Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, immune-mediated disease that is increasingly recognized as one of the most common causes of dysphagia and foregut symptoms in adults and children. Topical corticosteroids, elimination diets, and esophageal dilations are effective options for both induction and maintenance therapy in EoE. Current pharmacologic options are being used off-label as no agent has yet been approved by regulatory authorities. Little is known about the natural history of EoE, however, raising controversy regarding the necessity of maintenance and therapy in asymptomatic or treatment-refractory patients. Furthermore, variability in treatment endpoints used in EoE clinical trials makes interpretation and comparability of EoE treatments challenging. Recent validation of a patient-related outcome (PRO) instruments, a histologic scoring tool, and an endoscopic grading system for EoE are significant advances toward establishing consistent treatment endpoints.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Esophageal stricture, Dysphagia, Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Esophageal dilation

Introduction

Over the past two decades, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has emerged as one of the most common causes of dysphagia in children and adults. Studies have identified a number of medical, dietary and endoscopic therapies that are highly effective at remedying the symptoms, signs and histopathology of EoE. This review will focus on overall management strategies in EoE, specifically discussing the definition of therapeutic response, selection of initial therapy, controversies regarding the rationale for maintenance therapy and considerations for refractory disease.

Definition of response to therapy

The overall goals of therapy of EoE include alleviation of presenting symptoms as well as prevention of disease progression, improvement in quality of life and reversal of existing complications. Understanding the natural history of EoE is of central importance to a discussion of therapeutic goals. If EoE were a self-limited condition, short-term therapy or clinical observation would be appropriate. On the other hand, a chronic or progressive course would favor early intervention and maintenance therapy. Unfortunately, little is known regarding the natural history of EoE, creating a challenge in patient management, particularly in those with minimal symptoms. In the longest follow-up study to date, Straumann et al. followed 30 adult patients for an average of seven years in the absence of medical or diet therapy [1]. During the study period, all patients maintained a stable nutritional state, but 97% of patients continued to experience dysphagia. Dysphagia increased in 23%, was stable in 37% and improved in 37% of patients. Esophageal eosinophilia persisted but demonstrated an overall decline in most patients. The one third of the cohort who received esophageal dilation likely affected the reported symptom outcomes but not the histologic outcomes. Subsequent retrospective studies have demonstrated progression of dysphagia in children with EoE as well as progressive esophageal stricture in adults with increased duration of untreated disease [2]. The prevalence of esophageal fibrostenosis increased from 47% in patients with a diagnostic delay of less than two years to 88% in those with delay of over 20 years.

Several chronic esophageal mucosal disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, tylosis, caustic injury and radiation esophagitis, have been associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer. To date, no cases of esophageal neoplasia related to EoE have been reported. Barrett's meta-plasia has been reported in patients with EoE [3], but it is unclear as to whether this is a causal relationship or just chance co-existence of two conditions.

Considerable variability exists in the selection and use of treatment endpoints currently used in EoE therapeutic trials. Given that esophageal mucosal eosinophilia is a necessary feature of EoE, most studies have focused on histology as a marker for response to therapy. While eosinophils are numerically abundant, readily identified on routine microscopy and possess degranulation proteins capable of inflicting esophageal injury, their exact role in the pathogenesis of EoE is incompletely understood. Quantification of staining for eosinophil products such as major basic protein, eosinophil degranulation protein and eosinophil peroxidase is being examined as a more sensitive measure of disease activity. Mast cells, lymphocytes and basophils are also evident in EoE and have increasingly recognized significance in EoE pathogenesis. A more intricate approach is examining the expression of both upregulated and downregulated genes in esophageal tissue as a biomarker of disease status.

With these caveats in mind, ongoing studies are continuing to recognize esophageal eosinophilia as the most appropriate biomarker of EoE activity. The specific threshold, however, for reduction in esophageal eosinophilia to define treatment efficacy is uncertain. Histologic response has been defined in numerous ways and both as relative percent reduction in eosinophilia and as absolute reduction in eosinophil density below a certain threshold (e.g. <15, <10, and <5 eosinophils per high power field). Some investigators have utilized mean eosinophil density derived from summation of multiple biopsy sites from varied esophageal locations rather than peak eosinophil density. Furthermore, histopathology is prone to sampling error because of variability in specimen processing (depth of tissue cuts, tissue orientation, microscope parameters), differences in the degree of esophageal eosinophilia amongst individual biopsies, and absence of evaluable subepithelial tissue, which is considered a histologic correlate of esophageal remodeling [4,5].

Assessing symptomatic response as an endpoint in EoE therapy also presents a challenge. Patients with EoE may change their eating behaviors purposely or subconsciously, modifying their diets to avoid foods that are difficult to swallow or increasing mastication time during meals. This adaptive behavior may not be reflected in routine clinical assessment or patient reported outcome instruments. Secondly, dysphagia and food impaction are sporadic events and may not be captured in therapeutic studies of short duration. Patient-related outcome (PRO) instruments including the EoE Activity Index (EEsAI) and Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) have recently been validated in adults. The EEsAI includes several factors that assess dysphagia, behavioral adaptations to dysphagia, and pain with swallowing [6]. Limitations of the PRO tool include doubts regarding sensitivity in milder forms of EoE and the shortcomings of questioning patients about a hypothetical test meal rather than having a trained observer physically watching a patient eat various foods [7].

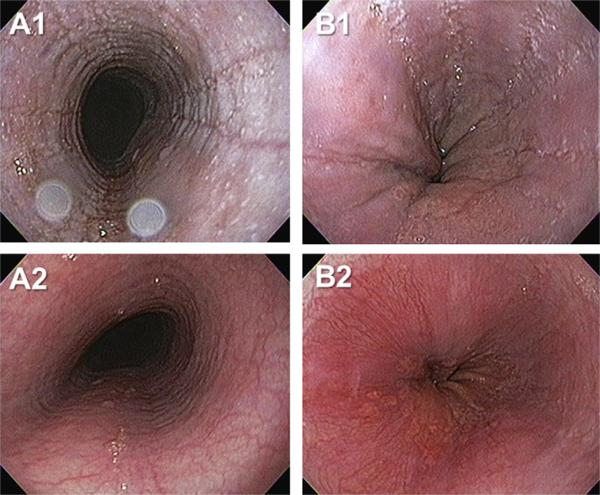

Endoscopic improvement is not currently utilized as a primary EoE treatment outcome but provides important information on disease activity and severity, including mucosal inflammatory and structural remodeling consequences of disease. Recent validation of the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS) in both US and European centers provides an endoscopic classification and grading system to assess the five major esophageal features of EoE: Edema, Rings, Exudates, Furrows and Strictures [8]. EREFS severity is a major determinant of physician global assessment of disease activity and is associated with clinical outcomes of food impaction risk [9]. Endoscopic outcomes provide an objective, “end organ,” gross assessment of EoE activity that corroborate ongoing investigation in optimal treatment endpoints (Fig. 1). In recent years, endoscopically determined mucosal healing has become an important therapeutic goal in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. EoE and Crohn's disease share similarities in that both are chronic, immune disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that result in both inflammation and fibrostenotic complications.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopically identified esophageal features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Images A1 and B1 depict edema, rings, exudates and furrows of the esophagus from two patients (A, B). Images A2 and B2 depict the corresponding images from the same patients following six weeks of therapy with swallowed, topical fluticasone. Interval improvement in edema, exudate and furrows is evident.

Fibrostenotic consequences of EoE can be visually estimated by endoscopy. The quantitative assessment at the whole organ level by radiologic imaging with barium esophagram is readily available but carries risk of radiation exposure and inability to control for intraluminal pressure to distend the esophageal lumen. Measurement of esophageal mural compliance utilizing a functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) is a novel and quantitative methodology to assess remodeling in EoE. The FLIP technology incorporates a multichannel electrical impedance catheter and manometric sensor that provide a detailed interrogation of the compliance and distensibility of the esophageal wall. A study using FLIP in EoE found that EoE patients with a history of food impactions exhibited significantly lower esophageal distensibility than those with dysphagia alone [10]. Decreased esophageal distensibility was found to be associated with an increased risk of food impaction and need for dilation during a follow-up period.

Overall, symptoms and esophageal histopathology are the primary endpoints in current clinical trials of EoE. The role of endoscopically-identified esophageal features is emerging as a clinically relevant parameter that complements and substantiates the primary endpoints of disease activity assessment. Future therapeutic endpoints may incorporate novel parameters of esophageal distensibility determined by impedance planimetry, biomarkers of eosinophil activity, and gene expression panels.

Initial or “induction” therapy

Topical corticosteroids versus dietary therapy

Topical, swallowed corticosteroids represent the most widely utilized medical treatment for both children and adults with EoE (see chapter 11). Numerous pediatric and adult placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated fairly uniform histologic improvement with swallowed corticosteroids compared to placebo, but with variable degrees of symptomatic improvement [11–15]. Identification of symptom improvement over placebo response has proven challenging in randomized controlled trials of steroids. The dissociation between histologic improvement and symptomatic response has been attributed to presence of treatment-refractory fibrostenosis, high placebo response rates, adaptive eating behaviors, and use of non-validated instruments for symptom assessment. A recently completed randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of oral budesonide suspension in adolescents and adults with EoE was the first trial in EoE to demonstrate concordant histologic and symptom improvement utilizing a validated patient reported outcome instrument [16].

The rapidity of response combined with safety, based on their long-term use in asthma and allergic rhinitis position topical steroids as an attractive therapy. Many patients, however, voice reluctance to take medications on a chronic basis and express concerns about uncertain side effects of long-term steroid administration. Presently, topical steroids for EoE are used off-label, as no medical therapies have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Adverse side effects of oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis have been reported in 15–26% of patients treated with swallowed fluticasone, but are seldom clinically important. Another limitation to the use of topical steroids has been the high reported rates of symptom and histologic recurrence following drug cessation. The long-term effectiveness and safety of maintenance use of topical steroids for EoE are currently being investigated.

In the context of these concerns and uncertainties regarding topical steroids in the therapy of EoE, diet therapy is an attractive option for many patients (see Chapter ten). The goal of dietary therapy is identification and elimination of food antigens to consequently remove the trigger for allergic sensitization. Diet therapy offers patients a non-pharmacologic alternative to controlling their disease. In a broader context, studies across disciplines have demonstrated the widespread patient use of alternative medicine to many medical conditions, in spite of available conventional therapies. Many patients find the concept of remedying their disease by eliminating a dietary trigger more appealing than taking a drug to counteract the downstream inflammatory response. Furthermore, when discussing the diet approach, it is important to emphasize that the strict dietary removal of multiple foods is for a limited period of time. The long-term goal is the identification and long-term elimination of one or a few dietary factors. In addition, the notion by patients that they will “never” be able to eat an identified trigger food is incorrect. In contrast to food-related anaphylaxis, occasional dietary indiscretion is likely not a major concern. Prolonged deviation from the elimination diet can be managed by intermittent use of short courses of topical steroids. Moreover, as progress is made in the understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE, newer therapeutic options will almost certainly supplant the current management approach.

The three most commonly utilized diet strategies are the elemental diet, the empiric six-food elimination diet (SFED), and the limited diet driven by allergy testing and/or patient history. While highly effective in both pediatric [17–19] and adult studies [20], the elemental diet is limited by patient tolerability. An alternative approach is the SFED protocol, in which the six food groups most commonly known to trigger EoE – cow milk, soy, eggs, wheat, nuts, and fish/shellfish – are excluded, then systematically re-introduced to identify a specific food trigger. This approach has proven effective in inducing histologic and symptomatic improvement in both pediatric and adult patients studied [21–23]. The allergy testing directed diet approach, although effective in the children [24], has only moderate success in adults [25,26]. A retrospective pediatric study reported the highest rates of histologic remission in the elemental diet cohort (96% of patients), compared to the SFED cohort (81%) and the limited diet cohort (63%) [27].

As there are no head-to-head prospective controlled trials comparing topical steroids with elimination diets, the choice of treatment is currently individualized (Table 1, Fig. 2). The dietary approach requires a motivated patient and physician. Major lifestyle modification is needed. It is important to appreciate that an imposition is placed not only on the patient but also the patient's family who may have to modify their own eating habits to facilitate meal preparation and avoid cross contamination. Available resources are an important consideration in the choice of dietary therapy. Formal guidance and supervision by a dietician or allergist regarding food allergens, dietary recommendations and avoidance of nutrient deficiencies is of paramount importance for success. Internet resources focused on food allergy and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are valuable resources.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of current primary therapies of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults.

| Therapy | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

|

Swallowed steroids Fluticasone 440 –880 mcg BID Budesonide 1 –2 mg QD to BID |

• Consistent efficacy for improving histopathology in multiple randomized, controlled trials • Most extensively studied treatment modality • Topical application and first pass hepatic metabolism minimize systemic risks |

• Oral and/or esophageal candidiasis (15–30%) • Currently used formulations not optimized for esophageal delivery • No long-term safety data available • Disease recurrence following cessation |

|

Dietary elimination Elemental diet Empiric six-food elimination diet Allergy testing directed food elimination |

• Consistent improvement in histopathology in pediatric and adult trials (uncontrolled data) • Minimal side effects • Patient acceptance for non-pharmacologic approach |

• Risk for inadequate nutritional intake • Difficultly avoiding food contamination • Impact of food avoidance on quality of life • Cost and inconvenience of repeated endoscopies during food reintroduction to identify specific trigger |

| Esophageal dilation | • Immediate symptomatic relief • Long-term duration of response following adequate dilation (>1 year) |

• Does not address mucosal inflammation • Post-procedural chest pain common (75%) • Esophageal perforation although risk is low (<1%) • Bleeding risk |

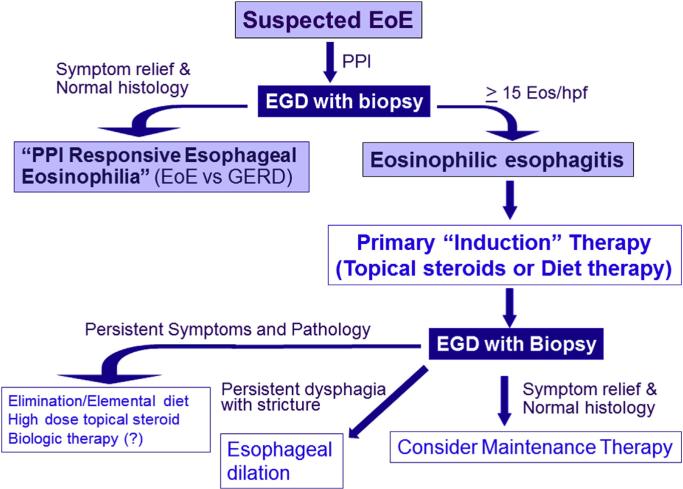

Fig. 2.

Suggested management algorithm for eosinophilic esophagitis. Patients presenting with esophageal symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia are suspected of having eosinophilic esophagitis. A treatment trial of proton pump inhibition is followed by an upper endoscopy with proximal and distal esophageal biopsies. Patients demonstrating histologic remission on proton pump inhibition are termed “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” to acknowledge the controversies in distinguishing GERD from eosinophilic esophagitis. For patients with persistent symptoms as well as endoscopic and histologic evidence of eosinophilic esophagitis, primary, “induction” therapy with either topical steroids or dietary elimination is initiated. A follow up endoscopy with biopsy is used to assess resolution of the endoscopic and pathologic alterations. Patients who do not respond to primary therapy are then candidates for alternative therapies including elemental diets, high dose topical steroids and novel therapeutics. Esophageal dilation is an effective method to address fibrostenotic consequences of eosinophilic esophagitis.

Esophageal dilation

Whereas swallowed corticosteroids and diet modification therapy presumably target the inflammation associated with the pathogenesis of EoE, esophageal dilation targets the fibrostenotic complications of the disease (see Chapter 12). Several case series suggest esophageal dilation is well-tolerated by patients and provides long-lasting symptomatic relief despite having no effect on mucosal eosinophilia [28–31]. Esophageal dilation offers an important adjunct to topical corticosteroids and/or dietary therapy and may be considered in patients unresponsive to initial medical or diet therapy.

Combination therapy

There are few studies prospectively exploring combination therapy in EoE. Targeting mucosal inflammation with diet or steroids and addressing fibrostenosis with esophageal dilation is supported by current guidelines. One blinded randomized controlled trial comparing swallowed corticosteroids alone to swallowed corticosteroids together with esophageal dilation in 31 adults with EoE showed no difference in dysphagia outcomes [32]. The study excluded patients with high grade esophageal stenosis and did not utilize validated symptom assessment, thus limiting its generalizability. Several studies examining topical steroids have allowed for concomitant use of PPI therapy, though a potential synergistic effect of the combined use of steroids and PPI was not specifically reported. Combining diet therapy with steroids is not recommended as steroids interfere with the detection of eosinophilia that serves as the indicator of disease activity during food reintroduction.

Patients refractory to therapy

Although the majority of patients have histologic and symptomatic response to either elimination diet or topical steroids, a subset of patients are refractory to therapy. These patients may demonstrate persistent esophageal inflammation, persistent symptoms, or both. In addition, a patient may demonstrate both symptomatic and histologic response but have persistent esophageal luminal stenosis. This patients may be a candidate for esophageal dilation. Age, height, weight, atopic status or baseline eosinophil density did not predict response. Esophageal transcriptome analysis did identify a subset of genes with predictive value for fluticasone response. In an adult retrospective study of topical steroid therapy, baseline esophageal dilation predicted steroid nonresponse and abdominal pain predicted steroid response.

Patients not responding to topical steroids should be questioned as to adherence, dosing, and appropriate method of administration. Adherence to medications can be challenging for adolescent and young adult patients, most of whom are unaccustomed to the use of medications on a long-term basis. Patients may be inadvertently inhaling instead of swallowing aerosolized steroid. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated greater effectiveness in reducing esophageal eosinophilia of a liquid suspension of budesonide compared to nebulized budesonide [33], though this result cannot be extrapolated to topical steroids delivered by means of a metered dose inhaler. Dose escalation of topical steroids is a consideration though prospective studies comparing various dosing regimens are lacking. Higher response rates have been reported in adult studies using fluticasone 880 mcg twice daily compared with those using 440 mcg twice daily though these studies were conducted separately and thus are fraught with confounding variables. Systemic steroids are often considered superior to topical steroids. A randomized trial, however, found similar efficacy in terms of the primary endpoint of a histopathology score for topical fluticasone compared with oral prednisone in a pediatric cohort [34]. Diet therapy is an option for patients unresponsive to topical steroids although there are only anecdotal reports regarding the effectiveness of this sequential approach. Other medical therapies including montelukast, cromolyn sodium or antihistamines have shown limited benefits in a few small uncontrolled studies and are considered second line agents. The effectiveness of therapies combining steroids, diet, montelukast and antihistamines have not been reported for refractory patients. Furthermore, the optimal duration of medical or diet therapy has not been established.

To address the needs of EoE patients who are either refractory to traditional therapy or who are chronically dependent on corticosteroids, alternative therapies are being investigated. Several studies of targeted immunologic therapy with IL-5 antibodies (mepolizumab, reslizumab) showed reduction in esophageal eosinophilia but no significant symptomatic improvement [35–37]. Moderate histologic improvement was demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial of anti-IL-13 therapy [38] as well as in a randomized trial of the CRTH2 antagonist OC000459 [39]. Anti-IgE therapy, however, did not improve histologic or endoscopic disease activity in a study evaluating the efficacy of Omalizumab [40].

One study examining azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in EoE demonstrated both histologic and symptomatic improvement, though the disease flared with withdrawal of medication [41]. A case series of high-dose montelukast showed symptomatic improvement in the majority of the eight patients examined [42], but a subsequent study did not show substantial histologic or clinical improvement with montelukast used as maintenance therapy after induction with topical corticosteroids [43].

Maintenance therapy

Maintenance therapy is an important consideration since the majority of EoE patients develop recurrent symptoms and recurrent esophageal eosinophilia upon cessation of medical or diet therapy. For patients with mild and intermittent dysphagia without significant strictures or food impaction, intermittent on-demand therapy may be appropriate assuming that the patient is reliable and has appropriate clinical follow-up. For patients with severe dysphagia, repeated food impaction, and high-grade esophageal strictures at presentation and who respond to initial therapy, maintenance therapy seems reasonable. A pediatric study of fluticasone found that over 90% of patients maintained histologic responsiveness with a 50% reduction in induction dose [44]. Benefits of maintenance therapy is supported by a retrospective, multivariate analysis of EoE adults with five years of follow-up that found that continuation of swallowed topical corticosteroid therapy was associated with a reduced risk of food impaction (OR 0.411, 95% CI 0.203–0.835) [45]. However, an adult, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 50-week trial that used a maintenance budesonide dose that was 25% of the dose used to achieve initial remission found that only 50% of patients maintained histologic response at 50 weeks [46].

Several studies examining the natural history of EoE suggest that although EoE is a recurrent, chronic disease, it appears benign and not associated with risk of malignancy [47–50]. Consequently, periodic esophageal dilation has been proposed as an alternative well-tolerated, long-term treatment approach that results in prolonged relief in dysphagia [51].

Treatment of asymptomatic patients

Based on current consensus guidelines, patients with significant esophageal eosinophilia on biopsy but without symptoms do not meet diagnostic criteria for EoE [52]. However, patients may have substantial esophageal luminal stenosis but may not report dysphagia due to careful mastication, prolonged meal times, and food avoidance. Patients may have relevant esophageal inflammation for years prior to the onset of dysphagia for which they seek medical attention. The same situation may be encountered in patients initially diagnosed with EoE who achieve symptomatic but not histologic remission following medical or dietary therapy. Presently, there is limited evidence to support additional treatment of such individuals. A more proactive approach might be considered in asymptomatic patients with eosinophilia and higher degrees of esophageal stenosis, as well as in patients with eosinophilia who have a history of significant disease complications such as food impaction or esophageal stricture. Given the uncertainties regarding the natural history of EoE, clinical follow-up for patients with esophageal eosinophilia even in the absence of symptoms is reasonable. Growing evidence supports the concept that untreated disease leads to higher degrees of esophageal stricture formation over time [53], further supported by the observation that patients with an inflammatory EoE phenotype tend to be younger whereas patients with a fibrostenotic phenotype tend to be older [54].

Conclusions

Heightened uncertainty as well as innovation are expected in the development of effective therapeutic strategies for a relatively new disease. As the mechanisms underlying the disease are elucidated, novel EoE therapies are rapidly evolving. Concurrently, the appropriate endpoints for therapeutic response in EoE are being defined and refined. Patient reported outcome instruments are completing validation while novel physiologic and genetic biomarkers are being proposed. Current, first-line treatments include topical corticosteroids, elimination diets, and esophageal dilation. Maintenance therapy is recommended to prevent disease recurrence and progression but on-demand approaches may be reasonable and practical in specific cases.

Practice points.

- Topical steroids and elimination diets are effective, first-line treatments for eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Natural history studies suggest that untreated eosinophilic esophagitis is a disease with progressive esophageal remodeling and fibrostenosis.

- Measures to assess therapeutic response in eosinophilic esophagitis include validated patient reported outcomes for symptoms and quality of life, histologic scores for eosinophilic inflammation, a validated grading system for endoscopic features, and biomarker panels depicting genetic expression in the esophageal mucosa.

- Esophageal dilation is an effective means of managing strictures that are not amenable to medical or diet therapies for eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Systemically delivered biologic therapies that target cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis are being investigated as potential, disease modifying agents.

Research agenda.

- Further studies are needed to more fully understand the natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis to better inform therapeutic decisions.

- Prospective studies evaluating both long-term maintenance treatment and combination therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis are awaited.

- Standardization of therapeutic endpoints in future studies will allow for better cross-comparability among clinical trials in eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Randomized, controlled trials of diet therapies will provide data to optimize the most appropriate use of this non-pharmacologic approach to the management of eosinophilic esophagitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge research funding support from the NIH for the Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal disease Researchers (NIH U54AI117804), which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network, an initiative of the Office of Rare Disease Research and is funded through a collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK and NCATS) and an American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Research Award.

Abbreviations

- CRTH2

chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule on Th2 cells

- EOE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- DSQ

dysphagia symptom questionnaire

- EEsAI

eosinophilic esophagitis activity index

- FLIP

functional luminal imaging probe

- IL-5

interleukin-5

- IL-13

interleukin-13

- PRO

patient-related outcome

- SFED

six-food elimination diet

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr. Hirano has served as a consultant for Receptos, Regeneron, Shire and Roche pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sodikoff has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, Bucher KA, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003 Dec;125(6):1660–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, Kuchen T, Portmann S, Simon HU, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Schoepfer AM, Straumann A, Panczak R, Coslovsky M, Kuehni CE, Maurer E, et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec;147(6):1255–1266.e21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almansa C, Wolfsen H, Devault K, Achem SR. Coexistence of Barrett's esophagus and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:S144. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Sep;64(3):313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano I, Aceves SS. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014 Jun;43(2):297–316. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter JE. New questionnaire for eosinophilic esophagitis: will it measure what we want? Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec;147(6):1212–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013 Apr;62(4):489–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoepfer AM, Panczak R, Zwahlen M, Kuehni CE, Coslovsky M, Maurer E, et al. International EEsAI Study Group. How do gastroenterologists assess overall activity of eosinophilic esophagitis in adult patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Mar;110(3):402–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicodème F, Hirano I, Chen J, Robinson K, Lin Z, Xiao Y, et al. Esophageal distensibility as a measure of disease severity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Sep;11(9):1101–1107.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta SK, Vitanza JM, Collins MH. Efficacy and safety of oral budesonide suspension in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;13(1):66–76.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, Enders F, Katzka DA, Kephardt GM, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jul;10(7):742–749.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Felder S, Kummer M, Engel H, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, Hirano I. Oral budesonide suspension significantly improves dysphagia and esophageal eosinophilia: results from a multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in adolescents and adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):S–157. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Verma R, Mascarenhas M, Semeao E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995 Nov;109(5):1503–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet in an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:777–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Franciosi JP, et al. Utility of an elemental diet in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Suppl. 1):AB 1080. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Hess T, Nelson SP, Emerick KM, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Sep;4(9):1097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jun;142(7):1451–1459.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001. quiz e14–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á , González-Cervera J, Yagüe-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Mar;131(3):797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spergel JM, Beausoleil JL, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras CA. The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:363–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molina-Infante J, Martin-Noguerol E, Alvarado-Arenas M, Porcel-Carreño SL, Jimenez-Timon S, Hernandez-Arbeiza FJ. Selective elimination diet based on skin testing has suboptimal efficacy for adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1200–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon D, Straumann A, Wenk A, Spichtin H, Simon HU, Braathen LR. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults—no clinical relevance of wheat or rye sensitization. Allergy. 2006;61:1480–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Franciosi JP, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1570–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohm M, Richter JE, Kelsen S, Thomas R. Esophageal dilation: simple and effective treatment for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal rings and narrowing. Dis Esophagus. 2010 Jul;23(5):377–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, Conus S, Simon HU, Straumann A, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 May;105(5):1062–70. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoepfer AM, Gschossmann J, Scheurer U, Seibold F, Straumann A. Esophageal strictures in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: dilation is an effective and safe alternative after failure of topical corticosteroids. Endoscopy. 2008 Feb;40(2):161–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robles-Medranda C, Villard F, le Gall C, Lukashok H, Rivet C, Bouvier R, et al. Severe dysphagia in children with eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal stricture: an indication for balloon dilation? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 May;50(5):516–20. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b66dbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kavitt RT, Ates F, Slaughter JC, Higginbotham T, Vaezi MF. Dilate or medicate? A randomized, blinded, controlled trial comparing esophageal dilation to no dilation among adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2012 May;146(5):S16–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, Woodward K, Whitlow AB, Hores JM, et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Aug;143(2):321–324.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Feb;6(2):165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010 Jan;59(1):21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G, 3rd, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Feb;129(2):456–463. 463, e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Assa'ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, Thomson M, Heath AT, Smith DA, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011 Nov;141(5):1593–604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Feb;135(2):500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straumann A, Hoesli S, Bussmann Ch, Stuck M, Perkins M, Collins LP, et al. Anti-eosinophil activity and clinical efficacy of the CRTH2 antagonist OC000459 in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2013 Mar;68(3):375–85. doi: 10.1111/all.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rocha R, Vitor AB, Trindade E, Lima R, Tavares M, Lopes J, et al. Omalizumab in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis and food allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(11):1471–4. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Oct;19(10):865–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32825a6ab4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attwood SE, Lewis CJ, Bronder CS, Morris CD, Armstrong GR, Whittam J. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: a novel treatment using Montelukast. Gut. 2003 Feb;52(2):181–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucendo AJ, De Rezende LC, Jiménez-Contreras S, Yagüe-Compadre JL, González-Cervera J, Mota-Huertas T, et al. Montelukast was inefficient in maintaining steroid-induced remission in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Dec;56(12):3551–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1775-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ, Furuta GT, Spergel J, King E, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014 Aug;147(2):324–333.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, Romero Y, Bussmann C, Vavricka S, et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long-lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2014 Sep;69(9):1248–54. doi: 10.1111/all.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *46.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 May;9(5):400–409.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Assa'ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Akers RM, Jameson SC, Kirby CL, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Mar;119(3):731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Franciosi J, Shuker M, Verma R, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):30–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, Butz BK, Greenberg AB, Collins MH, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, Ruchelli E. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26:380–5. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipka S, Keshishian J, Boyce HW, Estores D, Richter JE. The natural history of steroid-naïve eosinophilic esophagitis in adults treated with endoscopic dilation and proton pump inhibitor therapy over a mean duration of nearly 14 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014 Oct;80(4):592–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *52.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA. American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679–92. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. quiz 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menard-Katcher P, Marks KL, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Yang YX, Falk GW. The natural history of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the transition from childhood to adulthood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jan;37(1):114–21. doi: 10.1111/apt.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014 Apr;79(4):577–585.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]