Abstract

Objective

To date, no measure of social support has been developed specifically for either palliative care or oncology settings. The present study examined the psychometric properties of the Duke–University of North Carolina Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS) in order to (1) assess the adequacy of the scale in the context of severe medical illness and (2) evaluate whether a brief subset of items might generate roughly comparable utility.

Method

The 14-item DUFSS was administered to 1,362 individuals with advanced cancer or AIDS. Classical test theory (CTT) and item response theory (IRT) analyses were utilized to develop an abbreviated version of the DUFSS that maintained adequate reliability and validity and might increase the feasibility of its administration in a palliative care setting. The reliability and concurrent validity of the DUFSS-5 were evaluated in a separate validation sample of patients with advanced cancer.

Results

Analyses generated a five-item version of the DUFSS (the DUFSS-5) that collapsed response levels into only three options, instead of five. Correlations between the DUFSS-5 and measures of depression, quality of life, and desire for hastened death, as well as regression models testing the main-effect and buffering models of social support, provided support for the utility of the DUFSS-5.

Significance of results

Both the DUFSS and the abbreviated DUFSS-5 appear to have adequate reliability and validity in this setting. Moreover, the DUFSS-5 represents a potentially important option for healthcare researchers, particularly for those working in palliative care settings where issues of patient burden are paramount. Such analyses are critical for advancing the development and refinement of psychosocial measures, but have often been neglected.

Keywords: Social support, Palliative care, Item response theory

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that individuals who have supportive interpersonal relationships are healthier than those without such ties (Barth et al., 2010; Cohen & Wills, 1985; DiMatteo, 2004; Eom et al., 2012; Uchino et al., 1996). Theories of social support cite multiple possible sources—including emotional, informational, social companionship, and instrumental support—all of which tend to be correlated with one another (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Although numerous measures of social support have been developed and applied over the past few decades, the general finding that stronger social support networks are beneficial has remained relatively constant.

Two primary models have been proposed to explain the role of social support in promoting well-being: the “main-effect” model and the “buffering” model. The main-effect model posits that social support has a beneficial effect on well-being regardless of stress level. Cohen and Wills (1985) postulated that a main effect of social support may occur because people who are embedded in strong social networks regularly experience positive events, such as a sense of stability and predictability and a recognition of their self-worth. Social networks may also help an individual avoid negative experiences that might otherwise cause distress (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The buffering model proposes that social support has an effect on well-being only when an individual is experiencing stress or adversity. It posits an interaction between stress and social support, whereby little impact for social support is observed when individuals are experiencing low levels of stress conditions, but as levels of stress increase a greater attenuation of adverse reactions (e.g., physical and/or psychological symptoms) occurs for those with higher levels of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Regardless of the underlying model, social support assessment tools typically fall into two categories: structural and functional measures. Structural measures are quantitative in nature and target social network size, frequency, or density. Functional measures, on the other hand, assess the extent to which relationships fulfill certain functional needs, including emotional, appraisal, informational, and instrumental support. Typically, structural measures assess the objective characteristics of social networks, while functional measures assess an individual's perceptions of available social support (Cohen & Syme, 1985; Uchino, 2009). Functional measures of social support also differ in the extent to which they focus on perceived support versus actual support received (e.g., amount of time or contact or number of people in one's social network; Vangelisti, 2009). Although considerable variability exists across studies, functional measures of perceived social support have generally proved to be stronger predictors of health and health behavior than structural measures or functional measures of actual support received (Broadhead et al., 1989; Cohen & Syme, 1985; DiMatteo, 2004; Orth-Gomér, Rosengren & Wilhelmsen, 1993; Uchino, 2009).

Social support has been extensively examined in relation to physical health, with studies focusing on illness onset, adaptation to illness, utilization of health services, treatment adherence, recovery and rehabilitation, and even mortality (Cohen & Syme, 1985; Kroenke et al., 2012; Uchino et al., 1996). For example, Kroenke and colleagues (2006) found that women with breast cancer who had few social supports were twice as likely to die from their illness than women who were integrated into a large social network. A recent meta-analysis of 104 studies (Pinquart & Duberstein, 2010) revealed significantly lower mortality rates in individuals with higher (vs. lower) levels of perceived social support (risk ratio = 0.82, CI95% = 0.75, 0.89, p < 0.0001), larger social networks (risk ratio = 0.80, CI95% = 0.72, 0.88, p < 0.0001), and married compared to nonmarried individuals (risk ratio = 0.87, CI95% = 0.84, 0.90, p < 0.0001).

Although the potential benefits of social support are well established in a wide range of medical illnesses, the role of social support in palliative care settings has been rarely studied. Hann and colleagues (1995), in their study of patients with metastatic cancer, found that perceived adequacy of social support, but not structural aspects of the social network (e.g., number of available supports), was significantly associated with lower levels of depression. Ringdal and coworkers (2007), in their study of patients with metastatic cancer who had an estimated survival time of two to nine months, found that participants with higher levels of emotional support reported fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those with lower levels of support. They postulated that emotional support may become more important than other types of support as patients get weaker and closer to death, and that the buffering effect of social support on emotional functioning continues to be important even during the last months of life.

Despite the apparent importance of social support, this literature is rife with measurement and methodological problems. There has been very little agreement on how to operationalize social support, and the models of social support proposed (i.e., main versus buffering effects) have received inconsistent support (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Uchino, 2009; Vangelisti, 2009). Many researchers contend that context-specific measures are needed in order to understand the mechanism of support in unique settings, illnesses, or patient populations (Cohen & McKay, 1984; Cohen & Syme, 1985). Furthermore, although many social support measures appear to have strong face validity, the psychometric properties of these measures are often poor or unreported (Cohen & Syme, 1985; Reis, 1984; Uchino et al., 1996). Given the importance of social support in mental and physical health, there is a need for systematic evaluation of the psychometric properties of social support measures in specific clinical populations, such as those with advanced or terminal illness.

To date, no measure of social support has been developed specifically for either palliative care or oncology settings. However, one scale that has been used in several studies of terminally ill cancer and AIDS patients is the Duke–University of North Carolina Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS; Broadhead et al., 1988). Originally developed to measure perceived social support in family medicine settings, the DUFSS has demonstrated significant associations with well-being in patients with advanced and terminal cancer (Breitbart et al., 2000; González et al., 2002), diabetes (Oren et al., 1996), and AIDS (Rosenfeld et al., 2006).

One complication with the DUFSS, as with many social support measures, is that different versions have been utilized in different studies. The original validation study published by Broadhead et al. (1988) presented a 14-item scale but reduced the scale to 8 items based on their initial validation study. However, an 11-item version of the DUFSS has also been utilized (Ahumada et al., 1991; Saameño et al., 1996), as has the complete 14-item scale (Breitbart et al., 2000; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). Because of the apparent utility of the DUFSS in varied clinical populations, as well as the importance of parsimony in constructing measurement tools—particularly when patient burden is already high—we sought to examine the psychometric properties of the DUFSS in patients with advanced and/or terminal illness.

METHODS

Participants

The present investigation utilized several samples of participants with advanced illness, some of which were used for the initial item analyses, and a new sample in which the reliability and validity of an abbreviated scale were explored.

Item Analysis Samples

The participants used in our initial psychometric analyses were recruited between January of 1999 and September of 2005 from five facilities as part of five different research studies (Breitbart et al., 2009; 2012; Olden et al., 2009; Rosenfeld et al., 2006; 2011). These studies all addressed end-of-life issues and were collapsed to form three subsamples. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS were recruited from two skilled nursing facilities and a palliative care hospital; terminally ill cancer patients were recruited from a palliative care hospital; and ambulatory patients with advanced cancer were recruited from a tertiary care cancer center. The total sample included 1,362 participants, with 384 AIDS patients, 591 hospitalized cancer patients in a palliative care hospital, and 387 ambulatory cancer patients. All participants were English speakers, over 18 years of age, and had scored above 20 on the Mini–Mental Status Exam (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975), indicating sufficient cognitive functioning to participate in the research studies. Patients were excluded if they were too ill or confused to complete MMSE screening or give informed consent.

The total sample was 61.7% male (n = 841) and 38% female (n = 518), with an average age of 57.5 years old (SD = 15, range = 20 to 96) and an average of 13.8 years of education completed (SD = 3.5). The sample was predominately Caucasian/Non-Hispanic (57.2%, n = 779), with roughly one third African American (28.4%, n = 387) and 10% Hispanic (n = 138). Within the sample, 35% were single (n = 477), 28.1% were married (n = 383), 14.5% widowed (n = 197), and 20% divorced or separated (n = 273). Among the cancer patients (n = 978), all had stage 3 or 4 disease, and the most common types of cancer were breast (10.3%), lung/bronchus (9%), colon (7.9%), and pancreas (7.2%). The remaining participants had a diagnosis of AIDS (28.2%, n = 384).

Validation Sample

Participants were recruited between August of 2007 and May of 2012 from an ambulatory care cancer center to participate in a psychotherapy research study for patients with advanced cancer. All participants were English speakers, over 18 years old, and had scored above 20 on the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975), indicating sufficient cognitive functioning to participate in the research study. The present study utilized the baseline assessment measures collected for these participants before they began participating in the psychotherapy research study.

The validation sample included 253 participants. The sample was 30.4% male (n = 77) and 69.6% female (n = 176), with an average age of 58.21 years old (SD = 10.98, range = 27–91) and an average of 15.9 years of education completed (SD = 2.5). The sample was predominately Caucasian (75.5%, n = 191), with roughly 14% African American (13.8%, n = 35) and 4.3% Asian (n = 11). Roughly 12% of the sample identified as Hispanic (11.9%, n = 30). Within the sample, half were married (n = 129), 21% divorced or separated (n = 53), 19% single (n = 48), and 6.7% widowed (n = 17). The most common types of cancer were breast (29.6%), pancreas (17.8%), lung/bronchus (15.8%), and colorectal (15.4%). The majority of participants had stage 4 disease (85.4%, n = 216), and the remainder had stage 3 diagnoses (13.8%, n = 35).

Procedures

After determining eligibility and providing written informed consent, participants in the item analysis sample were interviewed using a series of clinician-rated measures and completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. The assessment battery varied slightly across studies but typically included measures of depression, desire for hastened death, overall quality of life, pain and other physical symptoms, and social support. Only four measures were utilized in the present investigation (described below). Assessments typically took an hour and were completed over a single interview, but severely ill participants often required two or even three shorter sessions. In addition, measures were occasionally read aloud to patients who had significant fatigue problems or visual impairment.

The 14-item version of the Duke–UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS; Broadhead et al., 1988) was employed in this study because some of the items omitted in the 8-item version appeared to have strong face validity for a terminally ill sample (e.g., “I get visits from family and friends”). However, one item (“help around the house”) was changed to simply “help . . .” because most participants were hospitalized or residing in a skilled nursing facility, rendering the item meaningless for these individuals. The DUFSS asks participants to rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“much less than I would like”) to 4 (“as much as I would like”). Total scores range from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. In their validation study, the authors identified a two-factor structure to the scale corresponding to “confidant” (ability to share important information) and “affective” (emotional) support.

Participants in the validation sample also completed several self-report measures, including the Beck Depression Inventory, revised (BDI–II; Beck et al., 1996), the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQoL; Cohen et al., 1995), the Schedule of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD; Rosenfeld et al., 1999), and the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS; Portenoy et al., 1994). The BDI–II is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the symptoms of depression, with each item response ranging from “not present” (0) to “severe” (3). The MQoL is a 16-item scale that assesses quality of life in people with life-threatening illness across four domains: physical, psychological, existential, and support. The SAHD is a 20-item true/false measure that assesses patients’ desire for a hastened death in the context of a life-limiting medical illness. The MSAS assesses the presence, frequency, severity, and distress of 32 common symptoms (e.g., lack of energy, difficulty swallowing, hair loss) during the past week. Additionally, the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale (Karnofsky & Burchenal, 1949), an index of functional status with descriptors at 10-point intervals ranging from 0 (“dead”) to 100 (“normal, no complaints; no evidence of disease”), was rated by study research assistants. Each of the study measures has been widely used and well validated in terminally ill samples.

Statistical Analyses

The reliability of the DUFSS was evaluated using analyses grounded in classical test theory (CTT) and item-response theory (IRT). For example, the scale's internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach's coefficient alpha (a) and examination of the corrected item–total correlations, and the factor structure of the DUFSS was analyzed with a principal components factor analysis. In addition, item trace curves (ICCs) and item information curves (IICs) were analyzed to identify better/worse items in terms of their relationship with the underlying latent construct (social support). Only participants who provided complete responses to the DUFSS (n = 940) were included in the IRT analyses due to the sample size requirements (<1000 cases) of IRTpro (Student Edition), the program used for analysis. The initial IRT analyses utilized a graded response model (Samejima, 1969) with five response options (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) per item. These data were used to identify a shorter subset of DUFSS items that might retain comparable reliability and validity. Additionally, highly skewed and/or kurtotic items (>2.0) were considered for elimination, as well as items with very high item–total correlations (>0.75; Ferketich, 1991) or low factor loadings on a single-factor model (<0.40; Clark & Watson, 1995).

Using the validation sample, CTT analyses were again employed to assess the reliability and validity of the abbreviated DUFSS. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to determine construct validity of both the 14- and 5-item versions of the DUFSS. To assess convergent validity, correlations were calculated between the DUFSS short form (DUFSS-5) and the BDI, MQoL, and SAHD. In order to explore the main-effect and buffering models of social support, a series of multiple regression analyses were computed (using z-transformed variables) that included DUFSS-5, KPS, and MSAS scores as independent variables as well as the interaction terms (DUFSS × KPS, DUFSS × MSAS); BDI, MQoL, and SAHD scores were entered as dependent variables.

RESULTS

Analysis of the Original 14-Item Scale

The mean total DUFSS score for the sample was 42.85 (SD = 13.89, range = 0–56). Mean scores for each of the 14 items and their standard deviations, skew, and kurtosis are presented in Table 1. All items were negatively skewed, but only one (item 5, “people who care what happens to me”) had skew and kurtosis values exceeding 2.0. Internal consistency for the 14-item scale was strong (Cronbach's α = 0.94), and corrected item–total correlations ranged from 0.64 to 0.76. Only one (item 9, “chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal and family problems”) exceeded the a priori cutoff of an item–total correlation greater than 0.75 for identifying overly redundant items. None of the items resulted in an increased coefficient α by their removal.

Table 1.

DUFSS total and item means, skew, kurtosis, and standard deviations

| DUFSS Item | Mean (SD) | Skew | Kurtosis | Item Total r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Visits from friends and family . . . | 2.81 (1.42) | –0.87 | –0.63 | 0.69 |

| 2. Help . . . | 3.12 (1.20) | –1.28 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| 3. Help with money in emergency . . . | 2.93 (1.45) | –1.06 | –0.37 | 0.69 |

| 4. Praise for a good job . . . | 2.92 (1.37) | –1.06 | –0.17 | 0.64 |

| 5. People who care what happens to me . . . | 3.50 (0.99) | –2.15 | 3.98 | 0.68 |

| 6. Love and affection . . . | 3.33 (1.18) | –1.76 | 1.93 | 0.75 |

| 7. Telephone calls from people I know . . . | 3.15 (1.30) | –1.37 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| 8. Chances to talk to someone about problems at work or with my housework | 2.97 (1.39) | –1.10 | –0.17 | 0.75 |

| 9. Chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal and family problems . . . | 3.06 (1.34) | –1.23 | 0.17 | 0.76 |

| 10. Chances to talk about money matters . . . | 2.95 (1.42) | –1.07 | –0.30 | 0.74 |

| 11. Invitations to go out and do things with other people . . . | 2.82 (1.47) | –0.89 | –0.69 | 0.69 |

| 12. Useful advice about important things in life . . . | 3.01 (1.29) | –1.12 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

| 13. Help when I need transportation . . . | 3.11 (1.34) | –1.30 | 0.30 | |

| 14. Help when I am sick in bed . . . | 3.25 (1.20) | –1.55 | 1.28 | 0.66 |

Although prior research with the DUFSS has identified a two-factor structure (Broadhead et al., 1988), principal components analysis of our sample supported a one-factor model. The first factor (eigenvalue = 7.99) accounted for 57% of the variance in DUFSS scores; the addition of a second factor accounted for an additional 6.55% of the variance (eigenvalue = 0.92). Factor loadings for the one-factor solution were uniformly high, with all items exceeding 0.60.

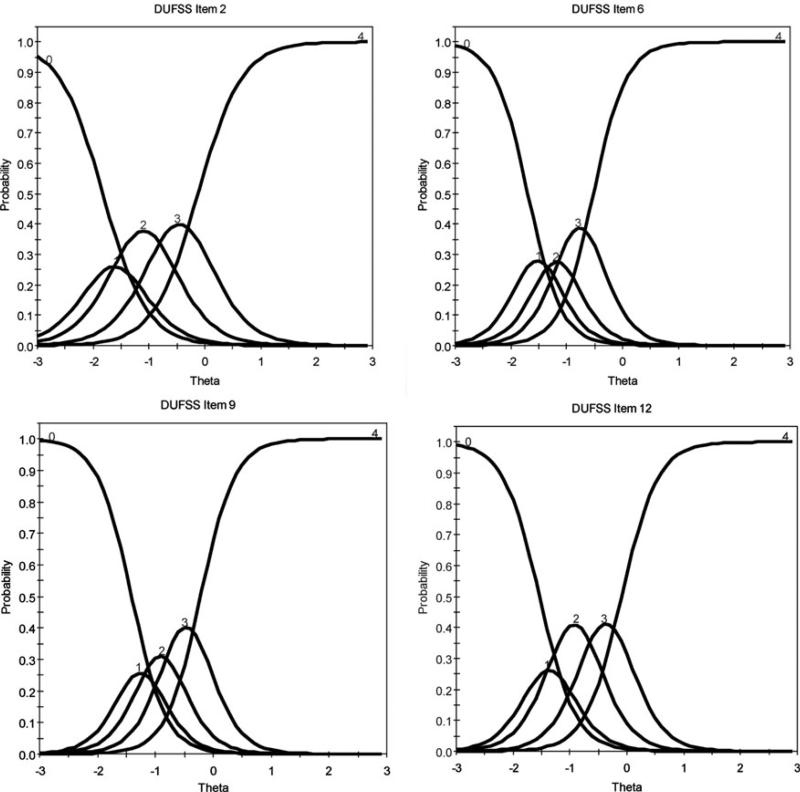

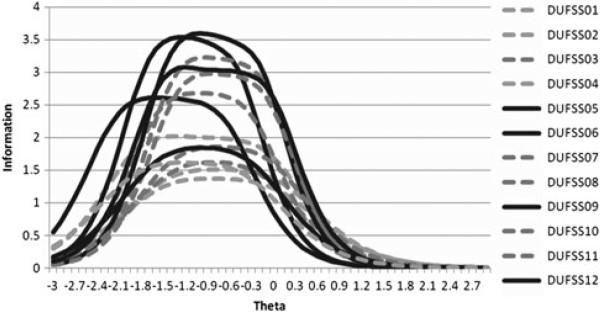

IRT Analyses

Examination of the item parameters revealed that all 14 items had fairly large slopes (range = 1.80–3.62), indicating strong discriminatory power (Table 2). Item characteristic curves (ICCs; see Fig. 1 for several examples) and item information curves (IICs; see Fig. 2) were also calculated and used to select items for use in a short form of the DUFSS. Analysis of the IICs indicated that most items provided a similar level of information (i.e., generated overlapping curves). As there is no established method for selecting items for a short form, efforts were made to select items based on the height, spread, and location of the IICs. This approach maximizes the breadth of information provided by the scale. The ICCs and item level diagnostic statistics (chi square) were also considered in item selection (Table 3). Based on these parameters, items 5, 6, and 9 appeared to provide the most unique information. Item 12 had a high information curve, and visual examination of the ICCs for this item revealed desirable separation between threshold parameters. Item 13 was also deemed beneficial due to both its scale properties and its seemingly strong face validity, providing information about instrumental support (whereas most other items targeted emotional support). The five items selected for the short form are set in boldface type in Table 1.

Table 2.

Graded model item parameter estimates

| Item | a | SE | b 1 | SE | b 2 | SE | b 3 | SE | b 4 | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUFSS01 | 2.08 | 0.17 | –1.45 | 0.10 | –1.06 | 0.08 | –0.53 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| DUFSS02 | 2.52 | 0.20 | –1.75 | 0.12 | –1.38 | 0.09 | –0.77 | 0.07 | –0.14 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS03 | 2.28 | 0.20 | –1.35 | 0.10 | –1.10 | 0.08 | –0.69 | 0.07 | –0.27 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS04 | 1.80 | 0.16 | –1.61 | 0.13 | –1.38 | 0.11 | –0.77 | 0.08 | –0.07 | 0.07 |

| DUFSS05 | 2.87 | 0.27 | –2.02 | 0.14 | –1.79 | 0.12 | –1.23 | 0.08 | –0.73 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS06 | 3.26 | 0.30 | –1.72 | 0.11 | –1.40 | 0.09 | –1.02 | 0.07 | –0.58 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS07 | 2.92 | 0.25 | –1.49 | 0.10 | –1.20 | 0.08 | –0.76 | 0.06 | –0.34 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS08 | 3.09 | 0.26 | –1.40 | 0.09 | –1.04 | 0.07 | –0.61 | 0.06 | –0.16 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS09 | 3.62 | 0.32 | –1.36 | 0.08 | –1.08 | 0.07 | –0.74 | 0.06 | –0.27 | 0.05 |

| DUFSS10 | 3.03 | 0.25 | –1.31 | 0.09 | –1.06 | 0.07 | –0.56 | 0.06 | –0.15 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS11 | 2.11 | 0.18 | –1.43 | 0.11 | –1.07 | 0.09 | –0.59 | 0.07 | –0.13 | 0.07 |

| DUFSS12 | 3.21 | 0.26 | –1.61 | 0.10 | –1.21 | 0.08 | –0.64 | 0.06 | –0.14 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS13 | 2.68 | 0.23 | –1.62 | 0.11 | –1.21 | 0.08 | –0.79 | 0.07 | –0.40 | 0.06 |

| DUFSS14 | 2.20 | 0.19 | –1.89 | 0.13 | –1.55 | 0.11 | –1.02 | 0.08 | –0.42 | 0.06 |

Fig. 1.

Example IRT ICCs from five-response options version of DUFSS.

Fig. 2.

IICs for DUFSS five-response options version of DUFSS. Solid lines represent items selected for inclusion in the short form.

Table 3.

Item level diagnostic statistics

| Item | χ 2 | df | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUFSS01 | 113.57 | 93 | 0.0724 |

| DUFSS02 | 121.39 | 85 | 0.0059 |

| DUFSS03 | 124.28 | 94 | 0.0199 |

| DUFSS04 | 116.41 | 91 | 0.0374 |

| DUFSS05 | 73.65 | 63 | 0.1685 |

| DUFSS06 | 74.31 | 65 | 0.2007 |

| DUFSS07 | 97.76 | 82 | 0.1128 |

| DUFSS08 | 114.31 | 88 | 0.0312 |

| DUFSS09 | 87.05 | 77 | 0.2029 |

| DUFSS10 | 120.57 | 80 | 0.0023 |

| DUFSS11 | 164.14 | 99 | 0.0001 |

| DUFSS12 | 100.06 | 75 | 0.0282 |

| DUFSS13 | 106.10 | 84 | 0.0519 |

| DUFSS14 | 106.34 | 79 | 0.0218 |

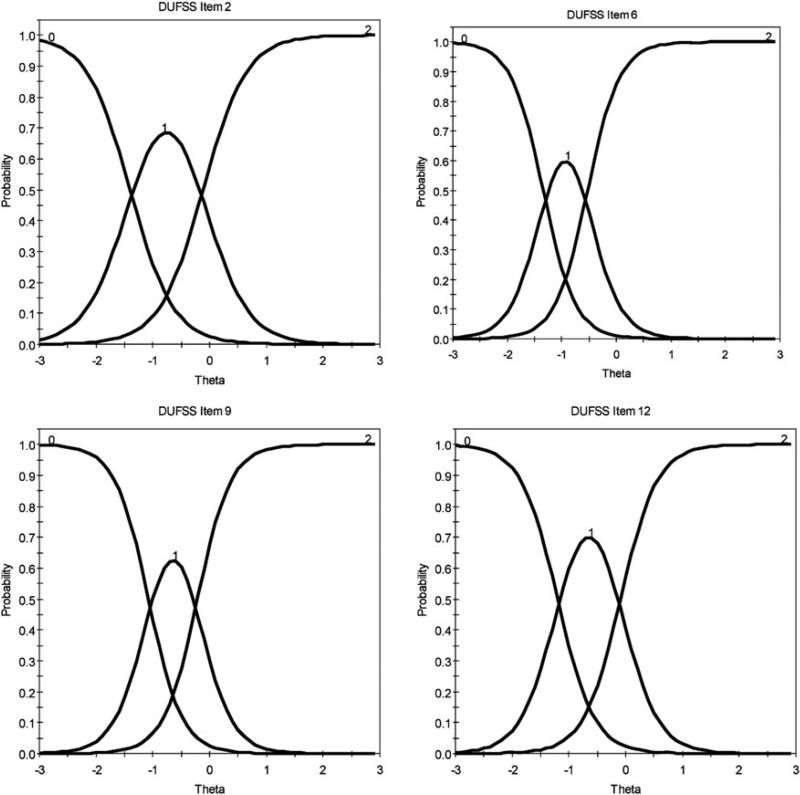

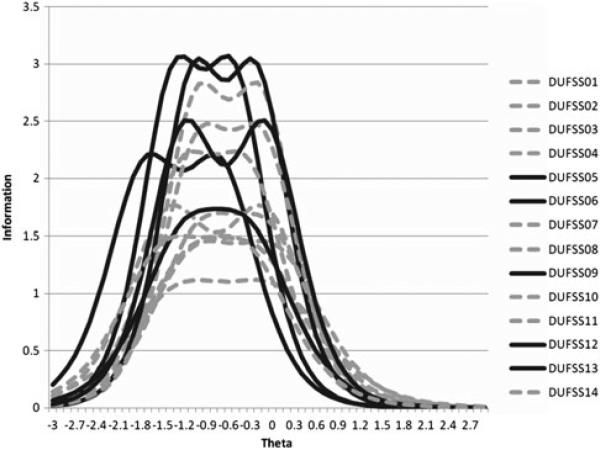

The initial ICCs revealed significant overlap between the trace lines for responses of 0 and 1, and little distinction between the threshold parameters for responses 2 and 3 (see Fig. 1). Participants often endorsed items at the extremes of the scale (0 or 4; see Table 4). The item descriptive statistics and coefficient α were computed for both the original metric and a version of the DUFSS that collapsed item responses into three categories: 0 (responses 0 and 1), 1 (responses 2 and 3), and 2 (response 4). Cronbach's α was 0.94 regardless of whether three or five responses were analyzed, suggesting that little information was lost by collapsing the scale into three response categories. A new graded response IRT model was estimated, and example ICCs are displayed in Figure 3. Examination of the information curves using the three-response version of the DUFSS supported the selection of the same items that had been previously identified using the five-response version of the scale, herein refereed to as the DUFSS-5 (Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Item content and response frequencies for DUFSS (n = 940)

| Scale Value (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item/Content | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Visits from friends and family . . . | 12.6 | 7.4 | 14.1 | 18.5 | 47.3 |

| 2. Help . . . | 6.2 | 5.3 | 14.1 | 21.4 | 53.0 |

| 3. Help with money in an emergency . . . | 13.2 | 5.0 | 11.3 | 14.3 | 54.7 |

| 4. Praise for a good job . . . | 11.9 | 4.7 | 14.0 | 19.8 | 49.6 |

| 5. People who care what happens to me . . . | 3.4 | 3.1 | 7.0 | 13.5 | 73.0 |

| 6. Love and affection . . . | 6.3 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 14.9 | 67.6 |

| 7. Telephone calls from people I know . . . | 8.9 | 5.2 | 10.7 | 14.6 | 60.5 |

| 8. Chances to talk to someone about problems at work or with my housework . . . | 11.4 | 6.0 | 11.9 | 16.7 | 53.9 |

| 9. Chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal and family problems . . . | 9.9 | 6.0 | 10.1 | 17.7 | 56.4 |

| 10. Chances to talk about money matters . . . | 12.7 | 6.0 | 12.4 | 15.6 | 53.3 |

| 11. Invitations to go out and do things with other people . . . | 13.5 | 7.3 | 12.7 | 15.9 | 50.6 |

| 12. Useful advice about important things in life . . . | 8.3 | 5.7 | 15.0 | 19.3 | 51.7 |

| 13. Help when I need transportation . . . | 9.9 | 6.2 | 10.5 | 13.3 | 60.1 |

| 14. Help when I am sick in bed . . . | 6.8 | 4.7 | 10.3 | 15.9 | 62.3 |

Fig. 3.

IRT ICCs from three-response options version of DUFSS.

Fig. 4.

IRT graded response model IICs for three-response options version of DUFSS.

Validation of DUFSS-5

In order to evaluate the DUFSS-5, we applied this abbreviated version to a new sample drawn from a population of ambulatory cancer patients (described above). The 5-item/3-response version of the DUFSS had adequate reliability in this new sample (Cronbach's α = 0.80), and coefficient α did not improve significantly (0.01 or greater) with deletion of any of the five items. The abbreviated scale also demonstrated adequate convergent validity as evidenced by significant correlations in the expected directions, with several measures of psychological distress, including the BDI (r = –0.29, p < 0.001), the MQoL (r = 0.36, p < 0.001), and the SAHD (r = –0.27, p < 0.001). These correlations were slightly smaller than those found for the original 14-item/5-response version of the scale (BDI r = –0.34, p < 0.001; MQoL r = 0.41, p < 0.001; SAHD r = –0.29, p < 0.001).

Both the 14- and 5-item versions of the scale indicated support for the main-effect model of social support, but less support for the buffering model. For both versions of the scale, DUFSS, KPS, and MSAS were each significant predictors of psychological distress scores (BDI, MQoL, and SAHD), but the interaction terms were not significant in most of the models. For example, in the model predicting BDI scores, both the MSAS and DUFSS-5 had significant main effects (B = 0.24, p = 003, and B = –0.26, p = 0.001, respectively), but no significant interaction effect (B = –0.06, p = 0.49). Similarly, in the model incorporating KPS scores, significant main effects were observed for both KPS and DUFSS-5 (B = –0.22, p = 0.006, and B = –0.25, p = 0.002, respectively), but no significant interaction effect (B = –0.02, p = 0.83). However, for the analyses predicting MQoL scores, both the main effects for MSAS and DUFSS-5 were significant (B = –0.34, p < 0.001, and B = 0.30, p < 0.001, respectively), as was the interaction term (B = 0.14, p = 0.05). The interaction was not significant when KPS was entered in place of MSAS score in predicting MQoL scores (B = –0.07, p = 0.37), but both KPS and DUFSS-5 again had significant main effects (B = 0.17, p = 0.03, and B = 0.31, p < 0.001, respectively). Like the models predicting BDI scores, no significant interaction effects were observed for either model predicting SAHD scores, but the DUFSS-5 continued to demonstrate significant main effects in both models.

DISCUSSION

Despite the existence of many social support scales, very few studies have even reported any psychometric properties, let alone analyzed the adequacy of the scales. Hence, researchers have little if any guidance in selecting an optimal scale for measuring social support. Moreover, determining which scale is “optimal” may vary depending on the context in which the study takes place. For example, studies relying on undergraduate college students allow for lengthy measures that tap a wide range of issues using multiple, overlapping items, but studies in healthcare settings may need to prioritize brevity over completeness. The strengths and weaknesses of available social support instruments, and particularly those designed for unique clinical settings (e.g., advanced medical illness), must be explored in order to guide research decision making and interpret published results.

Our research team has utilized the DUFSS in several large-scale research studies of patients with advanced and terminal illness (Breitbart et al., 2000; Kolva et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2002), but to date we have never analyzed the psychometric properties of the measure. These studies have typically demonstrated the expected associations between the DUFSS and relevant outcome variables (e.g., psychological distress). However, the 14-item scale includes several items of questionable relevance for patients who are hospitalized with a severe or life-limiting illness. Moreover, the present study demonstrated a high degree of redundancy in the DUFSS-5 items, with uniformly high item–total correlations that often exceeded levels recommended for scale items (Ferketich, 1991). In addition, item–response patterns raised questions about whether the five-response Likert-type scale provided more information than a simpler three-response format.

We generated a five-item version of the DUFSS-5 that included only three response levels based on CTT and IRT analyses. This revised version of the DUFSS-5 (the DUFSS-5) appeared to provide the greatest levels of information while minimizing the loss in reliability and validity inherent to such brief scales (particularly since some aspects of reliability are contingent on scale length). For example, internal consistency decreased with removal of nine DUFSS items, but the five-item scale still demonstrated adequate reliability in a new sample (α = 0.80). Likewise, correlations between the DUFSS and measures of psychological well-being were only slightly reduced between the 14- and 5-item versions. Thus, the modest decreases observed in this study are encouraging and suggest that the DUFSS-5 possesses sufficiently strong reliability and validity for use in healthcare research.

The abbreviated DUFSS items identified in these analyses overlapped substantially, but not completely, with the eight-item version originally proposed by Broadhead et al. (1988). Four of the DUFSS-5 items were included in their eight-item version. However, one item that was originally eliminated by them, item 13—“help when I need transportation”—was included in the current short form. In addition to strong psychometric properties, this item has obvious face validity in a medically ill population, where patients often need to rely on others for assistance with doctors appointments and other transportation needs. Conversely, several items that were retained in the eight-item DUFSS were not included in the DUFSS-5. Items such as “chances to talk to someone about problems at work or with my housework” and “invitations to go out and do things with other people” appear to be less relevant for a palliative care setting than they may have been in the primary care setting in which the scale was originally validated. Further research may help determine whether different item subsets are preferable in other healthcare settings.

The development of brief rating scales is particularly critical for palliative care research, where issues of patient burden and deteriorating physical health often compromise data collection. In addition, many research settings are constrained in terms of time and resources. Lengthy research protocols can be overly burdensome for this vulnerable population, and researchers are often forced to make tradeoffs between brief assessments for a wide range of constructs versus a more thorough assessment of a narrower range of topics (Pessin et al., 2007). The development of brief measures that retain adequate reliability and validity provides an option for researchers who may seek to address a broad range of issues yet are limited by external constraints.

The current findings also underscore the need to use rigorous methods for scale development (e.g., IRT) rather than simply relying on traditional CTT analysis. In the present exploration, CTT revealed very little distinction between the scale items but IRT generated greater sensitivity in discriminating among scale items. The use of IRT has become increasingly popular in healthcare settings (Cella et al., 2007) for the purposes of scale development and evaluation, but it is not yet the norm. Although IRT analyses generated more information about the scale items, there are no established procedures for selecting items to retain in an abbreviated scale, nor any guidance as to how to resolve discrepancies (when they occur) between the CTT and IRT results. For example, item 5 (“people who care what happens to me”) appeared to be highly redundant based on CTT analyses, but IRT analyses identified this item as one of the most useful (i.e., highly discriminating), and thus was retained in the five-item version. Conversely, item 13 (“help when I need transportation”) was no stronger than some of the other items, but had relatively strong face validity and was therefore retained. In general, we attempted to maximize the information provided by the abbreviated scale by selecting items that were highly discriminating and reflected the greatest range of item difficulty while simultaneously maintaining a high level of face validity. However, it certainly is possible that alternative combinations of items could have provided comparable levels of reliability and validity. As psychometric methods for better understanding scale properties continue to improve, concrete guidelines for item selection may help refine the process of scale development.

Finally, the present investigation found support for the main-effect model of social support, but less support for the buffering model. Although measures of functional status (MSAS and KPS) and social support (DUFSS) independently predicted psychological distress variables in a series of multiple regression models, only one of the six models tested demonstrated a siginificat buffering effect for the DUFSS-5, moderating the relationship between physical symptom distress (MSAS) and overall quality of life. These findings are consistent with past research in which the main-effect model of social support has been consistenly upheld while evidence for the buffering effect has been mixed (Thoits, 1985). The limited evidence for the buffering effect observed in our study may be due to the high level of stress experienced by this sample, as all participants were diagnosed with an advanced, life-threatening illness and many were approaching death.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations must be considered in interpreting our study findings. Because most study participants were hospitalized, one DUFSS item (“help around the house”) was changed to simply “help . . .” since the item would be irrelevant for many individuals. Although it is unlikely that this change to a single item significantly impacted the usefulness of the scale (or item) in our sample, this assumption cannot be tested with the available data. Additionally, the DUFSS was orally administered to some participants, when fatigue or visual impairment precluded reading the study measures. It is unclear whether this may have impacted item endorsement patterns, but could not be evaluated since the method of administration was not recorded.

The generalizability of the utility of the DUFSS within advanced illness and palliative care samples is also limited in that validity was only determined through correlations with measures of depression, desire for hastened death, and quality of life, along with tests of the main-effect and buffering models. More extensive social support measures, collateral information about social support (i.e., caregiver report), and/or qualitative patient interviews would have each provided more data with which to determine the convergent validity of the DUFSS. However, because social support was not the central focus of these research studies, such data were not available. Finally, the generalizability of these study results is further limited because many participants were recruited from state-of-the-art facilities that tend to provide an unusually high level of patient care. The DUFSS may have shown more variability in patients drawn from more diverse healthcare settings.

Despite these limitations, both the DUFSS-5 and the abbreviated version, the DUFSS-5, appear to have adequate reliability and validity in this setting. Moreover, the DUFFS-5 represents a potentially important option for healthcare researchers, particularly for those working in palliative care settings where issues of patient burden are paramount. Such analyses are critical in advancing the development and refinement of psychosocial measures but have often been neglected. Future studies of social support should address the psychometric properties of the scales they utilize in order to identify better (and worse) approaches to measuring social support. Moreover, study designs that take a phenomenological, ground–up perspective may inform the development of new social support scales that better address the facets of social support considered important in distinct clinical populations.

REFERENCES

- Ahumada L, Bailón E, Luna J, et al. Validation of a functional social support scale for use in the family doctor's office. Atención Primaria. 1991;8:688–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth J, Schneider S, Von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:229–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, et al. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories 1A and II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;19:21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1304–1309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, DeGruy FV, et al. The Duke–UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical Care. 1988;26:709–723. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, DeGruy FV, et al. Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Medical Care. 1989;27:221–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap Cooperative Group during its first two years. Medical Care. 2007;45(5):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:309–319. doi: 10.1037/pas0000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, McKay G. Social support, stress, and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In: Baum A, et al., editors. Handbook of psychology and health. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. pp. 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme SL. Issues in the study and application of social support. In Social support and health. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1985. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, et al. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliative Medicine. 1995;9:207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004;23:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom CS, Shin DW, Kim SY, et al. Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients: Results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;22(6):1283–1290. doi: 10.1002/pon.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferketich S. Focus on psychometrics: Aspects of item analysis. Research in Nursing & Health. 1991;14(2):165–168. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: A practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A, Fernández C, García G, et al. Quality of life parameters in terminal oncological patients in a home care unit. Psychology in Spain. 2002;6:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hann DM, Oxman TE, Ahles TA, et al. Social support adequacy and depression in older patients with metastatic cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1995;4:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Mac-Leod CM, editor. In Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Columbia University Press; New York: 1949. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke C, Kubzansky L, Schernhammer ES, et al. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke C, Michael Y, Tindle H, et al. Social networks, social support and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;133:375–385. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1962-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:213–200. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olden M, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Measuring depression at the end of life: Is the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale a valid instrument? Assessment. 2009;16(1):43–54. doi: 10.1177/1073191108320415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren ML, Carella M, Helma T. Diabetes support group: Study results and implications. Employee Assistance Quarterly. 1996;11:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomér K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1993;55(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessin H, Gallieta M, Nelson CJ, et al. Burden and benefit of psychosocial research at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;11:627–632. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Duberstein P. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2010;75:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy RK, Thaler H,T, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: An instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT. Social interaction and well-being. In Personal relationship. In: Duck S, editor. Repairing personal relationships. Vol. 5. Academic Press; London: 1984. pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ringdal GI, Ringdal K, Jordhøy MS, et al. Does social support from family and friends work as a buffer against reactions to stressful life events such as terminal cancer? Palliative & Supportive Care. 2007;5:61–69. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, et al. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/ AIDS. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:94–100. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Gibson C, et al. Desire for hastened death among patients with advanced AIDS. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:504–512. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.6.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Lewis C, et al. Assessing hopelessness in terminally ill cancer patients: Development of the Hopelessness Assessment in Illness Questionnaire (HAI). Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:325–336. doi: 10.1037/a0021767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saameño JA, Sánchez A, Castillo JD, et al. Validity and reliability of the Duke–UNC-11 questionnaire of functional social support. Atención Primaria. 1996;18:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Psychometric Monograph No. 17. Psychometric Society; Richmond, VA: 1969. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Available at http://www.psychometrika.org/journal/online/MN17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Social support processes and psychological well-being: Theoretical possibilities. In: Sarason IG, Sarason B, editors. Social support: Theory, research and applications. Martinus Nijhoff; The Hague: 1985. pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. What a lifespan approach might tell us about why distinct measures of social support have differential links to physical health. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2009;26:53–62. doi: 10.1177/0265407509105521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangelisti AL. Challenges in conceptualizing social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2009;26:39–51. [Google Scholar]