Abstract

Background

Excitatory interneurons account for the majority of neurons in laminae I–III, but their functions are poorly understood. Several neurochemical markers are largely restricted to excitatory interneuron populations, but we have limited knowledge about the size of these populations or their overlap. The present study was designed to investigate this issue by quantifying the neuronal populations that express somatostatin (SST), neurokinin B (NKB), neurotensin, gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) and the γ isoform of protein kinase C (PKCγ), and assessing the extent to which they overlapped. Since it has been reported that calretinin- and SST-expressing cells have different functions, we also looked for co-localisation of calretinin and SST.

Results

SST, preprotachykinin B (PPTB, the precursor of NKB), neurotensin, PKCγ or calretinin were detected with antibodies, while cells expressing GRP were identified in a mouse line (GRP-EGFP) in which enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was expressed under control of the GRP promoter. We found that SST-, neurotensin-, PPTB- and PKCγ-expressing cells accounted for 44%, 7%, 12% and 21% of the neurons in laminae I–II, and 16%, 8%, 4% and 14% of those in lamina III, respectively. GRP-EGFP cells made up 11% of the neuronal population in laminae I–II. The neurotensin, PPTB and GRP-EGFP populations showed very limited overlap, and we estimate that between them they account for ∼40% of the excitatory interneurons in laminae I–II. SST which is expressed by ∼60% of excitatory interneurons in this region, was found in each of these populations, as well as in cells that did not express any of the other peptides. Neurotensin and PPTB were often found in cells with PKCγ, and between them, constituted around 60% of the PKCγ cells. Surprisingly, we found extensive co-localisation of SST and calretinin.

Conclusions

These results suggest that cells expressing neurotensin, NKB or GRP form largely non-overlapping sets that are likely to correspond to functional populations. In contrast, SST is widely expressed by excitatory interneurons that are likely to be functionally heterogeneous.

Keywords: Dorsal horn, somatostatin, neurotensin, neurokinin B, gastrin-releasing peptide

Background

Defining the neuronal circuitry within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord is important because this region contains the first synapse in the pain and itch pathways and is a site at which significant modulation of nociceptive, and pruritoceptive transmission can occur.1–8 A crucial factor that has limited our understanding of this circuitry is the complex organisation of interneurons, which account for the great majority of neurons in laminae I–III.2,7,9,10 Interneurons in these laminae are diverse in terms of their structure and function.11–20 They can be divided into two main groups: inhibitory (GABAergic and/or glycinergic) and excitatory (glutamatergic) neurons.2 There have been several attempts to define functional populations among these cells, but although combined electrophysiological and morphological approaches have demonstrated that certain interneuron classes can be recognised in each lamina,11,19,20 these have failed to provide a comprehensive classification scheme that can be used as a basis for defining the neuronal circuitry of the region.

Laminae I–III contain a diverse array of neurochemical markers, including various neuropeptides and their receptors, together with other proteins, such as calcium-binding proteins, the γ isoform of protein kinase C (PKCγ) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS).1,2,21 Each of these peptides/proteins is expressed by specific populations of neurons: in some cases, they are restricted to either excitatory or inhibitory cells, while in others, they can be found among both types. Recent studies have defined four largely non-overlapping populations among the inhibitory interneurons, based on expression of neuropeptide Y, parvalbumin, nNOS or galanin/dynorphin.22–24 Between them, these populations account for over half of the inhibitory interneurons in laminae I–II, and they show distinct developmental and functional properties.24–28

Much less is known about the organisation of excitatory interneurons, although it has been demonstrated that some of those in lamina II can be assigned to one of two morphological classes: vertical and radial cells.11,14,15,17,29,30 Several neurochemical markers have been shown to be mainly or completely restricted to the excitatory interneurons, including the neuropeptides somatostatin (SST), neurotensin, neurokinin B (NKB) and gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), the calcium-binding proteins calbindin and calretinin and PKCγ.12,28,31–43 However, our knowledge about the pattern of co-localisation of these different markers is incomplete. In the rat, it has been reported that there is overlap between SST and NKB, but that neither of these are co-expressed with neurotensin, and that all three peptides are found in some PKCγ-immunoreactive neurons.32,35,43 In the mouse, GRP is thought to be expressed in cells with SST, but not those with NKB and shows limited overlap with PKCγ.36,44

Recent studies have suggested specific roles for certain neurochemically defined populations of excitatory interneurons in pain mechanisms. For example, it has been proposed that the PKCγ cells are involved in transmission of input from myelinated low threshold mechanoreceptors to lamina I projection neurons, thus contributing to tactile allodynia in chronic pain states.45 In addition, Duan et al.25 reported that ablating the SST-expressing cells (but not NKB or calretinin neurons) resulted in loss of mechanical pain. It is, therefore, important to define the patterns of expression of these neurochemical markers among the excitatory interneurons, as this may provide evidence for specific functional populations, as was shown to be the case for the inhibitory interneurons.22 The main aims of the present study were to quantify the neurons that express SST, NKB, neurotensin, GRP and PKCγ in the mouse, assess the extent of overlap between these populations and determine the proportion of excitatory interneurons that they account for. Because of the reported difference between the effects of ablating SST- and calretinin-expressing cells,25 we also tested the extent to which SST and calretinin were co-localised.

Methods

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Review Process Applications Panel of the University of Glasgow and were performed in accordance with the European Community directive 86/609/EC and the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Animals and general features of tissue processing

Five adult wild-type male C57Bl/6 mice (24-33 g) and 6 Tg(GRP-EGFP) mice of either sex (21–31 g) (GENSAT)36,46 were deeply anaesthetised with pentobarbitone (30 mg i.p.) and perfused through the left ventricle with fixative that contained 4% freshly depolymerised formaldehyde in 0.1 M PB. Mid-lumbar spinal cord segments (L4 and L5) were dissected out and stored for 2–4 h in the same fixative. They were then cut into transverse sections with a vibrating-blade microtome and immersed in 50% ethanol for 30 min to enhance antibody penetration. Multiple-labelling immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously.27,36,47 Briefly, sections were incubated for 1–3 days at 4℃ in primary antibodies diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) that contained 0.3 M NaCl and 0.3% Triton X-100. They were then incubated overnight in species-specific secondary antibodies that were raised in donkey and conjugated to Alexa 488, Alexa 647, Rhodamine Red, Pacific Blue or biotin (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). All secondary antibodies were diluted 1:500 (in the same diluent), apart from those conjugated to Pacific Blue or Rhodamine Red, which were diluted 1:200 and 1:100, respectively. Biotinylated secondary antibodies were detected either with Pacific Blue conjugated to avidin (1:1000; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK), or with a tyramide signal amplification (TSA) method (TSA kit tetramethylrhodamine NL702, PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA). The TSA reaction was used to detect the antibody against preprotachykinin B (PPTB, the precursor for NKB), as this method can reveal the cell bodies of neurons that express NKB.35,48

The GRP-EGFP mouse was used to allow identification of presumed GRP-expressing cells in the superficial dorsal horn because the level of GRP in cell bodies of these neurons is below the limit of detection with immunocytochemistry.44 Solorzano et al.44 have demonstrated that 93% of the lamina II EGFP-positive cells in this mouse contain mRNA for GRP.

Quantification of populations expressing PKCγ and neuropeptides

To determine the proportion of neurons in each of laminae I–III that expressed PKCγ, SST, neurotensin, or NKB, sections from three wild-type animals were reacted with a mixture of primary antibodies, consisting of anti-PKCγ (guinea pig or rabbit antibodies) and NeuN, together with antibody against one of the following: SST, neurotensin (rabbit or rat antibodies) or PPTB. Following the immunocytochemical reaction, the sections were incubated in DAPI to label cell nuclei. To determine the proportion of neurons in each lamina that were EGFP-positive in the GRP-EGFP mice, sections from three of these animals were reacted with antibodies against EGFP, PKCγ (guinea pig) and NeuN, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies and nuclear staining with DAPI.

In each case, a modification49 of the optical disector method50 was used to obtain an unbiased sample of neurons in laminae I–II and lamina III. For each antibody combination, two sections were selected before immunostaining for the corresponding peptide was viewed. These were scanned with a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope equipped with Argon multi-line, 405 nm diode, 561 nm solid state and 633 nm HeNe lasers and a spectral detection system. Confocal image stacks were acquired by scanning through a 40× oil-immersion lens (numerical aperture 1.3) with the aperture set to 1 Airy unit, and in each case, these consisted of 30 optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing. The confocal image stacks were analysed with Neurolucida for Confocal software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA) as described previously.23,51–53 The border between laminae II and III was defined as the ventral limit of the plexus of PKCγ dendrites that occupies the inner half of lamina II, and this was added to the Neurolucida drawings. We have shown that in the rat, the dense plexus of PKCγ dendrites occupies the inner half of lamina III, and that its ventral limit corresponds closely to the lamina II/III border defined by dark-field illumination.54 The lamina III/IV border was identified by the somewhat lower packing density of neurons in lamina IV.55 Throughout this study, we grouped laminae I and II together, and we therefore did not define the lamina I–II border. In each confocal z-stack, the 15th and 24th optical sections were taken as the reference and look up sections, and all neuronal nuclei (defined by the presence of NeuN and DAPI staining) that had their bottom surface between these sections were plotted onto the drawing. In all cases in which the disector method was used, we carefully examined staining in all optical sections between the look-up and reference sections and added the locations of any cells that were entirely contained between these two sections.49 The channel corresponding to the neuropeptide (SST, neurotensin or PPTB) or EGFP (in the GRP-EGFP tissue) was then viewed, and the presence or absence of staining was recorded for each of the selected neurons. For the tissue from wild-type mice, the PKCγ channel was then viewed, and all PKCγ-immunoreactive neurons were identified among the sample of selected neurons. The PKCγ analysis was not performed on the GRP-EGFP tissue because we have previously reported that there is limited co-localisation between EGFP and PKCγ in this mouse line.36 In this way, we determined the proportions of neurons in laminae I–II and in lamina III that were immunoreactive for each of the peptides or PKCγ, as well as the extent of co-localisation of PKCγ with SST, neurotensin and PPTB.

Assessment of co-localisation of the neuropeptides

To determine the extent of overlap between SST, neurotensin and GRP-EGFP populations, sections from three GRP-EGFP mice were immunoreacted with antibodies against EGFP, SST, neurotensin (rat antibody) and NeuN. Two sections from each mouse were selected and scanned with the confocal microscope as described above, except that z-stacks through the full thickness of the section were obtained. The outline of the dorsal horn was drawn with Neurolucida, and the lamina borders were identified and plotted as above, except that in this case, the ventral border of the plexus of SST-immunoreactive profiles was used to define the border between laminae II and III. In analysing sections immunostained for both SST and PKCγ (see above), we had found that the ventral borders of both PKCγ-immunoreactive and SST-immunoreactive plexuses were in the same location (Figure 1). The optical disector technique was initially used to select SST-immunoreactive cells. All SST-immunoreactive neurons that had the bottom of their cell bodies between reference and look-up sections (15th and 24th optical sections, respectively) were plotted onto the Neurolucida drawing. In some cases, NeuN staining extends into proximal dendrites, but these could be recognised because of their reduced diameter, compared to the cell bodies from which they originated. The channels corresponding to neurotensin and EGFP were then viewed, and the presence or absence of each type of staining was recorded for each of the selected SST-immunoreactive cells. The same z-stacks were then re-analysed to identify first the neurotensin-immunoreactive and then the EGFP-positive cells. However, because the neurotensin and GRP-EGFP populations are smaller than the SST population, we increased the size of the disector (i.e. the separation between reference and look-up sections) to between 18 and 30 µm in order to increase the number of cells sampled. In this way, we determined the proportion of neurotensin-immunoreactive cells that were SST-immunoreactive and/or EGFP-positive, and the proportion of EGFP-positive cells that were SST- and/or neurotensin-immunoreactive.

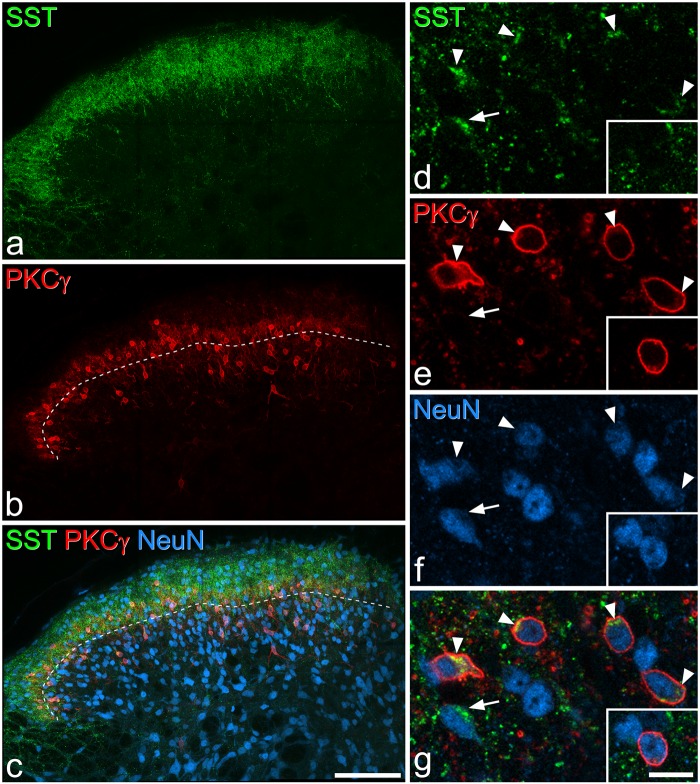

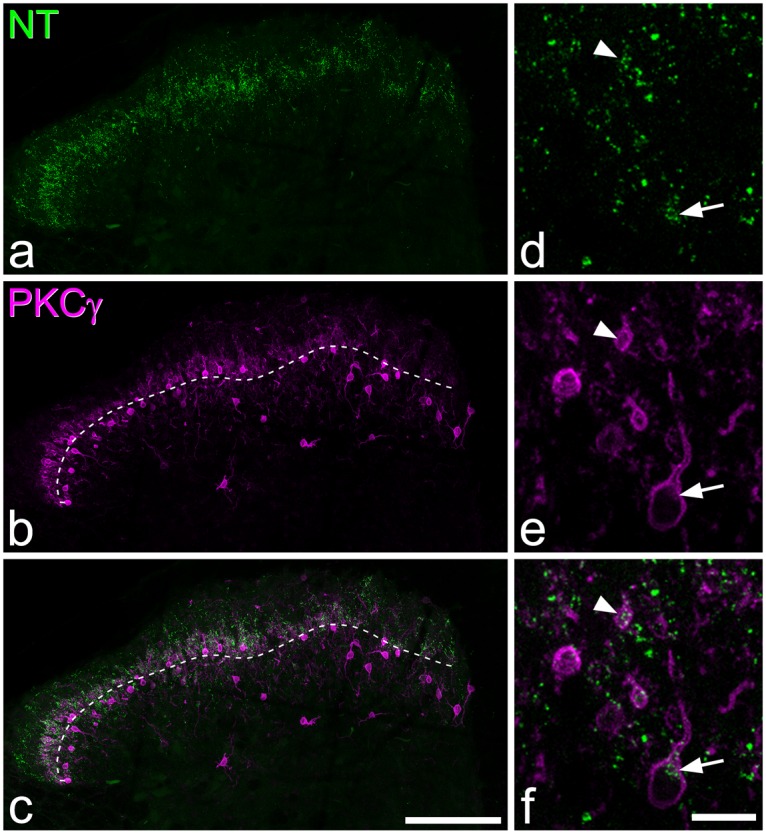

Figure 1.

SST and PKCγ immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining with antibodies against SST (green), PKCγ (red), and NeuN (blue) in a projection of 30 optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing. The dashed line in (b) and (c) represents the lamina II-III border. SST immunoreactivity occupies a dense band in laminae I–II, while PKCγ cells are concentrated in the inner part of lamina II and lamina III. (d–g) show a higher magnification view of a single optical section. Five SST-immunoreactive cells can be seen: four of these (arrowheads) are also PKCγ-immunoreactive, while one (arrow) is not. The inset shows a nearby cell that is PKCγ-immunoreactive, but lacks SST. Scale bars: (a–c) = 100 µm, (d–g) = 10 µm.

Co-localisation of SST and PPTB was quantified in sections from three wild-type mice that had undergone an immunoreaction with antibodies against SST, PPTB and NeuN. The selection, scanning and analysis was performed exactly as described earlier, with a 10 µm disector to select SST-immunoreactive cells, and a 20–25 µm disector to select PPTB-positive cells. Again, we determined the proportion of SST cells that were PPTB-positive, and vice versa.

Co-localisation between neurotensin and PPTB was assessed in sections from three wild-type mice that had been immunoreacted with antibodies against neurotensin (rat), PPTB, PKCγ (rabbit) and NeuN. The sections were selected, scanned and analysed as described earlier, except that the PKCγ plexus was used to define the lamina II/III border and the disector separation was between 20 and 25 µm. Initially, PPTB-immunoreactive neurons with the bottom surface of their cell bodies between reference and look-up section were analysed, and then the neurotensin channel was viewed and the proportion of the selected PPTB-immunoreactive cells that were also neurotensin-immunoreactive was determined. The sequence was then reversed, and we determined the proportion of neurotensin-immunoreactive cells that were also PPTB-immunoreactive.

To look for possible co-localisation of PPTB and EGFP in the GRP-EGFP mouse, sections from three of these animals were reacted with antibodies against EGFP, PPTB, PKCγ and NeuN. A single section from each animal was selected and scanned as described earlier. The lamina II/III border was identified from the PKCγ plexus, and sections were searched for possible co-localisation between PPTB-immunoreactivity and EGFP.

Co-localisation of SST and calretinin

This was assessed in sections from three wild-type mice that were reacted with antibodies against SST, calretinin, NeuN and then stained with DAPI to reveal cell nuclei. Sections were selected and scanned as described earlier. The lamina borders were plotted onto an outline of the dorsal horn with Neurolucida, and the laminar boundaries defined as described previously. Initially, we selected all SST-immunoreactive neurons in laminae I–II for which the bottom of the nucleus was located between the 15th and 24th optical sections, and then viewed the calretinin channel to determine the proportion that were calretinin-immunoreactive. We then used the same approach to select calretinin-immunoreactive neurons and determine the proportion that were SST-immunoreactive.

Characterisation of antibodies

A list of the sources and dilutions of primary antibodies used in the study is given in Table 1. The somatostatin antiserum is reported to show 100% cross-reactivity with somatostatin-28 and somatostatin-25, but none with substance P, neuropeptide Y or vasoactive intestinal peptide (manufacturer’s specification), and we have shown that staining with this antibody is abolished by pre-incubation with 10 µg/ml somatostatin.32 The rabbit antibody against neurotensin shows no cross-reactivity with kinetensin, substance P or bombesin (manufacturer’s specification), and staining is blocked by pre-incubation with 10 µg/ml neurotensin.31 Staining with the rat antiserum against neurotensin in the rat brain is identical to that seen with a well-characterised rabbit antiserum and is blocked by pre-incubation with 10−4 M neurotensin.56 The PPTB antibody was raised against amino acids 95–116 of the rat PPTB48 and detects PPTB (but not substance P, neurokinin A or NKB) on dot blots. Immunostaining is abolished on both dot blots and tissue sections by pre-incubation with the peptide against which the antibody was raised.48 The guinea pig antibody against PKCγ was raised against the C terminal 14 amino acids of the mouse protein and recognises a single band of the appropriate molecular weight on Western blots of brain homogenates from wild-type, but not PKCγ−/− mice.57 The rabbit PKCγ antibody is directed against the C-terminus of the mouse protein, and we have shown that it stains identical structures to the guinea-pig PKCγ antibody.52 The calretinin antibody was produced against human recombinant calretinin and does not stain the brain of calretinin knock-out mice (manufacturer’s specification). The EGFP antibody was raised against recombinant full-length EGFP, and its distribution matched that of the EGFP. The mouse monoclonal antibody NeuN reacts with a protein in cell nuclei extracted from mouse brain,58 which has subsequently been identified as the splicing factor Fox-3.59 NeuN apparently labels all neurons but no glial cells in the rat spinal dorsal horn.60

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used in this study.

| Antibody | Species | Catalogue no | Dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatostatin | Rabbit | T-4103 | 1:1,000 | Peninsula |

| Neurotensin | Rabbit | IHC7351 | 1:1,000 | Peninsula |

| Neurotensin | Rat | 1:1,000 | P Ciofi | |

| PPTB | Guinea pig | 0.016 µg/ml* | T Furuta/T Kaneko | |

| PKCγ | Rabbit | sc211 | 1:1,000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| PKCγ | Guinea pig | 1:500 | M Watanabe | |

| Calretinin | Goat | CG1 | 1:1,000 | Swant |

| EGFP | Chicken | ab13970 | 1:1,000 | Abcam |

| NeuN | Mouse | MAB377 | 1:500-1000 | Millipore |

PPTB was detected with tyramide signal amplification.

Results

In all immunoreactions used throughout the study, antibody penetration appeared to be complete because immunoreactive cells were found through the depth of the section, and there was no obvious reduction in their number in the middle of the sections.

Distribution and frequency of cells expressing SST, neurotensin, PPTB or GRP-EGFP and their coexpression with PKCγ

The distribution of cells that were immunoreactive for each of these markers was similar to what has been reported in previous studies in mouse and rat.31,32,35,36,43,44,46,54,61–65 Quantitative results from this part of the study are shown in Tables 2 and 3 and examples of immunostaining in Figures 1–3.

Table 2.

Proportions of neurons immunoreactive for neuropeptides or GRP-EGFP.

| Laminae I–II |

Lamina III |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of neurons counted | Number of IR neurons | % of neurons that were IR | Estimated % of excitatory neurons that were IR | Total number of neurons counted | Number of IR neurons | % of neurons that were IR | Estimated % of excitatory neurons that were IR | |

| SST | 294 (259–333) | 129 (112–152) | 43.8 (42.4–45.6) | 59 | 146.3 (144–150) | 23.7 (20–27) | 16.2 (13.8–18) | |

| Neurotensin | 304.3 (294–310) | 20.3 (19–22) | 6.7 (6.1–7.1) | 9 | 144.3 (128–161) | 11.3 (8–14) | 7.8 (6.3–9.7) | 12.5 |

| PPTB | 350 (335–374) | 40.7 (33–47) | 11.6 (9.9–12.6) | 15.6 | 152 (134–174) | 6.3 (4–8) | 4.1 (3–4.7) | 6.6 |

| GRP–EGFP | 616 (613–618) | 68 (63–72) | 11 (10.2–11.8) | 14.8 | ||||

The table shows the total number of neurons counted, together with the number and percentage that were immunoreactive (IR) for each peptide. GRP-EGFP cells were rarely seen in lamina III and so were not counted in this lamina. In each case, the mean values for three mice are shown, with the range in brackets. The estimates of percentage of excitatory neurons in each lamina that were accounted for by each neurochemical population are based on the data from literature.73 Because an unknown proportion of SST cells in lamina III are inhibitory (GABAergic/glycinergic25,32), the proportion has not been estimated for SST cells in lamina III.

Table 3.

Co-expression of peptides with PKCγ.

| Laminae I–II |

Lamina III |

Laminae I–III |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PKCγ-IR cells examined | % of peptide-IR that are PKCγ-IR | % of PKCγ-IR that are peptide-IR | Number of PKCγ-IR cells examined | % of peptide-IR that are PKCγ-IR | % of PKCγ-IR that are peptide-IR | Number of PKCγ-IR cells examined | % of peptide-IR that are PKCγ-IR | % of PKCγ-IR that are peptide-IR | |

| SST | 60.3 (52–71) | 34.6 (34.1–34.9) | 74.2 (67.2–80.8) | 21.3 (16–28) | 49.8 (40–59.3) | 55.7 (50–60) | 81.7 (68–91) | 33.9 (25.2–39.6) | 62.8 (52.9–71.4) |

| Neurotensin | 62 (59–67) | 96.8 (95–100) | 31.7 (31.3–32.2) | 20.3 (11–27) | 78.6 (50–100) | 44.6 (34.8–54.5) | 82.3 (78–86) | 89.9 (79.4–96.4) | 34.4 (32.5–36) |

| PPTB | 78 (59–88) | 60.3 (54.5–66.7) | 31.3 (30–32.2) | 19.3 (14–24) | 46.4 (14.3–75) | 12.9 (7.1–16.7) | 97.7 (74–112) | 57.7 (47.5–67.4) | 27.7 (25.7–29) |

The table shows the total number of PKCγ-immunoreactive (-IR) neurons that were counted, the percentage of peptide-immunoreactive neurons that were PKCγ-immunoreactive, and the percentage of PKCγ-immunoreactive neurons that were peptide-immunoreactive, in laminae I–II, lamina III, and laminae I–III. In each case, the mean values for three mice are shown, with the range in brackets. Data for co-existence of PKCγ and GRP-EGFP are not included, as this has been reported previously.36

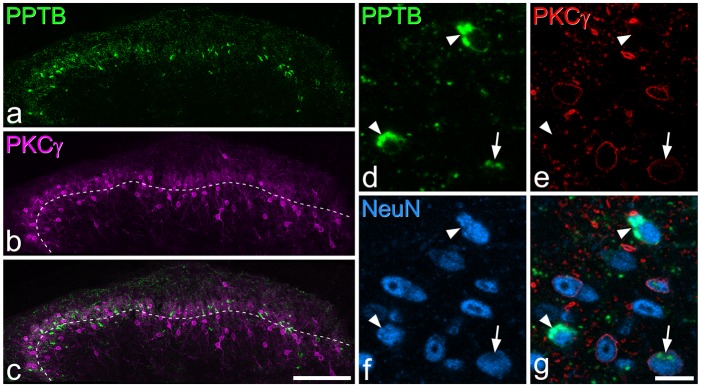

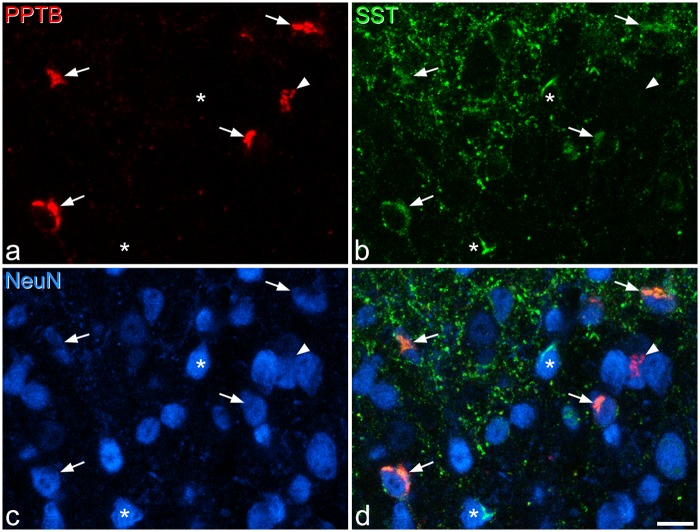

Figure 2.

Neurotensin and PKCγ immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining with antibodies against neurotensin (NT, green) and PKCγ (magenta) in a projection of 18 optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing. The dashed line in (b) and (c) represents the lamina II-III border. Neurotensin immunoreactivity forms a plexus in lamina IIi and III, which overlaps the distribution of PKCγ immunostaining. (d-f) show a higher magnification view of a projection of three optical sections. A neurotensin-immunoreactive cell that is also PKCγ-immunoreactive is indicated with an arrow, while the proximal dendrite of another neurotensin-immunoreactive PKCγ cell can also be seen (arrowhead). Scale bars: (a–c) = 100 µm, (d–f) = 10 µm.

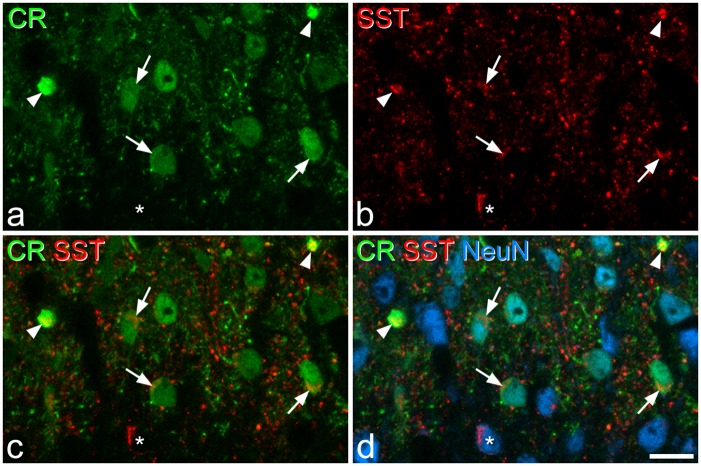

Figure 3.

PPTB and PKCγ immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining with antibodies against PPTB (green) and PKCγ (magenta) in a projection of 30 optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing. The dashed line in (b) and (c) represents the lamina II-III border. PPTB immunoreactivity is present in numerous profiles in lamina IIi, which correspond to cell bodies. (d–g) show a higher magnification view of a single optical section. Three PPTB-immunoreactive cells can be seen in this field, of which one (arrow) is weakly immunoreactive for PKCγ and two (arrowheads) are PKCγ-negative. Scale bars: (a–c) = 100 µm, (d–g) = 10 µm.

PKCγ-immunoreactive neurons were concentrated in laminae IIi and III, although scattered cells were seen dorsal and ventral to this region (Figures 1–3). Immunostaining was present in the somatic plasma membrane and extended into dendrites, which formed a dense plexus that occupied lamina IIi, as described previously.54 As in the rat,35 there was considerable variation in the intensity of immunostaining between PKCγ-immunoreactive cells. We estimated the proportion of neurons in laminae I–II and in lamina III that were PKCγ-immunoreactive by using the disector method in three sets of sections: those reacted with antibodies against SST, neurotensin or PPTB in combination with NeuN, anti-PKCγ and DAPI staining. The total numbers of PKCγ-immunoreactive neurons identified in this part of the study were 601 in laminae I–II and 183 in lamina III. The results were highly consistent across the three sets of sections: PKCγ neurons corresponded to 21% of all neurons in laminae I–II (range 20.4%–22.2%) and 13.9% (12.7%–14.5%) of those in lamina III.

Immunostaining with the SST antibody formed a dense band in laminae I–II, with scattered profiles in lamina III (Figure 1). Immunoreactive cell bodies were difficult to see at low magnification because of the very high density of other profiles, which correspond mainly to axonal boutons. However, they were readily visible at high magnification, with the SST-immunoreactivity occupying part of the perikaryal cytoplasm, either surrounding the nucleus or forming discrete clumps of staining that were asymmetrically distributed around the nucleus (Figures 1d–f, 4a,f and 7c,f). This pattern presumably corresponded to staining within the Golgi apparatus. The SST-immunoreactive neurons were particularly numerous and were most densely packed in the superficial laminae, with a lower number being present in lamina III. SST-immunoreactive cells accounted for 44% of all neurons in laminae I–II and 16% of those in lamina III (Table 2). Throughout laminae I–III, 34% of SST-immunoreactive cells were also PKCγ-immunoreactive, and these accounted for 63% of the PKCγ cells (Table 3).

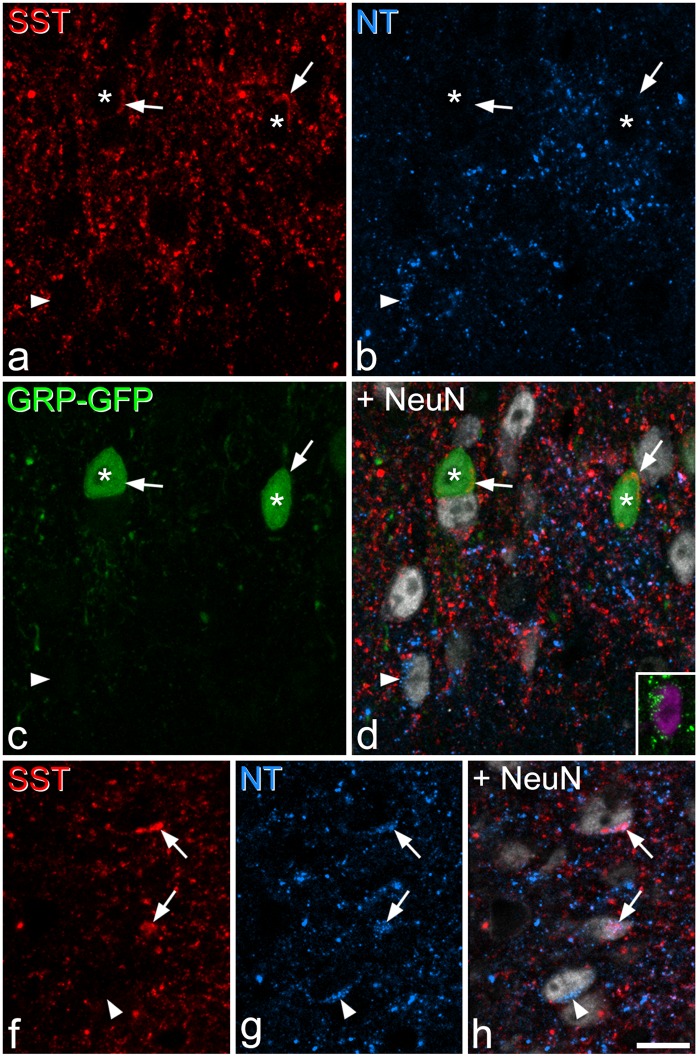

Figure 4.

SST, neurotensin, and EGFP immunoreactivity in a section from a GRP–EGFP mouse. (a–d) Immunostaining with antibodies against SST (red), neurotensin (NT, blue), EGFP (green), and NeuN (grey) in a projection of three optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing shows two EGFP+ cells (asterisks) that contain SST immunoreactivity (indicated with arrows). The arrowhead marks a neurotensin-expressing neuron – the neurotensin immunoreactivity is seen as a cluster of blue puncta. The inset shows this cell in a projection of eight optical sections, with neurotensin in green and NeuN in magenta. (e–g) Part of the same section scanned to reveal SST, neurotensin, and NeuN. This image which is a projection of three optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing, includes three cells that are neurotensin-immunoreactive. Two of these (arrows) are also SST-immunoreactive, while the third one (arrowhead) lacks SST. Scale bar = 10 µm.

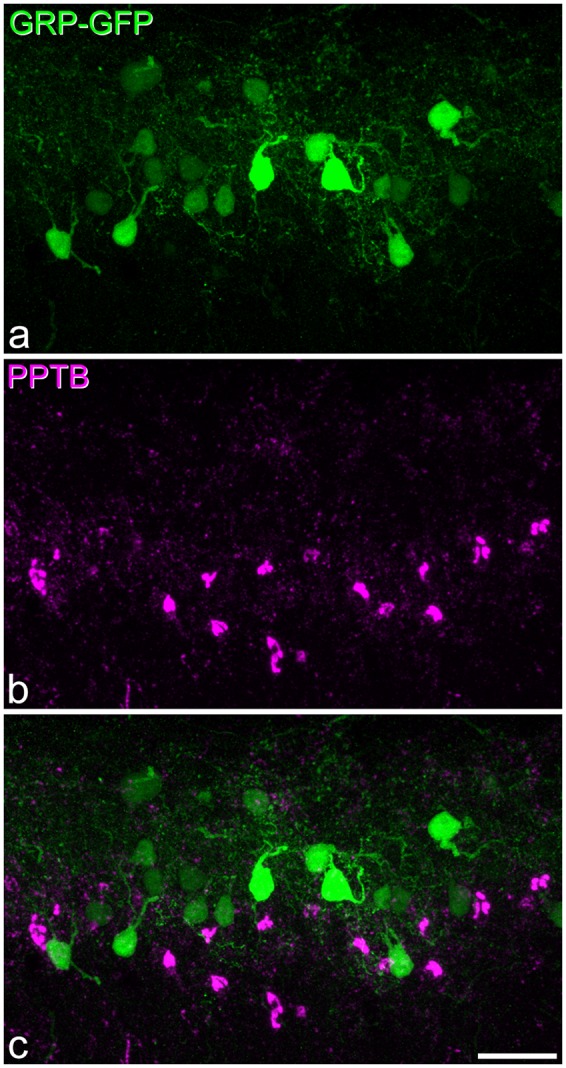

Figure 7.

PPTB and EGFP immunoreactivity in a section from a GRP-EGFP mouse. (a,b) Immunostaining for EGFP (green) and PPTB (magenta) in a maximum intensity projection of 27 optical sections at 1 µm z-spacing. (c) A merged image. Numerous cells that are either EGFP-immunoreactive or PPTB-immunoreactive are present in this field, but none of them is double-labelled. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Neurotensin immunoreactivity was less dense than that seen for SST and showed a different laminar distribution, being concentrated in lamina IIi where it overlapped the dense plexus of PKCγ dendrites (Figure 2). Again, cell bodies were difficult to identify at low magnification but could readily be seen with oil-immersion optics. Staining of cell bodies appeared as intense granules that occupied part of the perikaryal cytoplasm (Figures 2 and 4) and, in some cases, completely surrounded the nucleus (Figure 6a). Neurotensin-immunoreactive cells were concentrated in the inner half of lamina II and the dorsal part of lamina III. They accounted for 7% of all neurons in laminae I–II and 8% of those in lamina III (Table 2). The great majority of these cells (90%) were PKCγ-immunoreactive, and these accounted for 34% of the PKCγ cells in laminae I–III (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Neurotensin and PPTB immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining with antibodies against neurotensin (NT, green), PPTB (red), and NeuN (blue) in a single optical section at the lamina II/III border. (d) A merged image. Two neurotensin–immunoreactive cells (arrows) and two PPTB-immunoreactive cells (arrowheads) are indicated. In each case, the cells are negative for the other marker. Scale bar = 10 µm.

As in the rat,35 the pattern of staining with the PPTB antibody differed from that seen with the SST and neurotensin antibodies, in that it was particularly prominent in cell bodies, which could be seen at low magnification (Figure 3a), and this is presumably because the antibody is directed against the precursor peptide rather than the mature neuropeptide.48 NKB-expressing (PPTB-immunoreactive) cells were also concentrated in the inner half of lamina II, with some extension into lamina III. Unlike what has been reported in the rat,35 we saw very few PPTB-immunoreactive neurons in laminae I or IIo. PPTB+ cells accounted for 12% of all neurons in laminae I–II, and 4% of those in lamina III. The majority (58%) of the PPTB cells were PKCγ-immunoreactive, and these accounted for 28% of the PKCγ cells. However, as in the rat,35 the intensity of PKCγ immunoreactivity seen on these PPTB cells was generally weak or moderate (Figure 3d–g).

As reported previously,36,44 GRP-EGFP cells were mainly restricted to lamina II, and they accounted for 11% of the neurons in laminae I–II. Although scattered GRP-EGFP cells are present in lamina III, we did not quantify these.

Coexistence among neuropeptide populations

In sections reacted to reveal SST and the three other peptide populations (neurotensin, PPTB, GRP-EGFP), we found extensive co-localisation of SST with each of the other markers (Figures 4 and 5, Table 4). In laminae I–II, the majority (73%) of neurotensin-immunoreactive cells were SST-immunoreactive (corresponding to 10% of the SST-immunoreactive cells), although co-localisation was much less common in lamina III, with only 10% of neurotensin cells showing SST immunoreactivity (corresponding to 3% of SST cells) (Figure 4, Table 4). A majority (59%) of GRP-EGFP+ cells in laminae I–II in these sections were also SST-immunoreactive (corresponding to 15% of the SST population). However, there was minimal overlap between neurotensin and GRP-EGFP in these sections, with only 1.5% of GRP-EGFP cells in laminae I–II showing neurotensin immunoreactivity, and 1.7% of neurotensin-immunoreactive cells having EGFP. Most of the PPTB-immunoreactive cells in laminae I–II (91%) showed SST immunoreactivity, corresponding to 21% of the SST cells, although coexistence was less common in lamina III, where 55% of PPTB+ cells were SST-immunoreactive, corresponding to 25% of the SST population (Figure 5, Table 4).

Figure 5.

SST and PPTB immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining with antibodies against PPTB (red), SST (green), and NeuN (blue) in a maximum intensity projection of three optical sections (1 µm z-spacing) from the lamina II/III border. (d) A merged image. Five PPTB-immunoreactive cells are indicated. Four of these are also SST-immunoreactive (arrows), while the fifth (arrowhead) lacks SST. Two neurons that are SST-immunoreactive but negative for PPTB are marked with asterisks. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Table 4.

Co-localisation of SST with other neuropeptide markers.

| Laminae I–II |

Lamina III |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of SST neurons examined | Total number of other neurons examined | % SST neurons with other marker | % other marker neurons with SST | Total number of SST neurons examined | Total number of other neurons examined | % SST neurons with other marker | % other marker neurons with SST | |

| Neurotensin | 171.7 (131–218) | 56.3 (46–63) | 9.5 (7.8–12.2) | 73.4 (71.4–75) | 30 (24–41) | 20 (17–24) | 3 (0–4.9) | 10.4 (5.3–17.6) |

| GRP-EGFP | 171.7 (131–218) | 107.3 (91–121) | 15.4 (13.3–16.8) | 59 (51.6–65.3) | ||||

| PPTB | 140 (119–156) | 88.3 (83–95) | 20.6 (17.2–24.4) | 90.5 (87.4–92.6) | 22.7 (18–28) | 23.7 (21–27) | 25.4 (16.7–32.1) | 54.5 (47.6–59.3) |

The second and third columns show the total numbers of neurons examined in laminae I–II that were either SST-immunoreactive or immunoreactive for the other marker, respectively. The corresponding values for lamina III are shown in the sixth and seventh columns. Note that, as described in the Methods section a relatively narrow disector (10 µm) was initially used to sample SST-immunoreactive neurons and test the proportion with the other marker. A wider disector (between 18 and 30 µm) was then used to sample neurons with the other type of immunoreactivity and test them for the presence of SST-immunoreactivity. This was done because the number of SST-immunoreactive neurons was far larger than the number of cells immunoreactive for each of the other markers. In each case, the mean values for three mice are shown, with the range in brackets.

In sections reacted to reveal neurotensin and PPTB, we found limited overlap between the two in laminae I–II, with double-labelled cells corresponding to 13% and 6% of the neurotensin and PPTB populations, respectively (Figure 6, Table 5). The extent of co-existence was higher in lamina III, corresponding to 34% and 30% of neurotensin and PPTB cells, respectively.

Table 5.

Co-localisation of neurotensin (NT) with PPTB.

| Laminae I–II |

Lamina III |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total NT neurons counted | Total PPTB neurons counted | % NT neurons with PPTB | % PPTB neurons with NT | Total NT neurons counted | Total PPTB neurons counted | % NT neurons with PPTB | % PPTB neurons with NT |

| 47 (38–52) | 103 (98–109) | 12.6 (10.5–15.7) | 5.7 (4.1–7.3) | 23 (15–27) | 25.3 (24–27) | 33.8 (33.3–34.6) | 30.1 (20.8–36) |

The first and second columns show the total numbers of neurons examined in laminae I–II that were either NT-immunoreactive or PPTB-immunoreactive, while the corresponding values for lamina III are shown in the fifth and sixth columns. In each case, the mean values for three mice are shown, with the range in brackets.

In the sections that were immunostained for PPTB and GRP-EGFP, no co-localisation was detected (Figure 7).

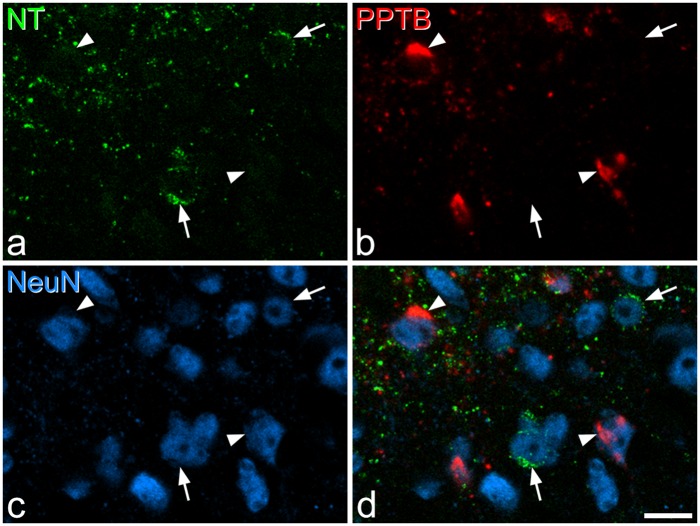

Co-localisation of SST and calretinin

Although both SST and calretinin are expressed by large numbers of excitatory interneurons in the superficial dorsal horn, Duan et al.25 provided evidence to suggest that they were present in non-overlapping populations. However, we found extensive overlap between SST- and calretinin-immunoreactivities in laminae I–II (Figure 8). The mean numbers of SST- and calretinin-immunoreactive cells identified in these sections were 178.3 (175–181) and 137.7 (126–161), respectively. Double-labelled cells accounted for 52.7% (49.2%–55.9%) of the SST-immunoreactive cells and 67% (60.9%–70.6%) of the calretinin-immunoreactive population.

Figure 8.

Calretinin and SST immunoreactivity. (a–c) Immunostaining for calretinin (CR, green) and SST (red) in a single optical section through lamina II. (d) A merged image, which also shows staining for NeuN (blue). Several calretinin-immunoreactive cell bodies are present in the section, and three of these are marked with arrows. Each of these cells show SST-immunoreactivity. The two calretinin-labelled profiles indicated with arrowheads are proximal dendrites of lamina II neurons, and both of these are also SST-immunoreactive. The asterisk marks a SST-immunoreactive neuron that lacks calretinin. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are: (1) that immunoreactivity for SST, neurotensin, and PPTB are present in 44%, 7% and 10% of neurons in laminae I–II, respectively, while 11% of neurons in this region are EGFP+ in the GRP-EGFP mouse and (2) that while the neurotensin, PPTB and GRP-EGFP populations are largely non-overlapping, there is extensive co-localisation of SST with each of these other markers.

Identification of peptidergic cell bodies with immunocytochemistry

Although neuropeptides are synthesised and packaged in the perikaryal cytoplasm of peptidergic neurons, they are then transported to their axons, so that the concentration of neuropeptide in the cell body is often relatively low. For some peptides (e.g. substance P), concentrations in cell bodies are so low that they are undetectable with immunocytochemistry. In many early studies, colchicine was administered to block axoplasmic transport and increase somatic concentrations of peptides,21 but it was subsequently shown that colchicine could alter mRNA levels for neuropeptides and potentially lead to de novo expression.66,67 An alternative approach for identifying peptidergic neurons would be to use in situ hybridisation, but this is less easily combined with the multiple-labelling strategies that are required for quantification and assessment of co-localisation. In the present study, we identified NKB-expressing neurons with an antibody against the precursor peptide (PPTB), which was seen at high levels in cell bodies, with a distribution closely matching that of PPTB mRNA,37,68,69 and it is, therefore, likely that we detected most or all of the NKB-expressing cells. With both neurotensin and SST antibodies, we were able to detect many cells that had immunoreactivity in the perikaryal cytoplasm, and in each case, the distribution of cells closely matched that reported with in situ hybridisation.37,38,70 However, since we may have failed to detect cells with low levels of the peptide in their cell bodies, our results should be considered as minimum estimates. Duan et al.25 reported that the proportions of neurons with SST mRNA in laminae I and II were 7% and 37%, respectively, which is somewhat lower than our estimate that 44% of neurons in laminae I–II were SST-immunoreactive: this discrepancy may reflect greater sensitivity of the immunocytochemical technique or differences in the methods used for counting cells.

Although there are many neurons with GRP mRNA in lamina II,12,28,38,44,46,71,72 antibodies against GRP fail to detect these cells.36 We, therefore, used transgenic mice, in which EGFP is expressed under control of the GRP promoter.36,44,46 Solorzano44 reported that 93% of EGFP cells in this mouse line were positive for GRP mRNA, and that 68% of GRP mRNA-positive cells had EGFP. They also suggested that the failure to detect EGFP in some cells with GRP mRNA may have been due to protease treatment during the in situ hybridisation procedure. It is therefore likely that the great majority (if not all) EGFP+ neurons express GRP, but the use of EGFP as a surrogate marker may have resulted in an underestimate of the size of the GRP population.

Neurochemically defined subpopulations among the excitatory interneurons in laminae I–II

We have reported that all SST-immunoreactive neurons in rat superficial dorsal horn lacked GABA, although some of those in laminae III–IV were GABA and/or glycine enriched.32 We also showed that 98% of non-primary afferent SST-immunoreactive boutons in laminae I–II expressed the vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2.34 Xu et al.37,38 have found that SST mRNA+ cells in the superficial laminae are eliminated in mice lacking the transcription factors Tlx1/3, which are required for the development of excitatory interneurons in this region. Taken together, these results suggest that all SST-expressing neurons in laminae I–II are excitatory, although some of those in deeper laminae are inhibitory. Similarly, in the rat, all neurotensin-immunoreactive cell bodies in laminae II–III lack GABA,31 while neurotensin axons (which are thought to originate from local cells) are glutamate-enriched,33 and 94% of these are VGLUT2-immunoreactive.34 PPTB-immunoreactive axons are also likely to originate from local interneurons, and in the rat, 99% of these were VGLUT2-immunoreactive35 while all cells in laminae II–III of the mouse with PPTB mRNA were immunoreactive for Tlx3.37 Cells with GRP mRNA in lamina II are absent in mice lacking the transcription factors Gsx1/2 or Tlx3, in which development of excitatory cells is disrupted,28,38 while EGFP+ cells in the GRP-EGFP mouse lack Pax2 and have axons that are immunoreactive for VGLUT2, but not for the vesicular GABA transporter.36 Again, this strongly suggests that expression of neurotensin, NKB and GRP is restricted to excitatory neurons in this region.

We have previously reported that neurons lacking GABA- and glycine-immunoreactivity account for 74.2% and 62.4% of the total neuronal population in laminae I–II and lamina III, respectively.73 Since these cells are all likely to be glutamatergic,14 this allows us to estimate the proportions of excitatory neurons in these regions that express SST, neurotensin, PPTB or GRP-EGFP. In laminae I–II, cells belonging to each of these neuropeptide populations should account for 59%, 9%, 13.6% and 14.8% of the glutamatergic neurons, respectively (Table 2). We can also estimate that neurotensin- and PPTB-expressing cells would account for 12.5% and 6.6% of excitatory interneurons in lamina III, respectively. However, since SST+ cells in lamina III include an unknown proportion of inhibitory interneurons,25,32 it is not possible to determine the percentage of excitatory neurons in this lamina that are SST-immunoreactive.

The present findings are generally consistent with what has been reported in the rat, for example, in both species, SST is expressed by numerous cells and overlaps extensively with PPTB+ neurons, while the majority of both neurotensin and PPTB cells express PKCγ.35,43 However, there are some differences, including a limited overlap between neurotensin and PPTB populations and the expression of SST in most neurotensin cells in the mouse, neither of which were seen in the rat.32,35 In addition, there are many PPTB-immunoreactive neurons in lamina I-IIo in the rat,35 and these are not detected in the mouse either with immunocytochemistry or with in situ hybridisation,69,70 which suggests that this is a species difference.

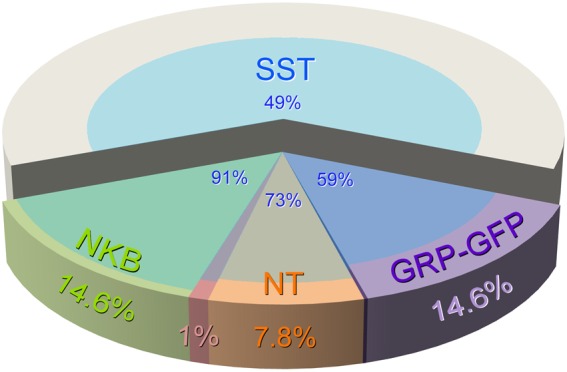

The limited overlap among the neurotensin, PPTB and GRP populations allows us to estimate that between them, they account for ∼37% of the excitatory interneurons in laminae I–II. This is illustrated in Figure 9, which also reveals the extent to which each of these populations (together with excitatory neurons that lack neurotensin, NKB or GRP-EGFP) express SST.

Figure 9.

Proportions of excitatory neurons in laminae I–II that belong to different neurochemical populations. The pie chart shows the proportions of all excitatory interneurons in laminae I–II that are accounted for by each neurochemical population. Note that there is no overlap between GRP-EGFP and NKB-expressing (PPTB-immunoreactive) populations, but a minimal overlap between each of these and the neurotensin population. In contrast, SST is expressed by the majority (59%–91%) of cells in each of the other peptide populations, as well as by many (49%) of those that lack these other peptides.

Cholecystokinin is expressed by neurons in lamina III that are derived from a Tlx3+ population,37 and they are also dependent on Gsx1/2,28 suggesting that these cells are exclusively excitatory interneurons. It will, therefore, be of interest to know whether they overlap with either neurotensin or PPTB populations in this lamina. Substance P-expressing cells can be identified by the presence of Tac1 mRNA, and Xu et al.38 identified a Tlx3-dependent population of these cells in laminae I–II. We have reported that substance P, NKB and EGFP are not co-localised in axonal boutons in the GRP-EGFP mouse,36 and we have also found no co-localisation of neurotensin with substance P in the mouse superficial dorsal horn (MGM and AJT, unpublished observations). This suggests that the substance P-expressing cells correspond to an additional population that does not overlap with those that express neurotensin, NKB or GRP.

Functional roles of neurochemically defined excitatory interneuron populations

Various roles have been attributed to excitatory interneurons in the superficial laminae. Mice lacking PKCγ show reduced neuropathic pain,64 and it has been suggested that the PKCγ-expressing cells in laminae IIi–III provide a route through which tactile inputs can gain access to nociceptive projection neurons in lamina I.45 Our results indicate that both NKB and neurotensin are expressed by PKCγ neurons in this region, accounting for around a quarter and a third of the PKCγ cells, respectively. Duan et al.25 reported that ablation of the NKB population had no effect on nerve-injury induced tactile allodynia. This could be because PKCγ cells that are required for the development of tactile allodynia are those that lack NKB, or alternatively because it is necessary to lose a high proportion of the PKCγ cells before this affects neuropathic pain. A further complication is that there may be a mismatch between cells that are targeted in ablation studies25 and those with detectable levels of the corresponding neuropeptide. For example, this could result from a very low level of peptide expression in some neurons, the presence of cells that fail to translate the corresponding mRNA, and/or incomplete loss of cells that express the toxin-encoding transgene.

The present findings indicate that SST is expressed in the majority of excitatory neurons in the superficial laminae, including most of those belonging to the other peptidergic populations (Figure 9). Consistent with this, Duan et al.25 reported that Cre-expressing cells in a SSTCre knock-in mouse were physiologically and morphologically heterogeneous. SST-expressing excitatory neurons are, therefore, very unlikely to correspond to a single functional population, and the finding that their ablation disrupted mechanical pain is perhaps not surprising, since this is likely to have resulted in loss of a large and diverse set of excitatory interneurons.

However, Duan et al.25 reported that ablating calretinin-expressing cells caused only a loss of sensation of light punctate mechanical stimuli. Based on their failure to detect SST mRNA in Cre+ neurons in a calretininCre knock-in mouse, they concluded that SST and calretinin were present in separate populations in laminae I–II and that SST cells were required for detecting mechanical pain, whereas calretinin neurons mediated light punctate sensation. However, our finding that over half of the SST-immunoreactive cells contained calretinin, and that two thirds of calretinin cells contained SST indicate that the SST and calretinin populations are not mutually exclusive. An alternative explanation for the behavioural differences seen after ablation of SST and calretinin cells is that a significant proportion of the calretinin population consists of inhibitory interneurons. A recent study has shown that 12% of calretinin-immunoreactive cells in laminae I–II of the mouse express Pax2 and are, therefore, presumably inhibitory.42 Further evidence for this was that EGFP-labelled cells in a calretinin-EGFP mouse included typical islet cells, which are invariably inhibitory.14,15,45,74–76 It is, therefore, possible that by ablating calretinin cells, Duan et al.25 lost both excitatory interneurons (which overlap extensively with the SST population) and also a set of GABAergic (inhibitory) islet cells. If the latter have a role in inhibiting mechanical pain, then their loss could have partially compensated for the reduction in excitatory transmission.

Interestingly, Duan et al.25 found that although mechanical pain was dramatically reduced following ablation of the SST cells, thermal pain was unaffected. Mechanical pain perception in the mouse is thought to depend on non-peptidergic unmyelinated primary afferents that express the Mas-related protein Mrgd, whereas thermal pain requires TRPV1+ primary afferents, which largely correspond to those that express neuropeptides.77,78 The C-Mrgd afferents terminate in the middle part of lamina II and do not provide direct synaptic input to nociceptive projection neurons in laminae I or III.79 In contrast, peptidergic nociceptors directly innervate projection neurons in both laminae I and III,80,81 and we have estimated that these afferents provide around half of the excitatory synapses on the neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing lamina I projection cells.82 It is, therefore, likely that much of the thermal nociceptive input reaches projection neurons directly, whereas the noxious mechanical input is relayed through excitatory interneurons in lamina II that constitute part of the SST population.

Conclusions

These results suggest that cells expressing neurotensin, NKB or GRP form largely non-overlapping populations, which account for ∼40% of the excitatory interneurons in laminae I–II, and these populations are, therefore, likely to be functionally distinct. In contrast, SST is expressed by ∼60% of excitatory interneurons in the superficial laminae, and the SST cells are presumably functionally heterogeneous.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr R Kerr and Ms C Watt for excellent technical assistance, to Dr P Ciofi and Prof T Kaneko for the gifts of antibodies, and to Dr E Polgár for help in some experiments. The mouse strain Tg(GRP-EGFP) was originally obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (MMRRC), a National Center for Research Resources- and NIH-funded strain repository, and was donated to the MMRRC by the NINDS-funded GENSAT BAC transgenic project.

Author contributions

M. G. M. and A. J. T. designed the study, performed the anatomical experiments, and analysed the resulting data; T. F. and M. W. generated antibodies used in the study. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant Number 102645).

References

- 1.Braz J, Solorzano C, Wang X, et al. Transmitting pain and itch messages: a contemporary view of the spinal cord circuits that generate gate control. Neuron 2014; 82: 522–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd AJ. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11: 823–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoon MA. Molecular dissection of itch. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2015; 34: 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro-da-Silva A, De Koninck Y. Morphological and neurochemical organization of the spinal dorsal horn. In: Basbaum AI, Bushnell MC. (eds). Science of Pain, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008, pp. 279–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuner R. Central mechanisms of pathological pain. Nat Med 2010; 16: 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross SE. Pain and itch: insights into the neural circuits of aversive somatosensation in health and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2011; 21: 880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraira VE, Ginty DD. The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron 2013; 79: 618–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965; 150: 971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spike RC, Puskar Z, Andrew D, et al. A quantitative and morphological study of projection neurons in lamina I of the rat lumbar spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 2003; 18: 2433–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bice TN, Beal JA. Quantitative and neurogenic analysis of neurons with supraspinal projections in the superficial dorsal horn of the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 1997; 388: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grudt TJ, Perl ER. Correlations between neuronal morphology and electrophysiological features in the rodent superficial dorsal horn. J Physiol 2002; 540: 189–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Zhang J, Eberhart D, et al. Excitatory superficial dorsal horn interneurons are functionally heterogeneous and required for the full behavioral expression of pain and itch. Neuron 2013; 78: 312–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobel S. Golgi studies of the neurons in layer II of the dorsal horn of the medulla (trigeminal nucleus caudalis). J Comp Neurol 1978; 180: 395–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasaka T, Tiong SYX, Hughes DI, et al. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain 2010; 151: 475–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxwell DJ, Belle MD, Cheunsuang O, et al. Morphology of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in superficial laminae of the rat dorsal horn. J Physiol 2007; 584: 521–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, et al. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurones identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol 2004; 560: 249–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Punnakkal P, von Schoultz C, Haenraets K, et al. Morphological, biophysical and synaptic properties of glutamatergic neurons of the mouse spinal dorsal horn. J Physiol 2014; 592: 759–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos SF, Rebelo S, Derkach VA, et al. Excitatory interneurons dominate sensory processing in the spinal substantia gelatinosa of rat. J Physiol 2007; 581: 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider SP. Functional properties and axon terminations of interneurons in laminae III-V of the mammalian spinal dorsal horn in vitro. J Neurophysiol 1992; 68: 1746–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prescott SA, De Koninck Y. Four cell types with distinctive membrane properties and morphologies in lamina I of the spinal dorsal horn of the adult rat. J Physiol 2002; 539: 817–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Todd AJ, Spike RC. The localization of classical transmitters and neuropeptides within neurons in laminae I-III of the mammalian spinal dorsal horn. Prog Neurobiol 1993; 41: 609–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polgar E, Sardella TC, Tiong SY, et al. Functional differences between neurochemically defined populations of inhibitory interneurons in the rat spinal dorsal horn. Pain 2013; 154: 2606–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sardella TC, Polgar E, Garzillo F, et al. Dynorphin is expressed primarily by GABAergic neurons that contain galanin in the rat dorsal horn. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kardon AP, Polgar E, Hachisuka J, et al. Dynorphin acts as a neuromodulator to inhibit itch in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuron 2014; 82: 573–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan B, Cheng L, Bourane S, et al. Identification of spinal circuits transmitting and gating mechanical pain. Cell 2014; 159: 1417–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes DI, Sikander S, Kinnon CM, et al. Morphological, neurochemical and electrophysiological features of parvalbumin-expressing cells: a likely source of axo-axonic inputs in the mouse spinal dorsal horn. J Physiol 2012; 590: 3927–3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganley RP, Iwagaki N, Del Rio P, et al. Inhibitory interneurons that express GFP in the PrP-GFP mouse spinal cord are morphologically heterogeneous, innervated by several classes of primary afferent and include lamina I projection neurons among their postsynaptic targets. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 7626–7642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brohl D, Strehle M, Wende H, et al. A transcriptional network coordinately determines transmitter and peptidergic fate in the dorsal spinal cord. Dev Biol 2008; 322: 381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Perl ER. Modular organization of excitatory circuits between neurons of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (laminae I and II). J Neurosci 2005; 25: 3900–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasaka T, Tiong SY, Polgar E, et al. A putative relay circuit providing low-threshold mechanoreceptive input to lamina I projection neurons via vertical cells in lamina II of the rat dorsal horn. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todd AJ, Russell G, Spike RC. Immunocytochemical evidence that GABA and neurotensin exist in different neurons in laminae II and III of rat spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience 1992; 47: 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proudlock F, Spike RC, Todd AJ. Immunocytochemical study of somatostatin, neurotensin, GABA, and glycine in rat spinal dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol 1993; 327: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Todd AJ, Spike RC, Price RF, et al. Immunocytochemical evidence that neurotensin is present in glutamatergic neurons in the superficial dorsal horn of the rat. J Neurosci 1994; 14: 774–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todd AJ, Hughes DI, Polgar E, et al. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in neurochemically defined axonal populations in the rat spinal cord with emphasis on the dorsal horn. Eur J Neurosci 2003; 17: 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polgár E, Furuta T, Kaneko T, et al. Characterization of neurons that express preprotachykinin B in the dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience 2006; 139: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutierrez-Mecinas M, Watanabe M, Todd AJ. Expression of gastrin-releasing peptide by excitatory interneurons in the mouse superficial dorsal horn. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y, Lopes C, Qian Y, et al. Tlx1 and Tlx3 coordinate specification of dorsal horn pain-modulatory peptidergic neurons. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 4037–4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Y, Lopes C, Wende H, et al. Ontogeny of excitatory spinal neurons processing distinct somatic sensory modalities. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 14738–14748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albuquerque C, Lee CJ, Jackson AC, et al. Subpopulations of GABAergic and non-GABAergic rat dorsal horn neurons express Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. Eur J Neurosci 1999; 11: 2758–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antal M, Polgar E, Chalmers J, et al. Different populations of parvalbumin- and calbindin-D28k-immunoreactive neurons contain GABA and accumulate 3H-D-aspartate in the dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 1991; 314: 114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang J, Chen J, Wang W, et al. Neurochemical properties of enkephalinergic neurons in lumbar spinal dorsal horn revealed by preproenkephalin-green fluorescent protein transgenic mice. J Neurochem 2010; 113: 1555–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith KM, Boyle KA, Madden JF, et al. Functional heterogeneity of calretinin-expressing neurons in the mouse superficial dorsal horn: Implications for spinal pain processing. J Physiol 2015; 593: 4319–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polgár E, Fowler JH, McGill MM, et al. The types of neuron which contain protein kinase C gamma in rat spinal cord. Brain Res 1999; 833: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solorzano C, Villafuerte D, Meda K, et al. Primary afferent and spinal cord expression of gastrin-releasing peptide: message, protein, and antibody concerns. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 648–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu Y, Dong H, Gao Y, et al. A feed-forward spinal cord glycinergic neural circuit gates mechanical allodynia. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 4050–4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mishra SK, Hoon MA. The cells and circuitry for itch responses in mice. Science 2013; 340: 968–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cameron D, Gutierrez-Mecinas M, Gomez-Lima M, et al. The organisation of spinoparabrachial neurons in the mouse. Pain 2015; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kaneko T, Murashima M, Lee T, et al. Characterization of neocortical non-pyramidal neurons expressing preprotachykinins A and B: a double immunofluorescence study in the rat. Neuroscience 1998; 86: 765–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polgár E, Gray S, Riddell JS, et al. Lack of evidence for significant neuronal loss in laminae I-III of the spinal dorsal horn of the rat in the chronic constriction injury model. Pain 2004; 111: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sterio DC. The unbiased estimation of number and sizes of arbitrary particles using the disector. J Microsc 1984; 134: 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polgár E, Sardella TC, Watanabe M, et al. Quantitative study of NPY-expressing GABAergic neurons and axons in rat spinal dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol 2011; 519: 1007–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sardella TC, Polgar E, Watanabe M, et al. A quantitative study of neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression in laminae I-III of the rat spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience 2011; 192: 708–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiong SY, Polgar E, van Kralingen JC, et al. Galanin-immunoreactivity identifies a distinct population of inhibitory interneurons in laminae I-III of the rat spinal cord. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes DI, Scott DT, Todd AJ, et al. Lack of evidence for sprouting of Abeta afferents into the superficial laminas of the spinal cord dorsal horn after nerve section. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 9491–9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molander C, Xu Q, Grant G. The cytoarchitectonic organization of the spinal cord in the rat. I. The lower thoracic and lumbosacral cord. J Comp Neurol 1984; 230: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porteous R, Petersen SL, Yeo SH, et al. Kisspeptin neurons co-express met-enkephalin and galanin in the rostral periventricular region of the female mouse hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol 2011; 519: 3456–3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, et al. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-alpha around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol, and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 4740–4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development 1992; 116: 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim KK, Adelstein RS, Kawamoto S. Identification of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) as Fox-3, a new member of the Fox-1 gene family of splicing factors. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 31052–31061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Todd AJ, Spike RC, Polgar E. A quantitative study of neurons which express neurokinin-1 or somatostatin sst2a receptor in rat spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience 1998; 85: 459–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibson SJ, Polak JM, Bloom SR, et al. The distribution of nine peptides in rat spinal cord with special emphasis on the substantia gelatinosa and on the area around the central canal (lamina X). J Comp Neurol 1981; 201: 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hunt SP, Kelly JS, Emson PC, et al. An immunohistochemical study of neuronal populations containing neuropeptides or gamma-aminobutyrate within the superficial layers of the rat dorsal horn. Neuroscience 1981; 6: 1883–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLeod AL, Krause JE, Ribeiro-Da-Silva A. Immunocytochemical localization of neurokinin B in the rat spinal dorsal horn and its association with substance P and GABA: an electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol 2000; 420: 349–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malmberg AB, Chen C, Tonegawa S, et al. Preserved acute pain and reduced neuropathic pain in mice lacking PKCgamma. Science 1997; 278: 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori M, Kose A, Tsujino T, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of protein kinase C subspecies in the rat spinal cord: light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol 1990; 299: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cortes R, Ceccatelli S, Schalling M, et al. Differential effects of intracerebroventricular colchicine administration on the expression of mRNAs for neuropeptides and neurotransmitter enzymes, with special emphasis on galanin: an in situ hybridization study. Synapse 1990; 6: 369–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rethelyi M, Mohapatra NK, Metz CB, et al. Colchicine enhances mRNAs encoding the precursor of calcitonin gene-related peptide in brainstem motoneurons. Neuroscience 1991; 42: 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Warden MK, Young WS., 3rd Distribution of cells containing mRNAs encoding substance P and neurokinin B in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 1988; 272: 90–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mar L, Yang FC, Ma Q. Genetic marking and characterization of Tac2-expressing neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system. Mol Brain 2012; 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen Spinal Cord Atlas, http://mousespinal.brain-map.org/.

- 71.Fleming MS, Ramos D, Han SB, et al. The majority of dorsal spinal cord gastrin releasing peptide is synthesized locally whereas neuromedin B is highly expressed in pain- and itch-sensing somatosensory neurons. Mol Pain 2012; 8: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li MZ, Wang JS, Jiang DJ, et al. Molecular mapping of developing dorsal horn-enriched genes by microarray and dorsal/ventral subtractive screening. Dev Biol 2006; 292: 555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polgar E, Durrieux C, Hughes DI, et al. A quantitative study of inhibitory interneurons in laminae I-III of the mouse spinal dorsal horn. PLoS One 2013; 8: e78309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Todd AJ, McKenzie J. GABA-immunoreactive neurons in the dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience 1989; 31: 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu Y, Perl ER. A specific inhibitory pathway between substantia gelatinosa neurons receiving direct C-fiber input. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 8752–8758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng J, Lu Y, Perl ER. Inhibitory neurones of the spinal substantia gelatinosa mediate interaction of signals from primary afferents. J Physiol 2010; 588: 2065–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cavanaugh DJ, Lee H, Lo L, et al. Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 9075–9080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zylka MJ, Rice FL, Anderson DJ. Topographically distinct epidermal nociceptive circuits revealed by axonal tracers targeted to Mrgprd. Neuron 2005; 45: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sakamoto H, Spike RC, Todd AJ. Neurons in laminae III and IV of the rat spinal cord with the neurokinin-1 receptor receive few contacts from unmyelinated primary afferents which do not contain substance P. Neuroscience 1999; 94: 903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Naim M, Spike RC, Watt C, et al. Cells in laminae III and IV of the rat spinal cord that possess the neurokinin-1 receptor and have dorsally directed dendrites receive a major synaptic input from tachykinin-containing primary afferents. J Neurosci 1997; 17: 5536–5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Todd AJ, Puskar Z, Spike RC, et al. Projection neurons in lamina I of rat spinal cord with the neurokinin 1 receptor are selectively innervated by substance P-containing afferents and respond to noxious stimulation. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 4103–4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Polgár E, Al Ghamdi KS, Todd AJ. Two populations of neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing projection neurons in lamina I of the rat spinal cord that differ in AMPA receptor subunit composition and density of excitatory synaptic input. Neuroscience 2010; 167: 1192–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]