Abstract

In reaching to grasp an object, proximal muscles that act on the shoulder and elbow classically have been viewed as transporting the hand to the intended location, while distal muscles that act on the fingers simultaneously shape the hand to grasp the object. Prior studies of electromyographic (EMG) activity in upper extremity muscles therefore have focused, by and large, either on proximal muscle activity during reaching to different locations or on distal muscle activity as the subject grasps various objects. Here, we examined the EMG activity of muscles from the shoulder to the hand, as monkeys reached and grasped in a task that dissociated location and object. We quantified the extent to which variation in the EMG activity of each muscle depended on location, on object, and on their interaction—all as a function of time. Although EMG variation depended on both location and object beginning early in the movement, an early phase of substantial location effects in muscles from proximal to distal was followed by a later phase in which object effects predominated throughout the extremity. Interaction effects remained relatively small. Our findings indicate that neural control of reach-to-grasp may occur largely in two sequential phases: the first, serving to project the entire upper extremity toward the intended location, and the second, acting predominantly to shape the entire extremity for grasping the object.

Keywords: arm, hand, manipulation, electromyography, EMG

the processes of reaching and of grasping classically have been viewed as proceeding in parallel (Jeannerod 1984, 1986). Once one has decided to take a sip of coffee, for example, the nervous system knows both that the arm will need to reach toward the cup and that the hand will need to grasp the cup. At the level of action planning, the nervous system thus may control reaching and grasping concurrently; however, at the final output level of kinematics, we recently found that joint angles varied largely in two sequential phases, rather than as two parallel processes (Rouse and Schieber 2015b). In an early phase, variation in joint angles from the shoulder to the hand depended largely on the location to which the arm was reaching; in a later phase, joint angle variation—again, from the shoulder to the hand—depended predominantly on the object about to be grasped. Do these two phases simply reflect the kinematics necessary to grasp various objects at various locations, or is reach-to-grasp actually driven in two sequential phases?

Electromyographic (EMG) activity reflects the output of motoneuron populations, the final common pathway through which the cortex, brain stem, spinal cord, and other neural centers control movement. Because reaching and grasping have been viewed as separate, parallel processes, however, most studies of muscle activation have focused either on proximal muscles during reaches to various locations or on distal muscles during grasps of various objects. For example, the proximal muscle activity that drives the motion of the arm for reaching typically has been studied by having human subjects reach to various locations without grasping different objects. During such movements, proximal EMG activity can be broadly dissociated into two components: tonic and phasic (Flanders 1991; Flanders and Herrmann 1992). Whereas the tonic component supports the limb against gravity, the phasic activation of proximal muscles both changes in amplitude and shifts in time as a function of reach direction and speed (Buneo et al. 1994; D'Avella et al. 2008; Flanders et al. 1996). When subjects reached to grasp three different objects at three different locations, however, the EMG activity of proximal muscles showed distinct patterns, based not only on location but on object as well (Martelloni et al. 2009).

Conversely, the distal muscle activity that drives the hand for grasping typically has been examined independent of reaching to different locations (Maier and Hepp-Reymond 1995; Valero-Cuevas 2000). The problems of relating the activity of various muscles to the mechanics of the grasping hand are complex (Schaffelhofer et al. 2015; Towles et al. 2013; Valero-Cuevas 2005; Valero-Cuevas et al. 2003). Nevertheless, when 6–8 objects, which differ in size and shape, are all presented at the same location, the object that is being grasped can be decoded from the EMG activity of 8–12 forearm and intrinsic hand muscles (Brochier et al. 2004; Fligge et al. 2013). The decoding accuracy increases progressively during the movement, approaching 100% correct object classification midway through the reach, indicating that patterns of activation across the set of distal muscles become more object specific as the movement evolves.

In one study that examined the simultaneous activity of proximal and distal muscles in a task that combined reaching to different locations and grasping different objects, the EMG activity of shoulder and elbow muscles peaked, on average, 125 ms after movement onset, whereas the activity of extrinsic digit muscles peaked later, at 221 ms (Stark et al. 2007). This observation might reflect sequential activity, first in proximal and then in distal muscles. To test the hypothesis that reaching and grasping are driven, in large part, sequentially rather than completely in parallel, we studied the EMG activity of muscles from the shoulder to the hand, as monkeys performed a reach-grasp-manipulate task that dissociated location and object.

METHODS

Subjects and Behavioral Task

Three Rhesus monkeys—L, X, and Y (all males, 9–11 kg)—were subjects in the present study. All procedures for the care and use of these nonhuman primates followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester (Rochester, New York).

Each monkey performed a behavioral task described in detail previously (Rouse and Schieber 2015b). The monkey reached to, grasped, and manipulated four objects: a coaxial cylinder, perpendicular cylinder, button, and sphere, arranged at 45° intervals on a circle—each of these peripheral objects positioned at a 13-cm radius from a fifth, center object, another coaxial cylinder. The entire apparatus was rotated about the center in blocks of trials, such that different objects were located at up to eight locations, spanning a range from 0° (to the monkey's right on the horizontal meridian) to 157.5° (to the left, 22.5° above the horizontal meridian) in steps of 22.5°. Although the 8 locations and 4 objects provided 32 possible location–object combinations, we used only 24 combinations, because of 3 factors: visual occlusion of some locations by the primate chair, biomechanical limitations of the arm, and mechanical constraints of the apparatus, as described in detail previously (Rouse and Schieber 2015b).

The monkey initiated each trial by grasping and pulling on the central object, positioned 32 cm in front of the shoulder. After a variable initial hold period (1,500–2,000 ms for monkey L; 1,000-1,500 ms for monkeys X and Y), blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) were illuminated around the base of the horizontal rod, supporting one of the four peripheral objects, instructing the monkey to reach to, grasp, and manipulate that object. Onset of movement (M) was identified from motion-capture data as the monkey released the center object (Rouse and Schieber 2015b). Thirty-six markers placed on the skin from the upper arm to the fingers, all were tracked simultaneously with an 18 camera system (Vicon, Denver, CO). The onset of movement was defined as the time at which average marker speed exceeded 5 SD of the baseline sampled during the initial hold period, while the monkey statically held the central object. Peripheral object contact (C) was detected with semiconductor strain gauges mounted on the horizontal supporting rods. Upon grasping, the monkey pulled the perpendicular cylinder, pulled the coaxial cylinder, pushed the button, or rotated the sphere, closing a separate microswitch by manipulating each object appropriately. Green LEDs, at the base of the horizontal rod supporting the manipulated object, were illuminated as long as the microswitch was closed. The monkey was then required to hold the switch closed for 1,000 ms before receiving a water reward. Trials of different objects were presented in a pseudorandom block design.

Errors occurred if the monkey failed to release the center object within 1,000 ms of the blue LED instruction onset, failed to contact the instructed peripheral object within 1,000 ms of releasing the center object, contacted the wrong peripheral object, or failed to maintain the static, final hold position for 1,000 ms. Following any error, the trial was aborted immediately, and the same object was presented on subsequent trials until the trial was performed successfully. Because the monkey thus knew which type of trial would follow an error trial, trials preceded by an error trial were excluded from analysis, as were all error trials. All aspects of the behavioral task were controlled by custom software running in TEMPO (Reflective Computing, Olympia, WA), which also sent behavioral event markers into the collected data stream.

Data Collection

EMG electrodes were made from 32 gauge, Teflon-coated, multistranded, stainless-steel wire. These wires were implanted as bipolar pairs in 16 arm and hand muscles of the right upper extremity, using an approach adapted from that of Cheney and colleagues (Park et al. 2000) and described in detail elsewhere (Davidson et al. 2007). The tips of each bipolar pair of recording electrodes were separated by 5–10 mm along the long axis of the muscle. Wires were tunneled subcutaneously up the arm and posterior to the shoulder to exit through the skin of the back in four separate bundles, a few centimeters to the right of the midline. Each bundle ended in a separate connector that was sewn onto the interior aspect of a jacket (Alice King Chatham, Hawthorne, CA), which the monkey wore thereafter. During recording sessions, the back of the jacket was unzipped to provide access to the four connectors. The recorded muscles and abbreviations used are given in Table 1, where the muscles have been grouped according to proximodistal location in the upper extremity. For monkey Y, two bipolar electrode pairs were placed in the radial and ulnar aspects of extensor digitorum communis (EDC; EDC23 and EDC45, respectively), whereas none was placed in extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB).

Table 1.

Muscles implanted for EMG recordings

| Group | Muscle | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal arm (shoulder and elbow) | Deltoid–anterior | DLTa |

| Deltoid–posterior | DLTp | |

| Pectoralis major | PECmaj | |

| Biceps–short head | BCPs | |

| Triceps–lateral head | TCPlat | |

| Wrist | Flexor carpi radialis | FCR |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris | FCU | |

| Extensor carpi radialis brevis | ECRB | |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris | ECU | |

| Extrinsic hand | Flexor digitorum profundus–radial | FDPr |

| Flexor digitorum profundus–ulnar | FDPu | |

| Abductor pollicis longus | APL | |

| Extensor digitorum communis | EDC (EDC23 and EDC45*) | |

| Intrinsic hand | Thenar muscle group | Thenar |

| First dorsal interosseus | FDI | |

| Hypothenar muscle group | Hypoth |

For monkey Y, 2 separate, bipolar electrode pairs were implanted in the radial and ulnar aspect of EDC (EDC23 and EDC45, respectively), whereas none was placed in ECRB.

Bipolar signals from these electrodes were differentially amplified with headstages (HST/8o50, 20× gain, 30-30,000 Hz bandpass; Plexon, Dallas, TX) and passed through a hardware preamplifier (PRA2/EMG-16-002, 50× gain, 300-3,000 Hz bandpass; Plexon). EMG signals then were sampled at 1,000 Hz, amplified to a final gain of 1,000–20,000× (PXI-6071E; National Instruments, Austin, TX), and stored to disc by Plexon's SortClient. Offline, the EMG signals were full-wave rectified and then low-pass filtered bidirectionally (0-phase lag), using a second-order digital Butterworth filter with a cutoff of 20 Hz before further analysis.

Temporal Normalization of EMG Data

To permit analysis of EMG activity across trials of different duration, the data in each trial between two time points—movement onset (M) and peripheral object contact (C)—were normalized with linear interpolation and resampled to the median movement time across all trials in a given session. Data for 250 ms before movement onset were maintained at the original time scale, whereas data for 250 ms after peripheral object contact were normalized with the same time scaling used between movement onset and object contact in each trial.

Data Analysis

Analysis of variance.

As applied previously to kinematic data from the same experiment (Rouse and Schieber 2015b), time-resolved ANOVA was performed to examine the manner in which variation in EMG amplitude depended on location (8 categories), on object (4 categories), and on their interaction (location × object), all as a function of time. The normalized effect size, ηi2, of each factor was calculated at each time point, t, as

| (1) |

where i = Loc, Obj, or Loc × Obj, and SS represents the sum-of-squares variance related to each factor. We chose to normalize effect size by using the maximum error SS (SSError) variance observed across all time points, so as to reduce the fluctuations in effect sizes that resulted from temporal fluctuations in unexplained variance. The use of the maximum SSError in this way tended to reduce the estimated location, object, and interaction effect sizes but permitted better comparison of different effect sizes across time. Significance was evaluated with an ANOVA F-test, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons (i.e., using a significance threshold of P < 0.05, divided by the number of time points tested, that number being the median movement time for the session in milliseconds plus 250 before movement and 250 after peripheral object contact).

In addition to quantifying effect sizes, we calculated relative ratios of summed squared variance for the following: 1) location vs. object (Qm) and 2) interaction (Location × Object) vs. the two main factors (Qx). These ratios ignore the summed squared variance of the error term and simply compare the extent to which variance depended on the given factors. For

| (2) |

a value of zero indicates an object effect with no location effect, whereas a value of one corresponds to a location effect with no object effect. For

| (3) |

a value of zero indicates that no variance was attributable to the interaction term (i.e., independent main effects), whereas a value of one indicates that all variance was attributable to the interaction effect and none to either main factor.

Linear discriminant analysis.

An effect that accounts for a relatively small fraction of the overall variance in ANOVA does not necessarily indicate that different categories of that factor cannot be discriminated. We therefore extended our analysis using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to determine how accurately location or object could be predicted as a function of time, based on the rectified EMG signals. LDA was performed separately using EMG signals from each of the four proximodistal muscle groups defined in Table 1. LDA classification of location was performed separately for each object, and conversely, LDA classification of object was performed separately for each location. Each LDA was cross-validated 10-fold. Ninety-five percent Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals were generated with an exact binomial fit (Clopper and Pearson 1934; Newcombe 1998).

RESULTS

We analyzed upper extremity EMG activity recorded in multiple sessions from each of three monkeys, as detailed in Table 2. One of these sessions from each monkey, marked in Table 2 with asterisks, was used in our previous study of joint angle kinematics (Rouse and Schieber 2015b). The present results focus on the interval in each of these trials from movement onset until contact with a peripheral object, which differed among the three monkeys (P < 10−3, Kruskal-Wallis test). The median duration of the reach-to-grasp epoch ranged from 231 to 269 ms for monkey L, 211 to 285 ms for monkey X, and 283 to 334 ms for monkey Y. Although 16 bipolar electrode pairs were implanted in each monkey, satisfactory recordings were not obtained from every implanted muscle. EMG recordings with insufficient signal or excessive noise were excluded from analysis. Consequently, we analyzed EMG activity in 13 muscles from monkey L, 15 from monkey X, and 11 from monkey Y.

Table 2.

EMG recording sessions

| Monkey | Session | Number of Trials | Median Movement Time, ms |

|---|---|---|---|

| L | 20120924 | 657 | 238 |

| 20120926 | 617 | 255 | |

| 20120927 | 622 | 232 | |

| 20120928* | 676 | 253 | |

| 20121004 | 652 | 257 | |

| 20121017 | 675 | 269 | |

| 20121022 | 640 | 231 | |

| 20121024 | 769 | 246 | |

| X | 20121206 | 654 | 213 |

| 20121207 | 703 | 211 | |

| 20121210 | 730 | 242 | |

| 20121212 | 698 | 224 | |

| 20121213 | 704 | 285 | |

| 20121214 | 641 | 228 | |

| 20121218 | 723 | 257 | |

| 20121219* | 750 | 233 | |

| Y | 20130510 | 480 | 309 |

| 20130515 | 591 | 299 | |

| 20130516* | 628 | 334 | |

| 20130522 | 652 | 283 |

The session from each monkey analyzed in our study (Rouse and Schieber 2015b) of joint angle kinematics during the same behavioral task. The median movement times for these sessions (boldface) were used here to normalize the time base across all sessions for each monkey in Fig. 6 and provided the exemplar results shown in Figs. 7–9.

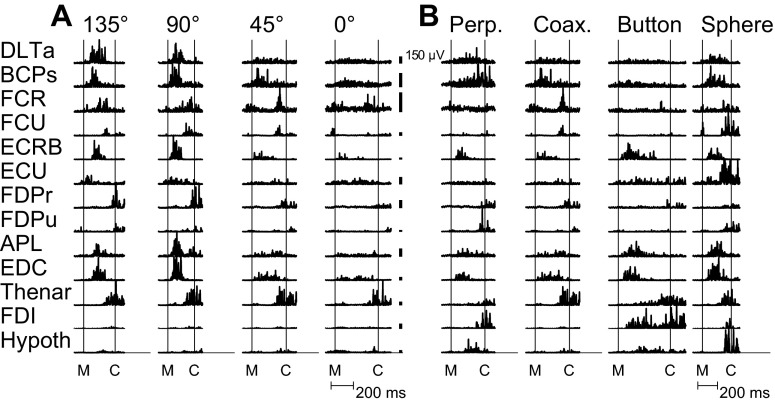

Time Course of EMG Activity

Representative single trials of rectified EMG activity from the 13 muscles recorded simultaneously from monkey L in one session are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1A shows single trials of EMG activity during movements to the same object—the coaxial cylinder—when placed at four different locations. EMG activity varied depending on location, not only in proximal muscles, such as anterior deltoid (DLTa) and biceps (BCPs), but also in more distal muscles, such as abductor pollicis longus (APL) and EDC. Figure 1B shows EMG activity during movements to the four different objects when placed at the same location (45°). Some general similarities were evident across the four objects. For example, digit extensors, such as APL and EDC, tended to become active earlier than flexors, such as flexor digitorum profundus–radial (FDPr) and flexor digitorum profundus–ulnar (FDPu), as the monkey first opened and then closed the hand. Nevertheless, for each muscle, EMG activity differed substantially depending on the object. Object-dependent variation was apparent, not only in distal muscles but in proximal muscles as well.

Fig. 1.

Examples of rectified EMG activity recorded from 13 muscles during individual trials. A: EMG activity during reach-to-grasp of the coaxial cylinder at 4 different locations. EMG activity in both proximal and distal muscles varied as a function of location. B: EMG activity from the same muscles during reach-to-grasp of the 4 different objects when each was located at 45°. Activity in proximal as well as distal muscles differed across the 4 objects. Activity also appeared to occur largely in 2 sequential temporal phases, with an early phase shortly after movement onset (M) and a later phase before contact (C) with the object. Early- and late-phase activity occurred in both proximal and distal muscles. The individual trials shown here were selected because they best matched the mean activity for a given location–object combination across the entire recording session. Note that the same trial for the coaxial cylinder at 45° appears in both A and B. Vertical calibration bars represent 150 μV for the EMG of each muscle. No time normalization has been applied. Data from session L20120928. FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FDI, first dorsal interosseus; Thenar, thenar muscle group; Hypoth, hypothenar muscle group; Perp., perpendicular cylinder; Coax., coaxial cylinder.

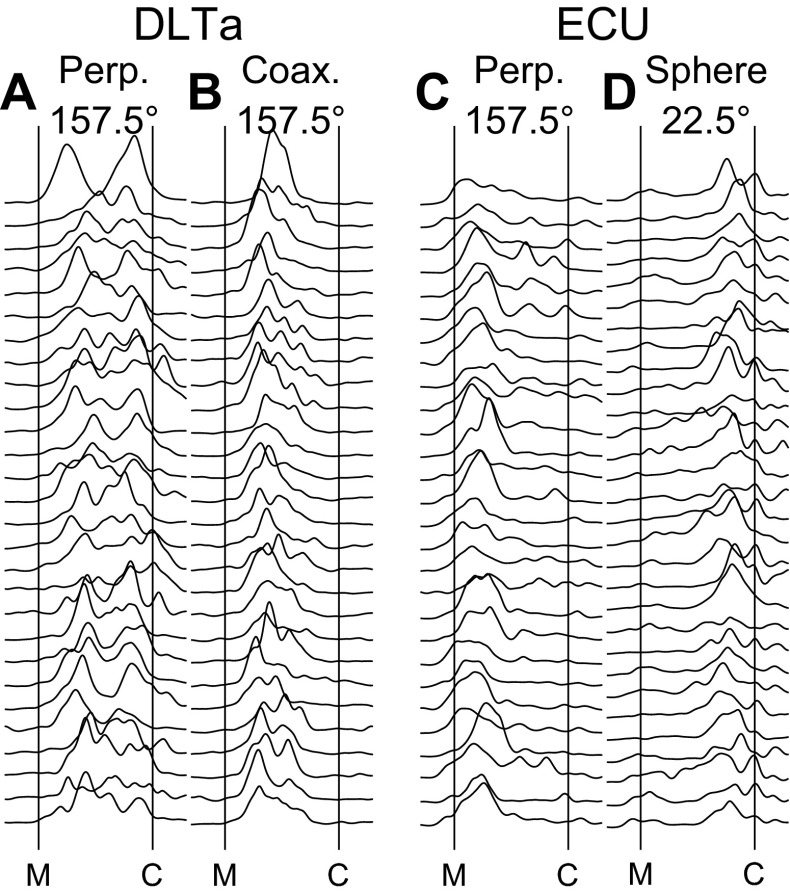

The duration from movement onset until contact with a peripheral object varied depending on both location and object, as well as from trial to trial for a given location–object combination. To permit a more accurate comparison across locations, objects, and trials, we therefore normalized the time from movement onset to contact with the peripheral object in each trial (see methods). Figure 2 shows selected examples of rastered individual trials of such time-normalized, full-wave-rectified, and smoothed EMG. DLTa, a shoulder muscle, showed prolonged activity during movements to the perpendicular cylinder at 157.5° (Fig. 2A). Although in some trials, the prolonged activity of DLTa appeared more or less continuous, in many trials, DLTa appeared to have both an early peak of activity after movement onset and a second, later peak before contact with the object. In contrast, during movements to the coaxial cylinder at the same location (Fig. 2B), DLTa showed only early activity, with little to no activity near the time of contact with the object. Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), a wrist muscle, by and large was active early during movements to the perpendicular cylinder at 157.5° (Fig. 2C), peaking shortly after movement onset and typically tapering off thereafter. However, during movement to the sphere at 22.5° (Fig. 2D), ECU was active later, typically increasing gradually and peaking shortly before contact. Although peaks of EMG activity thus varied in timing and magnitude amongst various muscles, and for a given muscle varied depending on location–object combination, examples such as these suggested that EMG activity across the extremity in general peaked in two phases during the present movements: once after movement onset and again before object contact.

Fig. 2.

Across-trial variability of EMG activity. For each of 2 selected muscles, DLTa and ECU, rasters are shown of time-normalized, full-wave-rectified, and smoothed EMG activity during multiple individual trials of successful movements for 2 selected location–object combinations. A: DLTa EMG during movements to the perpendicular cylinder located at 157.5°; B: DLTa, coaxial cylinder at 157.5°; C: ECU, perpendicular cylinder at 157.5°; D: ECU, sphere at 22.5°. All of these examples are from session L20120928. Time has been normalized to the median movement time (from M to C) across all trials in this session.

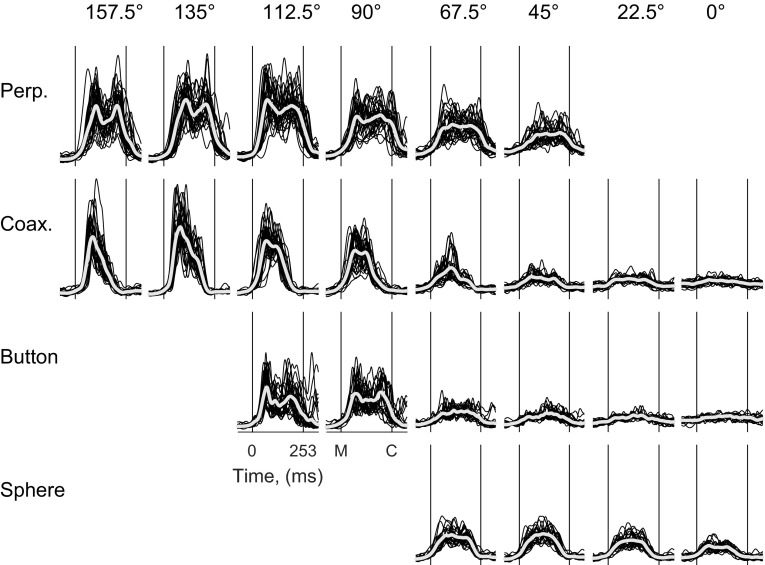

To obtain an overview of a particular muscle's EMG activity across an entire session, we overlapped these time-normalized, full-wave-rectified, and smoothed EMG traces from all of the individual trials for each location–object combination separately and plotted the overlapped trials for all 24 combinations, as illustrated in Fig. 3 for DLTa. In addition to showing the individual trials, the across-trial average has been superimposed for each combination. The EMG activity of DLTa clearly varied with both location and object, generally rising from baseline shortly after the onset of movement (M) and returning to baseline near the time of peripheral object contact (C). In addition, although not necessarily present in every individual trial (e.g., Fig. 2A), for several location–object combinations, DLTa, on average, appeared to have two temporally separate peaks of EMG activity. These two peaks were particularly evident, for example, during movements to the perpendicular cylinder at 157.5° and to the button at 112.5°. The first peak of activity occurred shortly after movement onset and the second shortly before contact with the peripheral object.

Fig. 3.

DLTa EMG activity for the 24 location–object combinations. EMG activity from DLTa is shown for all successful trials from a single recording session (L20120928). The duration of each trial has been normalized to 253 ms from movement onset (M) to object contact (C), the average duration of the reach-to-grasp epoch across all trials in this session. Individual trials (black traces) are shown, as well as their average (white traces), for each location–object combination. Two sequential peaks of EMG activity were evident in the average traces for several location–object combinations.

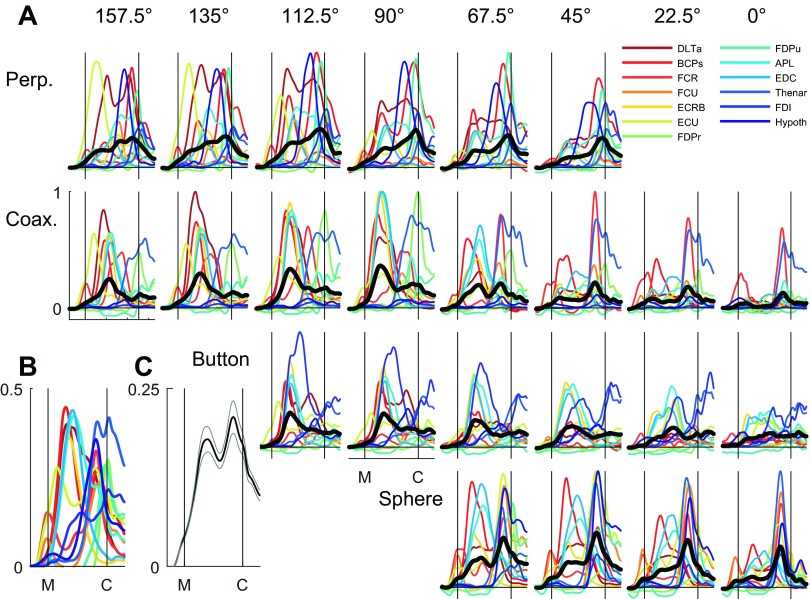

Averaging across multiple individual examples of EMG activity can emphasize their common modulation. To examine our impression of two phases further, we therefore normalized the amplitude of the time-normalized, smoothed, trial-averaged EMG (e.g., the across-trial averages in Fig. 3 for DLTa) separately for each muscle from 0 to 1, where 0 was assigned to the average premovement baseline, and 1 was assigned to the maximum trial-averaged value obtained in any of the 24 location–object combinations. These amplitude-normalized averages of EMG activity from each of the 13 muscles recorded in this session are shown in Fig. 4A for each of the 24 location–object combinations. We then averaged across the 13 muscles for each location–object combination. Although for any particular combination, the different muscles show a wide variety of EMG time courses, the across-muscle EMG averages again suggested two sequential peaks of EMG activity for many of the location–object combinations, with an early peak before the temporal midpoint of the reach-to-grasp epoch and a later peak just before peripheral object contact.

Fig. 4.

Averaged EMG activity. A: normalized EMG activity for each of 13 simultaneously recorded muscles (colored traces) is shown averaged across all successful trials for each of the 24 location–object combinations. For each combination, the black trace is the average across all 13 individual muscle averages. B: EMG activity for each muscle here has been averaged across all 24 combinations. C: grand average across all muscles and all location–object combinations, i.e., across all trials. Light gray lines indicate ±1 SE of the mean across the 24 location–object combination averages (black traces in A). Note that because EMG activity was relatively low much of the time in most muscles, the more the data were averaged, the lower the averaged values, and therefore, the ordinate scales differ in A (0–1), B (0–0.5), and C (0–0.25). All of the data shown here are from session L20120928.

Next, we averaged across all 24 location–object combinations for each muscle separately. Overlapped in Fig. 4B, these across-combination averages for each muscle again suggested an early and a late phase of EMG activity. Moreover, when considered as groups (Table 1), shoulder and elbow muscles, wrist muscles, and extrinsic and intrinsic finger muscles all showed peaks, both early and late. Finally, we averaged these traces to provide a grand average of the amplitude- and time-normalized EMG across all trials in all 24 location–object combinations and all muscles (Fig. 4C). This grand average shows that EMG activity generally increased from shortly before movement onset until contact with a peripheral object and declined thereafter. In addition to this broad ramping up and down of average EMG activity, two periods of a more-phasic increase were evident in the grand average: the first peaking early in the movement and the second peaking later before contact with a peripheral object, confirming the impression of two general phases of EMG activity in upper extremity muscles during the present movements.

Location, Object, and Interaction Effects in EMG Activity

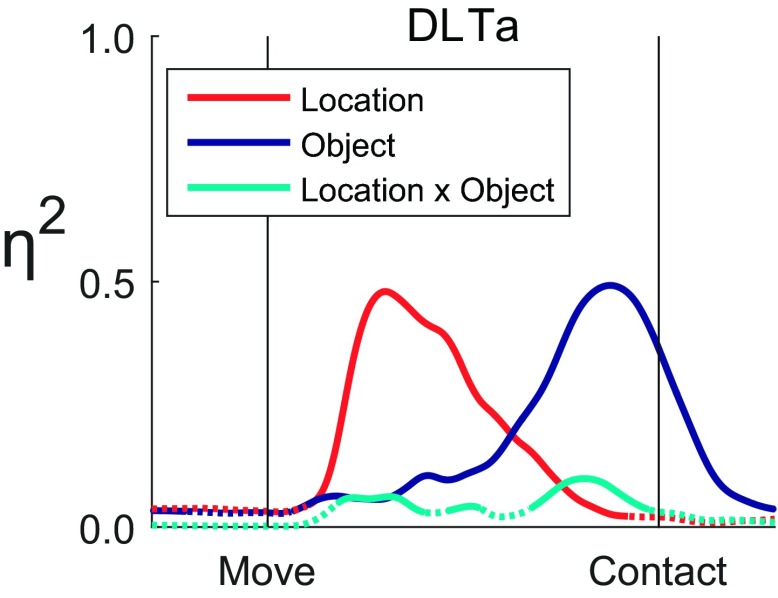

We used two-way ANOVA as a function of time to examine the effects of location and of object on the EMG activity of each muscle individually. Figure 5 shows effect size, η2, as a function of time for location, object, and location × object interaction across all 24 location × object combinations for the DLTa data presented in Fig. 3. Although all three types of effect began to increase at similar times after the onset of movement, the location effect became most substantial early in the movement and then waned after the temporal midpoint of the movements as the object effect grew—the latter reaching a maximum shortly before peripheral object contact. The interaction effect remained relatively small throughout. Although DLTa acts only across the shoulder and although the variation in EMG activity in DLTa was strongly dependent on location early in the reach-to-grasp epoch, the variation in DLTa EMG became more strongly dependent on object in the later phase of the movements.

Fig. 5.

Effect sizes, η2, as a function of time for the anterior deltoid (DLTa). The traces of effect size for location (red), object (blue), and their interaction (cyan) each are dotted when insignificant and solid when significant. An early peak in location effect was followed by a later peak in object effect, whereas the interaction effect remained comparatively small. Vertical lines indicate the time of movement onset (Move) and the time of contact with a peripheral object (Contact). The underlying data are shown in Fig. 3.

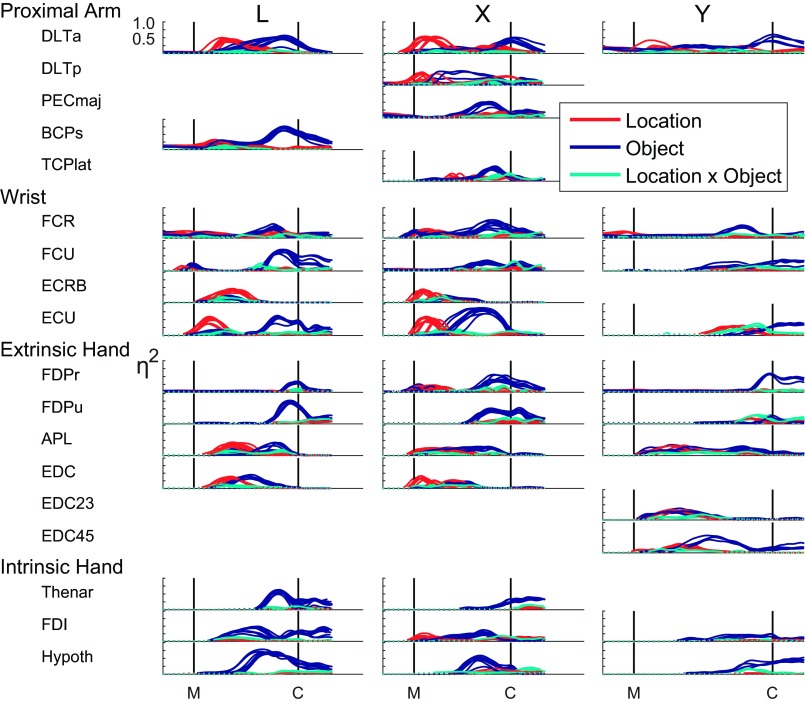

We applied ANOVA in this way to examine location, object, and interaction effect sizes as a function of time for each of the muscles recorded in each of the three monkeys in each session. As shown in Fig. 6, although the time courses of effects in any given muscle varied somewhat amongst the three monkeys, across sessions for a given monkey effects varied slightly in timing but otherwise were remarkably consistent. Nevertheless, an overall pattern was evident across muscles, sessions, and monkeys. In many muscles, an initial increase in the effect of location, sometimes beginning before movement onset, led to a peak location effect in the first half of the reach-to-grasp epoch. These initial peaks of location effect were present, not only in proximal muscles, such as DLTa, deltoid–posterior (DLTp), and BCPs, but also in wrist muscles, such as ECU and ECRB, and even in digit extensors, such as APL and EDC. In monkey X, even an intrinsic muscle of the hand, first dorsal interosseus (FDI), showed an early location effect that was present in multiple sessions. Initial location-related peaks were more common in monkeys L and X and were less common, smaller, and variably present in monkey Y, possibly related to this monkey's slower movements, which would have required less-intense bursts of EMG activity. Nevertheless, when location effects were substantial in monkey Y, they often occurred earlier than object effects, as seen in DLTa, flexor carpi radialis (FCR), and ECU.

Fig. 6.

Effect sizes, η2, plotted as a function of time for each muscle recorded in each of the 3 monkeys—L, X, and Y—in each session. In each plot, separate traces from each session from that monkey have been overlapped. In general, early variation in EMG activity depended primarily on location, whereas later variation depended primarily on object. Early location-related variation occurred not only in proximal muscles but also in many wrist and extrinsic hand muscles as well. Late, object-related variation in EMG activity occurred not only in distal muscles but also in shoulder and elbow muscles as well. The traces of effect size for location (red), object (blue), and their interaction (cyan) each are dotted when insignificant and solid when significant. Vertical lines indicate the time of movement onset (M) and the time of contact with a peripheral object (C). Here, the data from each session have been time normalized to that session's median movement time. Then, for each monkey, the traces from different sessions all have been scaled horizontally to a common time axis from M to C, based on the median movement times of the sessions marked with asterisks in Table 2. PECmaj, pectoralis major; TCPlat, triceps–lateral head.

In most muscles, any large location effect was declining by the temporal midpoint of the movement, and an object effect was rising, typically peaking before contact with the object. These later object-related effects were prominent, not only in distal finger muscles, such as the intrinsic muscles of the hand and the extrinsic finger flexors, FDPr and FDPu, where they typically constituted the only substantial effects, but also were evident in wrist muscles, including ECU, flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), and FCR, and even in proximal muscles, such as BCPs, pectoralis major (PECmaj), DLTp, and DLTa. Thus whereas not necessarily the case for every muscle individually, EMG activity overall showed initial variation that depended more strongly on location, followed by later variation that depended more strongly on object, with both proximal and distal muscles showing early location-related and later object-related effects.

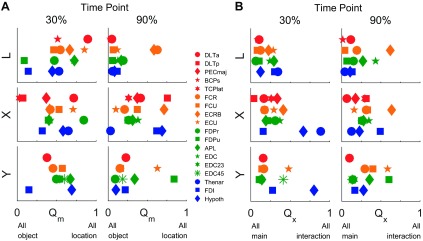

We used the quotient, Qm, at two time points (30% and 90%) between movement onset and contact with an object to quantify the relative effect of location vs. object on EMG activity. As shown in Fig. 7, at the 30% time point, location and object effects were comparatively balanced in all three monkeys with a slight tendency toward more of a location effect, such that Qm averaged across all muscles in each monkey was slightly >0.45 (mean ± SD: 0.54 ± 0.24 in monkey L, 0.46 ± 0.23 in X, and 0.50 ± 0.15 in Y). At the 30% time point, Qm was >0.5 for 8 of 13, 6 of 15, and 6 of 11 muscles in monkeys L, X, and Y, respectively. By the 90% time point, however, object effects had become generally greater than location effects, such that Qm averaged <0.4 in each monkey (0.17 ± 0.20 in L, 0.38 ± 0.22 in X, and 0.27 ± 0.24 in Y), with only three or four individual muscles having a Qm >0.5. At the 90% time point, Qm values were >0.5 for 2 of 13, 4 of 15, and 2 of 11 muscles in monkeys L, X, and Y, respectively. Thus at the 30% time point, location effects were prominent, but by the 90% time point, object effects predominated.

Fig. 7.

Quotients quantifying the relative size of location, object, and interaction effects at 2 points in time. Effects were compared at time points 30% and 90% of the normalized duration from movement onset to contact with a peripheral object. A: Qm quantifies location vs. object effect sizes. At the 30% time point, location and object main effects, on average, were similar in size. By the 90% time point, however, EMG activity in most muscles varied more in relation to object. B: Qx quantifies interaction vs. main effect sizes. The EMG activity of most muscles showed only modest interaction effects at either time point and thus depended primarily on the independent main effects of location and object. For each monkey, the data shown here were taken from the sessions marked with asterisks in Table 2.

We likewise quantified the size of the interaction effect (location × object) relative to the main effects of location and object at the 30% and 90% time points using the quotient, Qx. At both time points, Qx averaged <0.35 (at 30%: 0.18 ± 0.10 in L, 0.31 ± 0.22 in X, and 0.27 ± 0.22 in Y; at 90%: 0.18 ± 0.17 in L, 0.28 ± 0.14 in X, and 0.29 ± 0.18 in Y), indicating that interaction effects were relatively small. Only a few muscles showed interaction effects larger than the sum of the main location and object effects (Qx > 0.5), and these tended to be some of the more distal muscles. At the 30% time point, Qx was >0.5 for 0 of 13, 2 of 15, and 1 of 11 and then at the 90% time point, for 1 of 13, 1 of 15, and 2 of 11 muscles, in monkeys L, X, and Y, respectively. Hence, interaction effects generally were small throughout the reach-to-grasp epoch, indicating that the location and object main effects in EMG activity were relatively independent of one another.

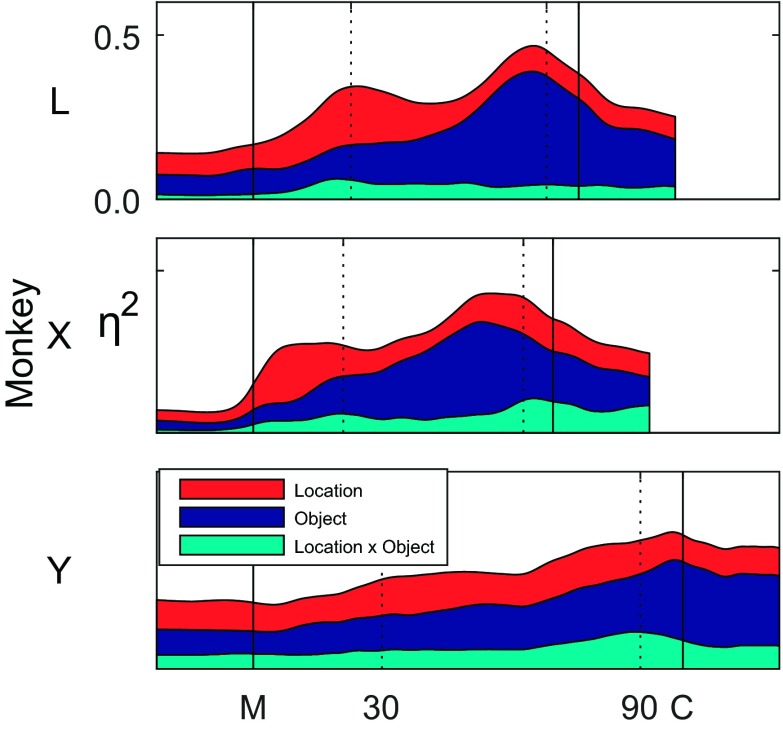

To provide a more continuous view of the total variation in location, object, and interaction effects, we plotted η2, averaged across all of the muscles as a function of time for one session from each of the three monkeys (Fig. 8). Here again, note that time was normalized separately for each monkey, such that the time scales reflect the interindividual differences in median movement times. The total variance explained by location, object, and their interaction increased from movement onset to object contact in each of the three monkeys. Whereas interaction effects generally were relatively small throughout the movements, early in the reach-to-grasp epoch, location effects were equivalent to or larger than object effects, but late in the movement, object effects became larger than location effects. In monkeys L and X, both of which tended to move faster than monkey Y, two sequential peaks of η2 were present, the first primarily in location effect size and the second primarily in object effect size. In monkey Y, these two peaks were less evident.

Fig. 8.

Location, object, and interaction effect sizes averaged across muscles. With the use of data from a single session from each monkey (marked with asterisks in Table 2), η2 values of each type were averaged across all recorded muscles as a function of time and stacked to represent the cumulative explained variance. Two sequential peaks in total η2 were evident, particularly in monkeys L and X. The first peak consisted of more location than object effect, whereas the second consisted largely of object effect. Interaction effects remained relatively small throughout.

Information about Location and Object in EMGs

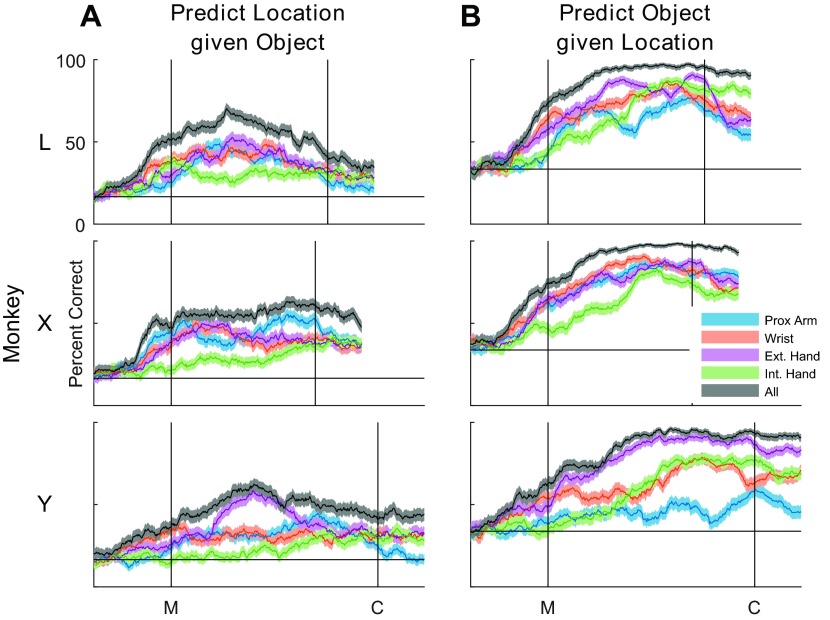

The fact that most muscles showed significant variation in EMG activity with both location and object suggested that proximal muscles had information about object, and conversely, distal muscles had information about location. We used LDA to assess the discriminable information present in different proximo-distal groups of muscles as a function of time during the present movements. We performed separate LDAs to classify location given the object (Fig. 9A) and to classify object given the location (Fig. 9B). In each monkey, the use of all of the muscles together gave the best prediction of either location or object. When predicting location, accuracy rose to a peak before the temporal midpoint of the reach-to-grasp epoch and declined thereafter in monkeys L and Y, although not in monkey X. In contrast, when predicting object, accuracy rose to a high plateau level before the temporal midpoint, and this level was maintained beyond the time of contact in all three monkeys. One might have expected shoulder muscles to provide a more-accurate prediction of location and the extrinsic and intrinsic finger muscles to provide a more-accurate prediction of object. However, other than the intrinsic muscles of the hand generally providing the poorest prediction of location, any such trends from proximal to distal muscle groups were minimal.

Fig. 9.

Linear discriminant analyses. Accuracy in predicting either location (A) or object (B) when the other factor is known was assessed using EMG activity from various proximodistal groups of muscles, defined in Table 1. For each muscle group and for all of the muscles used together, the solid line shows the percent correct averaged over 10-fold cross-validation, and the shaded region indicates 95% confidence intervals. Location prediction peaked shortly before the midpoint of the movements (M) and then declined. In contrast, object prediction rose until the midpoint and then maintained a high plateau beyond the time of peripheral object contact (C). Any systematic trends in prediction accuracy for either location or object were minimal. For each monkey, the data shown here were taken from the session marked with asterisks in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that muscle activity in the reach-to-grasp epoch of the present task occurred largely in two sequential phases. The averaging across all of the time- and amplitude-normalized EMGs recorded from proximal to distal muscles demonstrated two sequential peaks riding on a gradual increase in upper extremity EMG activity beginning before movement onset and not declining until contact with a peripheral object (Fig. 4C). The first of these peaks occurred before the temporal midpoint of the movement, with the midpoint being approximately the time at which the bell-shaped speed profile of hand transport reaches its maximum (cf. Fig. 2 in Rouse and Schieber 2015b). The second peak of EMG activity occurred just before peripheral object contact. As we found previously for joint angles, early variation in EMG activity was related predominately to location, whereas later variation was related predominately to object, with consistently small, although significant, location × object interactions.

Rather than a consistently biphasic pattern of EMG activity in any given muscle, these two temporal phases reflect the overall control of upper limb muscle activity by the nervous system. Although examples can be found in which a particular muscle was activated first early and again later in the same movement, in other cases a muscle was activated early for some location–object combinations and late for other combinations, and in still other cases a muscle was active only early or only late. Nevertheless, the averaging across all muscles and movements demonstrated two sequential peaks of muscle activation across the extremity. The variation in EMG activity across movements involving different locations and objects also was predominantly location related early and object related later. Furthermore, early location-related and later object-related variation was found in muscles from proximal to distal.

Whereas similar findings were obtained in all three monkeys, interindividual differences were present as well. Monkey Y, for example, moved more slowly than monkey L or X (Table 2). Although slower movement might have been expected to separate temporally sequential peaks, the slower movements of monkey Y involved more gradual modulation of EMG activity, as well as smaller location and object effects that were more dispersed in time, often resulting in less-prominent peaks in monkey Y than those seen in monkeys L and X. Variation in the EMG activity of ECU in monkeys L and X, for example, showed strong, distinct, early location-related and later object-related phases. However, in monkey Y, the location- and object-related variation of ECU was both comparatively small and delayed. Future studies, applying individualized models of the musculoskeletal system, will be needed to show how such interindividual differences in EMG patterns produce subtle differences in the kinematics and/or dynamics of arm and hand movements.

Location- and Object-Related Variation in Proximal and Distal Muscle EMG Activity

The EMG of proximal muscles certainly would be expected to vary with the location and orientation to which the hand must be transported in reaching. Our results are consistent with recent studies, however, in showing that EMG activity in proximal muscles also can vary depending on the object about to be grasped (Martelloni et al. 2009) and that such object effects are observable quite early in reaching movements (Fligge et al. 2013). Stark and colleagues (2007) found little, if any, object-related variation in shoulder and elbow muscle activity when objects were arranged in a horizontal plane, an orientation that they found elicited considerably less variation in proximal joints than when the same objects were arranged vertically. In contrast, in the present task, the four objects were arranged in a vertical, frontal plane, and the monkeys were required to manipulate each object differently, rather than consistently squeezing an immobile object. Consequently, in the present task, shoulder, elbow, and wrist joint angles all showed significant variation depending on the object about to be grasped (Rouse and Schieber 2015b), and EMG activity in shoulder, elbow, and wrist muscles likewise showed object-related variation. Object effects in proximal muscles thus may be understandably contingent on the variation in proximal joint angles required to grasp and manipulate different objects at the same location.

The EMG activity of distal muscles would be expected to vary with the object about to be grasped and manipulated. The EMG activity of the extrinsic digit flexors and the intrinsic muscles of the hand did vary prominently with object in the later phase of the reach-to-grasp epoch as the hand shaped to close on the object. Whereas these muscles showed little to no location-related variation, the EMG activity in other finger muscles, the extrinsic digit extensors (EDC and APL), did show location-related variation in the early phase as the hand opened and oriented toward the target location. Both the early location-related and later object-related variation in hand muscle EMG activity resembled the variation in joint angles of the hand. With the averaging of EMG activity across the entire movement epoch, Fig. 3B in Stark and colleagues (2007) similarly showed a combination of location and object effects in the EMG activity of extrinsic digit muscles. The grasping of the same object at different locations thus entails some degree of variation in hand muscle activity related not only to the object but also to its location.

The two phases of EMG activity described here resemble the early location-related and later object-related phases of variation that we described previously in the joint angles of the upper extremity during the same movements. The peaks of variation in EMG activity, however, seemed qualitatively more prominent than those in joint angle kinematics [cf. Fig. 8 in this paper vs. Fig. 7 of Rouse and Schieber (2015b)]. These peaks were particularly evident in the EMG activity of monkeys L and X, which performed the movements more quickly than in the EMG activity of monkey Y, which performed more slowly. Nevertheless, the enhanced prominence of the peaks in effect sizes for EMG activity compared with those for joint-angle kinematics was evident in all three monkeys. The more phasic variation in muscle activation—acting on the mass and internal viscosity of the limb first to project the arm and hand to a given location and then to shape the entire upper extremity for grasping the object—resulted in the external kinematic appearance of continuous, smooth motion throughout the extremity.

Implications for the Neural Control of Reach-to-Grasp Movements

The present findings support the hypothesis that at the level of muscle activation, reaching and grasping are controlled, in large part, sequentially rather than in parallel. The location- and object-related variation in EMG activity, like that described previously in joint angles, occurred predominantly in two serial phases. In the first phase, the predominantly location-related variation in the EMG activity of proximal muscles acted to move the shoulder, elbow, and wrist so as to transport and orient the hand toward the necessary location, whereas more distal muscles acted to open the hand in a location-dependent fashion. In this early phase, subtle object-related variations also occurred (especially apparent in the LDA; Fig. 9). In the second phase, the object-related variation in EMG activity of the extrinsic and intrinsic hand muscles acted to shape the hand so as to grasp the object appropriately, whereas object-related variation in more proximal muscles acted to locate and orient the hand as needed to achieve the appropriate grasp. Given that EMG activity is the final fast-conducting output of the neuromuscular system that will be smoothed by the inertia and viscosity of the limb, these observations suggest that during the present reach-to-grasp movements, the nervous system, in large part, acted initially to project the entire upper extremity toward the intended location and subsequently, to shape the entire extremity to grasp the object.

Three possible factors may contribute to these two phases of neural control. First, recent work has suggested that the neural activity controlling voluntary movement is intrinsically rhythmic at ∼3 Hz (Churchland et al. 2012; Hall et al. 2014). Thus the two phases of EMG activity described here may reflect an underlying rhythmicity in the neural control of the upper extremity musculature. Second, in the transition between the two phases, proprioceptive and visual feedback, returning from the initial phase of upper extremity motion, may be used to fine tune the output for the second phase. Third, the initial phase may be generated as a large amplitude movement with comparatively low precision, whereas the second phase may be optimized for finer control with higher precision (Rouse and Schieber 2015a).

The dorsal premotor cortex (PMd) has been studied most frequently during reaching (Cisek and Kalaska 2005; Hatsopoulos et al. 2004; Weinrich et al. 1984) and the ventral premotor cortex (PMv), most frequently during grasping (Carpaneto et al. 2011; Fluet et al. 2010; Raos et al. 2006; Rizzolatti et al. 1988; Spinks et al. 2008). A number of studies have shown, however, that many neurons in PMd and PMv vary their discharge in relation to both the location of reaching and the object grasped (Bansal et al. 2012; Raos et al. 2004; Stark et al. 2007; Wu and Hatsopoulos 2007), calling into question the notion that PMd controls reaching, whereas PMv controls grasping. In the macaque primary motor cortex, studies using intracortical microstimulation have shown the upper extremity representation to consist of a central core of digit representation surrounded by a “horseshoe” of more proximal representation (Kwan et al. 1978; Park et al. 2001). Although one might assume that neurons in the horseshoe of proximal representation discharge in relation to reach location, whereas those in the central core of digit representation discharge in relation to the object being grasped, our results raise the possibility that sequential location- and then object-related variation might occur in neurons throughout the primary motor cortex upper extremity representation.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by Grant R01 NS079664 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.G.R. and M.H.S. conception and design of research; A.G.R. and M.H.S. performed experiments; A.G.R. analyzed data; A.G.R. and M.H.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.G.R. prepared figures; A.G.R. drafted manuscript; A.G.R. and M.H.S. edited and revised manuscript; A.G.R. and M.H.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Andre Roussin and Jay Uppalapati for technical assistance and Marsha Hayles for editorial comments.

REFERENCES

- Bansal AK, Truccolo W, Vargas-Irwin CE, Donoghue JP. Decoding 3D reach and grasp from hybrid signals in motor and premotor cortices: spikes, multiunit activity, and local field potentials. J Neurophysiol 107: 1337–1355, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochier T, Spinks RL, Umilta MA, Lemon RN. Patterns of muscle activity underlying object-specific grasp by the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 92: 1770–1782, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buneo CA, Soechting JF, Flanders M. Muscle activation patterns for reaching: the representation of distance and time. J Neurophysiol 71: 1546–1558, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpaneto J, Umilta MA, Fogassi L, Murata A, Gallese V, Micera S, Raos V. Decoding the activity of grasping neurons recorded from the ventral premotor area F5 of the macaque monkey. Neuroscience 188: 80–94, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland MM, Cunningham JP, Kaufman MT, Foster JD, Nuyujukian P, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV. Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature 487: 51–56, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Neural correlates of reaching decisions in dorsal premotor cortex: specification of multiple direction choices and final selection of action. Neuron 45: 801–814, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika 26: 404–413, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- D'Avella A, Fernandez L, Portone A, Lacquaniti F. Modulation of phasic and tonic muscle synergies with reaching direction and speed. J Neurophysiol 100: 1433–1454, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AG, O'Dell R, Chan V, Schieber MH. Comparing effects in spike-triggered averages of rectified EMG across different behaviors. J Neurosci Methods 163: 283–294, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders M. Temporal patterns of muscle activation for arm movements in three-dimensional space. J Neurosci 11: 2680–2693, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders M, Herrmann U. Two components of muscle activation: scaling with the speed of arm movement. J Neurophysiol 67: 931–943, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders M, Pellegrini JJ, Geisler SD. Basic features of phasic activation for reaching in vertical planes. Exp Brain Res 110: 67–79, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fligge N, Urbanek H, van der Smagt P. Relation between object properties and EMG during reaching to grasp. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 23: 402–410, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluet MC, Baumann MA, Scherberger H. Context-specific grasp movement representation in macaque ventral premotor cortex. J Neurosci 30: 15175–15184, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TM, de Carvalho F, Jackson A. A common structure underlies low-frequency cortical dynamics in movement, sleep, and sedation. Neuron 83: 1185–1199, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsopoulos N, Joshi J, O'Leary JG. Decoding continuous and discrete motor behaviors using motor and premotor cortical ensembles. J Neurophysiol 92: 1165–1174, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. The formation of finger grip during prehension. A cortically mediated visuomotor pattern. Behav Brain Res 19: 99–116, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. The timing of natural prehension movements. J Mot Behav 16: 235–254, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan HC, MacKay WA, Murphy JT, Wong YC. Spatial organization of precentral cortex in awake primates. II. Motor outputs. J Neurophysiol 41: 1120–1131, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier MA, Hepp-Reymond MC. EMG activation patterns during force production in precision grip. I. Contribution of 15 finger muscles to isometric force. Exp Brain Res 103: 108–122, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelloni C, Carpaneto J, Micera S. Characterization of EMG patterns from proximal arm muscles during object- and orientation-specific grasps. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 56: 2529–2536, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 17: 857–872, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MC, Belhaj-Saif A, Cheney PD. Chronic recording of EMG activity from large numbers of forelimb muscles in awake macaque monkeys. J Neurosci Methods 96: 153–160, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MC, Belhaj-Saif A, Gordon M, Cheney PD. Consistent features in the forelimb representation of primary motor cortex in rhesus macaques. J Neurosci 21: 2784–2792, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raos V, Umilta MA, Gallese V, Fogassi L. Functional properties of grasping-related neurons in the dorsal premotor area F2 of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 92: 1990–2002, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raos V, Umilta MA, Murata A, Fogassi L, Gallese V. Functional properties of grasping-related neurons in the ventral premotor area F5 of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 95: 709–729, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Camarda R, Fogassi L, Gentilucci M, Luppino G, Matelli M. Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. II. Area F5 and the control of distal movements. Exp Brain Res 71: 491–507, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Schieber MH. Advancing brain-machine interfaces: moving beyond linear state space models. Front Syst Neurosci 9: 108, 2015a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Schieber MH. Spatiotemporal distribution of location and object effects in reach-to-grasp kinematics. J Neurophysiol 114: 3268–3282, 2015b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffelhofer S, Sartori M, Scherberger H, Farina D. Musculoskeletal representation of a large repertoire of hand grasping actions in primates. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 23: 210–220, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinks RL, Kraskov A, Brochier T, Umilta MA, Lemon RN. Selectivity for grasp in local field potential and single neuron activity recorded simultaneously from M1 and F5 in the awake macaque monkey. J Neurosci 28: 10961–10971, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark E, Asher I, Abeles M. Encoding of reach and grasp by single neurons in premotor cortex is independent of recording site. J Neurophysiol 97: 3351–3364, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towles JD, Valero-Cuevas FJ, Hentz VR. Capacity of small groups of muscles to accomplish precision grasping tasks. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013: 6583–6586, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Cuevas FJ. An integrative approach to the biomechanical function and neuromuscular control of the fingers. J Biomech 38: 673–684, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Cuevas FJ. Predictive modulation of muscle coordination pattern magnitude scales fingertip force magnitude over the voluntary range. J Neurophysiol 83: 1469–1479, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Cuevas FJ, Johanson ME, Towles JD. Towards a realistic biomechanical model of the thumb: the choice of kinematic description may be more critical than the solution method or the variability/uncertainty of musculoskeletal parameters. J Biomech 36: 1019–1030, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich M, Wise SP, Mauritz KH. A neurophysiological study of the premotor cortex in the rhesus monkey. Brain 107: 385–414, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Hatsopoulos NG. Coordinate system representations of movement direction in the premotor cortex. Exp Brain Res 176: 652–657, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]