The potential of bendamustine, a purine-like alkylating agent, for treating blood cancers associated with the Epstein-Barr virus led us to examine interactions between drug and virus. Bendamustine and other alkylating agents such as chlorambucil and melphalan disrupt latency. Bendamustine and rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, can combine to increase lytic replication. We discuss how this ability to reactivate latent virus informs clinical strategies.

The human Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is associated with hematologic malignancies. This herpesvirus evades immune surveillance over the host’s lifetime by entering a quiescent phase in B cells. Compared to lytic replication, during which ~100 gene products amplify virus, latency restricts transcription to ~1–10 genes [1]. EBV adopts this expression program to immortalize B cells in vitro and inhabit tumors of B cell malignancies like a proportion of Burkitt, Hodgkin, post-transplantation, diffuse large B cell, primary central nervous system, primary effusion, and plasmablastic lymphoma in vivo [1,2].

Bendamustine is a chemotherapy agent increasingly used to treat blood cancers. Recently rediscovered, this small molecule contains a mechlorethamine nitrogen mustard that generates DNA damage distinct from other alkylating drugs. Bendamustine combined with other drugs [3,4] effectively treats indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Preliminary trials also show success against relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma [5,6]. Similarly aggressive cancers are associated with EBV infection [1,2], so the potential of bendamustine treatment for EBV-associated malignancies led us to examine interactions between drug and virus.

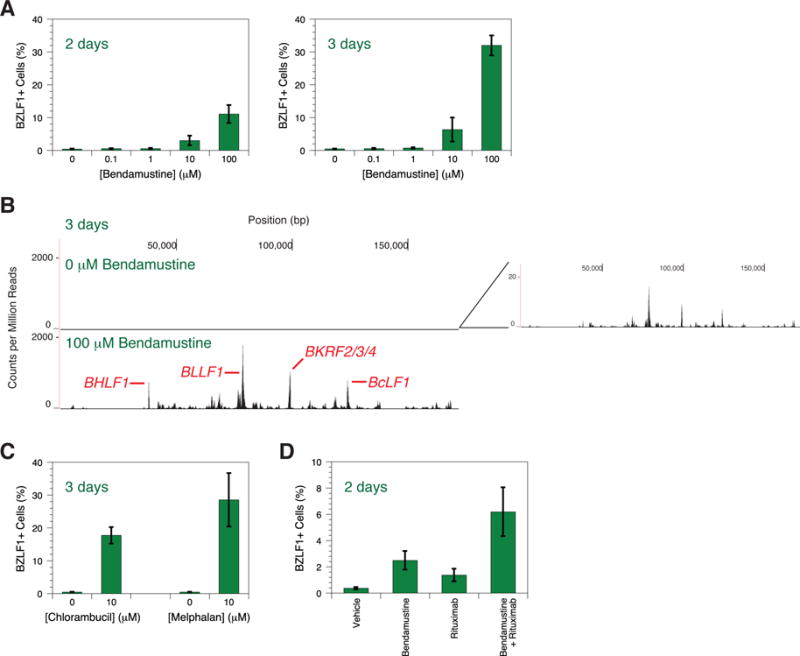

Bendamustine and other alkylating chemotherapy drugs induce EBV reactivation in a cell culture model of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. MutuI cells [7] were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 containing 2 mM HEPES and 10% fetal bovine serum. We treated cells at a density of 0.5×10ˆ6/mL with bendamustine (Sigma-Aldrich or Millipore). Reactivation was measured by staining for the immediate-early lytic transactivator BZLF1 using the paraformaldehyde-methanol method [8] with a BZ1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCaliburDxP8 (B.D. Biosciences). Bendamustine evokes both a dose- and time-dependent response in that 2- or 3- day treatment with 10–100 μM bendamustine induces ~10–30% reactivation (Figure 1A). Lytic induction also modestly occurs in EBV-infected Akata and Daudi cells, but not detectably in KemI, KemIII, and GM12878 cells (data not shown). Deep sequencing of the EBV transcriptome (Phan and Miranda, submitted) reveals that bendamustine increases RNA levels genome-wide by ~100-fold (Figure 1B). BHLF1 shares a promoter with the lytic origin of replication and its expression correlates with reactivation [9]; BcLF1, a true late gene, requires viral DNA replication to encode a capsid protein [10]. Bendamustine increases BHLF1 and BcLF1 expression as well as the entire lytic program. Curious if other alkylating agents have similar effects, we treated cells with either 10 μM chlorambucil (Sigma-Aldrich) or 10 μM melphalan (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 days. Both drugs also reactivate EBV (Figure 1C). We can therefore add bendamustine and other alkylators to the list of DNA-damaging agents, such as cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, and doxorubicin [11,12], capable of disrupting EBV latency.

FIG 1.

EBV reactivation induced by bendamustine and other alkylating agents. (A) Time- and dose-dependent response of EBV reactivation upon bendamustine treatment. BZLF1 expression in MutuI cells was measured by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the standard deviation of n = 4 replicates. (B) Deep sequencing of the EBV transcriptome in response to bendamustine treatment. The X axis denotes nucleotide position and the Y axis denotes the number of counts per million mapped reads. An inset of the top panel depicts low levels of transcription not visible on the scale used to compare conditions. Specific lytic genes are annotated. One representative experiment from two independent replicates is shown. (C) EBV reactivation upon chlorambucil and melphalan treatment. BZLF1 expression in MutuI cells was measured by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the standard deviation of n = 4 replicates. (D) Increased reactivation induced by bendamustine plus rituximab. BZLF1 expression in MutuI cells was measured by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the standard deviation of n = 4 replicates.

Because bendamustine plus rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, effectively treats indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma [3,4], we investigated this combination’s interaction with latent EBV. 100 μg/mL rituximab and 10 μM bendamustine independently induce EBV reactivation after 2 days, but combination generates even more (Figure 1D). Rituximab similarly enhances reactivation induced by dexamethasone [13]. CD20 engagement combined with other latency disruptors may be a general means of enhancing induction.

The ability of bendamustine to reactivate latent EBV informs future clinical strategies. Taken pessimistically, our work warns that drug treatment may exacerbate risk of adverse effects caused by viremia in an already weakened immune system. Impairment of lymphocyte recovery by bendamustine [14] particularly warrants heightened precautions. Personalised medicine that tailors chemotheraphy regimens to EBV status of the tumor may suggest the preferred treatment. Taken optimistically, this study contends that bendamustine may be useful in lytic induction therapy, an alternative to standard cytotoxic treatment that attempts to leverage the presence of virus to target cancer cells. Latent EBV coerced into reactivation can specifically mark tumor cells for killing by cytopathic effects, epitope recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes, or small molecule drugs that target lytic proteins [15]. Our transcriptome profiling reveals that bendamustine induces the lytic EBV expression program, including true late genes, which demonstrates that prerequisite proteins must have been translated. These early proteins comprise the targets for multiple cure strategies. Drugs like bendamustine and other alkylating agents, which are already efficacious antitumor agents, could form the foundation of effective lytic induction therapy combinations. In whatever way this knowledge is applied, future clinical work should recognize that bendamustine reactivates latent EBV.

Acknowledgments

We thank An T. Phan for optimizing the BZLF1 expression assay, Shannon C. Kenney (University of Wisconsin, Madison) for providing the MutuI cell line, and Marielle Cavrois and Marianne L. Gesner at the Gladstone Institutes Flow Cytometry Core for assisting with experiments. This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. This publication was made possible with help from the University of California San Francisco-Gladstone Institute of Virology & Immunology Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI027763).

References

- 1.Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nature reviews Cancer. 2004;4(10):757–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbone A, Cesarman E, Spina M, Gloghini A, Schulz TF. HIV-associated lymphomas and gamma-herpesviruses. Blood. 2009;113(6):1213–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, Banat GA, von Grunhagen U, Losem C, Kofahl-Krause D, Heil G, Welslau M, Balser C, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, Wood P, Hawkins TE, Macdonald D, Hertzberg M, Kwan YL, Simpson D, Craig M, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-531327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohmachi K, Niitsu N, Uchida T, Kim SJ, Ando K, Takahashi N, Uike N, Eom HS, Chae YS, Terauchi T, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bendamustine plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(17):2103–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vacirca JL, Acs PI, Tabbara IA, Rosen PJ, Lee P, Lynam E. Bendamustine combined with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Annals of hematology. 2014;93(3):403–9. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory CD, Rowe M, Rickinson AB. Different Epstein-Barr virus-B cell interactions in phenotypically distinct clones of a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line. The Journal of general virology. 1990;71(Pt 7):1481–95. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imbert-Marcille BM, Coste-Burel M, Robillard N, Foucaud-Gamen J, Billaudel S, Drouet E. Sequential use of paraformaldehyde and methanol as optimal conditions for the direct quantification of ZEBRA and rta antigens by flow cytometry. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2000;7(2):206–11. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.206-211.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arvey A, Tempera I, Tsai K, Chen HS, Tikhmyanova N, Klichinsky M, Leslie C, Lieberman PM. An atlas of the Epstein-Barr virus transcriptome and epigenome reveals host-virus regulatory interactions. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12(2):233–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang PJ, Chang YS, Liu ST. Characterization of the BcLF1 promoter in Epstein-Barr virus. The Journal of general virology. 1998;79(Pt 8):2003–6. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-8-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng WH, Israel B, Raab-Traub N, Busson P, Kenney SC. Chemotherapy induces lytic EBV replication and confers ganciclovir susceptibility to EBV-positive epithelial cell tumors. Cancer research. 2002;62(6):1920–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng WH, Hong G, Delecluse HJ, Kenney SC. Lytic induction therapy for Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphomas. Journal of virology. 2004;78(4):1893–902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1893-1902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daibata M, Bandobashi K, Kuroda M, Imai S, Miyoshi I, Taguchi H. Induction of lytic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection by synergistic action of rituximab and dexamethasone renders EBV-positive lymphoma cells more susceptible to ganciclovir cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Journal of virology. 2005;79(9):5875–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5875-5879.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia Munoz R, Izquierdo-Gil A, Munoz A, Roldan-Galiacho V, Rabasa P, Panizo C. Lymphocyte recovery is impaired in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine plus rituximab. Annals of hematology. 2014;93(11):1879–87. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israel BF, Kenney SC. Virally targeted therapies for EBV-associated malignancies. Oncogene. 2003;22(33):5122–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]