Abstract

Introduction:

Birth can cause and post-traumatic stresses in many women even when the occasion of birth results in alive baby. Fetal death can challenge her understanding of justice and God's love toward his creatures. Religious beliefs have a considerable effect on decreasing individuals’ tendency toward bereavement; thus, it is expected to have a relationship with sorrow and mental distress ensuing fetal death. The present research has been conducted to review the existing literature on religion and fetal death and then study Iranian women and their families’ response to such a tragedy.

Materials and Methods:

This is a unsystematic (narrative) review. Research was conducted to study the role of mothers’ religious belief in their encounter with pregnancy loss in cases belonging to a 23-year period from 1990 to 2013. PubMed and Ovid databases and Iranian religious resources such as Tebyan were utilized for these studies. Of course, several articles were also derived by means of manual search.

Results:

Nine out of 31 papers had the searched keywords in common in the preliminary search. A review of the existing papers indicated that only 4 out of 22 papers dealt exactly with the role of religion on reaction of parents to fetal death. The four papers belonged to the years 2008, 2010, 2011, and 2012 indicating the new approach to religion in pregnancy loss cases.

Conclusion:

Religion has a significant effect on parents’ acceptance of such mishaps and it may have a considerable effect on their recovery from such tragic events.

Keywords: Fetal death, pregnancy loss, religion, stillbirth

INTRODUCTION

Stillbirth is a grave tragedy that shatters the emotional bond formed between the fetus and the parents.[1] In fact, the death of the fetus at any age and due to any reason proves an unsettling experience to a changing life.[2] Fetal death is an unexpected and sudden event that forces many changes in the life of affected parents. In response to stillbirth, parents would feel extremely sorrowful, traumatic, confused, hollow, and shocked as though one part of their being has died.[3]

Prenatal death is of specific characteristics that differentiates it from other types of death. These characteristics include closeness to the date of birth, parents being young when experiencing the loss, unexpectedness of the death, and the death being the first one experienced by the parents in their joint life.[4] In other words, stillbirth is one of the deepest and most significant losses that can be experienced by a woman, inflicting a broad range of cognitive, mental, spiritual, and physical turmoil. After stillbirth, most mothers look for answers to their questions on their baby's death. They may even reproach themselves in this quest.[5] Even three years after the stillbirth, the turmoil experienced by these mothers is approximately twice that of mothers with live babies.[6] Cacciatore, in a quote from Barr, indicated that there is a 30% probability that mournful mothers who have experienced stillbirth would commit suicide and a 13% probability that they would seek addictive drugs for adapting to the situation. Also 62% of such mothers stated, “I wish I could sleep and wake up to see all this had been a dream.”[7]

It is noteworthy that care-givers are in an exceptional situation in such conditions and must be able to facilitate the recovery process for such mothers from such sadness caused by the loss of their baby.[8] In other words, if these care-givers are not able to link the jovial nature of birth with the sadness of death, then the prenatal mournings will intensify.[4]

Roberts explained that culture, language, and religion played a crucial role in patients’ access and reaction to clinical services. He indicated that provision of medical care conforming to families’ culture, wherever they live, requires care-givers’ awareness and understanding of cultural and religious views toward life, birth, and death prevailing in that region.[9] Kresting also suggested that women's religious beliefs affects significantly their decision to stop or continue assisted reproductive techniques. In other words, religion is a cultural prescripion to finding the correct approach to issues such as death and religious ceremonies.[10]

In their encounter with stillbirth, different individuals hold different religious beliefs. Even atheists who doubt the certainty of death attempt to link this mishap to God's omnipotence. In this challenge, seeking the meaining of life, despite any individual religious orientation, can help mourning mothers pass through different stages of their grief and improve their sense of blamelessness.[7]

In other words, fetal death can trigger a spiritual crisis in women. Various considerations of this spiritual crisis are seeking the meaning of life, taking a distance from or getting closer to God, misunderstanding or consistency, or a conflict with regard to God.[11] Further to this mishap, mothers may review their religious beliefs and such a review may end in changes in their spiritual models as their quest for the meaning of loss conforming to their religious instructions proves conflicting. Death of a baby may challenge a mother's interpretation of justice and God's love toward his creatures. However, faith in God may light up hope in some individuals and soften such grave mishaps.[12]

Religious individuals tend to feel more satisfied with life and experience lower levels of depression and thus are less likely to commit suicide.[13] Patients with stronger beliefs, in comparison with those of wavering beliefs, pass medical crises more successfully.[14]

On the other hand, religious beliefs have a dramatic effect on an individual's response to grief and thus it is expected that there is a relationship with sorrow or other mental distresses caused by fetal death. In a systematic review study, it was specified that 94% of individuals confirmed the positive effect of religion and spiritual beliefs on their response to mourning.[15] Meryerstein studied the spiritual conditions inflicting the Jews and their religious resources used for maintaining their spiritual health in his paper entitled “A Jewish Spiritual Perspective on Psychopathology and Psychotherapy: A Clinician's View.” He also overviewed this subject in other religions. Meryerstein held that different people maintain a different approach toward this issue as their approach to solutions is different; for instance, some patients believe the solution is in God's hands and some believe that God helps the ones who help themselves. He concluded that spirituality could be an effective resource for treatment and that patients’ hope could be strengthened by forming a group of priests and clergymen or by referring the patients to religious groups.[16]

In all cases of sudden infant death in Islam, the oppurtunity of mourning and religious ceremonies is offered to the parents and they are ensured that infant's innocent spirit resides in heaven and in God's care.[17] The grief of miscarriage and stillbirth is not underestimated and is counted as a real death such that death certificates are issued for all dead fetuses. In other words, deceased fetuses are considered to have a real entity for parents. Islamic beliefs and traditions as those of Christianity and Judaism define a conceptual framework for encounter with loss and the ensuing grief. Cacciatore (2007a) also suggested that research works of the past 20 years have considered factors such as mother's age, her educational level, training and religion, and the number of children and their marital and occupational status as factors effective in mother's distress after her productive loss. In other words, although religion is not considered in many studies as a factor directly affecting pregnancy loss, religion is counted as an effective demographic factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review research was conducted to study the role of mothers’ religious belief in their encounter with pregnancy loss in cases belonging to a 23-year period from 1990 to 2013. Various databases such as PubMed, Ovid, and Tebyan as well as various papers, Iranian and religious resources were utilized for these studies. Researchers used the related papers by searching the term “stillbirth,” or “fetal death,” or “pregnancy loss” AND (“Judaism,” or “religion,” or “Christianity,” or “Islam”. 12 and 19 papers were selected from PubMed and Ovid databases, respectively. The objective of this review research was studying the role of religion in mothers’ encounter with pregnancy loss in research works conducted throughout the world and the current religious culture of Iran that is Islam.

Study selection

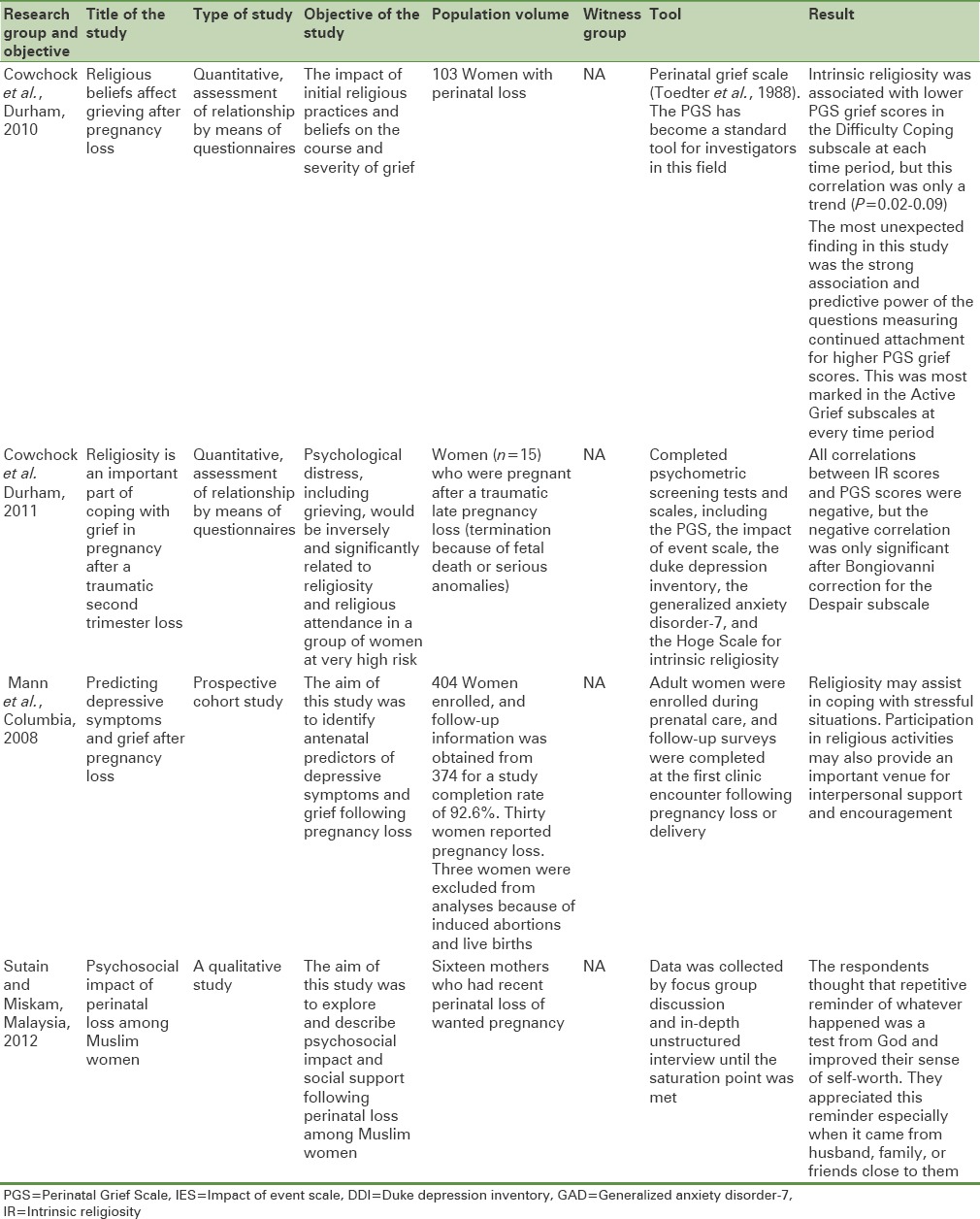

The inclusion criteria conditioned that papers should be in both Farsi and English and they must be accessible. The term still birth means the death of the fetus at any time from week 20 to the time of fetus’ birth. Thus, any papers on miscarriage or abortion were excluded from the scope of the current research work. Among the searched papers, those on the role played by religion in fetal death were selected. As a result, four research works were selected from yielded results in the world scale [Table 1].

Table 1.

Four of the 22 existing papers dealt precisely with the role of religion in fetus loss

RESULTS

Nine out of 31 papers, which were yielded in the initial search by the aforementioned keywords were common. Four of the 22 existing papers [Table 1] dealt precisely with the role of religion in fetus loss. The four papers belonged to the years 2008, 2010, 2011, and 2012, indicating the new approach to the issue of religion in mothers’ encounter with pregnancy loss, although traditional religious instructions have influenced people's life significantly. Faith in religion does not relate to any specific religion but refers to individual's participation in religious ceremonies and his/her self-reporting of specific religious practices. However, it is worth to note that most of subjects reviewed in the three papers were of Christian faith. A study of these papers and analysis of their content pointed out to three themes of grief as perceived by mothers, coping with mental distresses and acceptance of prenatal loss. These themes constitute the process through which an issue is perceived, coped with, and ultimately accepted.

Religion and grief as perceived by mothers

Cowchock et al. conducted a study entitled, “The effect of religious beliefs on grief after pregnancy loss” on 103 women and followed them up for one year to assess the effect of their beliefs and their basic religious practices on the duration and severity of grief. They concluded that the effect of religious beliefs is very complicated and instinctive such that a higher score of beliefs are related indirectly with an individual's maturity level and decreased stress, and are directly related with an individual's life events. In other words, an individual's religious beliefs are related to lower level of grief in each stage, even though the level of this relationship is very low. On the other hand, a significant direct relationship between constant attachment and level of grief was concluded.

According to Benore and Park, constant attachment and belief in relationship with the deceased are related. This is actually rooted in a belief in life after death.[18] In other words, the hypothesis of these researchers suggesting that instinctive religious beliefs are related with a lower score of mental sorrow after mother's loss was not confirmed. Furthermore, an individual's religious crisis may trigger a higher level of grief such that these women may suffer from chronic pathologic grief even one or two years after the event and should be referred to spiritual and mental care centers for treatment.[19]

Kresting et al.[10] reported that faith and strong religious beliefs along with social support could predict a lower level of grief inflicted by prenatal death as perceived by mothers. In other words, religious societies are support centers with rich social support resources such that parents’ participation in these societies and religious practices can help them accept these social supports more openly and experience a lower level of grief.[20]

Effect of religion on coping with mental distresses

Cowchock et al.[21] studied the score of internal religious beliefs and its relationship with psychometric tests and concluded that, although no relationship was identified between religious beliefs and psychometric tests in low-risk women who had experienced the loss in the first half of their pregnancy loss, the positive effect of religion was significantly confirmed in high-risk women's psychometric test such that the stronger an individual's beliefs, the lower the score of hopelessness and the grief experienced in that individual. They further stated that their study suggested that religious beliefs play an important role in mothers’ coping with the distressful conditions of pregnancies resulting in stillbirth.[19] Roberts et al., in their article entitled “Cultural and social factors related to prenatal grief,” pointed out that women in developed countries are identified and recognized by their child-bearing power and thus stillbirth may result in their exclusion from society at a time they greatly need social supports. They also pointed out that 80% of Indians are Hindus who exclude women from their religious ceremonies held for dead-born babies. This heightens women's prenatal grief while instinctive religious beliefs protect them in their encounter with this event.[22]

Thearle et al.,[23] in their study on Australian parents experiencing prenatal death, suggested that depression level was low in subjects from both control and experimental groups who used to go to church at least once a week. It is worth to note that the effect of religion on coping with mental distresses of pregnancy period are confirmed such that Mann et al. found out that religious orientations predict lower levels of postnatal depression.[24]

Thearle et al. studied the relationship between religious services and mental health of parents who had experienced stillbirth or baby loss. This study, which was conducted in England, specified that mothers who used to follow the religious practices such as going to church regularly showed lower levels of depression in comparison with mothers who participated irregularly or not at all in these ceremonies. Of course, the results of the research did not determine whether prenatal death caused parents to be more religious than before. A decrease in participation in religious ceremonies brought about a higher level of grief for mothers. However, an increase in participation in these ceremonies did not vary the level of grief. This indicates that constancy of participation is more connected with distress and grief level than the number of participations. In other words, it was concluded by the study that parents who participated in religious ceremonies constantly (both before and after fetus loss) coped better with the event than those who participated in religious ceremonies aimlessly and irregularly. Thearle et al. ultimately concluded that, considering the positive effect of religion on parents’ encounter with grief, the caregivers should facilitate parents’ participation in religious ceremonies if they believe they can connect their deceased baby with God by religious rites. This way this event would find a positive meaning. Caregivers are advised not to prevent such parents from participation in those cultural and religious ceremonies helping them cope with their grief.[23]

Religion and acceptance of prenatal loss

In a qualitative study conducted in Malaysia on the mental effects of prenatal death on Muslim women who formed centralized societies, it was specified that these women tried to find signs of life in themselves and have a positive outlook toward future. Four themes of parents’ impression of prenatal loss, acceptance of caregiver's role during the grieving period, supports during grieving period, and decision-making were classified. The support groups fell under religious practice category such that the women stated that their friends and family members encouraged them to be patient and perceive this event as a divine trial and ask God to help them cope with this issue. All these women stated that they could decrease their pain and cope better with this issue by religious practices. They also indicated that their babies had a great chance of life in the other world and they did not regret the condition [Table 1].[25]

Iranians also believe that their deceased babies have a great chance of life in the other world and they will be given back to their parents in the other world. “God entrusted Abraham and his wife with taking care of Muslims’ deceased babies in a magnificent palace; on the Resurrection Day, they will be clothed and scented properly and will be presented to their parents as gifts,” said Imam Sadeq (PBUH). These babies are kings in heaven with their parentsand this is what God meant by the statement “those who believe in God will get back their babies.”[17]

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Although the increased quality of midwifery care has decreased mortality rates of fetuses and babies, it is still considered as a tragic event that brings about many mental distresses for parents. Beliefs seem to have a significant positive effect on the grief perceived by parents and ultimately the decrease of mental distress and parents’ acceptance of the issue. Religious practices, regardless of their type, help parents cope better with this hurting event and facilitate their recovery. On the other hand, doctors and nurses’ attention to these beliefs can help with offering appropriate care to these parents.

The cultural and religious orientation of Iranians has caused them to seek religion for coping with such critical conditions. Islam recognizes deceased fetuses as real entities and ensures parents that their deceased babies will have a safe resting place. “When a baby passes away, angels cry out that so-and-so, the child of so-and-so, has passed away. If baby's either parents or one of his/her Muslim relatives have passed away, then the baby will be sent to them so they take care of the baby. And if neither parents or none of his/her relatives have passed away, then the baby will be sent to Fatima Zahra (PBUH) so she takes care of the baby till the time baby's either parents or any of his/her relatives pass away and join him or her,” said Imam Sadeq (PBUM).[17] According to a saying by Prophet Mohammad, my deceased fetuses are dearer to me than my live children.

This belief is rooted in Muslims’ different approach to life such that they view life as a complete cycle and not ending in death. It is believed in Islam that deceased fetuses will visit their parents at heaven gates. They even may guide their mothers if they are patient and have hope in God's rewards.[26] As a result, parents would act with more patience upon the death of their babies and cope better with the issue.

On the other hand, Islam instructs Muslims to seek God upon sorrowful and distressful situations. Religious anecdotes and instances, Prophet Mohammad's life story, their loss, and their approach toward such events will help them cope with sorrow and distress as mentioned in Muslim's Quran: “He guides to Himself those who turn to Him in penitence, those who believe and whose heart has rest in the remembrance of Allah. Verily in remembrance of Allah, do hearts find rest.”

The positive effects of religion on coping with grief has also been mentioned in other religions as well, such that Claudia Whitaker in her article entitled “Perinatal grief in Latino parents,” suggested that spirituality is the main constituent of Latino culture and thus has a significant effect on responses to grief. A large number of women (31%) studied in this research interpreted their loss as God's will. As religion and spirituality is a necessity shared between Latino parents, nurses should ask them if they are willing to visit any priests or attend any praying ceremonies for supporting their lost babies.[27]

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding this project and the individual participants for their kind co-operation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuti O, Ilesanmi CE. Experiences and needs of Nigerian women after stillbirth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113:205–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Condon J. The parental–foetal relationship. A comparison of male and female expectant parents. Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;4:217–84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs S, Mazure C, Pregrrson H. Diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Death Stud. 2000;24:185–99. doi: 10.1080/074811800200531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stock S, Goldsmith L, Evanse M, Laing I. Interventions to improve rates of postmortem examination after stillbirth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153:148–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacciatore J. A phenomenological exploration of stillbirth and the effects of ritualization on maternal anxiety and depression Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Human Sciences University of Nebraska. Arizona, ProQuest Information and Learning Company. 2007b [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rådestad I, Steineck G, Nordin C, Sjögren B. Psychological complications after stillbirth-influence of memoriesand immediate management: Population based study. BMJ. 1996;312:1505–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7045.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacciatore J. Effects of support groups on post traumatic stress responses in women experiencing stillbirth. Omega (Westport) 2007;55:71–91. doi: 10.2190/M447-1X11-6566-8042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saflund K, Wredling R. Differences within couples’ experience of their hospital care and well-being three months after experiencing a stillbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1193–9. doi: 10.1080/00016340600804605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts KS. Providing culturally sensitive care to the child bearing Islamic family: Part II. Adv Neonatal Care. 2003;3:250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kersting A, Kroker K, Steinhard J, Lüdorff K, Wesselmann U, Ohrmann P, et al. Complicated grief after traumaticloss: A 14-month follow up study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:437–43. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klass D, Goss R. The politics of grief and continuing bondswith the dead: The cases of Maoist China and Wahhabi Islam. Death Stud. 2003;27:787–811. doi: 10.1080/713842361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Defrain J. Learning about grief from normal families: SIDS, stillbirth, and miscarriage. J Marital Fam Ther. 1991;17:215–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellison CG. Religious Involvement and Subjective Well-being. J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32:80–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson MJ, Marwith SJ, Vanderberg G, Chibnall JT. Psychological and religious coping strategies of mothers bereaved by the sudden death of a child. Death Stud. 2005;29:811–26. doi: 10.1080/07481180500236602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker G, Xander CJ, Blum HE, Lutterbach J, Momm F, Gysels M, et al. Do religious or spiritual beliefs influence bereavement?. A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:207–17. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meryerstein I. A Jewish spiritual perspective on psychopathology and psychotherapy: A Clinician's view. J Relig Health. 2004;43:329–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemati A. Abortion from the perspective of law and jurisprudence. Journal of Fertility and Reproduction. 2005;4:369–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benore ER, Park CL. Death-specific religious beliefs and bereavement: Belief in an afterlife and continued attachment. Int J Psychol Relig. 2004;14:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowchock FS, Lasker JN, Toedter LJ, Skumanich SA, Koenig HG. Religious Beliefs Affect Grieving After Pregnancy Loss. J Relig Health. 2010;49:485–97. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mcintosh DN, Silver RC, Wortman CB. Religion's role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:812–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowchock FS, Ellestad SE, Meador KG, Koenig HG, Hooten EG, Swamy GK. Religiosity is an Important Part of Coping with Grief in Pregnancy after a Traumatic Second Trimester Loss. J Relig Health. 2011;50:901–10. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9528-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts LR, Montgomery S, Lee JW, Anderson BA. Social and Cultural Factors Associated with PerinatalGriefin Chhattisgarh, India. J Community Health. 2012;37:572–82. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thearle MJ, Vance JD, Najman JM. Church attendance, religious affiliation, and responses to sudden infant death, neonatal death, and stillbirth. Omega (Westport) 1995;31:51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann JR, McKeown RE, Bacon J, Vesselinov R, Bush F. Do antenatal religious and spiritual factors impact the risk of postpartum depressive symptoms? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:745–55. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutain R, Miskam HM. Psychosocial impact of perinatal loss among Muslim women. BMC Women's. 2012;12:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langroodi-Jafari MJ. Tehran: Ebnesina; 1965. In the terminology extensive rights. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitaker C, Kavanaugh K, Klima C. Perinatal Grief in Latino Parents. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2010;35:341–5. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181f2a111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]