-, or alum-injected WT or CD4KO mice at 24 h postinjection. Uric acid levels in peritoneal exudates were measured by using a uric acid assay kit (Bioassay system) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis.

All results are presented as means ± SEM (standard errors of the means). Statistical significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test or 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. We analyzed all data with Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

MF59 is effective in generating influenza vaccine-specific isotype-switched IgG antibodies in CD4-deficient mice.

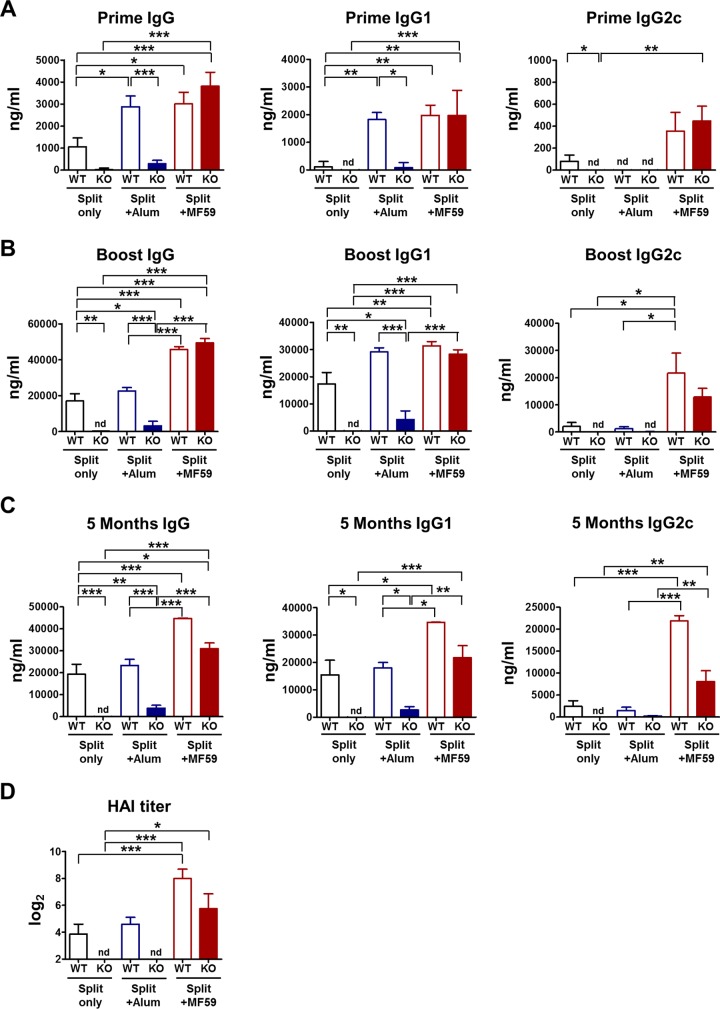

To determine the roles of CD4+ T cells in the effects of adjuvants on generating vaccine-specific isotype-switched antibodies, WT and CD4KO mice were intramuscularly immunized with the influenza split vaccine alone or in combination with MF59 or alum adjuvant. Immunization with the split vaccine only induced IgG1-dominant antibody responses at low levels in WT mice but no antibody responses in CD4KO mice (Fig. 1), indicating that antibody responses to the split vaccine require CD4+ T cell help. Similarly, the alum treatment group showed significantly lower levels of IgG and IgG1 antibodies in CD4KO mice than did WT mice (Fig. 1), suggesting a CD4+ T cell dependency of the effect of alum adjuvant. The MF59 treatment group generated vaccine-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c antibodies at substantial levels after priming of CD4KO mice, which were significantly higher than those in WT mice immunized with the split vaccine alone (Fig. 1A). Vaccination of WT mice with the split vaccine alone and with the split vaccine plus alum induced IgG1-dominant antibodies, indicating T helper type 2 (Th2) immune responses, whereas vaccination of CD4KO mice with the split vaccine plus MF59 induced both IgG1 and IgG2c isotypes similar to those in WT mice, eliciting Th1- and Th2-type immune responses regardless of CD4+ T cells. In addition, MF59-adjuvanted CD4KO mice induced IgG and IgG1 antibodies specific for the vaccine at significantly higher levels than those in WT mice immunized with the split vaccine alone and the split vaccine plus alum after boost immunization (Fig. 1B). In general, CD4+ T cells are required for long-lived antibody and memory responses. Surprisingly, the antibody levels in CD4KO mice immunized with the split vaccine plus MF59 were maintained 5 months after boost immunization (Fig. 1C), suggesting the induction of long-lived IgG isotype-switched antibodies in the absence of conventional CD4+ T cells. The levels of IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c in CD4KO mice immunized with the split vaccine plus MF59 were comparable to those in WT mice administered MF59 (Fig. 1). HAI assays were performed to determine whether protective antibodies would be induced in immune sera (Fig. 1D). The split vaccine alone or with alum induced low HAI titers in WT mice and no HAI titers in CD4KO mice. The MF59 treatment group exhibited high HAI titers in CD4KO mice, which were comparable to those in WT mice, indicating that MF59 adjuvant vaccination induces protective HAI antibodies in the absence of CD4+ T cells. In addition, CD4-independent induction of isotype-switched IgG antibodies was similarly observed in CD4-depleted WT mice vaccinated with MF59 plus the split vaccine (Fig. 2). These results for the effects of adjuvant on CD4KO mice suggest that MF59 can overcome CD4+ T cell deficiency in raising IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a isotype-switched and functional (HAI) antibodies specific for the split vaccine, a T-dependent antigen.

FIG 1.

CD4KO mice treated with MF59 are more effective in inducing IgG isotype antibodies than are WT mice treated with the split vaccine alone or with alum. Immune sera were taken 3 weeks after each immunization from WT and CD4KO mice (n = 10 per group) intramuscularly immunized with the split vaccine with or without alum or MF59 adjuvant. Inactivated A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus-specific IgG and isotype-switched IgG antibody levels in immune sera were determined by ELISAs. (A to C) Antibody levels after prime (A) and boost (B) immunizations and 5 months after boost (C) immunization are presented as means ± SEM. (D) HAI titers were determined in immune sera from WT and CD4KO mice immunized with the split vaccine with or without alum or MF59 adjuvant. WT, C57BL/6 wild-type mice (n = 10); KO, CD4 knockout mice (n = 10). Results are representative of data from duplicate experiments. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison tests. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; nd, not detected.

FIG 2.

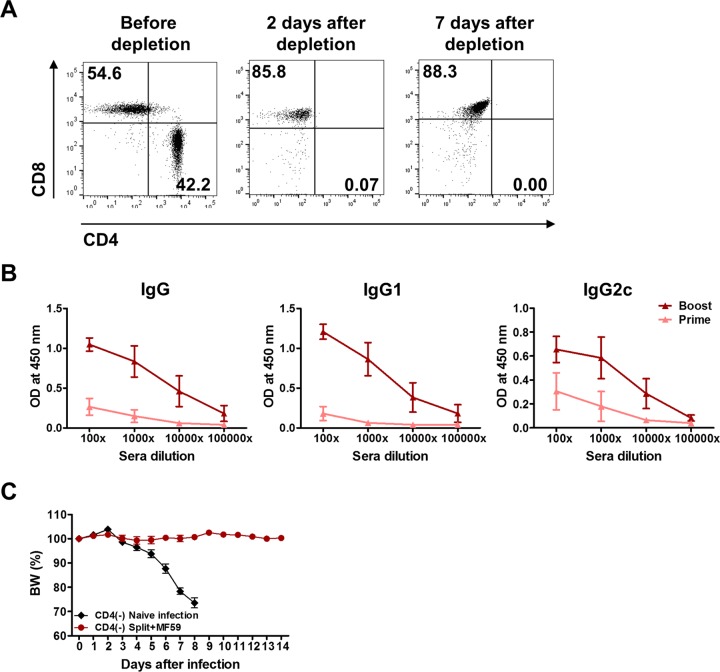

Induction of protective isotype-switched antibodies by vaccination of CD4-depleted B6 WT mice with MF59 adjuvant plus the split vaccine. (A) Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were injected with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (200 μg/mouse; clone GK1.5) to deplete CD4+ T cells. Cells were harvested from blood samples of CD4-depleted mice to determine CD4 depletion. CD4 and CD8 marker profiles from CD3+ gated T cells are shown. (B) CD4-depleted WT mice were immunized 2 times (prime and boost) with the split vaccine plus MF59. CD4 depletion was maintained by additional weekly treatments with CD4-depleting antibodies during immunization. Two weeks after each immunization, immune sera were collected to determine virus-specific IgG and isotype-switched IgG antibody levels by an ELISA. (C) Naive and immune mice were infected with a lethal dose of virus 4 weeks after boost immunization. Body weight (BW) changes were monitored for 14 days.

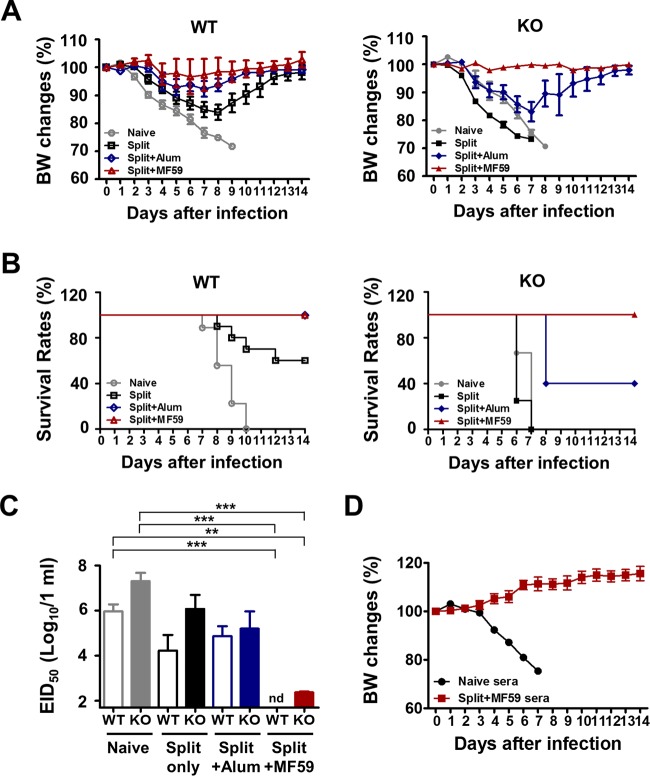

Vaccination with the split vaccine plus MF59 but not alum induces equivalent protection in CD4KO and WT mice.

To investigate the effects of adjuvant on conferring protection, 5 months after boost vaccination, immunized WT and CD4KO mice were intranasally challenged with a lethal dose of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus. WT mice treated with the split vaccine alone were severely sick, as shown by >18% weight loss and 60% survival rates, indicating a low efficacy of protection. CD4KO mice treated with the split vaccine were not protected (Fig. 3A and B). The effects of the alum adjuvant were evident in WT mice, with moderate weight loss of ∼8%, but ineffective in CD4KO mice, which displayed >18% weight loss and 40% survival rates (Fig. 3A and B). The effects of MF59 adjuvant on conferring 100% protection without weight loss in CD4KO mice were similar to those in WT mice (Fig. 3A and B). Consistent with the protective effects of MF59 in CD4KO mice, we observed 100% protection, without weight loss, against lethal infection in CD4-depleted WT C57BL/6 (B6) mice (Fig. 2C). To better assess protective efficacy, lung viral titers were determined at day 5 post-virus infection (Fig. 3C). The groups administered the split vaccine and alum adjuvant showed high lung viral loads in both CD4KO and WT mice. The MF59 treatment group showed the lowest lung viral titers in both CD4KO and WT mice. These results suggest that MF59 but not alum adjuvant was effective in conferring protection independent of CD4+ T cell help even 5 months after vaccination in a mouse model.

FIG 3.

Vaccination with MF59 plus the split vaccine confers equal protection in CD4KO and WT mice. (A and B) Body weight (BW) changes (A) and survival rates (B) after lethal A/California/2009 (H1N1) influenza virus challenge after 5 months of vaccination. (C) Lung virus titers in embryonated chicken eggs at day 5 postinfection expressed as EID50. The detection limit for determination of the EID50 was 1.7 log10 units. (D) In vivo protective effects of immune sera. Naive mice were intranasally infected with a lethal dose (7.5× LD50) of virus (A/California/04/2009 [H1N1]) mixed with immune sera from naive CD4KO mice or CD4KO mice vaccinated with the split vaccine plus MF59. WT, wild-type C57BL/6 mice (n = 10); KO, CD4 knockout mice (n = 10). Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (for comparisons among groups). nd, not detected.

In addition, we determined the protective roles of immune sera from CD4KO mice that were immunized with the split vaccine plus MF59 (Fig. 3D). Naive mice were intranasally infected with a mixture of a lethal dose of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and immune sera or naive sera and monitored daily (Fig. 3D). All mice that were infected with the mixture of virus and naive sera died of infection by day 7, whereas mice infected with virus and immune sera from CD4KO mice that received vaccination with the split vaccine and MF59 did not show any weight loss, and 100% survived (Fig. 3D). Therefore, antibodies induced by vaccination of CD4KO mice with the split vaccine plus MF59 can confer protection to naive mice.

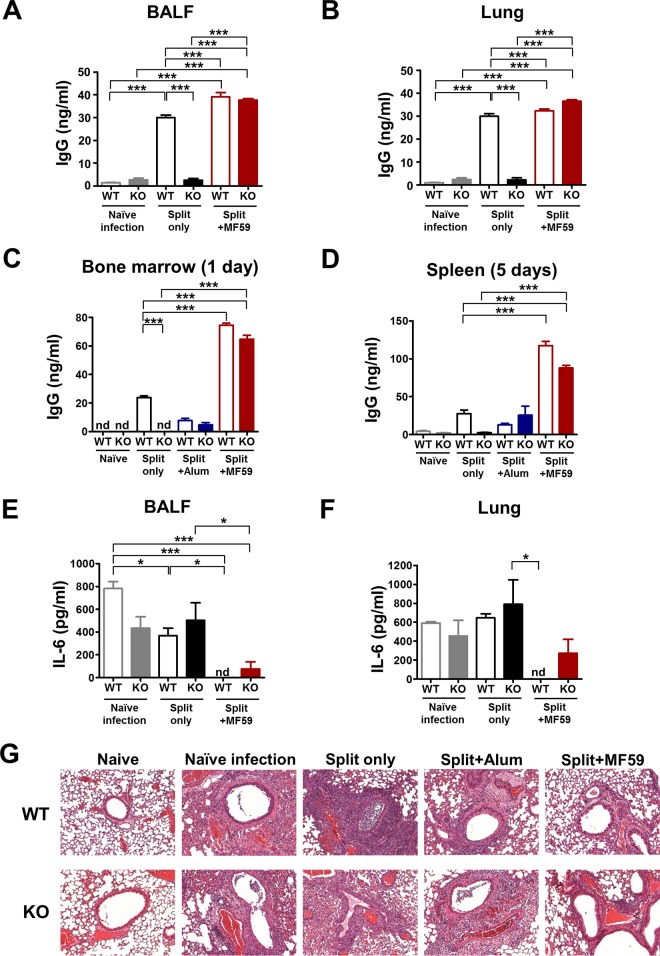

MF59 but not alum is effective in generating antibody-secreting long-lived cells in both CD4KO and WT mice.

Antibody secretion at the infection site plays a role in blocking virus invasion and replication. WT mice treated with the split vaccine with or without adjuvants showed IgG antibodies in BALF (Fig. 4A) and lung extracts (Fig. 4B) at day 5 after infection. However, CD4KO mice administered the split vaccine only did not display IgG antibodies in BALF and lung extracts collected at day 5 after infection (Fig. 4A and B). CD4+ T cell-independent antibody responses are characterized as being short-lived within 30 days and deficient of long-lived plasma cells in BM (24, 25). To determine whether MF59 contributes to the generation of long-lived plasma cells and memory-type B cells, in vitro antibody production was determined by using cells of BM and spleens collected from immune mice after virus infection at 5 months of vaccination (Fig. 4C and D). The WT mouse groups immunized with the split vaccine only and the split vaccine plus alum showed low levels of antibodies from 1-day BM or 5-day spleen cell cultures (Fig. 4C and D). Surprisingly, MF59-treated CD4KO mice showed significantly high levels of antibodies in cultures of BM and spleen cells, which were comparable to those in MF59-treated WT mice (Fig. 4C and D). These results suggest that MF59 adjuvant contributes to the generation of long-lived antibody-secreting-cell responses even without help from CD4+ T cells.

FIG 4.

Vaccination of CD4KO mice with MF59 plus the split vaccine induces mucosal antibodies and long-lived plasma and memory B cell responses and protects against lung inflammation after virus challenge. (A) IgG levels in BALF. (B) IgG levels in lung extracts. (C and D) BM and spleen cells were harvested at day 5 postinfection after 5 months of vaccination. BM cells (C) and spleen cells (D) were cultured in plates coated with virus antigen for 1 day and 5 days, respectively, and IgG levels were detected by an ELISA. (E) IL-6 inflammatory cytokine levels in BALF. (F) IL-6 inflammatory cytokine levels in lung extracts. BALF and lung samples (n = 5) were collected 5 days after lethal challenge. (G) Lung histopathology of mice (n = 5) after virus challenge. Lung tissues at day 5 postchallenge were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; (for comparisons among groups). nd, not detected.

Vaccination with MF59 plus the split vaccine protects against pulmonary inflammation in immune CD4KO and WT mice.

Pathogenic influenza virus infection inflames lung tissues by inducing excessive proinflammatory cytokines and/or recruiting immune cells. High levels of IL-6 were observed in BALF and lung extracts from the groups of naive WT mice, WT mice receiving the split vaccine only, and CD4KO mice receiving alum at day 5 after challenge (Fig. 4E and F). In contrast, low levels of IL-6 in BALF and lung extracts were detected in the MF59-treated CD4KO and WT groups (Fig. 4E and F). Histopathological changes in the lung were analyzed to better evaluate the protective efficacy of adjuvants after challenge of WT and CD4KO mice (Fig. 4G). Both WT and CD4KO naive mice showed severe lung inflammation upon influenza virus infection, as shown by extensive infiltrates around the airways, blood vessels, and interstitial spaces (Fig. 4G). Immune WT and CD4KO mice administered the split vaccine only and the split vaccine plus alum showed moderate to high levels of immune cell infiltration, and CD4KO mice displayed a tendency to have more severe inflammation than the corresponding WT mice (Fig. 4G). Importantly, MF59-adjuvanted WT and CD4KO mice showed the lowest level of or no overt pulmonary inflammation, which is consistent with effective protection in the MF59-adjuvanted WT and CD4KO groups. These data suggest that MF59 adjuvant vaccination effectively protects against lung inflammation due to viral infection, even in the absence of CD4+ T cell help.

CD4KO mice vaccinated with MF59 plus the split vaccine induce protective CD8+ T cells.

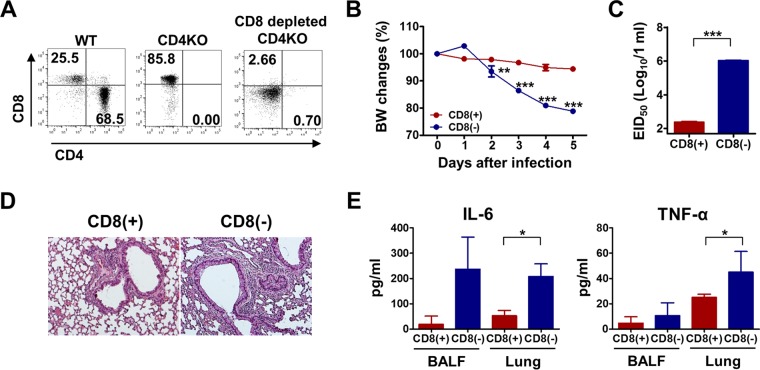

Since CD4+ T cells play an essential role in generating functionally effective CD8+ T cells, we determined whether MF59 contributes to the generation of protective CD8+ T cells in CD4KO mice. We applied a CD8 depletion approach to the MF59-adjuvanted group prior to virus challenge (Fig. 5A). The MF59-treated CD4KO group with CD8 depletion displayed ∼20% weight loss compared to the control MF59-treated CD4KO group, with 4 to 5% weight loss, after lethal virus infection (Fig. 5B). In addition, CD8+ T cell depletion in CD4KO mice immunized with the split vaccine plus MF59 led to 1,000-fold-higher egg infectious titers than those in the CD8-competent CD4KO group (Fig. 5C). In terms of lung inflammation, CD8-depleted CD4KO mice showed more severe pulmonary inflammation, as examined by histopathology (Fig. 5D), and higher levels of proinflammatory cytokine production in both BALF and lung extracts (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that MF59 adjuvant contributes to the generation of protective CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ T cells.

FIG 5.

MF59-adjuvanted CD4KO mice induce protective CD8+ T cell responses. (A) CD4KO mice immunized with the split vaccine plus MF59 were injected with an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (150 μg/mouse; clone 53-6.7) to deplete CD8+ T cells before virus challenge. Cells were harvested from blood samples of CD8-depleted mice 2 days after injection to determine CD8 depletion. CD4 and CD8 marker profiles from CD3+ gated T cells are shown. (B) Body weight changes of CD8-depleted CD4KO mice after virus infection. (C) Lung virus titers in embryonated chicken eggs at day 5 after infection. (D) Lung histopathology of CD8-depleted CD4KO mice at day 5 postinfection. (E) Inflammatory IL-6 and TNF-α cytokine levels in BALF and lung extracts at day 5 postinfection. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (for comparisons between CD8-depleted and CD8-undepleted CD4KO mouse groups [n = 5]).

MF59 induces in vivo inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in CD4KO and WT mice.

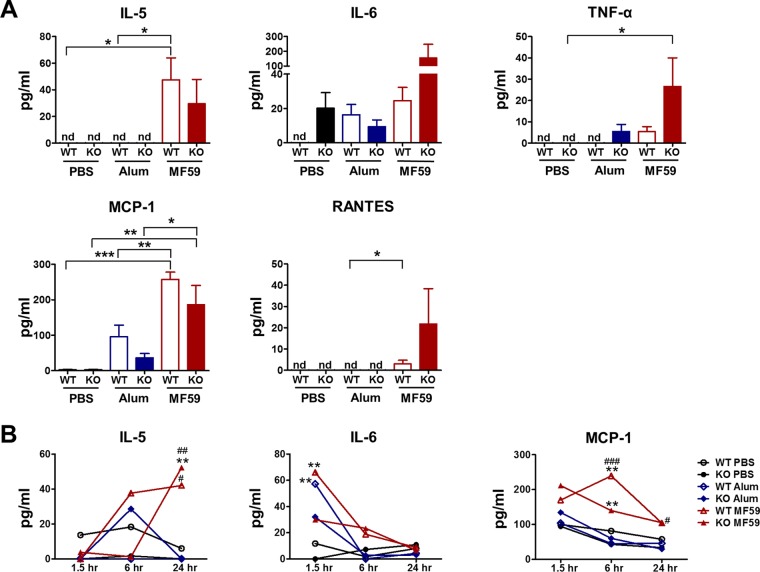

Certain adjuvants recruit innate immune cells, resulting in an immunocompetent microenvironment. To investigate the underlying CD4+ T cell-independent adjuvant mechanisms of MF59, we injected alum and MF59 intraperitoneally into WT and CD4KO mice. Sera at 1.5, 6, and 24 h and peritoneal exudates at 24 h were harvested after injection. Cytokines and chemokines in peritoneal exudates and sera were detected by an ELISA (Fig. 6A and B). MF59 induced high levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, and TNF-α) and chemokines (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1] and RANTES) in peritoneal exudates, whereas alum induced low levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 only (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, MF59-injected CD4KO mice showed high levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and RANTES and similar levels of IL-5 and MCP-1 compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that MF59 injection could induce a more inflammatory environment in CD4KO mice than that in WT mice. In addition to the local responses, systemic cytokine/chemokine levels were also higher in MF59-injected mice than those in PBS- or alum-injected mice (Fig. 6B). The IL-6 level in sera was rapidly increased at the early time point (1.5 h), but IL-5 was induced at high levels at late time points in sera from MF59-treated WT mice (6 h) and CD4KO mice (24 h) and maintained at high levels for a while. The level of MCP-1, a chemokine that recruits monocytes and DCs, was transiently increased in both MF59-injected WT and CD4KO mice.

FIG 6.

MF59 induces acute production of cytokines and chemokines at higher levels than does alum. WT and CD4KO mice (n = 5) were intraperitoneally injected with PBS, alum, or MF59. (A) Levels of cytokines and chemokines in peritoneal exudates 24 h after injection. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (for comparisons among groups). (B) Kinetics of cytokine and chemokine levels in sera from adjuvant-injected mice (n = 5 mice per group). Statistical significances were calculated by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttests. **, P < 0.01 (compared to the PBS-treated group). #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001 (compared to the alum-treated group). nd, not detected.

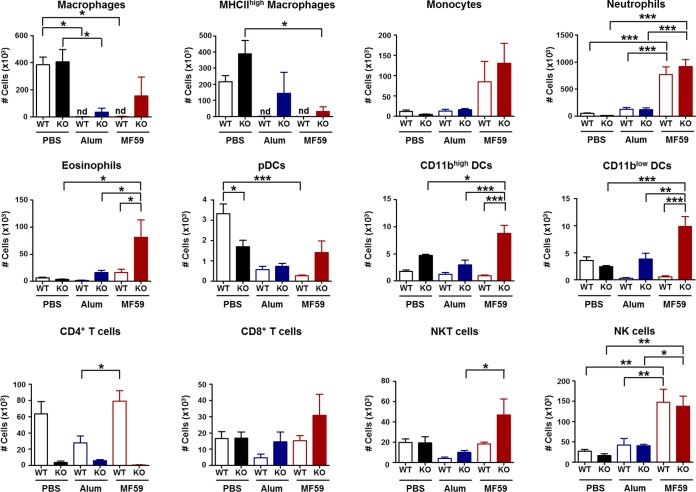

MF59 recruits multiple innate immune cells and dendritic cells in CD4KO mice.

To analyze the cellular phenotypes at the injection site, peritoneal cells were harvested 24 h after adjuvant injection. Most macrophages disappeared (or were depleted) in alum- and MF59-treated WT mice, whereas some macrophages were maintained in CD4KO mice treated with MF59 (Fig. 7). In contrast, levels of monocytes, neutrophils, and NK cells in MF59 adjuvant-treated CD4KO and WT mice were significantly higher than those in alum-treated mice. Surprisingly, CD4KO mice treated with MF59 showed higher cellularity of macrophages, eosinophils, NKT cells, as well as DC populations, including pDCs, CD11bhigh DCs, and CD11blow DCs, than did WT mice treated with MF59 (Fig. 7). These results suggest that differential cellularity and patterns of immune cell recruitment after MF59 treatment of WT mice and CD4KO mice may explain the CD4-independent and CD4-dependent effects of MF59 adjuvant and the superior adjuvanticity of MF59 over alum.

FIG 7.

Injection of MF59 in CD4KO mice acutely recruits multiple innate and dendritic cells. Cells in peritoneal exudates were collected 24 h after adjuvant injection, and their phenotypes and cellularity were determined by using flow cytometry (n = 5 mice per group). Macrophages are CD11b+ F4/80+, MHC-IIhigh macrophages are CD11b+ F4/80+ MHC-IIhigh, monocytes are CD11b+ Ly6chigh F4/80+, neutrophils are CD11b+ Ly6c+ F4/80−, eosinophils are CD11b+ SiglecF+, pDCs are CD11c+ B220+ MHC-IIhigh, CD11bhigh DCs are CD11c+ CD11bhigh MHC-IIhigh, CD11blow DCs are CD11c+ CD11blow MHC-IIhigh, CD4+ T cells are CD3+ CD4+, CD8+ T cells are CD3+ CD8+, NKT cells are CD49b+ CD3+, and NK cells are CD49b+ CD3−. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***; P < 0.001 (for comparisons among groups). nd, not detected.

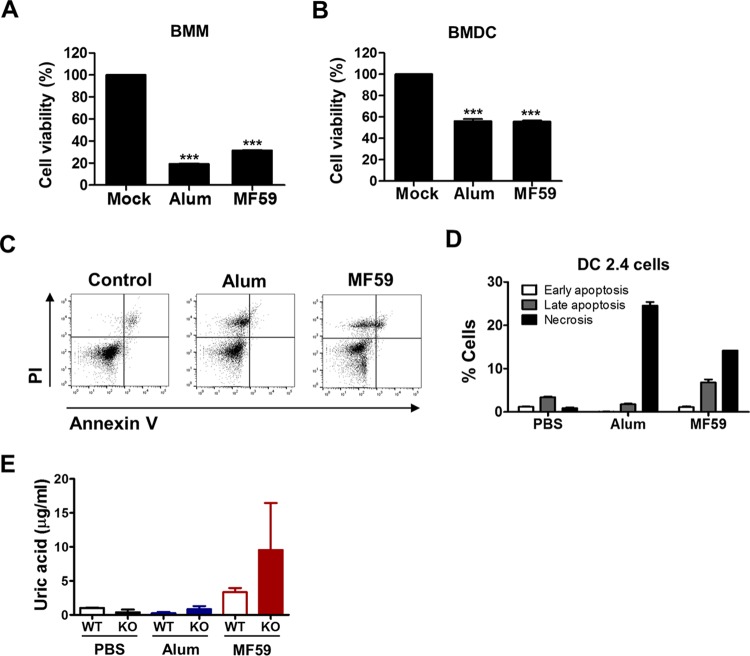

MF59 as well as alum adjuvants induce in vitro cell death and uric acid production.

Induction of cell death or tissue damage can be a mechanism for the effects of alum adjuvant (26–28). To investigate whether alum or MF59 adjuvant induces cell death, BMDCs and BMMs were cultured in vitro in the presence of adjuvant for 48 h, and cell viability was determined (Fig. 8A and B). BMMs showed ∼20% and 30% cell viability in the presence of alum and MF59 adjuvants, respectively (Fig. 8A). BMDCs treated with alum or MF59 resulted in 50% cell death (Fig. 8B). Alum- and MF59-treated DC2.4 cells showed ∼25% and 15% necrotic cell death, respectively (Fig. 8C and D). MF59-treated cells also displayed substantial cell death via apoptosis. Consistent with the in vitro cell death results, high levels of uric acid, a danger signal in response to cell death (29), were observed in the peritoneal exudates 24 h after injection of MF59 in WT and CD4KO mice (Fig. 8E). These in vitro results appear to be consistent with the lower cellularity in vivo of macrophages and DC populations at the site of alum or MF59 adjuvant injection.

FIG 8.

Alum and MF59 adjuvants induce in vitro cell death and uric acid production. (A and B) Cell viability of BMMs (A) and BMDCs (B) after in vitro culture with alum or MF59. Primary BMMs and BMDCs from C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of alum (100 μg/ml) or MF59 (20%) for 48 h, and cell viability was determined by an MTT assay. Statistical significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. ***, P < 0.01 compared to the mock control group. (C and D) Flow cytometry profiles (C) and apoptotic or necrotic cell death percentages (D) for DC2.4 cells. DC2.4 cells were treated with adjuvants for 24 h and then stained with annexin V and PI. Necrotic cell death was determined as PI-positive and annexin V-negative cells, late apoptosis was determined as PI-positive and annexin V-positive cells, and early apoptosis was determined as PI-negative and annexin V-positive cells. (E) WT and CD4KO mice were intraperitoneally injected with PBS, alum, or MF59. Peritoneal exudates were collected 24 h post-adjuvant injection, and uric acid levels were measured.

DISCUSSION

It is a conventional mechanism that most adjuvants activate components of the innate immune system, mediating the effective presentation of antigens via APCs, which subsequently determines a pattern of T helper cell immune responses (Th1, Th2, Th17, follicular T cells, and regulatory T cells). Activation of T helper cells and APCs via adjuvants provides a differential and critical role in controlling specific B cells to produce isotype-switched IgG antibodies. As expected, CD4+ T cells were found to be critical for inducing isotype-switched IgG antibodies by split vaccination and for the effects of alum adjuvant. Nonetheless, the efficacy of alum was low, as evidenced by the ineffective clearance of virus from lungs, lung inflammation, and weight loss in immunocompetent WT mice after virus challenge.

Different from the conventional dogma of the critical roles of CD4+ T cells in generating adaptive immunity, CD4+ T cells appear to be differentially required for inducing protective immunity, depending on the IgG isotypes and the types of adjuvants. Here, unexpectedly, we found that MF59 adjuvant could overcome a deficiency of CD4+ T cells in generating isotype-switched IgG antibodies and conferring effective protection even after 5 months of vaccination. CD4-independent IgG antibody responses induced by sublethal virus infection were shown to be short-lived within 30 days and to wane rapidly, and there were no antibody-secreting plasma cells (24, 25). IgG antibody responses in CD4KO mice treated with MF59 conferred protective immunity, high levels of virus-specific serum antibodies, and long-lived antibody-secreting plasma cells in BM even after 5 months. Also, the induction of protective humoral antibody and cellular CD8+ T cell responses was evident in CD4KO mice administered the split vaccine with MF59 adjuvant. Adaptive immune responses and efficacy of protection against influenza virus were significantly higher in CD4KO mice treated with MF59 than those in WT mice treated with the split vaccine alone or with alum. These results provide convincing clues that MF59 adjuvant may replace the roles of conventional CD4+ T cells in conferring protective immunity after T-dependent split vaccine immunization. This study suggests an alternative pathway between innate and adaptive immune systems via certain adjuvants such as MF59, which can be either a CD4-independent or CD4-dependent mechanism.

CD4KO mice were reported to develop MHC-II-restricted CD8+ T cells and double-negative T cells, which might contribute to providing CD4+ T cell-like help in CD4KO mice (30, 31). T cell receptor αβ-deficient mice were shown previously to have a severe defect in inducing IgG antibodies after vaccination (31). Nonetheless, an alternative approach of acute CD4 depletion in this study provides further evidence that MF59 can induce IgG isotype-switched antibodies in the absence of CD4+ T cells by eliminating the potential contribution of compensatory immune cells that might have developed in CD4KO mice. The possible roles of double-negative and/or γδ T cells in generating IgG antibodies in CD4KO mice remain to be determined.

Although it is not clear how MF59 works in a CD4-independent manner, possible mechanisms for the effects of MF59 adjuvant were reported previously. Alum and MF59 did not exhibit any in vitro stimulatory effects on DCs (3, 17). Intriguingly, the adjuvanticity of alum and MF59 in vivo required MyD88, a common signaling adaptor for most Toll-like receptors, using a MyD88 mutant mouse model with recombinant bacterial protein vaccines or ovalbumin model antigens (3, 32). MF59 was shown to create an immunocompetent microenvironment at the injection site by inducing chemokines and cytokines as well as recruiting neutrophils, eosinophils, and, later, DCs and macrophages (7). Previous studies on MF59 suggest that an immunocompetent microenvironment with activated innate immune cells and APCs leads to the induction of effector CD4+ T cells, eventually helping B cells to differentiate IgG antibody-secreting plasma cells (17, 33–35). By using microarray and immunofluorescence analyses, MF59 was determined to be a strong inducer of cytokines, cytokine receptors, adhesion molecules, and antigen-presenting genes and led to a rapid influx of CD11b+ blood cells (36). In this study, MF59 was more effective in inducing the acute production of IL-5 and MCP-1 than was alum. Compared to alum, MF59 was effective in attracting innate immune cells (monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils), APCs (CD11bhi/low DCs), NK cells, and NKT cells, which is consistent with data from a previous study (7). Interestingly, antibody-mediated neutrophil ablation did not alter MF59 adjuvanticity (7). MF59 induced higher levels of production of IL-6, TNF-α, and RANTES in CD4KO mice than those in WT mice. Thus, MF59 in CD4KO mice may work in a mechanism different from the one in WT mice. Larger DC populations, including pDCs and CD11bhi/low DCs, NKT cells, and CD8+ T cells, were recruited in CD4KO mice than in WT mice after MF59 treatment. Therefore, in the absence of CD4+ T cells, CD4KO mice might have differentially responded to MF59 adjuvant in their innate immune cells and cytokines, suggesting an alternative immune activation pathway in CD4KO mice.

Cell death sends danger signals such as uric acid and creates a local inflammatory microenvironment, triggering the innate immune system (29, 37). Necrotic sterile cell death or injury induces the generation of uric acid as an adjuvant, promoting adaptive immune responses (29, 38), and could be a powerful mediator of Th2-associated adjuvant effects (1). Most interestingly, we discovered that alum and MF59 injections resulted in the significant depletion of macrophages (F4/80+ CD11b+ MHC-IIlow/high) and pDCs in the peritoneal cavity in WT mice, possibly causing cell death of these particular cell types. In line with these results, substantial levels of uric acid were detected at the injection site in WT and particularly CD4KO mice (Fig. 8E). High levels of uric acid might be correlated with the inflammatory microenvironment producing IL-6, TNF-α, and RANTES in MF59-treated CD4KO mice.

In vitro cultures of primary BM-derived cells (BMMs and BMDCs) and DC2.4 DC lines with alum or MF59 displayed significant cell death. MF59 induced both apoptotic and necrotic cell death of DC2.4 cells, whereas alum displayed mostly necrotic cell death of the DC2.4 cell line. Compared to WT mice, i.p. injection of MF59 in CD4KO mice maintained substantial levels of macrophages and pDCs together with increased cellularity of CD11bhi/low DCs, which might contribute to the effects of MF59 adjuvant on CD4KO mice. These multiple mechanisms of MF59, which are different from those of alum quantitatively and qualitatively, appear to contribute to the induction of IgG isotype antibodies in CD4KO mice to levels comparable to those observed for WT mice.

The efficacy of influenza vaccines is low in young children and the elderly, who may have some defects in CD4+ T helper cells due to an immature immune system or aging. An MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccine was effective in infants and young children (39). Our present data are relevant to these clinical studies and have significant clinical applications in providing rationales to improve vaccine efficacy in young infants, the elderly, and CD4-deficient immunocompromised patients. Emerflu (an alum-adjuvanted, inactivated, split H5 hemagglutinin vaccine) is a symbolic failure of alum-adjuvanted influenza vaccines in adults (40), requiring more effective adjuvants. Another implication is that adjuvant studies using CD4KO mice may provide a model to search for effective adjuvants such as MF59. WT mice are likely to overrespond to experimental adjuvants and vaccines, which may not represent the efficacies expected in humans (41).

In conclusion, for the first time, this study demonstrated protective immunity induced by a T-dependent vaccine mediated by MF59 in CD4KO mice, which includes isotype-switched antibodies, long-lived IgG antibody-producing cells, protective HAI antibodies, and CD8+ T cells, conferring protection for over 5 months under CD4-deficient conditions. MF59 was more potent in acutely inducing inflammatory cytokines and in recruiting innate immune cells than was alum. Cell death and uric acid appear to be mechanisms for the adjuvant effects of MF59. Partial retention of macrophages from significant cell depletion and recruitment of DC populations in addition to monocytes and neutrophils at the site of injection might contribute to the effects of MF59 adjuvant, particularly in CD4KO mice. These findings suggest a new paradigm for the mechanisms of action of adjuvant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Gene Palmer (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Inc.) for kindly providing MF59 adjuvant and for critical reading of the manuscript and Suk Hoon Ha (Green Cross, Inc.) for providing the commercial influenza split monovalent vaccine.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobson LS, Lima H Jr, Goldberg MF, Gocheva V, Tsiperson V, Sutterwala FS, Joyce JA, Gapp BV, Blomen VA, Chandran K, Brummelkamp TR, Diaz-Griffero F, Brojatsch J. 2013. Cathepsin-mediated necrosis controls the adaptive immune response by Th2 (T helper type 2)-associated adjuvants. J Biol Chem 288:7481–7491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mbow ML, De Gregorio E, Valiante NM, Rappuoli R. 2010. New adjuvants for human vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol 22:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J. 2008. Cutting edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 181:3755–3759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKee AS, Munks MW, MacLeod MK, Fleenor CJ, Van Rooijen N, Kappler JW, Marrack P. 2009. Alum induces innate immune responses through macrophage and mast cell sensors, but these sensors are not required for alum to act as an adjuvant for specific immunity. J Immunol 183:4403–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franchi L, Nunez G. 2008. The Nlrp3 inflammasome is critical for aluminium hydroxide-mediated IL-1beta secretion but dispensable for adjuvant activity. Eur J Immunol 38:2085–2089. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Hagan DT, Ott GS, Nest GV, Rappuoli R, Giudice GD. 2013. The history of MF59 adjuvant: a phoenix that arose from the ashes. Expert Rev Vaccines 12:13–30. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabro S, Tortoli M, Baudner BC, Pacitto A, Cortese M, O'Hagan DT, De Gregorio E, Seubert A, Wack A. 2011. Vaccine adjuvants alum and MF59 induce rapid recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes that participate in antigen transport to draining lymph nodes. Vaccine 29:1812–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLennan IC, Gulbranson-Judge A, Toellner KM, Casamayor-Palleja M, Chan E, Sze DM, Luther SA, Orbea HA. 1997. The changing preference of T and B cells for partners as T-dependent antibody responses develop. Immunol Rev 156:53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1997.tb00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanolkar A, Badovinac VP, Harty JT. 2007. CD8 T cell memory development: CD4 T cell help is appreciated. Immunol Res 39:94–104. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galli G, Medini D, Borgogni E, Zedda L, Bardelli M, Malzone C, Nuti S, Tavarini S, Sammicheli C, Hilbert AK, Brauer V, Banzhoff A, Rappuoli R, Del Giudice G, Castellino F. 2009. Adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine induces early CD4+ T cell response that predicts long-term persistence of protective antibody levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:3877–3882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokolovska A, Hem SL, HogenEsch H. 2007. Activation of dendritic cells and induction of CD4(+) T cell differentiation by aluminum-containing adjuvants. Vaccine 25:4575–4585. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamath AT, Rochat AF, Christensen D, Agger EM, Andersen P, Lambert PH, Siegrist CA. 2009. A liposome-based mycobacterial vaccine induces potent adult and neonatal multifunctional T cells through the exquisite targeting of dendritic cells. PLoS One 4:e5771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAleer JP, Vella AT. 2010. Educating CD4 T cells with vaccine adjuvants: lessons from lipopolysaccharide. Trends Immunol 31:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee AS, Munks MW, Marrack P. 2007. How do adjuvants work? Important considerations for new generation adjuvants. Immunity 27:687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serre K, Mohr E, Benezech C, Bird R, Khan M, Caamano JH, Cunningham AF, Maclennan IC. 2011. Selective effects of NF-kappaB1 deficiency in CD4(+) T cells on Th2 and TFh induction by alum-precipitated protein vaccines. Eur J Immunol 41:1573–1582. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaspal FM, Kim MY, McConnell FM, Raykundalia C, Bekiaris V, Lane PJ. 2005. Mice deficient in OX40 and CD30 signals lack memory antibody responses because of deficient CD4 T cell memory. J Immunol 174:3891–3896. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Hagan DT, Ott GS, De Gregorio E, Seubert A. 2012. The mechanism of action of MF59—an innately attractive adjuvant formulation. Vaccine 30:4341–4348. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. 2010. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity 33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan FS, Vunnava A, Compans RW, Kang SM. 2010. Virus-like particle vaccine protects against 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus in mice. PLoS One 5:e9161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang HS, Kwon YM, Lee JS, Yoo SE, Lee YN, Ko EJ, Kim MC, Cho MK, Lee YT, Jung YJ, Lee JY, Li JD, Kang SM. 2014. Co-immunization with virus-like particle and DNA vaccines induces protection against respiratory syncytial virus infection and bronchiolitis. Antiviral Res 110:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YN, Lee YT, Kim MC, Hwang HS, Lee JS, Kim KH, Kang SM. 2014. Fc receptor is not required for inducing antibodies but plays a critical role in conferring protection after influenza M2 vaccination. Immunology 143:300–309. doi: 10.1111/imm.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YN, Kim MC, Lee YT, Hwang HS, Lee J, Kim C, Kang SM. 2015. Cross protection against influenza A virus by yeast-expressed heterologous tandem repeat M2 extracellular proteins. PLoS One 10:e0137822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee BO, Rangel-Moreno J, Moyron-Quiroz JE, Hartson L, Makris M, Sprague F, Lund FE, Randall TD. 2005. CD4 T cell-independent antibody response promotes resolution of primary influenza infection and helps to prevent reinfection. J Immunol 175:5827–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonti E, Fedeli M, Napolitano A, Iannacone M, von Andrian UH, Guidotti LG, Abrignani S, Casorati G, Dellabona P. 2012. Follicular helper NKT cells induce limited B cell responses and germinal center formation in the absence of CD4(+) T cell help. J Immunol 188:3217–3222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aimanianda V, Haensler J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. 2009. Novel cellular and molecular mechanisms of induction of immune responses by aluminum adjuvants. Trends Pharmacol Sci 30:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogenesch H. 2012. Mechanism of immunopotentiation and safety of aluminum adjuvants. Front Immunol 3:406. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kool M, Soullie T, van Nimwegen M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Jung S, Hoogsteden HC, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. 2008. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med 205:869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kono H, Chen CJ, Ontiveros F, Rock KL. 2010. Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice. J Clin Invest 120:1939–1949. doi: 10.1172/JCI40124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyznik AJ, Sun JC, Bevan MJ. 2004. The CD8 population in CD4-deficient mice is heavily contaminated with MHC class II-restricted T cells. J Exp Med 199:559–565. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sha Z, Compans RW. 2000. Induction of CD4(+) T-cell-independent immunoglobulin responses by inactivated influenza virus. J Virol 74:4999–5005. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.11.4999-5005.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seubert A, Calabro S, Santini L, Galli B, Genovese A, Valentini S, Aprea S, Colaprico A, D'Oro U, Giuliani MM, Pallaoro M, Pizza M, O'Hagan DT, Wack A, Rappuoli R, De Gregorio E. 2011. Adjuvanticity of the oil-in-water emulsion MF59 is independent of Nlrp3 inflammasome but requires the adaptor protein MyD88. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:11169–11174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107941108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Sahly H. 2010. MF59 as a vaccine adjuvant: a review of safety and immunogenicity. Expert Rev Vaccines 9:1135–1141. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seubert A, Monaci E, Pizza M, O'Hagan DT, Wack A. 2008. The adjuvants aluminum hydroxide and MF59 induce monocyte and granulocyte chemoattractants and enhance monocyte differentiation toward dendritic cells. J Immunol 180:5402–5412. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monaci E, Mancini F, Lofano G, Bacconi M, Tavarini S, Sammicheli C, Arcidiacono L, Giraldi M, Galletti B, Rossi Paccani S, Torre A, Fontana MR, Grandi G, de Gregorio E, Bensi G, Chiarot E, Nuti S, Bagnoli F, Soldaini E, Bertholet S. 2015. MF59- and Al(OH)3-adjuvanted Staphylococcus aureus (4C-Staph) vaccines induce sustained protective humoral and cellular immune responses, with a critical role for effector CD4 T cells at low antibody titers. Front Immunol 6:439. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosca F, Tritto E, Muzzi A, Monaci E, Bagnoli F, Iavarone C, O'Hagan D, Rappuoli R, De Gregorio E. 2008. Molecular and cellular signatures of human vaccine adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:10501–10506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804699105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann K, Castineiras-Vilarino M, Hockendorf U, Hannesschlager N, Lemeer S, Kupka D, Meyermann S, Lech M, Anders HJ, Kuster B, Busch DH, Gewies A, Naumann R, Gross O, Ruland J. 2014. Clec12a is an inhibitory receptor for uric acid crystals that regulates inflammation in response to cell death. Immunity 40:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. 2003. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 425:516–521. doi: 10.1038/nature01991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vesikari T, Forsten A, Herbinger KH, Cioppa GD, Beygo J, Borkowski A, Groth N, Bennati M, von Sonnenburg F. 2012. Safety and immunogenicity of an MF59-adjuvanted A/H5N1 pre-pandemic influenza vaccine in adults and the elderly. Vaccine 30:1388–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young BE, Sadarangani SP, Leo YS. 2015. The avian influenza vaccine Emerflu. Why did it fail? Expert Rev Vaccines 14:1125–1134. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1059760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mestas J, Hughes CC. 2004. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol 172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]