Abstract

Study Objectives:

This study aimed to explore the moderation of pubertal status on the onset of sex differences in the prevalence of insomnia symptoms and their health correlates.

Methods:

A total of 7,507 children and adolescents (weighted percentage of female: 48.5%) aged between 6–17 y were recruited from thirty-one primary and secondary schools. Participants with difficulty initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS), and/or early morning awakening (EMA) ≥ 3 times/week in the past month were considered as having insomnia symptoms. The severity of insomnia was measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

Results:

The prevalence of insomnia symptoms increased from 3.4% to 12.2% in girls (3.6-fold) and from 4.3% to 9.1% in boys (2.1-fold) from Tanner stage 1 to 5. There was a significant interaction between sex and Tanner stage in the prevalence of insomnia (P < 0.001) with an emergence of female preponderance at Tanner stage 4 even after controlling for age, family income, and school start time. Similar sex-Tanner stage interactions were found in DIS, DMS, and ISI total score but not EMA. Insomnia symptoms were strongly associated with behavioral problems, poor mental health, and poor general health in both sexes. Boys with insomnia would report more maladaptive lifestyles (smoking, alcohol, and energy drinks) whereas girls with insomnia were more susceptible to emotional and relationship difficulties.

Conclusions:

Pubertal maturation was associated with a progressive increase in the prevalence of insomnia symptoms with the emergence of female preponderance in both the prevalence and severity of insomnia symptoms at late puberty.

Clinical Trials Registration:

Chinese Clinical Trial Register, http://www.chictr.org.cn, ID: ChiCTR-TRC-12002798

Citation:

Zhang J, Chan NY, Lam SP, Li SX, Liu Y, Chan JW, Kong AP, Ma RC, Chan KC, Li AM, Wing YK. Emergence of sex differences in insomnia symptoms in adolescents: a large-scale school-based study. SLEEP 2016;39(8):1563–1570.

Keywords: adolescents, insomnia symptoms, pubertal status, sex differences

Significance.

Adolescence is a critical phase for an approximate threefold increase of the prevalence of insomnia symptoms, especially for girls. The female predisposition in insomnia, except for early morning awakening, starts to emerge at late and post puberty. Insomnia in children and adolescents was associated with behavioral problems, poor mental and general health in both sexes but boys with insomnia would report more maladaptive lifestyle habits whereas girls were more susceptible to emotional and relationship difficulties. Further study is needed to investigate the mechanisms underlying the role of puberty in leading to sex differences in insomnia. Our findings also suggested that late childhood and adolescence represent a critical period for early intervention and prevention of insomnia.

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia symptoms are prevalent in the general population.1–4 Female sex,3 low socioeconomic status,1 stressful life events1, and poor general and mental health3 are commonly identified as the risk factors for insomnia. In particular, female sex is a consistent risk factor for insomnia in adult and elderly populations in terms of the higher prevalence, more persistent natural course, and more serious health-related repercussions.5,6 Stronger effects of insomnia symptoms on pain perception,7 increased cortisol awakening response,8 and resistant hyper-tension9 were found in adult females when compared with adult males.

Interestingly, most studies did not find any sex differences in insomnia in children.1,10,11 Thus, puberty has been postulated as a critical stage for the development of insomnia and the emergence of the sex differences in insomnia.12–15 Indeed, puberty is accompanied by a series of changes that may seemingly contribute to the development of insomnia, such as a decreased homeostatic sleep drive and an intrinsic delayed circadian phase leading to a mismatch between the teen's circadian pattern and social activities.16 Several studies have explored the timing of sex differences in insomnia.13–15 Johnson et al.14 found that onset of menses was a critical phase of increased risk of developing insomnia in adolescent girls but pubertal maturation was not associated with increased prevalence of insomnia in adolescent boys. However, none of these studies included a wide range of samples covering both children and adolescents, which might have limited their ability to determine the sex differences in insomnia from pre-puberty/early puberty to late puberty/post-puberty. As pubertal development is a continuous process across late childhood to adolescence, the inclusion of both children and adolescents would allow for the exploration of the development of insomnia symptoms across different stages of puberty in both boys and girls.

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that insomnia symptoms are associated with widespread mental and physical health problems in children and adolescents.3,4,17–20 Puberty is also a critical period for the onset of many mental and physical disorders that are closely associated with insomnia symptoms. In this regard, it is necessary to investigate the potential moderating effects of puberty on the association between insomnia symptoms and various health outcomes. Hence, we hypothesized that puberty plays a critical role in the development and emergence of female preponderance of insomnia symptoms. We aimed to determine the onset of sex differences in insomnia symptoms and their subtypes across different stages of puberty. We also aimed to explore whether the associations of insomnia symptoms with mental and general health problems are moderated by sex and pubertal status.

METHODS

Sample Recruitment

This study was part of a large-scale sleep education program that recruited students from both primary and secondary schools (ChiCTR-TRC-12002798). The original study aimed to examine the effectiveness of a multilevel and multimodal school-based education program to improve sleep knowledge, sleep pattern, and lifestyle practice.21 The current study was based on the baseline data of this interventional study. In brief, 16 primary schools and 15 secondary schools in Hong Kong agreed to take part in the sleep education program between December 2011 and March 2012. The school start time was reported by individual schools (range: 07:50–08:45). The school start time was slightly earlier in secondary schools than primary schools (08:06 ± 0:11 versus 08:18 ± 0:13, P < 0.001). After obtaining the consent form at the schools, an envelope containing sleep questionnaires, parental consents, and individual assents was distributed to each student with the help of the teachers. The students were instructed to bring the questionnaires back home for completion by themselves (for secondary school students) or their parents/caretakers (for primary school students). We advised the person who filled in the questionnaires to consult or discuss with the relevant family members in order to minimize reporting bias. Both parent(s)/ caregiver(s) and the students gave written consents and assents to the study, respectively. Ethical approval was obtained from the Joint CUHK-NTEC clinical research ethics committee (reference no: CRE-2011.249-T).

Insomnia Symptoms Assessment

The questions on insomnia symptoms were derived according to International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition (ICSD-2).22 Three subtypes of insomnia were measured by the following questions: “In the past month, how often has your child (you) had (1) difficulty in falling asleep? (2) Sudden awakening during sleep and difficulty in returning to sleep? (3) Early morning awakening and difficulty in returning to sleep?”. All the questions about insomnia were rated in a five-point Likert scale (“1” = never, “2” = less than once per month, “3” = one to three times per month, “4” = once or twice per week, “5” = at least three times per week). Those children and adolescents with a response of “at least three times/week” on any insomnia item were considered as having insomnia symptoms.

Insomnia Symptoms Severity

The severity of insomnia symptoms was measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).23The ISI has been validated in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents and has been shown to have good psychometric properties.24 The score of the ISI ranges from 0 to 28. A score of ≥ 9 on ISI was the optimal cut-off (sensitivity/specificity: 0.87/0.75) to determine insomnia problem in Chinese adolescents.24

Pubertal Status

Pubertal status was categorized by Tanner staging using a self-assessment questionnaire, which is an adaptation of an interview-based puberty rating scale. The Tanner scale is a tool to measure pubertal development as based on the external primary and secondary sex characteristics, such as the size of the breasts (for females) and genitals (for males), and the development of pubic hair.25 The Tanner stage scale has been validated in both Chinese boys and girls.26,27 In addition, the validated self-reported scale has excellent agreement with the rater-rated assessment in Chinese adolescents.28 When determining the pubertal status, both breast/genital development and pubic hair development were considered. The higher stage of breast/ genital or pubic hair development defined the corresponding Tanner stage. For example, a boy with genital stage of 3 and pubic hair stage of 2 would be coded as Tanner stage 3.

Outcome Measures

A series of lifestyle, behavioral difficulties, and mental and general health problems were measured. The following question was asked: “How is your child's (your) general health condition in the recent 1 mo?” Those with a response of “poor” or “very poor” were considered as having poor perceived health. Lifestyle habits, including regular consumption of tea, coffee, energy drinks and alcohol, and smoking, were measured. Those participants with a frequency of “sometimes” or “often” were considered regular users. Questions on smoking and consumption of alcohol were only asked in the questionnaire for secondary school students (by self-report).

The Chinese version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was employed to evaluate the mental health status of the adolescents.29 It has been shown that the Chinese version of GHQ-12 has satisfactory psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and good factorial structure.30 As the GHQ-12 was only validated in adolescents but not in children, it was only included in the questionnaires for secondary school students (by self-report). The GHQ scoring method (0-0-1-1) was chosen over the simple Likert scale of “0”, “1”, “2”, and “3”. The total score of the GHQ-12 ranges from 0–12 and a total score of ≥ 4 on the GHQ-12 suggests poor mental health.31

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a 25-item brief screening questionnaire on emotional and behavioral well-being, focusing on the following five aspects: peer relationships, hyperactivity/inattention, prosocial behaviors, emotional problems, and conduct problems. A total score of “total difficulties” of SDQ was calculated as the sum of the scores of all subscales, except for the prosocial aspect. The SDQ was completed by the students themselves for those in secondary schools and was completed by the students' parent/ caregiver for those in primary schools. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Chinese version of SDQ has high levels of reliability and validity in measuring psychopathology in both Chinese children and adolescents.32,33 The cut-offs for identifying abnormal cases were based on the following web-site: http://www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/c0.py.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as percentages for discrete variables and as means (standard deviations) for continuous variables. In view of potential reporting bias, all analyses were weighted for age and sex according to the school data in Hong Kong (http://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/about-edb/publications-stat/figures/Enrol_2011.pdf). The differences in the sample characteristics among participants across different Tanner stages were tested by independent chi-square test or analysis of variance where appropriate. Interaction term was used to determine the sex*Tanner stage interaction on insomnia symptoms and its subtypes after controlling for age, sex, and family income (Figure 1). Logistic regression models were also used to explore the associations of insomnia symptoms with mental and general health as well as behavioral problems after controlling for age, family income, school start time, and Tanner stage in boys and girls, respectively. The interaction of “insomnia*sex” was additionally included into the models. Covariate analysis was employed to compare the mean differences in the ISI total scores between boys and girls across different Tanner stages after controlling for age, sex, and family income. Interaction between sex and Tanner stage was also tested in covariance analysis (Figure 2A). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

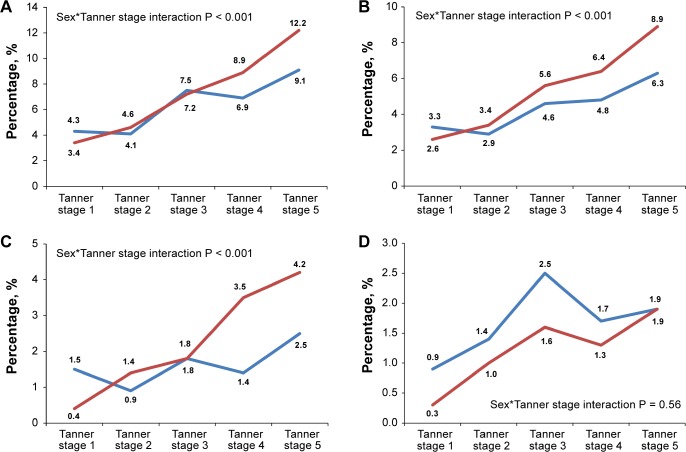

Figure 1.

Sex-specific weighted prevalence of insomnia symptoms and subtypes across different Tanner stages. (A) Overall insomnia symptoms. (B) DIS. (C) DMS. (D) EMA. Weighted for age. DIS, difficulty initiating sleep; DMS, difficulty maintaining sleep; EMA, early morning awakening.

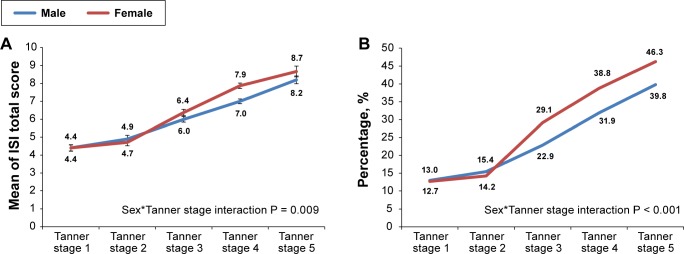

Figure 2.

Sex and Tanner stage interaction in the severity of insomnia symptoms. (A) ISI total score. (B) ISI ≥ 9. Weighted for age and sex. Bars represent standard errors of the mean. ISI, Insomnia Severity Index.

RESULTS

A total of 19,341 students were eligible to participate in this study, and 55.2% of them (n = 10,671) returned the questionnaires. All students were recruited during the school terms and the majority of them (93.8%) returned the questionnaires between January and February 2012. Among the respondents, 7,507 (70.3%) had valid data on both insomnia symptoms and Tanner stage. Those respondents with valid data were more likely to be girls (75.5% versus 67.4%, P < 0.01) and slightly older (12.4 ± 3.5 y versus 11.9 ± 3.6 y, P < 0.01) than those without valid data. The questionnaires for primary school students (n = 3,083) and secondary school students (n = 4,424) were completed by parents/guardian and students themselves, respectively. The age range was from 6 y to 14 y (99.3% aged 12 y or younger) for primary school students and 11–17 y (84.7% aged 13 y or older) for secondary school students. Among those questionnaires returned by the primary school students, 2,220 (72.4%) were completed by mothers, 585 (19.0%) were completed by fathers, and the remaining questionnaires (n = 278, 9.6%) were completed by other caregivers, such as the child's grandparent or aunt.

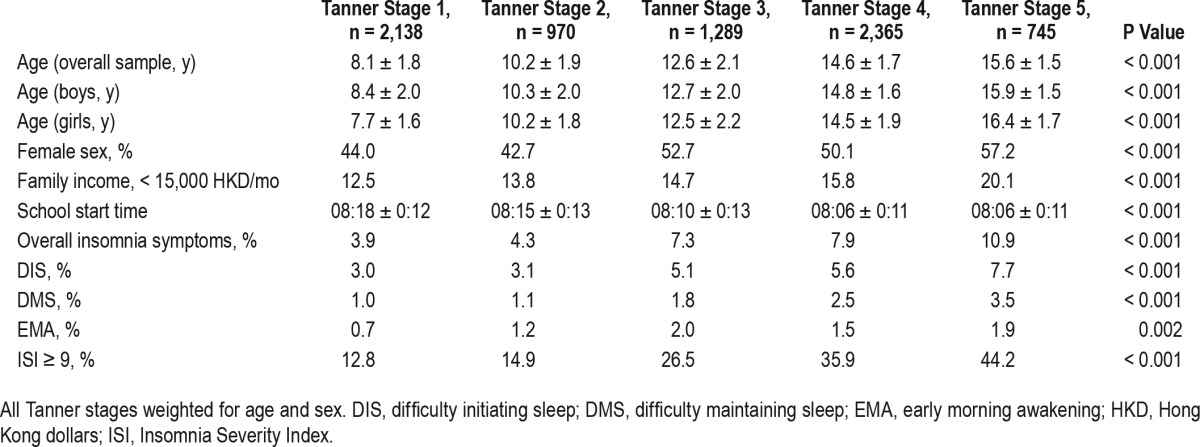

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants across different stages of puberty. A total of 7,507 participants (weighted percentage of girls: 48.5%) aged from 6 to 17 y were recruited. The overall prevalence of insomnia symptoms in the past month was 6.5%. Table 1 shows the prevalence of overall insomnia symptoms and their subtypes across different pubertal stages. The prevalence of overall insomnia symptoms increased significantly from 3.9% to 10.9% across Tanner stages 1 to 5. The prevalence of insomnia was rather similar between participants at Tanner stage 1 and 2 (3.9% versus 4.3%), but dramatically increased at Tanner stage 3 (7.3%). Similar associations with Tanner stages were also found for difficulty initiating sleep (DIS, from 3.0% at Tanner stage 1 to 7.7% at Tanner stage 5), difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS, from 1.0% at Tanner stage 1 to 3.5% at Tanner stage 5), and “insomnia symptoms” as defined as “ISI ≥ 9” (from 12.7% at Tanner stage 1 to 44.2% at Tanner stage 5). The associations of Tanner stage with various insomnia subtypes, except for early morning awakening (EMA), persisted after controlling for age and sex (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of subjects across different pubertal status (n = 7,507).

Figure 1 delineates the sex and pubertal interactions on the prevalence of overall insomnia symptoms and its subtypes. There was a significant interaction between sex and pubertal maturation in the prevalence of insomnia symptoms (P < 0.001). The prevalence of insomnia symptoms progressively increased across pubertal maturation (Tanner stage 1 to 5), from 3.4% to 12.2% for girls (3.6-fold) and 4.3% to 9.1% for boys (2.1-fold). For the participants at Tanner stages 1–3, the prevalence of overall insomnia symptoms was very similar between boys and girls (Figure 1A). However, there was a higher prevalence of overall insomnia symptoms in girls than boys when they reached Tanner stages 4 and 5 (Interaction P < 0.001). Significant interactions between sex and pubertal stages were also found for DIS and DMS but not EMA (Figure 1B–1D). Female preponderance seemed to occur slightly earlier for DIS, starting at Tanner stage 3 (Figure 1B), than DMS (started at Tanner stage 4, Figure 1C). The sex*Tanner stage interactions on DIS, DMS, and overall insomnia symptoms remained statistically significant after adjustment for age, family income, and school start time (P < 0.01).

Figure 2 shows the results as measured by the ISI total score. In terms of insomnia severity, the mean ISI total score increased from 4.4 to 8.7 for girls and from 4.4 to 8.2 for boys across Tanner stages 1 to 5. The mean ISI total score was comparable between boys and girls at prepubertal and early pubertal status (Tanner stages 1–2) but was consistently higher in girls than boys across Tanner stages 3 to 5 (interaction P < 0.001). Girls started to have a higher rate of insomnia symptoms, defined as ISI ≥ 9, than boys when they reached Tanner stage 3 or above. Additional adjustment for age, family income, and school start time did not change the sex*Tanner stage interaction effects on ISI total score and insomnia symptoms (P < 0.001).

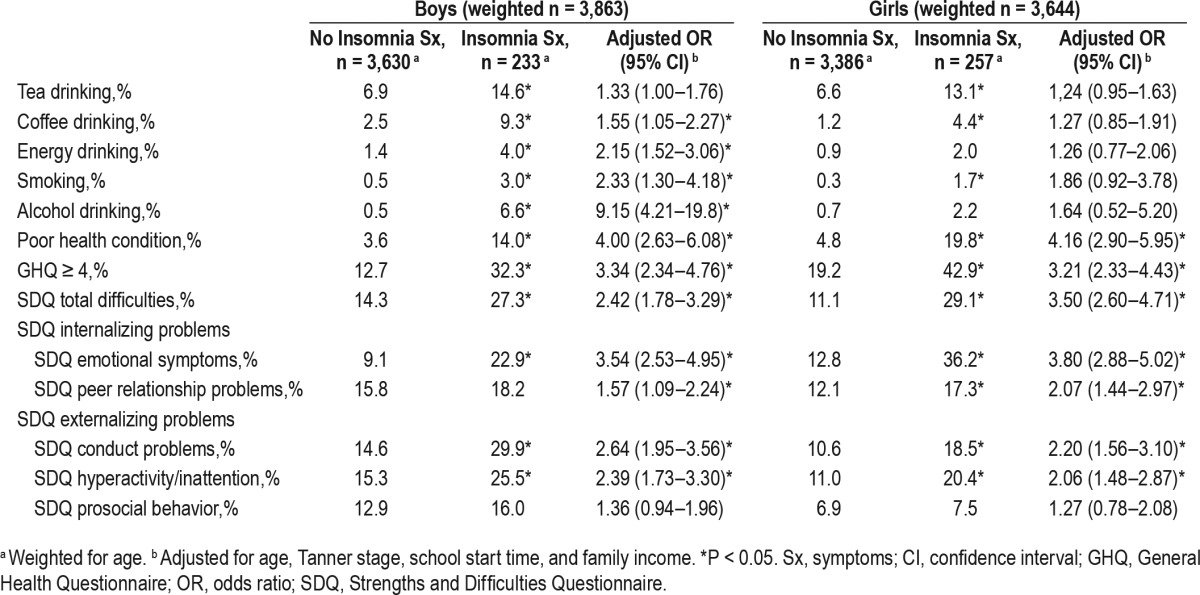

Table 2 shows the associations of insomnia symptoms with lifestyle practices, emotional and behavioral problems, and perceived general health in boys and girls, respectively. After controlling for age, Tanner stage, family income, and school start time, insomnia symptoms were significantly associated with various health measures, including poor health condition, higher GHQ score, SDQ total difficulties, SDQ emotional symptoms, SDQ peer relationship problems, SDQ conduct problems, and SDQ hyperactivity/inattention in both boys and girls. Further interaction analyses found that insomnia symptoms were associated with more maladaptive lifestyle practices, especially the consumption of energy drinks (interaction P = 0.040) and alcohol (interaction P = 0.013) in boys, whereas girls with insomnia symptoms were much more susceptible to present with overall difficulties in the Strengths and Difficul-ties Questionnaire (interaction P = 0.020).

Table 2.

Associations of insomnia symptoms with medical and behavior problems in boys and girls, respectively.

Additional Sensitivity Analyses

For primary school students, the majority of the questionnaires were completed by their mothers (72.4%) and approximately one-fifth of the questionnaires (19.0%) were completed by their fathers. We compared the major outcomes of insomnia phenotypes between children whose information was reported by mothers and fathers respectively. There were no differences in the prevalence of insomnia variables (including overall insomnia symptoms, DIS, DMS, EMA, ISI ≥ 9) when the questionnaires were completed by mothers compared to fathers. However, ISI total score was slightly higher when rated by mothers compared to fathers (mean ± standard deviation = 4.44 ± 3.72 versus 4.01 ± 3.47, P = 0.015). Nonetheless, the major findings of sex*Tanner stage interactions on the prevalence of DIS, DMS, overall insomnia symptoms, ISI ≥ 9, and the ISI total score remained unchanged even after taking into account the difference of the informants (e.g. mothers versus fathers) in the analyses.

DISCUSSION

Several interesting findings are worth noting in the current study. First, adolescence appears to be a critical phase for the increased prevalence of insomnia symptoms in both boys and girls. Second, this study delivered a clear message that puberty plays a critical role in the emergence of sex differences in insomnia symptoms with regard to its prevalence, subtypes, and severity. In particular, female predisposition was found to start to emerge at late puberty/post-puberty. Finally, insomnia symptoms were significantly associated with various mal-adaptive lifestyles, emotional and behavioral problems, and poor general health in both boys and girls, albeit with some sexual dimorphisms, even when the pubertal status is taken into account.

Although two previous studies reported that pubertal status is not associated with increased prevalence of insomnia in adolescent boys,14,15 we found that there were threefold increases in the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in the overall sample across pubertal maturation. In particular, there was a twofold and nearly fourfold increase in the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in boys and girls, respectively. These two previous studies only included either children14 or adolescents,13 whereas our study included participants with a wider range of age (6 to 17 y, including both children and adolescents). Another possible explanation for the discrepancy of the findings between studies is that, cultural differences, such as increased academic stress in local Chinese adolescents, may interact with the pubertal status to increase the risk of developing insomnia symptoms in Chinese adolescent boys and girls. In this regard, it has been shown that Chinese children tend to report more sleep problems than their US counterparts.34

The prevalence of insomnia symptoms in adolescents (9.1% for boys and 12.2% for girls) at post-pubertal stage is very similar to that of local adult prevalence rate using a similar definition of insomnia symptoms (9.7% for men and 12.8% for women).1,35 In other words, puberty is also a critical phase for the development of insomnia symptoms in both boys and girls. As puberty is associated with progressive changes in sleep physiology including decreased slow wave sleep and circadian delay,16,36 additional study is needed to investigate and clarify the interactions of homeostatic sleep change, circadian delay and pubertal development in predisposing vulnerable adolescents to the development of hyperarousal mechanism of insomnia.

Previous studies have reported a significant female preponderance for the risk of developing insomnia symptoms in adolescents,3,19,37 but the onset of sex differences in insomnia symptoms was unclear. Our study, with the detailed assessments of insomnia symptoms (including both subtypes and severity) and Tanner stage in both children and adolescents, clearly showed that the onset of sex differences in insomnia symptoms was significantly associated with the pubertal maturation, particularly at late puberty and post-puberty. The mechanisms underlying the role of puberty in leading to sex differences in insomnia symptoms are unclear. Several explanations may be possible. First, it has been shown that adolescent girls experience more stressors than adolescent boys.38 In addition, girls demonstrated more stress reactivity and depressive symptoms than boys even under the same stress level.39 As stressful life events are a major risk factor of insomnia symptoms in adolescents,40 higher stress level and more emotional reactivity to stressors in female adolescents may account for the sex differences in insomnia symptoms. Second, puberty-related sex differences in stress hormones may be another contributing factor. Previous studies found that the sex differences in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity starts to be more pronounced with the pubertal maturation.41,42 Given the links between insomnia and increased HPA axis activity upon awakening in middle-aged adults and adolescents at late puberty in our previous study,8 the changes of HPA axis activity across different stages of puberty may be a key mechanism underlying the puberty-related onset of female preponderance in insomnia. Third, the fluctuating ovarian hormones across menstrual cycle in girls at late puberty/post-puberty may also account for the sex differences in insomnia symptoms.18 From the perspective of brain maturation, Campbell et al.43 demonstrated that female adolescents have an earlier age of onset in the decline of delta power, a marker of brain maturation and sleep homeostasis, than male adolescents.

Interestingly, we did not find any significant sex differences in the association between Tanner stage and EMA subtype, albeit there was a trend of increasing report of EMA with the pubertal maturation. Previous meta-analysis has suggested that the sex differences in EMA is much weaker than those in DIS and DMS.44 The insignificant sex differences in EMA found in the current study may be due to the limited statistical power as related to the relatively low prevalence of EMA in adolescents. The possibility of intrinsic circadian delay in adolescents may also potentially contribute to the low prevalence of EMA as well as a delay in the emergence of sex differences in EMA, for example, in young or middle adulthood.

In keeping with previous studies,3,4,17–19,45 we found that insomnia symptoms were associated with a wide range of health-related correlates, including maladaptive lifestyles, behavioral problems, and poor mental and general health,46 which are independent of the pubertal status. There were also some sex differences in the association of insomnia symptoms with various health-related outcomes. Boys with insomnia seemed to consume more alcohol and energy drinks and were more likely to smoke, whereas girls with insomnia were much more vulnerable to emotional and relationship difficulties. We have also previously shown that insomnia symptoms moderate the sex differences in pain perception and somatic symptom complaints in middle-aged adults and adolescents.7 These studies suggest that insomnia leads to maladapted lifestyle practice in boys but mood and behavioral difficulties in girls.

Clinical Implications

Our findings have important clinical implications for the understanding of pathophysiology and management of insomnia symptoms. Pubertal maturation was associated with an approximate threefold increase of the prevalence of insomnia symptoms with emerging female preponderance from childhood to adolescence. In view of a considerable persistence rate as well as pervasive health repercussions of insomnia symptoms in adolescents,1,18,22 our findings suggested that late childhood and adolescence represent a critical period for early intervention and prevention of insomnia. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered the first-line treatment of insomnia in adults.47 However, there are only a few clinical trials that examined the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in the child and adolescent populations.48,49 In addition, we have previously found that only approximately 10% of Hong Kong Chinese adolescents with insomnia symptoms have sought help from the health-care professionals for their sleep problems.50 Hence, there is a pressing need to investigate the safety and efficacy of various therapies for insomnia and to increase the accessibility of these therapies among child and adolescent populations. Preliminary findings have suggested that effective management of insomnia has an added benefit of improving mental health outcomes in adolescents.51

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study was a large community-based sample including both children and adolescents, with detailed measures on sleep and pubertal status. However, some limitations were noted. First, the measure of pubertal status was based on the self-reported maturity of sex characteristics without the examination by a physician or hormonal evaluation. Nonetheless, self-assessment of Tanner stage has an excellent agreement with the rater-rated assessment in local Chinese adolescents,28 and is deemed acceptable in large-scale epidemiologic studies.52 Second, the determinations of insomnia symptoms were based on the self-report for secondary school adolescents and the parental report for primary school-age children.10 Although most well-validated questionnaire assessment of sleep problems in children are based on parental reports,53 parents were found to underestimate the prevalence of insomnia symptoms of their children.10 The lower prevalence of insomnia in children in the current study may be partially accounted by this issue. In addition, parents may not be fully aware of their child's distress or worry about the sleep disturbances (as described in the ISI), although we purposefully advised the key informant to consult and discuss with other relevant family member(s) so as to improve the accuracy of the report of sleep symptoms. Future research on the assessment of insomnia in children may be facilitated by the use of child-orientated format (e.g., with graphic illustration) in the assessment, such as the Children's Sleep Comic,54 and/or individual interview. Some aspects (e.g., general mental health as assessed by the GHQ-12) were only measured in the secondary school students as these measures were only validated in adolescents. Third, the nature of cross-sectional design in the current study did not allow for delineating the cause-effect relationship between insomnia and the health-related correlates. Fourth, there may be some response bias (e.g., more girls and older participants), but all the analyses were weighted for age and sex according to the census data in Hong Kong school-aged children and adolescents. Finally, all outcome measures in the current study relied on the self-reported or parent-reported questionnaires. Further studies with objective measures on sleep and puberty as well as other covariates (e.g., hormones, stress, and metabolic markers) are warranted to replicate the overall findings of the emergence of sex differences in insomnia in puberty.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Funding source: This project was supported by Public Policy Research of University Grants Committee (Reference number: CUHK4012-PPR-11), Hong Kong SAR, China. The funding body has no role in conception, design, conduction, interpretation, and analysis of the study or in the approval of the publication. Dr. Wing has received sponsorship from Lundbeck Export A/S, Servier Hong Kong Ltd, Pfizer Company Ltd, and Celki Medical Company. Dr. Kong has received honorarium for consultancy or giving lectures from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli-Lilly, Merck Serono, and Nestle. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang J, Li AM, Kong AP, Lai KY, Tang NL, Wing YK. A community-based study of insomnia in Hong Kong Chinese children: prevalence, risk factors and familial aggregation. Sleep Med. 2009;10:1040–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patten CA, Choi WS, Gillin JC, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E23. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blank M, Zhang J, Lamers F, Taylor AD, Hickie IB, Merikangas KR. Health correlates of insomnia symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Sleep. 2015;38:197–204. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohayon MM, Roberts RE, Zulley J, Smirne S, Priest RG. Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1549–56. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, Otte A, Perlis ML, Spiegelhalder K. The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:547–58. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309:706–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, et al. Insomnia, sleep quality, pain, and somatic symptoms: sex differences and shared genetic components. Pain. 2012;153:666–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, et al. A community-based study on the association between insomnia and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: sex and pubertal influences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:2277–87. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruno RM, Palagini L, Gemignani A, et al. Poor sleep quality and resistant hypertension. Sleep Med. 2013;14:1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fricke-Oerkermann L, Pluck J, Schredl M, et al. Prevalence and course of sleep problems in childhood. Sleep. 2007;30:1371–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neveus T, Cnattingius S, Olsson U, Hetta J. Sleep habits and sleep problems among a community sample of schoolchildren. Acta Paediatrica. 2001;90:1450–5. doi: 10.1080/08035250152708888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mong JA, Baker FC, Mahoney MM, et al. Sleep, rhythms, and the endocrine brain: influence of sex and gonadal hormones. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16107–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4175-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knutson KL. The association between pubertal status and sleep duration and quality among a nationally representative sample of U. S. adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2005;17:418–24. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, Breslau N. Epidemiology of DSMIV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e247–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun SL, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in a general population sample of young children and preadolescents: gender effects. Sleep Med. 2014;15:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagenauer MH, Perryman JI, Lee TM, Carskadon MA. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:276–84. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson EO, Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Trouble sleeping and anxiety/ depression in childhood. Psychiatry Res. 2000;94:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, Li AM, Lai KY, Wing YK. Longitudinal course and outcome of chronic insomnia in Hong Kong Chinese children: a 5-year follow-up study of a community-based cohort. Sleep. 2011;34:1395–402. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chan W. Persistence and change in symptoms of insomnia among adolescents. Sleep. 2008;31:177–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Lau JY, Dahl RE, Eley TC. The direction of longitudinal associations between sleep problems and depression symptoms: a study of twins aged 8 and 10 years. Sleep. 2009;32:189–99. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wing YK, Chan NY, Man Yu MW, et al. A school-based sleep education program for adolescents: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e635–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung KF, Kan KK, Yeung WF. Assessing insomnia in adolescents: comparison of Insomnia Severity Index, Athens Insomnia Scale and Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med. 2011;12:463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Growth and physiological development during adolescence. Annu Rev Med. 1968;19:283–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.19.020168.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang KS, Ng PN, Lee MM, Chan SJ. Sexual maturation of chinese boys in Hong Kong. Pediatrics. 1966;37:804–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MM, Chang KS, Chan MM. Sexual maturation of Chinese girls in Hong Kong. Pediatrics. 1963;32:389–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan NP, Sung RY, Kong AP, Goggins WB, So HK, Nelson EA. Reliability of pubertal self-assessment in Hong Kong Chinese children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44:353–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan DW, Chan TS. Reliability, validity and the structure of the General Health Questionnaire in a Chinese context. Psychol Med. 1983;13:363–71. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li WH, Chung JO, Chui MM, Chan PS. Factorial structure of the Chinese version of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire in adolescents. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:3253–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong MY, Wilkinson G. Validation of 30- and 12-item versions of the Chinese Health Questionnaire (CHQ) in patients admitted for general health screening. Psychol Med. 1989;19:495–505. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700012526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai KY, Luk ES, Leung PW, Wong AS, Law L, Ho K. Validation of the Chinese version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:1179–86. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao S, Zhang C, Zhu X, Jing X, McWhinnie CM, Abela JR. Measuring adolescent psychopathology: psychometric properties of the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire in a sample of Chinese adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Liu L, Owens JA, Kaplan DL. Sleep patterns and sleep problems among schoolchildren in the United States and China. Pediatrics. 2005;115:241–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li RH, Wing YK, Ho SC, Fong SY. Gender differences in insomnia--a study in the Hong Kong Chinese population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:601–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:521–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivertsen B, Harvey AG, Lundervold AJ, Hysing M. Sleep problems and depression in adolescence: results from a large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16-18 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:681–9. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0502-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ge XJ, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of Stressful Life Events and Depressive Symptoms during Adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:467–83. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Dev. 2007;78:279–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo C, Zhang J, Pan J. One-year course and effects of insomnia in rural Chinese adolescents. Sleep. 2013;36:377–84. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stroud LR, Papandonatos GD, Williamson DE, Dahl RE. Sex differences in cortisol response to corticotropin releasing hormone challenge over puberty: Pittsburgh Pediatric Neurobehavioral Studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1226–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wudy SA, Hartmann MF, Remer T. Sexual dimorphism in cortisol secretion starts after age 10 in healthy children: urinary cortisol metabolite excretion rates during growth. American journal of physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E970–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00495.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell IG, Grimm KJ, de Bie E, Feinberg I. Sex, puberty, and the timing of sleep EEG measured adolescent brain maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5740–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120860109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang B, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29:85–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Dahl RE, McGuffin P, Eley TC. Associations between sleep problems, anxiety, and depression in twins at 8 years of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1124–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owens JA, Mindell J, Baylor A. Effect of energy drink and caffeinated beverage consumption on sleep, mood, and performance in children and adolescents. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(Suppl 1):65–71. doi: 10.1111/nure.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morin CM. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to the treatment of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 16):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Bruin EJ, Oort FJ, Bogels SM, Meijer AM. Efficacy of internet and group-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adolescents: a pilot study. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12:235–54. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.784703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Bruin EJ, Bogels SM, Oort FJ, Meijer AM. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial with internet therapy, group therapy and a waiting list condition. Sleep. 2015;38:1913–26. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, Zhang J, Lam SP, et al. Help-seeking behaviors for insomnia in Hong Kong Chinese: a community-based study. Sleep Med. 2016;21:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clarke G, Harvey AG. The complex role of sleep in adolescent depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:385–400. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rasmussen AR, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Tefre de Renzy-Martin K, et al. Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation. Pediatrics. 2015;135:86–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23:1043–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwerdtle B, Kanis J, Kubler A, Schlarb AA. The Children's Sleep Comic: psychometrics of a self-rating instrument for childhood insomnia. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]