Short abstract

This article presents the results of an evaluation of health care performance measures, describes how performance measures are being used, summarizes key barriers and facilitators to their use, and identifies opportunities for easing that use.

Abstract

The National Quality Forum (NQF), a private, nonprofit membership organization committed to improving health care quality performance measurement and reporting, was awarded a contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish a portfolio of quality and efficiency measures. The portfolio of measures would allow the federal government to examine how and whether health care spending is achieving the best results for patients and taxpayers. As part of the scope of work under the HHS contract, NQF was required to conduct an independent evaluation of the uses of NQF-endorsed measures for the purposes of accountability (e.g., public reporting, payment, accreditation, certification) and quality improvement. In September 2010, NQF entered into a contract with the RAND Corporation for RAND to serve as the independent evaluator. This article presents the results of the evaluation study. It describes how performance measures are being used by a wide array of organizations and the types of measures being used for different purposes, summarizes key barriers and facilitators to the use of measures, and identifies opportunities for easing the use of performance measures moving forward.

Over the past two decades, a wide array of standardized health-care performance measures have been developed, and a large number of these have been endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF). During this period, there was also substantial growth in the number of entities using health-care performance measures for a host of purposes. Quality and efficiency measures are now embedded throughout the U.S. health-care system, as demonstrated by their widespread use for accountability; accreditation, certification, credentialing, and licensure; public reporting; pay for reporting (P4R); pay for performance (P4P) and performance-based contracting; tiering and construction of narrow provider networks; quality improvement (QI); and public recognition. Although there has been significant growth in the use of performance measures (Madison, 2009; National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2010), there has been no systematic attempt to catalog the various ways in which measures are being used and what opportunities exist for enhancing the end users' ability to use performance measures to achieve their desired objectives.

Under requirements in the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (Pub. L. 110–275, 2008), the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) contracted with NQF to carry out a set of activities related to the establishment of a portfolio of quality and efficiency measures that would enable the federal government to examine how and whether health-care spending is achieving the best results for patients and taxpayers. One component of this work was to engage an independent third party to evaluate the uses of performance measures for purposes of accountability and QI. A recently completed NQF study highlighted the need for understanding how measures are being used (Booz Allen Hamilton, 2010).

NQF engaged the RAND Corporation to conduct an independent examination of the use of performance measures, with particular interest in the use of NQF-endorsed measures. The goal was to better understand

the current state of performance measure use across the broad spectrum of end-user types

areas in which gaps in measures exist that hinder the end users' ability to apply measures to support the achievement of their desired goals

how the larger measurement enterprise (i.e., measure developers, measure endorsers, foundations and government agencies that support measure development and implementation) might better support the use of performance measures.

The RAND team reviewed the peer-reviewed published literature and documents drawn from the non–peer-reviewed (i.e., gray) literature of the past five years as part of this project and found no existing study that cataloged all uses or types of measures within each use. The absence of a comprehensive assessment underscores the importance of this project.

Study Questions and Approach

The overarching questions addressed in this study were as follows:

How are performance measures being used in practice?

What factors are influencing measure use, particularly endorsed measures?

What types of system changes have occurred as a result of measure use?

What improvement areas could facilitate the use of standardized endorsed performance measures by various end users?

Within the six-month time frame and scope of the project, the study team could not conduct an exhaustive review of the use of performance measures for various purposes. Instead, the project focused on conducting a scan of the current measure-use landscape to address the study questions.

The study design consisted of two data-collection methods: (1) interviews with end-user key informants (n = 30 end-user organizations) and (2) review of publicly available documents and materials from websites (n = 70 end-user organizations, of which 30 participated in the key-informant interviews). For both data-collection methods, we selected a purposive sample of organizations from 11 different categories of end-user organizations or entities (e.g., consumers, purchasers, community collaboratives) and end uses. The missions of the end users varied and included organizations focused on improving quality, creating information to help consumers select providers, working to assess the competencies of providers and health plans to deliver high-quality care, structuring incentives to drive improvements in care, and promoting competition on price and quality. We interviewed the executive director, president, or chief executive officer or the lead person responsible for quality-measurement activities within the organization.

We classified the use of performance measures into four broad categories of measure end use (i.e., the purpose for which measurement is used):

QI

public reporting

accreditation, certification, credentialing, and licensure

payment applications (e.g., financial incentives, tiering, narrow networks).

Organizations could be recorded as using measures for up to a maximum of four of these different end uses. We also recorded end uses that fell outside these four categories.

We focused our review on the primary end user of performance measures. The primary end user is defined as any organization that is directly engaged in the implementation of health-care quality or efficiency measures to assess the performance of providers of health care (i.e., hospitals, physicians, nursing homes, health plans). The primary end user is the organization that gathers the data; gains access to data for use in constructing measures or, in some cases, uses preexisting measures; uses data to construct measures; computes the performance score of providers; and makes use of the resulting performance information.

Primary end users make performance information available with the expectation that others (i.e., providers, consumers) will use the performance measures to drive system changes, make behavior changes, or inform decisions. The others we define as secondary end users of the information. An example of the secondary use of performance measures would be a medical group changing its behavior in response to receiving performance scores from a community collaborative or consumers using comparative performance information on health plans to select a plan. The scope of this contract did not permit the exploration of secondary uses, although this would be an important area to address in a future impact study.

Key Findings

Use of Performance Measures

According to our review of documents from end users, many organizations are using measures for multiple purposes, such as public reporting and P4P. There were a total of 127 uses documented for the 70 organizations included in the sample. Forty of the 70 organizations reported more than one use of performance measures. During the key-informant interviews, several end users reported other uses of performance measures beyond the four broad categories of focus for this study, including evaluation (e.g., evaluating the impact of an intervention) and compliance monitoring of health plan contracts.

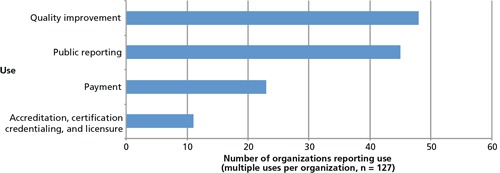

Public reporting (64 percent [45 of 70]) and QI (69 percent [48 of 70]) were the most commonly reported uses among the four end uses (see Figure 1). In contrast, uses for payment (33 percent [23 of 70]) and accreditation, certification, credentialing, or licensure (16 percent [11 of 70]) were reported less often.

-

End users reported using measures drawn from seven core measurement domains: structure, process, outcome, access, safety, costs, and patient experience.* At this juncture, process measures are the most common type of measure being used (83 percent of measure uses report using process-of-care measures). The use of different types of measures varies by type of end use and the setting of care in which measures are being applied:

- Structural measures are most likely to be used by those doing accreditation, certification, credentialing, or licensure (46 percent [five of 11] of these uses); cost measures are most likely to be used by those doing public reporting and P4P (49 percent [22 of 45] and 52 percent [12 of 23] of these uses, respectively); and patient-experience measures are most likely to be used by those doing public reporting (76 percent [34 of 45] of this use).

- Access measures are the least commonly used type of measure overall, with 24 percent (31 of 127) of all uses reporting inclusion of this measurement domain. In our sample of organizations, access measures are reported being used in 18 percent (two of 11) of accreditation, certification, credentialing, or licensure uses; 13 percent (three of 23) of payment uses; 35 percent (16 of 45) of public reporting uses; and 21 percent (ten of 48) of QI uses.

- In the inpatient setting, the domains most commonly measured are process of care (93 percent), outcomes (73 percent), safety (69 percent), and patient experience (64 percent), while, in the ambulatory setting, the domains most commonly measured are process of care (90 percent), outcomes (68 percent), cost (53 percent) and patient experience (56 percent).

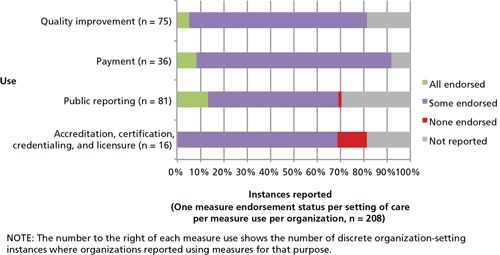

Across 208 uses of measures in various settings of care among the 70 end-user organizations, 69 percent (143 of 208 setting/use pairs) of the uses included a combination of endorsed and nonendorsed measures, 9 percent included only endorsed measures, and 1 percent do not include any endorsed measures (Figure 2). Due to incomplete documentation, we were unable to determine NQF endorsement status for 21 percent (44 of 208) of the setting/use pairs.

Claims and administrative data are the most common data source used to construct measures (76 percent [97 of 127] total measure uses reported using administrative data sources), followed by patient survey (56 percent [71 of 127] of uses), self-reported data (38 percent [48 of 127] of uses), and medical records (35 percent [45 of 127] of uses).** Each of these data sources was utilized within each of the four broad categories of end use.

Figure 1.

Frequency of Measure Uses (n = 70 organizations)

Figure 2.

Use of National Quality Forum–Endorsed Measures in Measurement Instances (n = 70 organizations)

Factors Influencing Measure Use

The following factors affect measure use:

A combination of internal and external factors is driving the use of performance measures. For example, federal agencies are responding to legislative requirements related to quality-based payments and public reporting contained in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Pub. L. 111–148, 2010), and some states face legislative mandates to do public reporting. Some organizations are responding to local health issues, such as obesity, while others indicated they are using measures to operationalize their mission.

The single most important factor cited as either facilitating or impeding the use of measures was the availability of data to construct performance measures.

Factors facilitating the use of measures include a strong data infrastructure; provider trust in the measurement process and the evidence base of the measures; alignment of measures among reporting initiatives to minimize reporting burden; relevance to members, consumers, and providers; and provider training on how to extract the data. Additionally, it was noted that NQF endorsement or widespread use of a measure enhanced provider buy-in.

-

In “high-stakes” accountability applications (Safran et al., 2006), such as payment and public reporting, end users reported a preference for using endorsed measures that were evidence-based and validated (among the 30 organizations we interviewed). However, end users indicated a willingness to use nonendorsed measures to address a priority need.

- The use of nonendorsed measures reflects a perceived need to modify NQF-endorsed measures to adapt to local use (e.g., relax exclusion criteria to increase the number of people included in the measure denominator) or a need to measure an area that is not yet represented in the NQF group of measures (e.g., resource use).

- Other criteria commonly applied in the selection of measures include relevance to members, consumers, providers, or payers; feasibility of data collection; and scientific acceptability.

Factors impeding the use of measures include lack of measure prioritization; “measure fatigue” in addressing national, state, and regional requirements (i.e., lack of alignment); the cost of measurement; the lack of timely data; and the challenge of reliably measuring the performance of individual physicians and small physician groups given small denominator sizes for many measures.

Anticipated changes to the use of measures moving forward include increased capacity for broader and different types of measures with electronic health records (EHRs), registries and other health information technology (HIT) capabilities; newer types of measures (e.g., longitudinal outcomes, functional status, cost and resource use); new settings (e.g., nursing homes, home health); new populations (e.g., patients who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, referred to as “dual eligible”); and more-widespread use in emerging payment applications (e.g., bundled payments, medical homes, accountable care organizations [ACOs]).

System Changes Resulting from Measure Use

The following system changes resulting from measure use were reported:

Among those we interviewed, few reported they had performed formal studies to document results, particularly in the realm of return on investment. Several organizations noted that they were just beginning the process to evaluate the impact of their measurement activities. Formal evaluation is hindered by a lack of comparison groups (i.e., control groups, pre/post data), resources to support evaluation, and, in some cases, evaluation “know-how” on the part of the end user.

Some anecdotal examples were provided of system changes resulting from organizations' use of measures. End users cited improvements in generic prescribing rates, premium savings accrued from implementation of tiered health plan products, performance improvement on selected clinical measures, improvement in patient experience scores, and physician practice changes resulting from QI initiatives.

Several organizations interviewed reported that performance measures had had little effect on consumer behavior as a result of publicly reporting performance, although they did observe that public reporting has influenced provider behavior.

Advice to Improve the Uptake of Standardized Measures

Our interviews yielded the following recommendations for improving the uptake of standardized measures:

A range of measure gaps and opportunity areas for new measures were identified, including coordination of care, outcomes, patient safety (inpatient and ambulatory), measures of longitudinal change in outcomes, cost and resource use, population health, nursing-sensitive care, access and affordability, measures that consider a patient's risk profile, composite measures, and measures that address specific conditions (e.g., maternity, mental health, end-of-life care) and settings and populations (e.g., home health, dually eligible individuals).

There were recommendations for adding new measures that address specialty care; however, some respondents commented that resources should not be used to develop unique measures for every specialty. Consideration should be given to developing crosscutting measures that address the care delivered by multiple clinical specialties.

The expression of need for more measures was counterbalanced by comments regarding the need for better alignment and prioritization of existing measures to help in selection and use of measures. One interviewee commented, “It is less a demand for more measures and more a problem that the extant measures are very distracting and not aligned.” Interviewees stated a need to ease their selection of measures by “weeding out” or rationalizing endorsed measures or selecting the “best in class” when there are very similar endorsed measures, as well as guidance on choosing the most important and effective measures to drive change.

-

There were specific recommendations from end users related to opportunities for NQF process improvements:

- End users expressed a desire for improvements to the NQF website to enhance the search capability, obtain full measure specifications, and access more information about where and how measures are being used.

- End users also suggested that NQF work to advance the conversation about the appropriate use of composite measures, provide a clearinghouse for QI measures, provide outreach and education to stakeholders in their communities (particularly physicians and other health-care providers), publicize upcoming calls for measures and the review calendar so that organizations could coordinate their review processes with NQF's, and provide more advanced notice of upcoming calls for measures so that developers have more time to test measures prior to submission.

Future Opportunities to Support the Use of Measures

As the measurement development, endorsement, and application communities reflect on the results of this study, we note that several issues emerged that represent opportunities and potential areas of focus moving forward to help facilitate the use of measures:

Establish priorities for where end users should focus their attention and resources. Although NQF has a large number of endorsed measures, the sheer number is daunting to end users, and many measures are viewed as irrelevant or low impact. Given the limited resources and attention that end users can devote to measurement, they need guidance on defining a more limited set of high-value, high-leverage measures to which they should devote resources that will lead to real improvements in outcomes or efficiency (fewer resources spent without reductions in quality). Outcome measures were seen as high-value measures that should be prioritized.

Align measures. Among those who are the focus of measurement (i.e., providers), there is an important need to help reduce the burden of reporting to a wide array of entities by ensuring that the measures used by the entities are aligned. Currently, reporting efforts among the various stakeholders operate independently, are frequently not aligned, and lead to increased data collection, analysis, and reporting burdens for providers. Establishing measure priorities can create an opportunity for better alignment among the various parties that impose reporting requirements. Cataloging the specific types of measures being used for each end use could help inform efforts to align measures.

Develop new measures for new measure uses. The measure-use landscape continues to evolve, particularly in response to health system reform efforts. End users are preparing for new measure-use opportunities and the need for different types of measures, particularly in the payment use area (e.g., ACOs, value-based purchasing [VBP] applications, episode-of-care and bundled payment models). Additionally, there is a desire for crosscutting measures that apply to all providers both to broaden the group of providers that can be assessed and to minimize the number of measures that have to be constructed. Additionally, end users expressed strong interest in new measures that would track the functioning of the patient and how functioning and other key outcome markers change longitudinally (i.e., improvement measures).

Build support for the use of measures. The criteria that are most salient to end users in choosing measures for use are (1) the measure is relevant to providers who must act on them, as well as consumers and payers; (2) the data needed to construct the measure are feasible to collect; and (3) the measure has a scientific evidence base to ensure its acceptability to providers.

Measure construction requirements in the evolving data landscape. At present, end users are relying heavily on claims and administrative data and patient surveys and are not yet able to systematically and efficiently capture information that will enable the construction of intermediate and longitudinal outcomes. At a minimum, a limited, prioritized set of measures should be the focus of front-end planning to influence the data architecture (e.g., data fields and not free text) of EHRs and other HIT to support the construction of measures. The development of better data sources, such as what is envisioned through HIT sources, has the potential to enable better measurement and use of measures.

Conduct a systematic review of the literature to fully catalog measure use. The scope of this project did not permit a full review of the literature to examine uses of measures for a variety of purposes and to explore the secondary use of measures (e.g., by providers who are exposed to performance results in public report cards, consumers who are shown performance report cards). A thorough review of the literature would extend the work in this study and provide for a deeper understanding of uses and issues related to use of measures.

Formally assess the system-change results from the use of measures. Although end users cite anecdotal examples of the benefits that have accrued from use of performance measures, it is unclear how many of these benefits have been formally evaluated and documented. This underscores the need for a future study that would systematically attempt to quantify the impacts that have resulted from measure use, given the substantial investment that has been made to use measures to drive system change.

Create support tools to help end users. End users want access to full measure specifications, more information about where and how measures are being used, and an ability to more easily search the measures contained in the NQF-endorsed set of measures. Improved search functions and new tools could facilitate end users' ability to use measures. End users also see value in increased outreach and education to stakeholders in their communities (particularly physicians and other health-care providers) about the validity of the measures and why measurement is important as a means of better engaging them in performance improvement.

Notes

We assessed measure domains and endorsement status for each setting of care per measure use per organization.

We assessed data sources used for each measure use per organization.

Reference

- Allen Hamilton Booz, Synthesis of Evidence Related to 20 High Priority Conditions and Environmental Scan of Performance Measures: Final Report, Washington, D.C.: National Quality Forum, January 13, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, Kristin, “The Law and Policy of Health Care Quality Reporting,” Campbell Law Review, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2009, pp. 215–256. [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance, The State of Health Care Quality: Reform, the Quality Agenda and Resource Use, Washington, D.C., 2010. As of October 24, 2011: http://www.ncqa.org/portals/0/state%20of%20health%20care/2010/sohc%202010%20-%20full2.pdf

- Public Law 110–275, Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008, July 15, 2008. As of October 24, 2011: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ275/content-detail.html

- Public Law 111–148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, March 23, 2010. As of October 24, 2011: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/content-detail.html

- Safran, Dana Gelb, Karp Melinda, Coltin Kathryn, Chang Hong, Li Angela, Ogren John, andRogers William H., “Measuring Patients' Experiences with Individual Primary Care Physicians: Results of a Statewide Demonstration Project,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 21, No. 1, January 2006, pp. 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]