Abstract

Objectives

To understand hospital‐ and county‐level factors for rural obstetric unit closures, using mixed methods.

Data Sources

Hospital discharge data from Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project's Statewide Inpatient Databases, American Hospital Association Annual Survey, and Area Resource File for 2010, as well as 2013–2014 telephone interviews of all 306 rural hospitals in nine states with at least 10 births in 2010. Via interview, we ascertained obstetric unit status, reasons for closures, and postclosure community capacity for prenatal care.

Study Design

Multivariate logistic regression and qualitative analysis were used to identify factors associated with unit closures between 2010 and 2014.

Principal Findings

Exactly 7.2 percent of rural hospitals in the study closed their obstetric units. These units were smaller in size, more likely to be privately owned, and located in communities with lower family income, fewer obstetricians, and fewer family physicians. Prenatal care was still available in 17 of 19 communities, but local women would need to travel an average of 29 additional miles to access intrapartum care.

Conclusions

Rural obstetric unit closures are more common in smaller hospitals and communities with a limited obstetric workforce. Concerns about continuity of rural maternity care arise for women with local prenatal care but distant intrapartum care.

Keywords: Rural hospitals, obstetric units, closures, birth volume, obstetric workforce

Over 28 million reproductive‐age women (18–44 years) live in rural areas of the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2012), but the number of rural hospitals providing obstetric care has decreased over the past two decades (Simpson 2011). This decrease raises concerns about access to maternity care and outcomes for the half million women who give birth each year in rural hospitals (Lorch et al. 2013; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2014).

Closure of hospital obstetric units or reduction of maternity services (e.g., providing only prenatal care, but not labor and delivery services) in rural areas may prolong travel time for rural women, who already travel further to access care than their urban counterparts (Rayburn, Richards, and Elwell 2012). Having to travel for obstetric care is associated with higher costs, greater risk of complications, and longer lengths of stay, along with financial, social, and psychological stress for patients (Sontheimer et al. 2008; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2014).

Hospital closures have been studied extensively (Holmes et al. 2006; Bazzoli et al. 2012), but few studies have specifically examined reasons for obstetric unit closures. A few studies have focused solely on obstetric unit closures in urban hospitals (Smits et al. 2009; Lorch et al. 2013). In one study of 27 rural hospitals that stopped providing obstetric services, the most frequently cited reasons for stopping were the low volume of deliveries in the hospital, difficulty staffing an obstetric unit, and financial vulnerability due to high proportions of patients on Medicaid (Zhao 2007).

In this paper, we used qualitative and quantitative methods to identify hospital and community factors that may precipitate closure of rural obstetric units.

Methods

Data and Study Population

We conducted a telephone survey of rural hospitals that provided obstetric services in nine states: Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin, from September 2013 to March 2014. The survey sample consisted of all 306 rural hospitals in these nine states with at least 10 births in the 2010 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project's (HCUP) Statewide Inpatient Databases (SID). The SID all‐payer databases include 100 percent of hospital discharges; obstetric deliveries were identified using a validated algorithm (Kuklina et al. 2008). The nine states were chosen because of their sizeable rural population, the number of rural hospitals providing obstetric care, their regional distribution, and the availability of hospital identifiers in the SID data, which allow linkage with other data sources, including the American Hospital Association Annual Survey (AHA) and the Area Resource File (ARF). Rural hospitals were identified based on the Office of Management and Budget nonmetropolitan county definition.

A multidisciplinary team, including an advisory panel of rural hospital obstetric unit managers, collaborated to design the survey instrument. A total of 263 hospitals responded to the survey, yielding an 86 percent response rate. The 43 nonresponding hospitals were similar to responding hospitals on most characteristics, but they were less likely to be critical access hospitals or publicly owned and had higher birth volume on average than responding hospitals that continued providing obstetric services or those that closed the units (Appendix SA2). The survey responses were subsequently merged with SID, AHA, and ARF data to create an analytic dataset. Nineteen of the 263 hospitals reported no longer doing deliveries; administrators at these hospitals were asked about the date of closing the obstetric unit, the reasons for closure, and the availability of prenatal care in the community after unit closures.

This analysis compares the 19 rural hospitals that closed their obstetric units during 2011–2014 with the 244 hospitals that continued providing obstetric services.

Dependent and Independent Variables

The primary outcome of analysis was obstetric unit closure. Explanatory variables of interest were selected based on the literature on obstetric service provision (Lawhorne and Zweig 1989; Nesbitt 2002; Zhao 2007) and open‐ended responses to our telephone survey. They included system affiliation, ownership, payer mix, nurse staffing, birth volume, distance to and birth volume in the closest hospital providing obstetrics, and county‐level provider supply and population characteristics. Availability of prenatal care services in the community was a secondary outcome for the qualitative analysis.

Hospital‐Level Characteristics

Hospital organizational characteristics (e.g., accreditation, system affiliation, and ownership) were obtained from the 2010 AHA Annual Survey. Due to the small number of for‐profit hospitals in the sample, hospitals were categorized as private (including nonprofit and for‐profit) or public. AHA data were also used to calculate the number of registered nurse full‐time equivalents (FTEs) per 1,000 adjusted inpatient days, as well as the distance (geodetic and driving distance in miles) between each sample hospital and their closest hospital with 10 or more births using the corresponding latitude and longitude, and the number of births in the closest hospital, to serve as market influences.

Based on the previous literature (Zhao 2007), we hypothesized that hospital‐level birth volume and payer mix would be associated with a unit's financial viability and ability to remain open. Birth volume and payer mix (the percentage of women who either had Medicaid as the primary payer or were uninsured at the time of the birth hospitalization) for the sample hospitals came from the SID.

County‐Level Characteristics

The supply of obstetric providers in a county may influence a rural hospital's ability to continue providing obstetric services. Using ARF data, we calculated the number of obstetrician–gynecologists (OBGYNs) and certified nurse midwives per 1,000 females aged 18–40 years, and the number of family physicians per 10,000 population in 2010. To further capture socioeconomic characteristics in a county where a hospital was located, we derived the 2006–2010 median family income from ARF data. A proxy measure for obstetric care demand was the number of females aged 18–40 years in 2010 in the county where a hospital was located.

Analysis

We employed qualitative analysis of survey responses to determine reasons for closures and postclosure community capacity for prenatal care. While the question regarding capacity for prenatal care following closure was open‐ended, responses were easily classified into affirmative or negative responses regarding continued availability of obstetric services. Responses were further classified based on whether continued availability of prenatal care was accessible through the same hospital or clinic system or through another health care delivery system in the same community. The question regarding reasons for obstetric unit closure was analyzed using iterative inductive coding to identify salient themes. An a priori listing of themes was developed based on extant literature (Zhao 2007), including staffing concerns, low birth volume, low reimbursement rates, and other financial concerns (such as administrative issues, liability costs, etc.). Responses were categorized into the theme that most closely fit the content of the response. Some responses were categorized under more than one theme. Categorization of responses by salient theme was originally implemented by one author (PH) and confirmed by two coauthors (KBK, MMC).

In the quantitative analysis, to further examine bivariate relationships between explanatory factors and closures, two‐group t‐tests and Fisher tests were used. We then used logistic regression to estimate the likelihood of obstetric unit closure across hospitals using birth volume in 2010 when they were providing obstetric care. The likelihood was measured by odds ratios (ORs) using a crude model for each variable, and an adjusted model (adjusted ORs, AORs) controlling for potential confounders previously mentioned. We calculated the predicted probability of unit closures based on this model and the mean values for covariates (Table 1), to illustrate the association between hospital birth volume and obstetric unit closures. We computed robust standard errors to account for correlation between hospitals within states. To detect the potential collinearity issues between the covariates, we employed variance inflator factors (VIF) and tolerance measures from the regression. The VIF for all covariates ranged from 1.08 to 1.58, with the corresponding tolerance level of 1.03 to 1.26.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Rural Hospitals That Did and Did Not Close Obstetric Units, 2010–2014 (N = 263)

| Providing Obstetrics (N = 244) | Closed Obstetric Unit (N = 19) | p‐value for Differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % or Mean (SD) | N | % or Mean (SD) | ||

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Critical access hospitals | 125 | 51.2% | 15 | 83.3% | .006 |

| Hospital accreditation | 152 | 62.3% | 6 | 33.3% | .012 |

| Hospital system affiliation | 122 | 50.0% | 6 | 33.3% | .079 |

| Hospital ownership | |||||

| Government, nonfederal | 76 | 31.1% | 6 | 31.6% | .200 |

| Not‐for‐profit | 159 | 65.2% | 13 | 68.4% | .202 |

| For‐profit | 9 | 3.7% | 0 | 0.0% | .522 |

| Number of births in 2010 (SID) | 244 | 328.4 (283.6) | 19 | 86.9 (101.1) | < .001 |

| FTE RNs per 1,000 inpatient days | 244 | 3.3 (1.8) | 19 | 3.0 (1.8) | .528 |

| Payer mix: percent of mothers giving birth with public insurance or no insurance in 2010 (SID) | 244 | 53.7 (17.7) | 19 | 57.7 (26.9) | .527 |

| Market characteristics | |||||

| Distance† from closest hospital with OB services‡ | |||||

| Straight‐line geodetic distance (miles) | 244 | 21.6 (10.7) | 19 | 19.6 (9.9) | .352 |

| Driving distance (miles) | 244 | 30.4 (18.3) | 19 | 28.5 (12.1) | .645 |

| Birth volume in closest hospital with OB services† | 244 | 447.3 (591.1) | 19 | 399.4 (354.7) | .597 |

| County‐level characteristics (ARF 2010) | |||||

| Number of OBGYNs per capita among 1,000 females 18–40 years old | 244 | 0.55 (0.53) | 19 | 0.30 (0.34) | .006 |

| Number of FPs doing patient care per 1,000 population | 244 | 0.39 (0.22) | 19 | 0.26 (0.17) | .005 |

| Number of CNMs per capita among 1,000 females 18–40 years old | 244 | 0.37 (0.42) | 19 | 0.44 (1.2) | .573 |

| Median family income, 2006–2010 | 244 | 54,928 (9,341) | 19 | 50,407 (7,294) | .018 |

| Females 18–40 years in 2010 | 244 | 7,039 (20,231) | 19 | 4,576 (3,893) | .120 |

†Geodetic distance and driving distance in miles between a hospital and geographically mapped closest hospital was calculated, using corresponding latitude and longitude derived from AHA annual survey by SAS URL access method and Google Maps.

‡Definition of obstetric services is a hospital with at least 10 births reported in AHA 2010 Annual Survey.

CNM, certified nurse midwife; FP, family physician.

The descriptive analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA); the driving distance was calculated using SAS URL access method to Google Maps with hospitals' longitudes and latitudes from the AHA annual survey (Zdeb 2010). The regression analyses were with Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Among the 263 rural hospitals that responded to our survey, 7.2 percent closed their obstetric units between 2010 and early 2014 (Table 1). Unadjusted comparisons revealed that rural hospitals that kept their units open differed significantly from those that closed their obstetric units on several characteristics. Discontinuation of obstetric services was more likely to occur in critical access hospitals than other rural hospitals (83 percent vs. 51 percent, p = .006), and less likely in accredited hospitals (33 percent vs. 62 percent, p = .012). On average, obstetric units that remained open had almost fourfold the birth volume of closed units in 2010 (328 vs. 87 births, p < .001). Among the closed units, birth volume ranged from 11 to 726 births in 2010, while the units remaining open had from 10 to 1,610 births.

The average supply of obstetricians in counties where units remained open was about twice as high as in counties where units closed (0.55 vs. 0.3 per 1,000 females 18–40 years old, p = .006). The counties where units closed also had 0.13 fewer family physicians doing patient care per 1,000 population (0.26 vs. 0.39, p = .005), and over $4,500 lower median family income over the past 5 years ($50,407 vs. $54,928, p = .018) than unaffected counties. Unit closures did not vary significantly by system affiliation, hospital ownership, distance from the nearest hospital providing obstetric services, or the proportion of women who reported Medicaid as a primary payer or were insured for their birth hospitalization in 2010.

Among the 19 hospitals that closed their obstetric units, the most commonly cited reason for closure was difficulty in staffing the unit (n = 15), including retention, recruitment, and liability issues surrounding obstetricians. Other frequently cited reasons for closure included low birth volume (n = 9), low reimbursement (n = 3), and other financial issues (n = 6), such as surgical and anesthesia coverage, the cost of operating the units, and budget cuts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported Reasons for Rural Hospitals No Longer Doing Deliveries (N = 19)

| Number (%) of Respondent Hospitals | |

|---|---|

| Reasons for closures† | |

| Staffing issues | 15 (79%) |

| Illustrative quotations: | |

| “One OB retired and one moved. We didn't have the providers any more to offer this service.” | |

| “Our facility stopped doing OB … mainly based off of the inability to maintain consistent surgical and anesthesia coverage.” | |

| “We had two doctors and then one stepped away and we had a hard time recruiting. We had trouble with coverage for anesthesia as well.” | |

| “We stopped doing deliveries because we only had one provider doing deliveries. We lost a provider (FP) who no longer wanted to do OB services and we've been unable to recruit new doctors.” | |

| “too few staff or providers in the community to operate an OB unit” | |

| Low birth volume | 9 (47%) |

| Illustrative quotations: | |

| “We had a small number of births.” | |

| “… the volumes dropping to the point where nurse competencies were becoming difficult to maintain” | |

| “It was based on low numbers and high malpractice insurance.” | |

| “we averaged 18 births a year. Lacking experience and had to do a lot of training…” | |

| Other financial issues | 6 (32%) |

| “We were purchased by another system and it was a financial decision to close the OB department.” | |

| “OB Dept closed … due to budget cuts and also because there were other OB providers fairly close by.” | |

| “It wasn't making any profit and we have an older population.” | |

| “We were in the middle of a financial turnaround and the new administration decided to stop for financial reasons.” | |

| Low reimbursement rates | 3 (16%) |

| “80% were Medicaid and 10% no pay.” | |

Bold indicates primary themes.

†Some hospitals reported more than one reason.

Most of the rural hospitals that closed their obstetric units stated that prenatal care was still available in the community through hospital‐owned or affiliated clinics or private practices. However, two hospitals reported that women in their communities no longer have local access to prenatal care due to the obstetric unit closure. Rural women in these two communities will need to travel 25.4 miles and 40.8 miles to the nearest hospitals where obstetric services are available. Rural women in the 17 communities where obstetric units were closed but prenatal care is available will need to travel an average of 29 miles with a range from 9 to 65 miles to the next available hospital for obstetric care.

The survey responses revealed the challenges that rural hospitals face in providing obstetric services, as well as some of the trade‐offs they made when deciding to close an obstetric unit. One hospital explained, “A nurse practitioner/nurse midwife is providing care but will be leaving soon. Then there will be no prenatal care available for the community.” Other hospitals are only able to offer prenatal care for low‐risk women, explaining, “It's only well‐mom prenatal care up to 36 weeks (no high risk)…We then hand them off to an OB doctor…or a midwife in another community.”

Table 3 presents the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (AORs) for predictors of obstetric unit closures. The adjusted model, controlling for hospital, market, and county characteristics, as well as state clustering, explained one‐third of the variation in obstetric unit closures. In the unadjusted analysis, potential predictors associated with obstetric unit closures include annual birth volume (OR [95 percent confidence interval] = 0.28 [0.1, 0.75]), county‐level supply of OBGYNs (0.33 [0.11, 0.95]), county‐level supply of family physicians (0.64 [0.42, 0.98]), and county‐level median family income (0.94 [0.86, 0.99]).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios of Obstetric Unit Closure by 2010 Characteristics of Sample Hospitals (N = 263)

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)† | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)‡ | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital characteristics | ||

| Annual birth volume in 2010 (per 100) | 0.28 (0.10, 0.75) ** | 0.10 (0.02, 0.43) *** |

| Square of birth volume in 2010 (per 100) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) ** | 1.13 (1.04, 1.23) *** |

| System affiliation | 0.46 (0.17, 1.26) | 0.51 (0.16, 1.68) |

| Hospital ownership (ref. government/public) | ||

| Private | 0.98 (0.36, 2.68) | 3.84 (1.37, 10.77) ** |

| Proportion of noncommercially insured§ | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) |

| FTE RN per 1,000 inpatient days | 0.92 (0.70, 1.21) | 1.06 (0.82, 1.35) |

| Market characteristics | ||

| Number of births (per 100) in closest hospital | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.09) |

| County‐level characteristics | ||

| Number of OBGYNs doing patient care per 1,000 females 18–40 years old | 0.33 (0.11, 0.95) ** | 0.54 (0.15, 1.35) |

| Number of FPs doing patient care per 10,000 people | 0.64 (0.42, 0.98) * | 0.62 (0.43, 0.90) * |

| Number of CNMs per 1,000 females 18–40 years old | 1.24 (0.36, 4.24) | 1.28 (0.64, 2.55) |

| Median family income in 2006–2010 | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) * | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99) * |

| Females 18–40 years in 2010 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 1.01 (1.002, 1.03) * |

†Each variable's unadjusted odds ratio was derived from an individual model.

‡Adjusted McFadden's R‐square, referring to the amount of variance in odds of closures predicted by this model, is 0.326.

§Percent of women giving births in a hospital who had either Medicaid as the primary payer or who were uninsured at the time of hospitalization.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Bold indicates significant results at p < .05.

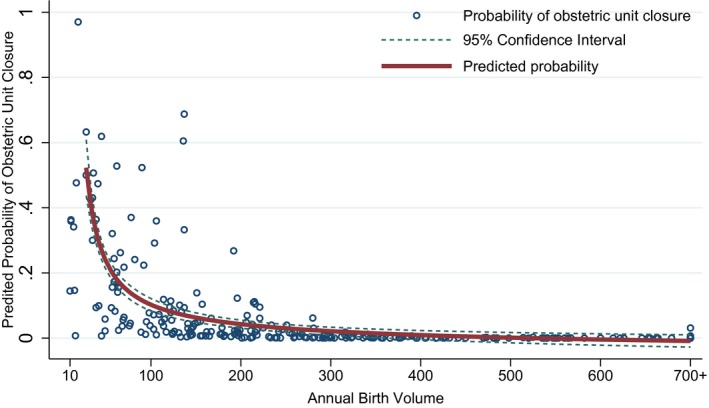

Holding other confounders constant, we found that private nonprofit and for‐profit rural hospitals had almost three times higher odds of closing their units (AORs = 3.84, 95 percent CI = [1.37, 10.77]; p = .008) than public nonfederal hospitals. Hospitals with 100 more births annually had 90 percent lower odds of obstetric unit closure (AORs = 0.10, 95 percent CI = [0.02, 0.43]; p < .001). Birth volume alone predicted about 10 percent of variation in the odds of unit closure. Figure 1 presents the predicted probability that a rural hospital would close its obstetric unit, by birth volume, based on mean values for covariates (Table 1) and the adjusted model (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Regression of Obstetric Unit Closures by Annual Birth Volume in 2010 (N=263)

Note. Predicted probabilities were calculated by multivariate logistic regression in Table 3, with average values of covariates, including hospital system affiliation, hospital ownership, proportion of noncommercially insured mothers, FTE Registered Nurses per 1,000 inpatient days, birth volume in the nearest hospitals doing obstetrics, and country‐level characteristics

The county‐level supply of family physicians, median family income over the past 5 years, and the population of reproductive‐age women were all negatively associated with unit closure. Rural hospitals in communities with an additional family physician per 10,000 population had 38 percent lower odds of obstetric unit closure (AOR = 0.62 [0.43, 0.90]; p = .014), and those in counties with a $1,000 higher median family income per year had almost 10 percent lower odds of unit closure (AOR = 0.92 [0.86, 0.99]; p = .047).

Discussion

Our analysis identified several significant risk factors associated with rural obstetric unit closures between 2010 and 2014. These factors include low birth volume, private hospital ownership, a limited local supply of family physicians, and location in a lower income county.

Although the predicted probability of obstetric unit closure increased significantly as birth volume decreased, high birth volume alone does not assure continued operation. One of the rural hospitals that stopped doing deliveries, for example, had 726 births in 2010, which is above the median birth volume for rural hospitals with obstetric units during that year. However, the significantly higher probability of unit closures among hospitals with lower than 100 annual births suggests that additional rural hospitals will be vulnerable to obstetric unit closure in the future.

Continued consolidation of obstetric services has potential implications both for the access and the quality of obstetric care in rural areas. Evidence on volume–outcome relationships in obstetrics is mixed (Phibbs et al. 2007; Kozhimannil et al. 2014a; Snowden and Cheng 2015). It is possible that closures of very low‐volume obstetric units may produce net benefits for women and infants in affected communities, if deliveries move to hospitals with sufficient birth volume to maintain provider skills, and adequate access to prenatal care is available. In the absence of appropriate regionalization of maternity care, rural women may end up utilizing local emergency departments for childbirth, given an average of 29 miles to reach the next nearest hospital with obstetric services. Further research is warranted to examine the effects of obstetric unit closures on local women's maternity care access, childbirth costs, and maternal/neonatal outcomes, including potential differential impacts on high‐risk and low‐risk pregnant women.

The significant association between the local supply of family and obstetric unit closures reflects the reliance of many smaller rural hospitals on family physicians to provide obstetric care (Zhao 2007; Tong et al. 2012). This finding is of particular concern given the challenges faced by rural communities in recruiting and retaining obstetric providers, as well as decreases nationally in the number of family physicians being trained to provide obstetric care and choosing to include obstetric care as part of their practices (Cohen and Coco 2009; Tong et al. 2013).

The lack of a significant relationship between payer mix and obstetric unit closure was somewhat surprising, given previous research indicating that a primary reason for closures was high rates of births to women who were covered by Medicaid or uninsured (Zhao 2007). Differences in payer mix across rural hospitals may be less important due to high rates of Medicaid coverage among rural pregnant women; over half of all rural women who gave birth in 2010 had their birth hospitalizations covered by Medicaid (Kozhimannil et al. 2014b). Obstetric unit closure was associated, however, with hospital location in a county with a lower median family income, suggesting that the overall financial status of the local population may influence a hospital's capacity to maintain obstetric services.

The greater likelihood of obstetric unit closures among private rural hospitals in our study, as compared to public hospitals, may be a function of public hospitals' focus on community needs. Previous research has found that obstetric services are “relatively unprofitable” and that rural public and nonprofit hospitals are significantly more likely to provide obstetric services than rural for‐profit hospitals (Horwitz and Nichols 2011).

A hospital's decision to discontinue obstetric services may depend on a wide range of factors, including leadership, political environments, the dynamics of the obstetric practice model, and patient–provider relationships (Zhao 2007; Haywood 2011). Change in hospital leadership was stated as one of the reasons for obstetric unit closures among our sample hospitals. However, our study was not able to measure hospital policies and obstetric care provider characteristics, such as specialty and years of practice, as factors that may have influenced the decision to close an obstetric unit.

Most rural hospitals in our survey reported that women continued to have access to prenatal care in their communities after closing their obstetric units. This finding is encouraging in terms of the potential for maintaining access to adequate prenatal care in these communities, but it underscores the importance of ensuring communication between local providers providing prenatal care and more distant delivery hospitals providing inpatient intrapartum care. Ongoing efforts should focus on encouraging linkages between maternity care providers and hospitals in perinatal systems of care, including using telemedicine and health information technology to help ensure continuity of maternity care.

Limitations

This study used data from nine geographically diverse states with large rural populations; however, the results may not be generalizable to other states. There are some limitations to measuring obstetric provider supply and demand factors at the county level, as care patterns may cross county lines. On average, 58.6 percent of the rural women in our analysis delivered in a hospital that was located in the same county as their county of residence. However, we included market characteristics based on travel distance in our analyses. Additionally, although obstetric units in hospitals with higher overall nurse staffing levels would likely have higher staffing levels, our hospital‐level nurse staffing variable may not reflect levels in obstetric units.

In summary, this mixed‐method study demonstrated that birth volume, private hospital ownership, and local characteristics such as lower median family income and limited family physician supply were associated with increased odds of obstetric unit closure in rural hospitals.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2. Characteristics of Rural Hospitals by Obstetric Unit Closure and Survey Responding Status (N = 306).

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was supported by the Rural Health Research Center Grant Program Cooperative Agreement from the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration (U1CRH03717‐09‐00). This work was also supported by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Grant (K12HD055887) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Health Resources and Services Administration. The authors are grateful for helpful input provided by Shailendra Prasad, MD, MPH; the rural hospital survey respondents; and the Office of Measurement Services at the University of Minnesota for fielding the survey. All authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to the financial or policy interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . 2014. “Health Disparities in Rural Women.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 123 (2 Pt 1): 384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoli, G. J. , Lee W., Hsieh H.‐M., and Mobley L. R.. 2012. “The Effects of Safety Net Hospital Closures and Conversions on Patient Travel Distance to Hospital Services.” Health Services Research 47 (1 Pt 1): 129–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D. , and Coco A.. 2009. “Declining Trends in the Provision of Prenatal Care Visits by Family Physicians.” Annals of Family Medicine 7 (2): 128–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, K. B. 2011. “Closing Maternity Wards: Costly and Risky.” Daily Yonder|Keep It Rural [accessed on May 17, 2014]. Available at http://www.dailyyonder.com/closed-maternity-wards-mean-more-health-risks/2011/04/18/3283

- Holmes, G. M. , Slifkin R. T., Randolph R. K., and Poley S.. 2006. “The Effect of Rural Hospital Closures on Community Economic Health.” Health Services Research 41 (2): 467–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, J. R. , and Nichols A.. 2011. “Rural Hospital Ownership: Medical Service Provision, Market Mix, and Spillover Effects.” Health Services Research 46 (5): 1452–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K. B. , Hung P., Prasad S., Casey M., McClellan M., and Moscovice I. S.. 2014a. “Birth Volume and the Quality of Obstetric Care in Rural Hospitals.” Journal of Rural Health 30 (4): 335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K. B. , Hung P., Prasad S., Casey M., and Moscovice I.. 2014b. “Rural‐Urban Differences in Obstetric Care, 2002‐2010, and Implications for the Future.” Medical Care 52 (1): 4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuklina, E. V. , Whiteman M. K., Hillis S. D., Jamieson D. J., Meikle S. F., Posner S. F., and Marchbanks P. A.. 2008. “An Enhanced Method for Identifying Obstetric Deliveries: Implications for Estimating Maternal Morbidity.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 12 (4): 469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhorne, L. , and Zweig S.. 1989. “Closure of Rural Hospital Obstetric Units in Missouri.” Journal of Rural Health 5 (4): 336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch, S. A. , Srinivas S. K., Ahlberg C., and Small D. S.. 2013. “The Impact of Obstetric Unit Closures on Maternal and Infant Pregnancy Outcomes.” Health Services Research 48 (2 Pt 1): 455–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, T. S. 2002. “Obstetrics in Family Medicine: Can It Survive?” Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 15 (1): 77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phibbs, C. S. , Baker L. C., Caughey A. B., Danielsen B., Schmitt S. K., and Phibbs R. H.. 2007. “Level and Volume of Neonatal Intensive Care and Mortality in Very‐Low‐Birth‐Weight Infants.” New England Journal of Medicine 356 (21): 2165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayburn, W. F. , Richards M. E., and Elwell E. C.. 2012. “Drive Times to Hospitals with Perinatal Care in the United States.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 119 (3): 611–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, K. R. 2011. “An Overview of Distribution of Births in United States Hospitals in 2008 with Implications for Small Volume Perinatal Units in Rural Hospitals.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 40 (4): 432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits, A. K. , King V. J., Rdesinski R. E., Dodson L. G., and Saultz J. W.. 2009. “Change in Oregon Maternity Care Workforce after Malpractice Premium Subsidy Implementation.” Health Services Research 44 (4): 1253–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, J. , and Cheng Y.. 2015. “The Impact of Hospital Obstetric Volume on Maternal Outcomes in Term, Non–Low‐Birthweight Pregnancies.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 212 (3): 308.e1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer, D. , Halverson L. W., Bell L., Ellis M., and Bunting P. W.. 2008. “Impact of Discontinued Obstetrical Services in Rural Missouri: 1990‐2002.” Journal of Rural Health 24 (1): 96–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S. T. C. , Makaroff L. A., Xierali I. M., Parhat P., Puffer J. C., Newton W. P., and Bazemore A. W.. 2012. “Proportion of Family Physicians Providing Maternity Care Continues to Decline.” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 25 (3): 270–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S. T. , Makaroff L. A., Xierali I. M., Puffer J. C., Newton W. P., and Bazemore A. W.. 2013. “Family Physicians in the Maternity Care Workforce: Factors Influencing Declining Trends.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 17 (9): 1576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . 2012. “2008‐2012 American Community Survey 5‐Year Estimates.” American FactFinder – Results B01001 [accessed on June 29, 2014]. Available at http://factfinder2.census.gov/

- Zdeb, M. 2010. Driving Distances and Times Using SAS and Google Maps. SAS Global Forum 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. 2007. Why Are Fewer Hospitals in the Delivery Business? Working paper #2007–04, Bethesda, MD: The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis – NORC Health Policy and Evaluation at the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2. Characteristics of Rural Hospitals by Obstetric Unit Closure and Survey Responding Status (N = 306).