Abstract

The prognostic and predictive value of KRAS gene mutations in stage III colorectal cancer is controversial because many recent clinical trials have not involved a surgery‐alone arm. Additionally, data on the significance of extended RAS (KRAS/NRAS) mutations in stage III cancer are not available. Hence, we undertook a combined analysis of two phase III randomized trials, in which the usefulness of adjuvant chemotherapy with tegafur–uracil (UFT) was evaluated, as compared with surgery alone. We determined the association of extended RAS and mismatch repair (MMR) status with the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy. Mutations in KRAS exons 2, 3, and 4 and NRAS exons 2 and 3 were detected by direct DNA sequencing. Tumor MMR status was determined by immunohistochemistry. Total RAS mutations were detected in 134/304 (44%) patients. In patients with RAS mutations, a significant benefit was associated with adjuvant UFT in relapse‐free survival (RFS) (hazard ratio = 0.49; P = 0.02) and overall survival (hazard ratio = 0.51; P = 0.03). In contrast, among patients without RAS mutations, there was no difference in RFS or overall survival between the adjuvant UFT group and surgery‐alone group. We detected deficient DNA MMR in 23/304 (8%) patients. The MMR status was neither prognostic nor predictive for adjuvant chemotherapy. An interaction analysis showed that there was better RFS among patients treated with UFT with RAS mutations, but not for those without RAS mutations. Extended RAS (KRAS/NRAS) mutations are proposed as predictive indicators with respect to the efficacy of adjuvant UFT chemotherapy in patients with resected stage III colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Adjuvant chemotherapy, colorectal cancer, mismatch repair, RAS, tegafur–uracil

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of death from cancer in Japan. Surgical resection offers a potential cure for patients with colon cancer; however, some patients with completely resected cancers continue to die of metastatic relapse. In patients with stage III colon cancer, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is the international standard of care for improved survival. The guidelines at North America and Europe recommend 5‐FU and folic acid (LV) or capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin as the first choice for adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer.1, 2, 3 In addition, radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy is recommended as a standard adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer. However, in Japan, clinical trials of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy have focused mainly on oral fluoropyrimidine‐based regimens in both colon and rectal cancers.4, 5, 6 Tegafur–uracil is a combination drug comprising tegafur, a prodrug of 5‐FU, and uracil, an inhibitor of the 5‐FU‐degrading enzyme dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, in a molar ratio of 1:4. The non‐inferiority of UFT/LV to 5‐FU/LV as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colorectal cancer has been verified in several clinical trials.5, 7 Therefore, at present, the UFT/LV regimen (five courses of 6 months of treatment consisting of UFT 300 mg/m2/day for 28 days plus a 7‐day washout) has been widely adopted in Japan as standard adjuvant chemotherapy.

In metastatic colorectal cancer, KRAS mutation in exon 2 is a well‐established biomarker that predicts a lack of benefit from treatment with anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor mAbs.8, 9, 10 Moreover, patients with metastatic colorectal cancer harboring activating mutations in other RAS (KRAS exons 3 and 4 and NRAS exons 2, 3, and 4) genes were not shown to benefit from anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor therapy in past clinical trials.11, 12, 13 However, the prognostic and predictive value of the KRAS mutation in exon 2 in stage III cancer is controversial because many recent clinical trials have not involved a surgery alone arm.14, 15, 16 Additionally, data on the significance of extended RAS (KRAS and NRAS) mutations in stage III cancer were not reported in these studies.

One of the genetic pathways involved in colorectal cancer is dMMR. Deficient DNA MMR attenuates protein expression (MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and MLH1) leading to high‐frequency microsatellite instability. Some reports suggest that dMMR may predict the response to adjuvant fluoropyrimidine‐based chemotherapy.17, 18, 19 In contrast, the other study has shown that MMR status had no predictive value in respect to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colorectal cancer.20

In this report, we undertook a combined analysis of two phase III randomized trials, NSAS‐CC and NSAS‐RC, in which adjuvant UFT chemotherapy was evaluated in the stage III colorectal cancer setting.4, 21 These trials showed that postoperative adjuvant UFT therapy significantly improved RFS and OS in patients with stage III rectal cancer (RFS, HR = 0.66, P = 0.03; OS, HR = 0.60, P = 0.03), but not colon cancer (RFS, HR = 0.89, P = 0.56; OS, HR = 0.82, P = 0.39). In the current study, we determined the association of extended RAS and MMR status with the effectiveness of surgery plus adjuvant UFT chemotherapy, as compared with surgery alone.

Patients and Methods

Study design and treatment

The NSAS‐CC and NSAS‐RC studies were carried out as multicenter phase III randomized trials to examine the usefulness of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT alone in patients with curatively resected stage III colon or rectal cancer, respectively. The study design and eligibility criteria have been reported previously.4, 21 Enrolment of patients in the original trials occurred between October 1996 and April 2001. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT, or no chemotherapy treatment within 6 weeks after surgery. In the UFT group, UFT (tegafur 400 mg/m2/day; Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was given orally, twice daily for 5 days/week for 1 year. When this study was carried out, LV tablets could not be used because they had not been approved in Japan; therefore, UFT alone was used. The stage was classified according to the General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies on Cancer of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus.22 Cancers arising from the rectosigmoid colon were classified as rectal cancer. A diagnosis of recurrence was assessed by abdominal ultrasonography or computed tomography at 4‐month intervals during the first 2 years and at 6‐month intervals thereafter.

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center Hospital (Tokyo, Japan).

KRAS/NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutation analysis

DNA was extracted from formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tumor samples. The mutation status of KRAS exon 2 (at codons 12 and 13), exon 3 (at codon 61), and exon 4 (at codon 146), NRAS exon 2 (at codons 12 and 13) and exon 3 (at codon 61), and PIK3CA exon 9 (at codons 542 and 545) and exon 20 (at codon 1047) was assessed by means of direct sequencing by the PCR method. Detection of BRAF V600E mutation was achieved using high‐resolution melting analysis, which has been described in detail elsewhere.23

Mismatch repair status determination

Tumor MMR status was determined by immunohistochemistry. A dMMR status was defined as the loss of tumor MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, or MLH1 protein expression. A proficient MMR status was defined by normal tumor MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and MLH1 protein expression. Sections (5 μm thick) from paraffin‐embedded tissues were stained using an Autostainer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Staining was carried out using antibodies to MSH2 (clone FE11, 1/200; Calbiochem, Tokyo, Japan), MSH6 (clone EPR3945, 1/200; GeneTex, Hsinchu City, Taiwan), PMS2 (clone A16‐4, 1/200; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Tokyo, Japan) and MLH1 (clone G168‐278, 1/200; BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Mismatch repair protein loss was defined as abnormal (or absent) when nuclear staining of tumor cells was absent in the presence of positive staining in surrounding cells.

Statistical methods

Our primary objective for this analysis was to evaluate the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT, as compared with surgery alone, in relation to the presence (i.e., any KRAS exon 2, 3, or 4, or NRAS exon 2 or 3 mutations) or absence (i.e., neither KRAS nor NRAS mutation) of RAS mutation in tumor tissues from patients participating in NSAS‐CC/NSAS‐RC trials. Relapse‐free survival was defined as the time from the date of surgery to recurrence or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to death from any cause or last follow‐up. Hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. A multivariate analysis adjusted for tumor stage, primary tumor location, and treatment was carried out. An interaction analysis was used to compare the treatment effect of UFT between subgroups with non‐mutated RAS and RAS mutations, which was adjusted for tumor stage, primary tumor location, MMR status, and treatment.

Between‐group differences in patient characteristics were assessed with the use of the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test of association for categorical variables. Survival curves for RFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were evaluated with the log–rank test. All P‐values are two‐sided. P‐values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance, and 95% CI were calculated. All statistical analyses were carried out with the use of SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

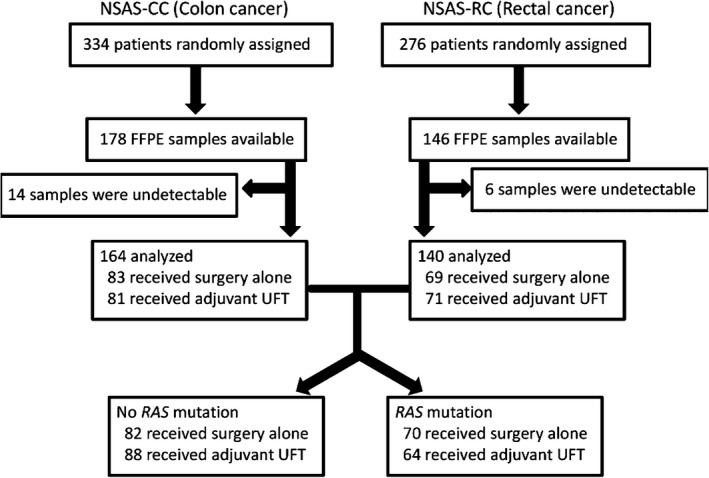

Of the 610 patients (334 with colon cancer and 276 with rectal cancer) who underwent randomization in the original NSAS‐CC/RC trials, we collected 324 tumor samples (178 colon and 146 rectum; Fig. 1). During a median follow‐up of 74.8 months (range, 8.8–176.3 months), there were 115 RFS events and 90 deaths. The status of RAS and MMR was determined in 304 (94%) out of the 324 patients. Of the 304 patients, 134 (44%) were identified as having tumors with mutated RAS (any mutations in exons 2, 3, or 4 of KRAS, or in exons 2 or 3 of NRAS), and 170 (56%) had non‐mutated RAS (no KRAS and NRAS mutations). KRAS exon 2 mutations were detected in 39% of tumors, with 29% detected in codon 12 and 10% in codon 13. The following additional mutation rates were also observed: 0% for KRAS exon 3; 2% for KRAS exon 4; 5% for NRAS exon 2; and 2% for NRAS exon 3 (Table S1). Mutations of both KRAS and NRAS occurred in eight patients; specifically, mutations in KRAS exon 2 and NRAS exon 2 (n = 7), along with KRAS exon 2 and NRAS exon 3 (n = 1). Overall, RAS mutations were detected in 82/152 (54%) of the surgery alone group and in 88/152 (58%) of the adjuvant UFT group. Seven cases (4%) displayed a BRAF exon 15 (V600E) mutation in those patients without RAS mutations who could be evaluated for BRAF status. Mutations in BRAF exon 15 were mutually exclusive of KRAS and NRAS mutations. PIK3CA mutations were detected in 14% of tumors, with 10% detected in exon 9 and 4% in exon 20. Table 1 summarizes the baseline clinicopathologic characteristics of patients according to RAS mutation status. There was no difference according to gender, age, primary tumor location, histopathologic grade, T stage, N stage, tumor stage, treatment (surgery alone or adjuvant UFT), or MMR status between the non‐mutated and RAS mutated groups. Deficient DNA MMR was detected in 14/170 (8%) of the non‐mutated group and 9/134 (7%) of the RAS mutated group. Among dMMR tumors, those showing loss of MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and MLH1 protein expression were 9, 4, 7, and 11, respectively (multiple protein loss was observed in some tumors).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Colon Cancer (NSAS‐CC) and National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Rectal Cancer (NSAS‐RC) trials evaluating the impact of RAS mutations. UFT, tegafur–uracil.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics in patients with stage III colorectal cancer according to RAS mutation (n = 304)

| Variable, n (%) | No RAS mutation | RAS mutation | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 170) | (n = 134) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 99 (58) | 69 (51) | 0.24 |

| Female | 71 (42) | 65 (49) | |

| Age, year | |||

| Median (range) | 61 (36–74) | 59 (32–75) | 0.28 |

| Primary tumor location | |||

| Colon | 92 (54) | 72 (54) | 0.94 |

| Rectum | 78 (46) | 62 (46) | |

| Histopathologic grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 37 (22) | 36 (27) | 0.22 |

| Moderately differentiated | 120 (71) | 90 (67) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 (6) | 3 (2) | |

| Mucinous | 3 (1) | 5 (4) | |

| T stage | |||

| T1–3 | 113 (66) | 86 (64) | 0.67 |

| T4 | 57 (34) | 48 (36) | |

| N stage | |||

| N1 | 135 (79) | 112 (84) | 0.52 |

| N2 | 26 (15) | 18 (13) | |

| N3 | 9 (6) | 4 (3) | |

| Tumor stage | |||

| IIIa | 135 (79) | 111 (83) | 0.45 |

| IIIb | 35 (21) | 23 (17) | |

| Treatment | |||

| Surgery alone | 82 (48) | 70 (52) | 0.48 |

| Adjuvant UFT | 88 (52) | 64 (48) | |

| MMR | |||

| pMMR | 156 (92) | 125 (93) | 0.63 |

| dMMR | 14 (8) | 9 (7) | |

dMMR, deficient DNA mismatch repair; MMR, mismatch repair; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair; UFT, tegafur–uracil.

Prognostic value of RAS and MMR status on efficacy of surgery alone

Among patients treated with surgery alone, there was no significant difference in RFS or OS between patients without and with RAS mutations (5‐year RFS, 64.6% and 61.4%, respectively; HR = 1.23; 95% CI, 0.73–2.06; P = 0.43; 5‐year OS, 77.3% and 70.0%, respectively; HR = 1.46; 95% CI, 0.82–2.59; P = 0.19). Mismatch repair status also had no impact on RFS (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.27–2.07; P = 0.58) or OS (HR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.33–2.58; P = 0.89). Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model revealed that both RAS and MMR statuses were not prognostic factors (Table S2).

Predictive value of RAS and MMR status on efficacy of adjuvant UFT

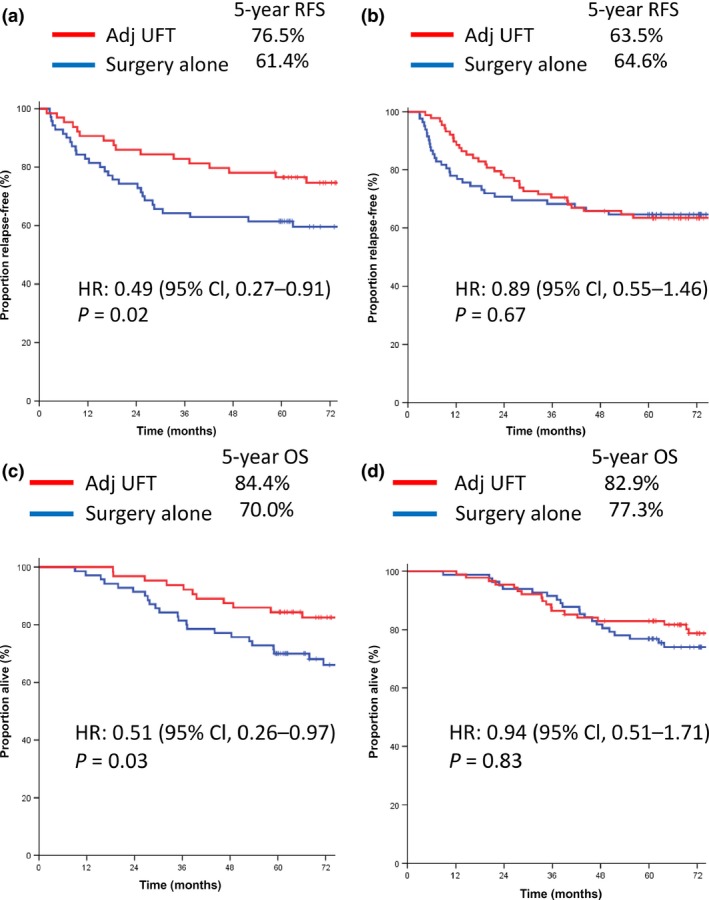

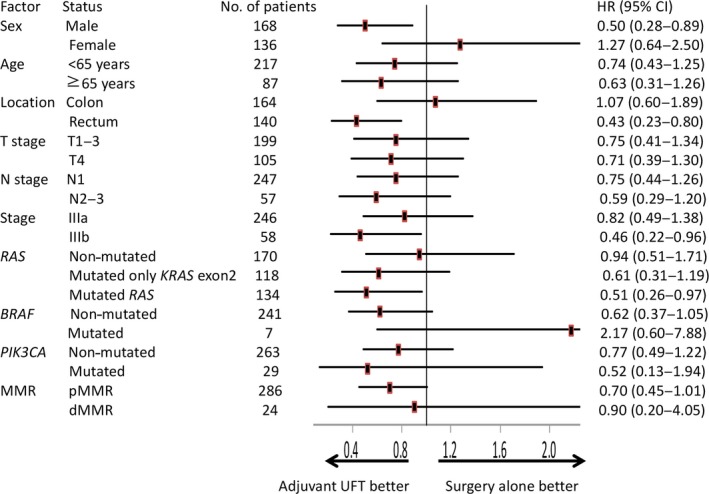

As shown in Figure 2, when comparing patients with extended RAS mutation who received adjuvant UFT to those who received surgery alone, there were significant improvements in RFS (5‐year RFS, 76.5% and 61.4%, respectively; HR = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.27–0.91; P = 0.02; Fig. 2a) and OS (5‐year OS, 84.4% and 70.0%, respectively; HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.26–0.97; P = 0.03; Fig. 2c). In contrast, among patients without RAS mutation, there was no significant difference in RFS (5‐year RFS, 63.5% and 64.6%, respectively; HR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.55–1.46; P = 0.67; Fig. 2b) or OS (5‐year OS, 82.9% and 77.3%, respectively; HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.51–1.71; P = 0.83; Fig. 2d) between the adjuvant UFT chemotherapy plus surgery and surgery alone groups. There was a trend toward improved survival among patients with only KRAS exon 2 mutations treated with UFT as compared to those managed by surgery alone, but the difference was not statistically significant (RFS, HR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.30–1.07; P = 0.07; OS, HR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.31–1.19; P = 0.14). There was no statistical significance in RFS or OS between the adjuvant UFT and surgery‐alone group for patients with dMMR tumors (RFS, HR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.26–4.20; P = 0.95; OS, HR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.20–4.05; P = 0.89) or proficient MMR tumors (RFS, HR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.44–1.02; P = 0.06; OS, HR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.45–1.01; P = 0.11). In addition, among patients with BRAF or PIK3CA mutations, there was no statistically significant difference in OS between the adjuvant UFT group and the surgery‐alone group. The benefit of adjuvant UFT in relation to OS is shown in Figure 3. The use of adjuvant UFT was associated with significantly better survival for patients in subgroups with male gender, rectal cancer, stage IIIb disease, and any evidence of RAS mutation.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse‐free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in colorectal cancer patients, according to treatment group. (a,b) RFS in patients with extended RAS mutation (a) and with no RAS mutation (b). (c,d) OS in patients with extended RAS mutation (c), and with no RAS mutation (d). Adj, adjuvant; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; UFT, tegafur–uracil.

Figure 3.

Forest plots of hazard ratios for overall survival time in selected colorectal cancer patient groups. dMMR, deficient DNA mismatch repair; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair; UFT, tegafur–uracil.

Predictive value of RAS status according to primary tumor location

With regard to the primary tumor location, adjuvant UFT was associated with a significant benefit in rectal cancer patients with RAS mutations in terms of both RFS (5‐year RFS, 76.7% and 50.0%, respectively; HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.15–0.89; P = 0.02) and OS (5‐year OS, 86.7% and 62.5%, respectively; HR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.09–0.80; P = 0.01), although the difference was not statistically significant in relation to colon cancer patients (5‐year RFS, 73.5% and 71.1%; HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.33–1.68; P = 0.49; 5‐year OS, 82.4% and 76.3%; HR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.33–1.91; P = 0.61, respectively; Table 2). In colon cancer patients without RAS mutations, there was a trend toward shorter survival in the adjuvant UFT group compared to the surgery alone group. However, in the case of the adjuvant UFT group, the HR of recurrence or death in those patients with RAS mutations as opposed to patients without RAS mutations was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.30–1.41) in colon cancer patients, and 0.65 (95% CI, 0.26–1.63) in rectal cancer patients. Therefore, the effects of UFT on patients, either with or without RAS mutation, were similar for both colon and rectal cancer.

Table 2.

Treatment efficacy results according to RAS mutation status in patients with stage III colorectal cancer

| Parameter | No RAS mutation (all) | RAS mutation (all) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery alone | UFT | Surgery alone | UFT | |

| (n = 82) | (n = 88) | (n = 70) | (n = 64) | |

| 5‐year RFS, % | 64.6 | 63.5 | 61.4 | 76.5 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.89 (0.55–1.46) | 0.49 (0.27–0.91) | ||

| P‐value | 0.67 | 0.02 | ||

| 5‐year OS, % | 77.3 | 82.9 | 70.0 | 84.4 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.51–1.71) | 0.51 (0.26–0.97) | ||

| P‐value | 0.83 | 0.03 | ||

| Parameter | No RAS mutation (colon) | RAS mutation (colon) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery alone | UFT | Surgery alone | UFT | |

| (n = 45) | (n = 47) | (n = 38) | (n = 34) | |

| 5‐year RFS, % | 71.1 | 59.5 | 71.1 | 73.5 |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.35 (0.66–2.73) | 0.75 (0.33–1.68) | ||

| P‐value | 0.40 | 0.49 | ||

| 5‐year OS, % | 77.8 | 74.5 | 76.3 | 82.4 |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.44 (0.66–3.15) | 0.8 (0.33–1.91) | ||

| P‐value | 0.34 | 0.61 | ||

| Parameter | No RAS mutation (rectum) | RAS mutation (rectum) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery alone | UFT | Surgery alone | UFT | |

| (n = 37) | (n = 41) | (n = 32) | (n = 30) | |

| 5‐year RFS, % | 56.8 | 68.0 | 50.0 | 76.7 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.55 (0.27–1.12) | 0.36 (0.15–0.89) | ||

| P‐value | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||

| 5‐year OS, % | 75.7 | 92.6 | 62.5 | 86.7 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.48 (0.20–1.13) | 0.28 (0.09–0.80) | ||

| P‐value | 0.08 | 0.01 | ||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse free survival.

Interaction analysis showed that, regarding primary tumor location, tumor stage, and MMR status, RFS was better among patients with RAS mutations treated with UFT (HR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.33–1.08; P = 0.09), but not in patients with non‐mutated RAS (HR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.49–1.31; P = 0.37; Table S3).

Discussion

In this report, we undertook a combined analysis of two phase III randomized trials and determined the association of extended RAS (KRAS/NRAS) and MMR status with the effectiveness of surgery plus adjuvant UFT chemotherapy, compared with surgery alone, in stage III colorectal cancer patients. In our patient group, we observed that KRAS/NRAS mutations were significantly associated with the benefit of adjuvant UFT chemotherapy. However, in those patients with tumors containing only KRAS exon 2 mutations, the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, among patients with non‐mutated KRAS/NRAS, there was no significant difference in RFS and OS between the surgery‐alone and adjuvant UFT groups. To our knowledge, we are the first group to show that extended RAS mutations, not only those in KRAS exon 2, affect survival in stage III colorectal cancer patients treated with adjuvant fluoropyrimidine‐based chemotherapy in comparison with no chemotherapy.

In the Quick and Simple and Reliable (QUASAR) trial, in which postoperative colorectal cancer patients were assigned to either adjuvant 5‐FU/LV chemotherapy or no chemotherapy, the risk of recurrence was significantly higher for KRAS mutant compared to KRAS wild‐type tumors.24 However, 91% of patients in that trial had stage II disease, and OS was not evaluated. Additionally, the Kirsten Ras in Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group (RASCAL) study reported an increased risk of recurrence and death linked to KRAS mutations.25 However, this study was based on a large collection of patients enrolled in different studies from various countries. Our data are based on the analysis of a homogenous, prospective cohort that was treated and followed according to the highest clinical standards.

We observed that MMR status was neither prognostic nor predictive for adjuvant chemotherapy. This result differed from other studies reporting that dMMR predicts response to adjuvant fluoropyrimidine‐based chemotherapy.17, 18, 19 Eight percent of tumors were dMMR in our study, which is less than that observed in previous reports, (11–14%).17, 19, 26 The reason may relate to differences in primary tumor location. Hutchins et al. showed that 26% of right‐sided colon, 3% of left‐sided colon, and 1% of rectal tumors were dMMR.24 In our study, nearly half (47%) of all tumors consisted of rectal cancer. Overall, the small number of dMMR tumors in this study may have reduced the power to detect prognostic and predictive value in respect to MMR status.

With regard to primary tumor location, adjuvant UFT was associated with a significant improvement in rectal cancer, but not colon cancer. We hypothesize that the benefit of adjuvant UFT was small for colon cancer patients because the outcome of surgery alone is better in colon cancer than rectal cancer. However, the HR of recurrence or death in patients with RAS mutations, as opposed to patients without RAS mutations, was equal in both colon and rectal cancer patients (both 0.65). Hence, adjuvant UFT chemotherapy improved survival in colon cancer patients, as well as in rectal cancer patients, if RAS mutations were present in tumors.

Today, the standard of care at most centers is fluorouracil or capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX or CapeOX regimen) for all patients with stage III disease. However, some patients are harmed due to toxicity resulting from oxaliplatin treatment, with persistent neuropathy sometimes taking place.27 Our study showed the potential that patients without RAS mutations may not need any adjuvant chemotherapy. Although it may not be realistic to undertake a new surgery‐alone trial in the future, it is a welcome change for many patients if the non‐inferiority of surgery alone relative to surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy is shown in patients without RAS mutations in clinical trials.

An explanation why RAS mutations are associated with the effectiveness of UFT is unknown. However, Maus et al. showed that mutant KRAS status was associated with a lower expression of TS, an enzyme related to 5‐FU sensitivity.28 Inhibition of TS is considered to be the main mechanism for the activity of 5‐FU. Laboratory studies have shown that acquired resistance to 5‐FU has been associated with increased TS expression.29, 30 Therefore, RAS mutations may affect the metabolic pathway of fluoropyrimidines.

In conclusion, KRAS/NRAS mutations are predictive indicators, with respect to the efficacy of adjuvant UFT chemotherapy, in patients with resected stage III colorectal cancer. Further validations of these findings and elucidation of the underlying mechanisms are warranted in future.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- 5‐FU

5‐fluorouracil

- CI

confidence interval

- dMMR

deficient DNA mismatch repair

- HR

hazard ratio

- LV

leucovorin

- MLH1

MutL homolog 1

- MMR

mismatch repair

- MSH

MutS homolog

- NSAS‐CC

National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Colon Cancer

- NSAS‐RC

National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Rectal Cancer

- OS

overall survival

- PMS2

PMS1 homolog 2, mismatch repair system component

- RFS

relapse‐free survival

- TS

thymidylate synthase

- UFT

tegafur–uracil

Supporting information

Table S1. KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutation status in patients with stage III colorectal cancer.

Table S2. Multivariate analysis for relapse‐free survival in patients with stage III colorectal cancer treated with surgery alone.

Table S3. Relapse‐free survival in patients with stage III colorectal cancer: interaction with RAS mutation and treatment arm.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participating patients and their families. We thank H. Morita for her technical assistance. We thank all NSAS‐CC/RC study investigators.

Cancer Sci 107 (2016) 1006–1012

Funding Information

No sources of funding were declared in this study.

References

- 1. André T, Boni C, Navarro M et al Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J et al Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folnic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD et al Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Ann Oncol 2013; 24 (Suppl 6): vi64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamaguchi T, Shirao K, Moriya Y et al Final results of randomized trials by the National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Colorectal Cancer (NSAS‐CC). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011; 67: 587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shimada Y, Hamaguchi T, Mizusawa J et al Randomised phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin versus intravenous fluorouracil and levofolinate in patients with stage III colorectal cancer who have undergone Japanese D2/D3 lymph node dissection: final results of JCOG0205. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 2231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshida M, Ishiguro M, Ikejiri K et al S‐1 as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: a randomized phase III study (ACTS‐CC trial). Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1743–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lembersky BC, Wieand HS, Petrelli NJ et al Oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin compared with intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin in stage II and III carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol C‐06. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M et al Wild‐type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1626–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J et al Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first‐line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A et al Randomized phase III study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) compared with FOLFIRI alone as second‐line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4706–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S et al Panitumumab‐FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1023–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bokemeyer C, Köhne CH, Ciardiello F et al Treatment outcome according to tumor RAS mutation status in OPUS study patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) randomized to FOLFOX4 with/without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32 (Suppl):3505. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Köhne CH et al Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M et al Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC‐3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60‐00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taieb J, Tabernero J, Mini E et al Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab in patients with resected stage III colon cancer (PETACC‐8): an open‐label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 862–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoon HH, Tougeron D, Shi Q et al KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in relation to disease‐free survival in BRAF‐wild‐type stage III colon cancers from an adjuvant chemotherapy trial (N0147 alliance). Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 3033–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Des Guetz G, Schischmanoff O, Nicolas P et al Does microsatellite instability predict the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer? A systematic review with meta‐analysis. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 1890–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G et al Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil‐based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaanan A, Fléjou JF, Emile JF et al Defective mismatch repair status as a prognostic biomarker of disease‐free survival in stage III colon cancer patients treated with adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 7470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li P, Fang YJ, Li F et al ERCC1, defective mismatch repair status as predictive biomarkers of survival for stage III colon cancer patients receiving oxaliplatin‐based adjuvant chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 1238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akasu T, Moriya Y, Ohashi Y et al Adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil‐tegafur for pathological stage III rectal cancer after mesorectal excision with selective lateral pelvic lymphadenectomy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2006; 36: 237–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (ed). General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies on Cancer of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pichler M, Balic M, Stadelmeyer E et al Evaluation of high‐resolution melting analysis as a diagnostic tool to detect the BRAF V600E mutation in colorectal tumors. J Mol Diagn 2009; 11: 140–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K et al Value or mismatic repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D et al Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the multicenter “RASCAL” study. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sinicrope FA, Mahoney MR, Smyrk TC et al Prognostic impact of deficient DNA mismatch repair in patients with stage III colon cancer from a randomized trial of FOLFOX‐based adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V et al Chemotherapy‐induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2‐ to 11‐year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population‐based PROFILES registry. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maus MK, Hanna DL, Stephens CL et al Distinct gene expression profiles of proximal and distal colorectal cancer: implications for cytotoxic and targeted therapy. Pharmacogenomics J 2015; 10: 354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenh CH, Geyer PK, Baskin F et al Thymidylate synthase gene amplification in fluorodeoxyuridine‐resistant mouse cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 1985; 28: 80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters GJ, Backus HH, Freemantle S et al Induction of thymidylate synthase as a 5‐fluorouracil resistance mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002; 1587: 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutation status in patients with stage III colorectal cancer.

Table S2. Multivariate analysis for relapse‐free survival in patients with stage III colorectal cancer treated with surgery alone.

Table S3. Relapse‐free survival in patients with stage III colorectal cancer: interaction with RAS mutation and treatment arm.