Abstract

Background

For selected individuals with type 1 diabetes, pancreatic islet transplantation (IT) prevents recurrent severe hypoglycemia and optimizes glycemia, although ongoing systemic immunosuppression is needed. Our aim was to explore candidates and recipients' expectations of transplantation, their experience of being on the waiting list, and (for recipients) the procedure and life posttransplant.

Methods

Cross-sectional qualitative research design using semistructured interviews with 16 adults (8 pretransplant, 8 posttransplant; from 4 UK centers (n = 13) and 1 Canadian center (n = 3)). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and underwent inductive thematic analysis.

Results

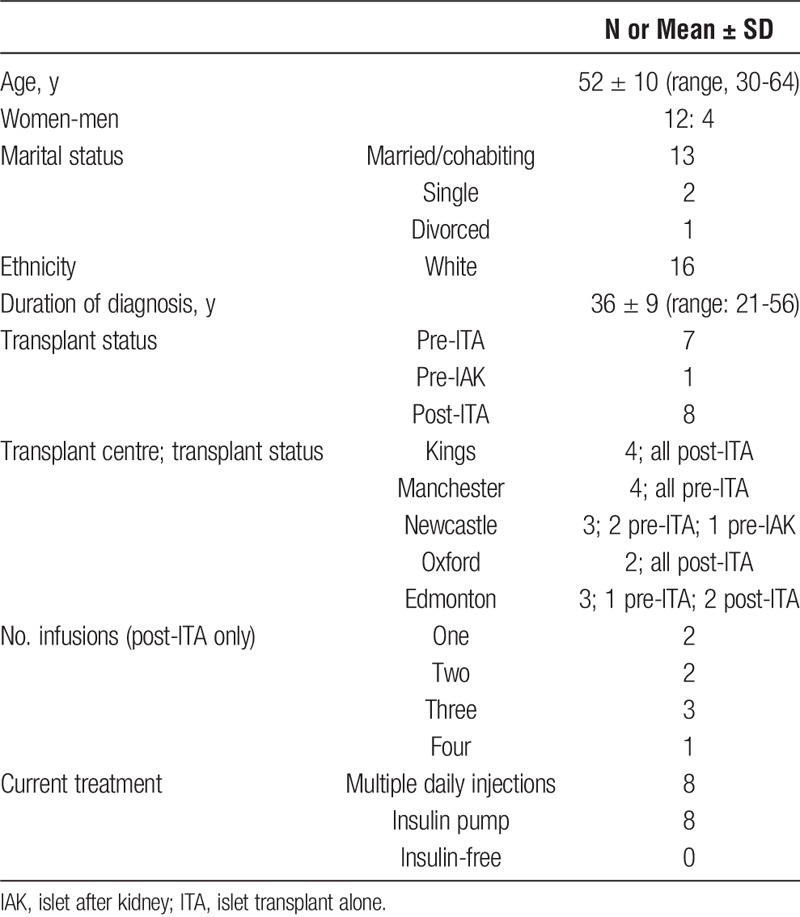

Interviewees were aged (mean ± SD) 52 ± 10 years (range, 30-64); duration of diabetes, 36 ± 9 years (range, 21-56); 12 (75%) were women. Narrative accounts centered on expectations, hopes, and realities; decision-making; waiting and uncertainty; the procedure, hospital stay, and follow-up. Expected benefits included fewer severe hypoglycemic episodes, reduced need for insulin, preventing onset/progression of complications and improved psychological well-being. These were realized for most, at least in the short term. Most interviewees described well-informed, shared decision-making with clinicians and family, and managing their expectations. Although life “on the list” could be stressful, and immunosuppressant side effects were severe, interviewees reported “no regrets.” Posttransplant, interviewees experienced increased confidence, through freedom from hypoglycemia and regained glycemic control, which tempered any disappointment about continued reliance on insulin. Most viewed their transplant as a success, though several reflected upon setbacks and hidden hopes for becoming “insulin-free.”

Conclusions

Independently undertaken interviews demonstrated realistic and balanced expectations of IT and indicate how to optimize the process and support for future IT candidates.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune condition characterized by absolute insulin deficiency caused by immunological damage to the β cells in the pancreas. It can occur at any age but approximately half of cases are diagnosed in children and adolescents. Acutely, the immediate life-threatening consequences of insulin deficiency are managed with exogenous insulin, delivered by multiple daily injections or an insulin pump. Thereafter, effective daily blood glucose management is critical to avoid both acute complications (eg, severe hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis) and long-term complications (eg, microvascular disease of the kidneys, eye, and nerves; ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease). Thus, the reality of living with T1D is a challenging and relentless daily burden involving continual attention to blood glucose management, with titration of insulin doses, according to food intake and physical activity, and self-monitoring of blood glucoses levels. Susceptibility to severe hypoglycemia increases with age and duration of T1D,1 and the ability to recognize warning symptoms (“awareness”) of hypoglycemia diminishes placing the person at a 6-fold increased risk of severe hypoglycemia.2

Currently, successful β cell replacement through whole pancreas or isolated islet cell transplantation (IT) is the only therapy that offers a minimally invasive procedure, which optimizes glycemia reproducibly, with absolute prevention of recurrent severe hypoglycemia, and restoration of hypoglycaemic warning signs.3 Since the seminal success in Edmonton, Canada,4 more than 1000 people with T1D have received deceased donor pancreatic islet allografts worldwide.5 Although safer and less invasive than whole pancreas transplantation,6 there is attrition in graft function over time; at least 50% of transplant recipients return to insulin injections by 5 years.7,8 A strict ongoing systemic immunosuppression medication regimen is required to minimize likelihood of rejection of the transplanted islet cells. Thus, recipients need to remain vigilant for signs of graft failure, and frequent clinic appointments and regular blood glucose self-monitoring remain the norm posttransplant.9

Some commentaries have raised concerns about whether current benefits of IT truly outweigh the risks.10,11 Furthermore, the paucity of data on recipients' expectations and satisfaction has been highlighted by both the US Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality12 and UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.13 Increasingly, the success of biomedical interventions is assessed not only in terms of biomedical outcomes (such as those noted above) but also in terms of their impact on psychological or “patient-reported” outcomes. Our systematic review found that IT potentially improves psychological well-being, diabetes-specific quality of life, fear of hypoglycemia, and generic health status.14 However, we concluded that existing questionnaires are unlikely to capture fully the impact and experience of undergoing IT, because they are not necessarily designed or selected to reflect the full experience for the person with T1D.14 If risks and benefits of IT are to be fully understood, a truly person-centered approach is needed to understand the individual's full experience of the IT process, and optimize positive impact for recipients. This is missing from published literature.

Only 2 qualitative studies have previously explored the experiences of IT recipients. The first was outlined briefly in an article focused almost entirely on quantitative outcomes.15 The second was also a mixed methods study, and demonstrated both the positive impact of IT on personal control over social life situation, and the recipients' experience of IT as worthwhile.16 To our knowledge, no study to date has explored expectations and the process of undergoing IT from the individual's perspective. Thus, our aim was to explore the expectations of people undergoing IT, how they weighed up advantages and disadvantages during the decision-making process, their experiences of being on the waiting list, the procedure itself and life posttransplant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

All IT candidates and recipients at 4 UK transplant centers (King's, Manchester, Newcastle, and Oxford) were invited to participate. Strict selection criteria for the UK IT program included: 2 episodes or more of severe hypoglycemia requiring third-party intervention over 2 years and impaired hypoglycemia awareness (Clarke questionnaire17 score ≥4), despite optimized conventional diabetes therapy. Risks and benefits of the procedure including alternative interventions were discussed with all potential transplant candidates, and all were assessed by a clinical psychologist before transplantation, with the main aim of identifying those who might require additional posttransplant support.

Due to the small numbers of UK transplants conducted at that time, and to gain an international perspective, a purposive sample of 6 participants was recruited from Edmonton, Canada: 3 pretransplant and 3 posttransplant, considered by their clinicians to have experiences that would enrich our study. Criteria for accessing the Canadian IT program were similar to the United Kingdom.

Posttransplant, immunosuppression therapy comprised tacrolimus/sirolimus or tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil.

Interview Schedule

Using a semistructured interview schedule, we invited participants to explore their expectations and experiences in response to the following open questions: What did your doctor tell you to expect from your transplant? How much were you involved in deciding whether or not to have this sort of transplant? How do you feel about your transplant now? Posttransplant respondents were also asked: How satisfied are you with your transplant? Has the transplant met your expectations? If so, in what ways? Can you tell me about the immunosuppression drugs that you have to take?

Procedure

The UK Medical Research Ethics Committee gave ethical approval, with site-specific approvals at each UK center; the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board–approved interviews at Edmonton. Each participant provided informed written consent.

In the United Kingdom, interviews were conducted in the diabetes centers by 2 psychologists (rotating between J.S., A.W., and M.D.R.), all experienced in diabetes research and independent of the transplant teams. Two of the 13 participants were interviewed at home, accompanied by their husbands. For logistical reasons, interviews with participants based in Edmonton were conducted by telephone or “Skype.” Interviews typically lasted 90 minutes though half of that time explored quality of life (not presented here). All interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed, though 3 ‘Skype’ recordings were of poor quality, so those participants' data were subsequently excluded.

Analysis

We used inductive thematic analysis and extracted quotes to illustrate themes. In contrast to deductive thematic analysis, where hypotheses are imposed upon the data, in inductive thematic analysis, the data are relied upon for generating the structure of the findings.18 This is the ideal approach when exploring new topics. Inductive thematic analysis involves several phases: familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes among codes, defining and reviewing themes to produce a final structure. A “theme” constitutes a pattern of explanation given by more than 1 interviewee. Thematic analysis has been described as a tool that underpins several qualitative research methods, such as grounded theory and interpretative phenomenological analysis but is free from the theoretical constraints and assumptions imposed by those methods.18 More recently, thematic analysis has been considered as a valuable method in its own right.19

In the first stage, between interviews, 1 psychologist (M.D.R.) read each transcript and proposed themes for each participant, making notes about codings.20 These were discussed by all 3 psychologists. In the second stage, 1 psychologist (A.W.) read repeatedly all transcripts and notes, together constituting the data corpus. At the end of thematic analysis, after repeated reading of the data corpus, no new themes were emerging. In the final stage, further checks (by J.S. and M.D.R.) confirmed no additional recurring themes.

An anonymized coding system—identity number (X), sex (M/F), transplant status (pre/post), country (UK/Canada)—is used to identify the source of each quote (in parentheses after each quote). Study center was excluded to preserve interviewee anonymity. Because most physicians were male and most transplant co-ordinators female, participants' quotes were modified so that all physicians are referred to as males and all co-ordinators as females. Thus, professionals' anonymity is preserved in the case of exceptions to this rule.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 16 participants (13 from the United Kingdom, 3 from Canada). Twelve were women, all were white, and 13 were married/cohabiting. The mean age of interviewees was 52 years, and they had been living with T1D for a mean of 36 years. Eight were interviewed pretransplant and 8 posttransplant, of whom most had received at least two separate infusions of islet cells. Half of the participants were using an insulin pump. Of the posttransplant interviewees, none was insulin-free at the time of interview.

TABLE 1.

Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics (N = 16)

Expectations, Hopes and Realities of IT

Research Participation: Excitement and Altruism

Interviewees described involvement in the transplant program as exciting, “a medical adventure because it's research” (9FpostUK), or expressed altruistic sentiments, “I did hope that, even if it didn't work on me, that… it might help somebody else” (12FpostUK) (Table 2).

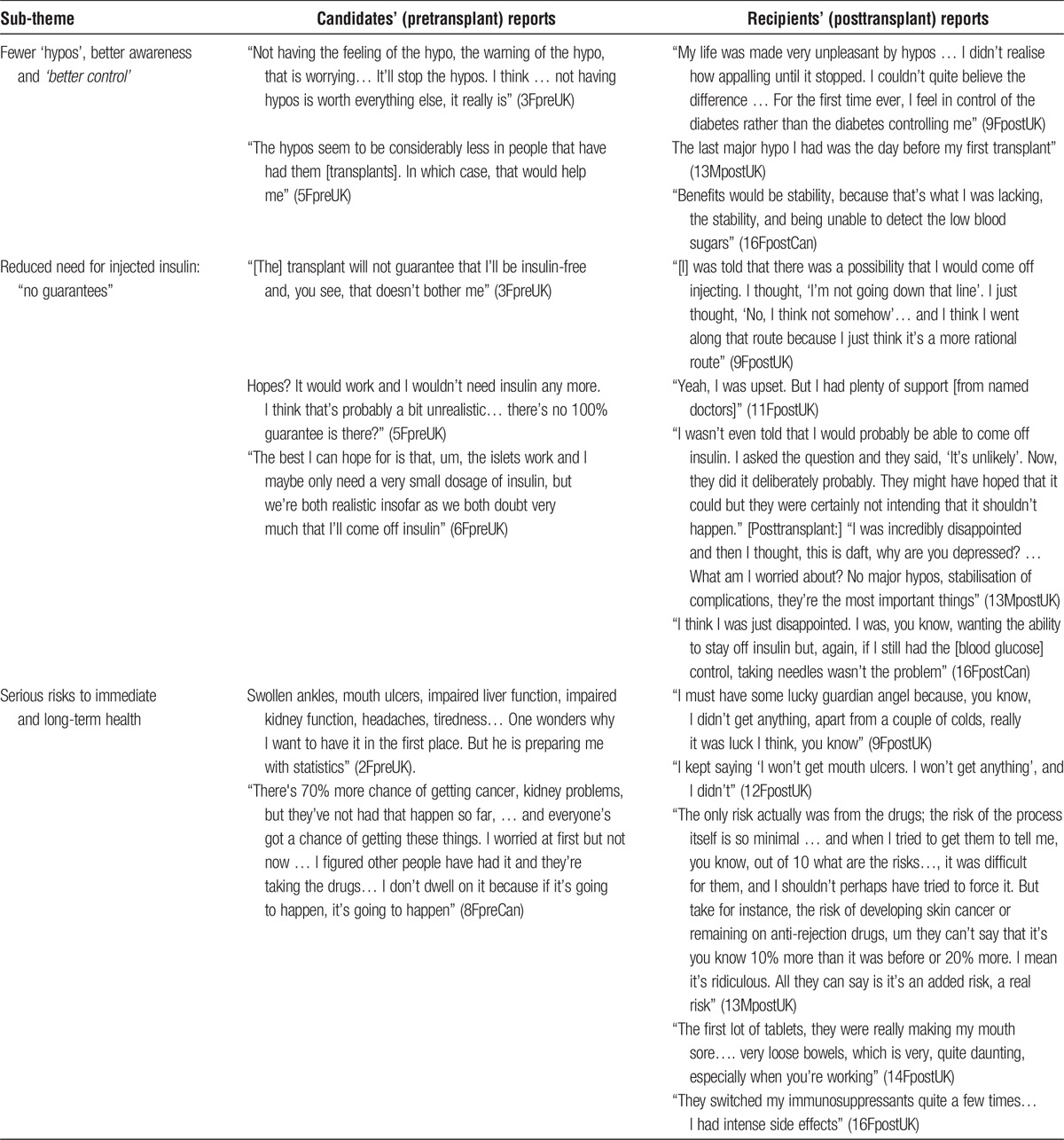

TABLE 2.

Expectations, hopes, and realities

Fewer “Hypos”, Better Awareness and “Better Control”

Candidates were clear about why they wanted the transplant. Their reasons included recurrent unpredictable severe hypoglycemia (“hypos” or “lows”) and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia, which limited their quality of life; they referred to wanting “better control” or “greater stability” of blood glucose. Food and insulin impacted unpredictably on their blood glucose levels pre-IT. Post-IT, severe hypoglycemia was reduced or eliminated, at least short term, and awareness of hypoglycemia regained. However, the benefits did not endure for everyone. The earliest recipient interviewed had received 3 infusions but was experiencing frequent hypoglycemia again.

Reduced Need for Injected Insulin: “No Guarantees”

Interviewees were accustomed to injecting insulin, and most did not object to continuing to do so. Becoming insulin-independent was a pre-IT hope often tempered by realism and “no guarantee” clauses, which endured post-IT. Nonetheless, some retained hidden hopes to become insulin-independent and others had high expectations of “not having hypos, not being on insulin, being able to eat more or less what I wanted… everything about life would be better” (12FpostUK). The idea of the transplant “working” was tied up with hopes of insulin-independence. Even a small chance of an insulin-free period, no matter how short, went into the decision-making equation, even if it was then rejected as unrealistic.

Post-IT, some had been temporarily insulin-free, although all were using insulin pumps or injections when interviewed. They could be “disappointed” or “upset,” particularly if denied another transplant, yet spoke of support from the transplant team and how they reframed their disappointment to focus on outcomes achieved, for example, fewer severe hypoglycaemic events, blood glucose stability.

“Not Being Diabetic”

Interviewees expressed the hope that having IT would mean they no longer had diabetes: “I'd be nondiabetic for a time… I would welcome the break… I'm very aware that at best I might get 5 years, and then …be diabetic again, but …all the rest of it would be marvellous” (2FpreUK). Indeed, 1 posttransplant interviewee had declared to the UK Driving and Vehicle Licensing Authority that she no longer had diabetes but had to reverse that when the need for exogenous insulin returned.

Preventing or Halting Complications

Interviewees mentioned that pre-IT, they had hoped the transplant would have the benefit of preventing or halting progression of complications, particularly retinopathy. In the single case of islet after kidney, the interviewee indicated that the clinician was hoping “to protect my kidney for as long as possible”. Posttransplant, the only person who mentioned complications said that his had stabilized.

Benefits for Psychological Well-Being

The hopes of almost all IT recipients were realised, initially at least, with noticeably improved psychological well-being and energy: “I actually had energy… I didn't feel so irritable” (9FpostUK). Another commented, “not embarrassing yourself at work or [with] friends, you know. That always bothered me… I don’t have any problems with lows right now. So, yes, more confidence and less worries” (15MpostCan).

Serious Risks to Immediate and Long-Term Health

Overall, risks were less clearly recalled and described than benefits and were often considered unlikely. For people several years post-IT, the risks seemed to have passed. Interviewees were aware of, and some were fatalistic about, the possibility of immunosuppressant side effects. After a number of straightforward infusions, interviewees tended to place more emphasis on risk of side effects than on the procedure. Side effects ranged from severe, “I lost the end of my tongue actually from a terrible ulcer” (10FpostUK), to minor, “a couple of infections” or none, in which case, participants described themselves as “lucky” or having willpower.

Decision-Making Pretransplant and Dealing With Risks Posttransplant

Informed Decision-Making

Clinical teams were reported as being “very open about the things that could happen” (3FpreUK), describing the risks fully, although this could be seen as a necessary strategy to avoid comeback. Although some could not see the point of receiving detailed information early on, before “suitability” was established, others were determined to seek all available information to make “an informed decision”. Interviewees emphasized that the decision was theirs (Table 3).

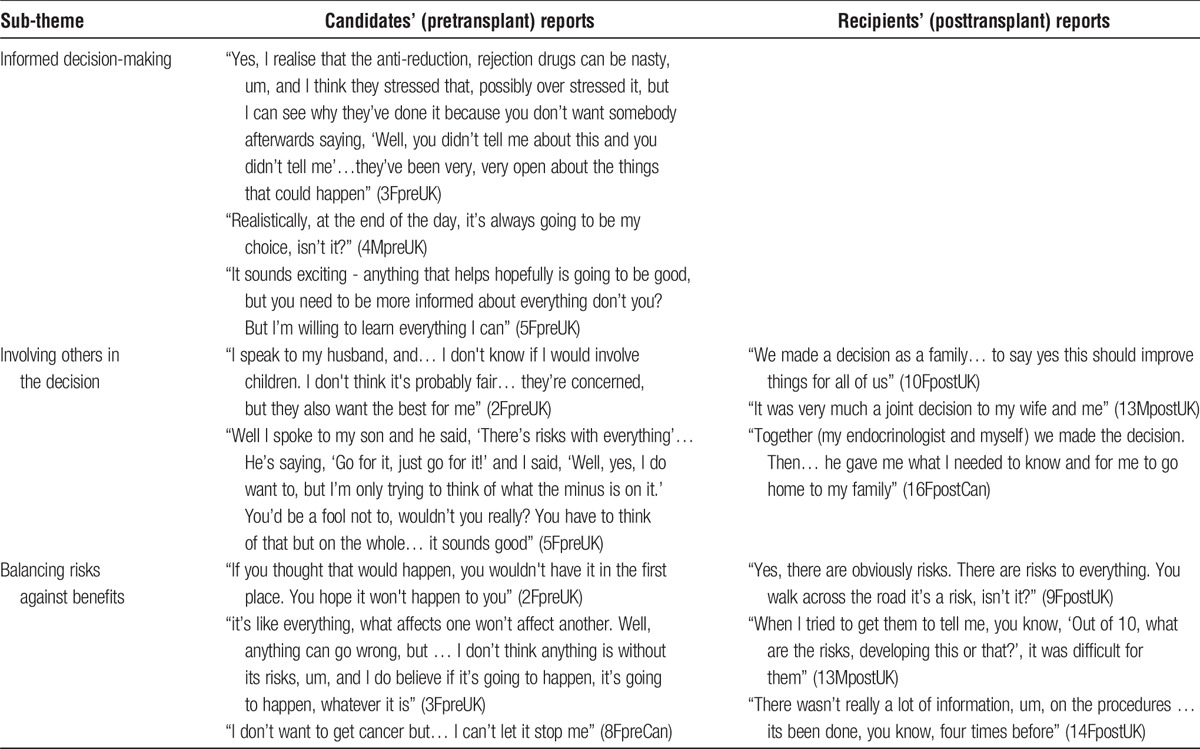

TABLE 3.

Decision-making pre-transplant and dealing with risks posttransplant

Involving Others in the Decision

Family involvement in decision-making varied: most discussed it with family but some had already decided with their clinician. Typically, individuals had to temper their own and their family's enthusiasm.

Balancing Risks Against Benefits

Focusing largely on the transplant itself, interviewees balanced perceived benefits against risks, with some wishful thinking. Earlier UK IT recipients recalled the lack of certainty clinicians had expressed about the risks involved, leaving them worried, partly due to the novelty of the procedure. Once they had decided on IT, coping strategies served to reduce anxiety: interviewees tended to “think on the positive side” or consider risks as a matter of chance or fate, which did not worry them; they commonly put risks to one side; or they managed expectations, believing the worst that could happen was that the procedure did not “work,” and concluding “Well, I wouldn't be any worse off, would I, than I am now?” (5FpreUK). Post-IT, after a number of straightforward infusions, recipients emphasised the risk of the immunosuppression side-effects rather than the procedure.

With regard to ongoing immunosuppression required post-IT, the reality was that some experienced health problems. However, none of the candidates or recipients spoke of it in terms of swapping 1 treatment (insulin) for another (immunosuppression). Even those who had experienced several setbacks reflected that there was no permanent damage: “I tried something and it didn’t work and that’s pretty much it” (16FpostCan).

Waiting and Uncertainty

Pre-transplant Investigations: Not Building up Your Hopes

During pre-IT investigations, participants did not want to build up their hopes. The time commitment for pre-IT investigations was considerable and this extended period of uncertainty could be stressful (Table 4).

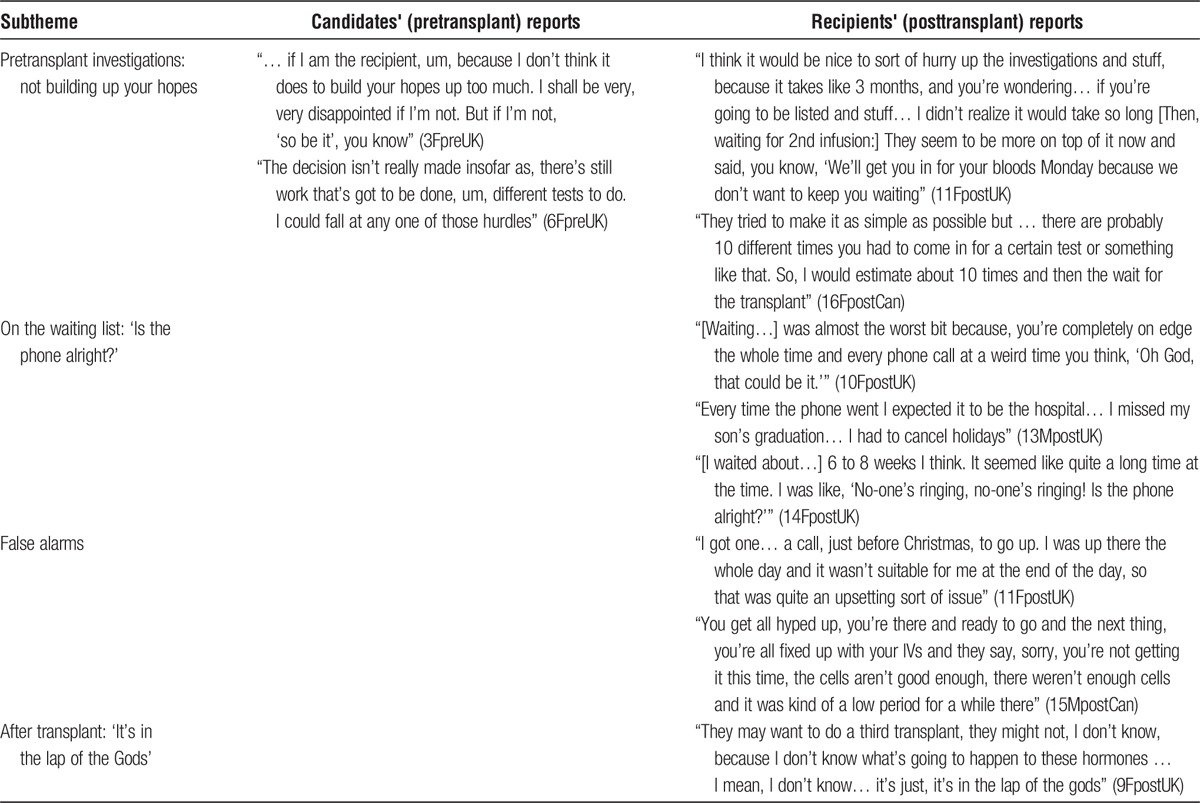

TABLE 4.

Waiting and uncertainty

On the Waiting List: “Is the Phone Alright?”

The wait for a suitable donor was often lengthy, stressful and limited interviewees' ability or willingness to travel. Post-IT interviewees described this as the most difficult part, becoming increasingly anxious when there was no call from the centre.

False Alarms

When the call came, the islet preparation could prove unsuitable. Participants experienced at least one false alarm, which could be “upsetting” or depressing.

After Transplant: “It's in the Lap of the Gods”

Even when the transplanted islets produced insulin, there remained uncertainty about the future, whether they would remain insulin-independent and whether or not subsequent transplants would be needed.

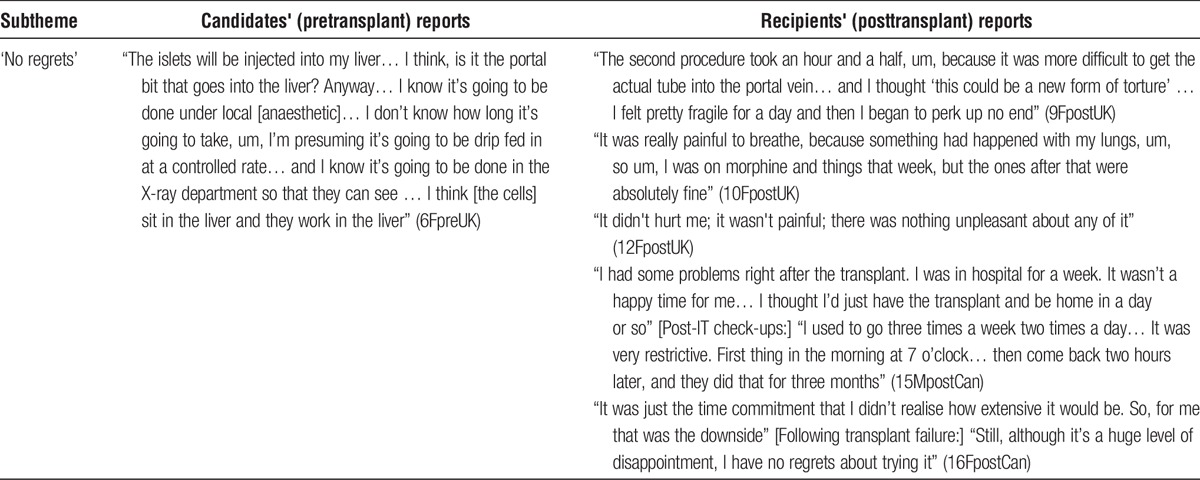

The Procedure, Hospital Stay and Follow-Up: “No Regrets”

Pretransplant interviewees thought they had a clear understanding of the procedure and described it in their own words (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

The procedure, hospital stay, and follow-up

When the procedure went well, it was mostly described as quick, pain-free and unproblematic: “it took half an hour, and that was extraordinary” (9FpostUK). However, some experienced “painful” complications.

Recovery was usually swift but when the procedure was not straightforward, hospital stays were longer than expected. In the United Kingdom, because it was a novel procedure, the hospital stay was routinely longer than that in Edmonton.

Posttransplant check-ups were a considerable commitment, and particularly burdensome if living far away from the centre. Some said they had not realized “how extensive it would be” (16FpostCan).

Balancing the outcomes against immunosuppressant side effects, the procedure and its eventual outcome, as well as the time commitment, most reported “no regrets” about “going for it”.

DISCUSSION

This is the first in-depth qualitative study investigating the expectations and experiences of adults with T1DM undergoing IT in the United Kingdom, without which meaningful quantitative evaluation of IT is not possible. Although several quantitative investigations have evaluated impact on health and well-being,14 our study represents the first to explore expectations, hopes, decision-making, and outcomes in the recipients' own words.

Although none of the post-IT participants were insulin-free at the time of interview, insulin independence has never been promoted actively as a goal of the UK islet transplant program. All interviewees reported severe recurrent and unpredictable hypoglycemia pretransplant and most expected or hoped for modest improvements afterwards. Consistent with published quantitative findings,14 this study confirmed that, posttransplant, interviewees reported being pleased with various combinations of improved glycemia, regained awareness of hypoglycemia, and, most commonly, reduced frequency or severity of hypoglycemia. This had “life-changing” psychological benefits, improving well-being, confidence, and quality of life.

Overall, in contrast to the post-IT participants (early recipients), transplant candidates reported realistic expectations, especially concerning “coming off insulin.” Physicians counsel about this possibility pretransplant.10 Although transplant teams largely managed expectations appropriately, many interviewees retained hidden hopes (reportedly shared by some physicians) of being among the minority to remain insulin-free at 5 years. This natural tendency toward optimistic bias needs to be recognized and managed by transplant teams. Furthermore, recipients need support to develop strategies to cope with disappointment at any stage, including not being “suitable,” lengthy wait for donor organ, “false alarms,” graft rejection, or function loss. Even though transplant teams are now careful not to frame IT as a potential cure, the lay belief endures, meaning that extra care is needed to ensure that all professionals give the same cautious message. It has been acknowledged elsewhere that individuals' goals and expectations impact on their perceptions of IT success.10

Whether or not a period of insulin independence had been experienced, coping with any disappointment when insulin became necessary was addressed by reframing the benefits to focus on blood glucose stability. A determination to remain positive, combined with the negative consequences of transplantation, has been noted elsewhere.21,22 Whereas kidney transplantation is life-saving and success is dichotomous (ie, independence from dialysis or not), IT is life-changing and offers several potential benefits. Thus, whereas coping with disappointment and avoiding depression would be difficult for kidney transplant recipients,21 it may be easier for IT recipients who can focus on other benefits.

Coping strategies were also apparent in participants' descriptions of how they dealt with the uncertainty of life “on the list,” with emphasis placed on luck, fate, chance, and willpower. Such observations have been made, where transplant recipients used external loci of control to manage uncertainties and organ rejection.23 Evidence from kidney transplant research suggests that belief in chance or fate may be a reasonable coping mechanism, because those with greater perceptions of internal or personal control were most depressed when the transplant failed.24,25

Given the realities of the transplant process, uncertainty for those on the waiting list is unavoidable. Candidates need to be prepared for the significant time commitment involved in medical investigations. Pre-IT and post-IT investigations need to be conducted efficiently, with appreciation that each individual balances this against personal commitments, including family and employment. A successful transplant program needs to prepare participants fully for the risks involved—with sensitivity to how much information potential candidates may or may not want before their “suitability” as a candidate is confirmed—both to physical health and psychological well-being, and to detect problems and provide support at any stage. Timely and efficient investigations, psychological assessments and a responsive clinical team, who provide consistent messages, are key ingredients for ensuring best possible care for IT recipients and their families during this time of high hopes and unavoidable uncertainties. Our findings have informed the published Diabetes UK patient guide,26 particularly ensuring that information about risks of comorbidities and anticipated frequency of hospital attendances are explicit.

Unsurprisingly, the decision to join the transplant waiting list was made by the individual with support from, and information sharing with, their clinical team. Family involvement was actively encouraged but the individual decided when to involve them and often needed to counter the families' enthusiasm by advocating information-seeking about the risks and realities to reach a rational decision.

Our study has several limitations, particularly relating to the sample. The UK sample size was small but included all IT recipients and candidates (those on the waiting list) at the time; the Canadian purposive sample was added to maximize confidence that UK experiences were similar to those in a more established program. The selective and subjective sampling of Canadian participants and the fact that several recordings were of poor quality is a limitation. However, we noted considerable heterogeneity of experience among the Canadian participants, and their inclusion was only ever intended to augment the sample size and validate the UK experience, this being the main focus of the study. This remains the largest qualitative study of IT conducted to date. Qualitative studies cannot claim to be representative but after repeated reading of the data corpus, no new themes emerged, and we were satisfied that data saturation had been achieved. We had a unique opportunity to understand the experiences of IT recipients and candidates at an early stage of the UK program. There was remarkable commonality between the accounts of United Kingdom and Canadian participants. This may be explained by the fact that there is still a small number of IT centers, with close collaboration and intercenter support internationally. Although only half the participants were posttransplant, which limits the findings about posttransplant status, there was strength in this approach because the experience of being on the waiting list was current for half the participants, not relying on retrospection or subject to potential reframing. The diversity of centers (4 United Kingdom and 1 Canada) can be considered a strength, whereas the unintentional preponderance of whites and women raises some concerns for generalizability. The IT program itself has a clear bias toward female recipients, given the need for relatively low body weight and modest insulin requirements. It is noteworthy that the only other qualitative study also includes more women than men.16 It is possible that IT recipients from other ethnic groups may be more trusting and less willing to ask questions, particularly if that might be viewed as challenging authority.27

Another limitation is that many early recipients had achieved “celebrity status” in the diabetes world and, clearly, all were grateful to their clinicians for the opportunity to be among the first to receive an IT. Their many press interviews may have led to some rehearsed responses and a certain reticence to highlight any negative aspects of IT. To maximize the likelihood of unfettered and balanced feedback, we used 3 strategies: (1) the psychologists who conducted the interviews were independent of the clinical centers and direct care of the transplant recipients; (2) participants were assured of anonymity, with any identifying words removed from the quotes used; (3) we tapped into the participants' altruistic tendencies and support for research by assuring them that we were interested in any experiences/comments that would help the centers to improve the islet transplant experience for future recipients. Before joining the IT waiting list, prospective candidates were screened for psychological stability, meaning that extreme emotional reactions or unrealistic expectations were unlikely. Further research with a larger sample from the more established UK program, and considering the longer-term outcomes, is now warranted to corroborate or update these findings, especially since the introduction of the new Diabetes UK patient guide to IT.26

This independently undertaken qualitative study sought to capture the breadth and depth of experience of those undergoing IT. It provides insights into both common and individualistic expectations and experiences, offering clinicians the opportunity to learn how to optimize the process, assessment, and support for future IT candidates. The study also provides a person-centered evidence base for developing and selecting robust questionnaires for quantitative assessment of patients' expectations, experiences and satisfaction with IT, alongside biomedical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the people awaiting IT or having received IT who participated in this study, for generously sharing their time and insights.

The authors also thank the transplant co-ordinators and other center staff who helped with participant recruitment: Edmonton: Parastoo Dinyari, Sharleen Imes, Lana Toth, Andrew Malcolm, Angela Koh; King's: Andrew Pernet; Manchester: Sarah Pendlebury with infrastructural support from the Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre; Newcastle: Julie Wardle, Charlotte Gordon; Oxford: Anne Brownson, Neil Walker.

The authors thank representatives from all clinical centers within the UK Islet Transplant Consortium who supported, reviewed, and approved the work reported: Richard Smith (Bristol); Shareen Forbes (Edinburgh); Pratik Choudhary (King's College London); Gareth Jones and Miranda Rosenthal (Royal Free London).

Footnotes

Published online 21 April 2016.

Diabetes UK funded this work as part of the UK Islet Transplant Consortium project grant “Establishment of optimized biomedical and psychosocial measures to determine overall outcomes in islet transplant recipients” (no: BDA 06/0003362). Diabetes UK played no role in the preparation of this manuscript.

J.S. and M.D.R. disclose that AHP Research received consultancy fees from Astellas Pharma for an unrelated project to advise on the use of patient-reported outcome measures for the evaluation of antirejection medications used in transplantation. The remaining authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

J.S. and J.A.M.S. conceived the qualitative study as part of the UK Islet Transplant Consortium research programme. J.S., J.A.M.S., A.W., and M.D.R. designed the interview schedule. J.S., M.D.R., and A.W. conducted the interviews. M.D.R. conducted preliminary analyses, and A.W. conducted in-depth analyses of the full data corpus. J.S. and M.D.R. each reviewed a selection of transcripts to verify the in-depth analyses. J.S. and A.W. prepared the first draft of this article. All other authors were involved in participant recruitment and management, contributed to revisions, and approved the final version of the article. J.S. and A.W. guarantee the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. The DCCT Research Group. Epidemiology of severe hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. Am J Med 1991; 90: 450– 459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gold AE, MacLeod KM, Frier BM. Frequency of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type I diabetes with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 1994; 17: 697– 703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005; 54: 2060– 2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 230– 238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Kort H, de Koning EJ, Rabelink TJ, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. BMJ. 2011; 342: d217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robertson RP, Davis C, Larsen J, et al. Pancreas and islet transplantation for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000; 23: 112– 116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leitão CB, Cure P, Tharavanij T, et al. Current challenges in islet transplantation. Curr Diab Rep. 2008; 8: 324– 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vantyghem M-C, Kerr-Conte J, Arnalsteen L, et al. Primary graft function, metabolic control, and graft survival after islet transplantation. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32: 1473– 1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griva K, Newman S. Transplantation. In: Ayers S, Baum A, McManus C, editors. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Senior P. Patient selection and assessment: an endocrinologist's perspective. In: Shapiro AMJ, Shaw J, editors. Islet Transplantation and Beta Cell Replacement Therapy. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harlan DM, Kenyon NS, Korsgren O, et al. Current advances and travails in islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2009; 58: 2175– 2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piper M, Seidenfeld J; United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Allogeneic pancreatic islet cell transplantation for type 1 diabetes mellitus: Interventional procedure guidance [IPG257]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg257. NICE; 2008. (accessed: 30 September 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Speight J, Reaney M, Woodcock A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following islet cell or pancreas transplantation (alone or after kidney) in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2010; 27: 812– 822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poggioli R, Faradji RN, Ponte G, et al. Quality of life after islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006; 6: 371– 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Häggström E, Rehnman M, Gunningberg L. Quality of life and social life situation in islet transplanted patients: time for a change in outcome measures? Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2011; 2: 117– 125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, et al. Reduced awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM. A prospective study of hypoglycemic frequency and associated symptoms. Diabetes Care. 1995; 18: 517– 522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development: Sage Publications, Inc. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3: 77– 101. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neuman WL. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches: Allyn and Bacon. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schipper K, Abma T, Koops C, et al. Sweet and sour after renal transplantation: a qualitative study about the positive and negative consequences of renal transplantation. Br J Health Psychol. 2014; 19: 580– 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orr A, Willis S, Holmes M, et al. Living with a kidney transplant: a qualitative investigation of quality of life. J Health Psychol. 2007; 12: 653– 662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nilsson M, Persson LO, Forsberg A. Perceptions of experiences of graft rejection among organ transplant recipients striving to control the uncontrollable. J Clin Nurs. 2008; 17: 2408– 2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Christensen AJ, Turner CW, Smith TW, et al. Health locus of control and depression in end-stage renal disease. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991; 59: 419– 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallston KA. Conceptualization and Operationalization of Perceived Control. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rutter M, Amiel S, Birtles L, et al. Islet cell transplant: what you need to know. http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/Guide to diabetes/Treatments/islet-cell-transplant-what-you-need-to-know-0513.pdf. London: Diabetes UK; 2012. (accessed: 30 September 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee P, Fung A, LYF W, et al. Psychological Assessment of Recipients and Donors in Liver Transplantation. In: Fan S, Lee PWH, Wei WI, eds. Living Donor Liver Transplantation: : World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.; 2011: 43. [Google Scholar]