Abstract

MHC glycoproteins form supramolecular clusters with interleukin-2 and -15 receptors in lipid rafts of T cells. The role of highly expressed MHC I in maintaining these clusters is unknown. We knocked down MHC I in FT7.10 human T cells, and studied protein clustering at two hierarchic levels: molecular aggregations and mobility by Förster resonance energy transfer and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy; and segregation into larger domains or superclusters by superresolution stimulated emission depletion microscopy. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy-based molecular brightness analysis revealed that the studied molecules diffused as tight aggregates of several proteins of a kind. Knockdown reduced the number of MHC I containing molecular aggregates and their average MHC I content, and decreased the heteroassociation of MHC I with IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα. The mobility of not only MHC I but also that of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα increased, corroborating the general size decrease of tight aggregates. A multifaceted analysis of stimulated emission depletion images revealed that the diameter of MHC I superclusters diminished from 400–600 to 200–300 nm, whereas those of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα hardly changed. MHC I and IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα colocalized with GM1 ganglioside-rich lipid rafts, but MHC I clusters retracted to smaller subsets of GM1- and IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα-rich areas upon knockdown. Our results prove that changes in expression level may significantly alter the organization and mobility of interacting membrane proteins.

Introduction

Membrane receptors perform their roles in functional complexes, where some elements participate in signaling directly, others act as regulators, and the function of certain other elements is as-yet undefined. Earlier we have shown that MHC I and II were associated with IL-2R and IL-15R, and these proteins formed supramolecular clusters in lipid rafts (membrane domains rich in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids) of T cells (1, 2). However, the role of the highly expressed MHC glycoproteins in these complexes has not been elucidated. In this article we examined how the assembly, interactions, and mobility of IL-2 and -15 receptors are influenced by MHC I in T lymphoma cells.

MHC I is a heterodimer consisting of a transmembrane heavy chain and an extracellular light chain, i.e., the beta-2 microglobulin (β2m), which has no transmembrane domain. MHC I is expressed in most nucleated cells, where it presents self or viral antigens to T cell receptors expressed by CD8+ T cells, initiating T cell activation upon antigen recognition (3). MHC I can form oligomers as indicated by Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and electron microscopy data from immunogold-labeled B and T cells (4, 5, 6, 7). In addition to IL-2Rα (8, 9) and IL-15Rα (1), it can also associate with a series of different membrane proteins including receptors in various cell types: IL-9Rα on T lymphoma cells (10), MHC II on B lymphoma cells (11), EGF receptors in human fibroblasts and A431 cells (12), ICAM-1 on T and B lymphoma, uveal melanoma, and colon carcinoma cells (4, 8, 9, 13, 14), insulin receptors on B lymphoblasts (15, 16) and fibroblasts (17), tetraspan molecules on B lymphoblasts (18), and transferrin receptors on T lymphoma cells (13, 19). Through its interactions with receptors, MHC I may interfere with signaling processes, such as in the case of the insulin receptor (20, 21). MHC I can mediate transmembrane signaling (22), and antibody binding to the light chain may induce apoptosis via the PI-3 kinase pathway (23). Thus, over the decades a multifaceted view of MHC I has been emerging—one that goes beyond its classical antigen-presenting function (see reviews, e.g., in Arosa et al. (24) and Bowness et al. (25)).

The cytokines IL-2 and -15 play important roles in the activation, proliferation, death, and survival of immune cells (26, 27). Their receptors are built of three subunits, two of which, the β- and γc-chains, are shared by the two cytokines. We have shown by FRET that IL-2 (28) and IL-15 receptors were preassembled on lymphoma/leukemia cells (1), and that they could form a heterotetrameric complex composed of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and the β- and γc-chains (1). The β- and γc-subunits are the starting points of several signaling processes including the JAK/STAT pathway (27, 29, 30, 31). Because they share the same signaling receptor chains, IL-2 and IL-15 also have several functions in common: they promote the proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes and augment the cytotoxicity of T and NK cells in vitro (26, 32). However, they may also play opposing roles in T cells: IL-2 induces apoptosis in activation-induced cell death, whereas IL-15 preferentially promotes the survival of CD8+ memory T cells and inhibits apoptosis (32, 33). This divergence of cell fates is not fully understood. It may be caused by different interactions of the α-subunits with other signaling molecules or membrane proteins. Therefore, clustering and interactions of IL-2 and -15 receptors with surrounding membrane components is an important issue to investigate.

The first pieces of evidence for the close molecular proximity of MHC I and IL-2Rα were obtained from FRET experiments on a T lymphoma cell line (34) and later on activated peripheral T cells (35). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching showed the slowing-down of IL-2Rα diffusion after ligating MHC I with an antibody (36). Transmission electron microscopy analysis indicated that the two molecules were partially co-clustered in Kit 225 K6 T lymphoma cells (37). Our FRET studies on Kit 225 FT7.10 T lymphoma cells overexpressing IL-15Rα revealed the close molecular proximity of IL-2Rα/IL15Rα subunits and MHC I/MHC II molecules in lipid rafts (1). Using fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy, we have also proven that IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I stably codiffused in the plasma membrane (1).

To unravel the possible role of MHC I in clustering of IL-2/IL-15 receptors, we knocked down MHC I expression at the cell surface. We used siRNA against β2m, because the transport of the MHC I heavy chain to the cell surface is impaired in the absence of the light chain (38). FRET was applied to investigate changes of protein-protein interactions at the nanometer scale, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) was used to assess protein mobility and homoaggregation state, and confocal microscopy was applied to analyze compartmentation in lipid rafts. The size of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I protein clusters and the extent of co-clustering at 40-nm resolution were determined by combining stimulated emission depletion (STED) superresolution microscopy with image analysis methods.

Materials and Methods

Cells

FT7.10 is a CD4+, IL-2-dependent human adult T lymphoma cell line derived from Kit 225 cells (39). It expresses all three subunits of IL-2R constitutively, and is stably transfected with IL-15Rα carrying an N-terminal FLAG-tag. Cell culturing and fluorescence labeling of cells with monoclonal antibodies is described in the Supporting Material.

RNA interference

While the heavy chain of MHC I has A, B, and C alleles with many sequence variants each, the sequence of the light chain (β2m) is conserved. Association with β2m is indispensable for MHC I to reach the cell surface (40), thus, we knocked down β2m. Absolute numbers of MHC I, MHC II, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα molecules per cell were estimated by flow cytometry using QIFIKIT beads (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA; Figs. 1 and S1). For details on these procedures, see the Supporting Material.

Figure 1.

Protein expression in control and MHC I knockdown cells determined by flow cytometry. Quantification of IL-2Rα molecules per cell was performed by using QIFIKIT beads (Dako North America). Expression of MHC I, MHC II, and IL-15Rα proteins was assessed by comparing the mean fluorescence intensities of directly labeled epitopes (targeted by Alexa 546-tagged W6/32, L243, and anti-FLAG mAbs) to that of directly labeled IL-2Rα (Alexa 546-anti-Tac mAb). Fluorescence intensities were normalized by the dye/protein antibody labeling ratios determined by absorption photometry. Error bars are SD values of averages of triplicate samples (n ∼ 104 cells per sample).

FCS

To measure diffusion properties of membrane proteins, we used FCS (41, 42). The FCS microscope is described in Beck et al. (43) and Mocsár et al. (44). Autocorrelation curves were fitted to a model assuming lateral diffusion of a single component and triplet state formation. The lateral e−2 radius of the detection volume was calibrated with a solution of Alexa 488 having a known diffusion coefficient (45). Correlation curves were fitted by using the QuickFit 3.0 software (46). Molecular brightness (photon count rate per molecule) was calculated as the ratio of the average, background-corrected fluorescence count rate, F, and the mean (background-corrected) number of molecules, N, in the detection volume. This parameter gives an estimate of the number of fluorescent molecules in a jointly moving complex if normalized with the F/N of freely diffusing Fab fragments. The expression levels of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα in the subpopulation sampled by FCS were similar to those measured by flow cytometry (Fig. S1). Bleached fractions of proteins were assessed from count traces of FCS measurements. Further details on FCS are given in the Supporting Material.

Confocal microscopic colocalization

Colocalization of membrane proteins with lipid raft markers at the few-hundred-nm scale was determined from confocal images of doubly labeled cells by confocal microscopy. Colocalization was assessed by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the pixel intensities of the two detection channels as described in Vereb et al. (37). Further details are given in the Supporting Material.

Determination of FRET efficiency by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy

Molecular proximity between proteins was detected by Förster resonance energy transfer. Cells were doubly labeled with mAbs tagged with donor (Alexa 546) or acceptor (Alexa 647) dyes. Flow cytometric FRET measurements were carried out on a FACSAria III instrument (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and analyzed as described in Sebestyén et al. (47) and Szentesi et al. (48). Acceptor photobleaching FRET measurements were carried out and analyzed on a pixel-by-pixel basis as described earlier in Vámosi et al. (1) and Nizsaloczki et al. (10). For details, see the Supporting Material.

STED microscopy

Two-color superresolution image acquisition was carried out using a custom-built STED microscope described in Wildanger et al. (49), Bückers et al. (50), and Rönnlund et al. (51). Before STED imaging, regular confocal images were also recorded by the microscope. The resolution of the system in STED mode was ∼40 nm for both colors (52). The distance between two neighboring pixels was 20 nm for STED and 50 nm for confocal images; the image size was 15 × 15 μm2. For excitation 570 ± 5 and 647 nm, STED beams 710 ± 10- and 750 ± 10-nm wavelengths were used. Fluorescence emissions were collected at 615 ± 15 and 675 ± 15 nm for the Alexa-594 and ATTO-647N dyes.

Estimating the size of protein clusters from analysis of STED images

The sizes of IL-2/15R and MHC I protein clusters in control and MHC I knockdown (MHC I KD) cells were determined by using three different methods.

Full-width at half-maximum method

In the first procedure, the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) values of the intensity peaks detected on the cell surface were measured. Before image analysis, all images were deconvolved using 20 iterations of the Richardson-Lucy algorithm (51) and assuming a 40-nm wide Lorentzian-shaped point spread function (PSF). The size of each peak was calculated as the mean FWHM value measured over 20 different angles.

Spatial correlation function method

In the second procedure, the spatial correlation curves of superresolution images of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα were calculated. Empirical curves were fitted with a model function, which allowed estimation of the average cluster diameter (53, 54). Spatial correlation can be defined as follows:

| (1) |

where is the fluorescence intensity at position r, and brackets denote averaging over positions . Then the spatial correlation function was calculated with the following formula:

| (2) |

where is the intensity of the (i,j)th pixel in the region of interest, r is the distance between two pixels in the calculation of correlation, and N(r) is the number of pixels that are r pixels apart. If multiple molecular clusters are present, the total correlation function can be broken down into three terms:

| (3) |

The first term (GPSF) describes the shape of the correlation function of the PSF, whereas the other two terms describe the pair correlation of particles within and between clusters. To fit empirical correlation functions and estimate cluster sizes, we used the sum of three Gaussians:

| (4) |

where w is the lateral radius of the effective PSF, parameter d was interpreted as a quantity proportional to the average radius of clusters, and g is the average separation distance between clusters. (Coefficient ρ1 is proportional to the number of fluorophores, ρ2 to the number of particle pairs within a cluster, and ρ3 to the number of particle pairs from different clusters.) The formula was tested by computer simulations.

Cluster segmentation method

The third procedure, the cluster segmentation method (55), is based on the classification of pixels of STED images of cell surface protein distributions. Regions of interest were constructed for each cell, then images were intensity-thresholded and pixels above the threshold were selected. The threshold was set halfway between the background and the average of the half-maximal intensities of fluorescent peaks for each channel. A pixel cluster is defined as a contiguous region of neighboring pixels above the threshold. The number of pixels (characterizing cluster size) and the total intensity within the clusters (measuring protein content) were collected for all clusters and both channels. Applying this segmentation algorithm to dual-color images allowed the identification of either common or unique clusters of IL-2Rα or IL-15Rα and MHC I. Data were presented as probability density histograms. For statistical comparisons, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. To characterize the distribution of protein content within clusters, the total intensities of the clusters were calculated and plotted as a function of cluster size.

Calculation of molecular fractions

Fractions of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα in common clusters with MHC I were calculated by dividing the total intensity from receptor subunits in common clusters with MHC I by the total intensity of receptor subunits in the whole region of interest, e.g.:

| (5) |

where is the intensity of a pixel of IL-2Rα measured in the red channel. Summation in the numerator includes double positive pixels, where both the IL-2Rα (red) and MHC I (green) signals are above the threshold, whereas the denominator includes all pixels where the IL-2Rα signal is above the threshold. Molecular colocalization was also assessed by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the pixel intensities of the two detection channels. Associated fractions and Pearson’s coefficients were plotted as bar diagrams. Image analysis methods and fitting routines were implemented in custom-written MATLAB scripts (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Results

Expression of IL-2/15R and MHC glycoproteins before and after MHC I knockdown

IL-2R, IL-15R, MHC I, and MHC II form superclusters in lipid rafts of Kit 225 FT7.10 T lymphoma cells. To define the role of the most abundant element, MHC I, in the organization of these clusters, we knocked down MHC I expression by anti-β2m siRNA. Fig. 1 shows the number of antibody binding sites per cell for each molecular species before and after KD; histograms of expression distributions are presented in Fig. S1. Because of the high abundance of MHC I, it was essential to maximize silencing efficiency. MHC I expression at the cell surface decreased with increasing siRNA concentration, reaching a maximal effect at 100 μg/mL where expression was reduced to 5–10%. KD was specific: expression levels of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, or MHC II did not change. Irrelevant siRNA (anti-GFP or anti-erbB1) used as control caused no variation in the expression of MHC I, IL-2Rα, or IL-15Rα.

Increased mobility of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I upon MHC I KD

We were interested how the expression level of MHC I at the cell surface affects the dynamic properties and organization of the elements of the superclusters, including those of MHC I itself. We assessed the location of cells measured by FCS in the expression range of the total cell population to make sure that the sample represents the whole population well. Fig. S1 shows the histograms of the expression distributions of the total cell population determined by flow cytometry, and those of the FCS-sampled population as overlaid box-and-whiskers plots (converted to number of receptors in the confocal spot). The good overlap between the graphs proves that cells picked for FCS measurements had similar protein expression distributions as the original population measured by flow cytometry.

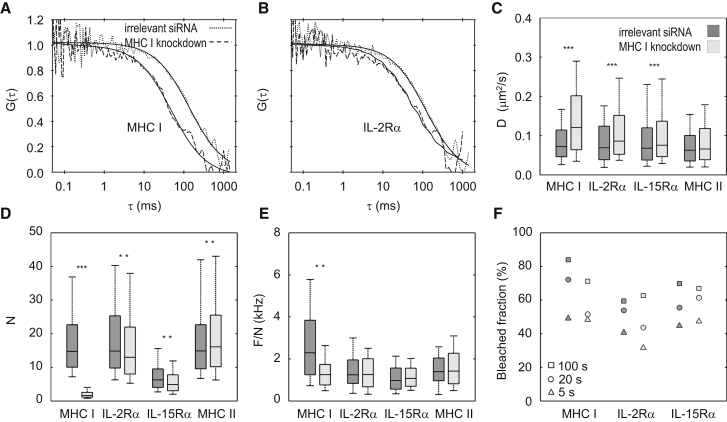

If a protein is in a jointly moving cluster/aggregate, its mobility in the membrane is inversely related to the size of the aggregate. To assess changes of mobility, the lateral diffusion coefficients of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, MHC I, and MHC II were determined by FCS. Fig. 2, A and B, shows representative autocorrelation functions (ACFs); in Fig. S2, raw intensity traces and ACFs of individual runs, fits, and residuals are presented. Upon MHC I KD, ACFs shifted toward shorter diffusion times, indicating an increase of mobility (Fig. 2, A and B). Diffusion coefficients (D) increased significantly for IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα (p < 0.001), and MHC I (p < 0.01). Conversely, we detected no statistically significant change for MHC II (Fig. 2 C). We separately analyzed diffusion coefficients of MHC I and IL-2Rα residing in large patches and outside patches. The mobility of these proteins was lower inside patches than outside them (Fig. S4). The value D decreased with increasing expression density (increasing local F) of MHC I, in line with the observed increasing tendency of D upon KD (Fig. S5, A and B).

Figure 2.

FCS analysis of molecular mobility, concentration (N), aggregation (molecular brightness), and bleached fraction upon MHC I knockdown. (A and B) Normalized autocorrelation functions of MHC I and IL-2Rα. (C) Average diffusion coefficients. (D) Average particle numbers in the FCS detection volume. (E) Specific molecular brightness, F/N, normalized by the F/N values of Fab fragments in solution. (F) Median bleached fractions of molecules calculated from the intensities after 5, 20, and 100 s (after the first, fourth, and 20th runs) of the 100-s illumination period. The following Alexa 488-conjugated Fab fragments were used for labeling: W6/32 for MHC I, anti-Tac for IL-2Rα, anti-FLAG for IL-15Rα, and L243 for MHC II. Distributions were compared with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.1; boxes represent 25 and 75%; whiskers, 10 and 90%. n = 25–35 cells per sample.

Decreased molecular brightness of MHC I indicates reduction of protein aggregate size

The mean number of molecules in the detection volume (N) is a measure of the local concentration of diffusing particles (single molecules or aggregates), whereas the molecular brightness (the fluorescence intensity per particle, F/N, measured in photon counts per second per particle) is proportional to the number of labeled proteins forming an aggregate. To assess changes in the number and size of aggregates, we measured these parameters before and after MHC I KD. For MHC I, the average value of N decreased 10-fold (Fig. 2 D, p < 0.001). We found a strong positive correlation between the expression density of MHC I and the number of aggregates (Fig. S5, C and D), corroborating the result of KD. In contrast, the N values for IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC II were not largely affected by MHC I KD; small variations of N might be due to variations in the expression levels of the randomly selected cells.

To calibrate F/N as a measure of the degree homoaggregation (number of proteins of interest in the aggregate), we first measured the brightness of the fluorescent Fab fragments freely diffusing in buffer solution, which yields the brightness of a single Fab. Next, we measured F/N values of Fab-s bound to their target proteins in the cell membrane, and normalized them by the F/N values measured in solution (Fig. 2 E). On control cells, the median normalized F/N values were ∼2.3 for MHC I, 1.3 for IL-2Rα, 1.0 for IL-15Rα, and 1.3 for MHC II, suggesting protein aggregation. Because the dye/protein labeling ratios (D/p) of the Fab fragments were <1 (see the Supporting Material), these numbers may underestimate the extent of aggregation. MHC I KD caused a 40% reduction of the median specific brightness of MHC I (p < 0.001), indicating that the number of MHC I molecules jointly diffusing in a cluster decreased significantly. The brightness of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC II showed only a slight decrease, which was statistically not significant. For MHC I, the dependence of the specific brightness had an increasing tendency with increasing local expression density (Fig. S5, E and F), in line with our observations upon MHC I KD.

Finally, bleached fractions of molecules were estimated from intensity traces (Fig. S2) of FCS experiments. Bleached fractions were calculated after 5, 20, and 100 s of illumination (Fig. 2 F). After 20 s of illumination, the fraction of bleached proteins was in the range of 50–70%. For MHC I, the bleached fractions decreased upon KD, corroborating the overall increase of mobility.

FRET implies partial disassembly of MHC I/IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα clusters upon MHC I KD: decrease of the extent of homo- and heteroassociations of MHC I

To dissect interactions between individual protein species at the nanometer scale, we applied FRET. Homo- and heteroassociations of IL-2R and IL-15R subunits, MHC I and II glycoproteins, were analyzed on a cell-by-cell basis using flow cytometry (Fig. 3 A), or on a pixel-by-pixel basis with the acceptor photobleaching technique using confocal microscopy (Fig. 3 B). As a negative control, the FRET efficiency between coated-pit-located transferrin receptors and lipid-raft-located GPI-anchored CD48 proteins was measured, yielding E = 3 ± 1%. As positive control, we measured FRET between the light and heavy chains of MHC I, which decreased from 52 ± 1% to 28 ± 1% upon MHC I KD. Here, the FRET process is only partially intramolecular: FRET can also occur between the light and heavy chains of distinct MHC I molecules residing next to each other in an aggregate. Thus, the decrease of FRET efficiency suggests diminishing of MHC I homoassociation. We measured homoclustering of MHC I heavy chains, which decreased significantly upon MHC I knockdown: the FRET efficiency dropped from 35 ± 1% to 11 ± 1% (Fig. 3 A). Here, MHC I was targeted using donor- and acceptor-tagged antibodies specific for the heavy chain of intact MHC I, containing both β2m and the heavy chain. The heteroassociation of donor-labeled IL-2Rα and acceptor-labeled MHC I also decreased significantly upon MHC I KD, from 47 ± 1% to 9 ± 1%. FRET between IL-15Rα and MHC I decreased similarly, from 44 ± 1% to 7 ± 1%. This is not surprising because the acceptor/donor ratio decreased, thereby the probability that a given donor-labeled protein had an acceptor-labeled partner within FRET-range (2–10 nm), diminished. The heteroassociation of IL-15Rα with IL-2Rα, or IL-2Rβ with IL-2Rα did not change significantly, suggesting that interleukin receptor assembly was not influenced by interactions with MHC I. We also analyzed FRET efficiencies as a function of expression levels of the interacting proteins shown in Fig. S6. Cells were classified into three classes according to the expression (i.e., low, medium, high) of the donor-tagged proteins. For the heteroassociation of donor-tagged IL-15Rα or IL-2Rα with acceptor-tagged MHC I, there is a clear tendency of increasing FRET efficiency versus increasing NA/ND acceptor/donor molecular ratio, and a faster saturation of the graph for higher donor expressors, just as expected for association equilibria. For MHC I homoassociation, the FRET efficiency increases with an increasing expression level of MHC I as expected.

Figure 3.

FRET analysis of the effect of MHC I knockdown on molecular proximities. (A) Means of average FRET efficiencies of duplicate flow cytometric measurements (N > 10,000 cells) between IL-2/15Rα subunits and MHC I. Proteins were labeled with different pairs of donor (Alexa 546)- and acceptor (Alexa 647)-tagged antibodies (IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I were labeled with Alexa 546-anti-Tac, Alexa 546-7A4 24. and Alexa 647-W6/32 mAbs). Positive control: FRET between the light chain (β2m, labeled with Alexa546-L368) and heavy chain of MHC I. Negative control: transferrin receptor (TfR, located in coated pits, labeled with Alexa 546-MEM75 mAb) and GPI-anchored CD48 (enriched in lipid rafts, targeted by Alexa647-MEM102 mAb). Error bars are SD values. (B) Distribution of pixelwise FRET efficiencies between IL-2Rβ + IL-2Rα measured by the acceptor photobleaching method using confocal microscopy (n > 25 cells per sample; IL-2Rβ and IL-2Rα were labeled with Alexa 546-Mikβ3 and Alexa 647-7G7-B6). Mean FRET efficiency values were 9 and 10% in control and KD cells. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde.

Analysis of STED images shows a reduction of MHC I protein supercluster size upon KD

Our FCS and FRET data suggested that the size of small-scale protein aggregates diminished upon MHC I KD. We used superresolution STED microscopy to get a direct insight into the effect of MHC I KD on the higher-order clustering of the studied proteins. STED (Figs. 4 and S7) and confocal images (Fig. S8) of the (co)distributions of the fluorescently labeled proteins were taken in KD and control cells. The optical resolution of the STED microscope was ∼40 nm, and the pixel size was 20 nm. To estimate the size of protein superclusters, we used three different image analysis methods (Fig. 5, A1–C1).

Figure 4.

Two-color STED images of cell surface protein codistributions on FT7.10 T lymphoma cells. (A) MHC I and IL-2Rα and (B) MHC I and IL-15Rα. MHC I was labeled with Alexa 594-W6/32 mAb (green, top row), IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα with ATTO 647N-anti-Tac and ATTO 647N-anti-FLAG mAbs (red, middle row), and fixed with formaldehyde. In the overlay images (bottom row), the yellow color shows the overlapping regions of MHC I and IL-R distributions. Because of the large differences in gray values between raw intensity data of MHC knockdown and control samples, intensities were rescaled. (Yellow squares) Areas displayed in the high-magnification images next to the low-magnification image. Scale bar in the low- and high-magnification images represent 7 μm and 0.7 μm, respectively.

Figure 5.

Cluster-size distributions of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα determined from STED microscopy images. The schemes in the top row illustrate the calculation of each parameter shown below. (A) Effect of MHC I knockdown (KD) on cluster size determined from Gaussian fits to intensity peaks in STED images. Pixel size is 20 nm. (A1) Direction-averaged FWHM of intensity peaks. Each peak represents a receptor cluster (see Materials and Methods); FWHM values are measures of average cluster size. (A2–A4) Histograms display the probability distributions of peak widths of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα clusters in control and MHC I knockdown cells. (A5) Mean values of FWHMs. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0005, ∗p < 0.05 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), n = 10–15 cells per sample. (B) Spatial autocorrelation analysis of protein cluster sizes. (B1) Scheme of calculating radial autocorrelation functions for radii of 1–100 pixels. (B2–B4) Average radial autocorrelation functions of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα in control and MHC KD cells. Radii were measured in pixels. (B5) Estimated mean cluster sizes of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα based on a triexponential fit of the correlation curves. The shortest correlation radius is related to the PSF; the medium one (shown in the figure) corresponds to the average cluster size; and the largest one probably to intercluster distances. ∗p < 0.05 (unpaired t-test). (C) Image segmentation analysis of protein clusters. (C1) Images were intensity-thresholded and the number of pixels in contiguous clusters was determined. (C2–C4) Probability distributions of cluster areas (number of pixels in contiguous areas above threshold) in control or MHC I KD cells. (C5) Mean values of cluster areas. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0005 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). (D) Analysis of relative protein content of clusters. (D1) Total fluorescence intensities of clusters defined in (C) were calculated and sorted according to cluster size. (D2–D4) Histograms represent probability distributions of protein content versus cluster area. (D5) Most populated cluster sizes for MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0005 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

First, the FWHM values of intensity peaks of STED images were calculated in control and MHC I KD cells. The concept of the method is shown in Fig. 5 A1. The distributions of the FWHM of peaks are depicted in Fig. 5, A2–A4. Interestingly, the mean diameter of MHC I clusters decreased starkly after KD, from 640 ± 120 nm to 260 ± 80 nm (31 ± 6 to 13 ± 4 pixels, mean ± SE, p < 0.0005). In contrast, the average size of IL-2Rα clusters did not change significantly, and the FWHM of IL-15Rα peaks decreased only slightly from 360 ± 60 nm to 300 ± 60 nm (18 ± 3 to 15 ± 3 pixels, p < 0.05; Fig. 5 A5).

Second, we applied spatial correlation analysis of intensity distributions to assess cluster sizes (Fig. 5, B1–B5). The angle-averaged radial correlation functions of fluorescence images were calculated according to Eq. 2 (see schematic drawing in Fig. 5 B1). Fig. 5, B2–B4, shows average radial correlation curves of protein distributions in cells after MHC I KD and for controls. Correlation curves were fitted to a triple exponential model function, where the first term is assigned to the PSF, the second one to the mean diameter of clusters on the cell surface, and the third one to intercluster distances. This analysis confirmed the impact of KD on cluster sizes: the mean radius of MHC I clusters (correlation length of the second term) was reduced from 340 ± 120 nm to 200 ± 120 nm (17 ± 2 to 10 ± 2 pixels, means ± SE) after MHC I KD. The average radii of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα clusters were in the range of 280–320 nm (14–16 pixels), and did not change significantly (Fig. 5 B5). The third component of the correlation function was well separable from the second one; its characteristic radius was in the range of 1.04–1.32 μm (52–66 pixels) for all the studied proteins.

Third, we measured the mean occupied areas of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα clusters by an image segmentation method (see Fig. 5 C1 for scheme). The previous methods estimate the average diameter of clusters, whereas this procedure assesses the area of contiguous high-intensity pixels. The probability distributions of above-threshold contiguous areas are shown in Fig. 5, C2–C4. The mean area of MHC I clusters decreased significantly upon KD (p > 0.0005) from (7.2 ± 0.9) × 104 nm2 to (1.8 ± 0.2) × 104 nm2 (181 ± 23 to 44 ± 5 pixels, mean ± SE). The areas occupied by interleukin receptors did not change significantly (Fig. 5 C5). It is interesting to note that the area occupied by MHC I and IL-2Rα in control cells was approximately twice the area occupied by IL-15Rα.

The use of superresolution microscopy made it possible to investigate the decrease of MHC I cluster size; confocal imaging could not resolve changes at this length scale. Taking together the results of the three distinct analysis methods of the STED images, a significant reduction of occupied areas and diameters of MHC I clusters was observed upon MHC I KD, whereas the cluster sizes of IL-2 and -15 receptors changed only slightly. Thus, changes seen by molecular brightness analysis and FRET at the scale of small molecular aggregates were paralleled by similar changes at the scale of submicrometer-sized superclusters.

The previous analyses dealt with the spatial dimensions of large protein clusters, but not with their protein content, which also depends on the density of proteins in the clusters. To quantify the amount of receptors in clusters of different sizes, the summed fluorescence intensities of clusters of a given size were calculated. Intensities were normalized to the total intensity of all clusters. The relative protein content of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα clusters versus cluster size are shown in Fig. 5, D2–D5, for control and KD cells. The most populated cluster size of MHC I decreased from (10 ± 0.4) × 104 nm2 to (3.2 ± 0.1) × 104 nm2 (2500 ± 100 to 800 ± 30 pixels, mean ± SE) after KD. The most preferred cluster sizes of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα receptors did not change significantly (Fig. 5 D5).

Colocalized fraction of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα with MHC I is reduced upon MHC I KD

FRET analysis of molecular interactions at the 2–10-nm scale showed that heteroassociations of MHC I with IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα diminished when the MHC I content of the cell membrane decreased. To assess changes of colocalization with a resolution of 40 nm, molecular fractions of colocalized proteins were calculated from STED images (Fig. 6 A).

Figure 6.

Colocalization analysis of MHC I with IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα in STED images. (A) Fractions of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα molecules residing in common clusters with MHC I (and vice versa) derived from STED images of doubly labeled samples (referred to, e.g., as IL-2Rα near MHC I). (B) Pearson’s correlation coefficients of MHC I-IL-2Rα and MHC I-IL-15Rα codistributions from STED images (n = 10–15 cells per sample). Samples were compared with two-tailed t-tests, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Our first observation is that in control cells, the fractions of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα in the vicinity of MHC I, as well as the fraction of MHC I in the vicinity of IL-2Rα, are high, as opposed to the scarcity of MHC I near IL-15Rα, which may be due to the lower expression level of IL-15Rα. Remarkably, the mutual vicinities of MHC I and interleukin receptors showed an asymmetric behavior after MHC I KD. The fraction of IL-2Rα found near MHC I in STED images was reduced from 75 ± 3% (control) to 5.4 ± 3% (KD). Similarly, the proportion of IL-15Rα near MHC I was significantly reduced, from 91 ± 4% to 20 ± 6% (Fig. 6 A). Conversely, the fraction of MHC I colocalized with IL-2Rα decreased only slightly, from 61 ± 8% to 52 ± 7%, and its fraction near IL-15Rα even increased from 12 ± 2% to 19 ± 5% upon KD (Fig. 6 A). MHC I molecules probably retracted to a smaller total area, but remained in the vicinity of interleukin receptors, suggesting that their association with IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα was stable.

Colocalization between MHC I and IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα subunits was also analyzed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients (C) of their pixelwise intensity distributions. We calculated C values with three thresholding conditions: for pixels where the intensity in one, the other, or both channels was above the threshold (Fig. 6 B). The C values were significantly reduced for both pairs (MHC I + IL-2Rα as well as MHC I + IL-15Rα) upon KD of MHC I. Our results on Pearson’s correlation coefficients are in line with the findings that, after KD, the majority of interleukin receptors were situated in clusters free of MHC I. As a negative control, pixels within both images were randomly mixed (>10,000 iterations), thereby making the intensity distributions in the two channels independent of one another. Correlation coefficients were calculated for these randomized images, resulting in C values of 0.007 ± 0.0001 (SD) for STED images. We applied the same analyses to confocal images acquired from the same cells, and found similar tendencies; however, numerical values of colocalized fractions and Pearson’s coefficients were different due to the inability of confocal microscopy to resolve finer details (see Fig. S8).

To better understand our results, we carried out simulations to model the effect of KD on the value of C. In one channel the expression density was set to 0.2 particle/pixel, corresponding to the density of IL-2Rα derived from flow cytometry (Fig. S9, right column). In the other channel (left column), the particle density was reduced from 0.8 particle/pixel (our estimate for MHC I in control cells) to 0.05 particle/pixel (the value after KD), while the fraction of particles participating in co-clusters was set to 20% throughout. Decreasing the number of MHC I particles resulted in a decrease of C from 0.8 to 0.5, showing that the experimentally observed decrease of C could partially be explained by the change of the S/N upon KD, even though the extent of co-clustering was maintained.

Membrane microdomain localization of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα subunits remains unchanged upon MHC I knockdown

Earlier studies found that IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I molecules were enriched in lipid rafts of Kit 225 cells (1, 13, 37). The signaling efficiency of IL-2Rα was shown to depend on the cholesterol content of the membrane and the integrity of lipid rafts (13). We were interested in whether knocking down MHC I affects the localization of IL-receptors with respect to lipid raft domains. Codistributions of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, or MHC I with the lipid raft marker GM1 ganglioside were recorded by confocal microscopy (Fig. S10) followed by intensity correlation analysis. The distribution of both receptor subunits and MHC I displayed a substantial overlap with GM1 in control (mock-transfected) and MHC I KD cells as indicated by the yellow regions in the overlay images. Correlation coefficients of the images of the receptor subunits and GM1 did not change significantly upon gene silencing (Fig. S10 D). These results imply that the enrichment of IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα in lipid rafts does not depend on the presence or absence of MHC I. On the other hand, the C values between MHC I and GM1 decreased from 0.4 ± 0.1 to 0.28 ± 0.08 (mean ± SD), which may be explained by our simulations (see Fig. S9).

Discussion

Membrane proteins form dynamic clusters at different hierarchical levels (56, 57), which may be regulated by several factors. These include protein-protein interactions between transmembrane helices or extra/intracellular domains, the lipid composition of the membrane, the cytoskeleton, or cross-linking of glycoproteins by galectin lattices (58, 59). In T cells, disruption of lipid rafts by cholesterol depletion resulted in blurring of IL-2R clusters (37) and impairment of IL-2 signaling (13). Actin was shown to induce coconfinement of FcεRI receptors, thereby influencing their long-range mobility and response to ligand binding (60). In this article we give a detailed view of the effects of knocking down a highly expressed member of a membrane protein cluster on the lateral organization and dynamics of the remaining elements of the cluster. The different methods used sample different molecular populations. FCS is sensitive to the mobile fraction of molecules, whereas STED microscopy and FRET report on the total molecular population.

The diffusion coefficient of MHC I, IL-2Rα, and IL-15Rα was in the range of 0.03–0.15 μm2/s for control cells according to our FCS analyses. The mobility of IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, and MHC I increased significantly (∼1.2–1.8-fold for the different proteins) upon KD of MHC I. This is compatible with the molecular interaction between MHC I and IL-2R/IL-15R suggested previously by our FRET and FCCS experiments (1, 13, 37), and implies a decrease of the size of protein aggregates accommodating these molecules. Molecular brightness data indicated that the extent of aggregation was highest for the MHC I molecules in control cells. FCS also revealed that the number of MHC I-containing aggregates decreased 10-fold and their specific brightness ∼1.7-fold. This clearly indicates that homoaggregation of MHC I depends strongly on its expression level. Altogether, brightness and mobility data suggest an overall decrease of the size of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα/MHC I aggregates. Bleaching observed during FCS measurements suggested that a large fraction of the studied proteins had little or no mobility; ∼50–70% of proteins were bleached over 20 s. The bleached fractions decreased upon MHC KD for the case of MHC I and IL-2Rα. Mobility measurements of IL-2/IL-15 receptors highlight the sensitivity of these receptors to their micromilieu: the change in the number of interacting partners can considerably affect their dynamic behavior. Because the lifetime of MHC I clusters was found to be controlled by the cytoskeleton (61), and a direct or indirect link between the cytoskeleton and IL-2/IL-15 receptors was also found (62), our data might suggest that MHC I could mediate interaction between the cytoskeleton and IL-2R/IL-15R. Even the D values measured after MHC KD are lower than those reported for related single-spanning membrane proteins (0.3–0.4 μm2/s for IL-13Rα and 0.1–0.2 μm2/s for IL-2Rγ on HEK293T cells (63)), corroborating the clusterization and/or cytoskeletal interaction of MHC I and IL-2R/IL-15R proteins on FT7.10 T cells.

When assessing diffusion coefficients in the membrane by FCS, a general concern is that long diffusion times of the studied molecules would necessitate long FCS measurements; e.g., for τD = 50 ms, 1000 × 50 ms = 50 s recording time would be necessary to estimate the diffusion coefficient adequately (64). However, photobleaching prompts the investigator to record shorter runs; thus, diffusion coefficients may be underestimated. In our case, this means that the real mobilities are even lower than those estimated by FCS.

FRET measurements gave insight into protein-protein interactions at the nanometer scale. Associations involving MHC I diminished upon its KD as indicated by the decrease of FRET efficiencies. Importantly, not only the homoassociation of MHC I diminished, but also the heterotypic interactions between IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα, and MHC I became less abundant, as expected. On the other hand, the interaction between IL-2R/IL-15R subunits did not change significantly, suggesting that the interactions holding these subunits together were not critically dependent on the presence of MHC I.

Previously we found that IL-2/15 receptors were associated with lipid rafts even in the absence of specific ligands (1), whereas other results suggested that the migration of IL-2 receptors to rafts was induced by ligand binding (62). Our present colocalization analyses suggest that the enrichment of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα in lipid rafts is constitutive, and it is not affected by removing MHC I molecules either. Other members of the common γc family of receptors were also found to be enriched in lipid rafts previously (10, 65, 66).

The application of superresolution STED microscopy allowed us to visualize and quantify larger protein clusters directly with a resolution of 40 nm. We assessed the distribution of supercluster sizes by three complementary image analysis methods: from the widths of intensity peaks, the correlation lengths of intensity distributions, and the number of pixels in contiguous high-intensity areas. These methods assess slightly different parameters of the superclusters, characterizing them at a length scale of a few tens to hundreds of nanometers. All three methods gave unequivocal results on KD-induced changes of cluster sizes. The mean supercluster size of MHC I was reduced by KD (from 400–600 to 200–300 nm). Conversely, the mean geometry of IL-2/15 receptor superclusters did not change drastically by removing their nearby MHC I partners. Colocalization analysis showed that the fraction of IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα residing in the vicinity of MHC I decreased after KD. This was paralleled by a decrease of the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between IL-2/15 receptors and MHC I probably due to the lower cell surface coverage of MHC I. On the other hand, the fraction of MHC I molecules residing in the vicinity of IL2-Rα/IL-15Rα did not change, suggesting a strong interaction between receptors and the remaining MHC I molecules.

Based on our data, we propose a model of co-clustering of IL-2/IL-15 receptors and MHC I and the effect of MHC I knockdown, as depicted in Fig. 7. We identified two levels of protein codistributions. STED microscopy revealed a supercluster size of 300–600 nm (15–30 pixels) for MHC I and IL-2/15 receptors (areas encircled by dashed or dotted lines in the scheme), similar in size to those found earlier by SNOM for IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα (∼450- and ∼360-nm average diameters) (67). These protein superclusters greatly overlap with GM1-rich lipid domains (rafts). The size of protein superclusters is similar to the lateral diameter of the FCS confocal volume (∼400-nm diameter), which contains an average number of N = 10–35 diffusing units or tight aggregates based on our FCS data (this N is an underestimation because, in an inhomogeneous system, dim aggregates are underweighted). Each of these units may consist of one or several proteins of a kind according to FCS brightness analysis, and a large fraction of these contain multiple protein species (IL-2Rα, IL-15Rα, MHC I, and MHC II) according to FRET. Taken together, our view is that lipid raft domains confine IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα, and MHC glycoproteins in superclusters (1, 13, 37, 57), in which smaller interacting tight aggregates are formed as identified by FCS and FRET. Some of these aggregates are mobile, while others have little or no mobility. Upon MHC I KD the mobility of these tight aggregates is increased, which is partially due to their lower MHC I content. A further reason for the increased mobility can be a lesser degree of molecular crowding (68) due to the lower overall MHC I content of the superclusters. After KD, MHC I retracts to smaller areas, as suggested by a higher fraction of MHC I-free IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα domains and the smaller correlation coefficients of codistributions of MHC I with IL-2Rα/IL-15Rα/GM1.

Figure 7.

A possible visualization of the effects of MHC I knockdown on the clustering of the IL-2/IL-15 receptor complex and MHC I molecules. Encircled areas mark protein superclusters as discerned by STED microscopy (red dashed line for MHC I and gray dotted line for IL-R superclusters), which contain several distinct tight aggregates of codiffusing proteins. Some of these aggregates are mobile, while others have little or no mobility. Upon MHC I KD, the MHC I content of the aggregates decreased, leading to a decrease of their size and an increase of their mobility. MHC I supercluster size decreased upon KD from 400–600 to 200–300 nm (marked by the decreased area of MHC I-containing regions encircled by red dashed lines), whereas the mean geometry of IL-2/IL-15 receptor superclusters did not change significantly. To see this figure in color, go online.

In conclusion, MHC I knockdown significantly influenced cell-surface supramolecular patterns. Changes of clustering properties induced by changes of MHC I expression level may modulate signaling properties of receptor complexes associated with MHC I. Our data demonstrate that modifying the expression of one element of a protein cluster can alter protein associations and the dynamic properties of the cluster.

Author Contributions

G.M. and J.V. carried out most experiments with contributions from G.V., A.B., D.R., and K.T.; G.M. and J.V. analyzed most experiments with contributions from G.V. and D.R.; G.M. carried out simulations; P.N. designed siRNA; C.K.G. provided reagents and cells; G.M. and G.V. wrote the article with inputs from K.T., J.S., S.D., T.A.W., P.N., J.W.; G.V. and G.M. conceived the experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edina Nagy and Rita Szabó for technical assistance and Drs. János Matkó and Malte Renz for helpful discussions and comments on the article.

This work was supported by Hungarian Scientific Research Fund grant No. K103965 to G.V., grant No. K103906 to P.N., and grant No. NK101337 to J.S.; the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health to T.A.W.; TÁMOP grant No. 4.2.2.-08/1-2008-0019 to G.V.; “MOLMEDREX” FP7-REGPOT-2008-1 grant No. 229920 to G.V.; German Academic Exchange Service and Tempus Public Foundation Hungary grant No. 73163 to G.V. and K.T.; Internal Research Program of the University of Debrecen grant No. RH/885/2013 to A.B.; Jedlik Ányos Fellowship grant No. A2-JÁDJ-13-0170 to G.M.; TÁMOP-4.2.2.A-11/1/KONV-2012-0023 VÉD-ELEM and TÁMOP-4.2.2.D-15/1/KONV-2015-0016 grants implemented through the New Hungary Development Plan cofinanced by the European Social Fund and the European Regional Development Fund to G.V. and J.S.; and the European Union and the State of Hungary, cofinanced by the European Social Fund in the framework of TÁMOP-4.2.4.A/ 2-11/1-2012-0001 National Excellence Program to G.V.

Editor: Anne Kenworthy.

Footnotes

Gábor Mocsár and Julianna Volkó contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Materials and Methods, ten figures, and two tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30391-5.

Supporting Citations

References (69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Vámosi G., Bodnár A., Damjanovich S. IL-2 and IL-15 receptor α-subunits are coexpressed in a supramolecular receptor cluster in lipid rafts of T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11082–11087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403916101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodnár A., Nizsalóczki E., Vámosi G. A biophysical approach to IL-2 and IL-15 receptor function: localization, conformation and interactions. Immunol. Lett. 2008;116:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodsky F.M., Guagliardi L.E. The cell biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991;9:707–744. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bene L., Balázs M., Damjanovich S. Lateral organization of the ICAM-1 molecule at the surface of human lymphoblasts: a possible model for its co-distribution with the IL-2 receptor, class I and class II HLA molecules. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:2115–2123. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damjanovich S., Vereb G., Jovin T.M. Structural hierarchy in the clustering of HLA class I molecules in the plasma membrane of human lymphoblastoid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:1122–1126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenei A., Varga S., Damjanovich S. HLA class I and II antigens are partially co-clustered in the plasma membrane of human lymphoblastoid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7269–7274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matkó J., Bushkin Y., Edidin M. Clustering of class I HLA molecules on the surfaces of activated and transformed human cells. J. Immunol. 1994;152:3353–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bene L., Bodnár A., Damjanovich J. Membrane topography of HLA I, HLA II, and ICAM-1 is affected by IFN-γ in lipid rafts of uveal melanomas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;322:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy P., Vámosi G., Damjanovich L. ICAM-1 inhibits the homocluster formation of MHC-I in colon carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;347:758–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nizsaloczki E., Csomos I., Bodnar A. Distinct spatial relationship of the interleukin-9 receptor with interleukin-2 receptor and major histocompatibility complex glycoproteins in human T lymphoma cells. ChemPhysChem. 2014;15:3969–3978. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szöllösi J., Damjanovich S., Brodsky F.M. Physical association between MHC class I and class II molecules detected on the cell surface by flow cytometric energy transfer. J. Immunol. 1989;143:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiber A.B., Schlessinger J., Edidin M. Interaction between major histocompatibility complex antigens and epidermal growth factor receptors on human cells. J. Cell Biol. 1984;98:725–731. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matkó J., Bodnár A., Damjanovich S. GPI-microdomains (membrane rafts) and signaling of the multi-chain interleukin-2 receptor in human lymphoma/leukemia T cell lines. Eur. J. Biochem. FEBS. 2002;269:1199–1208. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2002.02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bene L., Kanyári Z., Damjanovich L. Colorectal carcinoma rearranges cell surface protein topology and density in CD4+ T cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;361:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edidin M., Reiland J. Dynamic measurements of the associations between class I MHC antigens and insulin receptors. Mol. Immunol. 1990;27:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiland J., Edidin M. Chemical cross-linking detects association of insulin receptors with four different class I human leukocyte antigen molecules on cell surfaces. Diabetes. 1993;42:619–625. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liegler T., Szollosi J., Goodenow R.S. Proximity measurements between H-2 antigens and the insulin receptor by fluorescence energy transfer: evidence that a close association does not influence insulin binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:6755–6759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szöllósi J., Horejsí V., Damjanovich S. Supramolecular complexes of MHC class I, MHC class II, CD20, and tetraspan molecules (CD53, CD81, and CD82) at the surface of a B cell line JY. J. Immunol. 1996;157:2939–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mátyus L., Bene L., Damjanovich S. Distinct association of transferrin receptor with HLA class I molecules on HUT-102B and JY cells. Immunol. Lett. 1995;44:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00215-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramalingam T.S., Chakrabarti A., Edidin M. Interaction of class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA-I) molecules with insulin receptors and its effect on the insulin-signaling cascade. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:2463–2474. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assa-Kunik E., Fishman D., Segal S. Alterations in the expression of MHC class I glycoproteins by B16BL6 melanoma cells modulate insulin receptor-regulated signal transduction and augment resistance to apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2003;171:2945–2952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen A.E., Skov S., Claesson M.H. Signal transduction by the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule. APMIS. 1999;107:887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skov S., Klausen P., Claesson M.H. Ligation of major histocompatability complex (MHC) class I molecules on human T cells induces cell death through PI-3 kinase-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity: a novel apoptotic pathway distinct from Fas-induced apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:1523–1531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arosa F.A., Santos S.G., Powis S.J. Open conformers: the hidden face of MHC-I molecules. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowness P., Caplan S., Edidin M. MHC molecules lead many lives. Workshop on MHC Class I Molecules at the interface between Biology & Medicine. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:30–34. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehniger T.A., Cooper M.A., Caligiuri M.A. Interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: immunotherapy for cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:169–183. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldmann T.A. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat. Rev. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damjanovich S., Bene L., Waldmann T.A. Preassembly of interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor subunits on resting Kit 225 K6 T cells and their modulation by IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13134–13139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson B.H., Lord J.D., Greenberg P.D. Cytoplasmic domains of the interleukin-2 receptor β and γ chains mediate the signal for T-cell proliferation. Nature. 1994;369:333–336. doi: 10.1038/369333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J.X., Migone T.S., Leonard W.J. The role of shared receptor motifs and common Stat proteins in the generation of cytokine pleiotropy and redundancy by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-13, and IL-15. Immunity. 1995;2:331–339. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson B.H., Willerford D.M. Biology of the interleukin-2 receptor. Adv. Immunol. 1998;70:1–81. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldmann T.A., Dubois S., Tagaya Y. Contrasting roles of IL-2 and IL-15 in the life and death of lymphocytes: implications for immunotherapy. Immunity. 2001;14:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai Z., Arakelov A., Lakkis F.G. The role of the common cytokine receptor γ-chain in regulating IL-2-dependent, activation-induced CD8+ T cell death. J. Immunol. 1999;163:3131–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szöllösi J., Damjanovich S., Waldmann T.A. Flow cytometric resonance energy transfer measurements support the association of a 95-kDa peptide termed T27 with the 55-kDa Tac peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7246–7250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harel-Bellan A., Krief P., Mishal Z. Flow cytometry resonance energy transfer suggests an association between low-affinity interleukin 2 binding sites and HLA class I molecules. Biochem. J. 1990;268:35–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2680035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edidin M., Aszalos A., Waldmann T.A. Lateral diffusion measurements give evidence for association of the Tac peptide of the IL-2 receptor with the T27 peptide in the plasma membrane of HUT-102-B2 T cells. J. Immunol. 1988;141:1206–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vereb G., Matkó J., Damjanovich S. Cholesterol-dependent clustering of IL-2Rα and its colocalization with HLA and CD48 on T lymphoma cells suggest their functional association with lipid rafts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6013–6018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sege K., Rask L., Peterson P.A. Role of β2-microglobulin in the intracellular processing of HLA antigens. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4523–4530. doi: 10.1021/bi00519a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubois S., Mariner J., Tagaya Y. IL-15Rα recycles and presents IL-15 in trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. 2002;17:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams D.B., Barber B.H., Allen H. Role of β2-microglobulin in the intracellular transport and surface expression of murine class I histocompatibility molecules. J. Immunol. 1989;142:2796–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elson E.L. Brief introduction to fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2013;518:11–41. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-388422-0.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weidemann T. Application of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) to measure the dynamics of fluorescent proteins in living cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1076:539–555. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-649-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck Z., Balogh A., Matko J. New cholesterol-specific antibodies remodel HIV-1 target cells’ surface and inhibit their in vitro virus production. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:286–296. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mocsár G., Kreith B., Vámosi G. Note: multiplexed multiple-tau auto- and cross-correlators on a single field programmable gate array. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012;83:046101. doi: 10.1063/1.3700810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrov E.P., Ohrt T., Schwille P. Diffusion and segmental dynamics of double-stranded DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:258101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.258101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger, J., and J. Langowski. 2015. QuickFit 3.0 (status: beta, compiled: 2015–03–18, SVN: 3891): A data evaluation application for biophysics. http://www.dkfz.de/Macromol/quickfit/.

- 47.Sebestyén Z., Nagy P., Szöllosi J. Long wavelength fluorophores and cell-by-cell correction for autofluorescence significantly improves the accuracy of flow cytometric energy transfer measurements on a dual-laser benchtop flow cytometer. Cytometry. 2002;48:124–135. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szentesi G., Horváth G., Mátyus L. Computer program for determining fluorescence resonance energy transfer efficiency from flow cytometric data on a cell-by-cell basis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wildanger D., Rittweger E., Hell S.W. STED microscopy with a supercontinuum laser source. Opt. Express. 2008;16:9614–9621. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.009614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bückers J., Wildanger D., Hell S.W. Simultaneous multi-lifetime multi-color STED imaging for colocalization analyses. Opt. Express. 2011;19:3130–3143. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.003130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rönnlund D., Gad A.K., Widengren J. Spatial organization of proteins in metastasizing cells. Cytometry A. 2013;83:855–865. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blom H., Rönnlund D., Brismar H. Nearest neighbor analysis of dopamine D1 receptors and Na+-K+-ATPases in dendritic spines dissected by STED microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2012;75:220–228. doi: 10.1002/jemt.21046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hwang J., Gheber L.A., Edidin M. Domains in cell plasma membranes investigated by near-field scanning optical microscopy. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2184–2190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77927-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sengupta P., Jovanovic-Talisman T., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Quantifying spatial organization in point-localization superresolution images using pair correlation analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:345–354. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrou M., Petrou C. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2010. Image Processing: The Fundamentals. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garcia-Parajo M.F., Cambi A., Jacobson K. Nanoclustering as a dominant feature of plasma membrane organization. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:4995–5005. doi: 10.1242/jcs.146340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vereb G., Szöllosi J., Damjanovich S. Dynamic, yet structured: the cell membrane three decades after the Singer-Nicolson model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8053–8058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332550100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kusumi A., Nakada C., Fujiwara T. Paradigm shift of the plasma membrane concept from the two-dimensional continuum fluid to the partitioned fluid: high-speed single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:351–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lajoie P., Goetz J.G., Nabi I.R. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:381–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews N.L., Lidke K.A., Lidke D.S. Actin restricts FcεRI diffusion and facilitates antigen-induced receptor immobilization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:955–963. doi: 10.1038/ncb1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lavi Y., Gov N., Gheber L.A. Lifetime of major histocompatibility complex class-I membrane clusters is controlled by the actin cytoskeleton. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pillet A.H., Lavergne V., Rose T. IL-2 induces conformational changes in its preassembled receptor core, which then migrates in lipid raft and binds to the cytoskeleton meshwork. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;403:671–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gandhi H., Worch R., Weidemann T. Dynamics and interaction of interleukin-4 receptor subunits in living cells. Biophys. J. 2014;107:2515–2527. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elson E.L. Introduction. In: Rigler R., Elson E.L., editors. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. Theory and Applications. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2001. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rose T., Pillet A.H., Thèze J. Interleukin-7 compartmentalizes its receptor signaling complex to initiate CD4 T lymphocyte response. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14898–14908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 66.Tamarit B., Bugault F., Rose T. Membrane microdomains and cytoskeleton organization shape and regulate the IL-7 receptor signalosome in human CD4 T-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8691–8701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.449918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Bakker B.I., Bodnár A., Garcia-Parajo M.F. Nanometer-scale organization of the α-subunits of the receptors for IL2 and IL15 in human T lymphoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:627–633. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou H.X., Rivas G., Minton A.P. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barnstable C.J., Bodmer W.F., Ziegler A. Production of monoclonal antibodies to group A erythrocytes, HLA and other human cell surface antigens—new tools for genetic analysis. Cell. 1978;14:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brazda P., Szekeres T., Nagy L. Live-cell fluorescence correlation spectroscopy dissects the role of coregulator exchange and chromatin binding in retinoic acid receptor mobility. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:3631–3642. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brizzard B.L., Chubet R.G., Vizard D.L. Immunoaffinity purification of FLAG epitope-tagged bacterial alkaline phosphatase using a novel monoclonal antibody and peptide elution. Biotechniques. 1994;16:730–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lampson L.A., Fisher C.A., Whelan J.P. Striking paucity of HLA-A, B, C and β2-microglobulin on human neuroblastoma cell lines. J. Immunol. 1983;130:2471–2478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mets U., Rigler R. Submillisecond detection of single rhodamine molecules in water. J. Fluoresc. 1994;4:259–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01878461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubin L.A., Kurman C.C., Nelson D.L. A monoclonal antibody 7G7/B6, binds to an epitope on the human interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor that is distinct from that recognized by IL-2 or anti-Tac. Hybridoma. 1985;4:91–102. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1985.4.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsudo M., Kitamura F., Miyasaka M. Characterization of the interleukin 2 receptor β-chain using three distinct monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:1982–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uchiyama T., Broder S., Waldmann T.A. A monoclonal antibody (anti-Tac) reactive with activated and functionally mature human T cells. I. Production of anti-Tac monoclonal antibody and distribution of Tac+ cells. J. Immunol. 1981;126:1393–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uchiyama T., Nelson D.L., Waldmann T.A. A monoclonal antibody (anti-Tac) reactive with activated and functionally mature human T cells. II. Expression of Tac antigen on activated cytotoxic killer T cells, suppressor cells, and on one of two types of helper T cells. J. Immunol. 1981;126:1398–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.