Abstract

The metabolic syndrome has been shown to increase risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study enrolled 15,792 middle-aged Americans in 4 communities in the United States and has followed them for the development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Several analyses from this large, biracial, population study have shown that the metabolic syndrome, as well as individual metabolic syndrome components, is predictive of the prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, carotid artery disease, and diabetes.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, risk factors

Introduction

The metabolic syndrome has been shown to increase risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes and was established as a secondary target of therapy in the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines of the U.S. National Cholesterol Education Program.1 According to the ATP III definition, the metabolic syndrome is diagnosed by the presence of 3 or more of the following characteristics: waist circumference >40 inches (102 cm) in men, >35 inches (88 cm) in women; triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <40 mg/dL in men, <50 mg/dL in women; blood pressure ≥130/≥85 mm Hg; and fasting glucose 110–125 mg/dL.2 Data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate that age-adjusted prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, as defined by the ATP III guidelines, is 27% in adults and has been increasing.3

The role of the metabolic syndrome and its individual components in predicting risk for CVD and diabetes has been examined in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a large, prospective, biracial cohort study of cardiovascular risk factors in 15,792 middle-aged (aged 45–64 years) Americans.4 Analyses have evaluated the influence of the metabolic syndrome on both prevalence and incidence of CVD as well as on the prediction of diabetes.

Metabolic Syndrome and Prevalence of CVD

In a cross-sectional analysis of 14,502 ARIC participants, using data from 1987–1989, prevalence of the metabolic syndrome as defined by ATP III was 30%, with considerable variation across subgroups defined by sex and race.5 The highest metabolic syndrome prevalence was in black women (38%), and the lowest was in black men (26%); 31% of white men and 28% of white women had the metabolic syndrome.

After adjustment for age, ARIC center, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level, and smoking status, ARIC participants who had the metabolic syndrome were 2 times more likely to have prevalent coronary heart disease (CHD; defined as prior myocardial infarction or cardiovascular revascularization) than participants without the metabolic syndrome.5 For each subgroup defined by sex and race, prevalence of CHD (without this adjustment) was significantly higher in individuals with than in individuals without the metabolic syndrome, with the highest CHD prevalence being in white men with the metabolic syndrome (13%, compared with 7% in white men without the metabolic syndrome). Among participants with the metabolic syndrome in other subgroups, CHD prevalence was 11% in black men (compared with 4% in black men without the metabolic syndrome), 4% in black women (compared with 2% in black women without the metabolic syndrome), and 3% in white women (compared with 1% in white women without the metabolic syndrome).

The extent of carotid artery atherosclerosis, assessed by intima–media thickness (IMT) determined by B-mode ultrasound, was also significantly greater in ARIC participants with the metabolic syndrome.5 Mean IMT for 6 segments (carotid bifurcation, common carotid, and internal carotid in left and right carotid arteries) was 747 μm in individuals with and 704 μm in individuals without the metabolic syndrome. After adjustment for age, ARIC center, LDL-C level, smoking status, lipoprotein(a) level, and white blood cell count, IMT in individuals with the metabolic syndrome was 38 μm greater in both white men and white women, 29 μm greater in black women, and 27 μm in black men compared with the corresponding subgroups without the metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic Syndrome and Incidence of CVD

The incidence of CHD and ischemic stroke over a mean 11-year follow-up was also assessed in ARIC participants with and without the metabolic syndrome. In this analysis of data from 12,089 individuals without diabetes, CHD, or stroke at baseline, prevalence of the metabolic syndrome as defined by ATP III was 23%.6 Incident CHD was defined as fatal or nonfatal CHD, silent myocardial infarction identified by electrocardiography, or coronary revascularization. The crude incidence rate of CHD per 10,000 person-years was significantly higher in both men and women with the metabolic syndrome (138.4 and 57.5, respectively) compared with men and women without (92.3 and 22.7, respectively). After adjustment for age, race/ARIC center, LDL-C level, and smoking status, the hazard ratio [HR] for incident CHD in ARIC participants with versus without the metabolic syndrome was 1.46 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23–1.74) in men and 2.05 (95% CI 1.59–2.64) in women (p <0.03 for sex interaction). The metabolic syndrome components most strongly associated with incident CHD were elevated blood pressure and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level. Risk for CHD increased with the number of metabolic syndrome components present; among individuals with 4 or more components present, the HR for incident CHD was 2.23 (95% CI 1.64–3.04) in men and 5.25 (95% CI 3.10–8.89) in women, compared with the respective subgroups with no components of the metabolic syndrome (Figure 1). Applying the lower threshold for impaired fasting glucose (100 mg/dL)7 to the metabolic syndrome did not change the magnitude of observed associations between the metabolic syndrome and either CHD or stroke estimated from the original ATP III definition. In multivariable-adjusted models that included all individual components of the metabolic syndrome, risk for CHD associated with the presence of the metabolic syndrome was not in excess of the risk explained by its individual components. Also, a comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCs) estimated from logistic regression indicated that identification of the metabolic syndrome did not improve CHD risk prediction beyond the Framingham risk score.

Figure 1. Association of coronary heart disease (CHD) risk with metabolic syndrome components in ARIC.

After adjustment for age, race/ARIC center, LDL-C, and smoking status, risk for CHD over 11 years increased with the number of metabolic syndrome components present at baseline.6

The crude incidence rate of ischemic stroke per 10,000 person-years was also significantly higher in ARIC participants with the metabolic syndrome (24.6 in men and 19.0 in women, versus 18.1 and 8.5 in men and women, respectively, without the metabolic syndrome). After adjustment for age, race/ARIC center, LDL-C level, and smoking status, the HR for incident ischemic stroke in ARIC participants with versus without the metabolic syndrome was 1.42 (95% CI 0.96–2.11) in men and 1.96 (95% CI 1.28–3.00) in women.

Metabolic Syndrome and Prediction of Diabetes

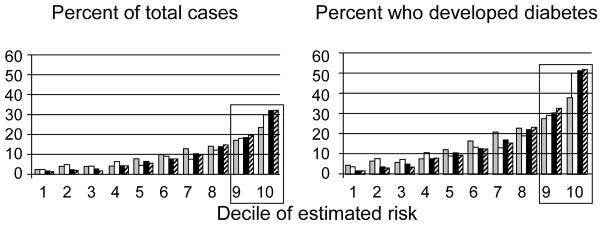

In addition to increasing risk for CVD, the metabolic syndrome increases risk for diabetes. In an analysis of 7,915 ARIC participants without diabetes at baseline, panels of risk factors and presence of the metabolic syndrome were assessed for their predictivity for incident diabetes over 9 years of follow-up.8 For the risk factor panels, models that included fasting glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-C in addition to clinical variables (sex, ethnicity, parental history of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, waist, height; area under the ROC curve [AUC]=0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78–0.82) were significantly better for predicting incident diabetes than clinical variables alone (AUC=0.71, 95% CI 0.69–0.73). However, in a model that assigned 1 point for each criterion of the metabolic syndrome and additional points for obesity and elevated fasting glucose, a score of 3 or more labeled 46% of participants as high risk and identified 81% of future cases of diabetes (AUC=0.78, 95% CI 0.76–0.80). The investigators concluded that rules based on the metabolic syndrome, which may be easier to apply in clinical settings, though slightly less predictive, are valid alternatives to more complex and complete risk function equations.

In a similar investigation evaluating strategies to detect prevalent diabetes not diagnosed by fasting glucose, ARIC investigators evaluated the use of the metabolic syndrome to detect individuals classified as having diabetes by a 2-hour glucose value ≥200 mg/dL during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. The presence of 3 or more ATP III–defined metabolic syndrome abnormalities, while labeling 28% of the sample as positive, identified 40% of individuals with undetected diabetes with a specificity of 72%. By comparison, a clinical prediction rule composed of clinical findings, fasting glucose, HDL-C, and triglycerides, while labeling 30% of the sample as positive, identified 56% of individuals with undetected diabetes with a specificity of 71%.9

Summary

The metabolic syndrome is associated with prevalence and incidence of CHD, stroke, and increased carotid IMT in middle-aged Americans. Although the prediction of incident CHD was not better than with Framingham risk score, most physicians in clinical practice do not use Framingham risk score.10 Furthermore, the metabolic syndrome was also highly predictive for development of diabetes. Thus, the simple clinical criteria of the metabolic syndrome may be helpful in identifying middle-aged individuals with clustered risk factors who may benefit from more intensive lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy accompanied by weight loss to reduce the risk for developing CVD and diabetes.

Figure 2. Predictivity of models for development of incident diabetes in ARIC.

Percent of ARIC participants with incident diabetes by decile of estimated risk (left panel) and percent of individuals in each decile of estimated risk who developed diabetes during 9 years of follow-up (right panel). Models: clinical information (age, race, parental history of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, waist, height), gray bars; fasting glucose, white bars; clinical information plus fasting glucose, black bars; clinical information, fasting glucose, HDL-C, and triglycerides, diagonally striped bars.8

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC-55019, N01-HC-55020, N01-HC-55021, and N01-HC-55022. Additional funding for this study was provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1-DK56918. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

References

- 1.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cholesterol Education Program. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2444–2449. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Heiss G, Golden SH, Duncan BB, East HE, Ballantyne C. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and carotid arterial thickening in patients with the metabolic syndrome (The ARIC Study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Golden SH, Schmidt MI, East HE, Ballantyne CM, Heiss G. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:385–390. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Bang H, Pankow JS, Ballantyne CM, Golden SH, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Identifying individuals at high risk for diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2013–2018. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Vigo A, Pankow J, Ballantyne CM, Couper D, Brancati F, Folsom AR for the ARIC Investigators. Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and other hyperglycemia states: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1338–1343. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Hayes SN, Walsh BW, Fabunmi RP, Kwan J, Mills T, Simpson SL. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111:499–510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]