Abstract

Macro-social/structural events (“big events”) such as wars, disasters, and large-scale changes in policies can affect HIV transmission by making risk behaviors more or less likely or by changing risk contexts. The purpose of this study was to develop new measures to investigate hypothesized pathways between macro-social changes and HIV transmission. We developed novel scales and indexes focused on topics including norms about sex and drug injecting under different conditions, involvement with social groups, helping others, and experiencing denial of dignity. We collected data from 300 people who inject drugs in New York City during 2012–2013. Most investigational measures showed evidence of validity (Pearson correlations with criterion variables range = 0.12–0.71) and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha range = 0.62–0.91). Research is needed in different contexts to evaluate whether these measures can be used to better understand HIV outbreaks and help improve social/structural HIV prevention intervention programs.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Big events, Structural interventions, Measures development

Introduction

Measurement is essential to science. This is evident in the role of telescopes in early astronomy and in the role of HIV antibody tests in understanding the epidemiology of this disease. New measures are essential for two related emerging needs in HIV prevention science. Public health researchers have come to realize that “big events” (described below) and social/structural interventions are important for efforts to control HIV, and that both of them may have contingent downstream effects on the extent of high-risk drug use and high-risk sex in a community. The purpose of this study was to develop new measures that reflect intermediary pathways between distal social/structural processes and proximal social contexts and individual behaviors that can put people at risk for exposure to HIV.

Structural interventions and social intervention models have been proposed as ways to reduce HIV transmission and outbreaks [1–8]. Social/structural interventions can have greater population-level effects than other kinds of interventions because they require less active participation by individuals [9]. Some structural interventions have shown great promise in reducing the risk of HIV and related infections. For example, establishment of legal syringe exchange programs in New York City (NYC) was followed by reduced syringe sharing and reduced HIV incidence among people who inject drugs (PWID) [10, 11]. Other structural HIV-prevention interventions that have been proposed include decriminalization of drug possession, decriminalization of sex work, providing housing for unstably housed people, and reducing the extent of structural racism [12, 13].

A macro-social phenomenon, big events, can also have intermediate effects on HIV epidemics [14]. Big events like wars, other political/economic crises, and natural disasters can increase the number of people who are HIV-infected or are susceptible to HIV infection by leading people to begin or increase their sexual and/or injection risk behavior, and by reshaping social networks so that more infected and uninfected people have sex or share injection syringes [15–17]. Such big events have been followed by HIV epidemics in the former Soviet Union, South Africa, Indonesia, Greece and other countries, but notably not yet in others, such as in Argentina or the Philippines [18–20]. These epidemics theoretically could have been prevented by interventions, for example, to increase consistent condom use among people exchanging sex for money; and/or by increasing the utilization of sterile syringes among drug injectors. In addition, if there were more complete measures of potential pathways by which changing social structural contexts lead populations to become susceptible (for example, by engaging in sex work or injecting drugs) or to increase their susceptibility (for example, by not using condoms consistently, or by sharing drug injection syringes or preparation equipment) then perhaps new types of effective HIV prevention intervention programs could be developed.

The major characteristic that big events and social/ structural interventions have in common for the purposes of this study is that both may have downstream effects that previously-existing measures could not assess. In addition, in some cases, efforts such as social movements might be required to implement such social/structural interventions such as greatly reducing the extent to which police and courts incarcerate racial minorities or to reduce or ending structural racism altogether.

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)

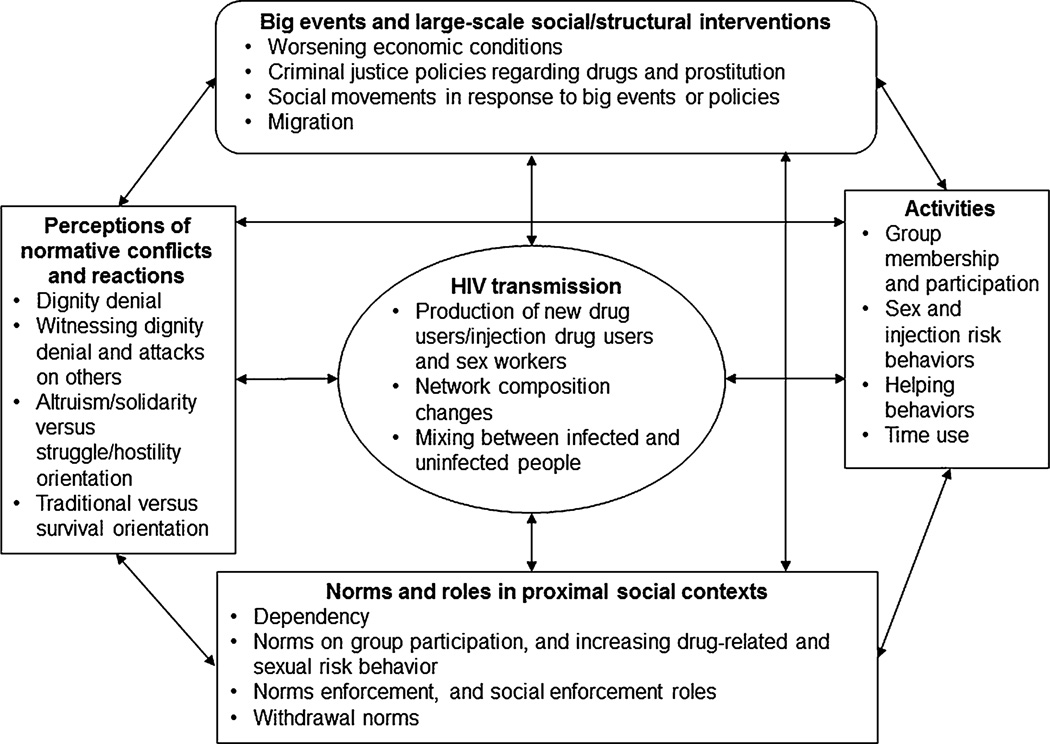

We have theorized that cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) can help us understand the pathways between structural interventions or big events and HIV epidemics [16, 18, 21, 22]. CHAT provides a framework within which to study the pathways from these macro-level changes to individuals’ risks. A model of these pathways categorized into CHAT domains is presented in Fig. 1. Both structural interventions and big events can change the daily lives of PWID and other people. CHAT focuses on changes in people’s activities—that is, what they do and the social contexts in which they do it; how these activities are associated with changes in the cultural norms and interpersonal interchanges that embody these norms; and the ways in which people think and change as these activities, norms and interchanges change. CHAT consists of three domains: (A) norms and roles in proximal social contexts; (B) activities; and (C) perceived micro-social conflicts and reactions. CHAT sees each of these domains as multi-faceted and as affecting and being affected by each of the other domains. For example, the structure of labor activities or employment (which are aspects of time use) helps to produce cultural norms and social exchanges. As a result of big events or perhaps structural interventions, the number of people working outside the home can change, and this can change various norms and how people’s selves react to the changes around them [23]. In essence, CHAT is a contextual theory positing that individuals may change their behaviors as they attempt to resolve conflicts between their previous behaviors (and cultural determinants of their previous behaviors) with new cultural and normative information. We use CHAT to encompass these dialectical processes to help understand how and why HIV risk behaviors and social network structures change.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of CHAT processes as pathways between big events or large-scale social/structural interventions and HIV transmission

Guided by CHAT, we used existing literature, and extensive qualitative research and pilot testing among adults in key risk populations in NYC—PWID, heterosexuals living in high poverty/high HIV prevalence areas (HET), and men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM), to develop self-reported responses to questionnaire items that we hypothesize represent pathways between macro-social changes and HIV risks [17, 18, 21, 22, 24–28]. (Pathways measures, organized by CHAT category are presented in Table 2, along with results. Individual items are presented in Online Appendix A). We developed a broad set of measures that could be used for studies of drug using and non-drug using populations. In some cases the new measures are similar to existing ones. For example, while measures of stigma regarding drug use or sexuality have been used previously in research, we developed new measures of experiences where dignity was denied (C1–C5, Table 2), sometimes referred to as “enacted stigma” [29, 30]. In other cases the new measures reflect factors that may be related to the development of risk behaviors that have not been studied previously quantitatively, such as intergenerational normative communication (C8 and C9, Table 2).

Table 2.

New potential pathways index and scale characteristics grouped by CHAT domain, and correlations with criterion variables or vignettes items

| CHAT domain scale/(index) | n | Number of items/categories |

Mean (standard deviation) |

Range | Scale Cronbach’ s alpha |

Correlation with criterion variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Norms and roles in proximal social contexts | ||||||

| A1. Norms on participating in group activities |

235 | 6 | 2.6 (0.64) | 2–6 | 0.89 | 0.31A |

| A2. Norms on increasing sexual risk behaviors |

297 | 6 | 1.2 (0.42) | 1–3 | 0.80 | 0.71B |

| A3. Norms on injectable drug behaviors |

296 | 4 | 1.5 (1.00) | 1–5 | 0.62 | 0.22C |

| A4. Rules at multi-partnered sex events | 48 | 10 | 2.0 (0.57) | 1–4 | 0.83 | 0.42D |

| A5. Sex norms enforcement at multi- partnered sex events |

48 | 4 | 3.2 (0.75) | 1.5–5 | 0.64 | 0.48D |

| A6. Sex rules at drug-using venues | 218 | 12 | 1.8 (0.83) | 1–4.1 | 0.83 | 0.38D |

| A7. Drug use norms, rules and roles at drug-using venues |

239 | 13 | 4.9 (1.6) | 1–7 | 0.91 | 0.54E |

| A8. Injection norms in the context of opiate withdrawal |

296 | 11 | 4.5 (0.60) | 2–5 | 0.90 | −0.44C |

| A9. Dependency on relatives | 297 | 8 | 17.3 (7.98) | 8–38 | 0.89 | −0.23F |

| A10. Dependency on friends | 297 | 7 | 11.9 (3.63) | 7–27 | 0.70 | −0.34F |

| A11. Dependency on service agencies | 296 | 8 | 17.7 (7.32) | 8–40 | 0.79 | 0.34G |

| B. Activities | ||||||

| B1. Involvement with formal social groups (index) |

300 | 33 | 1.0 (0.99) | 0–4 | - | −0.21H |

| B2. Involvement with informal social groups (index) |

300 | 13 | 0.3 (0.60) | 0–4 | - | 0.18H |

| B3. Frequency of helping others | 291 | 10 | 3.4 (0.55) | 2–5.4 | 0.79 | 0.13I |

| C. Perceived micro-social conflicts and reactions | ||||||

| C1. Dignity denial perpetrators (index) | 300 | 39 | 3.7 (2.71) | 0–14 | - | 0.42J |

| C2. Dignity denial characteristic targeting (index) |

300 | 25 | 4.0(3.11) | 0–24 | - | 0.50J |

| C3. Dignity denial reaction | 250 | 9 | 3.3 (0.71) | 2–5.3 | 0.77 | 0.50J |

| C4. Witnessing dignity denial perpetrators (index) |

300 | 39 | 4.4 (2.44) | 0–17 | - | 0.21J |

| C5. Witnessing dignity denial reaction | 294 | 4 | 3.3 (0.80) | 1.75–5.75 | 0.77 | 0.25L |

| C6. Witnessing verbal and physical attacks on others |

300 | 19 | 30.2 (9.15) | 19–71 | 0.89 | 0.14J |

| C7. Witnessing defense of, and assistance to, others |

300 | 10 | 15.4 (3.50) | 10–32 | 0.73 | 0.28I |

| C8. Intergenerational normative disjuncture (younger adults) |

18 | 8 | 2.8 (0.28) | 2.13–3 | 0.69 | 0.64B |

| C9. Intergenerational normative disjuncture (older adults) |

278 | 9 | 19.4 (4.98) | 9–27 | 0.91 | −0.12B |

| C10. Altruistic cultural orientation | 297 | 13 | 3.8 (0.70) | 2.23–5 | 0.91 | 0.48I |

| C11. Solidaristic cultural orientation | 297 | 9 | 3.6 (0.72) | 1.67–5 | 0.83 | 0.41I |

| C12. Struggle cultural orientation | 297 | 10 | 3.7 (0.87) | 1–5 | 0.91 | 0.44I |

| C13. Traditional cultural orientation | 297 | 16 | 2.6 (0.67) | 1–4.75 | 0.84 | −0.52M |

| C14. Competitiveness cultural orientation |

297 | 11 | 3.3 (0.89) | 1.27–5 | 0.87 | 0.70N |

| C15. Hostility cultural orientation | 297 | 9 | 2.4 (0.67) | 1–5 | 0.75 | 0.26O |

| C16. Survival cultural orientation | 297 | 11 | 3.6 (0.87) | 1.36–5 | 0.89 | 0.39I |

N = 300 people who inject drugs in New York City, 2012–2013

All correlations are significant at the p < 0.05 level. Criterion validity variables used in correlations were: number of groups involved with;

number of recent sex partners;

recently shared injection syringes;

used condoms consistently use at multi-partnered sex events;

attended a multi-partnered sex event in the last year;

income category;

positive HIV serostatus;

recently shared drug preparation equipment;

brought assistance to others in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy;

current homelessness;

Dignity Denial Perpetrators;

Witnessing Dignity Denial Perpetrators;

recently engaging in sex exchange for money, drugs or other goods;

vignettes item 1 (see Table 1);

veteran of the U.S. armed forces or reserves

Below we describe the qualitative and quantitative development of the new potential pathways measures, and present results of initial reliability and validity analyses.

Methods

Qualitative Development of the New Measures

We conducted extensive interviews with PWID, MSM, and HET in 2012–2014 to develop these measures. We conducted four focus groups, 18 in-depth interviews, and 17 pilot interviews to develop grounded understandings of each conceptual area for which measures were to be developed. The content of the items reflects the underlying constructs being measured by each scale or index. After initial concepts were developed, initial lists of candidate questions to measure them were drafted. In writing the items we drew on language used in in-depth interviews and focus groups to help word questions and response categories appropriately. We attempted to balance the need for nuanced information with the expected verbal skills of participants. We used feedback from in-depth interview participants and focus group participants, as well as from members of a scientific advisory board of experts on structural factors and HIV that we established as part of the study, to help us revise the questions. We adapted the formats and some language from our community-oriented roles measures to create measures for protective roles in group sex or drug-using events [31]. Our pathways measures are new, but in some cases extend or complement existing measures, e.g., of stigma and norms about condom use and partner selection [32–40].

Quantitative Development of the New Measures

Sample

We interviewed 300 PWID in the Lower East Side of Manhattan between November 29, 2012 and June 12, 2013, using referrals from a large study of PWID in NYC that used respondent driven sampling, and paid participants to refer others, and offered HIV counseling and testing. All participants were referred to us by the larger study; we paid no participants for referrals. Interviews were conducted face-to-face by two of the authors (MS and YJ), both with extensive experience interviewing PWID. We used paper and pencil methods because the large number of categories of some tables for responses made computer-assisted methods unwieldy. For example, some tables of responses were so large that the type-size needed to display them on one screen would be too small to see. Eligibility criteria included: (1) having injected illicit drugs in the past 12 months, (2) age 18 or older, (3) residency in the NYC metropolitan area, and (4) fluency in English. After the interviewers described the study procedures and interview topics, and explained the risks and benefits, participants provided written informed consent. Participants were paid $30 for their time and effort. Study methods and questionnaire items were approved by NDRI’s Institutional Review Board. Interviews usually took approximately one and a half to 2 h. Participants generally reported that they enjoyed the interview topics and felt respected.

In addition to the investigational measures, the questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics, and HIV risk behavioral variables to help in testing criterion validity. For example we asked about participating in exchange sex (sex exchanged directly for money, drugs or other goods) in the last 30 days. We also added items regarding events surrounding Hurricane Sandy, which hit NYC in late 2012 just before we began enrolling participants for the quantitative sample.

Analysis

Our new pathways measures consist of items, scales, and indexes. We use the term “index” to refer to summed responses to theoretically related interview questions that are in the form of binary categories (e.g., the number of formal groups participants were involved with). Responding affirmatively to one index item may or may not be related to responding affirmatively to any other items in the same index. We use the term “scales” to refer to summed responses to theoretically related and correlated responses that are in an ordinal Likert-type form. Likert scale items had corresponding text to serve as behavioral anchors (e.g., “none of the time,” “all of the time”).

Reliability

We assessed scale reliability with Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency analysis. Items in unidimensional scales are assumed to be positively inter-correlated, reflecting associations with the underlying construct that the scale attempts to measure. We designed each scale to measure a single unidimensional construct. We removed items with item-total correlations below 0.20 on the assumption that such items were not strongly related to the construct. Cronbach’s alpha values at or above 0.70 are often considered reliable for basic research purposes, although in applied settings values above 0.80 are preferred [41]. Alpha values tend to increase with the number of items as long as the items are positively correlated. For instance, for a 5-item scale to achieve an alpha of 0.80, the average inter-item correlation would need to be 0.50; whereas, for a 10-item scale the average inter-item correlation would need to be only 0.29 [42]. We report scales as an unweighted average of constituent items in order to avoid omitting cases due to a single missing response. Some responses were reverse-coded so that items in the same scale reflected the same direction towards or away from the underlying construct. Online Appendix A describes the pathways measures more completely, including the range and item-total correlations for scale items, and describes the excluded items.

In addition to the potential new pathways measures we included a questionnaire section on social situation vignettes, with specific responses designed to reflect the characteristics represented in the pathways measures. For example, we asked:

If an older friend or relative suggests that people should only have sex after marriage and then only with their wife or husband what is your reaction likely to be?

Then we asked whether participants endorsed one of several possible responses that corresponded with specific pathways concepts, or sometimes more than one pathways concept. For example, one response: “I see this as showing that she or he is old-fashioned and out of date” may reflect Intergenerational Normative Disjuncture (C8 and C9, Table 2) or Traditional Cultural Orientation (C13, in Table 2). Although vignettes item responses have not themselves been validated as indicators of HIV infection risk, the different question framing and format provides information regarding how consistently the underlying construct is associated, an assessment of alternate form reliability [43]. We use three of the vignettes response-based items in place of criterion validators, where none otherwise existed.

Validity

Validity refers to the degree to which a measure reflects the thing it is purported to measure. To help explore elements of the validity of the new pathways measures we compared their associations with criterion variables. Specific criterion variables for each pathway measure were sometimes clear. For example, we used self-reported consistent condom use during multi-partnered sex events as a criterion variable for norms regarding sexual HIV-risk at multi-partnered sex events. For other variables, however, criterion variables were less obvious. For some measures we assessed divergent validity by comparing correlations with criterion variables that were expected to have differential associations according to theory. For example, Intergenerational Disjuncture scales for younger or older PWID were expected to have correlations in opposite directions with the number of recent sex partners and syringe sharing, based on theory. To facilitate comparisons of associations with criterion variables we used Pearson’s correlations. For other bivariate comparisons we used χ2 or t-tests for independent samples. Measurement error and differential skew attenuate associations with criterion variables [44]. However, for clarity we did not make any statistical adjustments of these associations.

CHAT Domain A: Norms, Rules and Roles in Proximal Social Contexts

We developed scales on friends’ and relatives’ norms, rules and roles regarding organizational participation, sexual behavior and drug use.

For Norms on Participating in Group Activities we asked what proportion of close relatives and what proportion of friends whom participants hang out with encouraged participants to take part in different kinds of organizational or group activities or political demonstrations. For example, we asked: “In the last year, what proportion of your close relatives actually encouraged you to take part in new or recently-growing formal or informal organizational or group activities?”

For Norms on Increasing Sexual Risk Behavior we asked what proportion of close relatives, friends, and other people participants hang out with encouraged participants to increase their sexual risk behavior. For example, we asked: “In the last year, what proportion of your friends or other people you hang out with have encouraged you to have sex with more people?”

For Norms on Injectable Drug Behaviors we asked what proportion of close relatives, friends, and other people participants hang out with encouraged the participant to use or to inject injectable drugs (opiates, cocaine or amphetamines). For example, we asked: “In the last year, what proportion of your friends or other people you hang out with have encouraged you to use heroin, crack, cocaine or speed?”

Previous research suggested that some drug users sometimes attended multi-partnered sex events, and that sex sometimes took place at venues where people gathered to use drugs [45, 46]. During the course of formative research, the importance of norms, rules and specific roles of some individuals at events or venues where more than two people had sex or injected drugs became evident. For Rules at Multi-partnered Sex Events we asked at what proportion of these events were there rules regarding different aspects of HIV avoidance and physical safety. For example, we asked, “How often were there rules (written or unwritten) that said: You need to change condoms every time you change partners.” For Sex Norms Enforcement at Multi-partnered Sex Events we asked at what proportion of multi-partnered sex events there were specific roles for certain individuals to enforce behavioral norms. For example, we asked, “How often was there somebody who enforced the condom use rules?” For Sex Rules at Drug-using Venues we asked participants who reported attending venues where they and two or more other people gathered to use drugs to recall whether there were norms, rules or specific roles for individuals regarding who could attend and regarding sexual HIV-risk avoidance. For example, we asked, “How often were there rules (written or unwritten) that said: You can’t get too drunk or high?” For Drug Use Norms, Rules and Roles at Drug-Using Venues we asked how often there were norms, rules or specific roles for individuals regarding injection-related HIV-risk avoidance at drug-using venues. For example, we asked, “At what proportion of these occasions did people actually object if someone tried to share syringes?”

For Injection Norms in the Context of Opiate Withdrawal we asked about the extent of agreement with norms regarding avoiding HIV transmission while injecting drugs, specifying whether the drug injector is experiencing drug withdrawal or not. For example, we asked: “When I am in withdrawal or about to be in withdrawal, people I inject with would object to my using a syringe that someone with HIV had just used.”

In the aftermath of big events, the extent to which people need to depend on others for different resources can change. We asked about Dependency on Relatives, Friends or Service Agencies for various needs, including a place to live, food and emotional support. Dependency scales could be coded as indexes, in that the categories of needs met by relatives, friends or service agencies could simply be summed, but we used ordinal response categories under the assumption that the self-rated frequency of dependence among these categories could add important information.

CHAT Domain B: Activities

We developed and measured two investigational categories of activities—involvement with formal and informal social groups; and frequency of helping others.

Details about Involvement with formal and informal social groups have been published elsewhere [24]; however, briefly, we asked participants if they were involved with two lists of potential social groups that we characterized as “formal” (33 categories) or “informal” (13 categories). For some topics, such as playing sports, there could be both formal and informal groups. Formal group topics included religious/church, sports, school, and labor unions. Informal group topics included sports, tenants, hanging out, and video gaming.

In addition, we asked participants about their experiences helping others, and doing things for relatives, other people they knew, and for the community where they lived. We asked how much time they spent helping others, and the frequency of helping with specific issues, such as economic or emotional problems. For example, we asked “How often, in the last 12 months, have you helped your close relatives seek assistance for their alcohol or drug problems?”

CHAT Domain C: Perceived Micro-social Conflicts and Reactions

One aspect of social change is that it may increase or decrease normative conflicts such as dignity denial, in which a person is insulted, demeaned or otherwise made to feel that they are not worthy of respect [47–52]. We developed scales for dignity denial frequency and how participants and others reacted to it. We developed a dignity denial perpetrators index by asking: “Please tell me who are the people and/or groups who have attacked your dignity or demeaned you in the way that hurt you the most.” We included 39 categories of people/groups, such as mother, father, neighbors, co-workers, strangers and police officers. We developed a Dignity Denial Characteristic Targeting index by asking about which of 25 characteristics participants perceived were the target of these dignity denial incidents, such as participants’ race, drug use, poverty or living situation. For Dignity Denial Reaction we asked participants the frequency of different kinds of reactions to having their own dignity attacked, such as crying, responding physically or verbally, or increasing their drug or alcohol use. For example, one response category was: “I shrug it off, pretend I don’t care, and do nothing.” For Witnessing Dignity Denial Perpetrators we asked participants the frequency of witnessing the denial of the dignity of 39 categories of others, such as their mother, father, friends or strangers, and who the people who denied others’ dignity were. For witnessing dignity denial reaction we asked participants about the frequency of different kinds of reactions they themselves engaged in when they witnessed others having their dignity attacked, such as consoling the person. For example, we asked: “When this occurs in your presence, what proportion of the time do you tell the person or people who are attacking the person’s dignity to stop it?”

Some of the relatives, friends, or people who hang out with people who use drugs sometimes make nasty comments to or about people who use drugs or engage in various sex practices. Others physically attack such people. And others offer them assistance. For witnessing verbal and physical attacks on others; and for witnessing defense of, and assistance to others, we asked participants what proportions of friends or the people they hang out with, and what proportion of close relatives, made nasty comments about or to other people; threatened or physically attacked other people; openly defended other people, and offered concrete assistance to other people for using drugs, trading sex for money, going to sex parties or for being gay or having gay sex.

One potential pathway between big events and HIV epidemics is intergenerational disjuncture, in which youth either become alienated or find that the degree to which their behavior is controlled by the norms of older generations is reduced; or conversely, in which older adults become alienated from youth [16, 53]. We developed scales for intergenerational disjuncture for younger (IGD-Y) and older (IGD-O) adults. Items for these scales tapped into aspects of disjuncture, for example: “The older generation’s ideas about prioritizing sacrifice over fun just don’t work for me and my generation.” We asked participants who were aged 18–24 to respond to questions regarding IGD-Y, and older participants to respond to questions regarding IGD-O.

Cultural Themes

We and others have discussed how the history of African Americans has led to the existence of cultural themes (sets of outlooks and norms) that help shape how people react towards various risks and opportunities, their own behaviors and the behaviors of others, and how they react to normative communication [54, 55]. Related themes—though perhaps with different content—seem to exist among other racial/ ethnic groups, in the lower and working classes of the U.S. and other countries; and perhaps also among MSM and among PWID and other drug users. Women have been held to have developed similar cultural themes [56]. We developed measures of altruistic, solidaristic, struggle, traditional, competitiveness, hostility, and survival cultural orientation as related to such themes.

Details about Altruistic and Solidaristic Cultural Orientation scales are presented elsewhere [57]. However, briefly, for Altruistic Cultural Orientation we asked participants the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with nine statements expressing altruism or the lack of altruism. For example, we asked: “In times like these, we should make sure no one goes hungry.” Questions on Solidaristic Cultural Orientation asked about agreement with nine statements regarding feelings of shared aims and commonality, such as: “Drug users like me need to support each other.”

A struggle-based theme in African American culture has grown out of long traditions of both micropolitical struggle and more overtly political movements against oppression, both within institutions and in the nation as a whole. Some African Americans who have actively responded to the HIV epidemic had experience in the civil rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s that led them to see HIV policies and programs as continuations of past struggles. For Struggle Cultural Orientation we asked about the extent of agreement with statements regarding social conflicts and struggle. For example, we asked: “In times like these, neighbors in my community need to fight against gentrification.”

The socially conservative and traditionally moralistic propriety theme reflects the widespread religious involvement of many African Americans (and others) and the tendency of oppressed groups to conform to the norms of the dominant social order [58, 59]. For Traditional Cultural Orientation we asked about the extent of agreement with statements regarding traditional attitudes towards drugs and sexual behavior; for example: “Seeking sex for pleasure is a sin.” For Competitiveness Cultural Orientation we asked about the extent of agreement with statements regarding competitive aggressiveness; for example: “I do whatever it takes to get ahead.” For Hostility Cultural Orientation we asked about the extent of agreement with statements regarding hostility or resentment; for example: “I dislike most of my neighbors.”

A survival theme is important in African American culture. A subset of the survival theme is the “code of the streets,” which centers around men’s need in some neighborhoods to have reputations as being willing to respond to provocation with violence [60]. This code emphasizes manhood as physicality and having sex with women. The code of the streets creates cultural environments conducive to high-risk sex, drug dealing and drug use. A more positive aspect of the survival theme is the rapid spread of messages of danger and of ways to avoid it through community grapevines. For Survival Cultural Orientation we asked about the extent of agreement with statements regarding difficult choices people make to survive; for example: “In times like these, it is ok to exchange sex for food or shelter.”

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics and risk behaviors are shown in Table 1. As is usual in studies of NYC PWID, participants were majority male, mainly in their 30 and 40 s, and had limited education.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, criterion validity items and selected vignettes items

| Characteristic | % (n)/mean (standard deviation)a,b |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 19–29 | 17.6 (52) |

| 30–39 | 28.5 (84) |

| 40–49 | 33.6 (99) |

| 50–62 | 20.3 (60) |

| Gender (% male) | 56.3 (169) |

| Racial category | |

| White | 43.7 (117) |

| Black/African American | 54.5 (146) |

| Otherc | 1.8 (4) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 42.7 (128) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 43.7 (131) |

| Married or living together | 31.3 (94) |

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 25.0 (75) |

| Educational achievement | |

| Less than high school graduation | 37.7 (112) |

| High school graduate or GED | 43.7 (131) |

| More than high school graduate | 18.7 (56) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed full-time or part-time | 20.0 (60) |

| Student | 3.3 (10) |

| Unable to work due to disability or retired | 16.6 (50) |

| Homemaker | 4.7 (14) |

| Unemployed | 53.3 (160) |

| Other, including illegal activities | 2.0 (6) |

| Income category (per year) | |

| Less than $10,000 | 62.1 (185) |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 35.9 (107) |

| $20,000 or more | 2.0 (6) |

| Number of dependents (mean (SD)) | 1.8 (1.13) |

| Veteran of U.S. armed forces or reserves | 19.1 (51) |

| Homeless status | 19.4 (56) |

| HIV infection status (% positive) | 20.8 (60) |

| Brought others assistance subsequent to Hurricane Sandy | 59.0 (177) |

| Sexual behavior | |

| Number of sex partners (last year) (mean (SD)) | 2.3 (2.75) |

| Exchanged sex for money, drugs or other goods (last 30 days) | 14.0 (42) |

| Attended multi-partnered sex events (last year) | 17.1 (50) |

| Used condoms consistently during multi-partnered sex events (last year) | 47.7 (21) |

| Injection drug use behavior | |

| Shared syringes (last 30 days) | 27.9 (83) |

| Shared drug preparation equipment (last 30 days) | 35.6 (106) |

| Vignettes items | |

| Vignette If an older friend or relative suggests that people can get good jobs if they study hard at school, what is your reaction likely to be? | |

| 1. The only way to get a good job is to cheat nowadays (mean (SD)) | 3.0 (1.56) |

|

Vignette “Things are really hard in this city right now. Jobs are hard to get and easy to lose. Benefits keep getting reduced. Social services keep getting cut back. In times like these | |

| 2. You have to look out for yourself even if someone else gets hurt (mean (SD)) | 4.0 (1.32) |

| 3. If you have a job, you need to do whatever it takes to keep it (mean (SD)) | 4.9 (0.36) |

N = 300 people who inject drugs

Percentage and (n), unless otherwise noted mean and (standard deviation)

Sample sizes (n) for category percentages vary due to non-response for some items, and percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding

Other = American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific islander, and multiple racial groups

Table 2 lists pathways measures in the three CHAT domains, their numbers of items, Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability values for scales, and Pearson correlations with the conceptually most clearly related criterion variables. Scale reliabilities were consistently high, with the exception of Norms on Participating in Sexual Behavior (0.62) and Sex Norms Enforcement at Multi-partnered Sex Events (0.64), where they were marginally acceptable. Results of analyses of data regarding multi-partnered sex events reflect responses from 48 participants who reported attending them in the last year. Results of analyses of data regarding drug-using venues reflect responses from 239 participants who reported attending them in the last year.

Correlations with validators were generally high, but depended on how direct the scale or index construct was related to the validator. For example, Involvement with Formal Social Groups and Involvement with Informal Social Groups were only modestly related with sharing drug preparation equipment (r = −0.21, 0.18, respectively), but were opposite in direction. This is consistent with our recent findings regarding the apparent protective effects of formal social groups against injection risk behavior [61]. Many validity correlations were strong and in the expected direction. For example, Norms on Increasing Sexual Risk Behaviors was strongly correlated with the number of recent sex partners (r = 0.71), and Dependency on Relatives and Dependency on Friends were negatively correlated with income (r = −0.23, =−0.34, respectively). Other correlations were smaller. For example, the Frequency of Helping Others scale was only modestly correlated with actually assisting others during Hurricane Sandy (r = 0.13). Several Dignity Denial scales were correlated with current homelessness.

Intercorrelations among the new pathways measures are presented in Online Appendix B. Most intercorrelations were minimal, and most of those greater than the absolute value of 0.2 were in the expected direction. Thus, most new measures show considerable independence from each other.

Discussion

Results of this study represent the initial steps of a complex multi-step process of developing measures of potential pathways in order to enable research on big events/structural interventions. Analyses of data from future research using some of the 30 new scales and indexes produced through this study may provide insights for better understanding potential pathways that could not previously be examined. Below, we summarize findings and implications of the measures, grouped by domain.

CHAT Domain A: Norms and Roles in Proximal Social Contexts

The eight new pathways scales regarding norms and roles in proximal social contexts show evidence of good reliability and validity. These measures reflect norms, rules and social roles in specific contexts that may be more relevant for HIV prevention than more general norms, such as those regarding syringe sharing overall. Norms regarding HIV risk behaviors, including those regarding participating in multi-partnered sex events, can change greatly following big events. For example, enforcement of HIV risk reduction rules at sex events or drug-using venues may break down if there is less physical security and risk behaviors need to be completed in less time.

Injection norms in the context of withdrawal is a clear potential target of social-behavioral or structural intervention. As is suggested by previous research, it might be useful to train PWID to use non-injection means of opiate ingestion in the context of experiencing withdrawal without access to sterile syringes [62–64]. Alternately, increased access to syringes, including during potential emergencies, can lead to maintained safe injecting [26].

CHAT Domain B: Activities

The tendency to join or participate in groups and to engage in helping behaviors may be affected by big events and could be targeted by structural interventions. For example, promotion of pro-social or HIV risk-reduction groups can impact risk behavioral norms, and subsequent risk of transmission [24]. Big events can lead to changes in group affiliations to cope with the new conditions. For example, in Eastern Ukraine, following recent conflicts with Russia, individuals have been pressured to join local militias [65, 66]. Research with other samples could help confirm whether participating with some formal social groups offers protective benefits against HIV risk behaviors, or whether less risky individuals self-select into formal social groups.

Helping behaviors contradict stereotypes of drug users as totally self-centered and destructive. We found ample evidence of PWID willing to help others, and actually helping others during the Hurricane Sandy emergency [26]. This should be unsurprising, but counters the stereotype of drug users as utterly self-interested and antisocial.

CHAT Domain C: Perceived Micro-social Conflicts and Reactions

We developed 16 scales and 3 indexes regarding perceptions of micro-social conflicts and reactions to them that show evidence of good reliability and validity, or-at minimum-significant associations with HIV risks or other relevant characteristics. The likelihood of normative conflicts is greatly increased following big events [18]. New pathways scales and indexes we developed can be used to assess early and later impacts of big events, which may vary as norms change diffuses across subpopulations. For example, intergenerational disjuncture can indicate generational differences in attitudes towards the risks associated with particular drugs [67]. Such intergenerational differences are presumed to have led to the end of the epidemic of crack use in the U.S. [68].

Altruism and solidarity may decrease, and pressure to compete and the frequency of dignity denial may increase in the face of big events [57]. Experiences of dignity denial and stigma may lead to later increases in HIV risk behavior [69]. The importance of processes of dignity-denial and of struggles over human dignity and stigma to how people respond to social change became evident in interviews with participants, who responded to economic conditions and perceived behavioral norms in ways that affirmed their own dignity [47].

Some patterns of intercorrelations among the new measures are notable. For example, Altruistic Cultural Orientation correlates strongly positively with Struggle and Solidaristic Cultural Orientations (r = 0.8, 0.8), and negatively with Traditional Cultural Orientation (r = −0.5). New measures should have divergent validity—they should measure something different than what is already measured, and they should not be highly correlated among themselves [41]. The potential for overlap among the measures limits their independent value. There may not be enough variance among Altruistic, Struggle and Solidaristic Cultural Orientations to justify their use as independent scales among PWID in New York. They may represent a single underlying construct, or represent such similar constructs that differential associations are unlikely to be observed. On the other hand, less overlap may be observed in different times or places with different structural intervention or big events histories, or among different populations, such as MSM or young adults. Other measures, such as Involvement with Formal Social Groups, Intergenerational Normative Disjuncture for older adults and Witnessing Dignity Denial Reaction had few inter-correlations above the absolute value of 0.2. High correlations of Norms on Increasing Sexual Risk Behaviors with several CHAT category C scales and with Intergenerational Disjuncture may be due to the influence of participating in sex exchange. Norms on Increasing Sexual Risk Behaviors was correlated with recently engaging in sex exchange (r = 0.6).

Limitations

There are several important limitations to the interpretation of our results. While participants were referred to us from a large study using respondent-driven sampling, we can make no claims regarding the representativeness of the results. Some of the items were deleted because of no or low variance. These items may exhibit variance in data collected from other samples. There was some evidence of agreement bias. Competitiveness Cultural Orientation results may have been influenced by this problem. We have changed the order of some questions, added validity scale items, and reversed the direction of some responses for future data collection. Some questions, such as those regarding norms, were challenging to understand for some participants. Researchers using the measures developed in this study should be careful to limit the interview burden, considering the complexity and the number of questions for the language skills of participants, in order to maximize accuracy. Results regarding IGD-Y, Rules at Multi-partnered Sex Events, and Sex Norms Enforcement at Multi-partnered Sex Events should be interpreted with caution because only 18 participants were aged 18–24 and provided IGD-Y responses, and only 48 participants reported attending multi-partnered sex events and provided responses about them.

Our limited number of criterion variables and our setting in a location with unclear relation to previous big events limits our ability to fully examine the utility of the new measures. We did not test reliability over time, and some of the variables we used for tests of criterion validity had little empirical basis. Since we were attempting to develop measures for constructs or processes that were not previously measured the lack of well-defined criterion variables for some new measures was expected. We do not know how NYC’s recent history may have affected our results. While the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy of 2011 impacted PWID and others in New York in the short-term [26, 70], it is unclear to what extent these events affected the pathways measures or the HIV epidemic. The consequences of the fiscal crisis of the 1970’s may have laid the groundwork for the HIV epidemic that began shortly thereafter, but the distance in time makes quantitative analysis of this question challenging [71].

Future Research

This study represents our initial attempt to develop new measures of potential pathways by which structural interventions or big events can affect HIV epidemics. The ultimate usefulness of the measures will be determined through this future research. It is important to note that the scales and indexes can be used selectively. For example, a study of the effects of stigma and dignity denial on HIV risk behaviors may incorporate our Dignity Denial indexes and Dignity Denial Reaction scales into their study, without including any of our other measures.

Further validation of the new pathways measures will be accomplished by comparing differences among groups as predicted by theory. For example, we may expect participants who belong to multiple stigmatized groups, such as PWID who are also MSM, to have more experiences of dignity denial than participants who belong to only one stigmatized group. More conclusive analyses of validity could be realized if the new measures were assessed in different settings, particularly before and after a big event or structural intervention.

Conclusions

Many of the pathways measures produced through this study seem useful for HIV research. Their utility and efficiency should be tested over time and in varying contexts of structural interventions and/or big events. Understanding these pathways may help us to improve structural interventions, and interventions designed to prevent HIV outbreaks and epidemics following big events. We encourage the unrestricted use of these measures by other investigators (see Online Appendix A).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grants R01DA031597 and P30DA011041. The International AIDS Society (IAS) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the post-doc fellowship of GN. We also acknowledge support from the University of Buenos Aires Grants UBACyT 20020130100790BA and UBACyT 20020100101021.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/sl0461-016-1291-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Parkhurst JO. Structural approaches for prevention of sexually transmitted HIV in general populations: definitions and an operational approach. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19052. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdul-Quader AS, Collins C. Identification of structural interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention: the concept mapping exercise. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(6):777–788. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:143–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson-Gomez J, et al. Resources and obstacles to developing and implementing a structural intervention to prevent HIV in San Salvador, El Salvador. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buffardi AL, et al. Moving upstream: ecosocial and psychosocial correlates of sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1128–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SR, et al. Social intervention against AIDS among injecting drug users. Br J Addict. 1992;87(3):393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine Committee on the Social Behavioral Science Base for HIV/AIDS Prevention Intervention, Assessing the Social and Behavioral Science Base for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Intervention: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, Ward TP. Social models for changing health-relevant behavior. In: Peterson RDRJ, editor. Preventing AIDS: theories & methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blankenship KM, et al. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Friedman SR. HIV among drug users at Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City, the first 25 years. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(2–3):131–139. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pouget ER, et al. Receptive syringe sharing among injection drug users in Harlem and the Bronx during the New York State expanded syringe access demonstration program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):471–477. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000152395.82885.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jolley E, et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: a systematic review with implications for policy. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001465. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCree DH, et al. African Americans and HIV/AIDS: understanding and addressing the epidemic. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi D. This special issue of substance use & misuse explores ”big events,” substance use its interventions. Introduction. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):823–824. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1024957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman S, Rossi D, Flom PL. “Big events” and networks. Connect (Tor) 2006;27(1):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman SR, Rossi D, Braine N. Theorizing “big events” as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolopoulos GK, et al. Big events in Greece and HIV infection among people who inject drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50:1–14. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman SR, et al. Theory, measurement and hard times: some issues for HIV/AIDS research. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):1915–1925. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0475-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paraskevis D, et al. HIV-1 outbreak among injecting drug users in Greece, 2011: a preliminary report. Eur Surveill. 2011;16(36):19962. doi: 10.2807/ese.16.36.19962-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strathdee SA, et al. Complex emergencies, HIV, and substance use: no “big easy” solution. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1637–1651. doi: 10.1080/10826080600848116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vygotsky L. In: Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. John-Steiner V, Cole M, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonteiev A. Activity, conciousness and personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi D, et al. Changes in time-use and drug use by young adults in poor neighbourhoods of Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina, after the political transitions of 2001–2002: results of a survey. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Jones Y, Mateu-Gelabert P. Formal and informal organizational activities of people who inject drugs in New York City: description and correlates. J Addict Dis. 2015;34(1):55–62. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.975612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolopoulos G, et al. Normative pressure for safe injecting: a comparison between New York City and Athens, Greece; 20th International AIDS Conference; Melbourne, Australia. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouget ER, et al. Immediate impact of hurricane sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Substance Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878–884. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff-Michael R, Lee Y-J. Vygotsky’s neglected legacy. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77:186–232. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards A. Working collaboratively to build resilience: a CHAT approach. Soc Policy Soc. 2007;6:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cianelli R, et al. Predictors of HIV enacted stigma among Chilean women. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(17–18):2392–2401. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao S, et al. The role of enacted stigma in parental HIV disclosure among HIV-infected parents in China. AIDS Care. 2015;27(Suppl 1):28–35. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1034648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman SR, et al. Drug scene roles and HIV risk. Addiction. 1998;93(9):1403–1416. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.939140311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biradavolu MR, et al. Structural stigma, sex work and HIV: contradictions and lessons learnt from a community-led structural intervention in southern India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii95–ii99. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeffries WLT, et al. Unhealthy environments, unhealthy consequences: experienced homonegativity and HIV infection risk among young men who have sex with men. Glob Public Health. 2015;7:1–14. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1062120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latkin CA, et al. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blankenship KM, et al. Structural interventions for HIV prevention among women who use drugs: a global perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S140–S145. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latkin C, et al. Relationships between social norms, social network characteristics, and HIV risk behaviors in Thailand and the United States. Health Psychol. 2009;28(3):323–329. doi: 10.1037/a0014707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latkin C, et al. The dynamic relationship between social norms and behaviors: the results of an HIV prevention network intervention for injection drug users. Addiction. 2013;108(5):934–943. doi: 10.1111/add.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Latkin CA. The phenomenological, social network, social norms, and economic context of substance use and HIV prevention and treatment: a poverty of meanings. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(8/9):1165–1168. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawlowicz MP, et al. Drug use and peer norms among youth in a high-risk drug use neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. Drugs. 2010;17(5):544–559. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner KD, et al. The perceived consequences of safer injection: an exploration of qualitative findings and gender differences. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(5):560–573. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.498890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. McGraw-Hill series in psychology. 3rd. xxiv. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. Psychometric theory; p. 752. [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeVellis RF. Applied social research methods series. 3rd. ix. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2012. Scale development: theory and applications; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen MJ, Yen WM. Introduction to measurement theory. x. Monterey: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co; 1979. p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furr RM, Bacharach VR. Psychometrics: an introduction. 2nd. xxiii. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014. p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedman SR, et al. Group sex events and HIV/STI risk in an urban network. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):440–446. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181893f31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman SR, Mateu-Gelabert P, Sandoval M. Group sex events amongst non-gay drug users: an understudied risk environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(11):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman S, Rossi D, Ralόn G. Dignity denial and social conflicts. Rethinking Marxism. 2015;27(1):65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobson N. Dignity and health: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson N. Dignity violation in health care. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(11):1536–1547. doi: 10.1177/1049732309349809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobson N. Dignity and health. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobson N, Oliver V, Koch A. An urban geography of dignity. Health Place. 2009;15(3):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simic M, Rhodes T. Violence, dignity and HIV vulnerability: street sex work in Serbia. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mills TC, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):278–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lightfoot MA, Milburn NG. HIV prevention and African American youth: examination of individual-level behaviour is not the only answer. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11(7):731–742. doi: 10.1080/13691050903078824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk Among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tait V. Poor workers’ unions: rebuilding labor from below. 1st. xi. Cambridge: South end Press; 2005. p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedman SR, et al. Measuring altruistic & solidaristic orientations towards others among people who inject drugs. J Addict Dis. 2015;34(2–3):248–254. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2015.1059654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Myers HF. African-American sexuality and HIV/AIDS: recommendations for future research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(1):44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31173-1. 50–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller RL., Jr African American churches at the crossroads of AIDS. Focus. 2001;16(10):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson E. Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. 1st. New York: W.W Norton; 1999. p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Friedman SR, et al. Formal and informal organizational activities of people who inject drugs in New York City: description and correlates. J Addict Dis. 2015;34(1):55–62. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.975612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mateu-Gelabert P, et al. The staying safe intervention: training people who inject drugs in strategies to avoid injection-related HCV and HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(2):144–157. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vazan P, et al. Correlates of staying safe behaviors among long-term injection drug users: psychometric evaluation of the staying safe questionnaire. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1472–1481. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris M, Treloar C, Maher L. Staying safe from hepatitis C: engaging with multiple priorities. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(1):31–42. doi: 10.1177/1049732311420579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roth A. A seperatist militia in Ukraine with Russian fighters holds a key. New York: New York Times; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Powell A. Ukraine volunteer militia deploys to east during cease-fire. Voice of America. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnston LD. Toward a theory of drug epidemics. In: Donohew HESL, Bukoski WJ, editors. Persuasive communication and drug abuse prevention. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Subcultural evolution and illicit drug use. Addict Res Theory. 2005;13(3):217–229. doi: 10.1080/16066350500053497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saewyc E, et al. Enacted stigma and HIV risk behaviours among sexual minority indigenous youth in Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. Pimatisiwin. 2013;11(3):411–420. doi: 10.111/jpc.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiss L, et al. A vulnerable population in a time of crisis: drug users and the attacks on the World Trade Center. J Urban Health. 2002;79(3):392–403. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freudenberg N, et al. The impact of New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis on the tuberculosis, HIV, and homicide syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):424–434. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.