Abstract

Background

Diagnosing systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) can be extremely challenging if typical arthritis is lacking. A variety of biomarkers have been described for the diagnosis and management of SJIA. However, very few markers have been well-validated. In addition, increasing numbers of biomarkers are identified by high throughput or multi-marker panels.

Method

We identified diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers by systematic literature review, evaluating each according to a predefined level of verification, validation or clinical utility. Diagnostic biomarkers were those identifying SJIA versus (1) non-SJIA conditions or healthy controls (HC) or (2) other non-systemic JIA subtypes. Prognostic biomarkers were those specifically tested for the prediction of (1) disease flare, (2) increased disease activity +/- discrimination of active versus inactive disease, or (3) macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

Results

Fifty-five studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria identifying 68 unique biomarkers, of which 50/68 (74 %) were investigated by only a single research group. Candidate marker verification and clinical utility was evaluated according to whether markers were readily and reliably measurable, investigated by independent study groups, discovered by more than one method (i.e. verified markers) and validated in independent cohorts. This evaluation revealed diagnostic biomarkers of high interest for further evaluation in the diagnostic approach to SJIA that included heme oxygenase-1, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-12, IL-18, osteoprotegerin, S100 calcium-binding protein A12 (S100A12) and S100A8/A9.

Conclusion

In summary, a number of biomarkers were identified, though most had limited evidence for their use. However, our findings combined with the identified studies could inform validation studies, whether in single or multi-marker assays, which are urgently needed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-016-1069-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA), or Still’s disease/syndrome, is a childhood rheumatic condition that is typically characterized by spiking fever in a quotidian pattern, transient rash and arthritis. Patients may alternate between periods of disease activity (flare) and inactive disease. SJIA accounts for around 10–20 % of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), which has an incidence of around 6.6–15 per 100,000 children [1]. Although defined as a subtype of JIA, patients often present with rather unspecific signs and symptoms initially, with the hallmark fever of unknown origin, but without chronic arthritis. Diagnosing SJIA is challenging in these cases as the disease is recognized as an autoinflammatory syndrome rather than classical autoimmune arthritis [2, 3]. Accordingly, most clinical symptoms can be attributed to dysregulated innate immune mechanisms with only minor involvement of adaptive immunity. Gene expression studies of circulating cells show increased levels of transcripts, reflecting monocyte/macrophage-associated activation in SJIA [4–6]. The innate immune cells such as monocytes and macrophages are thought to be drivers of SJIA, producing several mediators implicated in the pathogenesis of SJIA, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 and IL-18 and phagocyte-specific S100 proteins [7]. IL-1 in particular seems to have a prominent role in SJIA. Serum from patients with SJIA induces the transcription of genes of the innate immune system including IL-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Furthermore, activated monocytes from patients with SJIA secrete significantly more IL-1β in comparison with monocytes from healthy controls [6].

Significant challenges to improving the clinical care of patients with SJIA include the discrimination of SJIA from other causes of fever, evidence-based evaluation of response to treatment, detection and limitation of subclinical inflammation and discrimination of SJIA without macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) from SJIA with MAS [8]. MAS is a serious complication of SJIA with a 10 % mortality risk, defined as an acute episode of overwhelming inflammation and characterized by activation and expansion of T lymphocytes and hemophagocytic macrophages. In the early stages, development of MAS is difficult to predict and diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers might enable early intervention.

These challenges could be addressed by the identification and validation of clinically relevant biomarkers, of which those circulating in serum and plasma are useful and easily obtainable from peripheral blood [9–13]. Mechanistic markers are those that are elevated or decreased in response to underlying pathological processes, whereas proxy markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), do not have a definite role in the pathology of the disease, and are non-specific markers of inflammation [14]. Therefore, measurement of a mechanistic biomarker can quantify a pathologic process. With such quantification, a level of severity can be defined, and cutoffs determined, allowing the use of such biomarkers as treatment targets (Fig. 1) [8, 15]. Diagnostic biomarkers, proxy or mechanistic, can aid detection of a disease or confirm it in uncertain cases e.g., evolving SJIA versus sepsis [15, 16].

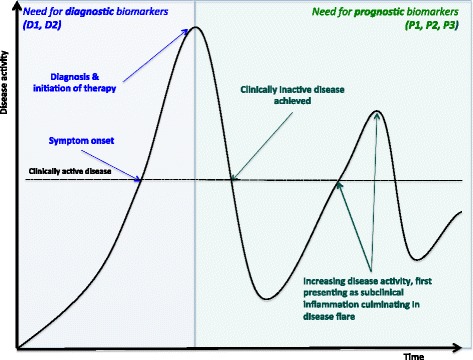

Fig. 1.

Biomarker need in clinical context. Typical clinical sequence in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) from disease onset, diagnosis to clinical resolution and flare. Specific time points where there is a need for diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers are indicated. Diagnostic markers are indicated as follows: D1 SJIA versus other non-JIA conditions, D2 SJIA versus other JIA subtypes. Prognostic markers are indicated as follows: P1 prognostic for flare, P2 prognostic for increased disease activity, P3 prognostic for macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or differentiating MAS from SJIA flare. Adapted from Hinze et al. 2015 [8]

Although a number of publications describe potential biomarkers, none have been recently validated or used in clinical studies aside from the IL-1 family cytokines and the S100-proteins, S100A12 and S100A8/A9 [17]. To date, discovery studies vastly outnumber validation studies, which are more challenging to perform given their requirement for independent cohorts and statistically valid sample sizes. Additionally, the number of identified candidates is usually large and the cost of validation high, leading to a need for unbiased prioritization of candidates for validation [18].

In conclusion, a combination of sensitive biomarkers could allow targeted and personalized treatment and improve treatment outcomes [8]. We therefore identified current candidate diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers from the literature, additionally evaluating their potential for validation/clinical use, function and association with other identified biomarkers. We also discuss the current and future potential of biomarkers for SJIA.

Method

Search criteria

A PubMed search was performed using the search terms as follows: "Arthritis, Juvenile“[Mesh] AND ((”2000/11/01"[PDAT]: “2015/11/01”[PDAT]) AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND English [lang]) along with the additional keywords: 1) cytokine (“cytokines”[MeSH Terms] OR “cytokines”[All Fields] OR “cytokine”[All Fields]) (n = 544 individual studies identified), OR 2) biomarker (“biological markers”[MeSH Terms] OR (“biological”[All Fields] AND “markers”[All Fields]) OR “biological markers”[All Fields] OR “biomarker”[All Fields]) (n = 307), OR 3) validation (n = 114). Abstracts of identified studies were reviewed and any fulfilling exclusion criteria at the outset were excluded, and the full text scrutinized for those remaining.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: studies in which serum or plasma markers were analysed; original research studies; studies that specifically addressed the biomarkers with the diagnostic or prognostic functions as indicated in Table 1 and studies that also included SJIA-specific analyses. Exclusion criteria were: case studies or review articles; studies that included fewer than three patients with SJIA; studies with only negative findings reported (i.e. no statistically significant finding for the candidate marker for the use evaluated) and studies describing functional/cell-based assays or enzyme activity assays. We also excluded studies on adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) [19] and genetic array/genotype or phenotype studies that described individual patients rather than disease signatures, without evaluation of individual biomarkers, even if performed as unbiased discovery studies. Genetic markers and gene expression profiles in SJIA have been previously discussed in a review by Nirmala et al. [20].

Table 1.

Diagnostic and prognostic criteria for inclusion

| Biomarker function | Description | Biomarkers identified (n) | Number of studies in which biomarkers were identified (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | D1: SJIA versus other non-arthritis conditions or HC | 36 | 48 |

| D2: SJIA versus other JIA subtypes | 25 | 25 | |

| Prognostic | P1: for flare (or relapse) | 14 | 16 |

| P2: for increased disease activity and/or the discrimination of active and inactive disease | 15 | 21 | |

| P3: for MAS or discriminating MAS from SJIA flare | 7 | 12 |

Data analysis and categorisation of biomarkers

Details recorded from identified studies included the aims, numbers of included patients and methods of biomarker assessment (Additional file 1). Biomarkers from each study were categorised as diagnostic (discriminating SJIA from non-JIA disorders or healthy controls (HC) termed “D1 biomarkers” or differentiating SJIA from other JIA subtypes, “D2 biomarkers”) or prognostic (for flare, “P1 biomarkers”, increased disease activity or discriminating active versus inactive disease, “P2 biomarkers”, or prognostic for MAS or differentiating SJIA with and without MAS, “P3 biomarkers”), as defined in Table 1, according to the study objectives, and indicated in Fig. 1.

Evaluation of identified markers

Identified candidate biomarkers were scored and ranked by their potential to reach validation or clinical use, with potentially spurious or unreproducible candidate findings ranked the lowest. The biomarker scoring system (BMS) used (Table 2) was developed to identify whether identified candidates (1) were readily measurable, i.e. in standard collected biological samples and without special equipment, (2) had been measured by independent study groups, as confirmation that the biomarker is detectable, (3) had been discovered by more than one method, e.g., proteomic and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods, (4) had been measured by an established assay, i.e. an assay that is well-described, with normal cutoff values available, as this would allow easier translation to clinical practice and finally (5) had been validated for the stated clinical question. Each evaluation question making up the BMS (Table 2) was answered using only the information collected during the review process, and each of the included five questions was scored 0 or 1.

Table 2.

Scoring system used to perform an unbiased evaluation of identified biomarkers

| Q1 | Readily measurable (e.g. in serum) | Yes = 1 | No = 0 |

| Q2 | Measured by more than one independent study group | Yes = 1 | No = 0 |

| Q3 | Discovered by more than one single method | Yes = 1 | No = 0 |

| Q4 | Measured by a reproducible assay | Yes = 1 | No = 0 |

| Q5 | Validated in a validation cohort | Yes = 1 | No = 0 |

| Maximum score = 5, minimum score = 0 |

Results and discussion

Identified candidate biomarkers

A total of 57 studies describing 68 unique biomarkers were identified (Table 3). All reported biomarkers were identified in serum unless otherwise indicated (Additional file 1: Table S1). The mean number of patients with SJIA included in studies was 21 (range 4–60). There were 50 biomarkers (74 %) investigated in studies performed by a single research group and 29/57 studies evaluated a single biomarker. Biomarkers included cytokines, soluble receptors, antibodies, alarmins and other functional molecules (Table 3). The most studied biomarkers were IL-18 (n = 7 individual studies), IL-6 (n = 5), S100A8/A9 (n = 5), S100A12 (n = 4) and soluble CD25 (IL-2 receptor) (n = 4) (Table 3). Only two identified biomarkers, namely S100A8/A9 and S100A12, were described in JIA (but not SJIA) validation studies [21]. Hepcidin, also included as a diagnostic marker, was validated for differentiating SJIA-associated anaemia from anaemia of other causes, but not specifically for SJIA diagnosis [22].

Table 3.

Identified serum and plasma biomarkers

| Biomarker | Detection method | Intended use (P/D) + Reference | BMS scorea Q1 + Q2 + Q3 + Q4 + Q5 = total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation/gene name | Full/alternative name | D | P | ||

| A2M | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| AB-oxLDL | Antibodies to oxidized low-density lipoprotein | Commercial ELISA | [68] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| ACAN | Aggrecan core protein, cartilage-specific core protein | Immunoassay | [69] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| ACPA | Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies | Commercial ELISA | [39] | [39] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| ACT | Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| AECA | Anti-endothelial cell antibodies | In-house ELISA | [70] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| AGP1 | Alpha-1-acid-glycoprotein | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibody | Fluorescence assay | [36] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| Commercial ELISA | [37] | ||||

| Anti-BiP | Anti-immunoglobulin binding protein/glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78) | In-house ELISA | [71] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Anti-CCP | Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide | Commercial ELISA | [72] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| APO A1 | Apolioprotein A1 | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| APO VI | Apolipoprotein VI | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| APRIL | A proliferation-inducing ligand | Commercial ELISA | [73] | [73] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| B2M | Beta -2-microglobulin | Not indicated | [74] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| BAFF | B-cell activating factor | Commercial ELISA | [73] | [73] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| C4 | Complement C4 | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| CCL3 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | Luminex assay | [57] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| CD10 | Cluster of differentiation antigen 10, also called neprilysin | Fluorimetric assay | [75] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| CFH | Complement factor H | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| COMP | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | Commercial ELISA | [39] | [39] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 |

| [76] | [77] | ||||

| [78] | |||||

| CXCL9 | Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 9 | Luminex assay | [57] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Fibrin D-dimer | Commercial assay | [79] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | ||

| FSTL-1 | Follistatin-like protein 1 | Commercial ELISA | [80] | [80] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 |

| [81] | |||||

| GHRL | Ghrelin, appetite regulating hormone | Commercial ELISA | [82] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| GSN | Gelsolin | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Hepcidin | Peptide hormone, released by hepatocytes | Commercial assay | [22] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box protein 1 | Commercial assay | [83] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 | Commercial ELISA | [84] | [85] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 1 = 4 |

| HP | Haptoglobin | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| IFNg | Interferon gamma | Commercial ELISA | [86] | [86] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| IgA RF | Ig A rheumatoid factor isotype | In-house ELISA | [87] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| IgM RF | Ig M rheumatoid factor isotype | In-house ELISA | [87] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 | Commercial ELISA | [88] | [85] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 | Luminex assay | [57] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 | |

| Commercial ELISA | [89] | ||||

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 | Commercial assay Luminex assay | [25] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 | |

| [57] | [24] | ||||

| [86] | [90] | ||||

| [90] | [91] | ||||

| [92] | |||||

| IL-18BP | Interleukin-18 binding protein | Commercial assay | [86] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [90] | [90] | ||||

| IL-1b | Interleukin-1beta | Commercial ELISA | [89] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 | Luminex assay Commercial ELISA | [57] | [24] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 |

| [86] | |||||

| [89] | |||||

| [76] | |||||

| IP-10/CXCL10 | IFNg-induced protein 10, or C-X-C motif chemokine 10 | Commercial ELISA Luminex assay | [57] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [86] | |||||

| [93] | |||||

| LGALS3 | Galectin-3 | Commercial ELISA | [94] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| MIF | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | Luminex assay | [57] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| MMP-3 | Matrix metalloprotinease-3/stromelysin-1 (SL-1) | Commercial ELISA | [72] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Neopterin | Commercial ELISA | [85] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | ||

| NO | Nitric oxide | Spectrophotometry | [95] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin/TNF 11B | Luminex assay Commercial ELISA | [57] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 | |

| [96] | |||||

| OPN | Osteopontin, phosphoglycoprotein | Commercial ELISA | [97] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| RA33 | Anti-heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2 antibodies | Commercial ELISA | [98] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| RANKL | TNF ligand superfamily member 11/receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand | Commercial ELISA | [96] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Resistin | Protein adipokine | Commercial ELISA | [99] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| S100A12 | S100 calcium-binding protein A12 | In-house ELISA Commercial ELISA | [45] | [45] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 |

| [100] | [100] | ||||

| [101] | [102] | ||||

| S100A8/A9 | MRP8/14 (myeloid regulatory protein 8/14) complex, complex of S100A8 (Calgranulin A) and S100A9 (Calgranulin B) | In-house ELISA Commercial ELISA | [23] | 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 0 = 4 | |

| [45] | [23] | ||||

| [101] | [17] | ||||

| [103] | [45] | ||||

| SAA | Serum amyloid A | Commercial ELISA | [45] | [45] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 |

| [76] | |||||

| SAP | Serum amyloid P | Commercial ELISA | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sCD163 | Soluble cluster of differentiation 163/haemoglobin scavenging receptor | Commercial ELISA | [85] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [104] | |||||

| sCD21 | Soluble cluster of differentiation 21 | Commercial ELISA | [105] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sCD23 | Soluble cluster of differentiation 23/soluble low affinity immunoglobulin epsilon Fc receptor) | Commercial ELISA | [105] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sCD25 | Soluble cluster of differentiation 25/soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha | Commercial ELISA | [74] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [104] | |||||

| [106] | |||||

| [107] | |||||

| sE-selectin | Soluble E-selectin adhesion molecule | Commercial ELISA | [108] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [109] | |||||

| [110] | |||||

| sICAM-1 | Soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 | Commercial ELISA | [108] | 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 3 | |

| [109] | |||||

| [110] | |||||

| sRAGE | Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products | Commercial assay | [83] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sST2 | Soluble ST2, also called interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 (IL-1RL1) | Commercial ELISA | [111] | [111] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

| sTM | Soluble thrombomodulin/CD141 | Commercial ELISA | [112] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sTNFR55 | Soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor 55 | Commercial ELISA | [113] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| sTNFR75 | Soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor 75 | Commercial ELISA | [113] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| Survivin | Commercial ELISA | [76] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | ||

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases | Commercial ELISA | [96] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| TNF-alpha | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha | Commercial ELISA | [88] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 | |

| TTR | Transthyretin | Commercial ELISA | [45] | [45] | 1 + 0 + 0 + 1 + 0 = 2 |

aBiomarker scoring system (BMS) biomarker score: each answer is scored as follows: yes = 1, no = 0. D diagnostic, P prognostic, Q1 readily measurable (e.g. in serum), Q2 measured by more than one independent study group, Q3 discovered by more than one single method, Q4 measured by a reproducible assay, Q5 validated in a validation cohort, IFN interferon, TNF tumour necrosis factor

Current clinical uses of identified biomarkers

This study identified some well-established markers of inflammation and/or SJIA, such as the S100-proteins (S100A12 and S100A8/A9 complex), IL-18 and IL-6, autoantibodies, non-specific inflammatory markers and some markers not classically associated with SJIA, such as B cell markers. S100A8/A9 is a predictive biomarker for subclinical disease activity and a predictor of JIA relapse after stopping medication [17, 21, 23]. IL-18 concentration is a known marker of disease activity in SJIA, while IL-18 and IL-6 can define subsets of SJIA [24–26]. While IL-6 and IL-1 are targets of the biological therapies tocilizumab, canakinumab, rilonacept and anakinra, respectively, neither cytokine is routinely measured in patients [27–30]. IL-1b, as already discussed, is usually undetectable in serum and IL-18 is not regularly measured due to technical limitations in performing bioassays [31]; however the reason for IL-6 not being used in routine care is unclear [32, 33].

A number of autoantibodies were identified as candidate biomarkers, including rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA). RF has long been recognised as distinguishing RF-positive and RF-negative forms of polyarthritis (JIA subtypes) [34]. ANA are routinely evaluated in JIA as a screening factor for JIA-associated uveitis [35]. However, Shin et al. showed that ANA levels can change over time in patients with SJIA, which is a finding replicated by Huegle et al. [36, 37] ACPA are associated with joint damage, and are included in the classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis, though they do not have an established use in SJIA [38–40].

CRP and ferritin, which are routinely measured, non-specific, acute phase reactants used as surrogate markers, were described as baseline parameters in most of the identified studies, but were not the subject of investigation in the studies, so were therefore excluded from Tables 1 and 3 and from further analyses. Other non-specific identified biomarkers of inflammation were serum amyloid (SAA), fibrin D-dimer and complement 4 (C4). While previously important in detecting long-term complications of inflammation such as amyloidosis, SAA measurement has become less important since the introduction of biological treatments, which have reduced complications in SJIA.

Candidate biomarkers categorised as diagnostic or prognostic

Some biomarkers were identified in more than one study as described above and evaluated for more than one clinical question (Tables 1 and 3). There were 51 markers characterised as diagnostic, 33 as prognostic and 16 were both diagnostic and prognostic (Table 3): these were ACPA, A proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), B-cell activating factor (BAFF), cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP), follistatin-like protein 1 (FSTL-1), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), interferon gamma (IFNg), IL-10, IL-18, IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP), IL-6, S100A12, S100A8/A9, SAA, soluble ST2/IL-1 receptor-like 1 (sST2) and transthyretin (TTr).

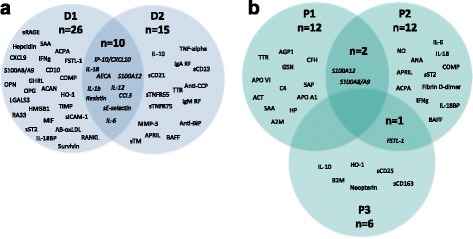

Evaluation of identified markers by clinical question

There were 36 biomarkers that differentiated SJIA from HC or other non-JIA disease (D1 biomarkers) and 25 markers differentiated SJIA from other JIA subtypes (D2 biomarkers). Of the prognostic markers, 14 P1 (flare), 15 P2 (disease activity) and seven P3 (MAS) biomarkers were identified (Table 1). Ten biomarkers were common to D1 and D2 (Fig. 2a); however, few markers overlapped between the prognostic groups (Fig. 2b). This analysis suggests that some biomarkers could have broad use as diagnostic or prognostics markers, rather than being useful only for specific questions. These markers might therefore be more useful than others in a clinical setting, and might therefore be prioritised for validation.

Fig. 2.

Identified biomarkers grouped by clinical question. a Diagnostic biomarkers are shown that differentiated systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) from healthy controls (HC) or other non-JIA disease (D1), SJIA vs other JIA subtypes (D2) or both (D1 and D2). b Prognostic biomarkers for flare (P1), increased disease activity or discriminating active disease from inactive (P2), for macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or discriminating MAS from SJIA flare (P3), or a combination of these are shown. The specific clinical question is very important in interpreting the results of biomarker studies. Little overlap between different diagnostic questions suggests a predominance of different pathways during different stages of disease and therefore a specific hypothesis and clinical question is more useful in studies to understand mechanisms. Biomarkers that are broad enough to cover more than one diagnostic or prognostic category may be more likely to have a specific role in the underlying immunological pathology, and as broad markers will be more useful for wider clinical care. By performing this analysis we can create a shortlist of biomarkers on which to focus. Indeed, only a few markers fall into this group, but perhaps they should receive most attention for future validation in preference to other markers. ACAN aggrecan core protein cartilage-specific core protein, ACCP anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, ACPA anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, ACT alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, AECA anti-endothelial cell antibodies, ANA antinuclear antibodies, Anti-BiP anti-immunoglobulin binding protein/glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78), APO apolioprotein, APRIL A proliferation-inducing ligand, B2M Beta -2-microglobulin, BAFF B-cell activating factor, COMP cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, CRP C-reactive protein, FSTL-1 follistatin-like protein 1, GSN Gelsolin, HO-1 heme oxygenase-1, IFN interferon, IL-18BP IL-18 binding protein, LGAL galectin, MMP matrix metalloproteinase, ONP osteopontin, SAA serum amyloid A, SAP serum amyloid P, sICAM-1 soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1, sST2 soluble ST2/IL-1 receptor-like 1, TIMP tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase, TTr transthyretin

Evaluation of candidate markers

For unbiased and valid results, biomarker evaluation should be performed according to a predefined hypothesis [41] in order to identify candidates more likely to be specific, rather than a high number of unspecific candidates. High throughput methods are increasingly sensitive and producing ever larger numbers of candidate biomarkers; however, they can still be impeded by methodological limitations, such as in LC-MS/MS, by the presence of high abundant proteins [42, 43]. Therefore, careful and evidence-based hypothesis-driven evaluation and prioritisation of candidates for validation studies is vital. While discovery studies are usually unbiased, the prioritisation of identified markers for further evaluation is much more variable, and might be reported as being based on reproducibility, availability of antibodies or levels of protein expression [44]. However, too often these data are omitted, leading to bias in the selection procedure. Ling et al. detected 26 proteins in plasma from patients with SJIA, which differentiated flare from quiescence plasma, of which 18 proteins were significant, and from these the top 15 were selected for unsupervised analysis and shown to remain significant [45]. However, only a limited panel of 9/15 were further tested, chosen according to the availability of antibodies and ELISA. As there is no quantitative and unbiased approach for prioritising candidate markers, we created the novel but unvalidated BMS (Table 2) for this study.

We evaluated each identified biomarker (Table 3) using the BMS (Table 2). No biomarker had the maximum score (5/5). The highest-scoring markers (score 4/5) were HO-1, IL-6, IL-12, IL-18, osteoprotogerin (OPG), S100A12 and S100A8/A9 (n = 7). There were 10 and 51 biomarkers with scores of 3/5 and 2/5, respectively. A score of 3/5 or greater, therefore, identified 17 (25 %) of the total biomarkers. The highest-scoring markers grouped according to diagnostic or prognostic subgroup are indicated in Fig. 1.

Next, the 36 identified D1 biomarkers, the largest group of identified biomarkers for any of the clinical questions asked, were scored and ranked as an example to show how the BMS could prioritise candidates for further evaluation (shown in Fig. 2, scores in Table 3). Seven biomarkers scored 4/5 (as listed above) and seven others scored 3/5, while the remaining 22 markers scored 2/5. This resulted in a panel of 14 markers when the cutoff was applied at a score of 3/5 or above (or n = 15 when S100A8 and S100A9 were analysed as separate proteins). Further ranking of markers within these broad groups was not performed. The online Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) platform was used to identify if any of these 15 proteins had known functions in common [46]. To differing extents STRING identified direct or indirect functional link or interactions between all proteins except S100A12, FSTL-1 and COMP (when tested at the “medium” confidence level). All proteins were identified to be extracellular, consistent with their measurement in peripheral blood, and had an identified immune function role. A summary of the functions of this protein set is shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

The biomarker panel approach

Multiplex cytokine analysis can (1) differentiate SJIA from differential diagnoses and (2) identify distinct profiles in individual patients. Identification of cytokine patterns in individual patients could lead to the identification of subphenotypes within SJIA and also provide insight into the underlying biological basis for the clinical heterogeneity seen in SJIA [47, 48]. This clinical variation and the variety in identified biomarkers supports a prevailing view that a biomarker panel is required [8]. A “multimarker approach” is already used to predict risk of cardiovascular events and the multibiomarker assessment of disease activity (MBDA) is validated for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [49–55]. The MBDA outperforms clinical assessment alone, imaging and single biomarker measurement, and is also cost-effective, measuring 12 biomarkers in just 0.2 ml of serum. A potential panel of biomarkers has recently been identified for paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus, which had good predictive value for detecting the complication lupus nephritis [56]. Jager et al. identified cytokine profiles in paired plasma and synovial fluid samples in 20 patients with SJIA using a bead array based multiplex immunoassay which measured 30 soluble inflammatory mediators in only 50 μl of sample and showed the blind measurement of IL-18 predicted patients with active SJIA with 93 % accuracy [57, 58]. While the identified studies in our analysis often evaluated more than one candidate marker, combinations of markers were not tested and did not feature in study hypotheses/design and/or sample numbers.

Prerequisites for clinical biomarkers

Sample-specific and method-specific factors should be considered before performing either discovery or validation studies [59]. Sample requirements differ according to the planned methodology and platform to be used [60, 61]. Some cytokines, such as IL-1β, are extremely sensitive to degradation by freeze-thawing, whereas IL-18 is comparatively more stable [61]. A clinical biomarker should also fulfil an unmet need and improve existing tests, while also being cost-effective, criteria which will also help define candidates for validation [10, 59, 62]. We did not investigate the cost-effectiveness of markers. However, the validation and clinical use of many of the biomarkers, as described, is limited by the cost and/or local availability of diagnostic tests.

Validation of biomarkers

Most candidate markers (86 %) were identified in a single study and/or by a single group, respectively. While this indicates that multiple groups are working on SJIA biomarkers, each with different strategies, it also reflects a lack of current understanding of the pathology of SJIA. Methods of biomarker verification, as intermediary steps towards validation, become increasingly important as new and improved biomarker discovery techniques result in large numbers of candidates [35, 63]. Identification of the same biomarker by multiple research groups could be seen as a verification step, suggesting a false positive finding to be less likely. Other verification factors might include confirmation that a candidate biomarker can be robustly measurable in peripheral blood, or the use of specific verification methods such as proteomic mass-spectrometry-based selected reaction monitoring (SRM) analysis [18]. SRM measures multiple target proteins, identified from discovery studies or existing literature simultaneously, without requiring specific antibodies as with antibody-based validation techniques, but it does not replace validation.

Biomarker validation, most frequently performed using antibody-based assays, is a difficult, costly and time-consuming process [35]. An example of validation is the included study by Rothmund et al. which compared different assays for measuring S100-proteins in JIA [21, 64]. Biomarker validation, also termed “qualification”, can be separated from clinical validation as a process referring more specifically to the process of linking biomarkers to a clinical endpoint based on evidence and statistical analysis [65]. Validation is widely acknowledged to be a more difficult process than identification, due to the requirement of large numbers of samples of well-defined patients from populations not used in the discovery step. An example use of a validated diagnostic biomarker or panel could allow earlier diagnosis of SJIA, allowing treatment to be started during the “window of opportunity”, the time point early enough in disease that intensive targeted treatment could be used to achieve early disease remission [8, 29, 66]. We therefore focused on identifying potentially clinically relevant diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for SJIA from studies addressing specific clinical questions.

Conclusions

There remains a need for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple biomarkers and an unbiased method of selecting candidate biomarkers for further evaluation. The parallel use of different methodological platforms such as microbead arrays (e.g. Luminex xMAP), aptamer-based assay or label-free liquid mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) could improve the spectrum of detected proteins [67], while the BMS used here is an example of how candidate markers could be prioritised. Markers that exclude SJIA would also be useful in the clinical setting. In particular, markers diagnostic for the main differential diagnoses of SJIA, such as the causes of fever of unknown origin, which might include infection or malignancy, would help exclude SJIA as a diagnosis. While this review was not designed to explore markers of differential diagnoses of SJIA, including them in a potential multi-marker panel would likely improve such a diagnostic assay.

Sixty-eight unique candidate markers evaluated for the management of SJIA were identified by this literature review. Only one identified study was a validation study and very few identified biomarkers were evaluated by more than one study group. Therefore, there is a clear and urgent need to confirm and consolidate findings from discovery studies and validate findings. The use of emerging technologies, with collaborative efforts, may ultimately help achieve the goal of validating new diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers, or panels of biomarkers, for improving the management of SJIA.

Abbreviations

ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; APRIL, A proliferation-inducing ligand; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; BMS, biomarker scoring system; COMP, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein; CRP, C-reactive protein; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; FSTL-1, follistatin-like protein 1; HC, healthy controls; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IL-18BP, IL-18 binding protein; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (non-systemic); LC-MS/MS, label-free liquid mass spectrometry; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; MBDA, multibiomarker assessment of disease activity; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; RF, rheumatoid factor; SAA, serum amyloid A; SJIA, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; SRM, selected reaction monitoring; sST2, soluble ST2/IL-1 receptor-like 1; STRING, search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins platform; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TTr, transthyretin

Acknowledgements

For assistance in accessing the literature, we thank Aisha Gohar (University Hospital Centre, Utrecht), Patrick Maschmeyer (German Rheumatism Centre, Berlin) and Bechara Mfarrej (San Rafaelle Hospital, Milan).

Funding

FG was supported by the EU FP7 EUTRAIN (European Translational Training for Autoimmunity & Immune manipulation Network) project grant (ref.289903). FG, ML and DF received funding from the EU FP7 MIAMI project grant, ref- 305266 (Monitoring innate Immunity in Arthritis and Mucosal Inflammation).

Availability of supporting data

All data were sourced from published work, as referenced in the manuscript. A summary of each paper evaluated in this review is provided in Additional file 1: Table S1 and STRING analysis is summarised in Additional file 2 Table S2.

Authors’ contributions

FG conceived the study and performed the literature review and analysis. DF, CK, ML and DH participated in the study design and analyses. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript and all made substantial contributions to the content and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

FG is a paediatric trainee and a PhD candidate and Marie Curie Fellow in the European Union FP7-funded EUTRAIN Programme (European Translational Training for Autoimmunity & Immune Manipulation Network) at the Department of Paediatric Rheumatology and Immunology, University Children's Hospital Münster, Germany. Previously she worked as an academic clinical fellow at the University of Liverpool, Alder Hey Children’s National Health Service Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK. Currently, she is investigating serum biomarkers for autoinflammatory disorders. CK graduated in Biosciences and obtained a PhD on antibody-peptide interaction studies from Goethe-University Frankfurt, Germany. In 2009, he joined Rikard Holmdahl at Medical Inflammation Research, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden for postdoctoral training in developing peptide-based tools for the diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Following his interest in innate immune functions in inflammation, he joined DF’s team at the Department of Paediatric Rheumatology and Immunology in 2012. There he leads a clinical-translational junior research group focusing on mechanistic aspects of alarmin signalling and innate and adaptive immune functions in arthritis. ML graduated in Microbiology and later, by studying the response of the avian innate immunity against bacterial and viral respiratory pathogens, gained his PhD in Biological and Biotechnical Sciences - Genetics at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. As a Marie Curie TRACKS (Transglutaminases: role in pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy) postdoctoral fellow in the group of Roberto Marzari at Life Science Department, University of Trieste, Italy, he studied the transglutaminase 2 (TG2) interactome and the interaction between TG2 and celiac disease auto-antibodies. Joining DF’s team in 2012, his current research interests as a senior postdoctoral researcher in the EU FP7-funded MIAMI (Monitoring innate immunity in arthritis and mucosal inflammation) project are serum biomarkers in autoinflammatory diseases, like JIA and IBD, and the mechanisms of pathogenesis and the immune response in Kawasaki and celiac disease. DH graduated in Medicine and started his residency in Paediatrics at the University of Münster, Germany in 2007. In 2008, he joined Johannes Roth as Research Associate at the Institute of Immunology, Münster, where he studied S100 proteins as biomarkers and damage-associated molecular patterns in autoinflammatory diseases, and the role of the innate immune response during S. aureus infection. In 2013, he joined DF at the Department of Paediatric Rheumatology and Immunology, University Children’s Hospital Münster, Germany where he continues his research on autoinflammatory diseases, and is training as a paediatric rheumatologist. DF is a full professor and head of paediatric rheumatology and immunology at the University of Münster, Germany. His research focus is on clinical–translational science with an overall objective to translate the knowledge from basic science on innate immunity into tools to improve the stratification of patients, with regard to their disease characteristics and prognostic factors. He coordinates major national and international research consortia and has an active role not only in the German Society of Paediatric Rheumatology but also in international networks such as the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS). He was awarded several prizes and co-organizes major international symposia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Each author has consented to the publication of this work.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No patients were involved in the study.

Additional files

Full summary of included studies. (DOCX 153 kb)

Functional enrichments identified by STRING analysis for the top scoring 15 proteins which differentiated SJIA from non-arthritis conditions or healthy controls. (DOCX 15 kb)

Contributor Information

Faekah Gohar, Email: Faekah.Gohar@ukmuenster.de.

Christoph Kessel, Email: Christoph.Kessel@ukmuenster.de.

Miha Lavric, Email: Miha.Lavric@ukmuenster.de.

Dirk Holzinger, Email: Dirk.Holzinger@ukmuenster.de.

Dirk Foell, Phone: +49 251 8358178, Email: dfoell@uni-muenster.de.

References

- 1.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, He X, Maldonado-Cocco J, Orozco-Alcala J, Prieur A, Suarez-Almazor ME, Woo P; International League of Associations for Rheumatology. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31;390–92. http://www.jrheum.org/content/31/2/390.citation. [PubMed]

- 2.Martini A. It is time to rethink juvenile idiopathic arthritis classification and nomenclature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(9):1437–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattorno M, Piccini A, Lasigliè D, Tassi S, Brisca G, Carta S, et al. The pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1505–15. doi: 10.1002/art.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fall N, Barnes M, Thornton S, Luyrink L, Olson J, Ilowite NT, et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood from patients with untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis reveals molecular heterogeneity that may predict macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3793–804. doi: 10.1002/art.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macaubas C, Nguyen KD, Peck A, Buckingham J, Deshpande C, Wong E, et al. Alternative activation in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis monocytes. Clin Immunol. 2012;142(3):362–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, Punaro M, Banchereau J. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1479–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellins ED, Macaubas C, Grom AA. Pathogenesis of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: some answers, more questions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(7):416–26. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinze C, Gohar F, Foell D. Management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: hitting the target. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(5):290–300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Grisar J, Redlich K, Steiner G, Wagner O. The need for prognosticators in rheumatoid arthritis. Biological and clinical markers: where are we now? Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(3):208. doi: 10.1186/ar2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tektonidou MG, Ward MM. Validation of new biomarkers in systemic autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;12:708–17. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessel C, Holzinger D, Foell D. Phagocyte-derived S100 proteins in autoinflammation: putative role in pathogenesis and usefulness as biomarkers. Clin Immunol. 2013;147(3):229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duurland CL, Wedderburn LR. Current developments in the use of biomarkers for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(3):406. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0406-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consolaro A, Varnier GC, Martini A, Ravelli A. Advances in biomarkers for paediatric rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(5):265–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Robinson WH, Lindstrom TM, Cheung RK, Sokolove J. Mechanistic biomarkers for clinical decision making in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(5):267–76. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldenhuis CNAM, Oosting SF, Gietema JA, de Vries EGE. Prognostic versus predictive value of biomarkers in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(7):946–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Søreide K. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic, prognostic and predictive biomarker research. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(1):1–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzinger D, Frosch M, Kastrup A, Prince FHM, Otten MH, Van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, et al. The Toll-like receptor 4 agonist MRP8/14 protein complex is a sensitive indicator for disease activity and predicts relapses in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):974–80. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau TYK, Power KA, Dijon S, Gardelle I De, Mcdonnell S, Duffy MJ, et al. Prioritization of candidate protein biomarkers from an in vitro model system of breast tumor progression toward clinical verification research articles. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(3):1450–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bae CB, Suh CH, An JM, Jung JY, Jeon JY, Nam JY, et al. Serum S100A12 may be a useful biomarker of disease activity in adult-onset still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(12):2403–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nirmala N, Grom A, Gram H. Biomarkers in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a comparison with biomarkers in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(5):543–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Rothmund F, Gerss J, Ruperto N, Däbritz J, Wittkowski H, Frosch M, et al. Validation of relapse risk biomarkers for routine use in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;66(6):949–55. doi: 10.1002/acr.22248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cangemi G, Pistorio A, Miano M, Gattorno M, Acquila M, Bicocchi MP, et al. Diagnostic potential of hepcidin testing in pediatrics. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(4):323–30. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foell D, Wulffraat N, Wedderburn LR, Wittkowski H, Frosch M, Gerss J, et al. Methotrexate withdrawal at 6 vs 12 months in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(13):1266–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lotito APN, Campa A, Silva CAA, Kiss MHB, Mello SBV. Interleukin 18 as a marker of disease activity and severity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(4):823–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jelusić M, Lukić IK, Tambić-Bukovac L, Dubravcić K, Malcić I, Rudan I, et al. Interleukin-18 as a mediator of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(8):1332–4. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu M, Nakagishi Y, Yachie A. Distinct subsets of patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis based on their cytokine profiles. Cytokine. 2013;61(2):345–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Kenwright A, Wright S, Calvo I, et al. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2385–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Patel P, Palucka AK, Chaussabel D, Banchereau J. How the study of children with rheumatic diseases identified interferon-alpha and interleukin-1 as novel therapeutic targets. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:39–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vastert SJ, de Jager W, Noordman BJ, Holzinger D, Kuis W, Prakken BJ, et al. Effectiveness of first-line treatment with recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in steroid-naive patients with new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2014;66(4):1034–43. doi: 10.1002/art.38296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P, Constantin T, Wulffraat N, Horneff G, et al. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2396–406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterfield L, Whiteside T. Cytokine Assays. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaines Das RE, Poole S. The international standard for interleukin-6. J Immunol Methods. 1993;160(2):147–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledur A, Fitting C, David B, Hamberger C, Cavaillon J-M. Variable estimates of cytokine levels produced by commercial ELISA kits: results using international cytokine standards. J Immunol Methods. 1995;186(2):171–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00184-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor P, Gartemann J, Hsieh J, Creeden J. A systematic review of serum biomarkers anti-cyclic citrullinated Peptide and rheumatoid factor as tests for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmune Dis. 2011;2011:815038. doi: 10.4061/2011/815038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson DS, Rooney ME, Finnegan S, Qiu J, Thompson DC, Labaer J, et al. Biomarkers in rheumatology, now and in the future. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(3):423–33. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hügle B, Hinze C, Lainka E, Fischer N, Haas J-P. Development of positive antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis points toward an autoimmune phenotype later in the disease course. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin JI, Kim KH, Chun JK, Lee TJ, Kim KJ, Kim HS, et al. Prevalence and patterns of anti-nuclear antibodies in Korean children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis according to ILAR criteria. Scand J Rheumatol. Informa UK Ltd UK. 2008;37(5):348–51. doi: 10.1080/03009740801998762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–81. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilliam BE, Chauhan AK, Low JM, Moore TL. Pediatric rheumatology. Measurement of biomarkers in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients and their significant association with disease severity: a comparative study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(3):492–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berntson L, Nordal E, Fasth A, Aalto K, Herlin T, Nielsen S, et al. Anti-type II collagen antibodies, anti-CCP, IgA RF and IgM RF are associated with joint damage, assessed eight years after onset of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings J, Raynaud F, Jones L, Sugar R, Dive C. Fit-for-purpose biomarker method validation for application in clinical trials of anticancer drugs. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(9):1313–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swan AL, Stekel DJ, Hodgman C, Allaway D, Alqahtani MH, Mobasheri A, et al. A machine learning heuristic to identify biologically relevant and minimal biomarker panels from omics data. BMC Genomics. 2015;16 Suppl 1:S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson NGL, Anderson NGL. The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1(11):845–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R200007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solé X, Crous-Bou M, Cordero D, Olivares D, Guinó E, Sanz-Pamplona R, et al. Discovery and validation of new potential biomarkers for early detection of colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ling XB, Park JL, Carroll T, Nguyen KD, Lau K, Macaubas C, et al. Plasma profiles in active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Biomarkers and biological implications. Proteomics. 2010;10(24):4415–30. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.STRING: functional protein association networks [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jan 7]. Available from: http://string-db.org/. Accessed 27 July 2016.

- 47.van den Ham H-J, de Jager W, Bijlsma JWJ, Prakken BJ, de Boer RJ, Van Den Ham H, et al. Differential cytokine profiles in juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes revealed by cluster analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(8):899–905. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eng SWM, Duong TT, Rosenberg AM, Morris Q, Yeung RSM. The biologic basis of clinical heterogeneity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 2014;66(12):3463–75. doi: 10.1002/art.38875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang TJ, Gona P, Larson MG, Tofler GH, Levy D, Newton-Cheh Ch, et al. Multiple biomarkers for the prediction of first major cardiovascular events and death. N Eng J Med. 2006;355(25):2631–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Eastman PS, Manning WC, Qureshi F, Haney D, Cavet G, Alexander C, et al. Characterization of a multiplex, 12-biomarker test for rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2012;70:415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curtis JR, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Knevel R, Huizinga TW, Haney DJ, Shen Y, et al. Validation of a novel multibiomarker test to assess rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(12):1794–803. doi: 10.1002/acr.21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centola M, Cavet G, Shen Y, Ramanujan S, Knowlton N, Swan KA, et al. Development of a multi-biomarker disease activity test for rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bakker MF, Cavet G, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JWJ, Haney DJ, Shen Y, et al. Performance of a multi-biomarker score measuring rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in the CAMERA tight control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(10):1692–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michaud K, Strand V, Shadick NA, Degtiar I, Ford K, Michalopoulos SN, et al. Outcomes and costs of incorporating a multibiomarker disease activity test in the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(9):1640–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Segurado OG, Sasso EH. Vectra DA for the objective measurement of disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(Suppl. 85):S29–S34. [PubMed]

- 56.Smith E, Oni L, Midgley A, Ekdawy D, Corkhill R, Jones C, et al. Demonstration of an “excellent” biomarker panel for identifying active lupus nephritis in children. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;331.

- 57.de Jager W, Hoppenreijs EPAH, Wulffraat NM, Wedderburn LR, Kuis W, Prakken BJ. Blood and synovial fluid cytokine signatures in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):589–98. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.061853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Jager W, Velthuis H, Prakken BJ, Rijkers GT, Kuis W. Simultaneous detection of 15 human cytokines in a single sample of stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells simultaneous detection of 15 human cytokines in a single sample of stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10(1):133–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.1.133-139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sturgeon C, Hill R, Hortin GL, Thompson D. Taking a new biomarker into routine use–a perspective from the routine clinical biochemistry laboratory. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2010;4(12):892–903. doi: 10.1002/prca.201000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gillio-Meina C, Cepinskas G, Cecchini EL, Fraser DD. Translational research in pediatrics II: blood collection, processing, shipping, and storage. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):754–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Jager W, Bourcier K, Rijkers GT, Prakken BJ, Seyfert-Margolis V. Prerequisites for cytokine measurements in clinical trials with multiplex immunoassays. BMC Immunol. 2009;10(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van den Bruel A, Cleemput I, Aertgeerts B, Ramaekers D, Buntinx F. The evaluation of diagnostic tests: evidence on technical and diagnostic accuracy, impact on patient outcome and cost-effectiveness is needed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gibson DS, Finnegan S, Pennington S, Qiu J, LaBaer J, Rooney ME, Duncan MW. Chapter 8: Validation of Protein Biomarkers to Advance the Management of Autoimmune Disorders. In: Huang F-P, editor. Autoimmune Disorders - Current Concepts and Advances from Bedside to Mechanistic Insights. InTech; 2011. p. 614. ISBN 978-953-307-653-9. doi:10.5772/1851.

- 64.Hunter DJ, Losina E, Guermazi A, Burstein D, Lassere MN, Kraus V. A pathway and approach to biomarker validation and qualification for osteoarthritis clinical trials. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11(5):536–45. doi: 10.2174/138945010791011947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JW, Devanarayan V, Barrett YC, Weiner R, Allinson J, Fountain S, et al. Fit-for-purpose method development and validation for successful biomarker measurement. Pharm Res. 2006;23(2):312–28. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nigrovic PA. Review: is there a window of opportunity for treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis? Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 2014;66(6):1405–13. doi: 10.1002/art.38615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McArdle A, Butt AQ, Szentpetery A, Jager W De, Roock S de, FitzGerald O, et al. Technical brief. Developing clinically relevant biomarkers in inflammatory arthritis: a multi-platform approach for serum candidate protein discovery. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2015;1–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Simonini G, Matucci Cerinic M, Cimaz R, Anichini M, Cesaretti S, Zoppi M, et al. Evidence for immune activation against oxidized lipoproteins in inactive phases of juvenile chronic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Sayed ZA, Saleh MT, Al-Wakkad AS, Sherief LS, AM N e-D. Cartilage proteoglycan aggrecan as a predictor of joint damage in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7(6):992–1003. [PubMed]

- 70.Bloom BJ, Toyoda M, Petrosian A, Jordan S. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies are prevalent in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: implications for clinical disease course and pathogenesis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27(7):655–60. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bodman-Smith MD, Fife MF, Wythe H, Corrigal VM, Panayi GS, Wedderburn LR, et al. Anti-BiP antibody levels in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(10):1305–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ozawa R, Inaba Y, Mori M, Hara R, Kikuchi M, Higuchi R, et al. Definitive differences in laboratory and radiological characteristics between two subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: systemic arthritis and polyarthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22(4):558–64. doi: 10.3109/s10165-011-0540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gheita TA, Bassyouni IH, Emad Y, el-Din AMN, Abdel-Rasheed E, Hussein H. Elevated BAFF (BLyS) and APRIL in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients: relation to clinical manifestations and disease activity. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(3):285–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kounami S, Yoshiyama M, Nakayama K, Okuda M, Okuda S, Aoyagi N, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in children with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. Acta Haematol. 2005;113(2):124–9. doi: 10.1159/000083450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simonini G, Azzari C, Gelli AMG, Giani T, Calabri GB, Leoncini G, et al. Neprilysin levels in plasma and synovial fluid of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25(5):336–40. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Galeotti L, Adrian K, Berg S, Tarkowski A, Bokarewa M, Silvia Q. Pediatric rheumatology. Circulating survivin indicates severe course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(2):373–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakajima S, Naruto T, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, Mori M, Nishimaki S, et al. Improvement of reduced serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients treated with the anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(1):42–6. doi: 10.3109/s10165-008-0115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Urakami T, Manki A, Inoue T, Oda M, Tanaka H, Morishima T. Clinical significance of decreased serum concentration of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(5):996–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bloom BJ, Alario AJ, Miller LC. Persistent elevation of fibrin D-dimer predicts long term outcome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):422–6. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.070600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilson DC, Marinov AD, Blair HC, Bushnell DS, Thompson SD, Chaly Y, et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 is a mesenchyme-derived inflammatory protein and may represent a biomarker for systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2510–6. doi: 10.1002/art.27485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gorelik M, Fall N, Altaye M, Barnes MG, Thompson SD, Grom AA, et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 and the ferritin/erythrocyte sedimentation rate ratio are potential biomarkers for dysregulated gene expression and macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(7):1191–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi T, Trachana M, Agakidis C, Pratsidou-Gertsi P, Taparkou A, Lampoudi S, et al. Ghrelin levels in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: relation to anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment and disease activity. Metabolism. 2011;60(10):1359–62. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bobek D, Grčević D, Kovačić N, Lukić IK, Jelušić M. The presence of high mobility group box-1 and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products in juvenile idiopathic arthritis and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takahashi A, Mori M, Naruto T, Nakajima S, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, et al. The role of heme oxygenase-1 in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(3):302–8. doi: 10.3109/s10165-009-0152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shimizu M, Yachie A. Compensated inflammation in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: role of alternatively activated macrophages. Cytokine. 2012;60(1):226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Put K, Avau A, Brisse E, Mitera T, Put S, Proost P, et al. Cytokines in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: tipping the balance between interleukin-18 and interferon-γ. Rheumatology. 2015;54(8):1507–17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ferreira RA, Silva CHM, Silva DAO, Sopelete MC, Kiss MHB, Mineo JR, et al. Is measurement of IgM and IgA rheumatoid factors (RF) in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis clinically useful? Rheumatol Int. 2007;27(4):345–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shahin AA, Shaker OG, Kamal N, Hafez HA, Gaber W, Shahin HA. Circulating interleukin-6, soluble interleukin-2 receptors, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-10 levels in juvenile chronic arthritis: correlations with soft tissue vascularity assessed by power Doppler sonography. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22(2):84–8. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yilmaz M, Kendirli SG, Altintas D, Bingöl G, Antmen B. Cytokine levels in serum of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20(1):30–5. doi: 10.1007/s100670170100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen O, Shan N, Zhu X, Wang Y, Ren P, Wei D, et al. The imbalance of IL-18/IL-18BP in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin Shanghai. 2013;45(4):339–41. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shimizu M, Yokoyama T, Yamada K, Kaneda H, Wada H, Wada T, et al. Distinct cytokine profiles of systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome with particular emphasis on the role of interleukin-18 in its pathogenesis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(9):1645–53. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maeno N, Takei S, Nomura Y, Imanaka H, Hokonohara M, Miyata K. Highly elevated serum levels of interleukin-18 in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis but not in other juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes or in Kawasaki disease: comment on the article by Kawashima et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2539–41. doi: 10.1002/art.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aggarwal A, Agarwal S, Misra R. Chemokine and chemokine receptor analysis reveals elevated interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP)-10/CXCL10 levels and increased number of CCR5+ and CXCR3+ CD4 T cells in synovial fluid of patients with enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148(3):515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ezzat MHM, El-Gammasy TMA, Shaheen KYA, Osman AOY. Elevated production of galectin-3 is correlated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis disease activity, severity, and progression. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14(4):345–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bica BERG, Gomes NM, Fernandes PD, Luiz RR, Koatz VLG. Nitric oxide levels and the severity of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27(9):819–25. doi: 10.1007/s00296-007-0321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sarma PK, Misra R, Aggarwal A. Elevated serum receptor activator of NFkappaB ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin (OPG), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)3, and ProMMP1 in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(3):289–94. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Masi L, Ricci L, Zulian F, Del Monte F, Simonini G, Capannini S, et al. Serum osteopontin as a predictive marker of responsiveness to methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(10):2308–13. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tomoum HY, Mostafa GA, El-Shahat EMF. Autoantibody to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-A2 (RA33) in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinical significance. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(2):188–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gheita TA, El-Gazzar II, El Shazly RI, El-Din AMN, Abdel-Rasheed E, Bassyouni RH. Elevated serum resistin in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: relation to categories and disease activity. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(1):297–301. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Foell D, Wittkowski H, Hammerschmidt I, Wulffraat N, Schmeling H, Frosch M, et al. Monitoring neutrophil activation in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis by S100A12 serum concentrations. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1286–95. doi: 10.1002/art.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shenoi S, Ou J-N, Ni C, Macaubas C, Gersuk VH, Wallace CA, et al. Comparison of biomarkers for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Res. International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. 2015;78(5):554–9. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wittkowski H, Frosch M, Wulffraat N, Goldbach-Mansky R, Kallinich T, Kuemmerle-Deschner J, et al. S100A12 is a novel molecular marker differentiating systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other causes of fever of unknown origin. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3924–31. doi: 10.1002/art.24137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Frosch M, Ahlmann M, Vogl T, Wittkowski H, Wulffraat N, Foell D, et al. The myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 complex, a novel ligand of toll-like receptor 4, and interleukin-1beta form a positive feedback mechanism in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):883–91. doi: 10.1002/art.24349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bleesing J, Prada A, Siegel DM, Villanueva J, Olson J, Ilowite NT, et al. The diagnostic significance of soluble CD163 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain in macrophage activation syndrome and untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):965–71. doi: 10.1002/art.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Singh A, Vastert SJ, Prakken BJ, Illges H. Decreased levels of sCD21 and sCD23 in blood of patients with systemic-juvenile arthritis, polyarticular-juvenile arthritis, and pauciarticular-juvenile arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(6):1581–7. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lehmberg K, Pink I, Eulenburg C, Beutel K, Maul-Pavicic A, Janka G. Differentiating macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other forms of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2013;162(6):1245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reddy VV, Myles A, Cheekatla SS, Singh S, Aggarwal A. Soluble CD25 in serum: a potential marker for subclinical macrophage activation syndrome in patients with active systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(3):261–7. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen C, Tsao C, Ou L, Yang M, Kuo M, Huang J. Comparison of soluble adhesion molecules in juvenile idopathic arthritis between the active and remission stages. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:167–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Benedetti F, Vivarelli M, Pignatti P, Oliveri M, Massa M, Pistorio A, et al. Circulating levels of soluble E-selectin, P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(9):2246–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bloom BJ, Nelson SM, Eisenberg D, Alario AJ. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and E-selectin as markers of disease activity and endothelial activation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(2):366–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ishikawa S, Shimizu M, Ueno K, Sugimoto N, Yachie A. Soluble ST2 as a marker of disease activity in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Cytokine. 2013;62(2):272–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.El-Gamal YM, Heshmat NM, El-Kerdany TH, Fawzy AF. Serum thrombomodulin in systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15(3):270–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2004.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Muzaffer MA, Dayer J-M, Feldman BM, Pruzanski W, Roux-Lombard P, Schneider R, et al. Differences in the profiles of circulating levels of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist reflect the heterogeneity of the subgroups of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(5):1071–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]