Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Depressive symptoms and disability each increase the risk of the other, yet few studies have examined reciprocal associations between these conditions in a single study, or over periods longer than 3 years. These associations may differ in older caregivers due to chronic stress, health characteristics, or factors related to caregiving.

Design and Methods:

Structural equation models were used to investigate relationships between depressive symptoms and disability over 3 interviews spanning 6 years among 956 older women (M = 81.5 years) from the Caregiver Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Results were evaluated separately for 611 noncaregivers and 345 caregivers to a relative or friend.

Results:

In noncaregivers, more depressive symptoms significantly predicted greater disability, whereas greater disability predicted increased depressive symptoms at the next interview in age-adjusted models. In contrast, there was not a significant relationship between depression and disability in either direction for caregivers. Further adjustment for body mass index and medical condition variables did not change these relationships.

Implications:

Caregivers did not exhibit longitudinal or reciprocal relationships between depressive symptoms and disability observed in noncaregivers. It is possible that older women caregivers are buffered by better physical condition or social interactions related to caregiving activities.

Keywords: Caregiving, Depression, Disability, Activities of daily living

Depression and disability are two of the most common health conditions in older adults and are highly associated with each other (Blazer & Hybels, 2005; Noh & Posthuma, 1990; Prince, Harwood, Thomas, & Mann, 1998; Turner & Noh, 1988). Prospective studies have found that persons with more depressive symptoms have an increased risk of subsequent disability (Armenian, Pratt, Gallo, & Eaton, 1998; Ormel et al., 1993). In addition, older individuals with more depressive symptoms also experience worse physical functioning (Bruce, Seeman, Merrill, & Blazer, 1994; Prince et al., 1998). However, most studies focus on the influence of either psychological distress or disability on the other as an outcome, not reciprocal relationships between these conditions over time. Of the longitudinal studies that attempted to disentangle reciprocal relationships (Aneshensel, Frerichs, & Huba, 1984; Chen et al., 2012; Gayman, Turner, & Cui, 2008; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011; Ormel, Rijsdijk, Sullivan, van Sonderen, & Kempen, 2002), only a few followed nondisabled older samples for more than 3 years (Chen et al., 2012; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011). Examination of these study results suggests that a follow-up period of greater than 3 years may be required for a reciprocal pattern to develop.

Further, none of the studies of older community-dwelling adults has considered the influence of major activities on the relationship between disability and depressive symptoms. For example, many older adults engage in caregiving activities that may affect psychological and physical well-being (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). Although other major life activities such as working or recreational activities might be considered, those activities (e.g., volunteering or leisure-time physical activity) may be more determined by a person’s health capabilities and socioeconomic and neighborhood characteristics than caregiving is. Yet caregiving occurs in most families at some point. Caregiving actions have been characterized as goal-directed, purposeful activities (Corcoran, 2011); this view aligns well with the definition of “caregiver” used in the current study.

Although one study examined how receiving informal care influenced the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability (Lin & Wu, 2011), to our knowledge, no study has examined whether being a caregiver modifies this relationship. Given that an estimated 52 million adults are currently informal caregivers to adult relatives or friends (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2012), understanding the impact of caregiving on the relationship between disability and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling adults is critical. The current study evaluated the longitudinal and reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms and disability over 6 years, and whether these associations differed in caregivers and noncaregivers from a large, multisite sample of community-dwelling older women.

Depressive Symptoms and Disability

Findings from prospective studies suggest that reciprocal relationships should be observed between depressive symptoms and disability when assessed over multiple time points, that is, depressive symptoms influence disability at a subsequent time point and vice versa. Several mechanisms may produce this reinforcing effect. If depression produces a listlessness and reduces an individual’s desire for action (“I could not get going” [Radloff, 1977]), with time this inactivity itself may lead to an increased feeling of restriction or ill-health. This may be especially true in older people, who may also experience health decline and disability with age; as this decline often affects multiple systems (Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994), it may limit an individual’s routine and desired activities, possibly leading to depression (Prince et al., 1998). Medications taken for health conditions may also affect psychological well-being, also producing depression. Through these mechanisms, a reinforcing cycle of depression and disability may be established.

Disability is often measured by the number of limitations in basic and/or instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs/IADLs; Chen et al., 2012; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011) or variations on that definition (Aneshensel et al., 1984; Gayman et al., 2008; Ormel et al., 2002). However, longitudinal studies have shown mixed results: Reciprocal relationships between depressive symptoms and disability were found in studies with follow-up periods of 7–10 years (Chen et al., 2012; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011) but generally not in those with shorter follow-up periods spanning 1–3 years (Aneshensel et al., 1984; Gayman et al., 2008; Ormel et al., 2002). Rather, these shorter studies found that depressive symptoms led to increased disability over time, but disability had no impact on depressive symptoms (Aneshensel et al., 1984; Ormel et al., 2002) or that disability influenced subsequent depressive symptoms but not vice versa (Gayman et al., 2008). Reciprocal relationships were also more likely to be observed in healthy older community-dwelling adults (Chen et al., 2012; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011) than in middle-aged adults with some disability (Gayman et al., 2008) or older adults who had serious physical limitations (Ormel et al., 2002) or were receiving informal care (Lin & Wu, 2011).

The finding that health status modified the association between depressive symptoms and disability suggests that this association may differ in older caregivers and noncaregivers, yet the nature of these differences is not obvious. Caregivers consistently report more depression than noncaregivers (Adams, 2008; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003): The toll of chronic stress and depression may increase caregivers’ vulnerability to the effects of depressive symptoms and disability on each other. Conversely, some caregivers have better physical functioning (Fredman, Doros, Ensrud, Hochberg, & Cauley, 2009; Herrera et al., 2013) and cognitive functioning (Bertrand et al., 2012; Herrera et al., 2013) than noncaregivers, suggesting that caregivers may be less susceptible to the downstream effects of depressive symptoms and disability. Information about the role of caregiving on the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and disability would expand our knowledge about this association and have potential public health implications.

Theoretical Models of the Impact of Caregiving on Depressive Symptoms and Disability

Two theoretical models provide frameworks for how longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms and disability may differ for caregivers and noncaregivers. The Caregiver Stress Process Model (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) postulates that a caregiver’s socioeconomic characteristics, caregiving context and experience, and personal and social resources join to form a process that influences the caregiver’s mental and physical health. By their very nature, caregivers’ experiences would differ from those of noncaregivers (Pearlin et al., 1990). Based on this model and theories of stress and health, caregivers would be expected to have more depressive symptoms and worse physical functioning, as well as stronger longitudinal interrelationships between these conditions, than noncaregivers. However, although studies on psychological well-being support this model, studies of physical health outcomes are mixed (Brown et al., 2009; Fredman et al., 2009; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). These inconsistent results may be due to methodological limitations or to comparing noncaregivers to caregivers with the most demanding caregiving loads. For example, dementia caregivers are typically more stressed than other caregivers (Ory, Hoffman, Yee, Tennstedt, & Schulz, 1999).

The Healthy Caregiver Hypothesis offers an alternative framework for the observation of better health outcomes in caregivers. This model proposes that older adults who are healthier and more physically active become caregivers and remain as caregivers and therefore would have better health outcomes than noncaregivers (Bertrand et al., 2012; Fredman, Cauley, Hochberg, Ensrud, & Doros, 2010). Further, caregivers may experience improved physical and cognitive health outcomes due to maintaining fitness to help a care recipient or to health benefits derived directly from the satisfaction of giving support (Bertrand et al., 2012). In fact, caregivers had better physical and cognitive functioning than noncaregivers in samples of older women (Bertrand et al., 2012) and older Mexican Americans (Herrera et al., 2013). Moreover, those who performed more caregiving activities experienced lower mortality rates (Brown et al., 2009) and less decline in physical functioning (Fredman et al., 2009) than other caregivers and noncaregivers. Thus, the Healthy Caregiver Hypothesis model would predict that, regardless of their level of depressive symptoms, caregivers would have better physical functioning than noncaregivers and that the associations between depressive symptoms and disability would be weaker in caregivers than noncaregivers.

The current study used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine relationships between depressive symptoms and disability at three interviews covering approximately 6 years, using ADL/IADL limitations as a measure of disability. To explore the contrasting models presented by these two theoretical frameworks, analyses were performed separately in caregiver and noncaregiver participants from the Caregiver Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF). As our study follow-up is greater than 3 years, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms and disability would show reciprocal longitudinal relationships such that depressive symptoms would influence subsequent disability, and greater disability would influence subsequent depressive symptoms. Because of the evidence for better physical functioning in older caregivers, we hypothesized that these associations would be weaker in caregivers than noncaregivers.

Data and Methods

Caregiver SOF Sample

The sample used for this analysis was derived from Caregiver SOF, an ancillary study to SOF (Cummings et al., 1990). SOF included 9,704 women aged 65 and older who were recruited between 1986 and 1988 from four areas in the United States: Baltimore County, MD; Minneapolis, MN; Portland, OR; and the Monongahela Valley, PA. Women were excluded if they were unable to walk without help or had a history of bilateral hip replacement. African American women were initially excluded because of their low incidence of hip fracture, but in 1997, a cohort of 662 African American women with functional characteristics similar to the baseline SOF sample was added. Approximately every 2 years, SOF participants receive a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

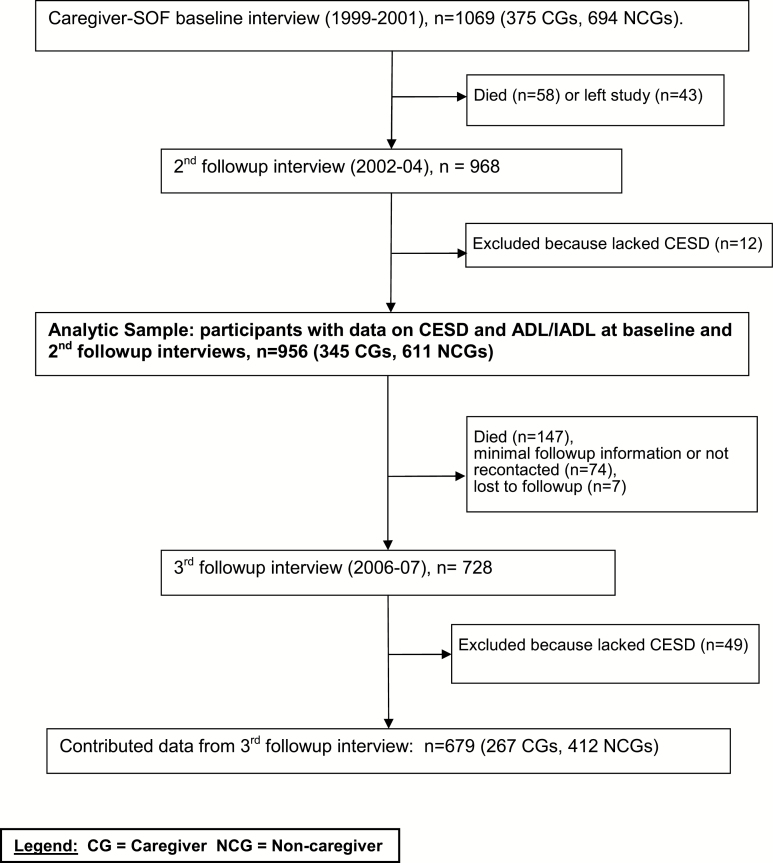

Participants in Caregiver SOF included members of the original and African American SOF cohorts who participated in the sixth biennial SOF examination that took place between 1997 and 1999 (Figure 1). The Caregiver SOF sample was identified in two phases, described elsewhere (Fredman, Doros, Cauley, Hillier, & Hochberg, 2010; Fredman et al., 2004). The first phase consisted of administering a caregiver screening questionnaire to 5,952 SOF participants who had their sixth biennial examination at their home or a SOF clinic and were not cognitively impaired or living in a long-term care facility. The second phase began in 1999 and consisted of readministering the screening questionnaire by telephone to all caregivers and a subset of noncaregivers who had been identified by the initial screening questionnaire. The questionnaire asked SOF participants whether they currently helped a relative or friend with each of seven IADL tasks (use the telephone, get to places out of walking distance, shop, prepare meals, manage medications, manage finances, do heavy housework; Pfeiffer, 1978) and seven ADL tasks (walk across a room, groom, transfer from bed to chair, eat, dress, bathe, use the toilet; Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963) because physical, cognitive, or psychological impairment prevented that person from performing the task independently. These measures have excellent validity (Katz et al., 1963; Pfeiffer, 1978). Participants were categorized as caregivers if they helped one or more persons with at least one task and as noncaregivers if they did not help anyone with these tasks.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the analytic sample within the Caregiver Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Notes: CG = caregiver; NCG = noncaregiver.

In the telephone reevaluation phase, respondents who were currently caregiving were invited to participate in the Caregiver SOF. Respondents who had stopped caregiving (n = 493) were excluded. After each caregiver agreed to participate, a group of one to five SOF participants was randomly selected from those identified as noncaregivers by the screening questionnaire and who matched the caregiver on age, race, SOF site, and zip code. The first one or two noncaregivers from each group who agreed to participate were included, resulting in a sample of 375 caregivers and 694 noncaregivers.

Within 2 weeks of the telephone reevaluation, a face-to-face interview was conducted with respondents at their homes (Caregiver SOF baseline interview). Follow-up contact included quarterly post cards and biennial examinations for the parent SOF and additional Caregiver SOF interviews. Including the baseline interview, four face-to-face Caregiver SOF interviews took place between 1999 and 2007. The first three interviews were conducted annually, whereas the fourth was conducted an average of 3.8 years after the third.

The institutional review boards at each SOF site and at the Boston University Medical Center approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Analytic Sample

The data for this analysis came from three Caregiver SOF interviews: the baseline interview (1999–2002); the second annual follow-up interview (2002–2004); and the third follow-up interview (2006–2007). These interviews were chosen to maximize the number of participants over the longest possible time period while maintaining a similar number of years between each time point. The sample was restricted to 956 participants who had data on both depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations at the baseline and the second annual follow-up interviews.

Measurements

Primary Variables

Depressive Symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale was used to measure depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). Respondents indicated how frequently they experienced each item in the past week on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from rarely or none of the time (0) to almost or all of the time (3). Possible CES-D scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms.

Disability

At each interview, respondents reported their ability to independently perform seven ADL and seven IADL tasks (Katz et al., 1963; Pfeiffer, 1978). For each question, a dichotomous variable was created based on the respondent’s indication of whether she could do the task without help (0) versus needing some help or being completely unable to do the task (1). We created a measure based on the sum of ADL and IADL limitations: Possible scores range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater disability.

Stratification Variable

Caregiver Status

Using baseline interview data, participants were classified as caregivers or noncaregivers based on whether they helped someone with at least one ADL or IADL task at the baseline interview, as described above. For sensitivity analyses, we used a more stringent definition: classifying as caregivers those who helped someone with two or more ADLs or six or more IADL tasks, which was the cut point we used to distinguish high- and low-intensity caregivers in previous analyses (Fredman et al., 2009).

Other Characteristics

Other variables from the Caregiver SOF baseline interview used to describe the participants included: age, body mass index (BMI) calculated from height at the sixth SOF biennial exam and weight taken in the baseline Caregiver SOF interview, a count of self-reported medical conditions (arthritis, emphysema/respiratory illness, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease), self-reported race (white or African American), and marital status (married or not married).

Statistical Analyses

We compared characteristics of caregivers and noncaregivers at baseline using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We then used the Mplus statistical package (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011) to fit structural equation path models to examine relationships between depressive symptoms and disability across the three interviews. A missing data indicator was specified in each model. Mplus uses all available data to estimate the model using maximum likelihood methods with robust standard errors, without data imputation. Depressive symptoms and disability were each represented by a continuous score. For each model tested, we fit the model with all possible pathways from one time period to next so that the action of any component was assumed to flow through the following time period. In other words, no paths from the baseline interview to the third follow-up interview were specified in the model. Unstandardized beta coefficients with standard errors were generated to describe associations between variables. Model fit was measured by the comparative fit index and root mean square error of approximation (Kline, 2011).

In each stage of modeling, caregiver status was used as a grouping factor to ensure identical structural equation path models were run on caregivers and noncaregivers. Age at each interview was included as a continuous covariate in all models. To explore whether caregiver status modified the associations between depressive symptoms and disability, we compared overall model fit between a fully constrained model (all path coefficients constrained to be the same in the caregivers and noncaregiver groups) and a partially constrained model (paths from disability to depressive symptoms or vice versa were allowed to differ between the two groups). The primary model examined the associations between depressive symptoms (CES-D score) and disability (ADL/IADL limitations) in separate groups of noncaregivers and caregivers from the full sample of 956 participants.

One methodological concern with our primary analysis is that depressive symptoms and disability both follow skewed distributions with many subjects at the floor value of these scales. To address this concern, we performed secondary analyses treating these variables as left-censored. Fitting these models through Mplus requires using Monte Carlo integration that prohibits the calculation of measures of model fit, and so these are presented as secondary models.

Additional secondary analyses evaluated potential confounding by baseline BMI and a count of medical conditions, two covariates used in other research (Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005). Another variation of the primary model used the natural log of the CES-D score rather than the raw score to determine whether skewness in the raw CES-D score affected results.

Additional secondary analyses altered the analysis sample to explore the robustness of our findings. First, we used multiple imputation methods to include data for women who withdrew, were lost to follow-up, or were excluded from the primary analyses because of missing data. Regression methods were used to impute missing data on variables in the primary analysis from these variables (via PROC MI in SAS). Ten imputed data sets were created, and results of SEM analyses were combined across the imputed data sets using multiple imputation methods in Mplus. A second analysis limited the sample to participants with data at all three time points (n = 679); a third analysis used our analytic sample of 956 women but employed a more stringent definition of caregiving to classify noncaregivers and caregivers (caregivers helped with two or more ADLs or six or more IADLs).

Results

Participant Characteristics

The baseline Caregiver SOF sample included 1,069 women, of whom 884 (83%) were followed through the third follow-up interview or death. One hundred thirteen women were excluded from these analyses because they had died (n = 58), withdrawn from SOF or Caregiver SOF (n = 43), or lacked data on depressive symptoms (n = 12) at the second follow-up interview. Compared with the 956 women included in these analyses, those who were excluded were significantly older, had lower BMI, and reported more medical conditions, ADL/IADL limitations, and depressive symptoms. There were no significant differences in race, marital status, or education.

Of the 956 women with data at baseline and the second follow-up interview, 728 (76%) had third follow-up interviews. As is typical of long-term studies among older adults, the main reason why women lacked a follow-up interview was death (147 women); another 74 were not recontacted (30 due to budget constraints at one study site) or provided minimal follow-up information, and seven were lost to follow-up. Of the 728 who were interviewed, 48 lacked complete data on the CES-D, and 1 participant lacked data on both CES-D and ADLs/IADLs, resulting in 679 women available for these analyses at the third follow-up interview. Those without data at all three interviews were significantly older at baseline, had lower BMI, and more medical conditions and ADL/IADL limitations. They had similar depression scores to those included in the sample at baseline but were significantly more depressed at the second follow-up visit. They were not significantly different in race, marital status, or education.

Based on their baseline interview status, a total of 345 participants were classified as caregivers, and 611 were classified as noncaregivers (see Table 1); this grouping was preserved through analyses (i.e., caregiver status was not time varying). Noncaregivers were slightly older than caregivers (mean age 81.7 vs 81.3 years, p = .06). Caregivers were significantly more likely than noncaregivers to be married and college educated and had significantly fewer ADL and IADL limitations at each interview but did not differ on baseline BMI, number of medical conditions, race, or CES-D scores. Over the three interviews, both groups experienced an increase in depressive symptoms and disability.

Table 1.

Comparison of Noncaregivers and Caregivers in Caregiver SOF

| Full Sample (n = 956) | Noncaregivers (n = 611) | Caregivers (n = 345) | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age at baseline: mean (SD) | 81.6 (3.6) | 81.7 (3.7) | 81.3 (3.5) | .06 |

| BMI at baseline: mean (SD) | 27.5 (5.2) | 27.5 (5.3) | 27.4 (5.1) | .71 |

| Medical conditions at baselineb | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.1) | .91 |

| Race: % white | 87.9% | 88.1% | 87.5% | .81 |

| Marital status at baseline: % married | 37.5% | 27.3% | 55.4% | <.01 |

| Education at baseline: % college or more | 46.2% | 51.6% | 57.7% | .07 |

| ADL/IADL sum at baseline | 1.0 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.7) | 0.7 (1.1) | <.01 |

| ADL/IADL sum at second follow-up | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.9 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.1) | <.01 |

| ADL/IADL sum at third follow-up | 2.8 (3.4), n = 727 | 3.1 (3.6), n = 451 | 2.3 (3.0), n = 276 | <.01 |

| CES-D at baseline | 7.3 (6.6) | 7.1 (6.3) | 7.8 (7.0) | .11 |

| CES-D at second follow-up | 8.1 (6.6) | 7.8 (6.2) | 8.5 (7.1) | .12 |

| CES-D at third follow-up | 8.7 (7.0), n = 679 | 8.6 (7.1), n = 412 | 8.7 (6.9), n = 267 | .82 |

Notes: ADL/IADL = activities of daily living/instrumental activities of daily living; BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale; SOF = Study of Osteoporotic Fractures.

a p value is for comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers.

bSum of nine medical conditions: arthritis, emphysema/respiratory illness, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease.

Characteristics Associated With Depressive Symptoms and Disability in Noncaregivers and Caregivers

Among noncaregivers, those who were non-white, less educated, unmarried, and had more medical conditions had significantly more depressive symptoms. Baseline age and BMI were not associated with depressive symptoms. Similar relationships were observed in caregivers, except there was no association by race, and married caregivers had higher levels of depressive symptoms than unmarried caregivers (results not shown).

Older age, higher BMI, lower education, and a greater number of medical conditions were associated with greater disability among noncaregivers, whereas race and marital status were not. Similar associations were observed for caregivers, except there was no significant association for education (results not shown)

Preliminary Analyses

To explore effect modification by caregiver status, we compared model fit between a fully constrained model (χ2 = 127.965, 32 df) and a partially constrained model (χ2 = 119.222, 28 df), which allowed paths between depressive symptoms and disability to vary by caregiver status. This comparison gave a borderline statistically significant difference between the models (p = .07), supporting our decision to stratify by caregiver status.

Associations Between Depressive Symptoms and Disability

Noncaregivers

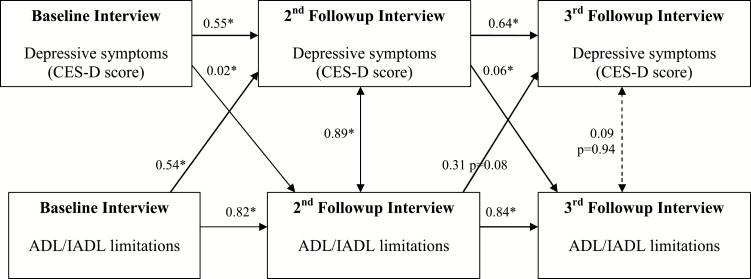

Among noncaregivers, our primary model found statistically significant longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms and disability from baseline to the second annual follow-up interview (Figure 2). Higher depressive symptoms predicted greater disability at the following interview (beta = 0.02, p < .05), and greater baseline disability also predicted higher depressive symptoms at the following interview (beta = 0.54, p < .05). Similar associations were seen between the second and third annual follow-up interviews.

Figure 2.

Depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations. Noncaregivers only (n = 611). Notes: *Significant at p < .05 unless otherwise noted. All values shown are unstandardized coefficients. Model RMSEA = 0.091, 90% CI [0.074, 0.109], CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.956. No path constraints. Grouping used to separately evaluate noncaregivers and caregivers. Correlation between depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations at baseline = 0.26. Covariance values shown in the diagram at the second and third follow-up interviews (0.89 and 0.15, respectively) are generated as part of the model. Relationships with age are not shown in the diagram. Age at second follow-up with depressive symptoms at second follow-up, β = 0.07, p = .21. Age at second follow-up with ADL/IADL limitations at second follow-up, β = 0.11, p < .01. Age at third follow-up with depressive symptoms at third follow-up, β = 0.05, p = .62. Age at third follow-up with ADL/IADL limitations at third follow-up, β = 0.17, p < .01. ADL/IADL = activities of daily living/instrumental activities of daily living; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index.

Furthermore, depressive symptoms at one interview were strong predictors of subsequent depressive symptoms (e.g., beta = 0.55, p < .05, relating depressive symptoms at baseline to the second follow-up interview), and similarly disability strongly predicted subsequent disability (e.g., beta = 0.82, p < .05, relating disability at baseline to the second follow-up interview).

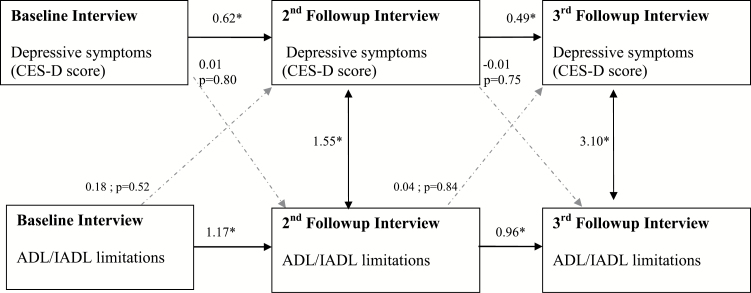

Caregivers

In contrast to noncaregivers, depressive symptoms and disability were not significantly associated over time among caregivers (Figure 3, beta = 0.01, p = .80, relating depressive symptoms at baseline to disability at the second follow-up interview). Similar to the noncaregivers, depressive symptoms at one interview were strong predictors of subsequent depressive symptoms (e.g., beta = 0.62, p < .05, relating depressive symptoms at baseline to the second follow-up interview), whereas disability strongly predicted subsequent disability (beta = 1.17, p < .05, relating disability at baseline to the second follow-up interview).

Figure 3.

Depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations. Caregivers only (n = 345). Notes: *Significant at p < .05 unless otherwise noted. All values shown are unstandardized coefficients. Model RMSEA = 0.091, 90% CI [0.074, 0.109], CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.956. No path constraints. Grouping used to separately evaluate noncaregivers and caregivers. Correlation between depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations at baseline = 0.20. Covariance values shown in the diagram at the second and third follow-up interviews (1.55 and 3.10, respectively) are generated as part of the model. Relationships with age are not shown in the diagram. Age at second follow-up with depressive symptoms at second follow-up, β = 0.13, p = .14. Age at second follow-up with ADL/IADL limitations at second follow-up, β = 0.09, p < .01. Age at third follow-up with depressive symptoms at third follow-up, β = −0.02, p = .85. Age at third follow-up with ADL/IADL limitations at third follow-up, β = 0.12, p = .01. ADL/IADL = activities of daily living/instrumental activities of daily living; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index.

Additional Analyses

In the covariate model, there was no evidence for confounding by BMI or medical conditions in caregivers or noncaregivers, when evaluated by change in estimate of the main effects.

Secondary analyses modeling depressive symptoms and disability as censored variables support the results of the primary analysis, giving identical results in terms of significant and nonsignificant pathways. Likewise, the variation in the primary model using the natural log of the CES-D did not improve associations and made it more difficult to interpret the estimates (results not shown).

Multiple imputation analyses gave similar results as the primary analysis (results not shown). All statements of significance (at p < .05) from these analyses agreed with the primary model (Figures 2 and 3) with one exception: For caregivers, the significance of the covariance between the CES-D and ADL/IADL limitations at the third follow-up interview was reduced to p = .055.

Limiting the sample to participants with data at all three time points (noncaregiver n = 412; caregiver n = 267) resulted in some weakening of associations but the overall results were similar (results not shown). The sensitivity analysis with a more stringent definition of caregiving (noncaregivers n = 782; caregivers n = 174) gave essentially the same results as our primary model, except for one difference among noncaregivers for disability at the second follow-up predicting depressive symptoms at the third follow-up: The beta coefficient was smaller and not quite significant (current primary model beta = 0.403, p = .026; sensitivity model beta = 0.261, p = .114). Because the sample of noncaregivers for this model included some of the original caregivers with fewer ADL/IADLs, this is not unexpected. There were no notable differences for the caregiver results (although the betas for highly nonsignificant paths can be quite different).

None of the model variations explained differences between caregivers and noncaregivers seen in the primary model.

Discussion

This study found that depressive symptoms and disability formed reciprocal longitudinal relationships in older women noncaregivers, but not caregivers followed for 6 years. These results in noncaregivers replicate previous studies of community-dwelling older adults followed for 6 or more years (Chen et al., 2012; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Lin & Wu, 2011) although reciprocal associations disappeared after controlling for covariates in one study (Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005). Moreover, previous studies included both men and women, and some characteristics differed by gender (i.e., women may have been more depressed than men), yet none found that the main associations differed significantly by gender.

Other studies using similar SEM analysis methods did not observe reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations in middle- and older-aged adults. The lack of reciprocal associations may have been due to shorter follow-up periods (Aneshensel et al., 1984; Gayman et al., 2008; Ormel et al., 2002) or samples specifically selected for increased disability (Gayman et al., 2008; Ormel et al., 2002).

In contrast, we did not observe this reinforcing cycle between depression and disability among caregivers. Consistent with the Healthy Caregiver Hypothesis, depressive symptoms did not lead to greater disability in caregivers. Caregivers had more depressive symptoms than noncaregivers at each interview but also fewer ADL/IADL limitations than noncaregivers at all three interviews. These results run counter to the Caregiver Stress Process Model that would have predicted that greater depressive symptoms would lead to greater disability in the caregivers.

These differing results may be explained by additional factors experienced by caregivers but not noncaregivers. The Caregiver Stress Process Model postulates mediators (coping and social support) that may buffer the effects of stress between psychological and physical outcomes (Pearlin et al., 1990). Although we lacked information on these factors, compared with noncaregivers, caregivers may have had more interaction with others and may have received more social support from family members or health care providers; this sense of engagement may have helped to disrupt a cycle between depressive symptoms and disability. Studies suggest that social engagement is associated with a slower increase in depressive symptoms (Glass, Mendes De Leon, Bassuk, & Berkman, 2006), whereas maintenance of a depressive mood is influenced more by levels of social support and participation than by disability (Prince et al., 1998). Perceived support may help buffer the effects of disability and depression (Yang, 2006). By providing instrumental or emotional care to others, particularly a spouse, caregivers may have prevented or delayed a decline in their own health (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003; Brown et al., 2009; Poulin et al., 2010) or helped to maintain their physical functioning (Fredman et al., 2009). Further, studies examining the sociocultural context of different caregiving styles (Corcoran, 2011) describe caregivers as engaging in goal-directed, purposeful activities. These activities may enhance the meaning in one’s life and distract from minor health decline, even if the individual is depressed, preventing a self-reinforcing cycle of decline and depression from becoming established.

The different associations in noncaregivers and caregivers may result from greater disability or poorer health status among noncaregivers than caregivers; evidence indicates remaining disabled can lead to increasing depressive symptoms (Yang & George, 2005). However, caregivers and noncaregivers were not significantly different in baseline age, BMI, or health status, and neither BMI nor medical conditions affected these associations in either noncaregivers or caregivers. Alternatively, noncaregivers may have been more likely to receive informal help with ADL/IADL limitations than caregivers. One study (Lin & Wu, 2011) that found reciprocal effects between depressive symptoms and disability, also found a persistent deleterious health effect in those receiving informal care.

This study had several limitations. The Caregiver SOF sample was comprised of older women who were mainly white, possibly limiting generalizability to younger or non-white women or to men. The majority of caregivers in the United States are older white women so this is unlikely to be an issue for caregivers (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2012). We grouped participants according to baseline caregiver status and continued that status throughout the follow-up period. Although this approach ignores possible changes in caregiver status over the follow-up period, it is conceptually and analytically straightforward and is used in most studies examining health effects of caregiving (Adams, 2008; Brown et al., 2009; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). We lacked the ability to control for potential confounders such as social support.

Nonetheless, this study had a number of strengths. The SEM approach allowed the evaluation of multiple associations simultaneously in a single model: that is, the longitudinal and reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms and disability and the associations across multiple intervals instead of a single interval. The longitudinal data included three interviews over approximately 6 years. The mean time between the second and third annual follow-up interviews was nearly twice as long as between the baseline and second follow-up interviews, yet the reciprocal relationships seen among the noncaregivers remained statistically significant, illustrating the enduring effects of depression and disability on each other over this time period. The Caregiver SOF sample was also a strength in that all caregivers and noncaregivers came from the same base population, minimizing potential bias that might have been introduced had we selected noncaregivers from one source (e.g., a community sample) and caregivers from another (e.g., a registry). Inclusion criteria for caregivers at baseline required that they were performing at least one ADL or IADL task for a recipient. This created a heterogeneous group of caregivers, including not only spouse caregivers but also other family and nonfamily relationships, giving a wide generalizability to older female caregivers.

Finally, we obtained basically the same results using multiple imputation analyses as our primary analyses, suggesting that missing data did not bias the results. Multiple imputation methods require that data are missing at random. The 30 participants who were not recontacted due to budget constraints were likely missing completely at random. If the chance of missing data also depended on current depression or ADL/IADL limitations, after controlling for the imputed variables, then data would not be missing at random.

Our study found longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between depressive symptoms and ADL/IADL limitations among older female noncaregivers but not in the caregivers. Although caregiving is often associated with increased stress, depression, and physical demands, the goal-directed and helping context in which caregiving occurs may forestall ADL/IADL decline. Future research should explore how helping behaviors, stress-coping styles, a sense of social engagement, or performing purposeful activities may mediate or modify associations between depressive symptoms and disability. In conclusion, our results underscore the need for practitioners and researchers to separate the aspects of caregiving that have adverse health consequences from those that are beneficial (Brown et al., 2003, 2009; Poulin et al., 2010) and to promote those beneficial aspects among all older adults.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG18037, R01 AG005407, R01 AR35582, R01 AR35583, R01 AR35584, R01 AG005394, R01 AG027574, and R01 AG027576).

References

- Adams K. B. (2008). Specific effects of caring for a spouse with dementia: Differences in depressive symptoms between caregiver and non-caregiver spouses. International Psychogeriatrics, 20, 508–520. doi:10.1017/S1041610207006278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel C. S., Frerichs R. R., Huba G. J. (1984). Depression and physical illness: A multiwave, nonrecursive causal model. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, 350–371. doi:10.2307/2136376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenian H. K. Pratt L. A. Gallo J., & Eaton W. W (1998). Psychopathology as a predictor of disability: A population-based follow-up study in Baltimore, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology, 148, 269–275. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand R. M., Saczynski J. S., Mezzacappa C., Hulse M., Ensrud K., Fredman L. (2012). Caregiving and cognitive function in older women: Evidence for the healthy caregiver hypothesis. Journal of Aging and Health, 24, 48–66. doi:10.1177/0898264311421367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G., & Hybels C. F (2005). Origins of depression in later life. Psychological Medicine, 35, 1241–1252. doi:10.1017/S0033291705004411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., Nesse R. M., Vinokur A. D., Smith D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320–327. doi:10.1111/1467–9280.14461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L. Smith D. M. Schulz R. Kabeto M. U. Ubel P. A. Poulin M. … Langa K. M (2009). Caregiving behavior is associated with decreased mortality risk. Psychological Science, 20, 488–494. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02323.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. L., Seeman T. E., Merrill S. S., Blazer D. G. (1994). The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 1796–1799. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.11.1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. M., Mullan J., Su Y. Y., Griffiths D., Kreis I. A., Chiu H. C. (2012). The longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and disability for older adults: A population-based study. The Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67, 1059–1067. doi:10.1093/gerona/gls074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M. A. (2011). Caregiving styles: A cognitive and behavioral typology associated with dementia family caregiving. The Gerontologist, 51, 463–472. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings S. R. Black D. M. Nevitt M. C. Browner W. S. Cauley J. A. Genant H. K. … Vogt T. M (1990). Appendicular bone density and age predict hip fracture in women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. JAMA, 263, 665–668. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440050059033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving. (2012). Fact sheet: Selected caregiver statistics. Retrieved from https://caregiver.org/selected-caregiver-statistics [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L., Cauley J. A., Hochberg M., Ensrud K. E., Doros G. (2010). Mortality associated with caregiving, general stress, and caregiving-related stress in elderly women: Results of caregiver-study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58, 937–943. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02808.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L., Doros G., Cauley J. A., Hillier T. A., Hochberg M. C. (2010). Caregiving, metabolic syndrome indicators, and 1-year decline in walking speed: Results of Caregiver-SOF. The Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65, 565–572. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L., Doros G., Ensrud K. E., Hochberg M. C., Cauley J. A. (2009). Caregiving intensity and change in physical functioning over a 2-year period: Results of the caregiver-study of osteoporotic fractures. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 203–210. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L. Tennstedt S. Smyth K. A. Kasper J. D. Miller B. Fritsch T. … Harris E. L (2004). Pragmatic and internal validity issues in sampling in caregiver studies: A comparison of population-based, registry-based, and ancillary studies. Journal of Aging and Health, 16, 175–203. doi:10.1177/0898264303262639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayman M. D., Turner R. J., Cui M. (2008). Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: Exploring the nature of the association. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, S219–S228. doi:10.1093/geronb/63.4.S219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass T. A., Mendes De Leon C. F., Bassuk S. S., Berkman L. F. (2006). Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Aging and Health, 18, 604–628. doi:10.1177/0898264306291017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera A. P., Mendez-Luck C. A., Crist J. D., Smith M. L., Warre R., Ory M. G., Markides K. (2013). Psychosocial and cognitive health differences by caregiver status among older Mexican Americans. Community Mental Health Journal, 49, 61–72. doi:10.1007/s10597-012-9494-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S., ford A. B., moskowitz R. W., jackson B. A., jaffe M. W. (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA, 185, 914–919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore J. A., Ferraro K. F. (2005). A 3-D model of health decline: Disease, disability, and depression among Black and White older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 376–391. doi:10.1177/002214650504600405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin I. F., Wu H. S. (2011). Does informal care attenuate the cycle of ADL/IADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life? The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 585–594. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., & Muthén B. O (1998. –2011). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S., & Posthuma B (1990). Physical disability and depression: A methodological consideration. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 9–15. doi:10.1177/000841749005700104 [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., Rijsdijk F. V., Sullivan M., van Sonderen E., Kempen G. I. (2002). Temporal and reciprocal relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, P338–P347. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.4.P338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., Von Korff M., Van den Brink W., Katon W., Brilman E., Oldehinkel T. (1993). Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 385–390. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.3.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Hoffman R. R., III, Yee J. L., Tennstedt S., Schulz R. (1999). Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. The Gerontologist, 39, 177–185. doi:10.1093/geront/39.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Mullan J. T., Semple S. J., Skaff M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. (1978). Multidimensional functional assessment: The OARS methodology (2nd ed.). Durham, NC: Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sörensen S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18, 250–267. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin M. J., Brown S. L., Ubel P. A., Smith D. M., Jankovic A., Langa K. M. (2010). Does a helping hand mean a heavy heart? Helping behavior and well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychology and Aging, 25, 108–117. doi:10.1037/a0018064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. J., Harwood R. H., Thomas A., Mann A. H. (1998). A prospective population-based cohort study of the effects of disablement and social milieu on the onset and maintenance of late-life depression. The Gospel Oak Project VII. Psychological Medicine, 28, 337–350. doi:10.1017/S0033291797006478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J., Noh S. (1988). Physical disability and depression: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 29, 23–37. doi:10.2307/2137178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M., Jette A. M. (1994). The disablement process. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 38, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. (2006). How does functional disability affect depressive symptoms in late life? The role of perceived social support and psychological resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 355–372. doi:10.1177/002214650604700404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., George L. K. (2005). Functional disability, disability transitions, and depressive symptoms in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 17, 263–292. doi:10.1177/0898264305276295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]