Abstract

Background

Studies indicate adherence to biologics among patients with psoriasis is low, yet little is known about their use in the Medicare population.

Objective

We sought to investigate real-world utilization patterns in a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis initiating infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, or ustekinumab.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective claims analysis using 2009 through 2012 100% Medicare Chronic Condition Data Warehouse Part A, B, and D files, with 12-month follow-up after index prescription. Descriptive and multivariate analyses were used to examine rates of and factors associated with biologic adherence, discontinuation, switching, and restarting.

Results

We examined 2707 patients initiating adalimumab (40.0%), etanercept (37.9%), infliximab (11.7%), and ustekinumab (10.3%); during 12-month follow-up, 38% were adherent and 46% discontinued treatment, with 8% switching to another biologic and 9% later restarting biologic treatment. Being female and being ineligible for low-income subsidies were associated with increased odds of decreased adherence. Outcomes varied by index biologic.

Limitations

Patient-reported reasons for nonadherence or gaps in treatment are unavailable in claims data.

Conclusion

Medicare patients initiating biologics for psoriasis had low adherence and high discontinuation rates. Further investigation into reasons for inconsistent utilization, including exploration of patient and provider decision-making and barriers to more consistent treatment, is needed.

Keywords: adalimumab, adherence, biologic, discontinuation, etanercept, infliximab, Medicare, psoriasis, specialty drug, ustekinumab

Psoriasis is a chronic, multisystem, inflammatory disease that affects as many as 7.5 million people in the United States.1 It is associated with significant physical,2 psychosocial,3 and economic4 burden. Biologics represent an important treatment option for moderate to severe disease, which affects approximately 20% of all patients with psoriasis.5 Five biologics are currently approved in the US to treat moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, yet numerous studies indicate that adherence to biologics in the real-world setting is low.6–9

Existing research on biologic treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis in the US has largely focused on privately insured populations.6–9 Little is known about treatment patterns among US elderly and disabled individuals, the majority of whom are covered by Medicare, a nationwide health insurance program administered by the US federal government.10 Lack of data on the treatment of psoriasis in the elderly has been identified as a major research gap,11 especially because they are often underrepresented in clinical trials and may have unique treatment concerns.10,12 To address this gap, we examined national claims data for Medicare patients with psoriasis who were initiating biologics to investigate adherence, discontinuation, switching, and restarting of biologic treatment.

METHODS

Data

We performed a retrospective claims analysis using the 2009 through 2012 100% Medicare Chronic Condition Data Warehouse files, including the Medicare inpatient (Part A), outpatient (Part B), and prescription drug (Part D) data files linked with beneficiary summary files and Part D prescription drug plan characteristics files.

Sample

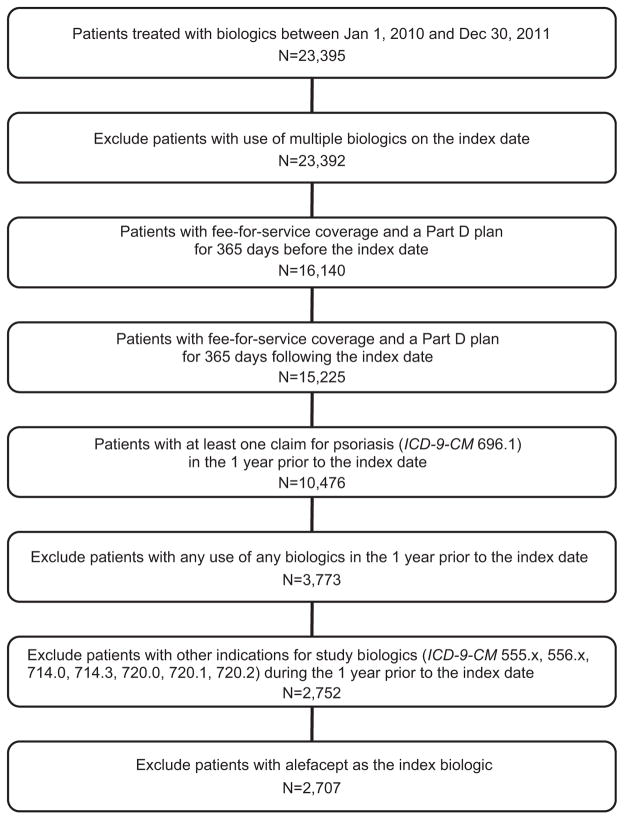

Patients were included if they: (1) had a claim for a biologic approved for treatment of plaque psoriasis (ie, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, or ustekinumab) between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2011 (representing the index date); (2) had continuous enrollment in fee-for-service Medicare and a stand-alone Part D prescription plan in the 12 months before and after the index date; (3) had no claims for a biologic approved for psoriasis in the 12 months before the index date, thus identifying a new biologic treatment episode; and (4) had at least 1 claim for psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 696.1) in the 12 months before their index date (Appendix Figure 1; available at http://www.jaad.org). Patients were excluded if they: (1) had other indications for which the study biologics are approved (ie, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease) in the pre-index period; (2) were using multiple biologics for psoriasis on the index date; or (3) were using alefacept, which was withdrawn from the market in November 2012, as the index biologic. Secukinumab was not approved during the study period and thus not included. Because patients were required to have a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis, individuals with psoriatic arthritis in the absence of skin disease were not included. Patients were followed up for 12 months after their index date.

Appendix Fig 1.

Sample selection diagram. ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Although Medicare is primarily a program for elderly and disabled adults, children are eligible beneficiaries under some restricted circumstances. We did not impose an age restriction on our sample, but application of other study criteria resulted in a sample with a minimum age of 21 years.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included adherence to, discontinuation of, switching from, and restarting of the index biologic. Adherence was captured using the proportion of days covered (PDC), measured as the number of days covered with the index biologic divided by a fixed time interval (ie, 365 days) from the date of index biologic therapy initiation.13 For example, a patient with biologic coverage available for 292 days during the 365 day post-index date period would have a PDC of 292/365 = 0.80.14 Patients with PDC greater than or equal to 0.80 were classified as adherent.15,16

Number of days covered with each biologic was captured based on its mode of administration. Etanercept and adalimumab, self-administered biologics dispensed via the pharmacy, were identified from the Part D prescription records using National Drug Codes (NDC codes). Prescription fill date and days’ supply information were used to calculate the number of days covered by each biologic fill. Infliximab, which requires infusion under supervision of a medical professional, was identified from Part B medical claims using the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS codes). Because Part B claims do not include days’ supply information, we assigned days’ supply after each administration using infliximab’s recommended dosage regimen and then used the assigned days’ supply and administration date to calculate covered days (Appendix Table I; available at http://www.jaad.org). Ustekinumab, administered by subcutaneous injection and approved only for administration by a medical professional during our study period (under Part B), was nonetheless found in both Part D prescription records and Part B medical claims among the study sample. Thus, we calculated ustekinumab-covered days using the prescription fill or administration dates and assigned days’ supply.

Appendix Table I.

Identification of biologic agents and assignment of days’ supply

| Biologic agent | Biologic identified from Part B or D claims | Recommended dosage schedule | Days’ supply as reported or assigned | Rules for assigning days’ supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enbrel (etanercept) | Part D | 50 mg 2×/wk for 12 wk, then 50 mg 1×/wk | As reported | NA |

| Humira (adalimumab) | Part D | 80 mg once on wk 0, then 40 mg once every 2 wk starting on wk 1 | As reported | NA |

| Remicade (infliximab) | Part B | 5 mg/kg on wk 0, 2, and 6, then every 8 wk | Assigned | First administration: 14 d; second administration: 28 d; ≥third administration: 56 d |

| Stelara (ustekinumab) | Part B and D* | 45 mg (≤100 kg) or 90 mg (>100 kg) once on wk 0 and wk 4, then every 12 wk | Assigned† | First administration or fill: 28 d; ≥second administration or fill: 84 d |

Manufacturers: Enbrel, Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA; Humira, AbbVie Inc, North Chicago, IL; Remicade, Janssen Biotech, Inc, Horsham, PA; Stelara, Janssen Biotech, Inc, Horsham, PA.

Ustekinumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and was only approved for administration by a medical professional during our study period (ie, covered under Part B). Ustekinumab use under Part D may reflect some clinicians requiring patients to pick up prescriptions from the pharmacy and bring them to office visits for administration.

Our assessment of the days’ supply field for Part D ustekinumab claims revealed a large proportion of the ≥second fills being consistently coded as 28-d or 30-d supply despite their fill dates being approximately 12 wk (ie, 84 d) apart. Hence, we assigned days’ supply to both Part D and B ustekinumab claims based on the dosage schedule.

Discontinuation, generally operationalized as a continuous gap in availability of treatment for a prespecified period of time,6,8 was our primary outcome and captured via a dichotomous measure indicating the presence of a period of 90 consecutive days or more without the index biologic during the 12-month follow-up period.14 That is, if another prescription fill (or administration) for the index biologic did not occur at least 90 consecutive days after the final day covered by the previous days’ supply (or assigned days’ supply) of a fill (or administration) of the biologic, then this was coded as discontinuation.

Finally, we measured whether patients who discontinued their index biologic switched to another biologic, defined as the first occurrence of a prescription fill for or administration of a different (substitute) biologic (Part B or Part D) within 90 days after the last day of supply of the index biologic; or restarted biologic treatment, defined as a prescription fill for or administration of the index biologic or another biologic after the continuous gap of 90 days or more but within 1 year after the index date. Patients who had neither switched nor restarted biologic treatment before the end of the follow-up period were categorized as other discontinuers.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive outcomes were calculated overall and by type of index biologic. Logistic regressions were used to examine adherence and discontinuation. Multinomial logistic regressions were used to examine factors associated with being switchers, restarters, and other discontinuers compared with continuous biologic users. The regressions included a series of covariates including patient age, sex, race, census region, Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) status, county-level per capita income, county-level availability of dermatologists (as a general proxy for treatment accessibility), and Part D plan type. We also controlled for relevant comorbidities,2,17–20 number of other nonpsoriasis medications, and the prescription drug hierarchical condition category score,21 which has been used to adjust for potential selection biases in drug use studies among Medicare patients.22–25 In addition, we included indicators for index date year to capture any temporal trends and for each index biologic; ustekinumab, the newest biologic on the market at the time of the study, was used as the reference.

Analyses were repeated in 3 subgroups: (1) disabled (ie, age <65 years), (2) elderly (ie, age ≥65 years), and (3) those without medical claims for psoriatic arthritis. All analyses were conducted in SAS, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Our sample included 2707 patients, of which 1084 (40.0%) initiated adalimumab, 1025 (37.9%) initiated etanercept, 318 (11.7%) initiated infliximab, and 280 (10.3%) initiated ustekinumab. Table I presents sample characteristics by index biologic cohort. Nearly half of the sample (48.9%) was younger than 65 years (ie, eligible for Medicare based on disability), and 43.9% were male. Age and sex were generally similar across index drug cohorts, although a smaller percentage of patients receiving infliximab were younger than 65 years. Fewer patients receiving infliximab were eligible for full LIS (27.8%, vs more than half of all other biologic groups). Cardiometabolic disorders were the most prevalent comorbidities. Overall prevalence of psoriatic arthritis was 28.9%; however, it was substantially higher among patients on infliximab (70.8%) and lowest among patients on ustekinumab (15.7%), which had not yet been approved for psoriatic arthritis during our study period. As indicators of overall comorbidity, the average number of nonpsoriasis medications among the overall sample was 4.89 (SD 3.63), and the mean prescription drug hierarchical condition category score was 1.13 (SD 0.65).

Table I.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | All, N = 2707 | Adalimumab, n = 1084 | Etanercept, n = 1025 | Infliximab, n = 318 | Ustekinumab, n = 280 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.7 (14.5) | 59.4 (14.4) | 60.3 (14.9) | 65.5 (12.0) | 61.6 (15.1) |

| Age category, y | |||||

| <65 | 48.9% | 54.7% | 50.6% | 28.0% | 44.3% |

| 65–69 | 19.5% | 16.9% | 19.1% | 31.1% | 17.5% |

| 70–74 | 16.3% | 14.7% | 14.3% | 24.5% | 20.0% |

| 75–79 | 8.0% | 7.7% | 7.9% | 8.2% | 9.6% |

| ≥80 | 7.3% | 6.0% | 8.1% | 8.2% | 8.6% |

| Sex, male | 43.9% | 43.7% | 42.0% | 48.7% | 46.1% |

| Race | |||||

| White | 84.6% | 83.9% | 84.0% | 91.2% | 82.8% |

| Black | 6.5% | 7.2% | 6.7% | 3.5% | 6.1% |

| Hispanic | 3.5% | 2.6% | 4.1% | 3.1% | 5.0% |

| Other/unknown | 5.4% | 6.3% | 5.2% | 2.2% | 6.1% |

| Census region | |||||

| Northeast | 15.6% | 14.8% | 15.6% | 14.4% | 19.9% |

| Midwest | 22.4% | 22.5% | 23.8% | 23.3% | 16.1% |

| South | 43.2% | 43.0% | 41.3% | 48.1% | 45.4% |

| West | 18.8% | 19.7% | 19.3% | 14.2% | 18.6% |

| County-level characteristics | |||||

| Income, per capita, $10,000s, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.4) |

| Dermatologists/10,000 residents, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.4) |

| Part D low-income subsidy status | |||||

| Full | 60.6% | 69.5% | 62.5% | 27.8% | 55.7% |

| Partial | 1.6% | 1.4% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 1.8% |

| None | 36.6% | 28.2% | 33.9% | 70.4% | 41.1% |

| Mixed (switched status) | 1.2% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 0.9% | 1.4% |

| Drug benefit type | |||||

| Basic alternative | 30.5% | 25.3% | 32.7% | 40.3% | 31.8% |

| Defined standard benefit | 9.7% | 9.9% | 10.8% | 6.9% | 8.2% |

| Actuarially equivalent standard | 38.6% | 45.9% | 38.0% | 18.9% | 35.4% |

| Unknown | 3.8% | 3.8% | 3.7% | 3.8% | 3.9% |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 4.1% | 1.4% |

| Congestive heart failure | 8.1% | 7.0% | 7.1% | 8.5% | 15.4% |

| Diabetes | 35.1% | 35.8% | 33.9% | 32.7% | 39.6% |

| Dyslipidemia | 53.1% | 51.3% | 52.4% | 60.4% | 54.6% |

| Hypertension | 61.4% | 59.8% | 60.0% | 67.0% | 66.1% |

| Obesity | 11.9% | 12.5% | 11.0% | 11.9% | 12.9% |

| Atherosclerotic conditions | 16.2% | 14.9% | 16.3% | 18.6% | 18.2% |

| Liver disease | 7.3% | 6.9% | 7.8% | 7.2% | 6.8% |

| Dementia | 1.0% | 0.6% | 1.3% | 1.9% | 1.1% |

| Depression | 19.8% | 21.6% | 19.6% | 16.7% | 17.5% |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 28.9% | 25.5% | 23.2% | 70.8% | 15.7% |

| Renal disease | 8.2% | 7.8% | 8.5% | 6.0% | 11.4% |

| Immunosuppressive conditions | 5.5% | 5.3% | 5.8% | 4.7% | 6.8% |

| No. of 30-d supply equivalent prescriptions for nonpsoriasis medications, mean (SD) | 4.89 (3.63) | 4.95 (3.78) | 4.79 (3.50) | 4.72 (3.36) | 5.21 (3.75) |

| RxHCC score, mean (SD) | 1.13 (0.65) | 1.15 (0.66) | 1.13 (0.67) | 1.09 (0.58) | 1.12 (0.59) |

| Index year | |||||

| 2010 | 46.4% | 47.6% | 51.3% | 42.1% | 46.4% |

| 2011 | 53.6% | 52.4% | 48.7% | 57.9% | 53.6% |

Rheumatologic disease category excludes rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerotic conditions category includes cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Immunosuppressive conditions include HIV/AIDS, cancer, and metastatic solid tumor.

RxHCC, Prescription drug hierarchical condition category.

Descriptive outcomes, both overall and by type of index biologic, are summarized in Table II. Overall, 37.7% of patients were adherent, average PDC was 0.61 (SD 0.31), and 45.5% of all patients discontinued their biologic during the 12-month follow-up period. In all, 8% of the sample switched to another biologic for psoriasis, and 9.2% restarted treatment after a 90-day gap. Restarting the initial biologic was more common than restarting with a different biologic.

Table II.

Adherence, discontinuation, switch, and restart outcomes*

| Outcome | All | Adalimumab | Etanercept | Infliximab | Ustekinumab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||

| N | 2707 | 1084 | 1025 | 318 | 280 |

| PDC, mean (SD) | 0.61 (0.31) | 0.63 (0.31) | 0.56 (0.31) | 0.66 (0.32) | 0.70 (0.28) |

| Adherent (PDC ≥0.80) | 37.7% | 40.7% | 29.4% | 49.4% | 43.2% |

| Discontinued | 45.5% | 43.4% | 51.7% | 42.5% | 35.0% |

| Switched | 8.0% | 9.0% | 9.5% | 5.0% | 1.8% |

| Restarted | 9.2% | 6.6% | 9.9% | 10.4% | 15.0% |

| With index biologic | 7.6% | 5.1% | 8.4% | 6.9% | 15.0% |

| With different biologic | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 3.5% | 0.0% |

| Other discontinuer | 28.4% | 27.8% | 32.4% | 27.0% | 18.2% |

| Age <65 y | |||||

| N | 1325 | 593 | 519 | 89 | 124 |

| PDC, mean (SD) | 0.62 (0.30) | 0.65 (0.30) | 0.57 (0.34) | 0.59 (0.34) | 0.73 (0.27) |

| Adherent (PDC ≥0.80) | 37.7% | 43.3% | 29.1% | 40.4% | 45.2% |

| Discontinued | 44.1% | 40.6% | 50.3% | 49.4% | 30.6% |

| Switched | 9.5% | 9.1% | 11.8% | 7.9% | 3.2% |

| Restarted | 9.8% | 7.3% | 10.4% | 14.6% | 15.3% |

| With index biologic | 7.8% | 5.1% | 8.7% | 10.1% | 15.3% |

| With different biologic | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.7% | 4.5% | 0.0% |

| Other discontinuer | 24.8% | 24.3% | 28.1% | 27.0% | 12.1% |

| Age ≥65 y | |||||

| N | 1382 | 491 | 506 | 229 | 156 |

| PDC, mean (SD) | 0.61 (0.32) | 0.60 (0.32) | 0.55 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.31) | 0.68 (0.28) |

| Adherent (PDC ≥0.80) | 37.6% | 37.5% | 29.6% | 52.8% | 41.7% |

| Discontinued | 47.0% | 46.6% | 53.2% | 39.7% | 38.5% |

| Switched | 6.5% | 9.0% | 7.1% | 3.9% | 0.6% |

| Restarted | 8.6% | 5.7% | 9.3% | 8.8% | 14.7% |

| With index biologic | 7.4% | 5.1% | 8.1% | 5.7% | 14.7% |

| With different biologic | 1.2% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 3.1% | 0.0% |

| Other discontinuer | 31.9% | 32.0% | 36.8% | 27.1% | 23.1% |

| No medical claims for psoriatic arthritis | |||||

| N | 1720 | 719 | 715 | 72 | 214 |

| PDC, mean (SD) | 0.60 (0.31) | 0.63 (0.31) | 0.55 (0.30) | 0.61 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.29) |

| Adherent (PDC ≥0.80) | 35.6% | 42.0% | 26.2% | 41.7% | 43.9% |

| Discontinued | 46.6% | 42.3% | 54.0% | 47.2% | 36.0% |

| Switched | 8.4% | 9.6% | 9.5% | 4.2% | 2.3% |

| Restarted | 9.2% | 6.4% | 9.9% | 13.9% | 14.0% |

| With index biologic | 7.7% | 4.7% | 8.5% | 9.7% | 14.0% |

| With different biologic | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.4% | 4.2% | 0.0% |

| Other discontinuer | 29.0% | 26.3% | 34.5% | 29.2% | 19.6% |

PDC, Proportion of days covered.

Discontinuation defined as continuous gap of 90 d. Switch indicates beginning treatment with a new biologic within 90 d of discontinuing the index biologic. Restart indicates resuming treatment with the index biologic or a new biologic after 90 d of discontinuing the index biologic. Other indicates no resumption of treatment before the end of the follow-up period.

Mean PDC varied and was lowest for etanercept (mean PDC 0.56, SD 0.31) and highest for ustekinumab (mean PDC 0.70, SD 0.28). The percentage of adherent patients also varied, from 29.4% for etanercept to 49.4% for infliximab. Rates of discontinuation ranged from 35.0% for ustekinumab to 51.7% for etanercept. Discontinuing the index biologic and switching to another occurred in a small proportion of patients, from 1.8% of ustekinumab users to 9.5% of etanercept users. Discontinuation of the index biologic and subsequent restart of a biologic was less common among adalimumab users (6.6%) and more common among ustekinumab users (15%). Subgroup analyses among elderly, disabled, and those without a concomitant diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis were generally consistent with the main analysis, with the exception of lower adherence and higher discontinuation rates for infliximab in the disabled and psoriasis only subgroups.

Factors associated with lower odds of being adherent included age younger than 65 years or older than 75 years (compared with beneficiaries aged 65–74 years); being female; and being ineligible for full LIS (Table III). With the exception of atherosclerotic conditions, comorbidities and other markers of pharmacologic complexity were not significantly associated with adherence. Compared with patients on index ustekinumab, use of index etanercept was associated with lower odds of adherence.

Table III.

Odds of adherence (proportion of days covered ≥0.80) among Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age category, y | |||

| <65 | 0.74 | 0.57–0.95 | .019 |

| 65–69 | Ref | ||

| 70–74 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.05 | .110 |

| 75–79 | 0.66 | 0.47–0.94 | .020 |

| ≥80 | 0.67 | 0.47–0.97 | .032 |

| Sex, male | 1.28 | 1.08–1.51 | .004 |

| Race | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 0.88 | 0.62–1.24 | .456 |

| Hispanic | 1.21 | 0.78–1.88 | .395 |

| Other/unknown | 0.96 | 0.66–1.39 | .837 |

| Census region | |||

| Northeast | Ref | ||

| Midwest | 1.26 | 0.95–1.66 | .113 |

| South | 1.11 | 0.85–1.45 | .435 |

| West | 1.26 | 0.94–1.67 | .121 |

| County-level characteristics | |||

| Income, per capita, $10,000s | 1.05 | 0.94–1.17 | .393 |

| Dermatologists/10,000 residents | 0.88 | 0.62–1.26 | .490 |

| Low-income subsidy status | |||

| Full | Ref | ||

| Partial | 0.86 | 0.45–1.65 | .647 |

| None | 0.67 | 0.51–0.88 | .004 |

| Mixed (switched status) | 0.34 | 0.14–0.83 | .018 |

| Drug benefit type | |||

| Enhanced alternative | Ref | ||

| Basic alternative | 1.19 | 0.92–1.52 | .183 |

| Defined standard benefit | 1.34 | 0.93–1.92 | .118 |

| Actuarially equivalent standard | 0.94 | 0.71–1.25 | .669 |

| Unknown | 1.04 | 0.65–1.66 | .872 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.27 | 0.70–2.28 | .434 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.06 | 0.77–1.45 | .738 |

| Diabetes | 0.88 | 0.73–1.07 | .215 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.14 | 0.95–1.36 | .164 |

| Hypertension | 1.03 | 0.85–1.25 | .733 |

| Obesity | 1.03 | 0.80–1.33 | .829 |

| Atherosclerotic conditions | 0.71 | 0.56–0.90 | .005 |

| Liver disease | 0.95 | 0.69–1.30 | .737 |

| Dementia | 0.54 | 0.21–1.38 | .196 |

| Depression | 0.83 | 0.67–1.04 | .111 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1.16 | 0.95–1.42 | .148 |

| Renal disease | 0.83 | 0.60–1.13 | .231 |

| Immunosuppressive conditions | 1.05 | 0.74–1.51 | .774 |

| No. of 30-d supply equivalent prescriptions for nonpsoriasis medications | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | .074 |

| RxHCC score, mean | 0.94 | 0.78–1.13 | .496 |

| Index year | |||

| 2010 | Ref | ||

| 2011 | 0.95 | 0.81–1.11 | .515 |

| Index biologic | |||

| Etanercept | 0.51 | 0.39–0.68 | <.001 |

| Infliximab | 1.20 | 0.85–1.71 | .303 |

| Ustekinumab | Ref | ||

| Adalimumab | 0.85 | 0.65–1.12 | .260 |

Rheumatologic disease category excludes rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerotic conditions category includes cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Immunosuppressive conditions include HIV/AIDS, cancer, and metastatic solid tumor.

CI, Confidence interval; Ref, reference group; RxHCC, prescription drug hierarchical condition category.

Factors associated with discontinuation largely mirrored those associated with adherence (Table IV). In addition, residence in the Northeast (compared with the Midwest) and use of fewer nonpsoriasis medications at baseline were associated with higher odds of discontinuing the index biologic. Those on etanercept and adalimumab as their index biologic had significantly higher odds of discontinuation compared with ustekinumab users.

Table IV.

Odds of discontinuation in Medicare beneficiaries receiving biologics for psoriasis

| Discontinuation (90 d)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age category, y | |||

| <65 | 1.37 | 1.06–1.77 | .015 |

| 65–69 | Ref | ||

| 70–74 | 1.23 | 0.95–1.60 | .120 |

| 75–79 | 1.52 | 1.09–2.11 | .013 |

| ≥80 | 1.49 | 1.05–2.10 | .024 |

| Sex, male | 0.73 | 0.62–0.86 | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 1.11 | 0.80–1.55 | .525 |

| Hispanic | 0.80 | 0.51–1.25 | .326 |

| Other/unknown | 1.02 | 0.71–1.47 | .911 |

| Census region | |||

| Northeast | Ref | ||

| Midwest | 0.66 | 0.50–0.86 | .002 |

| South | 0.89 | 0.69–1.14 | .353 |

| West | 0.79 | 0.59–1.04 | .088 |

| County-level characteristics | |||

| Income, per capita, $10,000s | 0.95 | 0.85–1.06 | .333 |

| Dermatologists/10,000 residents | 1.15 | 0.81–1.62 | .437 |

| Low-income subsidy status | |||

| Full | Ref | ||

| Partial | 2.09 | 1.11–3.93 | .023 |

| None | 1.96 | 1.51–2.55 | <.001 |

| Mixed (switched status) | 4.29 | 1.94–9.48 | <.001 |

| Drug benefit type | |||

| Enhanced alternative | Ref | ||

| Basic alternative | 0.98 | 0.77–1.24 | .839 |

| Defined standard benefit | 0.86 | 0.60–1.23 | .402 |

| Actuarially equivalent standard | 1.12 | 0.85–1.47 | .436 |

| Unknown | 0.93 | 0.59–1.44 | .733 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.06 | 0.59–1.90 | .859 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.00 | 0.74–1.37 | .990 |

| Diabetes | 1.06 | 0.88–1.28 | .572 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.93 | 0.78–1.10 | .384 |

| Hypertension | 0.98 | 0.82–1.18 | .851 |

| Obesity | 1.08 | 0.84–1.38 | .570 |

| Atherosclerotic conditions | 1.28 | 1.02–1.61 | .033 |

| Liver disease | 1.27 | 0.94–1.72 | .120 |

| Dementia | 1.56 | 0.70–3.48 | .276 |

| Depression | 1.20 | 0.97–1.49 | .100 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0.83 | 0.68–1.01 | .066 |

| Renal disease | 0.93 | 0.69–1.25 | .610 |

| Immunosuppressive conditions | 1.15 | 0.81–1.63 | .430 |

| No. of 30-d supply equivalent prescriptions for nonpsoriasis medications | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | .020 |

| RxHCC score, mean | 1.14 | 0.95–1.37 | .159 |

| Index year | |||

| 2010 | Ref | ||

| 2011 | 1.10 | 0.94–1.28 | .258 |

| Index biologic | |||

| Etanercept | 2.18 | 1.64–2.90 | <.001 |

| Infliximab | 1.41 | 0.99–2.02 | .060 |

| Ustekinumab | Ref | ||

| Adalimumab | 1.60 | 1.20–2.13 | .001 |

Rheumatologic disease category excludes rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerotic conditions category includes cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Immunosuppressive conditions include HIV/AIDS, cancer, and metastatic solid tumor.

CI, Confidence interval; Ref, reference group; RxHCC, prescription drug hierarchical condition category.

The odds of switching to a new biologic within 90 days of discontinuing the index biologic were higher among disabled beneficiaries, females, and those who switched LIS status during the study period (compared with those with full LIS coverage) (Appendix Table II; available at http://www.jaad.org). Compared with index users of ustekinumab, index users of all 3 remaining biologics had higher odds of switching. After a gap of at least 90 days, odds of restarting biologic therapy were lower among beneficiaries living in the Midwest, South, and West (compared with those in the Northeast); patients with full LIS (compared with non-LIS status); and index users of adalimumab (compared with index users of ustekinumab).

Appendix Table II.

Multinomial logistic regression results for switchers, restarters, and other discontinuers of index biologic (compared with continuing users of index biologic)

| Switcher

|

Restarter

|

Other discontinuer

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age category, y | |||||||||

| <65 | 1.84 | 1.13–3.00 | .014 | 1.50 | 0.95–2.35 | .079 | 1.21 | 0.90–1.62 | .207 |

| 65–69 | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| 70–74 | 1.52 | 0.92–2.51 | .106 | 0.96 | 0.59–1.56 | .863 | 1.26 | 0.93–1.70 | .130 |

| 75–79 | 0.79 | 0.36–1.72 | .547 | 1.42 | 0.79–2.54 | .240 | 1.71 | 1.19–2.46 | .004 |

| ≥80 | 0.77 | 0.35–1.70 | .513 | 1.34 | 0.73–2.47 | .341 | 1.70 | 1.16–2.49 | .006 |

| Sex, male | 0.64 | 0.47–0.88 | .005 | 0.96 | 0.72–1.27 | .764 | 0.70 | 0.58–0.84 | <.001 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Black | 1.27 | 0.71–2.29 | .417 | 1.05 | 0.59–1.88 | .860 | 1.10 | 0.75–1.60 | .639 |

| Hispanic | 1.03 | 0.45–2.37 | .944 | 0.79 | 0.36–1.72 | .549 | 0.74 | 0.42–1.28 | .275 |

| Other/unknown | 0.60 | 0.27–1.35 | .216 | 1.42 | 0.79–2.53 | .239 | 1.03 | 0.68–1.57 | .887 |

| Census region | |||||||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Midwest | 0.67 | 0.41–1.10 | .113 | 0.52 | 0.33–0.81 | .004 | 0.72 | 0.52–0.99 | .045 |

| South | 0.78 | 0.49–1.25 | .307 | 0.59 | 0.39–0.89 | .012 | 1.08 | 0.80–1.45 | .634 |

| West | 0.89 | 0.54–1.46 | .637 | 0.52 | 0.32–0.82 | .006 | 0.89 | 0.64–1.23 | .485 |

| County-level characteristics | |||||||||

| Income, per capita, $10,000s | 1.02 | 0.83–1.25 | .850 | 0.91 | 0.76–1.09 | .300 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.07 | .357 |

| Dermatologists/10,000 residents | 1.04 | 0.54–1.99 | .916 | 1.42 | 0.80–2.53 | .234 | 1.08 | 0.73–1.61 | .704 |

| Low-income subsidy status | |||||||||

| Full | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Partial | 0.77 | 0.17–3.42 | .726 | 1.88 | 0.67–5.29 | .233 | 2.68 | 1.35–5.35 | .005 |

| None | 1.50 | 0.92–2.45 | .109 | 1.72 | 1.08–2.75 | .022 | 2.25 | 1.66–3.05 | <.001 |

| Mixed (switched status) | 3.83 | 1.12–13.13 | .033 | 3.04 | 0.89–10.33 | .075 | 5.05 | 2.15–11.83 | <.001 |

| Drug benefit type | |||||||||

| Enhanced alternative | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Basic alternative | 0.84 | 0.54–1.30 | .431 | 1.24 | 0.80–1.93 | .329 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.24 | .685 |

| Defined standard benefit | 0.51 | 0.26–1.00 | .051 | 1.09 | 0.58–2.08 | .785 | 0.94 | 0.62–1.44 | .775 |

| Actuarially equivalent standard | 0.71 | 0.43–1.17 | .179 | 1.34 | 0.82–2.20 | .248 | 1.22 | 0.89–1.67 | .219 |

| Unknown | 0.77 | 0.33–1.79 | .544 | 1.10 | 0.49–2.47 | .818 | 0.93 | 0.57–1.52 | .764 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.37 | 0.50–3.73 | .541 | 0.95 | 0.32–2.79 | .919 | 1.00 | 0.51–1.98 | .997 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.70 | 0.35–1.41 | .313 | 1.01 | 0.61–1.69 | .959 | 1.07 | 0.75–1.52 | .711 |

| Diabetes | 0.82 | 0.57–1.17 | .273 | 1.24 | 0.89–1.73 | .196 | 1.06 | 0.86–1.32 | .574 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.90 | 0.65–1.26 | .543 | 0.83 | 0.61–1.13 | .224 | 0.97 | 0.79–1.19 | .756 |

| Hypertension | 0.90 | 0.64–1.27 | .537 | 1.07 | 0.77–1.49 | .695 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.22 | .896 |

| Obesity | 1.13 | 0.71–1.78 | .616 | 1.09 | 0.71–1.66 | .695 | 1.06 | 0.79–1.42 | .714 |

| Atherosclerotic conditions | 1.29 | 0.83–2.00 | .258 | 1.66 | 1.14–2.41 | .008 | 1.16 | 0.90–1.51 | .257 |

| Liver disease | 1.43 | 0.84–2.43 | .187 | 1.00 | 0.58–1.72 | .999 | 1.33 | 0.94–1.88 | .109 |

| Dementia | 0.88 | 0.11–7.20 | .908 | 1.38 | 0.41–4.68 | .603 | 1.71 | 0.71–4.10 | .229 |

| Depression | 1.17 | 0.80–1.73 | .422 | 1.48 | 1.03–2.12 | .033 | 1.12 | 0.87–1.44 | .390 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0.92 | 0.64–1.33 | .656 | 0.94 | 0.67–1.33 | .743 | 0.77 | 0.62–0.97 | .027 |

| Renal disease | 1.13 | 0.63–2.01 | .692 | 1.07 | 0.65–1.76 | .792 | 0.83 | 0.59–1.18 | .310 |

| Immunosuppressive conditions | 0.97 | 0.47–1.97 | .925 | 1.09 | 0.59–2.02 | .785 | 1.23 | 0.83–1.81 | .306 |

| No. of 30-d supply equivalent prescriptions for nonpsoriasis medications | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | .933 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.01 | .136 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | .011 |

| Mean RxHCC score | 0.96 | 0.68–1.35 | .792 | 1.07 | 0.78–1.46 | .694 | 1.23 | 1.00–1.52 | .056 |

| Index year | |||||||||

| 2010 | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| 2011 | 1.10 | 0.82–1.48 | .533 | 1.13 | 0.86–1.50 | .385 | 1.08 | 0.90–1.30 | .406 |

| Index biologic | |||||||||

| Etanercept | 7.48 | 2.97–18.82 | <.001 | 0.94 | 0.62–1.42 | .769 | 2.69 | 1.89–3.82 | <.001 |

| Infliximab | 3.20 | 1.11–9.19 | .031 | 0.83 | 0.48–1.44 | .509 | 1.72 | 1.12–2.66 | .014 |

| Ustekinumab | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Adalimumab | 6.20 | 2.46–15.60 | <.001 | 0.54 | 0.35–0.82 | .004 | 2.04 | 1.43–2.90 | <.001 |

Switcher indicates patients beginning treatment with a new biologic within 90 d of discontinuing the index biologic. Restarter indicates patients resuming treatment with the index biologic or a new biologic after 90 d of discontinuing the index biologic. Other discontinuer indicates patients with discontinuation of index biologic and no resumption of treatment before the end of the follow-up period. Rheumatologic disease category excludes rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerotic conditions category includes cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Immunosuppressive conditions include HIV/AIDS, cancer, and metastatic solid tumor.

CI, Confidence interval; Ref, reference group; RxHCC, prescription drug hierarchical condition category.

DISCUSSION

This study adds to the literature by examining biologic treatment patterns among a national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis. Overall, slightly over one third of the patients were adherent to their index biologic and almost half discontinued within 12 months of initiation. Only 8% of patients switched to another biologic, and 9% restarted biologic treatment (with either the index biologic or an alternate).

Our estimates of the adherence and discontinuation rates for biologics among Medicare beneficiaries with psoriasis exhibit some similarities and differences from what has been reported in the literature. However, it is difficult to directly compare estimates because differences in study populations may explain some observed variation. Compared with younger privately insured populations that have been the focus of prior research in the United States, Medicare beneficiaries are more likely to have had psoriasis for a longer period of time and/or be disabled, to have more comorbidities and competing health priorities, and to have different drug cost-sharing arrangements. Methodological differences among studies, particularly regarding definitions of discontinuation (eg, gaps ranging from 45–130 days), also contribute to differences in findings.6–8,26 Examination of factors associated with adherence and discontinuation revealed both expected and novel findings. Similar to other studies,26,27 we found that being female was associated with less persistent treatment. It is unclear whether this is the result of an underlying biological cause, a health care delivery issue (eg, differences in patient-provider interaction), or other factors. Our finding that adherence was lower and discontinuation was higher in individuals who were not eligible for LIS (and thus faced substantial cost sharing under Medicare Part D) is consistent with prior studies that have found similar treatment patterns in privately insured individuals who face higher out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs indicated for various chronic conditions.28–31 The associations we observed between atherosclerotic conditions and census region and adherence and/or discontinuation rates suggests a need for future research to identify the reasons for these variations.

Finally, we found substantial variation in both adherence and discontinuation rates by index biologic. Interestingly, our results suggest that patients using etanercept were less likely to be adherent and patients using etanercept and adalimumab, both self-administered biologics, were more likely to discontinue compared with those on ustekinumab, which during our study period was administered under the supervision of a physician. This may partly reflect greater awareness of adherence problems (ie, missed appointments indicate missed doses) and thus greater opportunity for intervention when patients are receiving treatment in the office. On the other hand, patients on ustekinumab, the newest treatment option on the market at the time of study, were likely to have been on and failed other biologic therapies in the past (beyond the 12-month preindex period observed in our study); thus a lack of alternative therapeutic options may have driven treatment persistence. Although the reasons for these differences across biologics deserve further investigation, it is notable that all biologic agents including ustekinumab had high levels of nonadherence and discontinuation in our study.

Several limitations should be noted. As a retrospective insurance claims-based study, details on treatment response, side effects, and reasons for nonadherence or gaps in treatment were unavailable. As such, we were unable to determine if treatment discontinuation was deliberate and appropriate, for example as a result of adverse effect or loss of efficacy.32 In addition, unobserved covariates (eg, patient preferences) may have confounded the relationship between measured variables and biologic use patterns. Although rigorous, our measures are also subject to some limitations. First, we used several proxies of comorbidity status but did not have access to primary measures of psoriasis severity beyond the fact that biologics are indicated for moderate to severe disease. Second, although PDC reflects availability of medication supply, it does not capture whether patients use their medication supply as directed and has the potential to overestimate actual adherence to self-administered medications. Similarly, if prescribers increased the dosing frequency for clinician-administered biologics to overcome loss of response, which has been shown previously for infliximab dosing,33 our calculation of assigned days’ supply using the standard dosing schedule would have overestimated adherence if patients missed an interim dose. Third, we were unable to determine whether those who discontinued treatment eventually restarted after our study period ended. Finally, as with all claims analyses, data may be subject to coding errors.

Despite these limitations, our findings indicate low biologic adherence and high discontinuation rates in Medicare patients treated for psoriasis. Prior data suggest that interruption of biologic treatment for psoriasis is associated with poorer outcomes compared with continuous therapy,34 so understanding the reasons for treatment discontinuation will be important. Future patient- and provider-centered research examining treatment decision-making is essential to more deeply explore factors that may be contributing to the utilization patterns we observed, and to inform interventions to promote adherence and persistence to biologic therapies for psoriasis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from Amgen Inc. Dr Gelfand received salary support from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases K24AR064310. Dr Takeshita received salary support from a Dermatology Foundation Career Development Award.

The authors thank Amy R. Pettit, PhD, consultant and adjunct fellow, University of Pennsylvania Center for Public Health Initiatives, for her feedback on the manuscript and editorial assistance and Vrushabh P. Ladage, BS, University of Pennsylvania, for his editorial assistance. Dr Pettit and Mr Ladage have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr Doshi has served as a consultant and/or advisory board member for Alkermes Inc, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest Laboratories, Merck, and Shire, receiving honoraria; had grants from Amgen Inc (relevant to this study), Humana Inc, Merck & Co Inc, Pfizer Inc, PhRMA, and National Pharmaceutical Council; and has a spouse who holds stocks in Merck & Co Inc and Pfizer Inc. Dr Takeshita has received grant funding from Pfizer Inc and received payment for CME work related to psoriasis. Mr Pinto is an employee of and shareholder of Amgen Inc. Dr Viswanathan was an employee and shareholder of Amgen Inc at the time of the study and is now an employee and shareholder of Allergan plc. Dr Gelfand served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen Inc, Coherus, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics (formerly Centocor), Merck & Co Inc, Novartis Corp, and Pfizer Inc, receiving honoraria; had grants or has pending grants from AbbVie, Amgen Inc, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, and Pfizer Inc; and received payment for CME work related to psoriasis. Dr Yu was an employee at the University of Pennsylvania at the time of the study; she is now an employee of IMS Health. Dr Li and Ms Rao have no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1173–1179. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, Vreeland MG, Wu Y. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(6):383–392. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman SR, Burudpakdee C, Gala S, Nanavaty M, Mallya UG. The economic burden of psoriasis: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(5):685–705. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.933671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chastek B, Fox KM, Watson C, Gandra SR. Etanercept and adalimumab treatment patterns in psoriatic arthritis patients enrolled in a commercial health plan. Adv Ther. 2012;29(8):691–697. doi: 10.1007/s12325-012-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Fox KM, Watson C, Gandra SR. Treatment patterns with etanercept and adalimumab for psoriatic diseases in a real-world setting. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(5):369–373. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.755255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Z, Carter C, Wilson KL, Schenkel B. Ustekinumab dosing, persistence, and discontinuation patterns in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(2):113–120. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.883059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Q, Carter C, AbuDagga A, et al. Real-world dosing and utilization of ustekinumab among patients with psoriasis. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2014;6(3):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeshita J, Gelfand JM, Li P, et al. Psoriasis in the U.S. Medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(12):2955–2963. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(1):146–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grozdev IS, Van Voorhees AS, Gottlieb AB, et al. Psoriasis in the elderly: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007;10(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li P, Blum MA, Von Feldt J, Hennessy S, Doshi JA. Adherence, discontinuation, and switching of biologic therapies in Medicaid enrollees with rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health. 2010;13(6):805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harley CR, Frytak JR, Tandon N. Treatment compliance and dosage administration among rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving infliximab, etanercept, or methotrexate. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(6 Suppl):S136–S143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang B, Rahman M, Waters HC, Callegari P. Treatment persistence with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab in combination with methotrexate and the effects on health care costs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(08)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296(14):1735–1741. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the general practice research database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):1000–1006. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azfar RS, Seminara NM, Shin DB, Troxel AB, Margolis DJ, Gelfand JM. Increased risk of diabetes mellitus and likelihood of receiving diabetes mellitus treatment in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(9):995–1000. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan J, Wang S, Haynes K, Denburg MR, Shin DB, Gelfand JM. Risk of moderate to advanced kidney disease in patients with psoriasis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robst J, Levy JM, Ingber MJ. Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare prescription drug plan payments. Health Care Financ Rev. 2007;28(4):15–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P, McElligott S, Bergquist H, Schwartz JS, Doshi JA. Effect of the Medicare Part D coverage gap on medication use among patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):776–784. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00004. W-263, W-264, W-265, W-266, W-267, W-268, W-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doshi JA, Li P, Puig A. Impact of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 on utilization and spending for Medicare Part B-covered biologics in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(3):354–361. doi: 10.1002/acr.20010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donohue JM, Morden NE, Gellad WF, et al. Sources of regional variation in Medicare Part D drug spending. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):530–538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1104816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P, Metlay JP, Marcus SC, Doshi JA. Factors associated with antimicrobial drug use in Medicaid programs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(5):829–832. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.130493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esposito M, Gisondi P, Cassano N, et al. Survival rate of antitumor necrosis factor-alpha treatments for psoriasis in routine dermatological practice: a multicentre observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(3):666–672. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gniadecki R, Bang B, Bryld LE, Iversen L, Lasthein S, Skov L. Comparison of long-term drug survival and safety of biologic agents in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(1):244–252. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curkendall S, Patel V, Gleeson M, Campbell RS, Zagari M, Dubois R. Compliance with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: do patient out-of-pocket payments matter? Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1519–1526. doi: 10.1002/art.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karaca-Mandic P, Joyce GF, Goldman DP, Laouri M. Cost sharing, family health care burden, and the use of specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 Pt 1):1227–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer L, Abouzaid S, Shi N, et al. Impact of patient cost sharing on multiple sclerosis treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2012;4:SP28–SP36. Special Issue. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung H, Wan J, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Patient-reported reasons for the discontinuation of commonly used treatments for moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeshita J, Wang S, Shin DB, et al. Comparative effectiveness of less commonly used systemic monotherapies and common combination therapies for moderate to severe psoriasis in the clinical setting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brezinski EA, Armstrong AW. Off-label biologic regimens in psoriasis: a systematic review of efficacy and safety of dose escalation, reduction, and interrupted biologic therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]