Short abstract

This article describes a toolkit to help school-based mental health professionals, school personnel, and child welfare social workers adapt two school-based interventions for use with youth in foster care who have symptoms of distress following exposure to trauma.

Abstract

Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) was developed for use by school-based mental health professionals for any student with symptoms of distress following exposure to trauma. Supporting Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET) was adapted from CBITS for use by any school personnel with the time and interest to work with students affected by trauma. The purpose of this toolkit is to assist school-based mental health professionals, school personnel, and child welfare social workers in adapting these interventions for use with youth aged 10–15 who are in foster care. The authors note that delivering a school-based mental health program to youth in foster care has many challenges, including collaboration between the child welfare and education systems, confidentiality and information sharing policies regarding youth in foster care, and identification of these youth. The toolkit was designed to help understand these challenges and provide strategies for addressing them.

This article describes a toolkit to assist school-based mental health professionals and child welfare social workers in adapting Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) or Supporting Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET) for youth in foster care. CBITS is a manualized group program that was developed and initially evaluated in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). CBITS was developed for use by school-based mental health professionals for any student with symptoms of distress following exposure to trauma. SSET is adapted from CBITS for use by any school personnel with the time and interest to work with students affected by trauma. This toolkit was designed to help deliver CBITS or SSET to youth in foster care. To date, CBITS/SSET has been implemented only within schools, but it may also be possible to implement the programs in other settings, such as community-based mental health clinics, foster family agencies, child protective services (CPS) agencies, and other sites where youth in foster care are served. This resource does not replace the CBITS manual (available at: http://sopriswest.com/) or the SSET manual (available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR675/); instead it should be considered a supplement to be used in conjunction with either of the manuals when implementing the programs for youth in foster care.

As this brief review suggests, the research on the effects of child maltreatment on child and adolescent mental health provides key information that establishes that significant rates of single disorders and comorbid disorders that are present among these children. In spite of the need for mental health services for youth in foster care, numerous obstacles prevent adequate provision of these services to this population. This toolkit was developed in response to a clear need for accessible mental health treatment for youth in foster care to address their mental health needs.

This toolkit provides information and resources for implementing CBITS or SSET with youth in foster care. While CBITS/SSET has been implemented only within schools, it may also be possible to implement these programs in other settings, such as community-based mental health clinics, foster family agencies, CPS agencies, and other sites where youth in foster care are served. Depending on the setting, it is possible to form a group made up of only youth in foster care. The implementation steps recommended in this toolkit were based on the pilot project, which involved delivering CBITS to groups made up of only youth in foster care. However, the toolkit was also designed to help provide guidance for implementing and adapting CBITS or SSET in a mixed group with both youth in foster care and others.

In 2007, Casey Family Programs funded a pilot project to implement and evaluate an evidence- and school-based mental health intervention with early adolescents in foster care. The intervention, CBITS, is an evidence-based practice that had previously been implemented in the general education system in Los Angeles, primarily with school children of color. This toolkit was developed through our collaboration with a large urban school district, a county child welfare agency, and other community stakeholders on this project. The pilot project helped identify some of the challenges faced when implementing a mental health program for youth in foster care within the school system. Some of the implementation challenges included collaboration between the child welfare and education systems, confidentiality and information sharing policies regarding youth in foster care, and identification of youth in foster care. For more information about that pilot project, see Maher et al., 2009. We also conducted a focus group with foster care alumni, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) staff, and Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) staff for additional insights on adapting the program for youth in foster care.

While the toolkit has not yet been tested in multiple communities, the content of the toolkit was developed via a rigorous collaboration with foster care alumni and providers (educators, clinicians, social workers) who work with this population. The challenges faced during the pilot project effort helped shape the recommendations and strategies for implementing CBITS/SSET. This toolkit outlines the steps involved in preparing to implement CBITS/SSET with youth in foster care, including recommendations on how to form relationships to facilitate implementation; prepare to deliver services for youth in foster care; prepare participating youth for the program; adapt the program lessons, activities, and examples for youth in foster care; and follow up and track participants.

We hope that the toolkit provides concrete guidance on what to anticipate in planning, implementing, and evaluating the impact of CBITS or SSET for youth in foster care. This toolkit was designed to be used as a companion to the CBITS or SSET manual. Further, it should be used a starting point to increase dialogue among providers interested in improving how we address issues of trauma for this population.

CBITS Overview

What Is CBITS?

CBITS is an evidence-based, skills-based, cognitive and behavioral therapy intervention for reducing children's symptoms of PTSD, depression, and general anxiety caused by exposure to violence (Jaycox, 2004; Kataoka et al., 2003; Stein et al., 2003). The theoretical underpinnings are based on cognitive behavioral theory regarding anxiety and trauma. In short, this theory postulates that a traumatic event produces maladaptive assumptions and beliefs about the world (“It is extremely dangerous”), other people (“They cannot be trusted”), and the self (“I am not able to handle things”) that interfere with recovery. Moreover, extremely frightening events can create learned fear responses that may be quite disabling. In these situations, any trauma reminder can create a surge of anxiety. Over time, people who work to avoid such “triggers” in order to reduce the anxiety can have trouble recovering from the experience. Cognitive-behavioral therapies work to teach people skills to combat these underlying issues, including correction of maladaptive assumptions, processing the traumatic experience instead of avoiding it, learning new ways to reduce anxiety and solve problems, building peer and parent support, and building confidence to confront stress in the future.

CBITS was designed to overcome some of the barriers to youth receiving mental health services. The intervention is intended for children aged 10–15 (grades 5–9) who have had substantial exposure to violence and who have symptoms of PTSD in the clinical range. CBITS incorporates cognitive-behavioral therapy skills in a group format (6–8 students per group). CBITS is different from other types of therapy because it

provides structured sessions where skills are practiced

offers relatively simple tools that youth can use to reframe their stress and anxiety

combines group and individual sessions

includes sessions with parents and teachers

emphasizes collaboration between student and group facilitator.

What Skills Do Youth Learn?

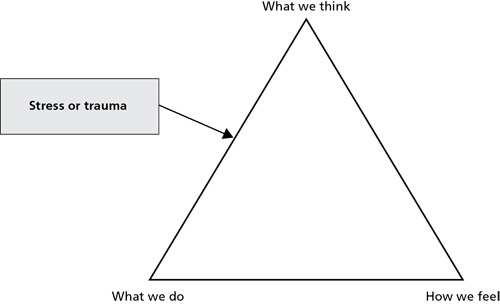

CBITS focuses on several types of skills that are useful for youth dealing with trauma. In short, CBITS focuses on helping students recognize the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and actions using the cognitive triangle (Jaycox, 2004), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Cognitive Triangle

The skills that youth learn to deal with their trauma include

relaxation

cognitive restructuring

addressing fears

social problem solving

reducing avoidant coping strategies.

What Are the Topics Covered in Each CBITS Session?

Each CBITS session usually begins with a debriefing from the last session and a review of homework, an overview of the new concept for the day's session, practice with that concept via a skills-based activity, and the assignment of homework related to that skill to be completed before the next session (Jaycox, 2004). The session topics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

CBITS Session Topics

| Session | Component |

|---|---|

| Child Sessions | |

| 1 | Introduction of group members, group procedures |

| 2 | Education about common reactions to stress or trauma |

| 3 | Thoughts and feelings: Introduction to cognitive therapy |

| 4 | Combating negative thoughts |

| 5 | Avoidance and coping |

| 6 | Exposure to stress or trauma memory through imagination, drawing, writing |

| 7 | Exposure to stress or trauma memory through imagination, drawing, writing |

| 8 | Introduction to social problem solving |

| 9 | Practice with social problem solving and combating negative thoughts |

| 10 | Relapse prevention and graduation ceremony |

| Parent Sessions | |

| 1 | Education about reactions to trauma, how we explain fear, relaxation |

| 2 | How we teach children to change their thoughts and actions |

| Teacher Session | |

| 1 | Education about reactions to trauma, elements of CBITS, tips for teaching youth who have been traumatized |

Who Should Conduct CBITS?

CBITS was developed for use by school-based mental health professionals. This toolkit does not replace the CBITS manual. Instead, it should be used in tandem with the CBITS manual. Mental health professionals who plan to implement the program with youth in foster care should use this resource to supplement the CBITS manual.

How Do We Know CBITS Works?

Two evaluations of the program have been published, both conducted under normal school conditions within LAUSD. In both studies, school-based clinicians were trained for two days on how to implement CBITS and were closely supervised throughout the implementation period to ensure quality and fidelity to the program.

The first study evaluated the program for recent immigrant Latino children in LAUSD schools in a quasi-experimental design, using social workers to implement the program (Kataoka et al., 2003). Students were randomly assigned to the treatment group or a wait list comparison group. At the three-month follow-up, depressive symptoms in the CBITS group significantly decreased (by 17 percent) but did not change in the wait-list group. PTSD symptoms in the CBITS group had significantly decreased at the three-month follow-up (by 29 percent) but did not decline significantly in the wait-list group. Of those students with clinical depressive symptoms at baseline, mean depression scores for the CBITS group dropped significantly at the three-month follow-up (by 22 percent), compared with a nonsignificant drop of 5 percent in the wait-list group. Of those students with clinically significant PTSD symptoms at baseline, follow-up scores declined significantly in the treatment group (by 35 percent), compared with a nonsignificant decline of 16 percent in the wait-list group.

The second evaluation was a randomized controlled study conducted during the 2001–02 academic year to assess the effectiveness of CBITS, using school mental health clinicians to implement the program (Stein et al., 2003). Students were randomly assigned to a ten-session standardized cognitive-behavioral therapy early intervention group or to a delayed intervention group conducted by trained school mental health clinicians. The sample consisted of sixth-grade students at two large middle schools in East Los Angeles. Data from students were collected at baseline, at three months, and at six months. At the three-month follow-up, students who received the CBITS intervention had significantly lower self-reported symptoms of PTSD and depression than students in the wait-list group. Parents of children in the CBITS intervention group reported significantly less psychosocial dysfunction for their children than parents of children in the wait-list group. Three months after completing the intervention, students who initially received the intervention maintained the level of improvement seen immediately after the program ended. At six months, improvement in children on the wait list (who had received CBITS prior to the six-month assessment) was comparable with that of those children who completed the program first.

In addition to these evaluations, CBITS has been implemented in other communities across the country, including ongoing work in the Los Angeles area. These communities include, among others, Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois, St. Louis, Missouri; Jersey City, New Jersey; Washington, D.C.; Denver, Colorado; Madison, Wisconsin; several Native American reservations in Montana and Minnesota; and the New Orleans, Louisiana, area. The implementation of CBITS in New Orleans followed closely after the hurricanes of 2005 and focused on post-disaster experiences as well as violence exposure.

SSET Overview

What Is SSET?

The SSET program was developed to train teachers and school counselors in the CBITS model. Since many schools face difficulties in terms of the availability of clinicians to work in schools, in 2009 researchers developed and pilot tested a modified version of the CBITS program that could be implemented by school staff who are not formally trained in mental health or clinical services.

As with CBITS, SSET is meant to be used with students who have experienced trauma and have symptoms of PTSD. SSET was developed for middle school students (ages 10–14) but it may also be useful for those in grades 4–9.

What Skills Do Youth Learn?

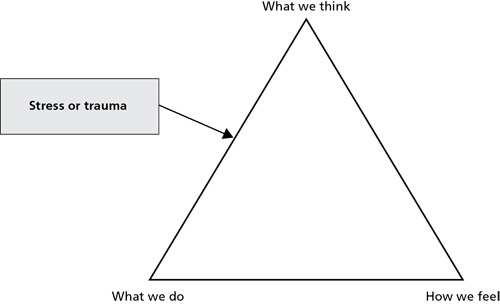

Like CBITS, SSET is a skills-based program designed to help youth deal with trauma. SSET also uses the cognitive triangle (Figure 2) to help students recognize how thoughts, feelings, and actions are related (Jaycox, Langley, and Dean, 2009). The skills taught are meant to help students change negative thoughts and to promote positive behavior.

Figure 2.

The Cognitive Triangle

What Are the Topics Covered in Each SSET Session?

The SSET sessions usually begin with a review of the agenda for the session and the homework from the previous session. The sessions then move to an introduction to the new concept and a skills-based activity to practice the concept. The sessions end with an explanation of the homework assignment and a review of how to use the skills introduced during the session to complete the homework (Jaycox, Langley, and Dean, 2009). The session topics are outlined in Table 2. The SSET manual describes the implementation process and provides lesson plans, materials, and activity sheets for each of the ten group sessions.

Table 2.

SSET Session Topics

| Session | Component |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Common reactions to trauma and strategies for relaxation |

| 3 | Thoughts and feelings |

| 4 | Helpful thinking |

| 5 | Facing your fears |

| 6 | Trauma narrative, part one |

| 7 | Trauma narrative, part two |

| 8 | Problem solving |

| 9 | Practice with social problems and helpful thinking |

| 10 | Planning for the future and graduation |

Who Should Conduct SSET?

SSET was adapted from CBITS for use by any school personnel, such as a teacher or counselor, with the time and interest to work with students affected by trauma. This toolkit does not replace the SSET manual.

How Do We Know SSET Works?

Results of a pilot test showed that this model was feasible for delivery by teachers and school counselors and acceptable to families and implementers. It showed promise in reducing depressive and PTSD symptoms, particularly among those who began the program with a higher level of distress (Jaycox et al., 2009).

Appropriateness of CBITS and SSET for Youth in Foster Care

As described earlier, youth in foster care often experience multiple and complex trauma and face challenges with the resulting emotional, behavioral, and social problems. Both CBITS and SSET are appropriate for youth in foster care because the programs focus on reducing trauma symptoms and providing skills to help students handle stress. In addition, both programs were developed with youth of color who closely match the racial/ethnic composition of youth in foster care.

Many youth in foster care do not obtain mental health services due to issues of access and service availability. CBITS or SSET overcomes these challenges by providing services in schools, where students spend much of their day. Given the transition and mobility issues for youth in foster care, schools can be a constant place for them where they can be easily reached.

More Information About CBITS or SSET

The CBITS manual is available at http://sopriswest.com/, and the SSET manual is available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR675/. In addition, more information about the CBITS and SSET programs can be found at http://www.rand.org/health/projects/cbits/.

Ongoing technical assistance and training in the CBITS model and other trauma-informed services for schools are offered through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Treatment Services Adaptation Center for Schools (www.tsaforschools.org). The center's Web site also contains information on various resources, including fact sheets, brochures, the Students and Trauma DVD, and the CBITS DVD.

Reference

- Jaycox, L. (2004). Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools. Longmont, CO: Sopris West Educational Services. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox, L. H., Langley, A. K., andDean, K. L. (2009). Support for Students Exposed to Trauma: The SSET Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox, L. H., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., Wong, M., Sharma, P., Scott, M., andSchonlau, M. (2009). Support for Students Exposed to Trauma: A pilot study. School Mental Health 1 (2), 49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka, S. H., Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Wong, M., Escudero, P., Tu, W., Zaragoza, C., andFink, A. (2003). A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42 (3), 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher, E., Jackson, L., Pecora, P. J., Schultz, D. J., Chandra, A., andBarnes-Proby, D. S. (2009). Overcoming challenges to implementing and evaluating evidence-based interventions in child welfare: A matter of necessity. Children and Youth Services Review, 31 (5), 555–562. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Wong, M., Tu, W., Elliot, M. N., andFink, A. (2003). A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290 (5), 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]