Abstract

Proton transfer is integral to many biochemical processes. However, the direct observation and structural characterization of biological proton transfer has hitherto not been possible. Here, neutron crystallography directly locates two protons before and after a pH-induced two-proton transfer between the catalytic aspartic acid residues and the hydroxyl group of the bound clinical drug, darunavir, in the catalytic site of enzyme HIV-1 protease. The two-proton transfer is triggered by electrostatic effects arising from protonation state changes of surface residues far from the active site. The mechanism and pH effect are supported by QM/MM calculations. We propose that the low-pH proton configuration in the catalytic site is critical for the catalytic action of this enzyme and may apply more generally to other aspartic proteases. Neutrons therefore represent a superb probe to obtain structural details for proton transfer reactions in biological systems at a truly atomic level.

Keywords: proton transfer, macromolecular neutron crystallography, QM/MM, enzyme, aspartic protease

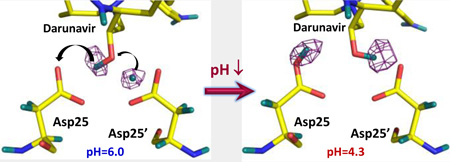

Graphical abstract

Neutron crystallography captures a two-proton transfer in the HIV-1 protease catalytic site triggered by changes in protonation states of distant amino acid side chains.

Proton transfer in aqueous solution is a fundamental chemical reaction that is at the heart of ion channel function and most enzymatic reactions.[1–5] Protonsareoften relayed between protein residues, water molecules and substrates. The relay mechanism, or proton “hopping”, first proposed by Grotthuss[6,7] to explain the anomalously high proton mobility in water, is a generally accepted mechanism for sequential proton transfer in aqueous media.

Direct observation of proton transfer in chemical and biological systems is challenging because reaction products may be unstable, or the transferred proton may be exported to the bulk solvent. Hence, ultrafast pump-probe spectroscopic methods such as femtosecond infrared spectroscopy have been used, for example, to follow the transfer of an acidic hydroxyl (OH) proton from a photolabile acid to acetic acid and its derivatives, and even to human serum albumin.[8–11] Similarly, excited-state proton transfer has been studied in green fluorescent protein (GFP), mapping the pathway of the proton hopping from the fluorophore OH to a glutamate side chain through a water molecule and a serine residue.[12–14] However, in these examples the proton is transferred back to the OH group once the photoacids return to the ground state and regain their initial acidities.

Unequivocal description of proton transfer mechanisms requires crystallographic experiments on both the reactant and product states. X-rays are scattered by electrons; thus, X-ray scattering power increases with atomic number. The smallest atom, hydrogen (H) with only one electron, is therefore hard to visualize with X-ray crystallography. Accordingly, the most biologically interesting H atoms are generally unobserved in electron density maps,[15] even at sub-Å resolution, as exemplified by GFP.[16] Moreover, highly polarized H atoms, having little electron density, and electron-bare protons (H+) are fundamentally invisible to X-rays. Consequently, no X-ray structural studies have directly observed H atoms in biomacromolecules before and after a proton transfer reaction has occurred. In contrast to X-rays, neutrons are scattered by atomic nuclei. The coherent neutron scattering lengths of H and deuterium, D, are similar in magnitude to those of other atoms found in biomacromolecules. Thus, locating H and D atoms and H+/D+ ions in macromolecular neutron structures is straightforward, even at resolutions as low as 2.0–2.5 Å.

Macromolecular neutron crystallography (MNC) has been instrumental in answering long-standing questions about enzyme mechanisms[17–19] and ligand binding.[20,21] For example, neutron structures have revealed hydrated protons (or hydronium, H3O+), which exist only transiently in bulk water, bound within proteins,[22–24] and have provided indisputable evidence of low-barrier hydrogen bonds in enzyme active sites.[22,25] MNC is hence the method of choice for unequivocal determination of the positions of H and D atoms in biomacromolecules.[26] Here, we demonstrate, for the first time, that MNC can be used to directly determine hydrogen atom positions in the reactant and product states of a proton transfer reaction, i.e. before and after proton transfer. We provide compelling evidence for a two-proton transfer in the confined environment of an enzyme active site in a crystal. Moreover, the proton transfer is found to be triggered by long-range electrostatic effects of surface residues undergoing protonation changes due to pH.

HIV-1 protease, an aspartic protease, is a key drug target for HIV/AIDS therapy. Understanding its structure and function at the atomic level, including the location and movement of H atoms, is vital for understanding drug resistance and guiding rational drug design.[27,28] Aspartic proteases catalyze the hydrolysis of peptide bonds by using two closely co-located aspartic acid (Asp) residues (Figure 1). The conventional mechanism for aspartic proteases involves general acid/base catalysis, with one protonated Asp carboxylic side chain (COOH) acting as a general acid to donate a proton to the carbonyl oxygen of the scissile peptide bond and the other, deprotonated Asp carboxylate (COO−) playing the role of the general base to abstract a proton from the catalytic H2O.[29] Thus, in the substrate-free form, the catalytic Asp dyad is mono-protonated and bound to an H2O molecule.[30,31]Quantum chemical calculations have placed the proton between the inner Oδ1 oxygen atoms of the catalytic Asp residues symmetrically in a low-barrier hydrogen bond, with the catalytic H2O also symmetrically hydrogen-bonded to the two outer Oδ2 oxygens (Figure 2).[32,33] The symmetrical hydrogen bonds must be broken for protease activity, and the proton transferred from the inner to the outer oxygen of the Asp. It has been proposed that this process is driven either by substrate binding or by the conformational dynamics of the flap region, a flexible hairpin structure that covers the active site (Figure 1).[31,32]

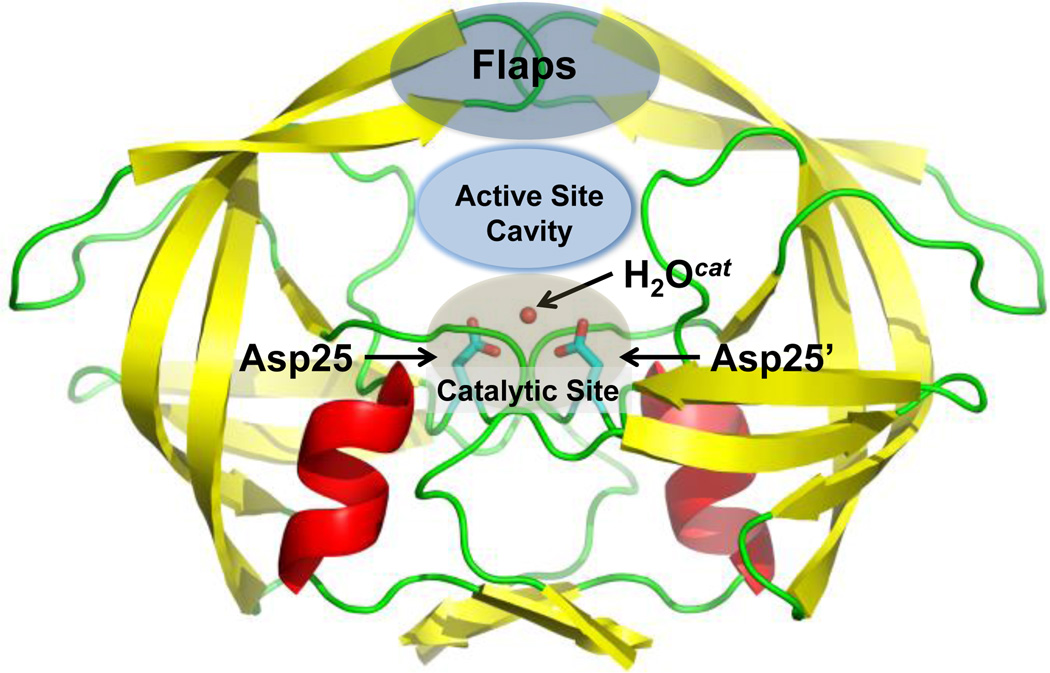

Figure 1.

Substrate-free HIV-1 protease showing catalytic Asp25 and Asp25’ residues and the lytic water molecule. Figure generated from PDB entry 2PC0.

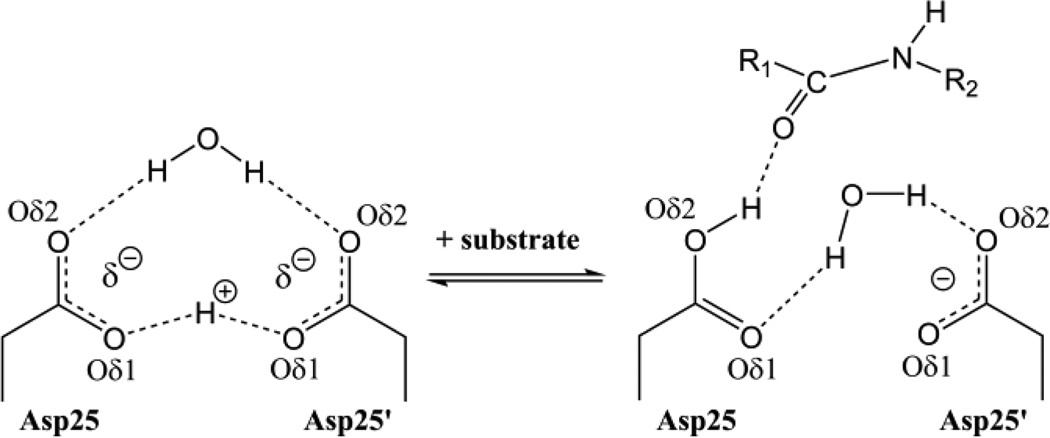

Figure 2.

Proposed hydrogen bonding in the catalytic site of substrate-free HIV-1 protease and its rearrangement upon substrate binding. How the proton shifts from the inner Oδ1 oxygen atoms to the outer Oδ2 of the catalytic Asp residue is a matter of debate.

To directly visualize H atoms (observed as D) in the catalytic site of an aspartic protease before and after proton transfer, we determined room-temperature neutron structures of perdeuterated HIV-1 protease in complex with the clinical drug darunavir at pH 6.0 and 4.3 to resolutions of 2.0 and 2.3 Å, respectively. The omit difference FO-FC neutron scattering length density map for the catalytic site in the complex obtained at pH 6.0 indicates that D1 of the catalytic dyad is D+ located equidistantly between the carboxylate of Asp25’ and the OH of darunavir, with all D⋯O distances being 1.5–1.6 Å (Figure 3 and Figs. S1, S2). The position of D+ implies that it is shared by the three oxygen atoms, suggesting possible formation of a low-barrier hydrogen bond. The OH group of the drug faces Asp25, making a bifurcated hydrogen bond with both carboxylic oxygen atoms (D⋯O distances of 2.0 Å). The locations of the D atoms in this structure differ from those observed in our recent neutron structure of wild-type HIV-1 protease in complex with amprenavir at pH 6.0, in which the carboxylic D is bound to the inner Oδ1 of Asp25, and the hydroxyl D of amprenavir is oriented toward the outer Oδ2 of Asp25’ (Figure S2)[34] with both D atoms involved in short, but conventional, strong hydrogen bonds, with D⋯O distances of 1.5 and 1.7 Å.

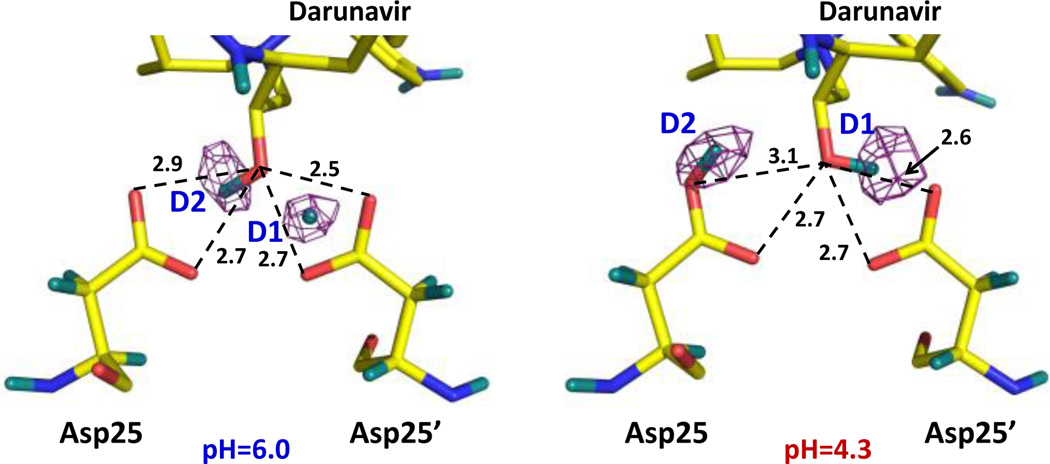

Figure 3.

Omit FO-FC difference (purple mesh) neutron scattering length density maps (contoured at 3.0 σ) for the HIV-1 protease catalytic site at pH 6.0 (left) and pH 4.3 (right).A two-proton transfer has occurred; i.e. D1 on Asp25’ has moved to the OH of darunavir and D2 has been transferred to Asp25. D atoms are coloured teal, and H atoms of darunavir are omitted for clarity. Distances are in Å.

In the neutron structure at pH 4.3, four surface residues – Asp30, Asp30’, Glu34 and Glu34’ – each gained a proton (Figure S3), but no other changes in protonation states were observed. Furthermore, D1 and D2 in the active site occupy different positions from those in the pH 6.0 structure (Figure 3). In the pH 4.3 structure, Asp25 is protonated on the outer Oδ2 oxygen, whereas the OH group of darunavir now hydrogen bonds with Asp25’. Therefore, a net two-proton transfer has occurred between the catalytic Asp residues and the OH of the drug. This transfer was triggered by changes in the electrostatic properties of the protein resulting from the protonation of the four surface residues. The electrostatic changes occur relatively far away (11–14 Å) from the catalytic site (Figure S4). Because the catalytic site is not accessible to water when an inhibitor is bound, we can deduce the proton transfer pathway. D1 is transferred to the darunavir oxygen, while D2 shifts to Asp25. At low pH, D1 forms a short, strong hydrogen bond with the outer Oδ2 of Asp25’ (D⋯O distance = 1.6 Å), but D2 makes only a weak interaction with the darunavir hydroxyl oxygen (D⋯O distance = 2.5 Å), similar to the previously determined pH 4.6 structure of HIV-1 protease complexed with an inhibitor.[35] Importantly, although the D atoms are found in disparate arrangements, the relative positions of the oxygens and corresponding O⋯O distances between Asp25, Asp25’ and darunavir remain essentially unchanged between the two neutron structures and are also very similar to those in the HIV-1 protease-amprenavir complex (Figure 3 and S2).[34] Consequently, our neutron structures show that proton positions and hydrogen bonding interactions cannot always be deduced correctly merely on the basis of O⋯O distances in X-ray structures. Indeed, the positions of D atomsin these structures are different from the H atom locations inferred from the atomic-resolution X-ray structures of the protease V82A mutant in complex with a peptidic inhibitor or with darunavir.[36,37] In those X-ray structures, it was incorrectly proposed that H+ ions may have been observed in the catalytic site. Recently, similar claims of the observation of H+ ions in ultra-high resolution X-ray structures of proteins have been made,[38,39] but those claims should be treated with extreme caution as H+, with virtually no electron density around it, should not be visible in electron density maps.

To obtain further insight into the effect of the change in pH on the active site proton transfers, we computed potential energy profiles with a QM/MM approach on models derived from the two neutron structures. Calculations on the pH 6.0 model favour a configuration with the inner Asp25’ oxygen protonated and with the darunavir OH hydrogen bonded to the outer Asp25 oxygen (reactant, R, in Fig S5A). Concerted proton transfers to their respective hydrogen bonded partners indicate a low barrier of 5.0 kcal mol−1 (Figure S5A). A low potential energy barrier with the inclusion of zero-point energy[33] of ~2 kcal mol−1 is consistent with the observation from neutron crystallography of a shared proton between Asp25’ and darunavir. When the Asp25’ proton was instead placed on the outer oxygen of Asp25’, it transferred spontaneously to the darunavir hydroxyl, the proton of which transfers to the Asp25 inner oxygen, resulting in a configuration resembling the amprenavir-bound structure (Figure S2).[34] The favoured pH 6.0 configuration also predominated in a QM/MM molecular dynamics simulation, though the trajectory also sampled geometries consistent with the Asp25’ proton shared with darunavir (Figure S5B). In analogous calculations on the pH 4.3 model and in contrast to the calculations on the pH 6.0 model, a stable minimum was found with the outer Asp25’ oxygen protonated and the darunavir OH hydrogen bonded to the outer Asp25 oxygen (reactant, R, in Figure S5C). Calculated concerted proton transfers to their respective hydrogen bonded partners to obtain a pH 4.3 neutron structure-like configuration indicates a barrier of ~4 kcal mol−1 and a stable minimum for the pH 4.3 neutron structure-like configuration (Figure S5C and S5D). Overall, the calculations support the observations from neutron crystallography and are consistent with the proton transfers triggered primarily by a change in long-range electrostatics from the change in protonation states of the four surface residues.

In the present study, we have directly observed the induction of changes in H atom positions in the catalytic site of an enzyme by protonation of distant surface residues. This two-proton transfer in HIV-1 protease results in a proton shift from the inner to the outer carboxylic oxygens of the catalytic Asp dyad, a configuration that is essential for catalysis[29,31,32] and is apparently stable only when surface residues Asp30, Asp30’, Glu34, and Glu34’ are protonated (Figure S6). Protonation of the surface residues may be vital to the enzyme catalytic cycle, including its maturation from the precursor Gag-Pol.[40,41] More generally, we have demonstrated that neutron crystallography can reveal the positions of protons before and after transfer in biological systems, thus opening a new field of high-precision mechanistic analysis of biomacromolecular function.

Experimental Section

Experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 5E5J for HIV-1 triple mutant/darunavir complex at pH 6.0 and 5E5K for the complex at pH 4.3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Structural Molecular Biology (CSMB) at ORNL, supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER), for facility use. OG, PL and AK were partly supported by DOE BES. IW was partly supported by NIH grant R01GM02920. The authors thank Institut Laue Langevin (beamline LADI-III) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (IMAGINE beamline) for neutron beam time.

References

- 1.Kluger R. In: Enzyme Chem. Suckling CJ, editor. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1984. pp. 8–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munson K, Garcia R, Sachs G. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5267–5284. doi: 10.1021/bi047761p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Ballmoos C, Dimroth P. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11800–11809. doi: 10.1021/bi701083v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morii M, Yamauchi M, Ichikawa T, Fujii T, Takahashi Y, Asano S, Takeguchi N, Sakai H. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16876–16884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padan E, Rimon A, Tzubery T, Mueller M, Herz K, Galili L. In: Sodium-Hydrogen Exchanger. Karmazyn M, Avkiran M, Fliegel L, editors. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grotthuss CJT. Ann. Chim. 1806;LVIII:54–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marx D, Tuckermann ME, Hutter J, Parrinello M. Nature. 1999;397:601–604. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rini M, Magnes B-Z, Pines E, Nibbering ETJ. Science. 2003;301:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1085762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammed OF, Pines D, Dreyer J, Pines E, Nibbering ETJ. Science. 2005;310:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1117756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timmer RLA, Cox MJ, Bakker HJ. J. Phys. Chem A. 2010;114:2091–2101. doi: 10.1021/jp908561h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen B, Alvarez CM, Carmona NA, Organero JA, Douhal A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:7637–7647. doi: 10.1021/jp200294q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoner-Ma D, Jaye AA, Matousek P, Towrie M, Meech SR, Tonge PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2864–2865. doi: 10.1021/ja042466d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaucikas M, Tros M, van Thor JJ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:2350–2362. doi: 10.1021/jp506640q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laptenok SP, Lukacs A, Gil A, Brust R, Sazanovich IV, Greetham GM, Tonge PJ, Meech SR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:9303–9307. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blakeley MP, Hasnain SS, Antonyuk SV. IUCR J. 2015;2:464–474. doi: 10.1107/S2052252515011239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinobu A, Palm GJ, Schierbeek AJ, Agmon N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11093–11102. doi: 10.1021/ja1010652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovalevsky AY, Hanson L, Fisher SZ, Mustyakimov M, Mason SA, Forsyth VT, Blakeley MP, Keen DA, Wagner T, Carrell HL, Katz AK, Glusker JP, Langan P. Structure. 2010;18:688–699. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casadei CM, Gumiero A, Metcalfe CL, Murphy EJ, Basran J, Concilio MG, Teixeira SCM, Schrader TE, Fielding AJ, Ostermann A, Blakeley MP, Raven EL, Moody PCE. Science. 2014;345:193–197. doi: 10.1126/science.1254398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan Q, Bennett BC, Wilson MA, Kovalevsky A, Langan P, Howell EE, Dealwis C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:18225–18230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415856111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett B, Langan P, Coates L, Mustyakimov M, Schoenborn B, Howell EE, Dealwis C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18493–18498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomanicek SJ, Standaert RF, Weiss KL, Ostermann A, Schrader TE, Ng JD, Coates L. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:4715–4722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovalevsky AY, Hanson BL, Mason SA, Yoshida T, Fisher SZ, Mustyakimov M, Forsyth VT, Blakeley MP, Keen DA, Langan P. Angew. Chem. –Int. Ed. 2011;50:7520–7523. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuypers MG, Mason SA, Blakeley MP, Mitchell EP, Haertlein M, Forsyth VT. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1022–1025. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unno M, Ishikawa-Suto K, Kusaka K, Tamada T, Hagiwara Y, Sugishima M, Wada K, Yamada T, Tomoyori K, Hosoya T, Tanaka I, Niimura N, Kuroki R, Inaka K, Ishihara M, Fukuyama K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:5452–5460. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi S, Kamikubo H, Kurihara K, Kuroki R, Niimura N, Shimizu N, Yamazaki Y, Kataoka M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:440–444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811882106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niimura N, Podjarny A. Neutron Protein Crystallography. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011. p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber IT, Wang Y-F. In: Aspartic Proteases as Therapeutic Targets. Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry. Ghosh AK, editor. Vol. 45. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2010. pp. 109–137. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber IT, Kneller DW, Wong-Sam A. Future Med. Chem. 2015;7:1023–1038. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjelic S, Åqvist J. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7709–7723. doi: 10.1021/bi060131y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu. Torbeev V, Kent SB. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:5887–5891. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25569c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu. Torbeev V, Raghuraman H, Hamelberg D, Tonelli M, Westler WM, Perozo E, Kent SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20982–20987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111202108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piana S, Bucher D, Carloni P, Rothlisberger U. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:11139–11149. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porter MA, Molina PA. J. Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:1675–1684. doi: 10.1021/ct600200s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber IT, Waltman MJ, Mustyakimov M, Blakeley MP, Keen DA, Ghosh AK, Langan P, Kovalevsky AY. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:5631–5635. doi: 10.1021/jm400684f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adachi M, Ohhara T, Kurihara K, Tamada T, Honjo E, Okazaki N, Arai S, Shoyama Y, Kimura K, Matsumura H, Sugiyama S, Adachi H, Takano K, Mori Y, Hidaka K, Kimura T, Hayashi Y, Kiso Y, Kuroki R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4641–4646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809400106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brynda J, Rezacova P, Fabry M, Horejsi M, Stouracova R, Sedlacek J, Soucek M, Hradilek M, Lepsik M, Konvalinka J. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2030–2036. doi: 10.1021/jm031105q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tie Y, Boross PI, Wang Y-F, Gaddis L, Hussain AK, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogata H, Nishikawa K, Lubitz W. Nature. 2015;520:571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature14110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nichols DA, Hargis JC, Sanishvili R, Jaishankar P, Defrees K, Smith EW, Wang KK, Prati F, Renslo AR, Woodcock HL, Chen Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:8086–8095. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyland LJ, Tomaszek TA, Jr, Meek TD. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8454–8463. doi: 10.1021/bi00098a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Louis JM, Ishima R, Torchia DA, Weber IT. Adv. Pharmacol. 2007;55:261–298. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)55008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.