Short abstract

Provides detail from an evaluation of 211 programs currently sponsored or funded by the Department of Defense to address psychological health and traumatic brain injury, along with recommendations to maximize program effectiveness.

Abstract

Over the last decade, U.S. military forces have been engaged in extended conflicts that are characterized by increased operational tempo, most notably in Iraq and Afghanistan. While most military personnel cope well across the deployment cycle, many will experience difficulties handling stress at some point; will face psychological health challenges, such as post-traumatic stress disorder or major depression; or will be affected by the short- and long-term psychological and cognitive consequences of a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Over the past several years, the Department of Defense (DoD) has implemented numerous programs that address various components of psychological health along the resilience, prevention, and treatment continuum and focus on a variety of clinical and nonclinical concerns. This article provides detail from an evaluation of 211 programs currently sponsored or funded by DoD to address psychological health and TBI, along with descriptions of how programs relate to other available resources and care settings. It also provides recommendations for clarifying the role of programs, examining gaps in routine service delivery that could be filled by programs, and reducing implementation barriers. Barriers include inadequate funding and resources, concerns about the stigma associated with receiving psychological health services, and inability to have servicemembers spend adequate time in programs. The authors found that there is significant duplication of effort, both within and across branches of service. As each program develops its methods independently, it is difficult to determine which approaches work and which are ineffective. Recommendations include strategic planning, centralized coordination, and information-sharing across branches of service, combined with rigorous evaluation. Programs should be evaluated and tracked in a database, and evidence-based interventions should be used to support program efforts.

Between 2001 and late 2010, over 2.2 million servicemembers were deployed in support of military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Despite the recent drawdown of troops in Iraq, the high operational tempo of the past decade, longer deployments, and frequent redeployments have resulted in significant mental health problems among servicemembers. While most military personnel cope well under these difficult circumstances, many have experienced and will continue to experience difficulties related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD, an anxiety disorder that can develop after direct or indirect exposure to an event or ordeal in which grave physical harm occurred or was threatened) or major depression. Others live with the short- and long-term psychological and cognitive consequences of traumatic brain injury (TBI), an injury that has become increasingly common with the growing use of improvised explosive devices on the battlefield. These issues may also have consequences for military families, as struggles related to PTSD, depression, or TBI may affect marriage and intimate relationships, the well-being of spouses and partners, parenting practices, and children's well-being.

A variety of factors—including increased news coverage regarding the psychological and cognitive consequences of deployment, recommendations resulting from the work of highly visible advisory committees, the expansion of numbers of mental health providers available in military clinical care settings, and the establishment of the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE)—have created significant motivation and momentum for developing programs to support servicemembers and their families. Despite the proliferation of programs and related efforts, an ongoing challenge for the Department of Defense (DoD) is to identify and characterize the scope, nature, and effectiveness of these various and ever-evolving activities. Prior to this study, there has been no full accounting of what programs exist and how these programs complement “traditional” service provision and routine care.

Focus of This Study

The goal of this study is to provide a “snapshot” of all programs currently sponsored or funded by DoD that address psychological health and TBI. In this article, we characterize these programs; identify barriers to implementing them fully and maximizing their effectiveness; and provide recommendations for clarifying the role of programs, examining gaps in routine service delivery that could be filled by programs, and reducing barriers that programs face.

We used a multifaceted approach to identify programs for inclusion in this study. Initially, we sought to identify as many potential programs as possible (e.g., through web and media searches; review of program materials and public domain documents; and consultations with military personnel, nonprofit organizations, and subject matter experts). Then we obtained information about the potential programs through interviews with program representatives or, when program representatives were not available, through publicly available documentation. We then applied a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine which entities were programs. Our efforts focus on programs that were active during our field period, which began in December 2009 and ended in August 2010. Programs identified after this report was written will be added to the Innovative Practices for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury online database on the RAND website, located at http://www.rand.org/multi/military/innovative-practices.html, that houses information about each program.

What Is a Program?

In this study, the term program is used to describe entities that provide active services, interventions, or other interactive efforts to support psychological health, as well as care for servicemembers (and their families) who are experiencing such problems as PTSD, anxiety, depression, and TBI. Programs are distinct from clinical care services (e.g., mental health services, clinical services for physical health problems) and non–clinical care services (e.g., services provided in chaplaincy or community and family support departments, including other services unrelated to psychological health and/or TBI). The programs that are discussed in this study may be provided within the same facility or organizational structure that provides these other types of services. Programs are also distinct from resources, a term that here refers to one-way, passive transmission of information (e.g., a directory that lists services available at an installation).* Programs to address psychological health and TBI rely on a strong and growing research base to identify new treatments and best practices. While research projects are explicitly beyond the scope of this study, some research projects include an intervention component that could be classified as a type of program.

In the study, we identified a total of 211 programs. Identifying these programs was a complex task, and one key finding from our work is that no single source within DoD or any of the branches of service maintains a complete listing of programs, tracks the development of new programs, or has appropriate resources in place to direct servicemembers and their families to the full array of programs that best meet their needs. Programs may be initiated in a number of different ways, including centrally by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), by a branch of service, or based on the interests of a small number of individuals at a single installation, further complicating efforts to identify and track programs over time.

A Typology of Program Activities

To better understand the types of services provided by the programs, we grouped programs based on their mission, goals, and activities to develop a typology that can be used to describe what programs do. As a result of these efforts, we identified three broad areas along the prevention, identification, and treatment continuum (Table 1), each of which is further categorized by two or more specific themes. Together, these encompass 23 key activities in which programs engage. In addition, we describe three more specific areas of focus (Table 2) that are common to some of the programs included in this study, with eight common key activities.** The categories in this typology are not mutually exclusive, and many programs are described by more than one category.

Table 1.

Typology of Program Activities: Prevention, Identification, and Care for Psychological Health Problems and Traumatic Brain Injury

| Area | Theme | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Preventing problems | Reducing the incidence of psychological health problems and TBI |

Improving resilience and the ability to handle stress among members of the military community Promoting readiness, increasing combat and operational stress control, and preparing for the psychological health consequences of combat |

| Employing public health approaches |

Preventing incidents of domestic violence Preventing incidents of sexual assault Reducing the risk of substance abuse Preventing suicide |

|

| Identifying individuals in need and connecting them to care | Providing information, connecting individuals to care, and encouraging help-seeking |

Operating a telephone hotline that provides immediate access to counselors and other resources Serving as an information hub that provides referrals to care Reducing barriers associated with seeking help for mental health conditions or TBI and/or providing education regarding specific conditions |

| Identifying individuals with mental health concerns or TBI |

Conducting routine screening for mental health problems or TBI in the absence of reported symptoms Increasing the capacity for early identification of mental health problems outside the health care system, with the goal of referring individuals to care when needed |

|

| Caring for servicemembers and families in need | Providing or improving clinical services |

Providing comprehensive care for severe or persistent problems among wounded, ill, and injured servicemembers Improving transitions between care settings and providers, improving coordination and continuity of care, or providing case management Providing clinical services for mental health concerns, TBI, or other clinical concerns |

| Offering mental health services in nontraditional locations to expand access to care |

Embedding mental health providers in primary care or other non–behavioral health clinical settings or other initiatives to improve treatment for mental health conditions in primary care settings Embedding mental health providers within military units |

|

| Nonclinical activities that provide support |

Training servicemembers to provide peer-to-peer support for improving psychological health Offering complementary and alternative treatment services to help address the consequences of mental health concerns and TBI Providing spiritual support |

|

| Responding to incidents of concern |

Responding to incidents of domestic violence Responding to incidents of sexual assault Responding to substance abuse problems Engaging in post-suicide response |

Table 2.

Typology of Program Activities: Specific Areas of Program Focus

| Theme | Activities |

|---|---|

| Providing training, education, or support for specific populations |

Providing training, education, or support for health care providers, chaplains, or educators Providing training, education, or support for military leaders, including officers and noncommissioned officers Providing training, education, or support for servicemembers' families Programs that promote psychological health for National Guard, Reserve, or Coast Guard servicemembers |

| Providing support during times of military transition |

Providing support for servicemembers and their families during transitions between deployment phases Providing support for servicemembers as they transition to civilian life |

| Internet-based interventions and the use of new technologies |

Internet-based education or delivery of interventions Application of new technologies |

Program Characteristics

We also characterized the programs according to a variety of topics, including branch of service, targeted participants, approach, scale, and clinical and nonclinical issues addressed, among others.

Branch of Service and Deployment Phase

Each branch of service has a unique set of needs for addressing psychological health services and TBI among its servicemembers. Variation in need is related to the relative size of each service, its operational tempo, the types of activities in which its servicemembers engage, and other services that may be available to support servicemembers and their families. Most programs, regardless of branch of service, focus their efforts on uniformed servicemembers, with some programs offering services to family members and civilian employees. Within each branch of service, more programs are typically offered for active-duty servicemembers than for those in the National Guard or Reserve components. Although some programs focus on a single deployment phase, the large majority of programs address multiple deployment phases or are not related to a deployment phase.

Clinical and Nonclinical Issues Addressed by the Programs

Because multiple mental health issues may occur simultaneously and because TBI is frequently associated with accompanying mental health issues, programs typically address more than one clinical issue. In general, though, fewer programs focus on TBI than on issues associated with psychological health—including depression, PTSD, substance use, suicide prevention, and general psychological health. In terms of nonclinical issues addressed, many programs focus on issues related to families and/or children, resilience, stress reduction, deployment, or postdeployment and reintegration.

Evidence Base

Based on the information reported to us during our interviews, DoD-wide and Army programs are more likely to report that their interventions are evidence based than programs serving the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. We did not assess the strength of the evidence base employed, so it remains possible that these differences reflect varying perceptions of the individuals interviewed. It is also possible that there is differential availability of an adequate evidence base for the particular programs of interest to each of the services. Comparatively few programs—between one-tenth and one-third of programs targeting any branch of service—have had an outcome evaluation in the past 12 months. While more than three-quarters of all programs that we include in this report collect some process data (such as numbers of program participants or their satisfaction with the program), many fewer collect data on the outcomes of the services they provide.

Barriers to Maximizing the Effectiveness of Programs

Our analysis identified a number of potential barriers that must be addressed in order to maximize program effectiveness.

Information Is Highly Decentralized

During our interviews, a number of program representatives noted that they did not know whether others in the DoD community had similar programs or materials they could borrow or learn from, what approaches other programs had used, and whether other programs had been successful in the past. In part as a result of this lack of sharing of knowledge, programs proliferate without utilizing a centralized evidence base or source for materials. This can lead to significant inefficiencies, such as multiple programs developing teaching points and training materials on the same topic.

Programs Are Developed in Isolation from the Existing Care System

Some programs are designed to encourage the early identification of mental health concerns and to provide appropriate referrals to clinical care where needed. However, relatively few programs are established in partnership with or sustain formal relationships with existing clinical or supportive counseling services, except where such programs are embedded as an inherent part of the existing care system. This lack of linkage and partnership can leave programs without a consistent course of action when follow-up care is needed.

Programs Face Common Barriers

Programs also face many barriers in providing services. The most common barriers mentioned by our interviewees included inadequate funding, resources, or staff capacity; potential concerns about the stigma associated with receiving mental health services, including fear of career repercussions; and inability to have servicemembers spend adequate amounts of time with the program staff and/or materials because of other obligations on the part of participants or providers. Other barriers were mentioned less frequently, including program logistics (such as hours of operation, transportation, and administrative barriers to participation); a lack of awareness among potential participants about the program and/or its services; and the lack of full support from military leadership. Several programs also reported concerns regarding a lack of continuity of care when servicemembers are deployed or undergo a permanent change of station.

Evaluation Is a Challenge

Programs are evaluated infrequently—fewer than one-third of programs in any branch of service reported having had an outcome evaluation in the past 12 months. At the same time, for those programs conducting an evaluation, the rigor of the evaluation may vary in terms of whether it was conducted by an independent party or by program staff, whether it had a control group, whether it examined both processes (implementation efforts) and outcomes, and the appropriateness of the metrics used.

Recommendations

Based on our interviews with program representatives and the process of identifying these programs, we identified several high-level priorities for DoD:

Take advantage of programs' unique capacity for supporting prevention, resilience, early identification of symptoms, and help-seeking to meet the psychological health and TBI needs of servicemembers and their families.

Establish clear and strategic relationships between programs and existing mental health and TBI care delivery systems.

Examine existing gaps in routine service delivery that could be filled by programs.

Reduce barriers faced by programs.

Evaluate and track new and existing programs, and use evidence-based interventions to support program efforts.

Take Advantage of Programs' Unique Capacity for Supporting Prevention, Resilience, Early Identification of Symptoms, and Help-Seeking to Meet the Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Needs of Servicemembers and Their Families

Our work finds a lack of clarity regarding the role of programs and the unique contribution that they can make to addressing psychological health and TBI among members of the military community. This section offers recommendations regarding how to capitalize on the strengths that programs often possess in order to address these issues.

Recommendation 1.1: Develop programs' capacity for early identification, promotion of help-seeking, and referrals to appropriate resources for members of the military community with mental health concerns. Programs can potentially play a unique role in training and education to support early identification of concerns and symptoms, encouraging individuals to seek help, and identifying resources to provide such assistance.

Recommendation 1.2: Programs bring particular strength in focusing on prevention and resilience; this capacity should be further developed. Programs offer opportunities to build skills in these areas among servicemembers and their families. The growth of such programs should emphasize the adoption of evidence-based approaches. At the same time, careful attention should be paid to the messages developed as part of these programs. Overemphasis on resilience may have the unintended consequence of increasing stigma, since individuals with symptoms of psychological health problems may feel that help-seeking is a sign that they are not resilient.

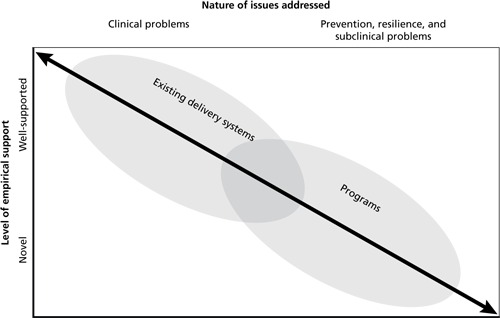

Recommendation 1.3: Programs should serve as testbeds for piloting new and innovative approaches to psychological health and TBI care. Figure 1 presents an overview of the ideal characteristics of services provided by programs and by the existing delivery system, including clinical care and supportive counseling services. It illustrates where the existing delivery system and programs would each ideally place their primary emphasis. Under this framework, the majority of care provided in existing delivery systems should consist of treatment approaches that are supported by an empirical evidence base, although care in these settings may also rely in part on treatment approaches that have mixed or less empirical support. Ideally, novel or unproven treatment approaches would be avoided in this setting, except when explicitly part of a clinical trial or other research project with appropriate protections in place for servicemembers and their families who receive such treatment. Programs offer opportunities to test new and innovative approaches for addressing psychological health and TBI and can provide a mechanism for building the evidence base for both clinical care and for nonclinical approaches. With appropriate research and evaluation to demonstrate program effectiveness, a subset of programs may be scaled up for widespread implementation, or program approaches might become part of routine care, when appropriate.

Figure 1.

Ideal Characteristics of Services Provided by Programs and the Existing Delivery System

Establish Clear and Strategic Relationships Between Programs and Existing Mental Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Care Delivery Systems

Reliable and accessible lines of communication and established referral processes between programs and existing clinical care systems are essential to ensure that programs can meet their potential to serve as a means of early identification of clinical and subclinical symptoms, to function as testbeds for new and innovative approaches to care, and to address subclinical cases and enable the health care system to focus on those servicemembers with more-severe concerns.

Recommendation 2.1: Programs should complement or supplement existing services. Programs may do so by focusing on subclinical psychological needs, which can divert some of the burden on the clinical care system and supportive counseling services; by focusing on prevention, resilience, and early identification of problems; by embedding mental health providers in nontraditional locations, such as within military units or in primary care settings; or by providing services in coordination with the clinical care system. While there are existing programs that address subclinical psychological needs and those that embed mental health providers in nontraditional settings, this recommendation is intended to suggest the need for increasing and/or expanding those types of programs.

Recommendation 2.2: Ensure that systems exist to support appropriate handoffs between programs and other settings and that transitions in care are appropriately coordinated. Ensuring appropriate referrals and transitions between providers and care settings is essential for ensuring that servicemembers' and family members' needs for care are met, that their care is continuous and coordinated, and that they transition safely between care providers. This focus on continuity of care is particularly important for programs that are focused on early identification of problems and those that provide limited treatment.

Recommendation 2.3: Track referrals from programs to existing clinical care systems on a continual basis, including the volume of referrals and rates of follow-up on referrals received. Since many programs are designed to help servicemembers and their families identify potential mental health problems in their early phases, it is important to ensure that appropriate resources and follow-up services are available when needed and to understand the extent to which individuals follow through on referrals that are made. For individuals to successfully access follow-up care when referred from programs, there needs to be adequate capacity to provide services in clinical and supportive counseling settings.

Examine Existing Gaps in Routine Service Delivery That Could Be Filled by Programs

Ideally, a report such as this would describe specific gaps in services provided by programs, highlighting content areas, specific populations, and geographic regions where new program development would offer significant benefit. In order to do so, however, we would need information that is not currently available, since few programs begin with a formal needs assessment or an estimation of the numbers of servicemembers and family members in need of assistance. Our recommendations therefore highlight the prerequisite for conducting such a gap analysis: a comprehensive needs assessment.

Recommendation 3.1: Conduct a comprehensive needs assessment designed to identify how many servicemembers and family members are in need of services, what their characteristics are, what types of assistance they need, and where they are located. A formal, comprehensive needs assessment conducted throughout DoD is a fundamental prerequisite for understanding what services are necessary for addressing psychological health and TBI. This needs assessment should establish the magnitude of demand for different types of services, the characteristics of individuals in need, and their geographic locations. This analysis should identify the full range of services needed, including need for clinical services, prevention and resilience training, and nonclinical support services, as well as the magnitude of the existing need. It should also describe the extent to which the routine care system—including clinical services and support services—currently meets those needs.

Recommendation 3.2: Conduct a formal gap analysis to identify how well programs are meeting the identified needs, opportunities that exist to improve current programs, and where need exists to develop new programs. A formal gap analysis would build on the information described in this report to provide an in-depth understanding of the extent to which existing programs meet the needs identified in the needs assessment and where gaps exist that warrant the development of new programs. When appropriate information is available and a gap analysis is feasible, it will be important to integrate the results of individual program evaluations to provide details on what types of programs and approaches work best and have the greatest likelihood of being expandable, replicable, or appropriately adapted for use in other settings.

Recommendation 3.3: Adopt a single, integrated conceptual framework for psychological health across DoD. Adoption of a single departmentwide conceptual framework would provide significant benefits, reducing the current confusion and ambiguity when attempting to examine psychological health services and programs across the branches of service and allowing programs to be categorized and evaluated consistently.

Reduce Barriers Faced by Programs

We found that programs encountered a number of barriers in the course of their efforts and focused our recommendations on some particularly notable barriers.

Recommendation 4.1: Continue widespread efforts to reduce stigma and institutional barriers associated with seeking treatment for mental health problems and traumatic brain injury. Efforts to reduce the stigma associated with receiving such care among servicemembers must continue. To effectively do so, it may be helpful for training messages within DoD to focus on mental health problems as part of a range of reactions to combat and operational stress, to emphasize help-seeking as an appropriate response, and to avoid setting unrealistically high expectations for resilience. To encourage servicemembers to seek care when needed, it must be evident to them that the career repercussions associated with seeking treatment are limited. There may also be opportunities to modify policy to reduce concerns in this area.

Recommendation 4.2: Improve continuity of services over the course of the deployment cycle and during transitions associated with permanent change of station. For servicemembers or family members participating in a program, continuity of care is important throughout the deployment cycle and across permanent change of station, and programs need a method to ensure such continuity. One model may be transitional coordination and coaching for servicemembers who are participating in programs or receiving clinical or supportive counseling services.

Recommendation 4.3: Improve the sharing of information across programs. One common issue that was raised by program representatives was the lack of information they had about other programs that were attempting to accomplish goals similar to theirs. Recommendations 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, and 5.5 include methods that may help to alleviate this concern.

Evaluate and Track New and Existing Programs, and Use Evidence-Based Interventions to Support Program Efforts

The lack of a process to systematically develop, track, and evaluate programs is likely to result in the proliferation of untested programs that are developed without an evidence base, an inefficient use of resources, and added cost and administrative inefficiencies. Further, it raises the potential that some programs—despite the best intentions of their originators—may cause harm or delay entry into the system of care, and that such harm would not be identified in a systematic or timely fashion.

Recommendation 5.1: The evidence base regarding program effectiveness needs to be developed. Existing programs and those under consideration for future development should be required to embed an ongoing evaluation in their efforts that addresses at least four key questions: (1) What works well? (2) What are the unanticipated consequences of the program? (3) What are the opportunities for improvement? (4) What lessons were learned during program implementation that can affect the successful transferability of the program to new organizations or locations? Where possible and appropriate, evaluations that contribute to this evidence base should draw from a common set of measures to allow for comparability across programs.

Recommendation 5.2: The evidence base regarding program effectiveness needs to be centralized and made accessible across DoD. New programs should be built on the existing evidence base wherever possible and should focus on one of three approaches: (1) replicating programs that have been evaluated and shown to be effective while employing available evidence regarding lessons learned and transferability; (2) utilizing evidence-based components of existing programs or other evidence-based approaches to care provision in order to develop new programs, with an evaluation designed as an inherent part of the program before it begins operation; or (3) using new treatments, techniques, or materials that are developed explicitly as pilot programs, incorporating a rigorous, detailed research study as an inherent part of the program before it begins operation, and not replicating or expanding the utilization of these new approaches until research and evaluation have shown them to be effective. The evidence base needs to be accessible across DoD to ensure that organizations that are considering the development of new programs or implementation of existing programs can utilize this information.

Recommendation 5.3: Programs that are shown to be ineffective should be discontinued and should not be replicated. If an evaluation is sufficiently rigorous and provides adequate evidence that a program is ineffective or is harmful, the program should be discontinued and should not be replicated elsewhere. Without such a policy and its uniform enforcement, DoD runs the continual risk of a poor investment of tax dollars in programs that have been demonstrated to be ineffective, are likely to have unintended consequences, and may harm servicemembers.

Recommendation 5.4: A central authority should set overall policies and establish guidelines regarding programs, including guidelines governing the proliferation of new programs. In order to avoid the proliferation of programs without adequate evidence and the duplication of effort across services to identify best practices, DoD should identify a central authority charged with the coordination of programs between branches of service and within OSD, centralization of the evidence base regarding program effectiveness (Recommendation 5.2), and ongoing tracking of programs (Recommendation 5.5).

Recommendation 5.5: Both new and existing programs should be tracked on an ongoing basis by a single entity, preferably the same organization that is charged with developing guidance regarding program proliferation. Over the long run, DoD needs to develop an infrastructure to build on this compendium and to ensure that its contents are kept current. One way to accomplish this is to require all ongoing and new programs to register with a centralized database and to provide key pieces of program information for inclusion in the database, such as program name, target population, point of contact, and key activities. In order to ensure that the compendium is complete, DoD should adopt a single definition of what constitutes a program.

Conclusions

A variety of factors—including increased news coverage regarding the psychological and cognitive consequences of deployment, the recommendations resulting from the work of highly visible advisory committees, the expanded numbers of mental health providers available in military clinical care settings, and the establishment of DCoE—have created significant motivation and momentum for developing programs to support servicemembers and their families.

While this attention is both necessary and laudable, the proliferation of programs creates a high risk of a poor investment of DoD resources. Our study suggests that there is significant duplication of effort, both within and across branches of service. Without a centralized evidence base, we remain uncertain as a nation about which approaches work, which are ineffective, and which are—despite the best intent of their originators—potentially harmful to servicemembers and their families. Given the financial investment that the nation is making in caring for servicemembers with mental health problems and TBI, servicemembers and their families deserve to know what these investments are buying. Strategic planning, centralized coordination, and the sharing of information across branches of service, combined with rigorous evaluation, are imperative for ensuring that these investments will result in better outcomes and will reduce the burden that servicemembers and their families face.

Notes

In some cases, it was difficult to identify whether an entity was best classified as a program or a resource.

Providing training, education, or support to servicemembers is not included here because it is the default activity for nearly all programs in this report, except those offering similar services to care providers.