Abstract

Study Objectives:

Limited data exist on the association between trauma and sleep across developmental stages, particularly trauma experienced in childhood and sleep in adulthood. We assessed sleep quality across the developmental spectrum among avalanche survivors 16 years after exposure as compared to a matched comparison cohort.

Methods:

Participants were survivors of two avalanche-affected towns (n = 286) and inhabitants of non-exposed towns (n = 357). Symptoms were assessed with respect to the survivors' developmental stage at the time of the disaster: childhood (2–12), adolescence (13–19), young adult (20–39), and adult (≥ 40). The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PTSD Addendum were used.

Results:

Overall PTSD symptoms were not associated with avalanche exposure in any age groups under study. However, survivors who were children at the time of the disaster were 2.58 times (95% CI 1.33–5.01) more likely to have PTSD-related sleep disturbances (PSQI-A score ≥ 4) in adulthood than their non-exposed peers, especially symptoms of acting out dreams (aRR = 3.54; 95% CI 1.15–10.87). Those who were adults at time of the exposure had increased risk of trauma-related nightmares (aRR = 2.69; 95% CI 1.07–6.79 for young adults aRR = 3.07; 95% CI 1.51–6.24 for adults) compared to their non-exposed peers.

Conclusions:

Our data indicate a chronicity of PTSD-related sleep disturbances, particularly among childhood trauma survivors. REM sleep disturbances may have different manifestations depending on the developmental stage at the time of trauma exposure.

Citation:

Thordardottir EB, Hansdottir I, Valdimarsdottir UA, Shipherd JC, Resnick H, Gudmundsdottir B. The manifestations of sleep disturbances 16 years post-trauma. SLEEP 2016;39(8):1551–1554.

Keywords: trauma, sleep, posttraumatic stress, development, children

Significance.

This study advances previous knowledge about sleep disturbances post-trauma, indicating potentially different manifestation of REM sleep disturbances in childhood versus adult survivors. Specifically, adults are possibly at increased risk for persistent nightmares post-trauma, while children are at greater risk of acting out dreams. Taking into account the developmental stage at the time of trauma may be important when assessing and treating sleep disturbances in trauma-exposed populations.

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic events have been found to be associated with sleep problems such as nightmares and insomnia in both children and adults.1,2 Sleep disturbances are a core feature of PTSD and have been documented during both REM and NREM sleep stages.3,4 Nightmares, predominantly occurring in REM sleep and acting out dreams, symptoms caused by loss of REM atonia, have been reported in adult trauma survivors.5 Sleep terrors, anxiety, and panic attacks, which occur predominantly out of NREM sleep, have also been associated with trauma exposure. Furthermore, disruptive nocturnal behaviors (DNB) such as excessive movements and vocalizations have been found to be characteristic of survivors of trauma in adulthood.6

Despite each developmental period during the life span being characterized by different sleep behaviors,7 the association between sleep problems and trauma recovery is poorly understood across the developmental stages. Scientific knowledge about the relationship between sleep and trauma is mainly based on trauma occurring in adulthood,2 and to date, the adult and child literature on trauma and sleep have remained separate.

The current study assessed the sleep quality of disaster survivors 16 years post-trauma. In 1995, two avalanches fell on isolated towns in Iceland, taking the lives of 34 inhabitants. Based on the same cohort utilized in the current study, we previously reported that survivors were significantly more likely to experience general sleep impairment, PTSD-related sleep disturbances, and symptoms of PTSD hyperarousal than a comparison group 16 years post-disaster.8 In the current study, we further explored the potential modifying effects of developmental stage at the time of the trauma on subsequent sleep-related symptomology.

METHODS

Participants

Through residential records from 1995 we attempted to contact all living residents of the avalanche-affected towns (exposed group) and two towns not geographically threatened by avalanches (comparison group), who were 18 years or older in 2011. Response rate for the avalanche survivors was 72% (286/399; 50% men, 50% women) and 66% (357/541; 46% men, 54% women) in the comparison group. More information about the data collection process is available in our previous report.8

Young adults in the exposed group were more likely to have poor or very poor financial status than young adults in the comparison group (χ2 = 10.77, P < 0.01). In addition, adults in the exposed group were more likely to have children than adults in the comparison group (χ2 = 7.08, P < 0.01). No signifi-cant differences were found between the avalanche-exposed and comparison groups with regard to other demographic variables (see Table S1 in supplemental material).

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information was gathered for gender, age, education, finances, number of children, current living situation, and employment status. Developmental stages were divided into the following phases, built on Erik Erikson's psychosocial phases of human development: childhood (ages 2–12), adolescence (ages 13–19), young adult (ages 20–39), and adult (age ≥ 40).9,10 Education was classified according to the Icelandic school system, where grade school is compulsory for children 6 to 16 years old, followed by a 4-year elective high school education (for most completed at 19).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI11 was used to assess general sleep problems in the past month. A PSQI global score > 5 was used to indicate clinically significant sleep problems.11 The coefficient α in the total sample was 0.82.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Addendum for PTSD (PSQI-A)

The PSQI-A6 was used to assess the frequency of disruptive nocturnal behaviors common in PTSD. A clinical score ≥ 4 was used, which discriminates between participants with and without PTSD.6 When results for each item on the questionnaire were analyzed independently, a score > 1 was used to indicate symptomology. The coefficient α in the total sample was 0.74.

The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS)

The 17 questions on the PDS12 corresponding to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD were used. The comparison group answered the standard questionnaire. For the exposed group, the PDS was modified, with questions being avalanche-specific. A standard cutoff > 14 was used, which is indicative of clinically significant PTSD symptoms.13 The coefficient α in the total sample was 0.92.

Statistical Analysis

We used poisson log-linear models with robust error variance to obtain relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of morbidity in the avalanche group. The RRs represent a ratio of the proportion of exposed subjects versus subjects in the comparison group, with index outcome or characteristic in each line. Adjustments were made for gender. The statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 was used to conduct analysis.

RESULTS

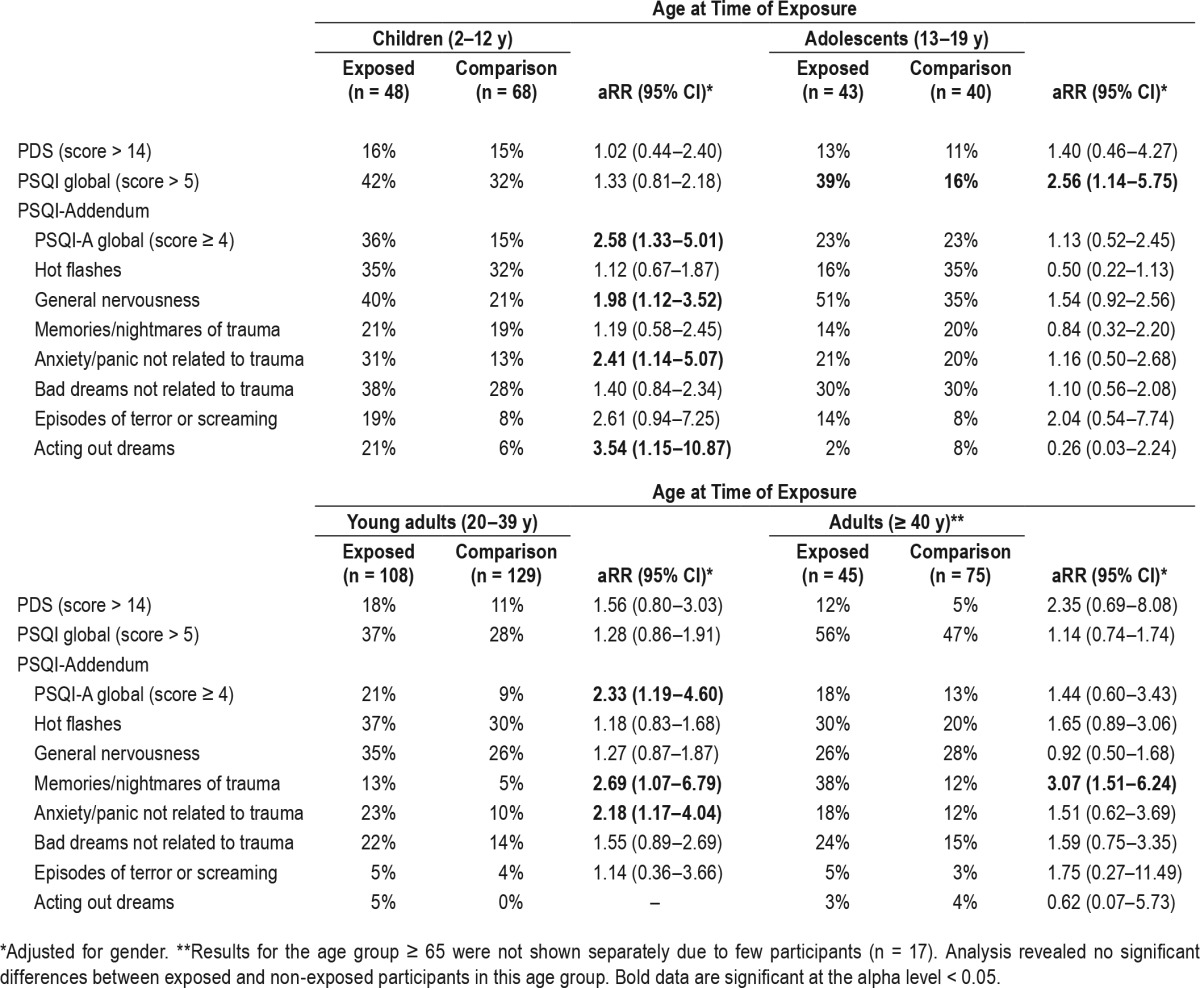

At the time of exposure survivors who were children were 2.58 times more likely to have PTSD-related sleep disturbances than their non-exposed peers 16 years post-trauma. Specifically, childhood survivors were more likely to experience symptoms of general nervousness (aRR = 1.98), anxiety or panic not related to trauma (aRR = 2.41), and acting out dreams (aRR = 3.54) than their non-exposed peers. No significant associations were found with regard to general sleep problems or PTSD symptoms between survivors who were children at the time of exposure and their non-exposed peers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

PTSD symptoms and sleep disturbances in avalanche survivors and the comparison group with regard to age at the time of the disaster.

Avalanche survivors who were adolescents at the time of exposure were more likely to experience general sleep problems (aRR = 2.56) than their non-exposed peers 16 years after trauma. No statistical difference was found with regard to PTSD symptoms and PTSD-related sleeping problems between survivors who were adolescents at the time of exposure and their non-exposed peers (Table 1).

Survivors who were young adults at the time of the trauma were more likely to experience PTSD-related sleep disturbances (aRR = 2.33), particularly memories or nightmares of trauma (aRR = 2.69) and anxiety or panic not related to trauma (aRR = 2.18) than their non-exposed peers. No statistical difference was found with regard to general sleeping problems and PTSD symptoms between survivors who were young adults at the time of exposure and their non-exposed peers (Table 1).

No statistical difference was found with regard to general sleeping problems and PTSD symptoms between survivors who were adults at the time of exposure and their non-exposed peers 16 years after trauma. Furthermore, we found no statistical difference between the groups on the global score on the PSQI Addendum for PTSD. However, exposed survivors who were adults at the time of the trauma were more likely to experience memories or nightmares of trauma (aRR = 3.07) 16 years later than their non-exposed peers (see Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In our 16-year follow-up of two avalanche-stricken communities, we found that the manifestations of sleep disturbances varied depending on survivor's developmental stage at the time of the trauma. Survivors who were children at the time of exposure were, 16 years later, more than twice as likely to have PTSD-related sleep disturbances, particularly symptoms of acting out dreams (e.g., kicking, punching, running, or screaming while asleep) than their non-exposed peers. Contrary to the manifestation of sleep disturbances in childhood survivors, we found that trauma-related nightmares were more prevalent among those who were adults at the time of the trauma than their non-exposed peers at follow-up.

The most notable finding in our study is the high prevalence of acting out dreams among childhood survivors, suggesting that the preteen years may be a sensitive period to the development of trauma-related motor pathologies during sleep. Motor activity characteristic of REM behavior disorder has previously been reported among individuals with PTSD after trauma occurring in adulthood.14,15 With regard to survivors of trauma in childhood, a recent sleep physiology study16 found that early lifetime traumatic event exposure was associated with REM sleep fragmentation in adulthood. Interestingly, REM sleep fragmentation was also associated with later life disruptive nocturnal behavior in the study. It is possible that childhood trauma affects the development of REM sleep physiology, causing lasting disruptions in the REM sleep phase. However, further studies are needed to assess the possible connection between childhood trauma and REM sleep disturbances in adulthood.

Consistent with previous literature, we found that trauma-related nightmares were more prevalent among those who were adults at the time of the trauma than their non-exposed peers.17 Traumatic nightmares are primarily a phenomenon of REM sleep, as is acting out dreams.18 Our findings therefore indicate potentially different manifestation of REM sleep disturbances in childhood versus adult survivors. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has speculated that there is a common underlying pathophysiologic mechanism in REM sleep disturbances.18 It is possible that the effect of trauma on REM sleep manifests differently depending on the developmental stage at the time of the trauma. Perhaps adults are rather at relatively increased risk for persistent nightmares post-trauma, while children are at greater risk of acting out dreams.

This study advances previous research that associates trauma and PTSD related sleep disturbances in children and adults by looking at developmental stages at the time of trauma. Through nationwide registers providing information about the total avalanche-stricken population and with a response rate of 72%, our study is highly representative of the pre-disaster population. However, our study is limited by self-report measurements of sleeping disturbances. It is noteworthy that the exposed and comparison group were distinguished by sleep disturbances, not PTSD symptoms. However, the PTSD symptom attribution in the exposed group was restricted to the avalanche exposure, and the comparison of symptoms between groups is therefore conservative.

To date, the long-term trajectories of sleep pathology in traumatized children have not been fully documented. Future prospective longitudinal research is needed to assess whether trauma-related sleep disturbances manifest differently in childhood as opposed to adulthood.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study was funded by the University of Iceland Research Fund, the Icelandic Research Fund for Graduate Students (Rannis), the Landspitali University Hospital Research Fund, and the Nordic Centre of Excellence for Resilience and Societal Security (NORDRESS), which is funded by the Nordic Societal Security Programme. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Harpa Jonsdottir for her help in collecting data and the late Jakob Smari for his invaluable support in initiating and designing this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Safe enough to sleep: sleep disruptions associated with trauma, posttraumatic stress, and anxiety in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;18:877–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babson KA, Feldner MT. Temporal relations between sleep problems and both traumatic event exposure and PTSD: a critical review of the empirical literature. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spoormaker VI, Montgomery P. Disturbed sleep in post-traumatic stress disorder: secondary symptom or core feature? Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:169–84. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi I, Boarts JM, Delahanty DL. Polysomnographically measured sleep abnormalities in PTSD: a meta-analytic review. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:660–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mysliwiec V, O'Reilly B, Polchinski J, Kwon HP, Germain A, Roth BJ. Trauma associated sleep disorder: a proposed parasomnia encompassing disruptive nocturnal behaviors, nightmares, and REM without atonia in trauma survivors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:1143–8. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germain A, Hall M, Krakow B, Katherine Shear M, Buysse DJ. A brief sleep scale for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Addendum for PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Ambrosio C, Redline S. Sleep across the lifespan. In: Redline S, Berger NA, editors. Impact of sleep and sleep disturbances on obesity and cancer. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thordardottir EB, Valdimarsdottir UV, Hansdottir I, Resnick H, Shipherd J, Gudmundsdottir B. Posttraumatic stress and other health consequences of catastrophic avalanches: a 16-year follow-up of survivors. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;32:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erikson EH. Life cycle. In: Sills DE, editor. International encyclopedia of the social sciences. New York, NY: Crowell, Collier; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erikson EH. Childhood and society. 2nd ed. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatr Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:445. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey SF, Gudmundsdottir B, Beck JG, Palyo SA, Miller L. Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors using the PSS-SR and IES. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:119–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. REM sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:148–57. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross RJ, Ball WA, Dinges DF, et al. Motor dysfunction during sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep. 1994;17:723–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Insana SP, Kolko DJ, Germain A. Early-life trauma is associated with rapid eye movement sleep fragmentation among military veterans. Biol Psychol. 2012;89:570–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreuder BJ, Kleijn WC, Rooijmans HG. Nocturnal re-experiencing more than forty years after war trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:453–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1007733324351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed. Diagnostic and coding manual. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.