Abstract

This paper describes the theoretical foundation, development, and feasibility testing of an online, evidence-based intervention for teen dating violence prevention designed for dissemination. Teen Choices: A Program for Healthy, Non-Violent Relationships relies on the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change and expert system technology to deliver assessments and feedback matched to stage of change for using healthy relationship skills. The program also tailors feedback to dating status, risk level, and other key characteristics. Ninety-nine students from high schools in Tennessee and Rhode Island completed a Teen Choices session and 97 completed an 11-item acceptability evaluation. 100% of participants completed the intervention session as intended. Evaluations of the program were favorable. For example, 88.7% agreed the program feedback was easy to understand, and 86.7% agreed that the program could help people develop healthier relationships. Findings provide encouraging evidence of the acceptability and feasibility of this approach to dating violence prevention.

Keywords: dating violence prevention, adolescence, stages of change, relationship skills, computerized intervention

Researchers first began to examine violence among unmarried couples in the early 1980’s, following Makepeace’s (1981) study of dating violence among college students. Makepeace found that 21% of students had experienced dating violence, and asked that researchers and policy makers reject idealized images of adolescent dating relationships and view them as a potential training ground for spousal violence. Recent studies of dating violence during the teen years find rates of victimization ranging from 9% to 65% among females and 9% to 62% among males (Bonomi et al., 2012; Rothman & Xuan, 2014). Some of the divergence in estimates across studies can be attributed to differences in the operational definition of “violence” (e.g., whether the definition also includes psychological abuse and/or mild forms of violence) and the time frames examined (e.g., last year, since age 13) (Hickman, Jaycox, & Aronoff, 2004; Lewis & Fremouw, 2001).

Initially, many researchers were surprised to find that in a majority of dating violence cases the violence was reciprocal—that is, both partners perpetrated and sustained aggression. Experiencing violence from one’s partner is the strongest predictor of expressed violence, surpassing the influence of violence in family of origin and among peers (Clark, Beckett, Wells, & Dungee-Anderson, 1994; Gray & Foshee, 1997; Magdol et al., 1997). For both males and females, longitudinal research shows that dating violence victimization is associated with increased risk for depression, suicidal ideation, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and a range of other adverse outcomes (Ackard, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007; Roberts, Klein, & Fisher, 2003; Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013; Foshee, Reyes, Gottfredson, Chang, & Ennett, 2013), as well as with increased risk for dating violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood (Cui, Ueno, Gordon, & Fincham, 2013). Female victims of dating violence face additional risks: 10% of intentional injuries among adolescent girls (Sege, Stigol, Perry, Goldstein, & Spivak, 1996) and 3% of homicides (Catalano, Smith, Snyder, & Rand, 2009) are the result of violence from a partner. The serious and lasting consequences of dating violence for both male and females point to the importance of prevention and early intervention.

Traditional Teen Dating Violence Prevention Programs

Today, 21 states in the U.S. have laws that encourage or require school districts to develop and/or offer a curriculum on teen dating violence; an additional 4 states have legislation pending (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014). Most of the dating violence prevention programs described in the literature seek to increase awareness about teen dating violence, its warning signs, and services available, and to change gender stereotypes and other attitudes supporting violence against women. Many also seek to change behavior by teaching relationship skills that are healthy alternatives to violence and abuse. However, the evidence supporting interventions for dating violence prevention is mixed (Leen et al., 2013; Liu, Binbin, & Ma, 2014; Lundgren & Amin, 2015; Fellmeth, Heffernan, Nurse, Habibula, & Sethi, 2013). A recent meta-analysis of 38 outcome studies found no evidence that dating violence prevention programs reduce dating violence or produce positive changes in skills, attitudes, or behavior (Fellmeth et al., 2013). A major problem with existing programs is that they are curriculum-based and “one-size-fits-all,” neglecting individual differences in dating history, dating violence experiences, gender, and readiness to use healthy relationship skills to stay violence-free. In addition, the best evidence-based programs—Fourth R: Skills for Youth Relationships (Wolfe et al., 2009) and Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 1998; Foshee et al., 2000)—can be challenging to deliver with fidelity, as they require 10–21 class periods, additional school-wide events, and significant teacher time for training and program delivery.

Teen Choices: A Program for Healthy, Non-Violent Relationships

When developing an intervention, it is critical to design for dissemination—that is, to maximize the likelihood that the intervention will be feasible and sustainable in real-world settings, and acceptable to end users (Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003; Prochaska, Mauriello, Dyment, & Gokbayrak, 2011). Built with dissemination in mind, the Teen Choices program relies on computers and expert system technology to deliver the intervention efficiently, cost-effectively, and with fidelity. Following pre-programmed decision rules, it delivers individualized feedback and guidance matched to the end user’s dating history, dating violence experiences, gender, and stage of readiness to use healthy relationship skills, based on an evidence-based model of health behavior change—the Transtheoretical Model (TTM). In addition, high school students were involved in each step of the program’s development to ensure that the program would resonate with and be acceptable to end users. The remainder of this paper describes the program’s theoretical approach, steps in its development, and the results of a feasibility test assessing the acceptability of the program to high schools students.

A focus on healthy relationship skills

At the outset, it was decided that Teen Choices, like several state-of-the-art teen dating violence prevention programs (Foshee et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 2009; Ball et al., 2012), would focus on “using healthy relationship skills” as the primary behavior change goal. Skill deficits have been linked theoretically (Brendgen, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Lavoie, 2001; Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004) and empirically (Dye & Eckhardt, 2000; Foshee, Benefield, Ennett, Bauman, & Suchindran, 2004; Rothman, Johnson, Azrael, Hall, & Weinberg, 2010) to dating violence among adolescents and college students. The focus on healthy relationship skills is appropriate for—and can be beneficial to—most students, including daters who have not experienced or perpetrated dating violence, and non-daters. To make the Teen Choices intervention salient and engaging for non-daters, non-daters are encouraged to focus on healthy relationship skills with peers. Relationships with same-sex peers serve as the foundation for experiences in romantic relationships (Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002; Lempers & Clark-Lempers, 1993). Affiliative qualities so important in romantic relationships, such as collaboration, conflict resolution, and emotional intimacy, are developed first with same-sex peers (Buhrmester, 1990; Feiring, 1999).

The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM)

The program is based on the TTM, which has been shown to be robust in its ability to explain and facilitate change across a broad range of behaviors and populations. Research on the TTM has found that behavior change involves progress through a series of stages: Precontemplation (not ready), Contemplation (getting ready), Preparation (ready), Action (making behavioral changes), and Maintenance (maintaining changes) (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). The model includes additional dimensions central to change:

Decisional balance – the pros and cons associated with a behavior’s consequences (Janis & Mann, 1977)

Processes of change – 10 cognitive, affective, and behavioral activities that facilitate progress through the stages of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1985)

Self-efficacy – confidence to make and sustain changes in difficult situations, and temptation to slip back into old patterns (Bandura, 1977)

More than 35 years of research on the TTM have identified particular principles and processes of change that work best in each of the stages to facilitate progress. TTM stage-matched interventions have been found effective across dozens of behaviors and populations, including smoking cessation (Velicer, Prochaska, & Redding, 2006), domestic violence cessation (Levesque, Ciavatta, Castle, Prochaska, & Prochaska, 2012), bullying prevention (Evers, Prochaska, Van Marter, Johnson, & Prochaska, 2007), and depression management (Levesque et al., 2011). A meta-analysis of health interventions found that those tailored to the appropriate stage of change produced significantly greater effects than those that were not tailored to stage of change (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007).

The following steps are required in the application of the TTM to a new behavior and/or population: 1) developing psychometrically sound and externally valid measures of the model’s core constructs for the new behavior and/or population; 2) model testing to assess the applicability of the TTM to the new behavior and/or population by examining how well the TTM constructs and the established relationships between them characterize the process of change; 3) using the data to establish decision rules and cutoff scores to guide intervention development; 4) developing the TTM-based intervention; 5) assessing the feasibility of this intervention approach; 6) assessing the intervention’s efficacy in a randomized controlled trial; and 7) disseminating the intervention. Based on data provided by over 943 high school students, steps 1–3, described elsewhere (Levesque, 2007), provided the empirical foundation for this work. Steps 4–5 are presented in the remainder of this paper.

Intervention development

To identify ideas representing each of the major constructs of the TTM for using healthy relationship skills to prevent teen dating violence (stage of change, decisional balance, processes of change, self-efficacy), a literature review, interviews with four experts on teen dating violence, and seven focus groups with a total of 64 teens recruited from high schools and Boys and Girls Clubs in Rhode Island and Georgia were conducted. In addition, a content-analysis was conducted on five empirically supported dating violence prevention programs (Rosenbluth, 2004; Foshee & Langwick, 2004; Wolfe et al., 1996; Lavoie, Gosselin, Robitaille, & Vezina, 1995; Kraizer & Larson, 1996). The goals of the qualitative work were to identify key curriculum content and best practices for teen dating violence prevention, to match content and practices to the TTM principles and processes of change, and to organize them within the stage framework provided by TTM and the data-based decision rules. The integration of key content and best practices from existing programs also helps to ensure that the Teen Choices program is consistent with and can be used in conjunction with other high-quality programs simultaneously or sequentially.

Another task in the formative research was to identify and operationally define “healthy relationship skills.” In the Teen Choices program, “using healthy relationship skills” is defined as follows:

Trying to understand and respect the other person's feelings and needs;

Using calm, nonviolent ways to deal with disagreements (for example, leaving the room to cool down, offering solutions);

Respecting the other person's boundaries (for example, how close they want to get and what they're comfortable and uncomfortable doing);

Communicating your own feelings and needs clearly and respectfully; and

Making decisions that you know are good for you in relationships.

Cross-sectional data showed that males are significantly more likely than females to be in an early stage of change for using these healthy relationship skills, and that males and females in the early stages report significantly more incidents of dating violence perpetration and victimization in the past year (Levesque, 2007).

At various stages in its development, the program was reviewed by four dating violence experts, a cultural sensitivity expert, two high school health teachers, a high school guidance counselor, a program director at a local Boys’ and Girls’ Club, and several staff at a juvenile detention center. In addition, three focus groups with a total of 22 teens recruited from Boys’ and Girls’ clubs were conducted to get feedback on the look and feel of the program, the introduction, draft feedback paragraphs, and sample images. Finally, usability tests were conducted with six teens to ensure that the program was easily navigable and that assessments and exercises were successfully completed.

Intervention structure

The Teen Choices protoype was a single-session expert system session with three intervention tracks to meet the unique needs of: 1) high-risk daters (i.e., teens who had experienced or perpetrated any physical dating abuse and/or multiple incidents of emotional abuse in the past year, and so were at higher risk of future abuse); 2) low-risk daters; and 3) non-daters. The program compiles text paragraphs and images to provide immediate feedback as the participant progresses through the session. Approximately 1200 paragraphs were used, resulting in over 20,000 unique feedback sessions. The interactive session, which included assessment and individualized feedback, lasted about 25–30 minutes. Its Flesch-Kincaid reading level was grade 7.0.

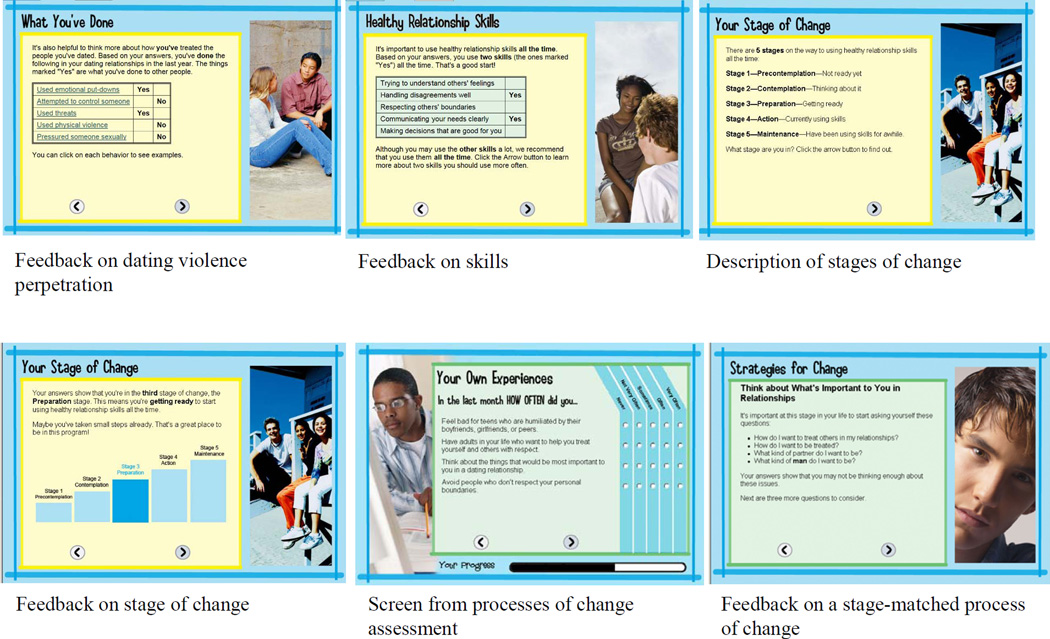

The program flow was as follows: 1) title screen and login; 2) introduction and consent to use the program; 3) assessment of demographics and dating history; 4) dating violence (if dated in the past year) or peer violence (if did not date in the past year) assessment and feedback; 5) assignment to intervention track based on dating history and violence experienced and perpetrated; 6) assessment and feedback on healthy relationship skills, including additional information on two skills the participant was using the least; 7) assessment and feedback on stage of change for using healthy relationship skills and up to five stage-matched principles and process of change; 8) assessment and feedback on level of alcohol use and its relationship to teen dating and peer violence; 9) assessment and feedback on readiness to seek help if a victim or perpetrator of dating violence or peer violence; and 10) readiness to offer help to others who are victims or perpetrators of dating violence or peer violence. An expert system software program, called TTMX (Transtheoretical Model Expert), administered the Teen Choices assessments, scored them, and followed programmed decision rules to deliver individualized feedback and guidance with fidelity. Sample screenshots from the interactive program are included in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample Screenshots from the Teen Choices Program

Feasibility Test

Method

Participants

Participants were 99 students recruited from a high school in Tennessee (n=44) and a high school in Rhode Island (n=55). The sample represented approximately 75% of students who received parental consent forms. The remainder did not return the consent form by the due date. No parental refusals were received. Fifty-six percent of participants were female; 57% were White, non-Hispanic, 30% Black, non-Hispanic, 8% Hispanic, and 5% other or multiracial. Thirty-four percent of the sample was in grade 9, 22% in grade 10, and 13% in grade 11, and 30% in grade 12. Thirty-one percent received free or reduced-price lunch. Eighty percent had dated in the last year, and 49% were currently dating. Nine percent were in the Precontemplation stage for using healthy relationship skills, 25% in the Contemplation stage, 8% Preparation, 50% Action, and 8% Maintenance.

Procedure

All study procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board. Pilot sessions were conducted in school computer labs. An 11-item evaluation tool, administered by the Teen Choices program at the end of the intervention session, included questions adapted from the National Cancer Institute’s Education Materials Review Form (National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Communication, 1989) and a measure used to evaluate other tailored health behavior change interventions (Rimer et al., 1994), and additional questions developed for this study. In addition, three open-ended questions asked, “What did you like least about the program?” “What did you like most about the program?” and “Do you have any ideas about how we could improve the program?”

Two criteria were selected for establishing feasibility: 1) at least 90% of participants who received the intervention in the classroom would complete the session; and 2) all statements on the acceptability evaluation would receive a score of 4 or higher ("agree" or "strongly agree”) from at least 75% of participants. Finally, qualitative responses to open-ended questions were examined to identify what participants liked least and most about the program, and how the program could be improved.

Results

All 99 participants (100%) completed the Teen Choices session, and 97 (98%) completed the acceptability evaluation. Responses to the program were very positive. Table I presents the percentage of students giving responses of 4 or higher for each of the acceptability questions. Percentages ranged from 69% to 89%, with a mean of 81% across questions. “I would recommend this program to a friend” was the only item endorsed by less than 75% of users.

Table I.

Acceptability of the Teen Choices Program (N=97)

| Evaluation Questions | Percent Agree or Strongly Agree |

|---|---|

| The program was easy to use. | 83.5% |

| The questions were easy to understand. | 87.6% |

| The personal feedback was easy to understand. | 88.7% |

| I like the way the program looked. | 84.5% |

| The program was designed for people my age. | 86.6% |

| The program was interesting. | 80.4% |

| I enjoyed using the program. | 75.3% |

| The program gave me new things to think about. | 78.4% |

| The program could help people develop healthier relationships. | 86.6% |

| I would recommend this program to a friend. | 69.1% |

| I would be willing to use this program again in 2 months. | 75.3% |

In response to the first open-ended question, “What did you like least about the program?” 65% described elements they didn’t like; 11% listed things they liked, and 24% gave a neutral response or no response at all. Participants were most likely to state that they thought the program was too long or had too many questions (16%) and that it was too personal (12%). For example, students wrote:

All of the questions and there were a lot of them.

The part on alcohol. It made me feel a little ashamed.

Nothing. It’s a good program and I think there should be one made for younger kids so they know about dating abuse before they get to high school.

In response to the question, “What did you like most about the program?” 77% described elements they liked; 4% listed things they didn’t like, and 19% gave neutral responses or no response at all. Participants were most likely to state that the program offered helpful advice (18%) or made them think (17%). For example, students wrote:

I like the way it gave you feedback on the stages of healthy relationships! I really did enjoy this. It will help me because I do need it! I REALLY DID ENJOY IT! It was also something new to talk about! I would REALLY recommend this to a FRIEND, RELATIVE.

It gave me advice to give to others in abusive relationships.

I liked the whole program because it was easy to understand and it was enjoyable.

In response to the question, “Do you have any ideas about how we could improve the program?” 43% of pilot test participants provided a recommendation. Participants were most likely to recommend changes to the questions (13%), such as the format, and that the program provide more information or address additional topics (12%). For example:

Make more questions that we could answer in our own words.

Give examples of problems.

Add little videos or clips of people who have had these things happen to them.

Discussion

This paper described the theoretical approach, development, and feasibility testing of Teen Choices, and online intervention for teen dating violence prevention. Virtually every step in the process had two end goals in mind: maximizing efficacy and maximizing disseminability. How can we build an intervention that is effective and also feasible and sustainable in real world settings and acceptable to end users? The feasibility test demonstrates that Teen Choices can be delivered reliably and is acceptable to end users. One hundred percent of participants completed the intervention session, and 10 of the 11 positive statements on the acceptability evaluation received a score of 4 or higher (“agree” or “strongly agree”) from at least 75% of participants. “I would recommend this program to a friend” was the only item endorsed by less than 75% of users. It is possible that this relatively low rating represents teens’ discomfort talking to peers about dating violence, rather than doubts about the program’s potential usefulness to others, as 87% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the program could help people develop healthier relationships.

Program development has since continued, integrating feedback from end users and experts. The intervention now includes the kind of additional information and interactivity recommended by students who participated in the feasibility test. For example, the intervention now includes: 1) audio, so that all assessments and feedback are read verbatim; 2) 15 brief videos demonstrating the five healthy relationship skills (three videos per skill); 3) personal testimonials; 4) a Teen Choices website with additional information and activities; 4) a “Let’s Talk About It” webpage with school, community, and national resources. At the recommendation of experts, three additional intervention tracks were added to meet the unique needs of low-risk non-daters, high-risk non-daters, and high-risk victims. The high-risk victim track does not focus on healthy relationship skills, but instead uses a TTM approach to facilitate progress through the stages of change for “keeping yourself safe” in relationships. The full intervention package also includes guides for parents and for school implementers.

A major limitation of this feasibility study is that it provides no information on the efficacy of this approach to teen dating violence or peer violence prevention. However, the intervention has since been evaluated in a cluster-randomized trial involving 3,901 students from 20 high schools randomly assigned to the Intervention condition or a Comparison condition (Levesque, Johnson, Welch, Prochaska, & Paiva, in press; Levesque, Johnson, Welch, Prochaska, & Paiva, 2016). Students assigned to the Intervention condition received three monthly Teen Choices sessions lasting 25–30 minutes each. Among 2,605 participants who completed the one-year follow-up assessment and were exposed to risk for dating violence (i.e., they reported a past-year history of dating violence at baseline, and/or dated during the study period), the intervention was associated with significantly lower rates of emotional and physical dating violence victimization and perpetration at follow-up (Levesque et al., in press). Among 681 participants who completed the one-year follow-up and were not exposed to risk for dating violence, the intervention was associated with significantly lower rates of emotional and physical peer violence victimization and perpetration (Levesque et al., 2016).

Summary

Today, 21 states in the U.S. have laws that encourage or require school districts to develop and/or offer a curriculum on teen dating violence; an additional 4 states have legislation pending. The Teen Choices program integrates key content from the best available health education curricula for teen dating violence prevention, but goes beyond traditional curriculum-based programs by also integrating an evidence-based model of health behavior change. By assessing and intervening on behavior directly with a low-cost, convenient computerized program that is well received by students, schools have the potential to increase their impact on the students’ healthy ways of relating, and in the prevention of teen dating violence and peer violence and its consequences.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (grant no. R43CE000499). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

At the time the research was conducted, all authors were employed by Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc. and held stock and/or stock options in the company.

Reference List

- Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151(5):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball B, Tharp AT, Noonan RK, Valle LA, Hamburger ME, Rosenbluth B. Expect respect support groups: Preliminary evaluation of a dating violence prevention program for at-risk youth. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(7):746–762. doi: 10.1177/1077801212455188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Nemeth J, Bartle-Haring S, Buettner C, Schipper D. Dating violence victimization across the teen years: Abuse frequency, number of abusive partners, and age at first occurrence. Bmc Public Health. 2012;12:637. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro R, Tremblay RE, Lavoie F. Reactive and proactive aggression: predictions to physical violence in different contexts and moderating effects of parental monitoring and caregiving behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(4):293–304. doi: 10.1023/a:1010305828208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61(4):1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Female victims of violence (NCJ 228356) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Beckett J, Wells M, Dungee-Anderson D. Courtship violence among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology. 1994;20(3):264–281. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Ueno K, Gordon M, Fincham FD. The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2013;75(2):300–313. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye ML, Eckhardt CI. Anger, irrational beliefs, and dysfunctional attitudes in violent dating relationships. Violence and Victims. 2000;15(3):337–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers KE, Prochaska JO, Van Marter DF, Johnson JL, Prochaska JM. Transtheoretical-based bullying prevention effectiveness trials in middle schools and high schools. Educational Research. 2007;49(4):397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C. Other-sex friendship networks and the development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(4):495–512. [Google Scholar]

- Fellmeth GL, Heffernan C, Nurse J, Habibula S, Sethi D. Educational and skills-based interventions for preventing relationship and dating violence in adolescents and young adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004534.pub3. CD004534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V, Langwick S. Safe Dates: An adolescent dating abuse prevention curriculum. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):45–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Greene WF, Koch GG, Linder GF, MacDougall JE. The Safe Dates program: 1-year follow-up results. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(10):1619–1622. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, et al. The Safe Dates project: Theoretical basis, evaluation design, and selected baseline findings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(5):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HL, Gottfredson NC, Chang LY, Ennett ST. A longitudinal examination of psychological, behavioral, academic, and relationship consequences of dating abuse victimization among a primarily rural sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(6):723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents' working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73(1):241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HM, Foshee V. Adolescent dating violence: Differences between one-sided and mutually violent profiles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12(1):126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, Aronoff J. Dating violence among adolescents: Prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2004;5(2):123–142. doi: 10.1177/1524838003262332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis IL, Mann L. Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kraizer S, Larson CL. Dating violence: Intervention & prevention for teenagers group leader's manual. 3rd. Tulsa, OK: National Resource Center for Youth Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie F, Gosselin A, Robitaille L, Vezina L. Stop! Dating violence among adolescents: Classroom activities. Quebec, Canada: Minister of Education; 1995. (Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268207572) [Google Scholar]

- Leen E, Sorbring E, Mawer M, Holdsworth E, Helsing B, Bowen E. Prevalence, dynamic risk factors and the efficacy of primary interventions for adolescent dating violence: An international review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18(1):159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lempers JD, Clark-Lempers DS. A functional comparison of same-sex and opposite sex friendships during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8(1):89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA. A stage-based expert system for teen dating violence prevention. 2007. Final Progress Report to CDC (Grant No. R43CE000499). [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Ciavatta MM, Castle PH, Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO. Evaluation of a stage-based, computer-tailored adjunct to usual care for domestic violence offenders. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(12):368–384. doi: 10.1037/a0027501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Johnson JL, Welch CA, Prochaska JM, Paiva AL. Teen Choices: A Program for Healthy, Nonviolent Relationships: Effects on peer violence. 2016 doi: 10.1037/vio0000049. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Johnson JL, Welch CA, Prochaska JM, Paiva AL. Teen dating violence prevention: Cluster-randomized trial of Teen Choices, an online, stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships. Psychology of Violence. doi: 10.1037/vio0000049. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Van Marter DF, Schneider RJ, Bauer MR, Goldberg DN, Prochaska JO, et al. Randomized trial of a computer-tailored intervention for patients with depression. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2011;26:77–89. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090123-QUAN-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SF, Fremouw W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(1):105–127. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Binbin Y, Ma Y. Educational and skills-based interventions for preventing relationship and dating violence in adolescents and young adults. Public Health Nursing. 2014;31(5):441–443. doi: 10.1111/phn.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren R, Amin A. Addressing intimate partner violence and sexual violence among adolescents: Emerging evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(1 Suppl):S42–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makepeace J. Courtship violence among college students. Family Relations. 1981;30:97–192. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Communication. Making health communication programs work: A planner's guide. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1989. (NIH Publication No.89-1493). [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Teen dating violence. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-dating-violence.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JM, Mauriello L, Dyment S, Gokbayrak S. Designing a health behavior change program for dissemination to underserved pregnant women. Public Health Nursing. 2011;28(6):548–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Common processes of self-change in smoking, weight control, and psychological distress. In: Shiffman S, Wills T, editors. Coping and substance abuse: A conceptual framework. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, Orleans CT, Fleisher L, Cristinzio S, Resch N, Telepchak J, et al. Does tailoring matter? The impact of a tailored guide on ratings and short-term smoking-related outcomes for older smokers. Health Education Research. 1994;9(1):69–84. doi: 10.1093/her/9.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TA, Klein JD, Fisher S. Longitudinal effect of intimate partner abuse on high-risk behavior among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:875–881. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth B. Expect respect: A support group curriculum for safe and healthy relationships. Harrisburg, PA: National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Johnson RM, Azrael D, Hall DM, Weinberg J. Perpetration of physical assault against dating partners, peers, and siblings among a locally representative sample of high school students in Boston, Massachusetts. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164(12):1118–1124. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Xuan Z. Trends in physical dating violence victimization among U.S. high school students, 1999–2011. Journal of School Violence. 2014;13(3):277–290. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2013.847377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sege R, Stigol LC, Perry C, Goldstein R, Spivak H. Intentional injury surveillance in a primary care pediatric setting. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(3):277–283. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170280047008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Redding CA. Tailored communications for smoking cessation: Past successes and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25(1):49–57. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W, et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster-randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(8):692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Gough R, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Grasley C, Pittman AL, et al. The youth relationships manual: A group approach with adolescents for the prevention of woman abuse and the promotion of healthy relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(3):406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]