Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) during sepsis is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, but practice patterns and outcomes associated with rate- and rhythm-targeted treatments for AF during sepsis are unclear.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study using enhanced billing data from approximately 20% of United States hospitals. We identified factors associated with IV AF treatments (β-blockers [BBs], calcium channel blockers [CCBs], digoxin, or amiodarone) during sepsis. We used propensity score matching and instrumental variable approaches to compare mortality between AF treatments.

Results

Among 39,693 patients with AF during sepsis, mean age was 77 ± 11 years, 49% were women, and 76% were white. CCBs were the most commonly selected initial AF treatment during sepsis (14,202 patients [36%]), followed by BBs (11,290 [28%]), digoxin (7,937 [20%]), and amiodarone (6,264 [16%]). Initial AF treatment selection differed according to geographic location, hospital teaching status, and physician specialty. In propensity-matched analyses, BBs were associated with lower hospital mortality when compared with CCBs (n = 18,720; relative risk [RR], 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.97), digoxin (n = 13,994; RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.75-0.85), and amiodarone (n = 5,378; RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.61-0.69). Instrumental variable analysis showed similar results (adjusted RR fifth quintile vs first quintile of hospital BB use rate, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.58-0.79). Results were similar among subgroups with new-onset or preexisting AF, heart failure, vasopressor-dependent shock, or hypertension.

Conclusions

Although CCBs were the most frequently used IV medications for AF during sepsis, BBs were associated with superior clinical outcomes in all subgroups analyzed. Our findings provide rationale for clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of AF rate- and rhythm-targeted treatments during sepsis.

Key Words: atrial fibrillation, health care utilization, sepsis

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BB, β-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; IQR, interquartile range; RR, relative risk

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT SEE PAGE 9

Sepsis affects more than 1 million hospitalized patients yearly in the United States1 and is associated with one in three hospital deaths.2 Approximately 25% of patients hospitalized with sepsis also have atrial fibrillation (AF),3 the most common sustained arrhythmia among hospitalized patients.4, 5 The occurrence of AF during sepsis portends poor short- and long-term outcomes, with associated increased risks of stroke, heart failure, and death.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Multiple factors complicate treatment of AF that occurs during sepsis, and little evidence guides its management. For example, direct current cardioversion is a guideline-recommended treatment of AF resulting in acute clinical decompensation.11 However, cardioversion is often unsuccessful for AF rhythm control during sepsis,12 few patients with sepsis demonstrate clear hemodynamic collapse due to AF, and cardioversion of unclear-duration AF may be associated with thromboembolic events.11 β-blocker (BB) and calcium channel blocker (CCB) medications may be used to slow atrioventricular nodal conduction and lower supraphysiologic heart rates but may also exacerbate hypotension among patients with distributive states such as septic shock.13 Cardiac glycosides (digoxin) may be selected to reduce heart rates without inducing hypotension but may be less effective in high catecholamine states14 and have low therapeutic index in the setting of renal dysfunction, which is commonly encountered during sepsis.15 Amiodarone may be selected as a rate- or rhythm-controlling agent for AF during critical illnesses such as sepsis,11 but it also presents risks for proarrhythmia, drug interactions, and multiple organ toxicities.13, 16

To inform current knowledge gaps regarding AF treatment during critical illness,17 we sought to identify current clinical practice patterns and compare effectiveness between treatment strategies for AF among a large cohort of patients hospitalized with sepsis. We aimed to determine hospital-level variation in choice of initial AF therapy to explore our hypothesis that choice of treatment of AF during sepsis is subject to wide practice pattern variation. In addition, we sought to compare outcomes of patients based on initial AF treatment selection.

Materials and Methods

Sepsis Cases

We identified a cohort of adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) from an enhanced administrative database (Premier, Inc) with an initial sepsis hospitalization during the years 2010 to 2013. Patients included in Premier represent approximately 20% of hospitalized patients in nonfederal hospitals in the United States (see e-Appendix 1 for further details). Patients admitted with sepsis were identified through use of high positive predictive value (> 90%)18 explicit sepsis International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes present on admission combined with receipt of an antibiotic on the first hospital day. Patients with sepsis were classified as having AF via ICD-9-CM 427.31 (positive predictive value, 70%-96%; median, 89%).19 Patients with AF were subclassified as having “preexisting AF” (if AF was present on admission) or “new-onset AF” (if AF was not present on admission).6

AF Treatments

We searched pharmacy billing files for IV doses of CCBs (diltiazem, verapamil), BBs (metoprolol, esmolol, atenolol, labetalol, propranolol), digoxin (cardiac glycosides, digoxin, digitalis), and amiodarone. We restricted our analysis to IV AF therapy to avoid unmeasured confounding due to patients’ ability to take oral medications and to identify clinically significant AF requiring acute rate or rhythm control treatment. Drug use was extracted from pharmacy billing files and included information for hospital day of administration, quantity, and dosing. Because we were unable to determine the initial AF treatment when multiple different AF treatments were given during the same hospital day, in our primary analysis we excluded patients receiving multiple AF treatments on the same hospital day (Fig 1). To increase likelihood that AF treatments were given during sepsis, we included only AF treatments given during the first 14 days of the sepsis hospitalization, on the same day as an antibiotic.

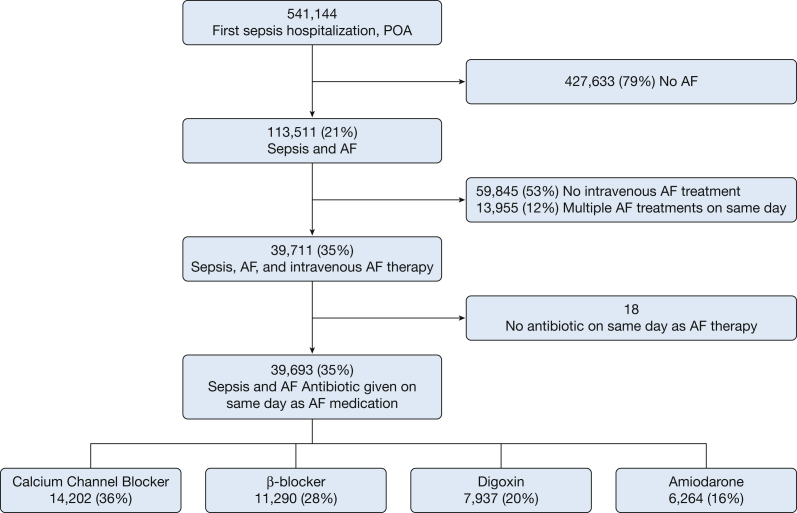

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion. AF = atrial fibrillation; POA = sepsis present on admission.

Covariates, Outcomes, and Subgroups

We collected information for year of hospitalization, patient demographics, comorbid conditions, present on admission acute organ failures, organ-supportive therapies (first hospital day), source of sepsis (e-Table 1), and provider and hospital characteristics. Based on the potential for treatment effect modification, we created a priori subgroups based on AF type (new onset vs preexisting), use of vasopressor medications during administration of AF medication, and the presence of heart failure. We investigated patient and hospital factors associated with choice of each AF treatment and hospital mortality associated with choice of AF treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Details on statistical methods are described in e-Appendix 1. We used a propensity score matching approach to adjust for measured confounding in the selection of AF treatments. Nonparsimonious propensity scores including all measured covariates (e-Table 1) and time to first AF medication were calculated using generalized estimating equations with robust standard error calculations accounting for within-hospital correlation.20 Based on preliminary analyses, we compared BBs to each of the three other classes of AF medications.

To estimate potential unmeasured confounding by indication in our propensity score analyses, we performed individual patient-level multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analysis using hospital-level percentage of BB use among patients with AF during sepsis as an instrument for AF treatment selection.21

We estimated the proportion of between-hospital variation in selection of BB as initial AF treatment that was unexplained by hospital, provider, or patient characteristics by calculating intraclass correlation coefficients from multivariable hierarchical logistic regression models.22, 23, 24

We used SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc)for all analyses and selected a two-sided α level of 0.05. Boston University Medical Center institutional review board approved all study procedures (protocol H-31821).

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed a number of analyses to explore the robustness of findings. We performed a sensitivity analysis broadening our inclusion criteria to allow patients who may have received multiple IV AF treatments on the initial AF treatment day into the analysis. Because BBs or CCBs may be used to treat hypertension as well as AF, we performed an additional subgroup analysis stratified by the presence of a hypertension diagnosis. As an exploratory surrogate estimate of each medication reaching its intended therapeutic efficacy, we investigated the relative probability of requiring any subsequent change in IV AF treatment after the initial therapy, among survivors.

Results

Sepsis Cohort

Among 541,144 patients hospitalized with sepsis, we identified 113,511 (21%) with both sepsis and AF. Most patients with AF and sepsis (59,845 [60%]) did not receive IV therapy. We analyzed 39,693 patients with AF and sepsis (35%) who received IV rate- or rhythm-control AF treatment (Fig 1). Patients with sepsis and AF were 77 ± 11 years of age, 49% were women, and 76% were white. Among patients who received IV AF treatment during sepsis, CCBs were the most frequently used initial medications (14,202 [36%]), followed by BBs (11,290 [28%]), digoxin (7,937 [20%]), and amiodarone (6,264 [16%]). Patient and hospital characteristics associated with receipt of each IV AF therapy, prior to propensity matching, are shown in Table 1 and e-Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Sepsis According to Initial IV Atrial Fibrillation Medication

| Variable | β-Blocker | Calcium Channel Blocker | Digoxin | Amiodarone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | 11,290 (11.3) | 14,202 (14.3) | 7,937 (8.0) | 6,264 (6.3) |

| Age, y | 75.7 ± 11.3 | 75.6 ± 11.4 | 77.1 ± 10.7 | 73.1 ± 11.7 |

| Women | 5,598 (49.6) | 7,476 (52.6) | 4,088 (51.5) | 2,814 (44.9) |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||

| White | 8,417 (74.6) | 10,959 (77.2) | 5,974 (75.3) | 4,523 (72.2) |

| Black | 974 (8.6) | 1,028 (7.2) | 567 (7.1) | 640 (10.2) |

| Hispanic | 76 (0.7) | 96 (0.7) | 84 (1.1) | 65 (1.0) |

| Other | 1,823 (16.1) | 2,119 (14.9) | 1,312 (16.5) | 1,036 (16.5) |

| Geographic location | ||||

| Northeast | 2,921 (25.9) | 2,137 (15.0) | 1,398 (17.6) | 755 (12.1) |

| Midwest | 2,199 (19.5) | 2,947 (20.8) | 1,566 (19.7) | 1,224 (19.5) |

| South | 4,189 (37.1) | 6,249 (44.0) | 3,136 (39.5) | 2,812 (44.9) |

| West | 1,981 (17.5) | 2,869 (20.2) | 1,837 (23.1) | 1,473 (23.5) |

| Teaching hospital | 5,098 (45.2) | 4,950 (34.9) | 2,724 (34.3) | 2,630 (42.0) |

| Attending specialty | ||||

| Internal medicine | 9,375 (83.1) | 12,710 (89.5) | 6,958 (87.7) | 4,950 (79.1) |

| Surgical | 892 (7.9) | 351 (2.5) | 211 (2.7) | 357 (5.7) |

| Pulmonary/critical care | 809 (7.2) | 928 (6.5) | 592 (7.5) | 732 (11.7) |

| Cardiology | 207 (1.8) | 206 (1.5) | 173 (2.2) | 221 (3.5) |

| Comorbidities | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 1.8 |

| Acute organ failures | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.4 |

| Intensive care stay | 6,406 (56.7) | 7,487 (52.7) | 4,862 (61.3) | 4,730 (75.5) |

| Intensive care procedures | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation on first hospital day | 1,842 (16.3) | 1,698 (12.0) | 1,345 (16.9) | 1,932 (30.8) |

| Hemodialysis on first hospital day | 1,157 (10.2) | 1,126 (7.9) | 804 (10.1) | 1,187 (18.9) |

| Vasopressors on first hospital day | 3,291 (29.1) | 3,770 (26.5) | 3,504 (44.1) | 4,012 (64.0) |

| Infection site | ||||

| Pneumonia | 3,583 (31.7) | 5,882 (41.4) | 3,118 (39.3) | 2,369 (37.8) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 2,107 (18.7) | 1,692 (11.9) | 1,030 (13.0) | 896 (14.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4,173 (37.0) | 5,439 (38.3) | 3,008 (37.9) | 1,980 (31.6) |

| Skin or soft tissue infection | 982 (8.7) | 1,217 (8.6) | 696 (8.8) | 507 (8.1) |

| Primary bacteremia or fungemia | 140 (1.2) | 150 (1.1) | 82 (1.0) | 76 (1.2) |

| Do not resuscitate | 1,596 (14.1) | 2,143 (15.1) | 1,307 (16.5) | 788 (12.6) |

| Use of therapeutic anticoagulation | 2,207 (19.6) | 3,025 (21.3) | 1,387 (17.5) | 1,440 (23.0) |

| Year of sepsis hospitalization | ||||

| 2010 | 1,555 (13.8) | 2,054 (14.5) | 1,297 (16.3) | 879 (14.0) |

| 2011 | 3,651 (32.3) | 4,619 (32.5) | 2,796 (35.2) | 2,084 (33.3) |

| 2012 | 3,974 (35.2) | 4,971 (35.0) | 2,648 (33.4) | 2,173 (34.7) |

| 2013 | 2,110 (18.7) | 2,558 (18.0) | 1,196 (15.1) | 1,128 (18.0) |

| Time to first AF medication, median, (25th-75th percentile), d | 2 (1-4) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

Data presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Characteristics are shown before propensity matching. AF = atrial fibrillation.

BBs vs CCBs

Multivariable-adjusted factors associated with receipt of CCBs as compared with BBs are shown in e-Table 3. Patients receiving CCBs were more likely younger, women, and white, and had fewer comorbid conditions; CCBs were less likely to be used in hospitals located in the Northeast, in teaching hospitals, and by surgeons.

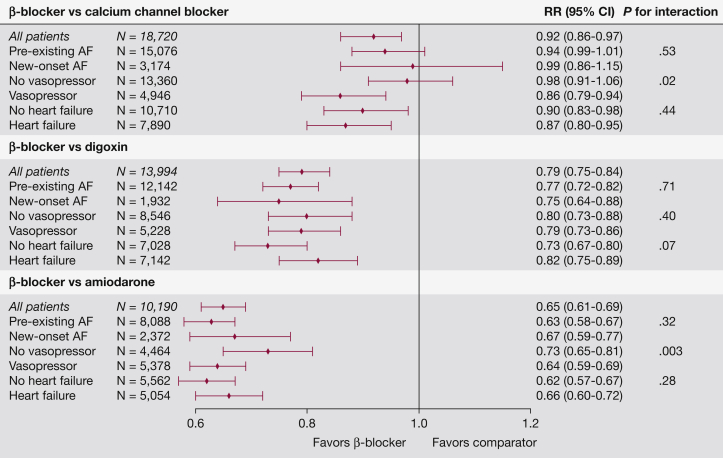

Distributions of propensity scores were similar for BBs and CCBs (e-Fig 1), and covariates were well-matched by propensity scores (e-Table 4). Among propensity-matched patients with sepsis and AF, hospital mortality was significantly lower for patients initially treated with BBs (18.3%) as compared with CCBs (20.0%) (n = 18,720; relative risk [RR], 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.97), with no effect modification by type of AF (new onset vs preexisting, P for interaction = .65) or by a history of heart failure (P for interaction = .44). Patients with vasopressor infusion at the time of receiving AF treatment showed lower mortality associated with BBs than CCBs (shock: RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79-0.94; no shock: RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91-1.06; P for interaction = .01).

Digoxin vs BBs

Multivariable-adjusted factors associated with receipt of digoxin as compared with BBs are shown in e-Table 3. Patients receiving digoxin were more likely older and more likely to have prevalent heart failure, valvular disease, cancer, cirrhosis, COPD, or shock. Digoxin was less likely provided in hospitals located outside the Northeast, in teaching hospitals, and by surgeons. Digoxin was used less frequently over time.

The distributions of propensity scores were similar for digoxin and BBs (e-Fig 2), and after propensity score matching all measured covariates were well balanced (e-Table 5). Among 13,994 propensity-matched patients with sepsis and AF treated with digoxin as compared with BBs, digoxin use was associated with greater hospital mortality (25.7%) than BBs (20.5%). Digoxin use was associated with worse outcomes in all subgroups analyzed, including patients with shock (P for interaction = .40), by AF type (preexisting vs new onset; P for interaction = .71), and among patients with comorbid heart failure (P for interaction = .067).

Amiodarone vs BBs

Amiodarone was most likely to be used among patients who were critically ill with septic shock (Table 1, e-Table 2). Factors associated with use of amiodarone as compared with BBs among patients with shock are shown in e-Table 3. Patients receiving amiodarone were more likely to have heart failure, new-onset AF, cancer, and acute organ failures. Amiodarone was more likely ordered by pulmonary and critical care physicians and in hospitals located outside the Northeast. The distributions of propensity scores were similar for BBs and amiodarone (e-Fig 3), and after propensity score matching all measured covariates were well balanced (e-Table 6). Among 5,388 matched patients with a shock diagnosis who received a vasopressor on the same day as an AF medication, patients who received amiodarone experienced higher hospital mortality (42%) than patients receiving BBs (27%), P < .001. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated similar results among all matched patients, patients not in shock, new-onset or preexisting AF, and by presence of heart failure. A summary of all hospital mortality analyses is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of analyses for AF treatments during sepsis and relative risk for mortality. The number of subjects and weighted average of RR in the stratified analyses may differ from the analysis of all patients because a new propensity score was calculated to match each subgroup. RR = relative risk. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Hospital-Level BB Use

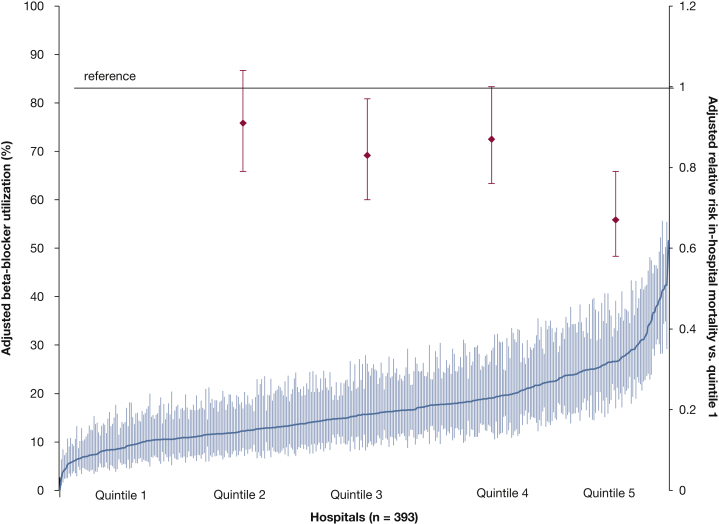

Hospitals showed practice pattern variation in the proportion of patients with sepsis and AF who received initial treatment with CCBs (median hospital rate, 34%; interquartile range [IQR], 34%-45%), BBs (median hospital rate, 25.7%; IQR, 18.7%-35.9%), digoxin (median hospital rate, 18.7%; IQR, 21.1%-27.5%), or amiodarone (median hospital rate, 13.5%; IQR, 6.6%-20.4%) as the initial AF medication. The proportion of between-hospital variation in choice of BBs as initial AF therapy unexplained by hospital, provider, or patient clinical characteristics was 9.5% (95% CI, 8.2%-11.3%). Rates of BBs as initial AF treatment of patients with AF and sepsis within each hospital are shown in Figure 3, along with multivariable-adjusted association between hospital-level BB use and patient-level mortality. Hospital BB use was strongly associated with patient-level BB use (P < .001), and patient characteristics were uniformly distributed across hospital quintiles of BB use rate (e-Table 7). Greater hospital-level rates of BB use as initial AF medication during sepsis were associated with reduced individual risk for mortality (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.58-0.79; P < .001, fifth quintile vs first quintile of BB use).

Figure 3.

Caterpillar plot of multivariable-adjusted utilization rates of β-blocker as initial medication for atrial fibrillation for each hospital (left y-axis). Superimposed is the multivariable-adjusted relative risk of hospital morality (right y-axis) associated with each quintile (2-5) of hospital β-blocker utilization as compared with quintile 1. The x-axis shows hospitals treating patients with sepsis and atrial fibrillation, sorted in order of increasing rate of β-blocker use.

Sensitivity Analyses

Broadening criteria to include patients who received multiple AF treatments on the initial day of AF rate or rhythm therapy did not substantively change our results, nor did stratifying patients by a diagnosis of hypertension (e-Table 8). Compared with patients who received CCBs, digoxin, or amiodarone, patients who received BBs as initial AF medication were equally likely to require a switch to another, subsequent AF medication (RR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.98-1.02).

Discussion

We examined practice patterns and outcomes associated with initial choice of IV therapy for rate or rhythm control in AF that occurred during sepsis. Although CCBs were the most commonly administered IV AF medication class during sepsis, selection of initial AF medications varied widely. After matching on observed patient characteristics, BB use during AF was associated with improved hospital mortality as compared with CCBs, digoxin, or amiodarone. Our findings did not show significant effect modification among multiple clinically relevant subgroups including AF timing, presence of shock, heart failure, and hypertension history.

Few studies have investigated practice patterns associated with choice of AF treatments among critically ill patients or those with sepsis. We identified a preference for CCBs as initial therapy for patients with AF during sepsis, a finding that differs from therapies observed in patients with chronic AF enrolled in trials.25 Selection of AF treatment during sepsis differed according to hospital factors such as geographic location, hospital teaching status, and physician specialty, as well as patient clinical characteristics. Approximately 10% of the variation in choice of initial AF medication between hospitals was unexplained. Practice pattern variation in AF treatment selection suggests lack of a current “standard of care” for treating AF during sepsis.

We are unaware of prior clinical outcome comparisons between rate control therapies among patients with AF and sepsis. However, indirect evidence supports our finding of an association between use of BBs and improved outcomes among patients with sepsis. Older, small, single-center trials comparing BBs with CCBs among patients with new-onset AF outside the critical care setting have suggested increased rates of conversion to sinus rhythm among patients receiving BBs, without immediate differences in achieving heart rate control.26, 27, 28, 29 A single-center trial30 demonstrating improved mortality among patients with septic shock and sinus tachycardia randomized to receive the BB esmolol further supports our finding that BBs may have clinical benefit during sepsis. Although potential mechanisms for beneficial effects of BBs during sepsis are unclear, experimental data support enhanced microvascular,31 antiinflammatory,32 and gut mucosal integrity33 with use of BBs during sepsis.

Digoxin may be theoretically attractive to some clinicians as an AF treatment during sepsis by potentially improving heart rate without inducing hypotension. However, concerns regarding digoxin toxicity—especially among the elderly and patients with renal insufficiency—may limit enthusiasm for use of digoxin for AF during sepsis. The observed decline in use of digoxin over time among patients with sepsis is in line with studies in other clinical settings showing waning use of digoxin to treat AF.34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Our results showing increased hospital mortality associated with receipt of digoxin support concerns regarding potential toxicities associated with digoxin.34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Amiodarone has theoretical advantages of achieving rate and rhythm control with fewer hypotensive side effects than BBs or CCBs during sepsis. However, our findings of increased mortality associated with amiodarone use do not support a strong clinical benefit for amiodarone in the sepsis setting. Our findings are in accord with small, single-center trials that have previously compared amiodarone to rate-control therapies among critically ill patients with AF. In a trial comparing IV amiodarone to digoxin in 50 hospitalized patients with new-onset AF, amiodarone was associated with greater conversion to sinus rhythm at 24 h (92%) than digoxin (71%) but with more adverse reactions among patients receiving amiodarone, including bradycardia and death.16 IV amiodarone was compared with magnesium among 42 critically ill patients with atrial tachyarrhythmia in a single center, with inferior rates of cardioversion and more adverse events.39 Further studies identifying rates of toxicity associated with use of amiodarone among noncardiac critically ill patients are warranted.

Our findings should be considered in the context of our study’s limitations. First, we used enhanced administrative data that lacked detailed sequence of events from chart review. In addition, ICD-9 codes do not often individually reflect disease severity, though taken together ICD-9 codes may produce risk adjustment in line with commonly used severity of illness scores based on physiologic measurements.40 Second, unmeasured confounding by disease severity or unmeasured clinical factors may influence our effect estimates, which may be more pronounced for treatments such as digoxin or amiodarone that may be selected with the goal of limiting hypotensive side effects. However, our cohorts were well-matched, and results were consistent using an instrumental variable method intended to attenuate residual confounding and were observed in multiple predefined subgroups. Third, although we examined assumptions that our instrumental variable was unlikely to be associated with patient severity of illness, we cannot rule out associations between our instrumental variable and other hospital practice patterns associated with mortality that may confound and decrease the validity of our instrumental variable analysis. Fourth, we could not measure intermediate outcomes such as heart rate control or conversion to sinus rhythm. Patients receiving BBs were equally likely as those receiving other medications to require subsequent changes in AF medication, a finding that may suggest similar intermediate outcomes between medication classes. We did not adjust for receipt of therapeutic anticoagulation; however, anticoagulation use was not systematically different between BBs and other rate- or rhythm-control treatments. Fifth, we were unable to accurately measure use of emergent cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Sixth, we were unable to determine relation of the patients’ home AF medication to the medication received during sepsis; however, results were similar among patients with new-onset AF and patients without hypertension who would not have received AF rate control medications prior to the sepsis hospitalization. Given the limitations of our data, our outcome findings should be considered hypothesis generating and supportive of the need for future clinical trials to investigate optimal treatment of AF during sepsis.

In conclusion, we have identified practice patterns and outcomes associated with choice of rate or rhythm control treatments for AF during sepsis. Our results suggest wide practice pattern variation across hospitals in selection of AF treatments during sepsis. Although CCBs were the most commonly selected initial IV treatment of AF during sepsis, BBs were associated with superior survival in all subgroups analyzed. Our findings provide strong rationale for randomized clinical trials comparing the effectiveness AF treatments during sepsis.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: A. J. W. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including data and analysis. A. J. W. contributed to study conception, design, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript; S. R. E. and M. R. W. contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and editing of manuscript for intellectual content; E. J. B. contributed to study design, interpretation, and editing of manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial/nonfiancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants K01HL116768 (A. J. W.) and 2R01HL092577 (E. J. B.)].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Walkey A.J., Lagu T., Lindenauer P.K. Trends in sepsis and infection sources in the United States. A population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(2):216–220. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-498BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu V., Escobar G.J., Greene J.D. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walkey A.J., Greiner M.A., Heckbert S.R. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949–955.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walkey A.J., Benjamin E.J., Lubitz S.A. New-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(22):2432–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annane D., Sébille V., Duboc D. Incidence and prognosis of sustained arrhythmias in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(1):20–25. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-031OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walkey A.J., Wiener R.S., Ghobrial J.M., Curtis L.H., Benjamin E.J. Incident stroke and mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306(20):2248–2254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salman S., Bajwa A., Gajic O., Afessa B. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients with sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23(3):178–183. doi: 10.1177/0885066608315838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christian S.A., Schorr C., Ferchau L., Jarbrink M.E., Parrillo J.E., Gerber D.R. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of septic patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation. J Crit Care. 2008;23(4):532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman S., Shirov T., Weissman C. Supraventricular arrhythmias in intensive care unit patients: short and long-term consequences. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(4):880–886. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255759.41131.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walkey A.J., Hammill B.G., Curtis L.H., Benjamin E.J. Long-term outcomes following development of new-onset atrial fibrillation during sepsis. Chest. 2014;146(5):1187–1195. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.January C.T., Wann L.S., Alpert J.S., American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayr A., Ritsch N., Knotzer H. Effectiveness of direct-current cardioversion for treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, in particular atrial fibrillation, in surgical intensive care patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(2):401–405. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000048627.39686.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delle Karth G., Geppert A., Neunteufl T. Amiodarone versus diltiazem for rate control in critically ill patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(6):1149–1153. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang E.L., Chan W.L., Cleland J.G. Placebo controlled trial of xamoterol versus digoxin in chronic atrial fibrillation. Br Heart J. 1990;64(4):256–260. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.4.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gheorghiade M., Adams K.F., Jr., Colucci W.S. Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2004;109(24):2959–2964. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132482.95686.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou Z.Y., Chang M.S., Chen C.Y. Acute treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter with a tailored dosing regimen of intravenous amiodarone. A randomized, digoxin-controlled study. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(4):521–528. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanji S., Stewart R., Fergusson D.A., McIntyre L., Turgeon A.F., Hébert P.C. Treatment of new-onset atrial fibrillation in noncardiac intensive care unit patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(5):1620–1624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181709e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwashyna T.J., Odden A., Rohde J. Identifying patients with severe sepsis using administrative claims: patient-level validation of the angus implementation of the international consensus conference definition of severe sepsis. Med Care. 2014;56(6):e39–e43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268ac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen P.N., Johnson K., Floyd J., Heckbert S.R., Carnahan R., Dublin S. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying atrial fibrillation using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):141–147. doi: 10.1002/pds.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum P.R., Rubin D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston S.C., Henneman T., McCulloch C.E., van der Laan M. Modeling treatment effects on binary outcomes with grouped-treatment variables and individual covariates. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(8):753–760. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merlo J., Chaix B., Ohlsson H. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290–297. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein H., Browne W., Rasbash J. Multilevel modelling of medical data. Stat Med. 2002;21(21):3291–3315. doi: 10.1002/sim.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seymour C.W., Iwashyna T.J., Ehlenbach W.J., Wunsch H., Cooke C.R. Hospital-level variation in the use of intensive care. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):2060–2080. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olshansky B., Rosenfeld L.E., Warner A.L., AFFIRM Investigators The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study: approaches to control rate in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(7):1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooss A.N., Wurdeman R.L., Mohiuddin S.M. Esmolol versus diltiazem in the treatment of postoperative atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter after open heart surgery. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):176–180. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balser J.R., Martinez E.A., Winters B.D. Beta-adrenergic blockade accelerates conversion of postoperative supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(5):1052–1059. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platia E.V., Michelson E.L., Porterfield J.K., Das G. Esmolol versus verapamil in the acute treatment of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(13):925–929. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sticherling C., Tada H., Hsu W. Effects of diltiazem and esmolol on cycle length and spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2002;7(2):81–88. doi: 10.1177/107424840200700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morelli A., Ertmer C., Westphal M. Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1683–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morelli A., Donati A., Ertmer C. Microvascular effects of heart rate control with esmolol in patients with septic shock: a pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9):2162–2168. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a678d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ibrahim-Zada I., Rhee P., Gomez C.T., Weller J., Friese R.S. Inhibition of sepsis-induced inflammatory response by β1-adrenergic antagonists. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):320–327. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori K., Morisaki H., Yajima S. Beta-1 blocker improves survival of septic rats through preservation of gut barrier function. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(11):1849–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouyang A.J., Lv Y.N., Zhong H.L. Meta-analysis of digoxin use and risk of mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(7):901–906. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pastori D., Farcomeni A., Bucci T. Digoxin treatment is associated with increased total and cardiovascular mortality in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2015;180:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turakhia M.P., Santangeli P., Winkelmayer W.C. Increased mortality associated with digoxin in contemporary patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the TREAT-AF study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(7):660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitbeck M.G., Charnigo R.J., Khairy P. Increased mortality among patients taking digoxin–analysis from the AFFIRM study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(20):1481–1488. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaughan-Sarrazin M.S., Mazur A., Chrischilles E., Cram P. Trends in the pharmacologic management of atrial fibrillation: data from the Veterans Affairs health system. Am Heart J. 2014;168(1):53–59.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran J.L., Gallagher J., Peake S.L., Cunningham D.N., Salagaras M., Leppard P. Parenteral magnesium sulfate versus amiodarone in the therapy of atrial tachyarrhythmias: a prospective, randomized study. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(11):1816–1824. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagu T., Lindenauer P.K., Rothberg M.B. Development and validation of a model that uses enhanced administrative data to predict mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(11):2425–2430. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822572e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.