Abstract

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is effective against chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection and its use is increasing rapidly worldwide. However, it has been established that TDF is associated with renal toxicity in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients, while severe or symptomatic TDF-associated nephrotoxicity has rarely been reported in patients with CHB. Here we present two patients with TDF-associated nephrotoxicity who were being treated for CHB infection. The first patient was found to have clinical manifestations of proximal renal tubular dysfunction and histopathologic evidence of acute tubular necrosis at 5 months after starting TDF treatment. The second patient developed acute kidney injury at 17 days after commencing TDF, and he was found to have membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with acute tubular injury. The renal function improved in both patients after discontinuing TDF. We discuss the risk factors for TDF-associated renal toxicity and present recommendations for monitoring renal function during TDF therapy.

Keywords: Tenofovir, Acute Kidney Injury, Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions, Chronic Hepatitis B, Kidney Tubules

INTRODUCTION

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is an orally bioavailable prodrug of tenofovir [1]. Tenofovir is a nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor that has potent efficacy against retroviruses and hepadnaviruses [2]. TDF was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in 2001, and for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection in 2008. It is now recommended as one of the first-line monotherapies for CHB, and as the ideal agent for CHB patients with lamivudine- or telbivudine-resistant variants [3].

TDF has been found to be associated with dose-dependent renal toxicity in animal studies [4]. The first case of TDF-induced nephrotoxicity in a patient with HIV was reported in 2002 [5]. Since then, numerous case reports of TDF-induced nephrotoxicity in patients with HIV infection have been published, and it is now established that TDF carries a risk of tubular toxicity for HIV-infected patients [6]. The clinical pattern of nephrotoxicity is characterized by slight increases in serum creatinine and decreases in serum phosphate levels occurring 4-12 months after starting the agent. The renal toxicity of TDF appears to manifest as a proximal injury, and the clinical syndrome is a Fanconi-like renal tubular acidosis [7].

Until now, severe or symptomatic nephrotoxicity in CHB patients receiving TDF therapy has been rarely reported [7], and data to date suggest that nephrotoxicity is less common in patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) monoinfection [8]. Several cases of Fanconi syndrome in CHB patients undergoing treatment with TDF have been reported since 2013 [9,10]. One case of TDF-associated Fanconi syndrome and nephrotic syndrome in a patient with HBV monoinfection was reported in 2015 [11]. Here, we report two cases of TDF-associated nephrotocixity. The previously published reports of TDF-associated nephrotoxicity showed no evidence of underlying kidney disease. However, in our cases, there were histopathologic evidences of pre-existing subclinical kidney diseases even though the patients had shown normal kidney function before TDF therapy. Furthermore, our patients showed more severe renal dysfunction after short-term use of TDF.

CASES REPORT

First case (A)

A 76-year-old man with HBV-related liver cirrhosis was admitted for acute renal dysfunction. There was no change in urine output. He was diagnosed with CHB in 1980 and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 2006. He was treated for HCC with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) from November 2007 to October 2013. He was a HBeAg-negative CHB patient and had received TDF 300 mg daily for 5 months starting in July 2013. His underlying conditions included hypertension diagnosed in 2005, and diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism diagnosed in 2010. He received propranolol 10 mg twice a day, gliclazide 60 mg daily, losartan 50 mg daily, and levothyroxine 75 mcg daily. These medications had not been changed for several years, and his underlying conditions had been well controlled. He denied exposure to adefovir, herbal medicine including Aristolochic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), glue sniffing or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs.

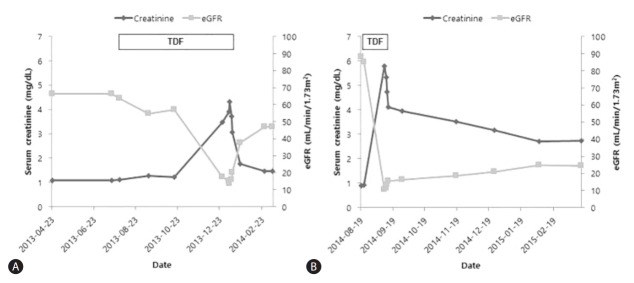

Before the patient started TDF, his serum creatinine was 1.08 mg/dL and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was 66.5 mL/min/1.73m2 (Fig. 1A). Five months after commencing TDF, his serum creatinine level suddenly increased to peak at 4.32 mg/dL and his eGFR was 13.4 mL/min/1.73m2. The fractional excretion of sodium was 5.16%. His serum HBV DNA was 33,600 IU/mL at the time of TDF initiation and within 5 months of TDF treatment was undetectable. Before TDF was started, his serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 87 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 38 IU/L. The serum albumin level was 2.9 mg/dL and prothrombin time was 1.13 (international normalized ratio [INR]). When the patient was admitted because of renal dysfunction, the AST and ALT were slightly increased at 94 IU/L and 48 IU/L, respectively. The serum albumin level was 2.7 mg/dL and prothrombin time was 1.05 (INR).

Figure 1.

Serum creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) before and after discontinuing TDF in (A) Patient A and (B) Patient B. Both patients showed abrupt aggravation of renal function after TDF therapy and improvement following TDF discontinuation.

When the patient’s acute kidney injury (AKI) was discovered, he was evaluated to find the etiology of AKI. He had low serum phosphorus (3.2 mg/dL), low uric acid (3.4 mg/dL), low potassium (2.8 mg/dL) and low total carbon dioxide (16 mmol/L) levels. Although his serum glucose level was less than 200 mg/dL, he had glycosuria (glucose 4+ on a urine dipstick). His urine pH was 5.5, and he had non-albuminuric proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine ratio 1.94, urine microalbumin/creatinine ratio 0.18). Serum protein electrophoresis showed polyclonal gammopathy. Parathyroid hormone and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were within normal range. Neither dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry nor the whole body bone scan were performed. Because of the sudden azotemia with hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis, glycosuria and non-albuminuric proteinuria, we suspected proximal renal tubular damage. Kidney Doppler ultrasonography was performed to exclude other causes of AKI. Both kidneys had normal dimensions (right kidney 9.7 cm, left kidney 9.6 cm) and borderline resistive index (right kidney 0.72-0.73, left kidney 0.66-0.73). No hydronephrosis was detected, and the urinary bladder appeared unremarkable. Because of the patient’s non-albuminuric proteinuria, TDF toxicity was considered the most likely cause of AKI instead of diabetic or hypertensive nephropathy.

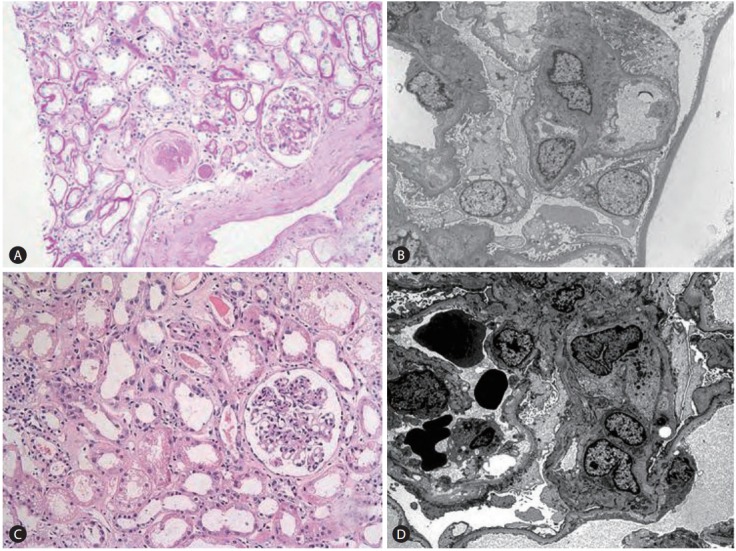

A renal biopsy was done and demonstrated chronic active tubulointerstitial nephritis with focal global sclerosis of glomerulus. (Fig. 2A, B) We concluded that he previously had chronic interstitial nephropathy associated with hypertension, and finally developed acute tubular necrosis after TDF treatment.

Figure 2.

Renal biopsy findings. (A) Patient A, PAS (periodic acid stain) ×200. (B) Patient A, electron microscopy. (C) Patient B, PAS ×200. (D) Patient B, electron microscopy. A renal biopsy of patient A revealed chronic active tubulointerstitial nephritis with focal global sclerosis. A renal biopsy of patient B revealed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), suggestive of hepatitis-B-virus-associated glomerulonephritis, with acute tubular injury.

The patient was subsequently changed to entecavir (ETV) treatment. Two weeks after stopping TDF and starting ETV, his serum creatinine had decreased to 1.76 mg/dL and his eGFR had increased to 37.8 mL/min/1.73m2. Seven weeks after stopping TDF, the serum creatinine had fallen to 1.46 mg/dL and the eGFR had increased to 46.9 mL/min/1.73m2 (Fig. 1A).

Second case (B)

A 50-year-old man with HBV-related liver cirrhosis visited emergency room complaining of lower extremity edema. He also complained decreased urine output. He was diagnosed with HBeAg-positive CHB and HBV-related liver cirrhosis 20 days before the event. The patient had been on TDF 300 mg daily for 17 days. He didn’t have other underlying conditions and denied exposure to adefovir, herbal medicine including Aristolochic acid, NSAIDs, glue sniffing or OTC drugs.

Before starting TDF, his serum creatinine was 0.91 mg/dL and eGFR calculated by MDRD equation was 88.2 mL/min/1.73m2. Seventeen days after starting TDF, his serum creatinine level abruptly increased to peak at 5.79 mg/dL and eGFR was 10.1 mL/min/1.73m2 (Fig. 1B). His serum HBV DNA was greater than 170,000,000 IU/mL before TDF initiation and subsequently decreased after antiviral treatment. At the time of TDF initiation, the serum AST was 69 IU/L and ALT was 25 IU/L. His serum albumin level was 2.6 mg/dL and prothrombin time was 2.03 (INR). When he visited our emergency room, the AST and ALT were 37 IU/L and 25 IU/L, respectively. The serum albumin level was 1.5 mg/dL and prothrombin time was 2.03 (INR).

The patient had high serum phosphorus (6.2 mg/dL), high uric acid (10.9 mg/dL), normal potassium (4.4 mg/dL) and low total carbon dioxide (17 mmol/L) levels. It was not typical for Fanconi-like renal tubular acidosis. In urinalysis, his urine pH was 5.5 and he had heavy proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine ratio 6.72, urine microalbumin/creatinine ratio 3.26) and hematuria. Serum protein electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis showed polyclonal gammopathy. In kidney Doppler ultrasonography, both kidneys had normal dimensions (right kidney 11.22 cm, left kidney 12.02 cm) and normal resistive index (0.63-0.74). Other urinary system revealed no abnormalities.

A renal biopsy was done to find the causes of azotemia. It demonstrated membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), suggestive of HBV-associated glomerulonephritis, with acute tubular injury. There were findings of variation of mitochondrial size due to TDF (Fig. 2C, D). Because the patient denied exposure to NSAIDs, herbs or OTC medications, it is reasonable to explain HBV-associated MPGN caused heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and edema, and tenofovir-associated nephrotoxicity is responsible of acute kidney injury.

He was subsequently switched to ETV treatment and showed improvement of renal function following TDF withdrawal. Two weeks after changing to ETV, his serum creatinine had decreased to 3.95 mg/dL and his eGFR was 16.2 mL/min/1.73m2. Six months after stopping TDF, the serum creatinine had fallen to 2.74 mg/dL and the eGFR had risen to 24.6 mL/min/1.73m2 (Fig. 1B).

DISCUSSION

Renal impairment has been a concern with TDF, based on the evidence from HIV-infected patients receiving TDF; however, to date, the problem appears to be less common in patients infected with HBV [12]. In clinical trials of TDF, creatinine clearance remained stable over 3 years in more than 99% of patients with patients with CHB [13]. In a European multicenter cohort study of TDF for patients with CHB, the proportion of patients with eGFR < 50 ml/min/1.73m2 remained stable throughout the study, and major changes in renal function were minimal [14]. In another TDF study, the median annual change in eGFR was much lower in HBV-infected patients than in HIV-infected patients [15]. Until now, TDF exposure appeared to cause only a modest decrease in eGFR. However, our cases suggest that TDF can cause significant impairment in eGFR. This report makes clear that not only HIV-infected patients, but also CHB patients receiving TDF therapy are at risk of nephrotoxicity.

The renal proximal tubular cell is the main target of TDF toxicity, because the cell expresses membrane transporters that mediate TDF uptake. Current evidence suggests that TDF is toxic to mitochondria [16]. Our first case is similar to the cases of TDF nephrotoxicity in HBV- or, HIV-infected patients in that the patient had clinical manifestations of proximal renal tubular dysfunction and histopathologic findings of acute tubular necrosis. Our second case didn’t show Fanconi-like renal tubular acidosis but there were histopathologic findings of acute tubular injury including mitochondrial size variation. Our cases are somewhat different from the other cases, because there were no findings of mitochondrial depletion, or dysmorphic changes. The biggest difference is that our cases showed pre-existing kidney diseases. In spite of mild form of mitochondrial change, our patients demonstrated more severe renal dysfunction. It is reasonable to explain patients with pre-existing kidney diseases are more vulnerable to kidney injury associated with TDF.

In the previous reports for TDF-associated tubular complications in CHB patients, renal function was fully recovered in all four cases with TDF-associated Fanconi syndrome [9,10]. However, renal function in our cases was not fully recovered to pretreatment level. Pre-existing kidney diseases may contribute to incomplete recovery of renal function. Furthermore, there are some reports of incomplete reversibility of TDF-related nephrotoxicity in HIV-infected patients. Wever et al [17] reported only 42% of patients reached their pre-TDF eGFR.

The risk factors for the development of TDF-associated nephrotoxicity in HIV-infected patients have been identified. They include old age, male sex, low body weight, pre-existing renal impairment, concomitant use of nephrotoxic medications, and comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension [18]. However, TDF-associated nephrotoxicity can occur in patients without obvious risk factors and at highly variable times after the initiation of TDF [7]. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has published official recommendations for TDF use. It recommends that patients who are prescribed TDF and have an eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73m2 should be monitored at least biannually by checking serum creatinine, eGFR, serum phosphorus, and urine for proteinuria and glycosuria [19].

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) also has published guidelines on TDF monitoring for patients with HBV infection. It recommends measuring the baseline serum creatinine and eGFR before starting TDF. High-risk patients are those with decompensated cirrhosis, creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min/1.73m2, hypertension, proteinuria, diabetes mellitus, glomerulonephritis, organ transplant, and concomitant nephrotoxic drugs. EASL also recommends monitoring the serum creatinine, eGFR, and serum phosphate levels in all TDF-treated patients every 1-3 months during the first year of treatment and every 3-6 months thereafter, depending on the patient’s kidney risk profile [20]. Because TDF is recommended as a first-line therapy for CHB infection, it will be prescribed for a prolonged period to many patients. However, the long-term effects of TDF on kidney function are not yet certain. Close observation and monitoring for kidney function must be ongoing.

Furthermore, the short-term safety of TDF for CHB patients with underlying kidney diseases still needs further study, as shown in our cases. In HIV-infected patients, TDF-associated nephrotoxicity is not always a late onset complication. In a retrospective study of TDF-associated tubular complications in patients with HIV infection, 3 of 13 patients had been treated within 6 months when AKI occurred [21]. Comparing our cases to previous reports, it is possible that nephrotoxicity was exaggerated by older age, pre-existing kidney disease or ethnic difference. In conclusion, short-term safety as well as long-term safety of TDF on kidney function in CHB patients with pre-existing kidney diseases should be studied further.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the report of rare cases of severe and symptomatic renal dysfunction in patients who were being treated with TDF for CHB infection. The first patient had a history of hypertension and hypertension-associated chronic interstitial nephropathy, and the second patient had HBV-associated MPGN. A short period of time after starting TDF, their serum creatinine level abruptly increased, and they were ultimately diagnosed with acute tubular injury as a result of TDF treatment. In other words, both cases had pre-existing subclinical kidney diseases before TDF therapy. Therefore, when we start TDF we must evaluate the patients’ kidney status by not only serum creatinine or eGFR but also proteinuria, hematuria or glycosuria to find out the patients with subclinical kidney diseases. Furthermore, for the high-risk patients including who have subclinical kidney diseases, it is necessary to monitor urinalysis with routine check-up. Because presence of proteinuria or hematuria might be the clue for vulnerability to kidney injury associated with TDF. Also follow-up is needed more frequently than 1-3 months in such patients as suggested by EASL guideline.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number : HI16C1074).

Abbreviations

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CHB

chronic hepatitis B

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ETV

entecavir

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IDSA

Infectious Diseases Society of America

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MDRD

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- MPGN

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OTC

over-thecounter

- PEI

percutaneous ethanol injection

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- TACE

transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

- TDF

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gallant JE, Deresinski S. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:944–950. doi: 10.1086/378068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearny BP, Flaherty JF, Shah J. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:595–612. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuen MF, Lai CL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B: evolution over two decades. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Rompay KK, Durand-Gasselin L, Brignolo LL, Ray AS, Abel K, Cihlar T, et al. Chronic administration of tenofovir to rhesus macaques from infancy through adulthood and pregnancy: summary of pharmacokinetics and biological and virological effects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3144–3160. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00350-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhelst D, Monge M, Meynard JL, Fouqueray B, Mougenot B, Girard PM, et al. Fanconi syndrome and renal failure induced by tenofovir: a first case report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:1331–1333. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.36924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:773–780. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontana RJ. Side effects of long-term oral antiviral therapy for hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S185–S195. doi: 10.1002/hep.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pol S, Lampertico P. First-line treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir or tenofovir in ‘real life’ setting: from clinical trials to clinical practice. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2012.01602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gracey DM, Snelling P, McKenzie P, Strasser SI. Tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome in patients with chronic hepatitis B monoinfection. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:945–948. doi: 10.3851/IMP2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viganò M, Brocchieri A, Spinetti A, Zaltron S, Mangia G, Facchetti F, et al. Tenofovir-induced Fanconi syndrome in chronic hepatitis B monoinfected patients that reverted after tenofovir withdrawal. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:600–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang HS, Park CW, Song MJ. Tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome and nephrotic syndrome in a patient with chronic hepatitis B monoinfection. Hepatology. 2015;62:1318–1320. doi: 10.1002/hep.27730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:107–119. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09354562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132–143. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampertico P, Soffredini R, Viganò M, Yurdaydin C, Idilman R, Papatheodoridis G, et al. 525 Tenofovir monotherapy for naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B: a multicenter European study in clinical practice in 302 patients followed for 30 months. J Hepatol. 2012;56(Suppl 2):S208. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauss S, Berger F, Filmann N, Hueppe D, Henke J, Hegener P, et al. Effect of HBV polymerase inhibitors on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1235–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Fernandez B, Montoya-Ferrer A, Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Izquierdo MC, Poveda J, et al. Tenofovir Nephrotoxicity: 2011 Update. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011:354908. doi: 10.1155/2011/354908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wever K, van Agtmael MA, Carr A. Incomplete reversibility of tenofovir-related renal toxicity in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:78–81. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d05579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tourret J, Deray G, Isnard-Bagnis C. Tenofovir effect on the kidneys of HIV-infected patients: a double-edged sword? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1519–1527. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, Boydstun II, Ahuja TS, Rodriguez RA, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1559–1585. doi: 10.1086/430257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Association For The Study Of The Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herlitz LC, Mohan S, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati VD, Markowitz GS. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity: acute tubular necrosis with distinctive clinical, pathological, and mitochondrial abnormalities. Kidney Int. 2010;78:1171–1177. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]