Abstract

Purpose

Our goal was to determine if there are differences by place of residence in visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant in a population-based study.

Methods

Using data from the Furthering Understanding of Cancer, Health, and Survivorship in Adult (FUCHSIA) Women’s Study, a cohort study of fertility outcomes in reproductive-aged women in Georgia, we fit models to estimate the association between geographic type of residence and seeking help for becoming pregnant.

Findings

The prevalence of visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant ranged from 13%-17% across geographic groups. Women living in suburban counties were most likely to seek medical care for help getting pregnant compared with women living in urbanized counties (adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) = 1.14, 95% CI: 0.74-1.75); among women who reported infertility this difference was more pronounced (aPR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.00-2.53). Women living in rural counties were equally likely to seek fertility care compared with women in urbanized counties in the full sample and among women who experienced infertility.

Conclusions

Women living in urban and rural counties were least likely to seek infertility care, suggesting that factors including but not limited to physical proximity to providers are influencing utilization of this type of care. Increased communication about reproductive goals and infertility care available to meet these goals by providers who women see for regular care may help address these barriers.

Keywords: access to care, geographic disparities, infertility, fertility care, utilization of health services

The ability to have a biological child is important to many women of childbearing age, and experiencing infertility can lead to a decreased quality of life.1 Most women have the expectation that they will be able to have a child at the time they decide to start a family, and when obstacles to meeting this goal are presented it can affect their mental health status as well as the health of their relationship with their partner.1 Infertility counseling and treatment may help some women become pregnant who are unable to conceive. Although medical care for infertile women encompasses a wide range of services, much of the literature on tracking infertility service use to date has focused on use of in vitro fertilization (IVF).2,3 Less is known about geographic differences in overall medical care for infertility, which includes IVF but also includes counseling and less invasive procedures such as use of medications to stimulate ovulation. According to the National Survey for Family Growth (NSFG), 17% of reproductive-aged women in the United States reported ever using an infertility service from 2006-2010.4 Among these women, advice and infertility testing were the most commonly reported services used.4

There has been an overall increase in the use of infertility care since 1982 when the NSFG began collecting this information, yet not all women who need medical help to become pregnant are getting the assistance they need. Underutilization of infertility services may be a result of many factors, including discomfort with certain procedures, high cost, and lack of awareness of the range of options available.5-7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released a National Public Health Action Plan to address the detection, prevention, and management of infertility; one of its objectives is to eliminate disparities in access to treatment for infertility.8 Where a woman lives may be a factor contributing to these disparities.

There are several documented barriers to accessing medical care in rural areas. These areas often have fewer health care providers per 100,000 population compared with urban areas.9 This limits the number of providers to choose from overall, as well as those trained in specialized reproductive care, which is necessary to provide some of the more intense therapies.9-11 Rural areas also have low population density, which often results in longer travel times to visit a doctor, increasing the time commitment needed to seek medical care.12 For example, most women living in areas of the country that are highly urbanized are within 60 minutes of a fertility clinic, while women living in more sparsely populated areas have longer travel times to reach specialized fertility care.3 Further, rural residence is also associated with lack of insurance or insurance instability, which may limit women’s ability to seek care. Even with insurance, many treatments are not covered.13-15 At the population level, insurance coverage affects women’s use of fertility counseling and treatment. In states where there is mandated insurance coverage for infertility care, rates of use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) have increased more rapidly than in states without mandates. However, in some subgroups, including black women, women with less education, and women with lower income, ART use remains low.15,16 The combination of both physical and financial barriers makes accessing medical care in some rural and remote areas challenging.

Little is known about differences by geographic type of residence in seeking medical advice and treatment for infertility. In this paper, we seek to determine if geographic disparities exist in visiting a doctor for help becoming pregnant among a population-based sample of reproductive-aged women in Georgia. The objectives of this study are to assess the overall association between the level of urbanization of the county where a woman lives and seeking fertility care or counseling and to describe differences in the type of provider accessed and infertility service utilized.

Methods

We used data from the Furthering Understanding of Cancer Health and Survivorship in Adult (FUCHSIA) Women’s Study, a population-based cohort study of fertility outcomes in cancer survivors in Georgia. Cancer survivors were recruited in collaboration with the Georgia Cancer Registry, a statewide, population-based registry that collects information on all reportable cancers in Georgia residents. Eligible cancer survivors were diagnosed with any malignant cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ between the ages of 20 and 35 years and at least 2 years prior to recruitment. Comparison women were identified using a purchased marketing list that was frequency matched on 5-year age groups and Georgia region of residence to eligible cancer survivors. Analyses for this paper utilized data from all of the comparison women from this larger study. These women had similar demographic characteristics to the participating cancer survivors and were intended to represent the general population. Women were eligible to participate if they were 22-45 years old at recruitment, had a working telephone, and spoke English. They were recruited independent of their fertility status. Women consented to participate and completed the study interview by telephone.17 The study was approved by the Emory University and Georgia Department of Public Health Institutional Review Boards.

Geographic type of residence was defined based on the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Urban-Rural Classification Scheme.18 This classification scheme categorizes counties into 1 of 6 groups based on level of urbanization. These groups include: (1) large central metropolitan, for counties with at least 1 million residents that also contain the largest principal city of the metropolitan statistical area (MSA), have their entire population contained in the largest principal city of the MSA, or have at least 250,000 people in any principal city in the MSA; (2) large fringe metropolitan, for counties that have at least 1 million residents, but do not meet the additional criteria for large central; (3) medium metropolitan, for counties in an MSA with populations between 250,000 and 999,999 residents; (4) small metropolitan, for counties in an MSA that have less than 250,000 residents; (5) micropolitan for counties that have between 10,000 and 49,999 residents; and (6) noncore for counties smaller than a micropolitan area.

For this study, a participant’s home address at the time of the interview was used to determine the level of urbanization of the participant’s residence. The 6-level NCHS scheme was collapsed to create a new classification scheme (Supplemental Figure 1, available online only). The first 2 categories were maintained from the original scheme (large central and large fringe), but they are referred to in this paper as urbanized and suburban counties, respectively. The third category combined medium and small metropolitan counties into one group, small metropolitan. The fourth category encompassed all non-metropolitan counties to form a small town/rural category. The outcome for this study was defined directly from a question on the study interview which asked “Have you ever visited a doctor or health professional for help becoming pregnant?” This question was asked of all participants regardless of marital status or reported infertility.

The interview also contained questions that allowed us to capture information on the characteristics of the study participants including race, current level of education, insurance, and total household income in the previous 12 months. Women reported if they had any experience with infertility and the ages at which it occurred. Infertility was defined as reporting a period of time lasting 12 months or longer between the ages of 20 and 34 years or a period of 6 months or longer at age 35 years or older when they had unprotected intercourse with a man at least 3 times per month, but did not get pregnant. This definition is similar to that of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, although their definition also includes that unprotected intercourse must be appropriately timed.19 While we did not restrict on appropriate timing to classify women as experiencing infertility, we did ask whether or not women were actively trying to get pregnant, which we used to determine pregnancy intention during the time they were having unprotected intercourse and not getting pregnant. To capture some of the cultural aspects that may be affecting women’s decision-making, women were asked their feelings about adoption, use of invasive infertility treatments, and importance of having a biological child using a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Data Analysis

SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for all statistical analyses. We examined participant characteristics by county geographic category and by visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant. Among those visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant, we also described type of doctor visited and type of infertility service used. Log binomial models were fit to estimate a prevalence ratio (PR) for visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant for each of the county of residence classification schemes. Modified Poisson regression with robust variances was used in cases where the log binomial model did not converge.20 Models were fit for both the total population and restricted to women who reported ever experiencing infertility, because this subgroup is most likely to need to visit a doctor for fertility counseling and treatment. The prevalence of visiting a doctor among participants from suburban, small metropolitan, and small town/rural counties were each compared with visiting a doctor among participants from an urbanized county. A similar analysis was conducted using data from the 2006-2010 cycle of the NSFG to compare the results from our study with national estimates.

Based on the literature and a causal diagram created for this study, we determined important covariates of the association between place of residence and visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant. The first set of models controlled for race (black, white, other race), education (college or greater, less than college degree) and income (less than $50k, $50-$100k, $100k+). These demographic factors were hypothesized as confounders of the association being evaluated. In the second set of models, we additionally controlled for other covariates we hypothesized might differ by place of residence, including women’s comfort with ART and adoption, how important it was to have a biological child, insurance status (private, public, self, none), and among the subgroup who reported a period of infertility, age at infertility and whether or not women were actively trying to get pregnant during this period.

Results

For this study 1,073 women were included in the analysis. Median age at interview was between 38 and 39 years across county geographic categories (Table 1). We had good representation by race in the overall study population, although when we stratified by our exposure we found less racial diversity in the small town/rural and small metropolitan counties, which is consistent with state demographics.21 Participants from urbanized counties were most likely to have at least a college degree and had the highest household incomes of the 4 county geographic categories. Small town/rural and small metropolitan counties had the most uninsured and publicly insured women. The majority of women, regardless of residence, did not know if their insurance policy covered fertility treatment (small town/rural: 72.6%, small metropolitan: 65.5%, suburban: 70.0%, urbanized: 71.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants by 4 County-Level Categories of Urbanization

| Type of county | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Small town/rural (n = 113) |

Small metropolitan (n = 171) |

Suburban (n = 655) |

Urbanized (n = 134) |

Total (n = 1073) |

|

|

| |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age at interview (years) |

|||||

| 22-29 | 12 (10.6) | 14 (8.2) | 36 (5.5) | 10 (7.5) | 72 (6.7) |

| 30-39 | 66 (58.4) | 87 (50.9) | 355 (54.2) | 68 (50.8) | 576 (53.7) |

| 40-45 | 35 (31.0) | 70 (40.9) | 264 (40.3) | 56 (41.8) | 425 (39.6) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 94 (83.2) | 121 (70.8) | 419 (64.5) | 78 (59.1) | 712 (66.8) |

| Black | 16 (14.2) | 40 (23.4) | 203 (31.2) | 50 (37.9) | 309 (29.0) |

| Other race | 3 (2.7) | 10 (5.9) | 28 (4.3) | 4 (3.0) | 45 (4.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Education | |||||

| High school and less |

10 (8.9) | 13 (7.6) | 26 (4.0) | 3 (2.3) | 52 (4.9) |

| Some college | 43 (38.1) | 50 (29.2) | 151 (23.1) | 13 (9.8) | 257 (24.0) |

| College graduate | 30 (26.6) | 55 (32.2) | 250 (38.2) | 61 (45.9) | 396 (36.9) |

| Graduate school | 30 (26.6) | 53 (31.0) | 228 (34.8) | 56 (42.1) | 367 (34.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Income | |||||

| Less than $50k | 56 (50.9) | 60 (35.5) | 159 (24.7) | 24 (18.5) | 299 (28.4) |

| $50k - 100k | 40 (36.4) | 69 (40.8) | 252 (39.1) | 41 (31.5) | 402 (38.2) |

| $100k+ | 14 (12.7) | 40 (23.7) | 233 (36.2) | 65 (50.0) | 352 (33.4) |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 20 |

| Insurancea | |||||

| Private | 86 (76.1) | 128 (74.9) | 536 (82.0) | 109 (82.0) | 859 (80.2) |

| Public | 5 (4.4) | 11 (6.4) | 14 (2.1) | 2 (1.5) | 32 (3.0) |

| Self-insured | 4 (3.5) | 9 (5.3) | 44 (6.7) | 11 (8.3) | 68 (6.4) |

| None | 18 (15.9) | 23 (13.5) | 60 (9.2) | 11 (8.3) | 112 (10.5) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Visited a doctor for help getting pregnant |

|||||

| Yes | 15 (13.3) | 24 (14.0) | 112 (17.1) | 20 (14.9) | 171 (15.9) |

| No | 98 (86.7) | 147 (86.0) | 543 (82.9) | 114 (85.1) | 902 (84.1) |

| Experienced infertilityb |

|||||

| Yes | 39 (36.8) | 46 (27.7) | 177 (28.3) | 27 (20.6) | 289 (28.1) |

| No | 67 (63.2) | 120 (72.3) | 449 (71.7) | 104 (79.4) | 740 (71.9) |

| Missing | 7 | 5 | 29 | 3 | 44 |

| Age at infertility Median years (IQR) |

25 (22, 29) | 26 (24, 29) | 27 (23, 30) | 28 (26, 31) | 27 (23, 30) |

| Actively tryingc | |||||

| Yes | 23 (59.0) | 29 (63.0) | 97 (54.8) | 16 (59.3) | 165 (57.1) |

| No | 16 (41.0) | 17 (37.0) | 80 (45.2) | 11 (40.7) | 124 (42.9) |

Insurance: Private insurance includes insurance provided by the participant’s employer or school, partner or parents, and military or Veteran’s Affairs insurance; public insurance includes Medicaid and Medicare.

Infertility: A period of time lasting at least 6 months at or after age 35 years or at least 12 months between the ages of 20 and 34 years when a woman was having regular unprotected intercourse, but she did not get pregnant.

Actively trying to get pregnant during the reported infertile period.

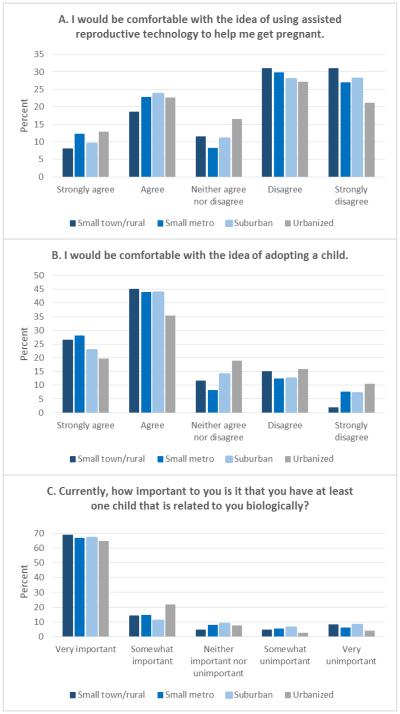

Reports of infertility were highest in small town/rural counties (36.8%) and lowest in urbanized counties (20.6%). Median age at infertility ranged from 25 to 28 years old across the 4 groups. Compared with women living in urbanized counties, women from small town/rural counties reported less comfort with ART but greater comfort with adoption (Figures 1a, 1b). The importance of having a biological child was similar across all 4 geographic categories, with most women reporting that this was very important to them (Figure 1c). The crude proportion of women ever visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant ranged from 13% in the small town/rural counties to 17% in the suburban counties, which is consistent with the national average of 15% among 22- to 44-year-old female participants in the 2006-2010 NSFG.

Figure 1.

(A-C). Feelings about Biologic Children, Assisted Reproductive Technology, and Adoption by Four Category County Level of Urbanization

Among women who visited a doctor for help getting pregnant, women in small town/rural counties reported doing so at younger ages (median 27 years, interquartile range (IQR) 24, 30) compared with women from urbanized counties who reported older ages (median 30.5 years, IQR: 27, 35) (Table 2). Many women saw more than one type of health care provider, which in most cases included visiting their obstetrician/gynecologist. Sixty percent of women from urbanized counties reported visiting a fertility specialist, compared with 33% in small town/rural counties. Residents of urbanized and suburban counties combined also reported more use of alternative medicine, with 14% reporting a visit to an acupuncturist or naturopath compared with 5% among small town/rural and small metropolitan residents, combined.

Table 2.

Characteristics for Doctor Visits for Women Seeking Help in Getting Pregnant by 4 County-Level Categories of Urbanization

| Type of county | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Small town/ rural (n = 15) |

Small metropolitan (n = 24 ) |

Suburban (n = 112 ) |

Urbanized (n = 20) |

Total (n = 171 ) |

|

|

| |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age at visita | |||||

| Median | 27 | 29.5 | 30 | 30.5 | 30 |

| (IQR) | (24, 30) | (27, 32) | (27, 34) | (27, 35) | (27, 33) |

| Type of doctorb | |||||

| General practitioner | 1 (6.7) | 5 (20.8) | 14 (12.5) | 2 (10.0) | 22 (12.9) |

| Obstetrician/ gynecologist | 15 (100.0) | 24 (100.0) | 99 (88.4) | 16 (80.0) | 154 (90.1) |

| Fertility specialist | 5 (33.3) | 11 (45.8) | 53 (47.3) | 12 (60.0) | 81 (47.4) |

| Acupuncturist/ naturopath | 1 (6.7) | 1 (4.2) | 15 (13.4) | 3 (15.0) | 20 (11.7) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.8) |

| Type of treatmentc | |||||

| None | 2 (13.3) | 3 (12.5) | 16 (14.3) | 3 (15.0) | 24 (14.0) |

| Testing only | 1 (6.7) | 4 (16.7) | 27 (24.1) | 6 (30.0) | 38 (22.2) |

| Surgery | 4 (26.7) | 2 (8.3) | 21 (18.8) | 5 (25.0) | 32 (18.7) |

| Medications | 10 (66.7) | 16 (66.7) | 56 (50.0) | 8 (40.0) | 90 (52.6) |

| Insemination | 3 (20.0) | 4 (16.7) | 26 (23.2) | 5 (25.0) | 38 (22.2) |

| IVFd | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.5) | 17 (15.2) | 4 (20.0) | 24 (14.0) |

Two women were missing age at visit.

Women could report visiting more than one doctor.

No treatment and testing only were mutually exclusive with the other categories of treatment, but women could report more than one treatment that involved surgery, medications, insemination, or IVF.

in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempt, not success

Type of treatment received also differed by place of residence. Women from small town/rural and small metropolitan counties were more likely than those from urbanized or suburban counties to receive medications, but they were less likely to receive testing alone or IVF. Participants who lived in small town/rural and urbanized counties reported surgery more than the other 2 groups. Women who reported receiving the most invasive treatment procedure, IVF, differed by type of county of residence, with 20% of women from urbanized, 15.2% from suburban, 12.5% from small metropolitan, and no women from small town/rural counties reporting receipt of this treatment modality.

Unadjusted estimates for visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant showed women residing in small town/rural counties were less likely (PR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.48-1.65) and women living in a suburban county were more likely (PR = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.74-1.78) to visit a doctor compared with women living in an urbanized county. The prevalence ratio comparing women from a small metropolitan county to women from an urbanized county showed no differences (PR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.54-1.63) (Table 3). In adjusted estimates, seeking fertility care among women from small metropolitan and small town/rural counties was similar to that of urbanized counties. However, women living in suburban counties remained slightly more likely to visit a doctor compared with women from urbanized counties in all adjusted analyses.

Table 3.

Crude and Adjusted Odds ratios of the Association Between 4 County-Level Categories of Urbanization and Visiting a Doctor for Help Getting Pregnant

| Visited a doctor for help getting pregnant | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unadjusted | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|

| ||||||

| PR | 95%CI | PR | 95%CI | PR | 95%CI | |

| All Women | ||||||

| Urbanized | reference | reference | Reference | |||

| Suburban | 1.15 | 0.74-1.78 | 1.16 | 0.75-1.80 | 1.14 | 0.74-1.75 |

| Small metropolitan | 0.94 | 0.54-1.63 | 1.05 | 0.60-1.81 | 1.04 | 0.60-1.79 |

| Small town/rural | 0.89 | 0.48-1.65 | 1.02 | 0.54-1.94 | 1.09 | 0.57-2.09 |

| Women who experienced infertility |

||||||

| Urbanized | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Suburban | 1.30 | 0.77-2.17 | 1.49 | 0.93-2.40 | 1.59 | 1.00-2.53 |

| Small metropolitan | 1.06 | 0.57-1.94 | 1.30 | 0.74-2.27 | 1.36 | 0.80-2.30 |

| Small town/rural | 0.76 | 0.38-1.54 | 0.90 | 0.45-1.78 | 1.09 | 0.55-2.17 |

Adjusted for: education (less than college degree vs college degree or greater), income (less than $50k, $50-100k, $100k+), race (black, white, other)

Adjusted for: covariates in model 1 + comfort with assisted reproductive technology (yes/no), comfort with adoption (yes/no), biological child (important/unimportant), insurance status (private, public, self, none); models among women who experienced infertility also include age at infertility (20’s, 30’s, 40’s) and whether or not women were actively trying to get pregnant at the time of infertility

When restricted to women experiencing infertility, there was a similar crude association as in the full sample. Small town/rural county residents were less likely and suburban county residents were more likely to visit a doctor for help getting pregnant (PR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.38-1.54 and PR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.77-2.17, respectively), and there was no difference between small metropolitan county residents and urbanized county residents (PR = 1.06, 95% CI: 0.57-1.94). After adjusting for covariates in this subgroup, there was a stronger association than in the full sample between visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant for women living in a suburban county compared with women living in an urbanized county (Model 1, adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) = 1.49, 95% CI: 0.93-2.40 and Model 2, aPR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.00-2.53). Unlike models fit with the entire population, women from a small metropolitan county showed an increased likelihood of visiting a doctor similar to that of the suburban residing participants (Model 1, aPR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.74-2.27 and Model 2, aPR = 1.36, 95% CI: 0.80-2.30). Adjusted estimates comparing small town/rural residents with urbanized county residents were null.

We were able to compare our results with the NSFG, although the classification of place of residence was not identical (Supplemental Table 1, available online only). After adjustment for confounders (race, education and income) women in small metropolitan and suburban areas (MSA, other) were more likely to seek fertility care or counseling compared with those living in large central cities (MSA, central city) (aPR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12-1.53). In addition, women living in small town and rural areas (Not MSA) were also more likely to seek fertility care or counseling compared with women in large central cities (aPR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.15-1.71). In the NSFG, infertility was defined as having intercourse without contraception and without a pregnancy in the past 12 months and measured in married and cohabitating women. Using this definition, 9.2% of women in the NSFG experienced infertility, after excluding women who were themselves or had partners who were surgically sterile. Results from models among the subgroup of women with infertility were similar to those in the full sample.

Discussion

This large population-based study provides critical information about the relationship between women’s access to fertility-related counseling and treatment and the level of urbanization of the county where they live. Among the full sample and women with infertility, living in a suburban county was associated with a greater likelihood of visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant compared with living in an urbanized county. The most notable differences were among the women who reported experiencing infertility. After accounting for differences in the distribution of participant characteristics by type of residence, women who experienced infertility from small town counties became similar to the women from suburban counties in their use of medical care for help getting pregnant, and small town/rural residents became more similar to urbanized county residents. In our NSFG analysis women from suburban areas and small town/rural areas were more likely to visit a doctor for fertility care compared with women from a large central city. This result differs from what we found in our study, but it may be a result of differences in geographic categories between studies, study populations (Georgia vs United States), or heterogeneity in urban and rural contexts depending on region of the country.

Limited access to certain specialists may constrain the range of treatment options women receive for help getting pregnant. Women living in small town/rural counties and small metropolitan counties were most likely to report receiving medications as part of their treatment, which may be a reflection of the type of health care provider they are seeing for care. Women living in these 2 types of places of residence all reported seeing their obstetrician/gynecologist for fertility care, who may have prescribed them medications, whereas IVF would require referral to a fertility specialist and visiting an ART clinic.

A strength of our study was that women were recruited to participate independently of their fertility status, allowing for a comparison between women who did and did not visit a doctor for help getting pregnant. This is an advantage over fertility clinic-based studies which are only able to describe women who seek help. All women interviewed were asked whether or not they ever visited a doctor for help getting pregnant, regardless of their marital or infertility status. Of those visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant, close to 10% never reported experiencing a period of infertility. Because the interview was extensively detailed, we were able to capture information not commonly collected in studies, such as women’s feelings about ART and adoption, as well as how important having a biological child was to them. These factors were used as indicators of cultural concerns, and they showed differences between geographic groups. Additionally, we had information on pregnancy intention which has been found in other studies to differ by race and education.22,23 This information was used to describe some of the cultural and environmental factors that may differ by type of county of residence.

The sample size overall for this study was large, but once women were divided into geographic categories, the sample size for each of these groups became small. The small sample within each category of our exposure variable caused many of our estimates to be imprecise; however, we focused on an issue that has been sparsely addressed in the literature. Studies looking at geographic disparities in use of medical help have focused on other health outcomes or access to only specialized care for becoming pregnant.3,24-26 Another limitation was that we were constrained to women’s place of residence at the time of the interview, which on average, was 9 years after the age at visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant. On the population level, there has been an approximately 3.5% increase in the urban population in the state of Georgia between 2000 and 2010.27,28 This shift in population towards urbanized counties means some women may be misclassified. However, even among women who did move they may have remained in the same type of county, so they would still be correctly classified.

This study adds to the literature on disparities in access to care for help getting pregnant. The population-based aspect of our study aligns with the CDC’s National Action Plan focused on addressing infertility and its treatment at the population level.8 Suburban county residents were consistently the most likely to visit a doctor for fertility counseling and treatment of the 4 categories of county level of urbanization, even after adjusting for education and income. Our results suggest that there may be limited differences in seeking medical care for help getting pregnant among small metropolitan county residents compared with suburban residents, after controlling for differences in the characteristics of women in these populations. This study also confirms that fewer women who live in small town/rural counties are accessing care for help getting pregnant compared to women living in other types of counties. Lastly, this study highlights a difference in a little explored comparison between residents within large metropolitan counties, with the urbanized counties being less likely to access infertility care compared with suburban residents. Larger population-based studies in a defined region could provide more precise estimates of geographic disparities in visiting a doctor for help getting pregnant to confirm the findings of this study. These studies could also provide information on factors driving low use of fertility care in urbanized counties that we found in our study, where physical access to care is not the major barrier. Rather, this disparity might be caused by financial or sociocultural barriers.

Although increasing the number of fertility specialists in small town/rural counties may not be possible, efforts can be made to provide more information about infertility care through general practitioners and obstetrician/gynecologists, from whom our study shows women living in small town/rural counties are most likely to seek fertility care or counseling. This strategy is also applicable to practitioners in urbanized counties where fertility specialists may be available but inaccessible for reasons other than physical access. An improved effort to communicate with patients about their reproductive goals and medical options available to meet these goals by less specialized health care providers may increase the use of medical care for help getting pregnant, allowing more women to achieve their desired family size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for this research was provided by The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1R01HD066059 and the Reproductive, Perinatal & Pediatric Training Grant T32HD052460; and by the Health Resources and Service Administration Training Grant T03MC07651-06.

References

- 1.Chachamovich JR, Chachamovich E, Ezer H, Fleck MP, Knauth D, Passos EP. Investigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: a systematic review. Journal of psychosomatic obstetrics and gynaecology. 2010;31(2):101–110. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2010.481337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Crawford S, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance -- United States, 2010. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002) 2013;62(9):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nangia AK, Likosky DS, Wang D. Access to assisted reproductive technology centers in the United States. Fertility and sterility. 2010;93(3):745–761. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982-2010. National health statistics reports. 2014;(73):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Missmer SA, Seifer DB, Jain T. Cultural factors contributing to health care disparities among patients with infertility in Midwestern United States. Fertility & Sterility. 2011;95(6):1943–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain T. Socioeconomic and racial disparities among infertility patients seeking care. Fertility & Sterility. 2006;85(4):876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers GM, Sullivan EA, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertility and sterility. 2009;91(6):2281–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Public Health Action Plan for the Dectection, Prevention, and Management of Infertility. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: Jun, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart LG, Salsberg E, Phillips DM, Lishner DM. Rural health care providers in the United States. J Rural Health. 2002;18(5):211–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doty B, Zuckerman R, Finlayson S, Jenkins P, Rieb N, Heneghan S. How does degree of rurality impact the provision of surgical services at rural hospitals? J Rural Health. 2008;24(3):306–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dis J. MSJAMA. Where we live: health care in rural vs urban America. Jama. 2002;287(1):108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelman MA, Menz BL. Selected comparisons and implications of a national rural and urban survey on health care access, demographics, and policy issues. J Rural Health. 1996;12(3):197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1996.tb00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields BE, Bell JF, Moyce S, Bigbee JL. The Impact of Insurance Instability on Health Service Utilization: Does Non metropolitan Residence Make a Difference? J Rural Health. 2015;31(1):27–34. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartley D, Quam L, Lurie N. Urban and rural differences in health insurance and access to care. J Rural Health. 1994;10(2):98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1994.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain T, Hornstein MD. Disparities in access to infertility services in a state with mandated insurance coverage. Fertility & Sterility. 2005;84(1):221–223. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henne MB, Bundorf MK. Insurance mandates and trends in infertility treatments. Fertility and sterility. 2008;89(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin HB, Johnson CY, Kim KH, et al. Piloting a computer assisted telephone interview: the FUCHSIA Women's Study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0149-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Vital and health statistics. Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research. 2014;(166):1–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicine PCotASfR Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertility & Sterility. 2013;99(1):63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. 2013 Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- 22.Greil AL, McQuillan J, Johnson K, Slauson-Blevins K, Shreffler KM. The hidden infertile: infertile women without pregnancy intent in the United States. Fertility & Sterility. 2010;93(6):2080–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. "It just happens": a qualitative study exploring low-income women's perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91(2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullen MT, Wiebe DJ, Bowman A, et al. Disparities in accessibility of certified primary stroke centers. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45(11):3381–3388. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens JM, Brotherton S, Dunning SC, et al. Geographic disparities in patient travel for dialysis in the United States. J Rural Health. 2013;29(4):339–348. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor A, Wellenius G. Rural-urban disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Public health. 2012;126(10):813–820. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Census Bureau . 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts, CPH-2-12, Georgia. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Census Bureau . 2000 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts PHC-3-12, Georgia. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.