Abstract

Context:

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Iranian women. Although survival rate of breast cancer patients has been increased some distresses affect the patients’ quality of life negatively. the effectiveness of self-care education, particularly in the sociocultural context of Iran, has not been adequately investigated.

Aims:

This study aims at evaluating the effectiveness of nurse-led self-care education program on quality of life in this patients.

Settings and Design:

A controlled trial as pretest and posttest design was conducted in Sayyed-Al-Shohada Hospital in Isfahan in 2012.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty patients with breast cancer were assigned to either the nurse-led self-care education program (n = 30), or to routine care (n = 30). Quality of life was measured at the time of recruitment and also 3 months after the intervention by the instrument of the National Medical Center and Beckman Research Institute.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data were analyzed by SPSS (version 16) software using T-independent, T-paired and χ2, and Fisher's exact tests.

Results:

The intervention group had significantly greater improvements in quality of life status (P < 0.05). Furthermore, self-care education caused a significant increase in the quality of life score related to physical (P = 0.00), psychological (P = 0.00), social (P = 0.00), and emotional (P = 0.00) dimensions.

Conclusions:

Quality of life in patients with breast cancer can be improved by participating in a nurse-led self-care education program. It is suggested that self-care education to be added to the routine nursing care delivered to these patients.

Keywords: Breast cancer, quality of life, self-care education

INTRODUCTION

According to the latest records issued by World Health Organization, cancer is considered as the second cause of mortality following cardiovascular diseases all over the world.[1] In Iran, cancer is the third cause of mortality[2] and it has been estimated that among all cancer types, breast cancer has the highest rate of incidence among women.[3,4] Different studies show that the age of being affected by this disease in Iran is up to one decade less than that in other countries.[5,6,7,8]

Based on National Report of Cancer Records in 2009 in Iran (the latest surveys available), Isfahan has the second rank following Tehran for breast cancer incidences in women. Breast cancer has the second highest rate of incidence following acute lymphoblastic leukemia in this province.[9]

In spite of increasing survival rate of patients with breast cancer, many women with this disease suffer from long-term physical and psychological problems resulting from the existing combined treatments,[10] for some of the cancer treatments can often cause numerous lasting adverse effects and have a significant effect on quality of life of breast cancer survivors.[11] On the other hand, completing treatment courses, patients with cancer are confronted with a series of challenges, which are different from the challenges faced in days and weeks after diagnosis. In other words, upon diagnosing the disease, patients feel stress and distress and are frightened thinking of early death, disease prognosis and imposed roles and responsibilities. After a while, these challenges are replaced by chronic depression, financial problems regarding disease treatment, psychological and physical complications of chemotherapy/radiotherapy, and even surgery. In addition, focus of the patient with the cancer in survival time changes from fear of death, distress regarding full treatment and recovery or adjustment with activities related to the treatment into the issues related to long-term survival.[12] These people face issues like problems in sexual relations and change in mental image, fatigue, comorbidities resulting from cancer treatments, including incidence of secondary cancers,[13] risk of psychological distresses, depression periods and disturbances in life style. In fact, these people may experience painful symptoms and complaints even several years after diagnosis.[10] Therefore, there is a need for attempts toward enhancing physical performance and quality of life of this category of patients.[11]

Women are one of the most important fundamentals in every family and society; hence, improving quality of life of women with breast cancer not only improves their survival, but also increases quality of life and further coherence of the family structure.[10,11] Necessity of employing some measures regarding controlling disease and treatment complications and enhancing quality of life of the patients is highly evident,[12] as existence of a long lasting disease or even its resulting physiologic and psychological symptoms and defects can degrade quality of life in later stages and in turn increase susceptibility of the individual to other defects.[3]

Research has shown that physical failure of the individual makes her aware of her potential death and her spiritual needs become in turn more than before.[14] Physical symptoms and complaints in these patients can influence all main aspects of quality of their lives, including physical health, psychological health, social interests and spiritual health.[15]

Quality of life at the present is one of the most fundamental variables of interest in treatment caring investigations and provides healthcare specialists with a collection of practical useful information on the patients’ health status. Quality of life is an important parameter in evaluating effects of the disease on all dimensions of the individual's life as well as evaluating the effect of medical interventions on overall performance of the individual in the life.[16]

Previous studies have emphasized on effectiveness of self-care education programs in patients suffering from back pain,[17] knee pains,[18] arthritis,[19] neck pain,[20] angina pectoris,[21] epilepsy,[22] cancer under chemotherapy,[23] esophageal cancer[24] and heart failure[25] and most of them have evaluated different variables like pain, recurring doctor visits, treatment costs, knowledge, performance, and quality of life as outcome variables. However, studies on the effect of nurse-led self-care education on quality of life of the patients, particularly in a sociocultural context of Iran, are not available.

Studies show that patients with breast cancer depend on treatment caring providers for receiving the information required on their disease and controlling their situation.[26] Nurses, as one of the members of treatment team, have an important role in diagnosis, treatment, and caring patients with cancer and as they spend more time with the patient compared to the other treatment team members, they may be the first people who can recognize the needs of patients and their families and be effective in controlling disease complications and treatment as well as enhancing quality of life of the patients.[10,11]

One of the most fundamental tasks of the nurses is patient education.[27] They are in a very key position affecting patients’ life positively through education and making stable changes in their lives.[28] However, nurses do not play their important and effective role in educating patients and their families appropriately.[29]

Given the above-mentioned points, one can see that self-care influences quality of life; but it is not clear if specific situations of the patients under treatment, given their physical and psychological situations, can have an effect on self-care. In addition, researchers try to identify whether this method can influence individuals’ self-care and in turn quality of their lives as a practical tool.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study is a clinical trial of pretest and posttest design performed in the control and treatment groups of women with breast cancer under chemotherapy. The study population included all the patients with breast cancer under treatment in treatment and educational center of Sayyed-Al-Shohada Hospital in Isfahan. Based on the statistical formula for determining sample size in intervention research with confidence interval of 95% and test power of 80%, necessary number of samples in each group was determined as 28 people and was considered 30 people for more confidence. Hence, the total sample size was 60. Inclusion criteria of the study included suffering from breast cancer, being it the age range of 18–55, being in the treatment process (chemotherapy/radiotherapy) with or without mastectomy, being aware of their own disease, being hospitalized in different departments of the hospital (surgery, internal medicine, outpatient chemotherapy), being in performance level of 0–2. Exclusion criteria of the study included reluctance of the patient to continue participation and any special medical (such as deterioration of physical situation and death) and nonmedical (such as transferring the patient to another medical center) situation, which inhibited the individual from continuing participation in the study.

In this study, collection of the data on quality of the life of the participants in the research was performed using standard instrument for investigation of quality of life of the patients with breast cancer associated to National Medical Center and Beckman Research Institute, which measures quality of life in four dimensions of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health.[30] This tool evaluates specifically quality of life of the patients with breast cancer, while many tools used today in the studies related to the patients with breast cancer are not specific to breast cancer and consider the patients with cancer generally.[31] This tool has been frequently used by Iranian researchers, and its reliability and validity has been verified in a sociocultural context of Iran. This questionnaire has 44 items where scoring of each item is based on a measure from 0 to 10, so that the score 0 corresponds to the worst mode and the score 10 to the best mode. Scoring in several items on this tool (1–7, 9, 10, 17–29, 31, 33–37, 41) is reverse compared to the other items. Given the reports of other studies, this tool has acceptable validity in a sociocultural context of Iran and its reliability has been reported as 0.80 with Cronbach's alpha.[32]

In the present study, the researcher started the research passing the stages of proposal approval and acquiring the permission from Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. In Sayyed-Al-Shohada Medical Center, all the patients diagnosed for breast cancer by all specialists of this center are introduced to breast cancer screening center without respect to the cancer development degree or the type of treatment and medical records are prepared for them. Hence, the researcher sampled all patients being introduced to breast cancer screening center. The samples included all patients with breast cancer who needed hospitalization and had a performance level of at least 2. Performance levels of the studied units were determined based on Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance level criterion formulated in World Health Organization. This criterion categorizes patients’ performance levels from 0 to 4.[9] The best performance level corresponds to the level 0 and the worst one to the level 4. At the moment, this criterion is used as one of the criteria for determining performance level of cancer patients under treatment.

Sampling was as time blocks in such a way that first all the hospitalized patients who had the inclusion criteria were entered the study as intervention group and after completing this group, all the patients having inclusion criteria of the study were selected as the control group. Being informed of the study purposes and of being free to participate in or leave the study, all the subjects were asked to submit an informed written consent. Immediately upon recruiting the subjects to the study, they were asked to fill out the two-part questionnaire including demographic and quality of life information. The subjects filled out the questionnaire in a quiet environment (the private room in nursing clinic for patients’ education) and the required time was allotted based on their need. For intervention group, three 60–90 min sessions of self-care education were held on recognition of cancer concept in general and breast cancer in particular, existing treatments in cancer (chemotherapy or radiotherapy), complications and employing prevention and caring strategies in treatment complications (including frequent complications of breast surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), emergency alarming symptoms of cancer, and importance of treatment follow-up. This education program was carried out in groups (of 3–5) by two nursing instructors who were faculty members of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (at postgraduate and Ph.D level) in nursing clinic of patient education in breast cancer screening center of Sayyed-Al-Shohada Medical and Educational Center. All the studied units filled out the same questionnaire again after 3 months from the last education session. The control group also filled out the questionnaire upon entering the study and were then included in routine treatment caring process; and after 3 months, they filled out the same questionnaire again. Selecting 3 months as the period required in this study was based on similar literature.[24] It should be noted that in routine cares provided to these patients, there was no programmed self-care education. No participant left the study. Finally, the data collected were analyzed using SPSS V16 [SPSS Inc: Chicago, IL.] and employing statistic T-independent, T-paired and χ2, and Fisher's exact tests considering confidence (alpha) as 95%.

RESULTS

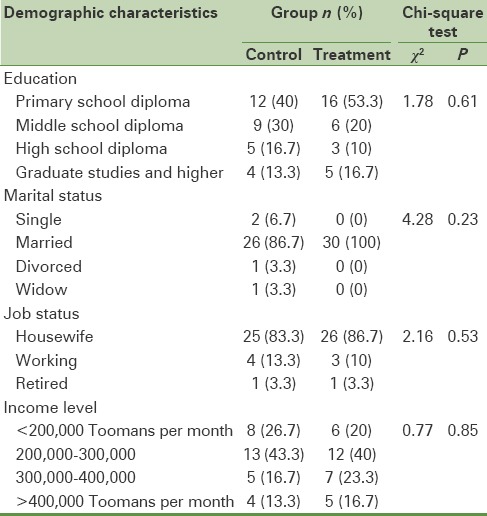

The research results showed that most of the patients in both groups were married, housewife, at average age of 44, had primary school diploma, and were suffering from breast cancer for average 17 months. Most of them had no background of suffering from breast cancer in their close relatives. χ2 and Fisher's exact tests showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of background variables of education level, marital status, job status, husband education, number of the months suffering from cancer, background of suffering from breast cancer in relatives, age, and level of family income and the both groups were homogenous in terms of measured basic variables [Table 1]. No sample attrition was happened during the study.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the study

Statistical T-paired test showed that in the control group upon entering the study and after 3 months, there is no statistically significant difference between average score of physical dimension of quality of life (P = 0.69), psychological dimension of quality of life (P = 0.93), social dimension of quality of life (P = 0.14), spiritual dimension of quality of life (P = 0.55), and total score of quality of life (P = 0.71).

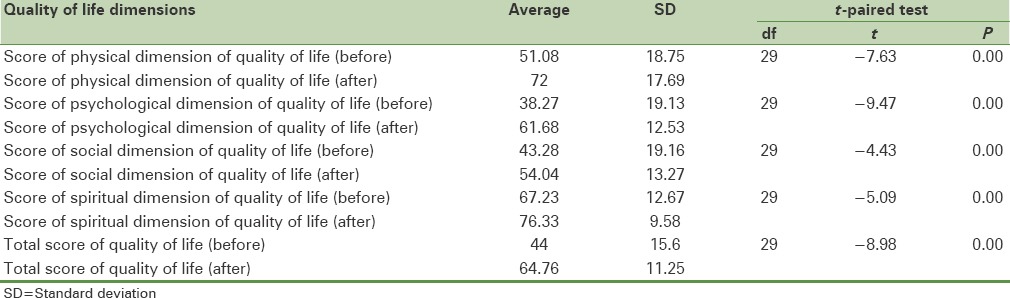

Statistical T-paired test showed that in the intervention group immediately before and after 3 months from performing self-care education, there is a statistically significant difference between average score of physical dimension of quality of life (P < 0.0001), psychological dimension of quality of life (P < 0.0001), social dimension of quality of life (P < 0.0001), spiritual dimension of quality of life (P < 0.0001), and total score of quality of life (P < 0.0001).

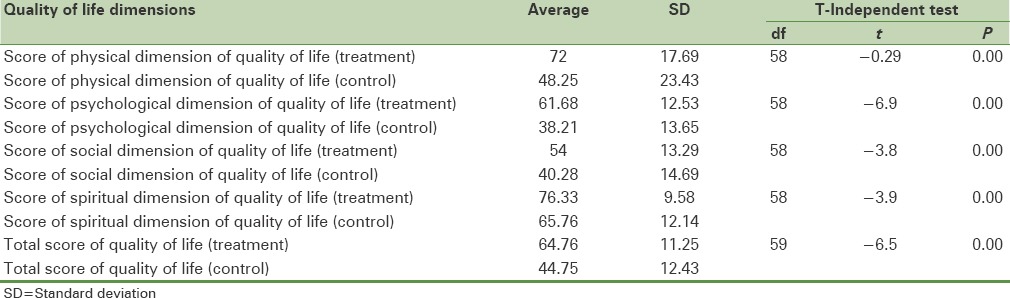

T-independent test showed that despite the lack of a statistically significant difference in average total score and different dimensions of quality of life between the intervention group and the control group in initial measurement upon entering the study, these averages have significant difference in physical health dimension (P < 0.0001), social dimension (P < 0.0001), psychological dimension (P < 0.0001), spiritual dimension (P < 0.0001), and total score of quality (P < 0.0001) after 3 months [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Comparing average scores of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual heath dimensions and total quality of life score before and after self-care education intervention in the treatment group

Table 3.

Comparing average scores of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual heath dimensions and score of total quality of life between the treatment and the control groups after self-care education intervention

DISCUSSION

The research results showed that quality of life of the patients with breast cancer has been enhanced under the influence of self-care education and this improvement has not been only related to the total score of the quality of life but has occurred in all its dimensions. Thus, it can be said that self-care education enhances physical, social, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of quality of life of the patients with breast cancer. Previous studies investigating the effectiveness of self-care education in other patients have also emphasized on this point. Among them, focusing on breast cancer survivors and based on his study results, Loh et al. states that all dimensions of quality of life increased significantly in the intervention group after performing a 1-month self-management program compared with the control one.[33] Of course, Loh et al. has emphasized on self-management education as his intervention. The difference between self-care education and self-management education is that unlike self-care education emphasizing more on transferring knowledge and skill related to self-care, self-management education emphasizes on decision making skill.[34] In his study in 2011, Loh et al. also showed that self-management education program has a remarkable effectiveness in the longer period of 2 years as well.[35] However, some studies focusing on self-care education have reported homogenous results in different diseases.

Among them, Wengström et al. focus on their self-care program in patients with breast cancer under radiation therapy and emphasize that if this program is planned according to patients’ needs, it can improve their quality of life.[36] Cherkin et al. report the effect of self-care education on reducing back pain[17] and Mazzuca et al. confirm the positive effect of self-care education on health status of the patients with knee pain.[18] Effectiveness of self-care education have been also confirmed in the patients with arthritis, neck pain, angina pectoris, epilepsy, cancer under chemotherapy, esophageal cancer[24] and heart failure.

One of the most important caring points in the patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy surgery is education for preventing lymph edema of the hand, which was one of the aspects of self-care education in the present study as well. Although only quality of patients’ lives has been considered as an outcome variable in the present study, some studies have investigated the effectiveness of nurse-led education program on lymph edema of hand.[37] These studies have confirmed that education can prevent developing such condition. Hand edema not only imposes psychological concerns on the patient in terms of beauty and appearance, but also can cause physical problems such as pain, heaviness, and interference with daily activities.[38]

It should be emphasized that in the present study, self-care education of the patients was often performed in small groups. Studies have consistently showed that one of the fundamental obstacles on the way of nurses in patient education is time limitation. So, some studies have pointed to the effectiveness of education through media (such as video films, educational tapes, and computer and internet programs) and telephone.[39] Many studies measuring quality of life as an outcome variable have not been limited only to expressing total score of quality of life, and its dimensions have also been analyzed. Similarly, in the present study, statistical analyses were performed for total score of quality of life as well as its dimensions. One of the controversial findings in this regard is that among different dimensions of quality of life, the highest score in dimensions of quality of life in both groups belonged to the spiritual dimension. In their qualitative study, Taleghani et al. have also pointed to the role of religious issues in the lives of the women with breast cancer in Iran and saw it fundamental in enhancing the adjustment of these patients with their disease.[16] On the other hand, the lowest score in different dimensions of quality of life in the patients participating in the research belonged to the psychological dimension. This finding is also seen in the study of Arndt et al. Based on the results of their study on the women with breast cancer, they reported lower score of emotional dimension performance in these patients compared with the population and the other dimensions were at desired levels.[40] This shows the necessity of focusing nursing interventions on these areas. On the other hand, intervention in these dimensions needs participation of other members of the family especially the husbands as a supporting source, as the patients with breast cancer need more attention and companion by their husbands due to fear from being abandoned by them.

Research limitations

One of the most important limitations of this study was impossibility of full randomizing of the samples and due to some organizational issues, the researcher was made to use time blocks. Although statistical tests showed homogeneity of both groups in terms of background variables, randomization effect in homogenizing hidden variables is not unclear for anyone. Another limitation of the research was lack of longer follow-up period (>3 months), as the importance of follow-up and ensuring later and lasting effectiveness of the intervention and if necessary, repeating the educations cannot be ignored. In addition, cases like death of close relatives or occurrence of comorbidity and their effects on quality of life had not been predicted in this study. In further researches, it is recommended to consider these factors and the methods for controlling their influence on the quality of life and interpreting their score after the intervention.

CONCLUSION

Given the effectiveness of self-care education program used in this research in order to enhance quality of life of the patients with breast cancer, this program is suggested to be performed in extensive scope by nurses working in cancer departments, especially breast cancer. In other words, it seems that if self-care education is added to the routine cares provided to these patients by nurses, it can influence treatment results and highlight the importance of nurses’ roles. On the other hand, it is recommended that further studies investigate longer-term effect of such programs and plan individualized education program in formulating their own education program, focusing and emphasizing on unique needs of each patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was extracted from research plan No. 287161 supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors hereby show their sincere gratitude to the research subjects, the Hospital manager, and the manager of screening center of Sayyed-Al-Shohada Medical and Educational Hospital in Isfahan who contribute and cooperate in providing an appropriate environment for patients’ education.

REFERENCES

- 1.France: World Health Organization; 2011. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Disease, Countries Profile. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousavi SM, Gouya MM, Ramazani R, Davanlou M, Hajsadeghi N, Seddighi Z. Cancer incidence and mortality in Iran. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:556–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khodabakhshi R, Gohari M, Moghadamifard Z, Foadzi H, Vahabi N. Survival without disease in breast cancer patients and investigation of factors. Razi Med Sci J. 2011;18:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saki A, Hajizadeh E, Tehranian N. Evaluating the risk factors of breast cancer using the analysis of tree models. Horiz Med Sci. 2011;17:60–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahkhodabandeh S, Piri Z, Biglo M, Asadi M, Chokhmaghi N. Breast cancer in Iran: Trend of Iranian researchers in MEDLINE. Breast Cancer Dis J. 2009;2:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norizadeh R, Bakhtariaghdam F, Sahebi L. Investigation knowledge and health behaviors of women who coming to health centers of Tabriz about cancer and screening 2010. Breast Cancer Dis J. 2010;3:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salimi S, Karimian N, Sheikhan Z, Alavi H. Investigation breast cancer screening test and related factores of women who coming to health centers of Ardebil 2008. Ardebil Med Sci Univ J. 2009;10:310–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebrahimi SM. Investigation Effect of Ginger on Nausea and Vomiting of Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: Ms Thesis, Medical Science Tehran University. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Report of Cancer Records, Ministery of Health and Medical Education, Center of Disease Control and Preventation, Non-contagious Deputy, Cancerorgan, The Cancer Organ, Tehran. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milne HM, Wallman KE, Gordon S, Courneya KS. Effects of a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:279–88. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheema BS, Gaul CA. Full-body exercise training improves fitness and quality of life in survivors of breast cancer. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:14–21. doi: 10.1519/R-17335.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dow KH. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. Nursing Care of Women with Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smeltzer SC, Bare BG, Hinkle JL, Cheere KH, Kluwer W. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins; 2010. Brunner and Sudarth's Textbook of Medical-surgical Nursing; pp. 1460–1700. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldacchino D, Draper P. Spiritual coping strategies: A review of the nursing research literature. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:833–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews SC. Caregiver burden and symptom distress in people with cancer receiving hospice care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:1469–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taleghani F, Yekta ZP, Nasrabadi AN. Coping with breast cancer in newly diagnosed Iranian women. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:265–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03808_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, Barlow W, Kaptchuk TJ, Street J, et al. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1081–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Hanna MP, Melfi CA. Reduced utilization and cost of primary care clinic visits resulting from self-care education for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1267–73. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1267::AID-ANR25>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goeppinger J, Arthur MW, Baglioni AJ, Jr, Brunk SE, Brunner CM. A reexamination of the effectiveness of self-care education for persons with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:706–16. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans R, Bronfort G, Bittell S, Anderson AV. A pilot study for a randomized clinical trial assessing chiropractic care, medical care, and self-care education for acute and subacute neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:403–11. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballegaard S, Johannessen A, Karpatschof B, Nyboe J. Addition of acupuncture and self-care education in the treatment of patients with severe angina pectoris may be cost beneficial: An open, prospective study. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:405–13. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahebzamani M, Shakori A, Alilo L, Rashidi A. Investigation effect of self care education on knowledge and function of epileptic patients in hospitals of Tehran scientific university 2007. Ardabil Med J. 2008;20:284–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghavam-Nasiri MR, Heshmati Nabavi F, Anvari K, Habashi Zadeh A, Moradi M, Neghabi G, et al. The effect of individual and group self-care education on quality of life in patients receiving chemotherapy: A randomized clinical Trial. Iran J Med Educ. 2011;11:874–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pool MK, Nadrian H, Pasha N. Effects of a self-care education program on quality of life after surgery in patients with esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2012;35:332–40. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3182605f86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghahramani AR, Kamrani F, Mohamadzadeh SH. Effect of self care education on knowledge, function and rehospitalizationof congestive heart failure. Nursing Research Journal. 2010;89:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wengström Y. Are women with breast cancer receiving sufficient education and information about their treatment? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:62–3. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wingard R. Patient education and the nursing process: Meeting the patient's needs. Nephrol Nurs J. 2005;32:211–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syx RL. The practice of patient education: The theoretical perspective. Orthop Nurs. 2008;27:50–4. doi: 10.1097/01.NOR.0000310614.31168.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avsar G, Kasikçi M. Evaluation of patient education provided by clinical nurses in Turkey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrel BR, Grant M. National Medical Center. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 01]. Available from: http://www.http://prc.coh.org/QOL-CS.pdf .

- 31.Chopra I, Kamal KM. A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taleghani F, Khajehaminian MR, Khalifezadeh A, Karimian J, Hajahmadian H. The effect of exercise on physical aspect of quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2009;14:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loh SY, Packer T, Chinna K, Quek KF. Effectiveness of a patient self-management programme for breast cancer as a chronic illness: A non-randomised controlled clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:331–42. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loh SY, Chew SL, Lee SY, Quek KF. Quality of life in breast cancer survivors: 2 years post self-management intervention. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wengström Y, Häggmark C, Forsberg C. Coping with radiation therapy: Strategies used by women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:264–71. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sisman H, Sahin B, Duman BB, Tanriverdi G. Nurse-assisted education and exercise decrease the prevalence and morbidity of lymphedema following breast cancer surgery. J BUON. 2012;17:565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matory P. Tehran: Heidary Publication; 2014. Breast Cancer: Clinical Guideline for Nurses and Nursing Students. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryhänen AM, Siekkinen M, Rankinen S, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. The effects of Internet or interactive computer-based patient education in the field of breast cancer: A systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arndt V, Merx H, Stürmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Age-specific detriments to quality of life among breast cancer patients one year after diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]