Abstract

A 5-year-old, spayed female Weimaraner dog was evaluated for progressive left forelimb lameness localized to the carpus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to arrive at a presumptive diagnosis of intermedioradial carpal (IRC) bone fracture with avascular necrosis (AVN). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of naturally occurring AVN of the canine IRC diagnosed using MRI.

Résumé

Diagnostic non invasif, à l’aide d’imagerie par résonnance magnétique, d’une nécrose avasculaire présumée de l’os intermédioradial du carpe chez le chien. Une chienne Weimaraner stérilisée âgée de 5 ans a été évaluée pour une boiterie progressive de la patte avant gauche située au carpe. L’imagerie par résonance magnétique (IRM) a été utilisée pour parvenir à un diagnostic présomptif d’une fracture de l’os intermédioradial du carpe (IRC) avec nécrose avasculaire. À la connaissance des auteurs, il s’agit du premier rapport d’une nécrose avasculaire naturelle l’IRC canin diagnostiquée à l’aide de l’IRM.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

A vascular necrosis (AVN) is uncommonly diagnosed in canine carpal bones (1,2). The diagnosis is challenging due to the small, complex anatomy of the canine carpus and primary use of radiographs for carpal evaluation. This case introduces Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a means to non-invasively assess AVN in the canine carpus.

Case description

A 5-year-old, spayed female Weimaraner dog was presented with the following history. The dog had progressive left forelimb lameness of 6 mo duration. Initial assessment revealed no carpal pain, swelling, or crepitus. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) was prescribed. Lameness progressed to non-weight-bearing and carpal swelling developed. A 30-day course of doxycycline was prescribed as a SNAP 4DX test (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, Maine, USA) and a C6 peptide antibody titer were positive for borreliosis. According to the record, 1 mo later, radiographs were reported to have shown soft tissue swelling, focal periosteal reaction, and an irregular intermedioradial carpal (IRC) articular margin. Comparative radiographs of the right carpus were also abnormal, showing a defect of the distal and dorsal margin of the radius with a corresponding osseous fragment consistent with prior trauma. Synovial fluid assessment of the left carpus was reportedly diagnostic for non-infectious inflammation. Regional biopsy revealed normal collagenous connective tissue. Gabapentin was added to control pain.

The patient was referred for additional diagnostics. A full examination revealed a grade 2/5 left forelimb lameness at walk, left carpal swelling with decreased flexion, and mildly decreased extension with pain on palpation. The right carpus had similar flexion-extension abnormalities without pain.

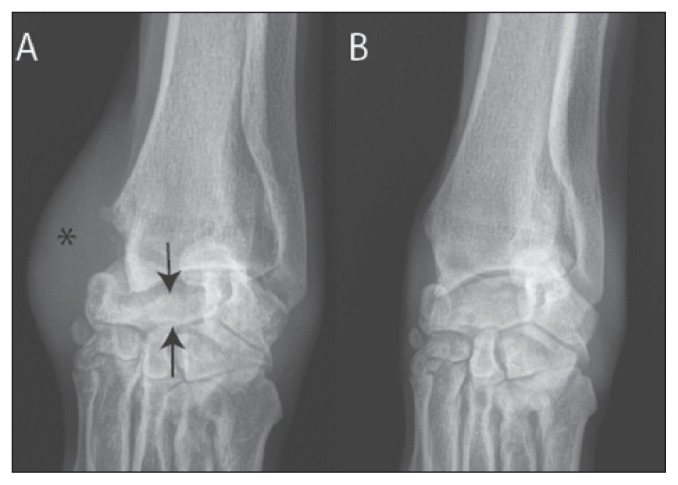

Based on history, radiographs, laboratory work, and physical examination, differential diagnoses included degenerative joint disease, prior trauma, or congenital carpal abnormality, with abductor pollicis longus tenosynovitis to explain the medial soft tissue swelling. Follow-up left carpal radiographs demonstrated increased opacity, trabecular consolidation, and decreased height of the IRC compared to the right (Figure 1), consistent with collapse. Prominent dorsomedial soft tissue swelling was consistent with the site of the reported biopsy. Mineralization and osteophytes were noted, predominantly along the medial margin of the carpus. Radiographs of the right carpus demonstrated thick soft tissues with large mineralization at the carpo-metacarpal joints and cranial margin of the distal radius (not shown).

Figure 1.

Radiographs of the (A) left and (B) right carpus. Notice the collapse of the left intermedioradial carpal (IRC) bone height and dense trabecular pattern (arrows) as well as the soft tissue swelling (*) at the site of prior biopsy.

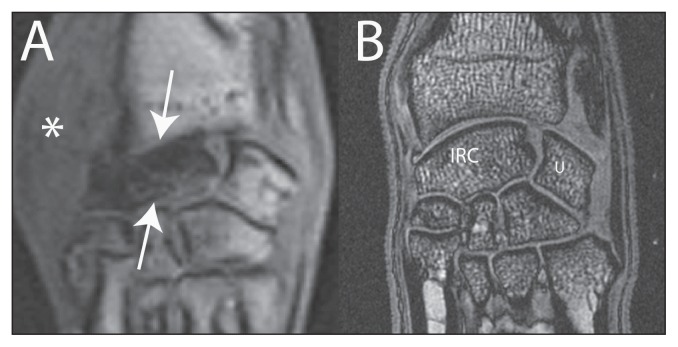

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed (Table 1) using a 1.5T Vantage Atlas MRI (Toshiba, Tustin, California, USA). The left IRC bone displayed diffuse bone marrow edema on fat-suppressed images with low signal intensity on the water sensitive pulse sequences, consistent with diminished vascularity without complete bone devitalization (Figure 2). A short fracture line was identified in the mid-body and seen when evaluated on transverse plane images sequentially (not shown). Additionally, spicules of increased signal intensity and the collapse of the IRC bone supported a fracture. The collapse did not support a neoplastic process as there was no expansion from within the bone. Although a congenital abnormality may produce an abnormal shape to the IRC bone, the central aspect of such a bone would still be anticipated to demonstrate normal marrow signal. The appearance did not support an isolated degenerative process as there was characteristic sparing of the opposing articular margins. The appearance of the IRC bone on MRI was consistent with AVN, fracture, and collapse as has been demonstrated in the human condition. Decreased marrow signal has been shown to correspond histologically with non-viable trabeculae, diminished osteoid, and loss of osteocytes in human cases of carpal AVN (3). Magnetic resonance imaging is useful in diagnosing carpal AVN and may allow an earlier diagnosis than with standard radiographs (4). In the case of the dog in this report, the disease process was advanced and could be diagnosed radiographically and with MRI. Whether the fracture of the IRC bone was a cause or an effect of the AVN could not be determined.

Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging acquisition parameters

| 3 plane STIR | 3D FFE | |

|---|---|---|

| Repetition time (ms) | 3750 | 12 |

| Echo time (ms) | 60 | 5 |

| Inversion time (ms) | 141 | NA |

| Acquisition matrix (Freq × Phase) | 384 × 288 | 288 × 288 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 3 | 1.2 |

| Flip angle | 90 | 20 |

| Echo train length | 13 | NA |

| Field of view (cm) | 20 | 20 |

STIR — Short tau inversion recovery; FFE — fast field echo; NA — not applicable.

Figure 2.

A — Dorsal plane gradient echo magnetic resonance image of the left carpus in the dog of this study, and B — high resolution dorsal plane gradient echo of a normal dog carpus. Note the global loss of signal of the left intermedioradial carpal (IRC — arrows) bone without loss of signal on the articular margins of the adjacent carpal bones. The medial soft tissues are thick (*), attributed to recent biopsy.

Discussion

Acascular necrosis indicates devitalization and bone death from loss of vascularity. The etiology of AVN in humans is a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors (5), including acute trauma, chronic repetitive trauma, abnormal loading, morphologic variation, or vascular predisposition/injury (5), and glucocorticoid use, smoking, and vasculitis.

Magnetic resonance imaging is a sensitive and specific test for carpal bone AVN and may allow early disease detection (6). The appearance of AVN on MRI can range from a bone marrow edema pattern with subtle trabecular consolidation to frank subchondral fibrosis and completely devitalized marrow, manifested as low signal intensity on all fluid sensitive pulse sequences. Later stages of AVN may display secondary fracture and collapse.

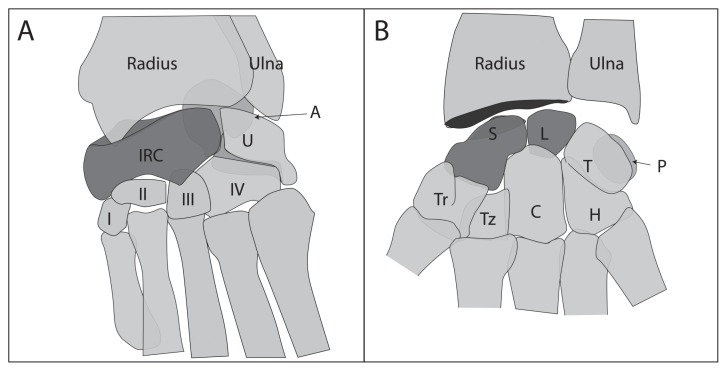

The lunate and scaphoid are comparable to the mammalian intermediate and radial carpal bones, respectively. In carnivores, the intermediate, radial, and central ossification centers fuse to form the single IRC bone (Figure 3), which is colloquially termed the “radial carpal” bone. Atraumatic carpal AVN in humans has been widely described, with the scaphoid (Preiser’s disease) and lunate (Kienböck’s disease) bones as the 2 most commonly affected (7). Traumatic AVN in humans has been correlated with the unique vascular distribution of the scaphoid, in which the proximal pole is a terminal zone predisposed to vascular compromise. It is uncertain if the canine IRC shares a similar vulnerable vascular pattern. Description of the blood supply to the canine carpal bones is limited, with few anatomic diagrams available (8,9). Gross dissection of the carpus has shown both mid-dorsal and palmarodistolateral foramen in the IRC bone corresponding with nutrient arteries. The dorsal nutrient artery arises from the dorsal carpal rete, formed from the dorsal carpal branch of the radial artery and a branch of the caudal interosseous artery (8,9). The palmar nutrient artery arises from the deep palmar arch. The internal IRC vascular distribution has not been described. Vascularity likely varies among dogs and additional studies are needed to determine if individual alterations in blood supply to the IRC is a predisposing factor to this condition.

Figure 3.

Comparison of (A) the canine carpus and (B) the human wrist. The intermedioradial carpal (IRC) bone represents the fusion of the scaphoid and the lunate (highlighted bones). I–IV — first through fourth carpal bones, respectively; IRC — intermedioradial carpal; U — ulnar carpal bone; A — accessory carpal bone; Tz — trapezoid; Tr — trapezium; C — capitate; H — hamate; P — pisiform; T — triquetrum; L — lunate; and S — scaphoid.

Human carpal AVN presents with wrist pain, loss of grip and decreased range of motion, but the canine correlate has not been extensively described. Dogs with previously reported IRC and accessory bone AVN were noted to have a poorly defined lameness similar to the dog in this report. The dog in this study had a prolonged lameness that did not respond to NSAIDs and gabapentin. This may be explained as bone pain secondary to ischemia and progressive collapse may not resolve with anti-inflammatory agents particularly if the bone is continually loaded. The canine thoracic limbs are disproportionately loaded during normal ambulation; therefore, even mild activity such as walking could result in sustained microtrauma and pain. Treatment in humans with AVN of the scaphoid or lunate ranges from rest, microfracture drilling, vascular bone grafting, intercarpal fusion, or proximal row carpectomy. The 2 prior cases of canine carpal AVN were treated with arthrodesis, which was successful in resolving pain (1,2). Notably, vascular grafting techniques have been used in canine models of induced AVN of the IRC bone (5,10,11), but have not been incorporated into clinical veterinary protocols. Surgery was not elected in the dog in this report. At a 2-year follow-up, the dog herein had improved with time on NSAIDs. Additional imaging was not elected.

The MRI appearance of experimentally induced AVN in the dog has been described (5), but MRI has not been used to diagnose naturally occurring canine AVN. In previous clinical reports, dogs were diagnosed via biopsy (1,2), which is invasive and may carry associated morbidity in already devitalized bone. The current patient was assessed non-invasively using MRI, the results of which paralleled the findings previously described in the induced canine condition (10), including diffuse edema pattern on fat suppressed images and a substantial signal loss throughout the IRC bone on other pulse sequences. Additional biopsy of devitalized bone may have resulted in further morbidity of the carpal bone and/or trauma of regional soft tissues. Biopsy of the small IRC bone was not deemed necessary for the diagnosis in our case report as the diagnosis was typical for the MRI appearance of AVN.

In summary, a cause for suspected IRC AVN in the patient in this report was not determined. This patient was at a later stage of this condition and a fracture was present. The fracture may have been the result of or the cause of the AVN. This patient had no long-term steroid use, systemic inflammatory disease, or other known extrinsic variables. Chronic repetitive trauma was a possibility. In conclusion, MRI is an ideal modality to non-invasively diagnose this condition and should be considered prior to biopsy of areas of potential vascular compromise. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

Disclaimers: Drs. Pownder and Koff receive institutional research support from General Electric Healthcare.

References

- 1.Aiken MJ, Stewart JE, Anderson AA. Avascular necrosis of the canine radial carpal bone: A condition analogous to Preiser’s disease? J Small Anim Pract. 2013;54:374–376. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris KP, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Idiopathic ischemic necrosis of an accessory carpal bone in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243:1746–1750. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.12.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desser TS, McCarthy S, Trumble T. Scaphoid fractures and Kienbock’s disease of the lunate: MR imaging with histopathologic correlation. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:357–361. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristiani G, Cerofolini E, Squarzina PB, et al. Evaluation of ischaemic necrosis of carpal bones by magnetic resonance imaging. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15:249–255. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_90_90132-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willems WF, Alberton GM, Bishop AT, Kremer T. Vascularized bone grafting in a canine carpal avascular necrosis model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2831–2837. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1893-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox MG, Gaskin CM, Chhabra AB, Anderson MW. Assessment of scaphoid viability with MRI: A reassessment of findings on unenhanced MR images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W281–286. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoller D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans H, Christensen G. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar M. Veterinary Anatomy. North Grafton, Massachusetts: Tufts University College of Veterinary Medicine; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunagawa T, Bishop AT, Muramatsu K. Role of conventional and vascularized bone grafts in scaphoid nonunion with avascular necrosis: A canine experimental study. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25:849–859. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.8639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu YK, Bishop AT, Kato T, Adams ML, Wood MB. Experimental carpal reverse-flow pedicle vascularized bone grafts. Part I: The anatomical basis of vascularized pedicle bone grafts based on the canine distal radius and ulna. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25:34–45. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.jhsu025a0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]