Abstract

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a rare extramedullary tumor composed of immature cells of myeloid lineage that destroy the original tissue architecture in which it is found. It is most commonly identified in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia, and less often in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) and other myeloproliferative disorders. It is most commonly reported in the periosteum, bone, skin, and lymph nodes but has been reported in many other sites of the body. Herein, we describe a case of MS involving the periprostatic tissue and review of literature of MS of the prostate. Our patient was initially diagnosed with MDS and was in remission following successful treatment. Six months later, the patient was diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma, and MS of the periprostatic tissue was incidentally discovered in the postprostatectomy pathology specimen. An extensive review of literature from 1997 to 2014 revealed a total of eight cases of MS involving the prostate. Of the eight cases of MS of the prostate, four were primary MS (absence of a history of leukemia) and four were secondary MS. Three received local radiation to the prostate with relief of obstructive symptoms, and one of them had a repeat prostate biopsy negative for leukemic cells. Despite being a rare entity, MS should be considered as a differential diagnosis of soft tissue masses, especially in patients with a history of hematological malignancies.

Keywords: Acute myelogenous leukemia, chemotherapy, extramedullary leukemia, prostate biopsy, radiation

INTRODUCTION

Myeloid sarcomas (MSs) are solid tumors with extramedullary (EM) proliferation of immature cells of one or more of the myeloid lineage that disrupt the normal architecture of the tissue in which it is found.[1] It is also known as chloroma (green color characteristic of myeloperoxidase [MPO] enzyme), granulocytic sarcoma, myeloblastoma, and EM myeloid cell tumor.[2,3,4] MS is recognized as a distinct entity under acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and related myeloid neoplasm in the 2008 World Health Organization classification.[5] MS develops most commonly in the setting of AML but can occur in association with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and other myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs). MS can be diagnosed simultaneously with, during the acute phase or as a relapse of AML, MDS and MPD known as secondary MS. Rarely, it can precede AML at which the bone marrow studies reveal no hematological disease known as primary or isolated or nonleukemic MS.[6] MS involving the prostate is extremely rare with only nineteen cases reported in the literature.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] So far, only one review article of MS of the prostate has been published in the year 1996, describing a total of nine cases.[16]

CASE REPORT

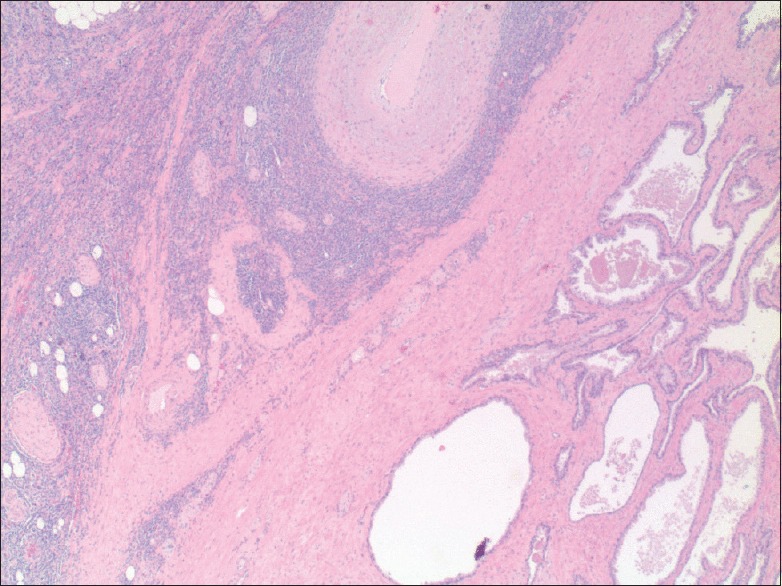

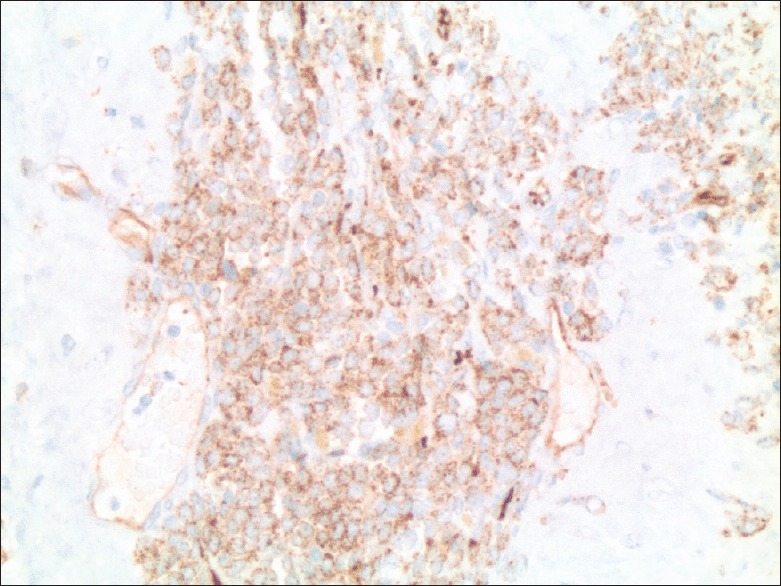

A 66-year-old African American male patient was diagnosed with MDS – refractory anemia with excess blasts 1 type. He received four cycles of decitabine, without significant improvement and remained dependent on allogeneic packed red blood (PRB) cells. Eight months later, he underwent bone marrow biopsy that showed a persistent increase in blast cells (8% blasts cells). He was started on fludarabine, busulfan followed by allogeneic PRB stem cell transplantation. Treatment was complicated by acute graft versus host disease (GVHD-with mild skin rash and elevation of liver function tests) that resolved immediately with an increase in tacrolimus dose. One year to the initial diagnosis, bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of neoplastic cells and flow cytometry was negative and the patient achieved complete remission. The patient had a history of rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels for one year, but the prostate biopsy was deferred due to his unstable hematological condition. Six months into remission, after stabilization of his hematological condition, the patient underwent a transrectal prostate biopsy (TRPB) that revealed Gleason 7 prostate cancer. He underwent robotic radical prostatectomy and histopathology specimen showed Gleason score 7, prostate adenocarcinoma involving <10% of prostate with no evidence of extraprostatic extension or seminal vesicle involvement and with negative surgical margins. Periprostatic tissue showed infiltrates of immature single cells resembling blast cells, but no blasts cells were noted in the prostate [Figure 1]. Immunohistochemical staining of periprostatic tissue identified neoplastic cells (T-cells and B-cells) positive for CD3, CD20, CD34, and CD117 suggesting myeloblasts consistent with a diagnosis of periprostate chloroma [Figure 2]. Subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed low evidence of aberrant myeloid blasts (<5%). Repeat bone marrow biopsy 4 months following surgery was consistent with transformation to AML with 50% blasts. He received induction chemotherapy (FLAG regimen - fludarabine, high-dose cytarabine, and granulocyte colony stimulating factor) and donor lymphocyte infusion. The patient responded well to the treatment without any GVHD and bone marrow biopsy was hypocellular without evidence of leukemia and currently in remission. The patient is alive one year following the diagnosis of MS.

Figure 1.

Prostate tissue and tumor within the periprostatic tissue (×20)

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical marker typically staining myeloid blasts (×200)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive literature review was performed through PubMed, Ovid Web databases, and Cochrane Library from 1997 to 2014, using the keywords chloroma, MS, granulocytic sarcoma, and EM leukemic infiltration involving the prostate and the periprostatic tissue. Due to recent advances in diagnosis and management, we have omitted the articles before 1996 and reviewed the articles from 1997 to 2014. Articles were screened with the above-mentioned terms, specific for myeloid lineage tumors including acute myeloid leukemia, MDS, and MPDs.

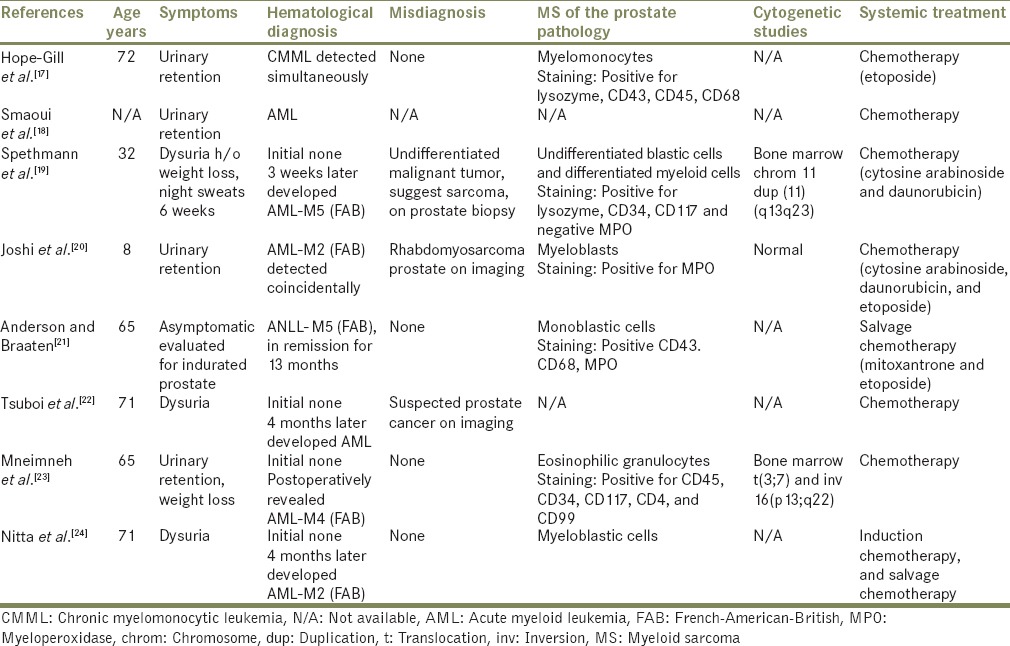

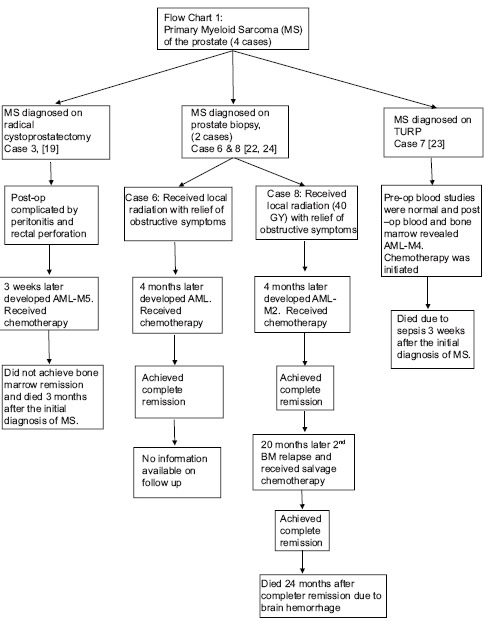

RESULTS

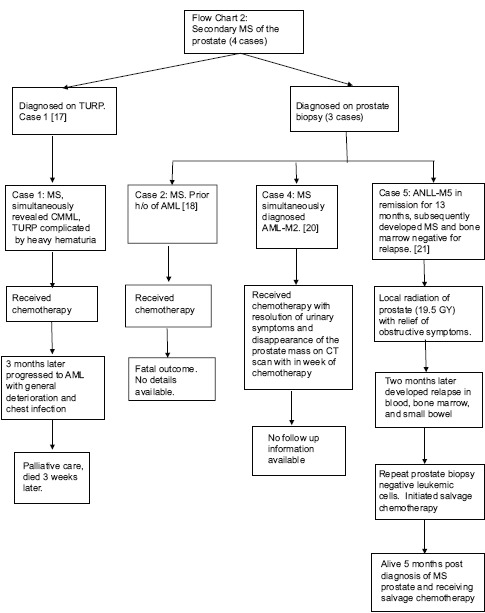

A total of eight cases with extensive infiltration of the prostate with immature myeloid cells were found and are outlined in Table 1.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] Four were diagnosed as primary MS and four as secondary MS [Flow Charts 1 and 2]. The four with primary MS developed AML within a period of 4 months of initial diagnosis. The age of presentation of MS of the prostate was between 8 and 72 years old, with a mean of 55 years. Our patient was 66-year-old, had a history of MDS in remission and later developed EM relapse in the periprostatic tissue. Seven patients had urinary symptoms including dysuria, urinary retention, or urgency, prompting surgical intervention, and one was evaluated for indurated prostate.[21] Most of the patients had enlarged or indurated prostate on physical examination or on the imaging studies. Our patient was asymptomatic and was evaluated for rising PSA levels with an enlarged prostate gland on rectal examination, without any induration. In this group, three were initially misdiagnosed as undifferentiated malignant sarcoma on prostate biopsy,[19] rhabdomyosarcoma on the computer tomography (CT) scan,[20] and suspected prostate cancer on initial imaging studies.[22] Their diagnosis of MS was confirmed only on further evaluation immunohistochemically. Five were diagnosed MS on prostate biopsies, two on a postsurgical specimen of transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) tissue, and one on radical cystoprostatectomy specimen. Our patient was diagnosed with prostate cancer on TRPB and later found to have periprostatic tissue chloroma on radical prostatectomy specimen. After the diagnosis of MS of prostate was made, three received local radiation with relief of obstructive symptoms and one of them had repeat prostate biopsy negative for EM leukemia (EML). Four died, three in a period of 4 months of diagnosis of MS and one after 4 years of diagnosis. In addition to the four, one patient had a fatal outcome; however, no detailed information was available.[18] The details on the diagnosis, treatment, and progression of the disease of each patient are described in Flow Charts 1, 2 and Table 1.

Table 1.

Myeloid sarcoma of the prostate

Flow Chart 1.

Primary myeloid sarcoma of the prostate (four cases)

Flow Chart 2.

Secondary myeloid sarcoma of the prostate (four cases)

DISCUSSION

MS is a rare EM leukemic tumor comprising immature myeloid cells that disrupts the architecture of the tissues in which it is found. The etiology of MS or any EM disease is thought be due to aberrant homing signal for the leukemic blasts precluding the more common bone marrow localization.[25] In recent years, there is an increase in reports of MS after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), manifesting as an EM relapse or bone marrow relapse, which may occur as a result of immune escape from the graft versus leukemic effect.[26] Moreover, there is increased likelihood that patients with EM relapse have had a preceding GVHD when compared to those with bone marrow relapse. Our patient developed EM relapse 6 months following ASCT and also had GVHD during the time of ASCT.

MS is more common in patients with AML with an incidence of 2.4–8%.[1,27,28] It is also reported in patients with a history of MDS and MPD and can represent leukemic transformation.[1] MS can occur concomitantly with, during the course or as a relapse of associated hematological malignancy, known as secondary MS. Rarely, MS can occur in nonleukemic patients, and bone marrow studies did not reveal any hematological malignancies known as primary/isolated MS/nonleukemic MS.[6] Most of these cases (primary MS), subsequently develop bone marrow involvement within a period of 1-year (median age being 5 months).[29] Following the diagnosis of MS, bone marrow studies are necessary to rule out hematological malignancies (primary MS) or know the status of the hematological disease (secondary MS) for the administration of appropriate treatment.[30]

A variety of chromosomal abnormalities are also reported in patients with AML with EM involvement, including translocation (t) (8,21), trisomy 8, inversion 16 and 11q23.[31] The information on chromosomal aberrations is limited and further investigational studies can help evaluating acute leukemia and its role in MS. In this review, two cases were reported to have cytogenetic abnormalities including inversion 16(p13;q22) and t (3,7) in one patient and duplication of the long arm of chromosome 11 in the other.[19,23]

MS is most commonly found in soft tissues, periosteum, bone, peritoneum, lymph nodes, and skin but can involve any organ of the body.[1] It is rarely reported in urogenital organs, with scattered case reports involving the kidney, prostate, urinary bladder, and gonads. To date, 19 cases of MS involving the prostate are reported in the literature.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] The present case is the first reported case of MS involving the periprostatic tissue. EM infiltration of the prostate is also reported in patients with lymphocytic leukemia and lymphomas and is limited to case reports. More cases are reported in the autopsy, with prostatic EML present at autopsy in up to 20% of patients with AML.[32] This disparity between clinical and autopsy incidence would imply the prostate is more frequently involved with EML than has been reported and that many cases may be asymptomatic and that the prostate may be a sanctuary site.[12]

MS can involve more than one tissue at the same time and in this review, one patient had MS involving the prostate, seminal vesicle, and bladder.[19] EM recurrences are also common either at the same location or at a different site. Thalhammer et al. described a case successfully treated MS of the prostate (chemotherapy), with a repeat prostate biopsy negative for leukemic cells; however, seven months later, the patient developed recurrent EM relapse in the prostate.[15] Presenting signs and symptoms are due to their local destructive or expansive properties and compression of nerves, the most common being pain and bleeding. The majority of patients with MS of the prostate present with typical obstructive urinary symptoms and are related to leukemic infiltration of the prostate and surrounding organs (bladder) or due to compression of neural structures.[11,27] The patients can also have elevated or fluctuating PSA levels and indurated prostate, thereby masquerading as prostate cancer.

The definitive diagnosis is made by tissue biopsy with the identification of myeloid precursor cells on immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and fluorescent in situ hybridization. Fine needle aspiration is not adequate, and tissue biopsy is the preferred method.[30] For an accurate diagnosis, multiple needle biopsies of the prostate should be taken when there is high suspicion of prostate involvement. MS consists of diffuse infiltration of myeloid or granulocytic cell components. The diagnosis of MS may be challenging, especially if the patient had no history of leukemia and can result in administration of inappropriate treatment.[1] In nearly half of the patients, it is misdiagnosed initially, the most common incorrect diagnosis being non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[33] The differential diagnosis is lengthy includes non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphoblastic leukemia, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, etc., some of which cannot be corrected until abnormal blood and bone marrow results are revealed.[34] Immunohistochemical staining is of great value in identifying antigens associated with myeloid lineage and assist in preventing any misdiagnosis. The commonly expressed myeloid markers include CD 68-KP1, MPO, lysozyme, CD2, CD 3, CD20, CD33, CD43, CD68, and CD117. CD68-KP1 (100%) is the most commonly expressed marker followed by MPO (83.6%).[31] In this review we found, MPO was positive in majority of these cases except for one case that stained negative for MPO,[19] however, the tumor cells were positive for other myeloid markers. None of the previously reported cases of MS of the prostate had associated prostate adenocarcinoma, and the present case is the first case of MS of the periprostatic tissue occurring concurrently with prostate adenocarcinoma. Guerrier and Persky reported a case of combined leukemic infiltration, hyperplasia, and carcinoma of the prostate in a patient with a history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[35] CT and magnetic resonance imaging can be used for tumor localization and differentiate it from hematoma and abscess.[36] Positive emission tomography-computed tomography is useful for monitoring the response following treatment of EM tumor.[30]

There is no optimal treatment for MS, systemic chemotherapy a regimen similar to that used to treat AML (remission induction chemotherapy) is the current recommended treatment.[25] Even in primary MS, AML-chemotherapeutic protocol is considered due to the high rate of progression to AML without systemic treatment. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant seems promising, and recent data suggest that chemotherapy combined with ASCT improve chances of survival, than chemotherapy used alone. However, its role is not clear if EM relapse occurred following treatment with ASCT. The incidence of MS after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation range from 0.2% to 1.3% and indicates treatment failure, with poor overall survival.[37,38] MS relapse following an ASCT is associated with marrow relapse in 20% of the patients.[39] If MS occurred after HSCT, donor lymphocyte infusion, tapering of immunosuppression, and radiation therapy (RT) options are considered.[6] Surgery and local radiation are considered to provide immediate symptomatic relief if it cause organ dysfunction or obstructive symptoms. MS is considered sensitive to RT and in a dose-dependent fashion.[40] Irradiation of prostate is considered superior to surgery (TURP/prostatectomy), due to complications of infection and hemorrhage from the later.[41] In this review (1997–2014), we found three patients received local radiation with relief of obstructive symptoms, and one of them had a negative repeat prostate biopsy for EML.[21,22,24] A review of literature of previous cases of MS of the prostate from 1940 to 1996, revealed two cases received local radiation of prostate[12,16] and one of them had a repeat prostate biopsy that was negative for EML.[12] Despite all the treatment options, MS is an indicator of poor prognosis, and it signals a blastic transformation in patients with MDS and MPD.[42] Overall median survival is 7–20 months after the diagnosis of MS.[29,43] Further prospective studies are needed to optimize treatment strategies and improve chances of survival in these patients. Expertise hematological consultation is needed in the management of MS, to avoid complications and improve chances of survival. The patients should be in a regular follow-up to confirm continued complete remission and reevaluate for the development of any EM or bone marrow relapse.

CONCLUSION

MS involving the prostate and other urogenital organs is extremely rare and are limited to case reports. MS should be considered as a differential diagnosis of prostate mass in patients with hematological cancers. The definitive diagnosis is made by tissue biopsy and multiple needle biopsies of the prostate are needed to increase the diagnostic yield. Local irradiation of prostate is considered superior to surgery to provide relief of symptoms and requires more prospective studies in order to generate treatment guidelines. Intensive chemotherapy, a regimen similar to AML is the standard treatment of underlying leukemia. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment strategies improve chances of survival and may delay progression to acute myeloid leukemia or blastic crisis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berard C, Bonner H, Mann R, Rydell RE, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1426–37. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810915)48:6<1426::aid-cncr2820480626>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns A. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Thomas Royce; 1811. Observations of Surgical Anatomy in Head and Neck. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King A. A case of chloroma. Mon J Med. 1853;17:97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rappaport H. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Sec. III, Fascicle 8. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1967. Tumors of the hematopoietic system. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: Rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yilmaz AF, Saydam G, Sahin F, Baran Y. Granulocytic sarcoma: A systematic review. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3:265–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaherty SA, Cope HE, Shecket HA. Prostatic obstruction as the presenting symptom of acute monocytic leukemia. J Urol. 1940;44:48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubin EN, Fetter TR, Erf LA. Subacute monocytic leukemia presenting symptoms of prostatism; a case report. J Urol. 1947;58:272–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)69555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tighe JR. Leukaemic infiltration of the prostate. Br J Surg. 1960;47:658–60. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004720613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitch WE, Jr, Serpick AA. Leukemic infiltration of the prostate: A reversible form of urinary obstruction. Cancer. 1970;26:1361–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197012)26:6<1361::aid-cncr2820260625>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muss HB, Moloney WC. Chloroma and other myeloblastic tumors. Blood. 1973;42:721–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belis JA, Lizza EF, Kim JC, Raich PC. Acute leukemic infiltration of the prostate. Successful treatment with radiation. Cancer. 1983;51:2164–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830615)51:12<2164::aid-cncr2820511203>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frame R, Head D, Lee R, Craven C, Ward JH. Granulocytic sarcoma of the prostate. Two cases causing urinary obstruction. Cancer. 1987;59:142–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870101)59:1<142::aid-cncr2820590128>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan YF. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) of the kidney and prostate. Br J Urol. 1990;65:655–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1990.tb14842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thalhammer F, Gisslinger H, Chott A, Haas O, Etele-Hainz A, Helbich T, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the prostate as the first manifestation of a late relapse of acute myelogenous leukemia. Ann Hematol. 1994;68:97–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01715141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quien ET, Wallach B, Sandhaus L, Kidd P, Strair R, Saidi P. Primary extramedullary leukemia of the prostate: Case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 1996;53:267–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199612)53:4<267::AID-AJH13>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope-Gill B, Goepel JR, Collin RC. Obstructive uropathy associated with myelomonocytic infiltration of the prostate. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:340–2. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smaoui S, Lecomte MJ, Peraldi R, Pernin F. Prostatic localization revealing an acute myeloid leukemia. Apropos of a case. Prog Urol. 1998;8:569–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spethmann S, Heuer R, Hopfer H, Tuinmann G. Myeloid sarcoma of the prostate as first clinical manifestation of acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:62–3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi A, Patel A, Patel K, Shah S, Shah P, Shukla SN, et al. Myeloid sarcoma of prostate with urinary obstruction: An unusual presentation of acute myelogenous leukemia in a child. Indian J Med Pediatr Oncol. 2005;26:40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson GA, Braaten K. Prostatic extramedullary leukemia as a first site of relapse of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:419–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuboi K, Kawada H, Suzuki R, Murayama H, Ohmachi K, Nakamura N, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the prostate presenting with urinary obstruction which progressed to acute myeloid leukemia. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2008;49:1562–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mneimneh WS, Bonte H, Bernheim A, Martin A. Myeloid sarcoma of the prostate revealed by urinary retention: A case report. BMJ Case Rep 2009. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0240. pii: Bcr0620080240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nitta M, Hoshi A, Shinozaki T, Soeda S, Kawakami M, Kin H, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the prostate. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2010;56:521–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: Current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol. 2011;2:309–16. doi: 10.1177/2040620711410774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolb HJ. Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood. 2008;112:4371–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu PI, Ishimaru T, McGregor DH, Okada H, Steer A. Autopsy study of granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) in patients with myelogenous leukemia, Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1949-1969. Cancer. 1973;31:948–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197304)31:4<948::aid-cncr2820310428>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiernik PH, Serpick AA. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) Blood. 1970;35:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breccia M, Mandelli F, Petti MC, D’Andrea M, Pescarmona E, Pileri SA, et al. Clinico-pathological characteristics of myeloid sarcoma at diagnosis and during follow-up: Report of 12 cases from a single institution. Leuk Res. 2004;28:1165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pileri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, Campidelli C, Bacci F, Piccioli M, et al. Myeloid sarcoma: Clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia. 2007;21:340–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viadana E, Bross ID, Pickren JW. An autopsy study of the metastatic patterns of human leukemias. Oncology. 1978;35:87–96. doi: 10.1159/000225262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meis JM, Butler JJ, Osborne BM, Manning JT. Granulocytic sarcoma in nonleukemic patients. Cancer. 1986;58:2697–709. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861215)58:12<2697::aid-cncr2820581225>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamauchi K, Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma: Report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the literature. Cancer. 2002;94:1739–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerrier KR, Persky L. Combined leukemia, carcinoma, and hyperplasia of the prostate. Arch Surg. 1969;98:365–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340090141026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pui MH, Fletcher BD, Langston JW. Granulocytic sarcoma in childhood leukemia: Imaging features. Radiology. 1994;190:698–702. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.3.8115614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szomor A, Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Hoffmann T, Speck B, Gratwohl A. Myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome relapsing as granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Ann Hematol. 1997;75:239–41. doi: 10.1007/s002770050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Békássy AN, Hermans J, Gorin NC, Gratwohl A. Granulocytic sarcoma after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: A retrospective European multicenter survey. Acute and chronic leukemia working parties of the European group for blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:801–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ, Dawson NA. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: A clinical review. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1800–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chak LY, Sapozink MD, Cox RS. Extramedullary lesions in non-lymphocytic leukemia: Results of radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1173–6. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(83)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rader ES. Leukemic infiltration of prostate. Urology. 1974;3:779–81. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(74)80226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paydas S, Zorludemir S, Ergin M. Granulocytic sarcoma: 32 cases and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2527–41. doi: 10.1080/10428190600967196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Estey E, Cortes JE, Verstovsek S, Faderl S, et al. Outcome in patients with nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma treated with chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. Leukemia. 2003;17:1100–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]