Short abstract

Describes the income security, health status, and health care coverage of older persons in Mexico and presents policy recommendations that may lead to increased old-age income security and health in Mexico.

Abstract

This analysis of aging and income security in Mexico establishes that the older population in Mexico is increasing quickly and that this population is especially vulnerable to poverty. Mexican citizens are living longer and overall have experienced an improvement in the quality of life compared to that of prior generations. However, this study demonstrates that social improvements are not affecting the daily lives of all persons equally. The authors attempt to uncover and highlight those differences. One of the primary challenges facing Mexico is a growing older population. The demographic transition in Mexico combined with the lack of formal sources of income in retirement place many older persons in a state of financial insecurity. The information contained in this study and the proposed policy research areas are intended to enlarge the portfolio of options for older Mexicans. The authors analyze wealth and sources of income during retirement, the relationship between health and wealth, urban and rural disparities, and the impact of migration spells to the United States on wealth accumulation and health insurance in Mexico.

Mexico is undergoing an unprecedented demographic change, with a rapidly aging population caused by a declining birthrate and improved life expectancy. Studies show that the birthrate, which has declined markedly since 1960, is expected to fall further in the decades to come and that rapid advancements in living conditions, health care, and technology are increasing life expectancy for the older Mexican population. It is critical for policy makers, the private sector, and citizens alike to understand the complexity of the phenomenon of an aging population in Mexico. Due to the Mexican Baby Boom Generation's presence in the labor market, the present day offers a window of opportunity to adapt policies regarding pensions, health care, formal sector employment, and saving for retirement before these baby boomers, born between 1980 and 2005, begin to retire in 2040.

Centro Fox, AARP, and the RAND Corporation jointly sponsored this study to contribute to the policy debate by presenting the current state of income security, health status, and health care provision in old age, as well as to encourage a deeper commitment of the public and private sectors to finding policy solutions that improve the well-being of older people in Mexico.

Study Purpose, Scope, and Approaches

An increasingly aging population can burden traditional retirement systems and health care services. The purpose of the study is primarily to take stock of where Mexico is, using available information during the 2000s. In some cases, we show historic or projected future time series and compare outcomes from Mexico with other countries to provide the context for the analysis. The scope of this study is to provide a succinct description of a number of major dimensions of the state of older people in Mexico:

The social groups least and most vulnerable to poverty

The socioeconomic status of the older population

The structure of social security programs currently in place

The private instruments available as an alternative to save for retirement

The current state of health care provision and health insurance coverage

The sources of income at older ages both when working and during retirement

The role of remittances and family transfers as sources of income in retirement

The health conditions, health care coverage, and health expenditures of the older population

We also discuss potential avenues for further research and policy analysis in Mexico. We hope that this study will generate more debate and policy analysis of this topic.

For this study, we both reviewed the relevant literature and conducted analyses using survey data. We largely relied on the most suitable and recent data set that is currently available for this analysis, the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), and supplemented it with other sources whenever appropriate. The MHAS is a nationally representative panel survey of Mexicans born before 1951 and has two waves of data, collected in 2001 and 2003. In this study, we used the 2001 data.

Findings

The Mexican Population Is Aging and the Incidence of Chronic Disease Is Rising

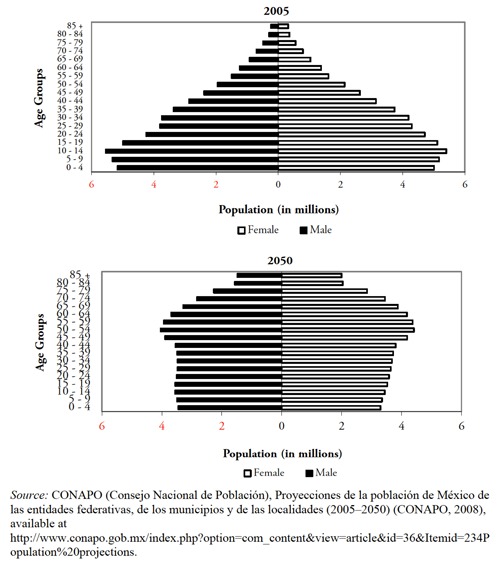

Life expectancy at birth for Mexicans increased from 36 to 74 years between 1950 and 2000 and is projected to continue increasing, with life expectancy at birth in 2050 predicted to be 80 years. At the same time, Mexico has experienced a steady decline in fertility from an average of 7 children per woman in 1960 to 2.4 in 2000. Birthrates fell from 46 per 1,000 people in 1960 to 21 births per 1,000 people in 2000. The effects of falling birthrates and increased life expectancy on the composition of Mexico's population are illustrated in Figure 1; the population pyramids reveal a gradual transformation from the 2005 triangular shape, which is characterized by a large young population, into a much more rectangular shape by 2050, implying a larger older population.

Figure 1.

Mexican Population Pyramids: 2005 and 2050

Of the 25 countries in the world with the largest older population in 2008, Mexico ranked 15th, with at least 6.7 million individuals aged 65 and older. The older population in Mexico is growing rapidly, with a 232 percent increase expected by 2040 and a higher expected increase than 10 other Latin American countries, including Brazil, Peru, and Guatemala. The United States is expected to experience a 107 percent increase over the same period.

Related to Mexico's increase in the number of older people are changes in disease patterns. Because people are living longer, chronic and degenerative diseases and disability are far more prevalent than in previous decades. In 1990, noncommunicable diseases caused 57.8 percent of deaths; this figure increased to 73.8 percent in 2004.

These demographic and epidemiological transitions raise questions about the sustainability of the current systems for providing financial security and health care for older people in Mexico.

Older People in Mexico Are Vulnerable to Poverty

According to Mexico's official food poverty measure, approximately 20 percent of the population in 2001 lived in poverty, and the poverty rate increases to almost 30 percent among those aged 65 and older. Older people living in rural areas are especially vulnerable, as they may lack the labor income and social security coverage of their urban peers. Gender also plays a role: Older men are more at risk for poverty than older women, possibly because women are more likely to receive family support in old age.

Pension and Health Care Coverage Depend on Type of Work Previously Performed

The Mexican pension and health care systems are structured in a way that allows gaps in coverage. Employees affiliated with a social security system contribute to a pension and contribute to and receive health care through their social security institution. However, coverage rates of social security are low, not only compared with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, but also compared with many other Latin American countries. In Mexico, social security contributions are not mandatory for the self-employed. The uninsured are therefore mainly found within the informal sector of the economy, which comprises self-employed people and wage earners who do not make social security contributions.

Less than half of the older Mexican population is covered by the social security system, which provides pensions and health care for individuals who have been employed for a sufficiently long period in the government or formal private sector. Workers in the formal private sector are covered by the Mexican Institute for Social Security (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social or IMSS). A subset of the formal sector consists of government employees, who are insured by the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado or ISSSTE). In 2009, ISSSTE served about 6 percent of the Mexican population, and IMSS served approximately 40 percent.

For the rest of Mexico's older people formerly or currently employed within the large informal sector, income and health care safety nets vary. Safety net noncontributory pension programs were introduced in Mexico in 2001 for the growing segment of the population that reaches retirement without social security coverage. A public health care program for the uninsured that has recently expanded substantially is Popular Health Insurance (Seguro Popular de Salud or SPS). However, as safety net programs are not yet universal, for many older people, income security and access to health care remain concerns.

The Informal Sector Includes a High Proportion of the Labor Force in Mexico

As of 2005, the informal sector in Mexico represented approximately 58 percent of the labor force. Because these individuals typically lack financial security and health care coverage in retirement, they often continue working in old age in order to support themselves and their families, thereby contributing to Mexico's high effective retirement age.

Many Older Mexicans Work After Traditional Retirement Age

Among OECD countries, Mexico stands out for having the highest average effective retirement age for men, at 72.2, and the second-highest for women, at 69.5. The average OECD official retirement age in 2010 was 63.1 years for women and 64.4 years for men. Retirement patterns in Mexico reveal that about 46 percent of men and 15 percent of women aged 65 and older remain in the labor force.

In 2000, one in four men in Mexico still worked at age 80. Women are less likely to participate in the labor market and are also less likely to work outside of the home in old age. They are, however, more likely than men to be recipients of their children's financial assistance, including remittances.

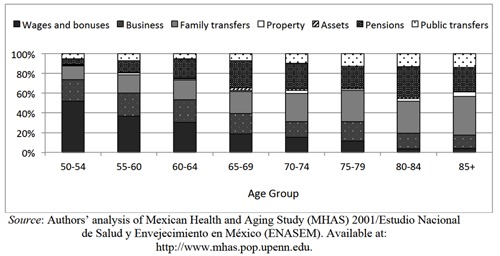

Informal Sources of Income Are Important to Older Mexicans

Figure 2 shows the sources of income for older Mexicans. Family transfers and pensions (including public and private pensions) gain in importance as individuals get older. From age 70 on, family transfers, including remittances, are the most important component of income. Public transfers, including noncontributory pensions, play a small role and become increasingly important at older ages. Above age 85, wages and business revenue still make up more than 10 percent of income. Overall, the dominant picture emerging from the data is one where pensions play a modest role and informal mechanisms such as family transfers or work at advanced ages provide most of the income of older people.

Figure 2.

Sources of Income by Age Bracket, 2001

Remittances from Children Working Abroad Are a Major Source of Income for Many

Family transfers, especially remittances from children working in the United States, play a large role in supporting Mexico's older population. According to MHAS, among older adults who receive help from their children, 16.2 percent are remittance recipients. Remittances represent almost 60 percent of gross income among recipients.

Individuals' Health in Later Life Depends on Many Factors

The physical well-being of an individual is connected to his or her socioeconomic status (SES), gender, marital status, and employment. These factors also play a role in what kinds of health services are sought and what is available.

The geographic distribution of poverty in Mexico is associated with indicators of poor health status. Ethnic groups that generally have low levels of SES, particularly indigenous communities, also face health challenges that differ from those of groups with higher SES. Previous studies have found that education level is one of the few factors that is consistently associated with good health in middle age and beyond.

In Mexico, economic conditions for a high proportion of individuals deteriorate sharply after reaching retirement and continue to worsen as they grow older. Older people are thus especially vulnerable to health risks associated with poverty and a low quality of life.

Older people with health insurance are more likely to find their health to be excellent, very good, or good (43.8 percent among the insured vs. 32.8 percent among the uninsured) and are less prone to having strokes (2.2 vs. 3.0 percent), arthritis (17.2 vs. 23.1 percent), and limitations with activities of daily living (4.9 vs. 9.4 percent). However, they are more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes (17.8 vs. 13.0 percent) and to be obese (20.0 vs. 12.5 percent). About 37 percent of older Mexicans report having hypertension.

Long-term return migrants (i.e., those who stayed in the United States more than a year and eventually returned to Mexico) have higher mean and median household income and net worth than do shorter-term return migrants and nonmigrants. Male short-term return migrants and nonmigrants have a higher coverage of health insurance from social security institutions than long-term return migrants.

Health Care Expenditures Vary by Age

Individuals' medical expenses, particularly when they approach old age, consist mainly of physician visits and outpatient procedures. Those at the low end of the income distribution tend to spend less on services than the richest individuals, although these costs do not show a clear gradient with income. Being a social security beneficiary is associated with an average reduction of out-of-pocket expenses of 860 pesos (USD 121 at 2005 purchasing power parity, or PPP) annually, due to access to social security-provided health care.* Some of these out-of-pocket costs are paid out of family transfers and remittances.

Some Policy Options for Increasing Old-Age Income Security and Health Status in Mexico

The observations above suggest a number of policy directions that may be explored to improve income security and health status in old age in Mexico:

Extending the safety net for older people by providing basic noncontributory pensions. It is important to develop appropriate means-testing mechanisms to target older people in poverty. Traditional means-testing mechanisms for individuals of working age with a regular income would not apply for many older people with sporadic income who often rely on family transfers.

Promoting saving for retirement by extending the coverage of funded social security programs and by promoting private instruments for saving, making enrollment in the social security system (pensions and health care) mandatory for the self-employed, improving the enforcement of social security contributions for workers in registered firms, and developing new saving products.

Improving health status and extending health care coverage through increased social security coverage.

Integrating return migrants into the social security system by allowing them to contribute to Mexican social security while abroad and through portability of benefits.

Increasing financial literacy to help Mexicans plan for retirement.

Establishing a national agency to oversee the fragmented social security system in Mexico and to improve the effectiveness of policy making in this area.

The demographic transition in Mexico combined with the lack of formal sources of income in retirement puts many older people at risk of financial insecurity. The information in this article and the proposed policy recommendations for further research are intended to broaden the portfolio of options for older Mexicans.

Notes

The PPP exchange rate from Mexican pesos to U.S. dollars (USD) in 2005 was 7.126862 (from OECD Stat Extracts).