Abstract

Background:

Approximately 25% of patients with ulcerative colitis [UC] experience a severe flare requiring steroid therapy to avoid colectomy. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of tacrolimus as a rescue therapy for active UC.

Methods:

Electronic databases were searched for relevant studies assessing the efficacy of tacrolimus for active UC. Outcomes included short- and long-term clinical response, colectomy free rates, and rate of adverse events in randomised controlled trials [RCTs] and observational studies.

Results:

Two RCTs comparing high trough concentration [10–15ng/ml] versus placebo [n = 103] and 23 observational studies [n = 831] were identified. Clinical response at 2 weeks was significantly higher with tacrolimus compared with placebo (risk ratio [RR] = 4.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.09–10.17, p = 0.15 x 10-3] among RCTs. Rates of clinical response at 1 and 3 months were 0.73 [95% CI = 0.64–0.81] and 0.76 [95% CI = 0.59–0.87], and colectomy-free rates remained high at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months [0.86, 0.84, 0.78, and 0.69, respectively] among observational studies. Among RCTs, adverse events were more frequent compared with placebo [RR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.20–3.37, p = 0.83 x 10-2], but there was no difference in severe adverse events [RR = 3.15, 95% CI = 0.14–72.9, p = 0.47]. Severe adverse events were rare among observational studies [0.11, 95% CI = 0.06–0.20].

Conclusions:

In the present meta-analysis, tacrolimus was associated with high clinical response and colectomy-free rates without increased risk of severe adverse events for active UC.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, tacrolimus, immunosuppressant, systematic review, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis [UC] is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that affects the colorectum.1 Traditional therapies for UC include 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants. Advances in understanding the immunological pathways have led to the development of biologicals, which are now widely used for induction and maintenance of remission.2,3 Approximately 25% of patients with UC experience a severe flare during their disease course, requiring hospitalisation and high-dose corticosteroid therapy.4 Furthermore, 30% of UC patients with a severe attack may undergo colectomy due to steroid-refractory disease.5 In patients with severe steroid-refractory UC, intravenous ciclosporine, infliximab, or colectomy are potential therapeutic options.6,7 Tacrolimus, a calcinurin inhibitor with a more potent inhibitory effect on activated T cells compared with ciclosporine, has been increasingly used for the treatment of severe and steroid-refractory UC.8,9

Despite the undoubted efficacy of tacrolimus in inducing remission in UC, the number of studies assessing its efficacy and safety in UC are still limited. Randomised controlled trials [RCTs] performed by Ogata et al. have reported the efficacy of tacrolimus in inducing remission in steroid-refractory UC patients.10,11 Several guidelines now recommend the use of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory active UC.12,13

Ciclosporine has shown beneficial short-term response in severe steroid-refractory UC patients in small RCTs14; however, nearly half of the patients underwent colectomy after a year despite the addition of thiopurines as a maintenance therapy.6,15 The long-term outcome of UC patients treated with tacrolimus remains largely unknown. Treatment with tacrolimus in transplant patients is associated with risks of kidney injury and infections,16 and whether the same applies to patients with UC who are commonly treated for a limited duration also remains unknown.

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to assess the short- and long-term effect as well as the safety of tacrolimus as a rescue therapy in patients with acute UC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data sources

We searched MEDLINE [1993–May 2015], Google scholar [1993–2015], and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [May 2015] for studies assessing the efficacy of tacrolimus in severe and steroid-refractory UC. We also searched abstracts from bibliographies of identified articles for additional references.

2.2. Search strategy and study selection

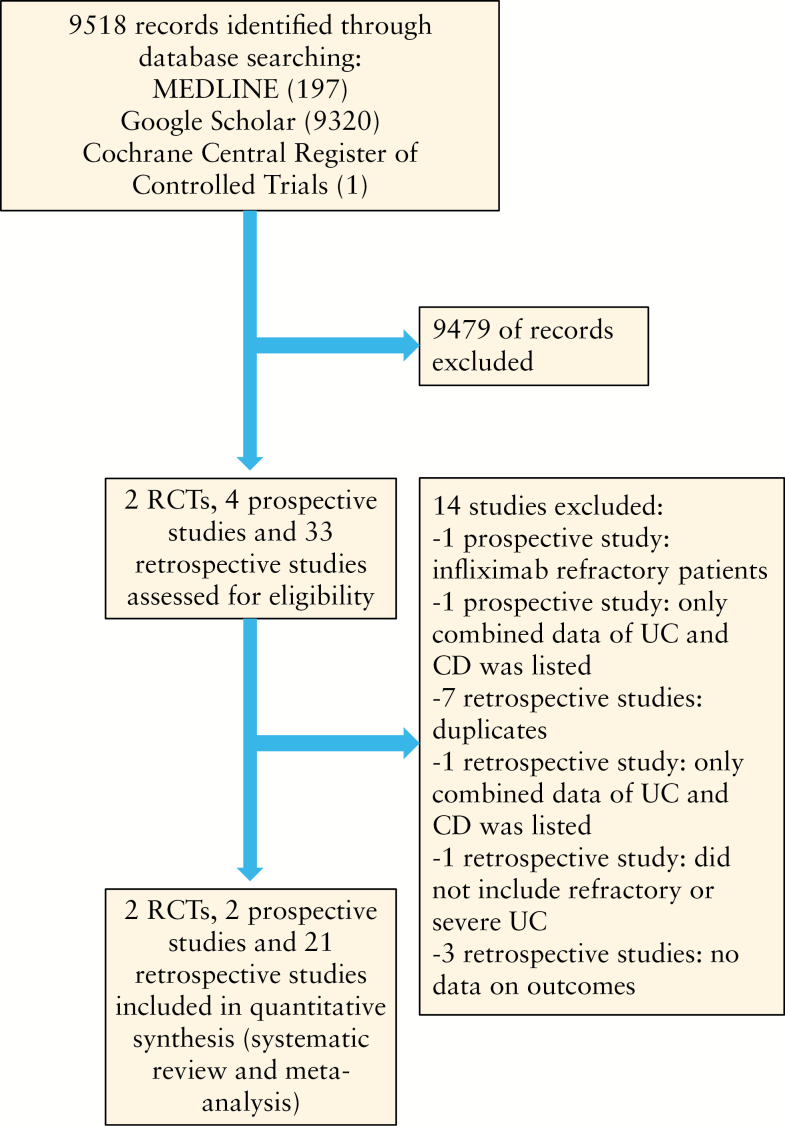

To be eligible for inclusion, we considered RCTs and observational studies evaluating the efficacy of tacrolimus for UC that assessed clinical remission and/or response. There were no restrictions regarding age, sex, and duration of the study. We imposed no geographical or language restrictions and articles in languages other than English, Japanese or German were translated if necessary. Two authors [YK and FK] independently screened each of the potential titles, abstracts, and/or full-manuscripts to determine whether they were eligible for inclusion. Areas of disagreement or uncertainty were resolved by consensus between the authors. The corresponding authors of studies were contacted to provide additional information on trials if required. The following terms were used in the search procedure: ‘tacrolimus’, ‘ulcerative colitis’, ‘therapy’, ‘treatment’, ‘randomized control trial’, ‘prospective study’, ‘retrospective study’, [both as medical subject headings and free-text terms]. These were combined by using the set operator. Search strategy is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of assessment of studies identified in the meta-analysis.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

All data were independently abstracted in duplicate by two authors [YK and FK] by using a data abstraction form. Data on the study characteristics, such as author name, year of publication, country, sample size, age of patients, type of medication used, outcome, and incidence of adverse effects, were collected. Studies that reported events on neither treated nor control groups were excluded from analysis. The Jadad score, a scale that assesses the methodological quality of a clinical trial, was used to assess the quality of RCTs.17

2.4. Outcome assessment

The primary outcome measure of interest was the number of patients achieving clinical response [CR]. Additionally, colectomy-free survival rates at different time points and the rate of adverse reactions were assessed. Analyses were done separately for RCTs and observational studies. Data of intention-to-treat analysis were used except where indicated.

The secondary outcomes were the incidence of overall adverse events in RCTs and the incidence of severe adverse events in both RCTs and observational studies during the treatment of tacrolimus. Analyses were done separately for RCTs and observational studies. Overall adverse event incidence was calculated based on the adverse events reported in each RCT. In regard to severe adverse events, we defined them as those which were specified as such in the study or adverse events which led to discontinuation or reduction of tacrolimus therapy.

Subgroup analysis was performed among the studies that reported the trough concentration of tacrolimus. High trough was defined as > 10ng/ml and low trough was defined as < 10ng/ml.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Random-effects meta-analysis was performed to compare the efficacy between the pair of therapies, where applicable. We also evaluated the presence of heterogeneity across trials by using the I2 statistic, which quantifies the percentage of variability that can be attributed to between-study differences. To assess the potential for publication bias, we performed Begg’s and Egger’s tests and constructed funnel plots to visualise possible asymmetry when three or more studies were available.18,19 For observational studies, data were pooled and shown as forest plots. All statistical analyses were performed with Comprehensive Meta Analysis V2 [Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA]. We followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions in the report of this meta-analysis.20

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

We identified 9518 citations through literature search, excluded 9494 titles and abstracts after initial screening, and assessed 25 full-text articles for eligibility [Figure 1]. We ultimately included two RCTs which assessed the efficacy of tacrolimus compared with placebo in steroid-refractory UC. We identified 23 observational studies reporting the effect of tacrolimus; of these, 21 studies were retrospective cohort studies and 2 were prospective cohorts. A total of 103 patients were included in the analysis of RCTs and 831 patients for the observational studies.

The characteristics and outcomes of the included studies8,10,11,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The two RCTs were conducted among adult patients with moderately-severely active steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent UC. In both studies, the study duration was 2 weeks followed by an open-label 10-week extension in which all patients received tacrolimus. The quality of the studies assessed by the Jadad score showed a median of 4.5 [range 4–5], and both trials were rated to be of good methodological quality.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials of tacrolimus in active UC.

| Study, year, [reference] | Age | Dosage and schedule of therapy | Control group | Study duration | ITT/PP | Jadad score | Definition of clinical response | Definition of clinical remission | Patients [n] | Steroid-resistant/dependent | Clinical response at 2 weeks [n] | Clinical remission at 2 weeks [n] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacro | Cont | Tacro | Cont | Tacro | Cont | Tacro | Cont | |||||||||

| Ogata et al. 200610 | Adult | 0.05mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml [high trough groupa] and 5–10ng/ml [low trough group] kept for 2 weeks | Placebo | 2 weeks of RCT and 10 weeks of open-label extension | PP | 4 | Reduction in DAI ≥ 4 with improvement of all categories | DAI score ≤2, with no individual subscore > 1 | 19b | 20 | 5/14 | 5/15 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Ogata et al. 201211 | Adult | 1–2.5mg PO twice daily, trough level of 115ng/ml kept for 2 weeks | Placebo | 2 weeks of RCT and 10 weeks of open-label extension | PP | 5 | Reduction in DAI ≥ 4 with improvement of all categories | DAI score ≤ 2 with individual subscore of 0 or 1 | 32 | 30 | NA [all were resistant or dependent] | 16 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

UC, ulcerative colitis; tacro, tacrolimus, cont, controls; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol; DAI, disease activity index score; PO, per os [by mouth]; RCT, randomised controlled trial; NA, not available.

aData shown are of the high trough group.

bTwo patients were excluded from efficacy analysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of observational studies of tacrolimus in active UC.

| Study, year, [reference] | Age | Tacrolimus dosage and schedule of therapy | Mean tacrolimus treatment duration [months] | Concomitant medications for UC | Study design | Follow-up duration [months] | Definition of clinical response | Patients [n] | Steroid resistant/ dependent [n] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High trough tacrolimus concentrations during induction therapy | Hogennauer et al. 200321 | Adult/paediatric | 0.15mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 1020ng/ml | 3.75 | Steroids tapered by 10mg/week. AZA was added after achieving improvement | Retrospective study | 2–47 | Reduction of modified TrueloveWitts score ≥ 3 | 9 | 9/0 |

| Ziring et al. 200722 | Paediatric | 0.2mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for the first 2 weeks, followed by 7–12ng/ ml | 5.62 | Steroids tapered by 5–10mg/week | Retrospective study | 4–48 | Absence of clinical symptoms | 18 | 9/9 | |

| Yamamoto et al. 200823 | Adult/paediatric | 23 pts received 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml. 4 pts received 0.01mg/kg/day IV, then switched to PO |

11 | NA | Retrospective study | 2–65 [median 17] | NA | 27 | 7/18 | |

| Benson et al. 200824 | NA | 0.2mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–12ng/ml | 7 | NA | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 32 | 13/8 | |

| Murano et al. 201125 | NA | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml | NA | NA | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 27 | 22/5 | |

| Inoue et al. 201226 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10– 15ng/ml, followed by 5–10ng/ml | 5.25 | NA | Retrospective study | 4–20 | Lichtiger score <1 0 and decrease ≥ 3 | 10 | 0/5 | |

| Hiraoka et al. 201327 | Adult/paediatric | 0.05–0.15mg/kg/ day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ ml | NA | NA | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 47 | NA | |

| Matsuura et al. 201328 | Adult/paediatric | PO or IV, trough level of 10–15ng/ ml for induction and 5–10ng/ml for maintenance | 10 | Steroids tapered and switched to AZA; 6 pts who did not respond received IFX | Retrospective study | 2–107 [median 24] | NA | 50 | NA | |

| Miyoshi et al. 201329 | Adult | 5mg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for 2 weeks, followed by 5–10ng/ml | 7 | NA | Retrospective study | 3–29 [median 16 ] | Lichtiger score ≤ 10 | 51 | 30/18 | |

| Boschetti et al. 201430 | Adult | 0.1–0.15mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for 12 weeks, followed by 5–10ng/ml for maintenance | NA | 18 pts received 5-ASA, 4 pts received steroids. None received concomitant AZA/6-MP or biologicals | Retrospective study | 12 | Reduction of modified DAI ≥ 2 | 30 | NA | |

| Ikeya et al. 201531 | Adult/paediatric | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for induction and 5–10ng/ml for maintenance | NA | NA | Retrospective study | 3 or more | NA | 44 | 13/24 | |

| Minami et al. 201532 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/day PO or 0.01mg/kg/day IV, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for induction | NA | 21 pts received 5-ASA, 12 pts received PSL, 6 pts received AZA, 13 pts received leukocyte apheresis, 2 pts who did not respond received IFX | Retrospective study | 0.5–118 [median 27] | NA | 22 | 12/6 | |

| Kawakami et al. 201533 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for 2 weeks, and 5–10ng/ ml for maintenance | NA | 5-ASA, steroids, and/or AZA or 6-MP | Prospective study | 1 | Lichtiger score < 10 and a decrease ≥ 3 | 49 | 38/13 [2 pts were included in both groups] | |

| Nakamura et al. 201534 | NA | PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for 2 weeks, 5–10ng/ml for maintenance | 7 | NA | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 71 | 71/0 | |

| Watanabe et al. 201535 | NA | PO, trough level of 10–15ng/ml for 2 weeks, 5–10ng/ml for maintenance | NA | NA | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 47 | 47/0 | |

| Low trough tacrolimus concentrations during induction therapy | Baumgart et al.200636 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/ day PO, trough level of 4–8ng/ml; 2 pts with toxic megacolon initially received 0.01mg/ kg/day IV | 25.2 | NA | Retrospective study | NA | Reduction of modified clinical activity index ≥ 4 | 40 | 26/14 |

| Ng et al. 200737 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 5–10ng/ml | NA | 2 pts received steroids. 3 pts received balsalazide, 2 pts received 6MP, 1 pt received AZA | Retrospective study | Median 8 | Inactive disease score on the TrueloveWitts criteria | 6 | NA | |

| Schmidt et al. 201338 | Adult | 0.1mg/kg/day PO; 10 pts initially received 0.01mg/ kg IV with a fast switch to PO. Median trough concentration within 4 weeks in 78 pts was 6.9ng/ml | NA | Steroids tapered individually. AZA [2–2.5mg/ kg/day] or 6-MP [1–1.5mg/kg/ day] continued in some pts. MTX [15–25mg/week] used in 4 pts | Retrospective study | 3 | NA | 130 | 130/0 | |

| Landy et al. 201339 | Adult/paediatric | 0.1mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 5–10ng/ml | 9 | 13 pts received PSL, 6 pts were concurrently treated with AZA | Retrospective study | 3–66 [median 27] | Reduction of modified TrueloveWitts score ≥ 4 | 25 | 25/0 | |

| Navas-Lopes et al. 201440 | Paediatric | 0.12mg/kg/day PO, trough level of 5–10ng/ml | 4.7 | NA | Retrospective study | 24 or more | Improvement of clinical symptoms or laboratory parameters, or reduction of PUCAI ≥ 20 | 10 | 10/0 | |

| Tacrolimus trough concentrations unavailable | Fellermann et al. 19988 | Adult/paediatric | 0.01–0.02mg/kg/ day IV for 7 days, then switched to 0.1–0.2mg/kg/day PO. Trough level: NA | 7 | PSL [1mg/kg IV till Day 7, 1mg/ kg PO Days 7-14], 5-ASA [3–4g/day], AZA [1.5–2.5mg/ kg] | Prospective study | 4–16 | NA | 6 | 6/0 |

| Fellermann et al. 200241 | NA | 18 pts received 0.01–0.02mg/ kg/day IV up to 14 days, then switched to 0.1–0.2mg/kg/day PO; 20 pts were started on PO. Trough level: NA | 7.6 | AZA or 6-MP added in some patients. Steroids were tapered after achieving improvement | Retrospective study | NA | NA | 38 [5 indeterminate colitis] | 38/0 | |

| Kimura et al. 201342 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Retrospective study | NA. | NA | 42 | 42/0 |

Adult, age ≥ 18; paediatric, age <18 years.

UC, ulcerative colitis; pts, patients; PSL, prednisolone; AZA, azathioprine; 6-MP, mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; IFX, infliximab; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; DAI, disease activity index; IV, intravenous; PO, per os [by mouth]; NA, not available; PUCAI, paediatric ulcerative colitis activity index.

In all, 23 observational studies reported the efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory UC patients: eight studies were performed in adult patients; two studies in paediatric patients [less than 18 years old]; and seven studies were performed in both adult and paediatric patients. There was no description about age of patients in six studies. There were 13 studies that described the mean duration of tacrolimus therapy [3.75–25.2 months] and 14 studies that described the follow-up period [0.5–118 months].

3.2. Meta-analysis of RCTs

Two RCTs comparing high target serum trough concentration [10–15ng/ml] versus placebo were included in our meta-analysis [Table 1]. Both were multicentre placebo controlled RCTs with high quality [Jadad score 4–5] and together comprised 103 patients with active steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent UC.

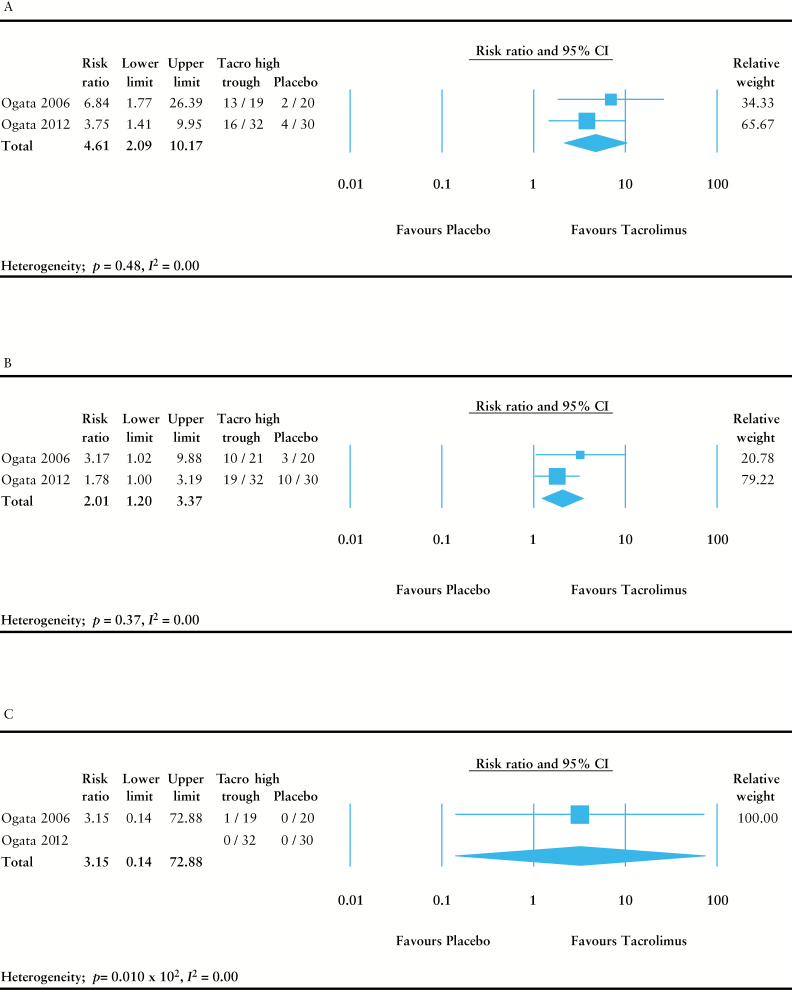

Tacrolimus induced a significantly higher rate of clinical response at 2 weeks compared with placebo (risk ratio [RR] = 4.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.09–10.17, p = 0.15 x 10-3) [Figure 2A]. Number needed to treat was 2.23 [95% CI = 1.64–3.50]. Rates of remission or mucosal healing could not be combined due to lack of data in either of the studies. There were no patients that underwent colectomy during the study period in either of the RCTs. Tacrolimus caused significantly higher drug-related adverse events compared with placebo [RR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.20–3.37, p = 0.83 x 10-2], but there was no difference in severe adverse events [RR = 3.15, 95% CI = 0.14–72.9, p = 0.47] [Figure 2B, C].

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Random-effects meta-analysis was performed to compare the efficacy between tacrolimus and placebo. [A] Clinical response at 2 weeks. [B] Treatment-related adverse event rate at 2 weeks. [C] Severe adverse event rate at 2 weeks.

3.3. Meta-analysis of observational studies

There were 23 prospective and retrospective observational studies with a total of 831 patients included in our analysis [Table 2]. More than 80% of the patients included in the study were steroid-refractory UC patients, with the remainder being steroid-dependent cases. Most of the studies were among adult patients, but some were performed among the paediatric population. More than 92% of the patients received tacrolimus per os [by mouth; PO] and only a small proportion received it intravenously.

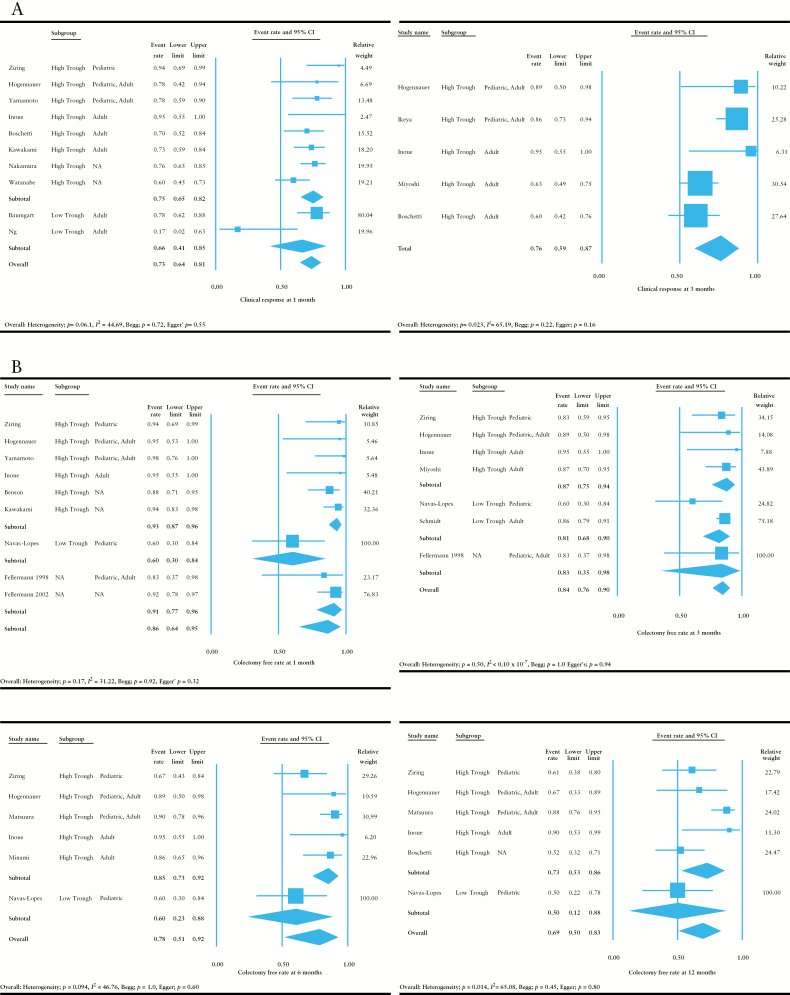

As shown in Figure 3A, tacrolimus demonstrated high rates of clinical response at 1 [0.73, 95% CI = 0.64–0.81] and 3 months [0.76, 95% CI = 0.59–0.87] among the observational studies. At 1 month, the clinical response rate was numerically, but not significantly, higher among the studies that administered tacrolimus at a high trough concentration [> 10ng/ml] as compared with those that administered it at a low trough concentration [< 10ng/ml]. There was moderate to high heterogeneity in these analyses [I 2 = 44.69 at 1 month and I 2 = 65.29 at 3 months].

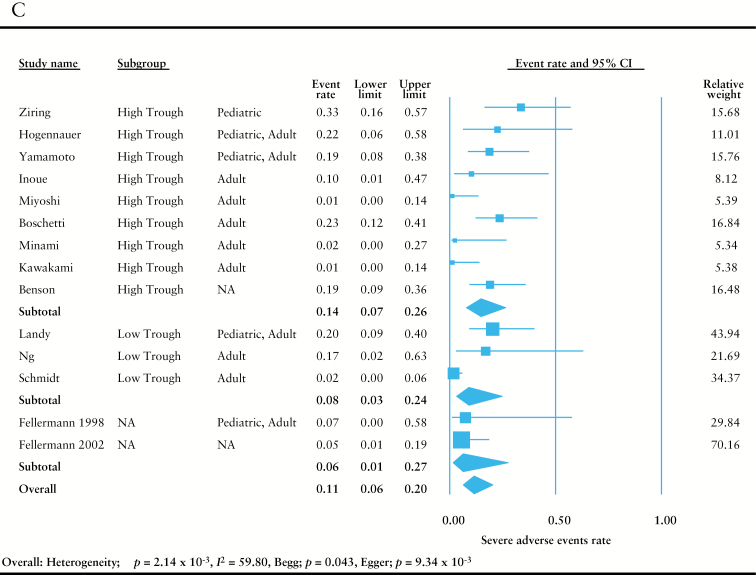

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of observational studies. Random-effects meta-analysis was performed to assess the efficacy of tacrolimus. [A] Analysis of the rate of clinical response at 1 and 3 months. [B] Analysis of colectomy-free rates at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. [C] Analysis of the rate of severe adverse events. Adult indicates patient population was ≥ 18 years old; paediatric indicates patient population was < 18 years old.

Colectomy-free rates remained high at 1 [0.86, 95% CI = 0.64–0.95], 3 [0.84, 95% CI = 0.76–0.90], 6 [0.78, 95% CI = 0.51–0.92], and 12 months [0.69, 95% CI = 0.50–0.83] [Figure 3B]. The rates were numerically higher among the studies that administered tacrolimus at a high trough concentration [> 10ng/ml] as compared with those that administered it at a low trough concentration [< 10ng/ml] at the induction phase. There was moderate to high heterogeneity in each of the analyses at 1, 6, and 12 months [I 2 = 31.22 at 1 month, I 2 < 0.10 x 10–7 at 3 months, I 2 = 46.76 at 6 months, and I 2 = 65.08 at 12 months]. The relatively high heterogeneity was thought to be due to differences in the backgrounds of the studies. No publication bias was noted in these analyses as assessed by Begg’s and Egger’s tests.

Incidents of severe adverse events were rare among the observational studies [0.11, 95% CI = 0.06–0.20] [Figure 3C]. There was high heterogeneity [I 2 = 59.80] and some publication bias was noted in this analysis [Begg: p = 0.043, Egger: p = 9.34 x 10–3]. This heterogeneity and publication bias were thought to be due to differences in the background of the observational studies, and the possibility of the presence of unreported studies, respectively. Subgroup analysis among different trough concentrations at the induction phase demonstrated similar results.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of tacrolimus in active UC. Meta-analysis of RCTs showed superiority of tacrolimus over placebo in inducing short-term clinical response. Meta-analysis of observational studies showed high rates of short-term clinical response as well as high colectomy-free rates that persisted over a period of 1 year.

Approximately 25% of patients with UC experience a severe flare during their disease course, requiring hospitalisation and high-dose corticosteroid therapy,4 which puts them at risk for colectomy.5 Intravenous ciclosporine has shown excellent short-term outcome as a salvage therapy in patients with severe steroid-refractory UC,14 but its use is limited to tertiary centres due to the difficulty of management and high risk for adverse effects. More recently, infliximab has shown comparable effect to ciclosporine in this setting.43 Tacrolimus has a similar mechanism of action to ciclosporine, and has been more commonly used than ciclosporine in organ transplants.44 The aim of our systematic review and meta-analysis was to combine data and to assess the efficacy of tacrolimus in severe and steroid-refractory UC.

We identified two RCTs that compared tacrolimus with placebo therapy in moderate-severe steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent UC. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that tacrolimus was significantly more effective than placebo in inducing short-term clinical response at 2 weeks. This result was supported by the meta-analysis of 23 observational studies, which showed similarly high clinical response rates at 1 and 3 months. One major issue in the setting of treating severe UC is the poor long-term outcome including the risk of colectomy. Indeed, the majority of the observational studies associated with ciclosporine have shown that approximately 50% of patients will undergo colectomy in 1–2 years.6 We showed that colectomy-free rates remained high at 70–90% during a follow-up of up to 12 months among the observational studies.

The use of calcineurin inhibitors is associated with various side effects including kidney injury, tremor, and infections.16,45,46 This is one of the reasons why its use is limited to tertiary centres with more experience in patient care. Among the RCTs and observational studies included in our meta-analysis, there were 38 patients among 11 studies who experienced severe adverse events.8,10,21,22,23,24,26,30,37,38,39 All of them improved with discontinuation or reduction of tacrolimus and some of the patients were treated medically according to their symptoms. Whereas the rate of overall adverse effects was more common with tacrolimus compared with placebo therapy in RCTs, the risk of serious adverse effects was not increased with tacrolimus. Among the 14 observational studies which reported the incidence of severe adverse effects, the duration of tacrolimus therapy was specified in 9 studies,8,21,22,23,24,26,29,39,41 which ranged from 3.75 to 11 months. The combined risk of adverse effects with tacrolimus among observational studies was low, supporting its long-term safety.

The shortcoming of our study is the small number of RCTs directly comparing tacrolimus with placebo. However, both studies were of good quality as shown by a median Jadad score of 4.5. Furthermore, meta-analysis of observational studies demonstrated similarly high rates of short-term response to tacrolimus therapy, supporting the result of the meta-analysis of RCTs. The RCT undertaken by Ogata et al. demonstrated that tacrolimus is more effective when given at a high trough level of 10–15ng/ml10, and close therapeutic drug monitoring to keep it in that range is now standard care. However, some of the observational studies, especially those undertaken prior to the studies by Ogata et al. and paediatric studies, lacked information regarding the trough levels or administered it at a lower trough level. This may have underestimated its effect or led to higher rates of adverse reactions.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that tacrolimus was effective in inducing short-term clinical response in active UC patients, with a durable effect of preventing colectomy without increased risk of severe adverse events. The use of tacrolimus is warranted in severe and steroid-refractory UC.

Funding

AS was supported by the Foreign Clinical Pharmacology Training Program of the Japanese Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

YK and FK: analysis of data and drafting of manuscript; AI: critical review and approval of manuscript: AS, study concept and design, analysis of data, and writing of manuscript.

Reference

- 1. Hibi T, Ogata H. Novel pathophysiological concepts of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sakuraba A, Sato T, Kamada N, et al. Th1/Th17 immune response is induced by mesenteric lymph node dendritic cells in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1736–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakuraba A, Sato T, Matsukawa H, et al. The use of infliximab in the prevention of postsurgical recurrence in polysurgery Crohn’s disease patients: a pilot open-labeled prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dinesen LC, Walsh AJ, Protic MN, et al. The pattern and outcome of acute severe colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, et al. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kobayashi T, Naganuma M, Okamoto S, et al. Rapid endoscopic improvement is important for 1-year avoidance of colectomy but not for the long-term prognosis in cyclosporine A treatment for ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol 2010;45:1129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katz JA. Medical and surgical management of severe colitis. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2000;11:18–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fellermann K, Ludwig D, Stahl M, et al. Steroid-unresponsive acute attacks of inflammatory bowel disease: immunomodulation by tacrolimus [FK506]. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naganuma M, Fujii T, Watanabe M. The use of traditional and newer calcineurin inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol 2011;46:129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, et al. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus [FK506] therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut 2006;55:1255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus [FK506] in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:803–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stenke E, Hussey S. Ulcerative colitis: management in adults, children and young people [NICE Clinical Guideline CG166]. Arch Dis Child Pract Ed 2014;99:194–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsuoka K, Hibi T. Treatment guidelines in inflammatory bowel disease: the Japanese perspectives. Dig Dis 2013;31:363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1841–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang KH, Burke JP, Coffey JC. Infliximab versus cyclosporine as rescue therapy in acute severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorect Dis 2013;28:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The U. S. Multicenter FK506 Liver Study Group. A comparison of tacrolimus [FK 506] and cyclosporine for immunosuppression in liver transplantation. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 21. Hogenauer C, Wenzl HH, Hinterleitner TA, et al. Effect of oral tacrolimus [FK 506] on steroid-refractory moderate/severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18:415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziring DA, Wu SS, Mow WS, et al. Oral tacrolimus for steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45:306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Mikami S, et al. Long-term effect of tacrolimus therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benson A, Barrett T, Sparberg M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus in refractory ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murano M, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Induction Therapy of Tacrolimus With Severe Ulcerative Colitis Refractory to Steroid Therapy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:AB442. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, et al. The efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with moderate/severe ulcerative colitis not receiving concomitant corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med 2013;52:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hiraoka S, Kato J, Inokuchi T, et al. Prediction of Dose of Tacrolimus Required for Remission Induction of Ulcerative Colitis Patients. BMC Gastroenterol 2015;15:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsuura M, Nakase H, Yoshino T, et al. Long-term follow-up in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with tacrolimus: early and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:S190. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miyoshi J, Matsuoka K, Inoue N, et al. Mucosal healing with oral tacrolimus is associated with favourable medium- and long-term prognosis in steroid-refractory/dependent ulcerative colitis patients. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boschetti G, Nancey S, Moussata D, et al. Tacrolimus induction followed by maintenance monotherapy is useful in selected patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis refractory to prior treatment. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ikeya K, Sugimoto K, Kawasaki S, et al. Tacrolimus for remission induction in ulcerative colitis: Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 and 1 predict long-term prognosis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Minami N, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Tacrolimus or infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis: short-term and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2015;2:e000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, et al. Effects of oral tacrolimus as a rapid induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:1880–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamura M, Hida N, Iimuro M, et al. Incidence and Severity of Acute Kidney Injury During Oral Tacrolimus Treatment in Patients With Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2015;148:S-237. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watanabe O, Nakamura M, Yamamura T, et al. The Efficacy of Tacrolimus and the Usefulness of Endoscopy in Predicting Its Efficacy in Patients With Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:AB240. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baumgart DC, Pintoffl JP, Sturm A, et al. Tacrolimus is safe and effective in patients with severe steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease—a long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ng SC, Arebi N, Kamm MA. Medium-term results of oral tacrolimus treatment in refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt KJ, Herrlinger KR, Emmrich J, et al. Short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis-experience in 130 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Landy J, Wahed M, Peake ST, et al. Oral tacrolimus as maintenance therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis-an analysis of outcomes in two London tertiary centres. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Navas-Lopez VM, Blasco Alonso J, Serrano Nieto MJ, et al. Oral tacrolimus for paediatric steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:64–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fellermann K, Tanko Z, Herrlinger KR, et al. Response of refractory colitis to intravenous or oral tacrolimus [FK506]. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2002;8:317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimura K, Matsuoka K, Miyoshi J, et al. The switching therapy between infliximab and tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:S144–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:1909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kur F, Reichenspurner H, Meiser B, et al. Tacrolimus [FK506] as primary immunosuppressant after lung transplantation. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;47:174–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Margreiter R; Group ETvCMRTS. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus compared with ciclosporin microemulsion in renal transplantation: a randomised multicentre study. Lancet 2002;359:741–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kong Y, Wang D, Shang Y, et al. Calcineurin-inhibitor minimization in liver transplant patients with calcineurin-inhibitor-related renal dysfunction: a meta-analysis. PloS One 2011;6:e24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]