Abstract

AIM: To report the results of fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy.

METHODS: A retrospective review was conducted at a single facility. Cases were identified using a computerized database and all clinic notes and operative reports were reviewed. All patients with epilepsy and recurrent shoulder instability were included for study. Between July 2003 and August 2011 five shoulders in five consecutive patients with epilepsy underwent fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. The mean duration of epilepsy in the cohort was 21 years (range, 5-51) and all patients suffered from grand mal seizures.

RESULTS: Mean age at the time of surgery was 47 years (range, 32-64). The cohort consisted of four males and one female. Mean follow-up was 4.7 years (range, 4.3-5 years). There were no further episodes of instability, and no further stabilisation or revision procedures were performed. The mean Oxford shoulder instability score improved from 8 preoperatively (range, 5-15) to 30 postoperatively (range, 16-37) (P = 0.015) and the mean subjective shoulder value improved from 20 (range, 0-50) preoperatively to 60 (range, 50-70) postoperatively (P = 0.016). Mean active forward elevation improved from 71° preoperatively (range, 45°-130°) to 100° postoperatively (range, 80°-90°) and mean active external rotation improved from 15° preoperatively (range, 0°-30°) to 40° (20°-70°) postoperatively. No cases of scapular notching or loosening were noted.

CONCLUSION: Fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty should be considered for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Dislocation, Epilepsy, Instability, Shoulder

Core tip: Epileptic patients with recurrent shoulder instability pose a significant challenge. We have reported the first series in the literature of patients with epilepsy-related recurrent shoulder instability to be treated with fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse anatomy arthroplasty. Our results suggest that it is successful in reducing pain and eliminating actual and perceived instability in this population. Contrary to previous reports there were no cases of glenoid loosening, implant failure or revision procedures. Postoperatively, there was a significant improvement in functional outcome, which was accompanied by a mean improvement of 25° in active external rotation and 29° in active forward flexion.

INTRODUCTION

Epileptic seizures can cause shoulder dislocation and instability[1]. The incidence of dislocation during a seizure is approximately 0.6% but this is likely to be an underestimation since many may be undetected because medical management of the seizure often takes precedence[2,3]. Recurrent instability is common and occurs soon after the first dislocation, with anterior and posterior instability occurring equally[1]. Significant bone loss from the glenoid rim and fossa, and corresponding extensive humeral head fractures are held responsible for this and are recognized as being a hallmark of the condition[1,4,5]. To address this, the majority of non-arthroplasty (“conservative”) surgical strategies focus on restoration and/or augmentation of the bony glenohumeral joint while also addressing capsular insufficiency and arthritis[6,7]. Despite technically satisfactory reconstruction (“preservative”) procedures some patients still experience persistent instability and increasing arthritis symptoms. Further conservative reconstruction becomes an unenviable prospect due to poor bone stock, large joint surface defects, and rotator cuff musculotendinous and capsular insufficiency. The patients are often young, in education or seeking work, and find the prospect of living with a painful unstable shoulder unbearable. In this context, arthrodesis has been reported to be a successful treatment strategy but the limitation in range of movement that inevitably results means that it is not suitable for all patients[8]. Constrained arthroplasty may therefore represent an alternative treatment option.

The Bayley-Walker shoulder (Stanmore Implants Worldwide Ltd, United Kindom) was specifically conceived for the treatment of patients with difficult shoulder reconstruction problems such as advanced rotator cuff arthropathy and tumours[9,10]. The device is a constrained fixed-fulcrum reverse anatomy prosthesis comprising a large-pitched, hydroxy-apatite-coated titanium glenoid screw with a 22 mm CoCrMo alloy head that forms a constrained “snap-fit” articulation (to increase stability) with an UHMWPE liner encased in a tapered titanium alloy humeral component giving 60° of intrinsic motion in any direction[10]. The center of rotation is placed medially and distally to the axis of the normal shoulder, which increases the lever arm of the deltoid, but to a lesser degree than most existing non-linked reverse anatomy prostheses[9]. These features make the Bayley-Walker prosthesis a potential treatment option for recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy who have sufficient glenoid bone stock for secure primary fixation of the glenoid component. There are no reports of this management strategy in the current published literature.

The aim of this retrospective study was to report the results of fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty (FF-RSA) for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between July 2003 and August 2011 five shoulders in five consecutive patients with epilepsy underwent FF-RSA for recurrent instability. Cases were identified using a computerized database and all clinic notes and operative reports were reviewed. The mean duration of epilepsy in the cohort was 21 years (range, 5-51) and all patients suffered from grand mal seizures. The index dislocation occurred a mean of 15 years (range, 2-38) before FF-RSA surgery. All cases were performed by the senior authors (J I L Bayley, Deborah Higgs, and Simon M Lambert). Mean age at the time of surgery was 47 years (range, 32-64) and the cohort consisted of four males and one female. All patients had anterior instability. Three patients had bilateral symptoms. The dominant shoulder was affected in three cases. FF-RSA was performed after an average of two previous stabilisation procedures (range, 0-5) in all but two patients in whom the procedure was used as primary treatment (Cases 3 and 5). All patients had had an onset of instability that coincided with a seizure. In all cases subsequent dislocations occurred during normal activities or further seizures.

The indication for surgery was severe pain and recurrent or persistent (i.e., the shoulder was never able to be actively centralised) instability with a non-functioning rotator cuff. The glenoid bone stock was judged on computer tomography (CT) to be sufficient for primary implantation of the glenoid screw component. Neurological advice was sought preoperatively in all cases to optimise the treatment of the epilepsy. Detailed patient data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient details

| Case | Gender | Age | Previous stabilisation procedures | Duration of follow-up (yr) | Additional procedures |

| 1 | Male | 41 | Putti-Platt procedure; Allograft humeral head reconstruction; Coracoid transfer; Revision allograft humeral head reconstruction | 4.3 | - |

| 2 | Female | 64 | Coracoid transfer | 4.6 | - |

| 3 | Male | 48 | No previous stabilisation procedures | 4.8 | - |

| 4 | Male | 32 | Putti-Platt procedure; Bankart repair; Revision Bankart repair; Allograft humeral head reconstruction; Humeral head resurfacing | 5.0 | Examination under anaesthesia and arthrocentesis due to persistent pain |

| 5 | Male | 51 | No previous stabilisation procedures | - | - |

Surgical technique

The deltopectoral approach was used in all patients. The glenoid was exposed and a Bayley-Walker uncemented glenoid screw was inserted using standard instrumentation. The humeral canal was prepared, and a Bayley-Walker humeral stem was inserted. A simple sling was used for 6 wk postoperatively during which period passive rotation at waist level was permitted; active scapular postural and motion exercises were encouraged. An active anterior deltoid activation programme was initiated after the first phase when osseo-integration of the glenoid screw was considered likely to have been achieved.

Assessment of radiological and functional outcome

Preoperative and postoperative radiographic imaging was performed in all cases and included anteroposterior and axillary views. Scapular notching was classified by the size of the defect on the anteroposterior radiograph using the four-part grading system devised by Sirveaux et al[11]. Humeral loosening was assessed from anteroposterior radiographs as described by Boileau et al[12].

Preoperative and postoperative clinical outcome measures included active forward elevation, active external rotation, and the Oxford Shoulder Instability score (OSIS)[13]. Range of movement was assessed by the operating surgeon and/or an orthopaedic resident. The OSIS is a 12-item questionnaire that places a significant emphasis on the impact the patient’s shoulder instability has on their lives, making it a highly discriminant tool to assess the efficacy of interventions used to treat it. In addition, all patients were assessed using the subjective shoulder value (SSV). The SSV can be used as a supplementary tool to traditional, more complex outcome measures and may be used in conjunction with other scores to assess the patients’ outcome. It has also been suggested to be a more sensitive measure of shoulder function in patients with instability[14].

Statistical analysis

The paired t test was used to compare OSIS and SSV before and after surgery. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. The SPSS software package, version 22 (SPSS Inc, an IBM Company, Chicago, Illinois) was used to analyse data.

RESULTS

Mean follow-up was 4.7 years (range, 4.3-5 years). One patient was deceased (Case 5) and was therefore exempt from functional outcome analysis. There were no further episodes of instability or persistence of apprehension, and no further stabilisation procedures and no revision procedures were performed. All patients were on medical treatment for their epilepsy and had been reviewed by a neurologist preoperatively. No cases of scapular notching or loosening of either the humeral or glenoid component were noted.

Mean active forward elevation improved from 71° preoperatively (range, 45°-130°) to 100° postoperatively (range, 80°-90°) (P = 0.418). Mean active external rotation improved from 15° preoperatively (range, 0°-30°) to 40° (20°-70°) postoperatively (P = 0.221). Clinical outcome following constrained fixed-fulcrum reverse shoulder arthroplasty can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical outcome following constrained fixed-fulcrum reverse shoulder arthroplasty

| Case | Active forward elevation in degrees (preop/postop) | Active external rotation in degrees (preop/postop) | Oxford shoulder instability score (preop/postop) | Subjective shoulder value (preop/postop) |

| 1 | 130/80 | 30/25 | 5/32 | 0/60 |

| 2 | 45/80 | 20/20 | 15/37 | 50/70 |

| 3 | 60/90 | 10/70 | 6/33 | 20/60 |

| 4 | 50/150 | 0/45 | 7/16 | 10/50 |

Preop: Pre operation; Postop: Post operation.

The mean OSIS improved from 8 preoperatively (range, 5-15) to 30 postoperatively (range, 16-37) (P = 0.015). The mean SSV improved from 20 (range, 0-50) preoperatively to 60 (range, 50-70) postoperatively (P = 0.016). Following surgery all patients reported less pain and avoided fewer activities due to the fear of a further dislocation. An improvement in dressing and washing was also noted in all cases. The results from the OSIS are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Change in the Oxford Shoulder Instability score following constrained fixed-fulcrum reverse shoulder arthroplasty

| Item | No. of patients reporting an improvement | No. of patients reporting worsening | No. of patients reporting no change |

| No. of dislocations | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Dressing oneself | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Worst pain | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Interference with work | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Avoidance of activities due to fear of dislocation | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Prevented activities of importance | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Interference with social life | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Interference with sport/hobbies | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Frequency with which patient thinks about their shoulder | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Willingness to life heavy objects | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Base-line level of pain in shoulder | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Avoidance of certain positions when sleeping | 2 | 0 | 2 |

One patient (Case 4) complained of persistent pain and underwent arthrocentesis to exclude an infective cause. No organisms were isolated and the patient reported an excellent outcome at the latest follow-up characterized by an improvement in functional outcome.

Case presentations

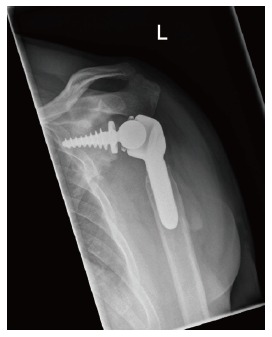

Case 1: A 41-year-old male with epilepsy was evaluated for a painful and unstable glenohumeral joint eight years after the index dislocation. Four previous stabilisation procedures had been performed, but due to persistent symptoms FF-RSA was undertaken. Following surgery, there was a reduction in pain and an improvement in range of movement due to a stable glenohumeral joint. No prosthetic complications were noted at the latest follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior radiograph of a 41-year-old right hand-dominant male with 4 previous stabilizations, 4 years after a right Bayley-Walker fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Case 2: A 64-year-old female epileptic with a 38-year history of glenohumeral instability was reviewed for an unstable shoulder and severe pain. Preoperative CT demonstrated advanced osteoarthritis with subchondral cysts, subchondral sclerosis, and narrowed joint space. FF-RSA was carried out successfully with no implant-related complications. At the latest follow-up, instability had been eliminated and there was a concomitant reduction in pain, and an improvement in function.

Case 3: A 48-year-old male with epilepsy was assessed for a painfully unstable glenohumeral joint two years after the first dislocation. No previous stabilisation procedures had been performed. FF-RSA was undertaken in the setting of an inactive rotator cuff and functioning deltoid. Postoperatively, there were no episodes of instability and the patient was satisfied with the outcome (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior radiograph of a 48-year-old left hand-dominant male, one year after a left Bayley-Walker fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Case 4: A 32-year-old epileptic male was reviewed following an 11-year history of glenohumeral instability. Five previous surgeries had been undertaken, including a humeral head resurfacing arthroplasty for dislocation arthropathy. FF-RSA was considered due to ongoing symptoms. At the time of surgery, the humeral head resurfacing implant was loose and there were arthritic changes on the glenoid. One year following surgery the patient complained of persistent pain and so arthrocentesis was undertaken. This did not demonstrate any infective cause and the pain eventually settled (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Anteroposterior radiograph of a 32-year-old right hand-dominant male with 5 previous stabilizations, 3 years after a left Bayley-Walker fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Case 5: A 51-year-old epileptic male was evaluated following a 16-year history of recurrent glenohumeral instability. No previous stabilisation procedures had been undertaken. At the time of surgery, a full-thickness rotator cuff tear was noted. No implant-related complications were detected following surgery. However, the patient later died of an unrelated medical condition.

DISCUSSION

Shoulder instability can be a significant problem in patients with epilepsy. Management is challenging as seizures exert considerable forces on surgical repairs. It is therefore imperative that a neurologist is involved preoperatively so that medical treatment can be optimized. Patients with epilepsy are prone to recurrence and often undergo multiple operations to achieve a stable shoulder joint[1]. With each successive procedure the risk of complications increases and the chance of a successful outcome is reduced. Only a small proportion of cases remain refractory to conventional surgery but these patients often have distorted anatomy and multiple soft tissue defects that make further reconstruction challenging and fraught with complications. To address this, Thangarajah et al[8] reported the outcome of six epileptic patients with recurrent instability followed-up for a mean of 39 mo who were treated with glenohumeral arthrodesis. Mean age of the cohort was 31 years. An overall improvement in functional outcome was noted, predominantly due to the reduction in pain and elimination of instability, but due to the restriction in range of movement and limitation in function it could not be recommended ubiquitously. In this context, constrained shoulder arthroplasty could be a potential alternative but there are no studies examining this strategy in an epileptic population.

Constrained shoulder arthroplasty is characterised by mechanical coupling of the humeral and glenoid components around a fixed center of rotation (hence the terminology “fixed-fulcrum” total shoulder arthroplasty). FF-RSA was initially considered as a potential solution for rotator cuff arthropathy but early designs were associated with loosening and implant failure, with relatively poor ranges of motion compared with the emerging anatomical designs[15,16].

The Bayley-Walker shoulder replacement is a constrained FF-RSA device that has been used for complex reconstruction problems in which the rotator cuff is absent (proximal humeral tumour excision), severely deficient (rotator cuff arthropathy), or likely to be compromised with the passage of time (post-traumatic arthropathy, particularly when associated with disruption of the coraco-acromial arch)[9,10]. Its design includes a conical shaped glenoid screw that reduces the strain placed on the implant, and “snap-fit” components that enhance stability and place the center of rotation medially and distally to the axis of the normal shoulder in order to increase the lever arm of the abductors[9,17].

Post et al[18] reported the results of 43 constrained total shoulder replacements performed in 42 patients. Follow-up was for a minimum of 27 mo. Indications for surgery included osteonecrosis, complex fractures, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and failed arthroplasty. Twelve material failures were noted in 22 stainless steel implants but only two were found in 21 cobalt-chromium prostheses. Glenoid loosening was not encountered. Traumatic dislocation occurred in four cases. Revision surgery was undertaken in 13 patients and was due to further traumatic episodes causing dislocation and material failure. Maintenance of the glenoid vault was found to be essential for secure fixation of the glenoid component and so the authors discouraged the use of constrained arthroplasty in conditions that caused excessive bone loss such as tumours and severe osteoporosis. Coughlin et al[19] evaluated the results of 16 semi-constrained total shoulder arthroplasties performed for intractable pain and severe degenerative disease. Follow-up was for a mean of 31 mo, with one failure due to mechanical loosening. An improvement was noted in total range of motion. Griffiths et al[10] reviewed a series of 68 consecutive patients who underwent replacement of the proximal humerus for tumour using a massive endoprosthesis. The mean age of the group was 46 years and follow-up was for a mean of 5 years 11 mo. An unconstrained endoprosthesis was implanted into the first 64 patients and a custom-made constrained (Bayley-Walker) reverse polarity fixed-fulcrum implant linked to a massive proximal humeral endoprosthesis was used in the remaining four. No dislocations were noted in the group with a constrained implant at a mean of 14.5 mo following surgery. This was in contrast to the unconstrained group who had a dislocation rate of 25.9%. No cases of glenoid loosening were identified in the cohort.

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) has been established as an effective treatment for rotator cuff arthropathy in an older patient population with low functional demands[20]. Few studies have examined its use in patients under the age of 60 years with those that do reporting serious complications in the short-term such as the need for revision and dislocation[21,22]. Muh et al[21] retrospectively reviewed 66 patients with a mean age of 52 years who underwent RTSA. Prior surgical procedures were common with 67% of the cohort having at least one prior intervention. At a mean follow-up of 36.5 mo there was an improvement in range of movement and functional outcome. Ten complications were identified including five dislocations that required revision in three cases and three infections that required further surgery. Scapular notching was found in 43% of patients. Sershon et al[22] evaluated 35 patients with a mean age of 54 years that underwent RTSA for a range of indications such as rheumatoid arthritis, failed rotator cuff repair, instability sequelae and cuff tear arthropathy. Of these, 83% had previous surgery averaging 2.5 procedures per patient. At a mean follow-up of 2.8 years there was an improvement in range of movement and functional outcome. Six patients had major complications including three dislocations, one subluxation and two fractures. Furthermore, three patients had revision surgery at 2 mo, 6 mo and 2.8 years.

Younger patients requiring shoulder arthroplasty present several challenges as they have higher functional demands and require longer implant survival when compared to elderly patients. In our series, FF-RSA was used in patients with a mean age of 47 years. At short-term follow up there was an improvement in functional outcome with no dislocations or revisions. This suggests that FF-RSA may be able to overcome some of the problems associated with more traditional reverse anatomy designs and provide a suitable alternative to invasive fusion surgery in a younger population. However, further long-term studies are required because clinical outcomes have been noted to deteriorate with time following RTSA[23].

We have reported the first series in the literature of patients with epilepsy-related recurrent shoulder instability to be treated with fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse anatomy arthroplasty. Our results suggest that it is successful in reducing pain and eliminating actual and perceived instability in this population. Contrary to previous reports there were no cases of glenoid loosening, implant failure or revision procedures. Postoperatively, there was a significant improvement in functional outcome as illustrated by an increase in the OSIS and SSV. This was accompanied by a mean improvement of 25° in active external rotation and 29° in active forward flexion. This is in contrast to other studies in which limitation of active external rotation characterises reversed-polarity semi-constrained prostheses[24-26]. We attribute our findings to the maintenance of teres minor and recruitment of the posterior deltoid, which can work more effectively against a fixed fulcrum with its less-medialised center of rotation[27].

Limitations of this small cohort study include those associated with its retrospective design and the mean follow-up of 4.7 years, which is relatively short in terms of prosthesis survivorship. However, Uri et al[27] have shown that if a FF-RSA is becoming loose, it is usually apparent within this time frame. We believe that these prostheses can obtain durable fixation through secondary osseointegration even in the challenging environment of a patient in whom epilepsy is a concomitant problem. This study of a unique group of patients previously considered poor candidates for shoulder arthroplasty provides some evidence of the value of FF-RSA in the treatment of a difficult and relatively uncommon problem. Further prospective studies examining the performance of this implant in this and similarly challenging patient populations in which the stability of conventional reverse-polarity arthroplasty remains uncertain are warranted.

In conclusion, epileptic patients with recurrent shoulder instability pose a significant challenge. Traditional operative measures may be unsuccessful and multiple revisions are common. In our series, FF-RSA eliminated recurrent instability and significantly improved functional outcome. This was accompanied by an improvement in pain and range of movement (external rotation and forward flexion). When managing this complex patient group, medical optimisation is essential and we therefore recommend that a neurologist be involved at the earliest possible juncture.

COMMENTS

Background

Epileptic patients with recurrent shoulder instability pose a significant challenge. Significant bone loss from the glenoid and humeral head is a common finding. Patients are often young, in education or seeking work, and find the prospect of living with a painful unstable shoulder unbearable. In this context, arthrodesis has been reported to be a successful treatment strategy but the limitation in range of movement that inevitably results means that it is not suitable for all patients. The purpose of this study was to report the results of fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy.

Research frontiers

The authors have reported the first series in the literature of patients with epilepsy-related recurrent shoulder instability to be treated with fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse anatomy arthroplasty. This study of a unique group of patients previously considered poor candidates for shoulder arthroplasty provides some evidence of the value of fixed-fulcrum constrained reverse anatomy arthroplasty in the treatment of a difficult and relatively uncommon problem.

Innovations and breakthroughs

At a mean of 4.7 years follow-up, there were no further episodes of instability, and no further stabilisation or revision procedures were performed in the cohort. A significant improvement was noted in functional outcome, as assessed by the Oxford Shoulder Instability Score (P = 0.015) and Subjective Shoulder Value (P = 0.016). This was accompanied by a mean improvement of 25° in active external rotation and 29° in active forward flexion. No cases of scapular notching or loosening were noted.

Applications

Fixed-fulcrum fully constrained reverse shoulder arthroplasty should be considered for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy.

Peer-review

This is a well written paper regarding a very difficult clinical problem to manage.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This retrospective study was undertaken using data from medical records only and thus was conducted without IRB approval.

Informed consent statement: Our retrospective study contained data from medical records.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from any commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 14, 2016

First decision: February 29, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

P- Reviewer: Anand A, Fanter N, Garg B, Yamakado K S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Bühler M, Gerber C. Shoulder instability related to epileptic seizures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:339–344. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeToledo JC, Lowe MR. Seizures, lateral decubitus, aspiration, and shoulder dislocation: Time to change the guidelines? Neurology. 2001;56:290–291. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz TJ, Jacobs B, Patterson RL. Unrecognized dislocations of the shoulder. J Trauma. 1969;9:1009–1023. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provencher MT, Bhatia S, Ghodadra NS, Grumet RC, Bach BR, Dewing CB, LeClere L, Romeo AA. Recurrent shoulder instability: current concepts for evaluation and management of glenoid bone loss. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92 Suppl 2:133–151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thangarajah T, Lambert S. The management of recurrent shoulder instability in patients with epilepsy: a 15-year experience. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1723–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutchinson JW, Neumann L, Wallace WA. Bone buttress operation for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation in epilepsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:928–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raiss P, Lin A, Mizuno N, Melis B, Walch G. Results of the Latarjet procedure for recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder in patients with epilepsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1260–1264. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B9.29401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thangarajah T, Alexander S, Bayley I, Lambert SM. Glenohumeral arthrodesis for the treatment of recurrent shoulder instability in epileptic patients. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1525–1529. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.33754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahir SP, Walker PS, Squire-Taylor CJ, Blunn GW, Bayley JI. Analysis of glenoid fixation for a reversed anatomy fixed-fulcrum shoulder replacement. J Biomech. 2004;37:1699–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths D, Gikas PD, Jowett C, Bayliss L, Aston W, Skinner J, Cannon S, Blunn G, Briggs TW, Pollock R. Proximal humeral replacement using a fixed-fulcrum endoprosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:399–403. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B3.24421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boileau P, Gonzalez JF, Chuinard C, Bicknell R, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty after failed rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The assessment of shoulder instability. The development and validation of a questionnaire. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:420–426. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b3.9044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbart MK, Gerber C. Comparison of the subjective shoulder value and the Constant score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam D, Kepler CK, Neviaser AS, Jones KJ, Wright TM, Craig EV, Warren RF. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: current concepts, results, and component wear analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92 Suppl 2:23–35. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Post M, Jablon M. Constrained total shoulder arthroplasty. Long-term follow-up observations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(173):109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mordecai SC, Lambert SM, Meswania JM, Blunn GW, Bayley IL, Taylor SJ. An experimental glenoid rim strain analysis for an improved reverse anatomy shoulder implant fixation. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:998–1003. doi: 10.1002/jor.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Post M, Haskell SS, Jablon M. Total shoulder replacement with a constrained prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coughlin MJ, Morris JM, West WF. The semiconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1742–1747. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muh SJ, Streit JJ, Wanner JP, Lenarz CJ, Shishani Y, Rowland DY, Riley C, Nowinski RJ, Edwards TB, Gobezie R. Early follow-up of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients sixty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1877–1883. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sershon RA, Van Thiel GS, Lin EC, McGill KC, Cole BJ, Verma NN, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Clinical outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged younger than 60 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Favard L, Levigne C, Nerot C, Gerber C, De Wilde L, Mole D. Reverse prostheses in arthropathies with cuff tear: are survivorship and function maintained over time? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2469–2475. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1833-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1476–1486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1476–1485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulahia A, Edwards TB, Walch G, Baratta RV. Early results of a reverse design prosthesis in the treatment of arthritis of the shoulder in elderly patients with a large rotator cuff tear. Orthopedics. 2002;25:129–133. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20020201-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uri O, Beckles V, Higgs D, Falworth M, Middleton C, Lambert S. Increased-offset reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of failed post-traumatic humeral head replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]