Abstract

Astrocytes are abundant glial cells that tile the entire central nervous system and mediate well established functions for neurons, blood vessels and other glia. These ubiquitous cells display intracellular Ca2+ signals, which have been intensely studied for 25 years. Recently, the use of improved methods has unearthed the panoply of astrocyte Ca2+ signals and a variable landscape of basal Ca2+ levels. In vivo studies have started to reveal the settings under which astrocytes display behaviorally relevant Ca2+ signaling. Studies in mice have emphasized how astrocyte Ca2+ signaling is altered in distinct neurodegenerative diseases. Progress in the last few years, fueled by methodological advances, has thus reignited interest in astrocyte Ca2+ signaling for brain function and dysfunction.

Keywords: astrocyte, calcium, imaging, GCaMP, AAV

Introduction

Astrocytes tile the central nervous system and may represent ∼20-40% of the total number of brain cells [1]. Their highly branched morphology, including proximity to neurons and blood vessels, has been the subject of intrigue, speculation and study ever since astrocytes were discovered ∼150 years ago. It is now well established that astrocytes serve diverse and important roles for the brain to function as an organ. These include roles for astrocytes in ion homeostasis, neurotransmitter clearance, synapse formation/removal, synaptic modulation and contributions to neurovascular coupling, all of which are reviewed elsewhere [2-4]. From these perspectives, attention has focussed on astrocyte intracellular Ca2+ signals as a basis to measure, interrogate and ultimately understand their roles within neural circuits [2, 5]. The strong focus on Ca2+ is based on the knowledge that Ca2+ is a widely used and important second messenger and on the realisation that astrocytes, unlike neurons, are electrically not excitable [6].

The possibility that astrocytes may contribute to neural circuit function was first proposed almost 25 years ago [7, 8], soon after astrocyte Ca2+ signals were discovered [5]. Since then astrocyte Ca2+ signals have been studied in detail. In this review, we focus on recent insights on the properties of astrocyte Ca2+ signals, on emerging studies of astrocyte basal Ca2+ levels and on their relation to two exemplar neurodegenerative disease models and behavior. Recent breakthroughs in the astrocyte field over the last few years have been fueled by technical advances that allow Ca2+ signals to be studied reliably in physiologically relevant compartments both ex vivo in brain slices and in vivo in adult mice.

Genetically-encoded calcium indicators (GECIs)

Organic Ca2+ indicator dyes, delivered to astrocytes by bulk loading or by intracellular dialysis using patch pipettes, have proven useful to study astrocytes [5]. Fundamental insights have emerged from their use [9-13]. These include the discovery of astrocyte Ca2+ signals [14-16] and two decades of work on their relation to neuronal activity [10, 17], including the first studies of astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics in vivo [18]. However, astrocytes are problematic to load with organic Ca2+ indicator dyes in adult brain slices. Moreover, in vivo repeated chronic imaging experiments are problematic because the dyes are lost from the cells over time, and organic dyes clearly only reveal the astrocyte's somata [19]. Hence additional approaches were needed. We focus here on recent studies employing GECIs, which comprise a single polypeptide chain of a fluorescent protein (or proteins) and a Ca2+ binding motif [20-22]. These largely overcome the aforementioned limitations of organic Ca2+ indicator dyes for the study of astrocytes.

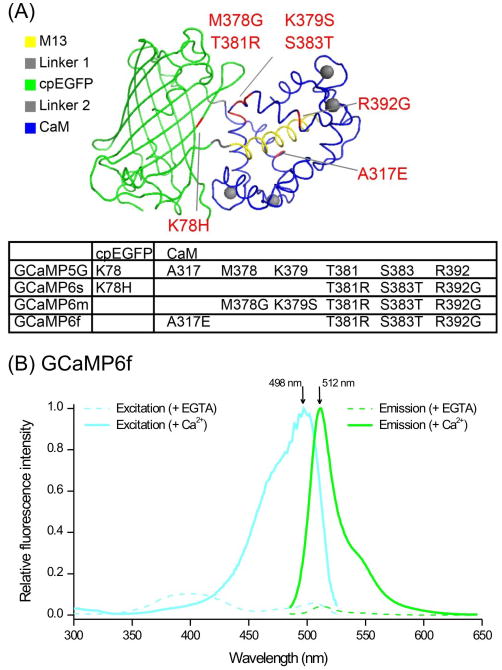

Two types of GECIs have been used in astrocyte studies: single wavelength GECIs such as the GCaMP series (Figure 1), and FRET based ratiometric GECIs, such as the Yellow Cameleons [20]. GCaMPs are derived from circularly permuted enhanced GFP, the M13 peptide from myosin light chain kinase and calmodulin (Figure 1) [23]. In the absence of Ca2+, GCaMPs display weak fluorescence, but upon Ca2+ binding (to calmodulin) increased green fluorescence is observed. GCaMPs have been optimized in terms of brightness, signal-to-noise, dynamic range, Ca2+ affinity and photostability [24-27]. The latest GCaMP6 series developed by the Janelia GENIE Project performs as well as some organic Ca2+ indicator dyes [24]. The properties of GCaMPs are further leveraged by targeting them to sub cellular compartments such as the plasma membrane [28-31], mitochondria [32-34] and endoplasmic reticulum [33, 35]. Ratiometric FRET based GECIs are also widely used and have been improved to tune Ca2+ affinity to desirable levels [36]. The design and evolution of GECIs has been reviewed [20, 22].

Figure 1. GCaMPs.

(A) Structure of GCaMP showing the modular nature of the molecule and the locations of mutations in different GCaMP6 variants relative to GCaMP5G. The panel is reproduced from the paper reporting the development of GCaMP6f [24]. (B) Excitation and emission spectra of GCaMP6f in solution in the absence and presence of Ca2+. The spectra were provided by the Janelia GENIE Project; further biophysical properties have been published [24].

GECIs have been targeted to astrocytes using several techniques, including in utero electroporation, adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), as well as transgenic and knock-in approaches (Table 1). These versatile proteins have features of relevance to astrocytes: i. cell specific targeting increases signal-to-noise, especially in relation to organic dyes [28]; ii. GECIs are stably expressed for weeks without noticeable deleterious effects, permitting chronic repeated imaging experiments in vivo [37, 38]; iii. GECIs generally display little bleaching during acute imaging experiments [28]; and iv. GECIs reveal Ca2+ signals from entire astrocytes [28]. Thus, GECIs overcome some of the limitations [5, 19] of organic Ca2+ indicators to study astrocytes.

Table 1. Strategies to express GECIs in astrocytes.

| GECI | Expression approach | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Cytosolic Yellow cameleon 3.60 mice | Transgenic mice driven by the S100β promoter | [49] |

| Cytosolic GCaMP3 and GCaMP6f | AAV 2/5 using the GfaABC1D promoter, in utero electroporation | [28, 31, 38, 42-44, 47] |

| Membrane tethered GCaMP3 and GCaMP6f (Lck tagged) | AAV 2/5 and GfaABC1D promoter, in utero electroporation | [28, 31, 43, 44, 47] |

| Cytosolic GCaMP3 mice | Knock-in at the ROSA26 locus | [37, 41] |

| Cytosolic YC-nano50 mice | Knock-in using tetracycline transactivator (tTa)-tet operator (tetO) strategy at Actb locus | [48] |

| Cytosolic GCaMP5G mice | Knock-in at the Polr2a locus | [53] |

| Cytosolic GCaMP6f and GCaMP6s mice | Knock-in mice at the ROSA26 and TIGRE loci | [38, 56] |

GECIs are not a panacea, however, and they come with features and considerations that need to be taken into account for each experiment. Thus GECIs, like all Ca2+ indicators, have the potential to buffer Ca2+ and therefore alter astrocyte physiology. As far as we know, this has not proven to be a problem, but needs to be considered. The concentration of GECIs inside cells is largely unknown and is expected to differ between expression strategies (Table 1). A conservative estimate suggests that GECIs are expressed in the tens of micromolar concentration range [31]. Moreover, the affinity of available GECIs should be considered for each specific experiment; this parameter can be tuned by mutagenesis [39]. The on- and off-kinetics of many GECIs are slower than those of organic indicator dyes, but the GCaMP6 series is the fastest [24]. Of note, high expression of GFP in astrocytes is known to cause astrogliosis [40] and expression of GECIs over several months decreases the health of neurons [41]. Thus, long-term GECI expression in astrocytes may be problematic, especially with AAV-based expression methods [41]. Hence, GECI expression strategies need to be validated on a case-by-case basis as in published studies for cortex, hippocampus and striatum [28, 38, 42-44]. In addition, although AAV-mediated GECI delivery has proven powerful, one has to consider that surgical delivery of AAVs unavoidably damages brain tissue, and thus the cells that are imaged are usually located distally to the microinjection site. This strategy works well for large brain structures such as cortex, hippocampus and striatum, but may be problematic for small brain nuclei. In these cases, independent assessment of damage is needed. In utero electroporation has clear advantages for studying astrocytes during development, in neonatal mice and for rats for which gene targeting strategies are less well developed [31]. With the use of Cre-dependent knock-in mouse lines, one needs to consider the specificity of the Cre line and the proportion of astrocytes targeted in a given brain area. For example, GLAST-Cre/ERT2 targets GECIs to ∼35% of astrocytes in the cortex, ∼40% in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and close to 100% of Bergmann glia in the cerebellum [37, 38]. Most glial fibriliary acidic protein (GFAP)-Cre lines result in expression within populations of neurons and astrocytes and are not suited for expressing GECIs selectively within astrocytes [45, 46].

Ca2+ signals were recently compared for hippocampal astrocytes when GCaMP3 or GCaMP6f were expressed using AAV or using GCaMP3 and GCaMP6f knock-in mice [38, 43]. The data were indiscernible. Furthermore, GECIs have been deployed in several studies and no untoward effects have been reported [26, 28-32, 37, 38, 42-44, 47-55]. In future astrocyte studies, appropriate controls will still be needed.

Astrocyte Ca2+ signals

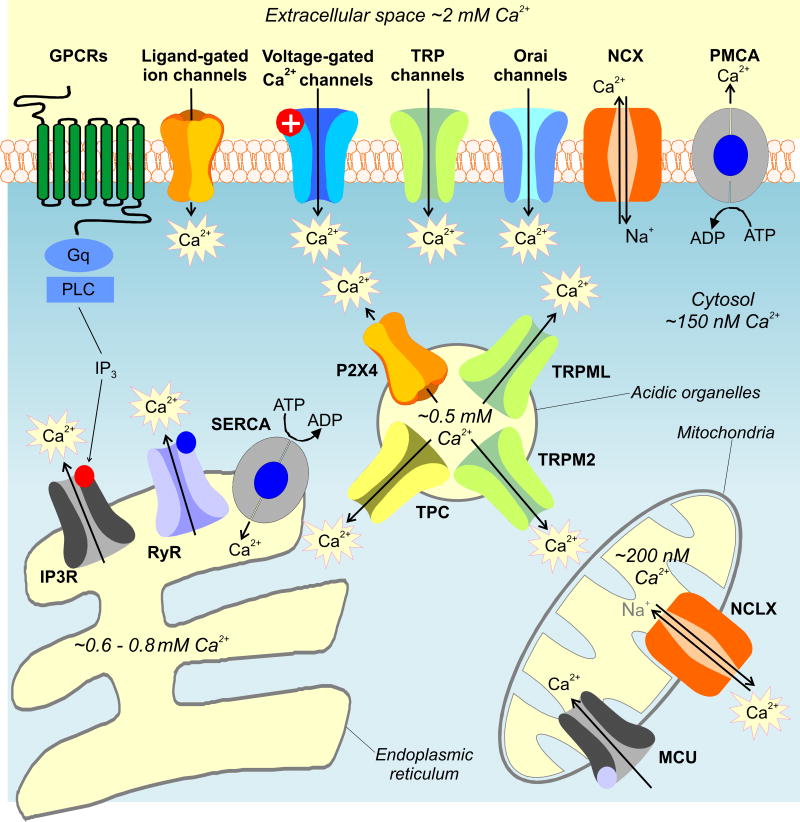

Ca2+ signaling is a mature field in cell biology. Nonetheless, despite progress, major questions concerning astrocyte Ca2+ signaling remain to be satisfactorily addressed [5]. This is probably because multiple potential sources of Ca2+ have not been explored and hence not convincingly ruled in or out (Figure 2, Key Figure). These include receptors, channels, exchangers and pumps on the plasma membrane, as well as within intracellular organelles such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi and acidic organelles (Figure 2). These sources and sinks exploit Ca2+ concentration gradients between cellular compartments [58-60]. In going forward, it will be important to consider the possibility that astrocytes, like other cells, contain multiple sources of Ca2+ and that the relative contributions of each may change depending on the brain area [1, 61, 62]. Notably, recent cell specific proteomics shows that ∼85% of proteins are shared between major brain cell types [63], implying that several plausible Ca2+ sources known to exist in other cell types merit detailed study in astrocytes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Key Figure: Ca2+ transport in cells.

The cartoon shows various sources and sinks for Ca2+ in cells. In going forward, these need to be considered carefully in studies of astrocytes. Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ are dynamically regulated through interplay between Ca2+ channels, pumps and transporters. A variety of Ca2+ channels exist which are expressed on both the plasma membrane and the membrane of organelles. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are highly selective plasma membrane proteins that mediate Ca2+ signals in excitable cells in response to membrane depolarization. A number of neurotransmitters mediate Ca2+ signals through less-selective ligand-gated ion channels. These include cell surface P2X receptors activated by ATP and the NMDA class of ionotropic receptors for glutamate (NMDAR). Nicotinic acetylcholine (AChR) and 5-HT3 (5HT3R) receptors are Ca2+-permeable members of the cys-loop family of ligand-gated ion channels activated by acetylcholine and 5-HT, respectively. TRP channels constitute a large family of widely expressed ion channels. They are divided into 6 families in mammals. Their Ca2+ selectivity varies widely and they are activated by a number of intracellular and extracellular cues including heat (e.g. TRPV1), cold (e.g. TRPM8), pungent chemicals (TRPA) and Ca2+ itself (TRPP2). TRPC channels are activated upon receptor-mediated signaling downstream of phospholipase C signaling via diacylglycerol in some cases. Orai channels are highly Ca2+-selective channels activated by the ER Ca2+ sensor STIM upon depletion of ER Ca2+ stores. Plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) pumps and sodium-calcium exchangers (NCX) transport Ca2+ out of the cytosol. IP3 receptors are intracellular Ca2+-permeable channels localized predominately to the ER where they mediate Ca2+ signals in response to IP3 produced upon phospholipase C activation, which occurs downstream of GPCR activation. Receptor stimulation also elevates levels of, cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) which activates the related ryanodine receptors (RyR). The ER Ca2+ stores are filled by sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCA The Golgi complex (not shown) also acts as a dynamic Ca2+ store housing IP3 and ryanodine receptors for Ca2+ release and secretory pathway ATPases (together with SERCA) for filling. In addition to the ER, a number of acidic organelles which include lysosomes also serve as Ca2+ stores. These acidic Ca2+ stores express two-pore channels (TPCs), activated by the intracellular messenger NAADP, and TRPM2 activated by ADP-ribose (which additionally activates plasma membrane TRPM2). TRP mucolipins (TRPML) and P2X4 receptors are also expressed on lysosomes. Ca2+ is also dynamically regulated by mitochondria. Ca2+ is rapidly taken up by the mitochondrial uniporter (MCU) which is a Ca2+-permeable channel localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Ca2+ is slowly released back into the cytosol by the actions of a mitochondrially targeted sodium-calcium changer (NCLX). The Ca2+ concentrations for the intracellular compartments were taken from published work [58-60].

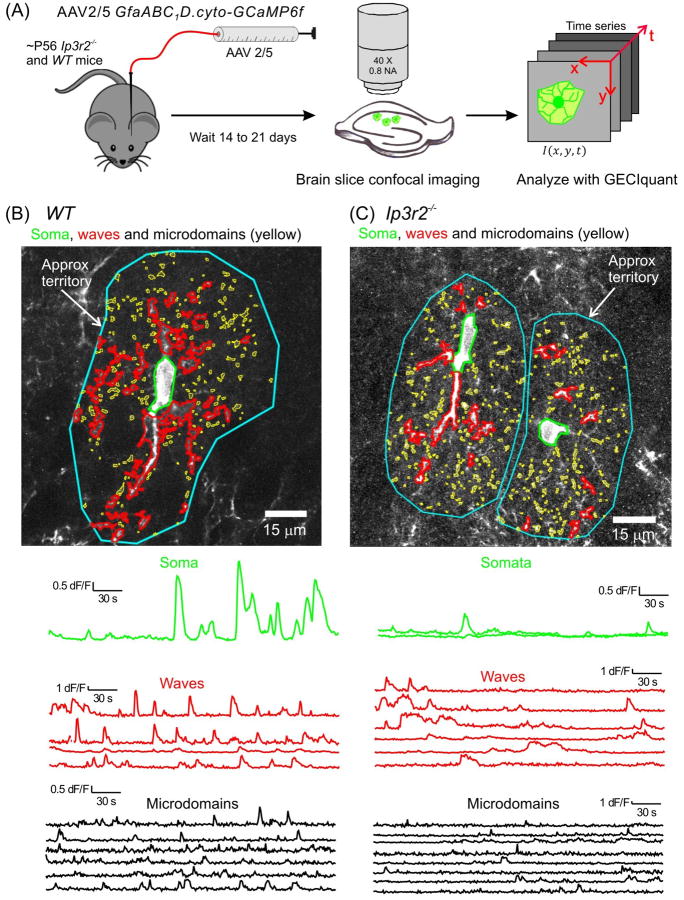

Ca2+ release from intracellular stores

GECIs have been particularly valuable to study Ca2+ signals in astrocyte branches and branchlets that have previously been difficult to explore [64]. A major mechanism for generating Ca2+ signals is through activation of inositol triphosphate (IP3) receptors which mediate Ca2+ release from the ER (Figure 2). Three isoforms of IP3 receptors exist in vertebrates (IP3R1-3). IP3R2s are enriched in astrocytes [65] and because astrocytes respond to many G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) agonists [66, 67] this IP3R2 mediated intracellular Ca2+ release pathway was expected to dominate. In accord, astrocytes that lacked IP3R2s appeared to lack spontaneous and GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signals [68] that were measured using organic Ca2+ indicators and Ca2+ signaling was reported to be “obliterated” in 100% of hippocampal astrocytes [68, 69]. The finding that the Ip3r2–/– mice also displayed no obvious neuronal deficits led the authors to the conclude that astrocyte Ca2+ signals were not involved in neuronal and behavioral responses [69, 70]. However, recent evaluations in brain slices and in vivo using the fast GECI GCaMP6f to measure Ca2+ signals in wild type and homozygous Ip3r2–/– adult mice, have provided new insights [38]. First, the overall pattern of Ca2+ signals within astrocytes was similar between hippocampal astrocytes in slices and cortical astrocytes in vivo for both wild type and Ip3r2–/– mice [38]. This shows that Ca2+ signals were not the consequence of the method employed, i.e. they were not detectably caused or altered by brain slice procedures. This is an important point, given past suggestions that astrocyte Ca2+ signaling was altered in brain slices under conditions used by some investigators [71]. Second, standardized semi-automated analyses of wild type and Ip3r2–/– mice showed IP3R2-independent Ca2+ signaling within astrocyte branches [38, 43]. Similar residual Ca2+ signals in astrocyte branches have been reported by others [48] and available data suggest that most physiological Ca2+ signaling actually occurs mainly in astrocyte branches and branchlets [28, 43, 72]. Consistent with these data, roles for IP3R1 and 3 in mediating residual Ca2+ signals in astrocytes from Ip3r2–/– mice has been suggested [73]. Strong stimuli were required to elicit somatic Ca2+ signals [43, 48, 72]. Consistent with these data, somatic Ca2+ signals were largely reduced in Ip3r2–/– mice, but those in branches were only partially reduced (Figure 3) [38]. However, astrocyte Ca2+ signals evoked by neuronal glutamate release were abolished in Ip3r2–/– mice [43]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the use of organic Ca2+ indicator dyes, which mainly reveal somatic compartments, led to the simplistic conclusion that spontaneous and GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes was abolished in Ip3r2–/– mice. The discovery of residual Ca2+ signals in Ip3r2–/– mice now necessitates the need for additional ways to impair Ca2+ signaling, for reevaluation of potential neuronal and cerebrovascular consequences [2] and for exploration of the full gamut of potential Ca2+ signals (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Ca2+ signals in hippocampal astrocytes from wild type and Ip3r2–/– mice.

(A) Schematic illustrating the experimental approach. AAVs were microinjected in vivo, brain slices were imaged ∼ 2 weeks later and Ca2+ signals analyzed in a semi automated manner using custom software called GECIquant. (B) Representative images and traces for Ca2+ signals measured in an astrocyte from a WT mouse. Three predominant types of Ca2+ signal are demarcated: somatic signals (green), waves (red) and microdomains (yellow). Approximate territory boundaries are outlined in blue. (C) As in B, but for two astrocytes from an Ip3r2–/– mouse; somatic signals are largely absent, but many signals persist in branches. Figure from a recent paper [38].

Ca2+ influx signals in astrocytes

Astrocytes interact with neurons via small finger-like structures [74, 75], which we term leaflets and branchlets. These display diameters on the tens of nanometer scale and are expected to have high surface area to volume ratios [76] and hence cannot be imaged directly with light microscopy. In addition, evanescent wave microscopy has shown that astrocytes display numerous near membrane Ca2+ signals [29, 30]. In light of these facts, the Lck tag has been used to recruit GECIs to the plasma membrane of astrocytes in vitro and in vivo following delivery with AAVs [28, 47] or in utero electroporation [31]. The Lck-tag is a 26 amino acid polypeptide including tandem myristoylation and palmitoylation domains - it results in essentially complete labeling of the astrocyte plasma membrane [77]. Lck-GCaMP3 revealed microdomain Ca2+ signals which occurred spontaneously and in a seemingly random fashion. These were termed “spotty Ca2+ signals” [29]. Pharmacological and genetic evaluations showed that spotty Ca2+ signals were mediated by Ca2+ influx through TRPA1 channels [30]. Subsequent slice experiments showed that they contributed to basal Ca2+ levels, which were necessary for the constitutive release of D-serine into the extracellular space [47] and for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter expression on the plasma membrane [30]. The wide use of GECIs has revealed other examples of broadly similar spotty Ca2+ signals in astrocytes in brain slices and in vivo; frequently they are called microdomains. However, their molecular basis remains to be determined (Figure 2). For example, in the CA3 region of the hippocampus, TRPA1 channels did not mediate Ca2+ microdomains and those observed in stratum radiatum astrocytes were only partially blocked by a TRPA1 antagonist [43, 47]; TRPV1 channels could be usefully explored in this context based on cell culture studies [78]. Region specific differences may explain why astrocytes in different circuits display Ca2+ signals from different sources, of differing duration and separable reliance on neuronal action potential firing [13, 43, 79]. Evaluations with GCaMP6f in the hippocampus show that ∼50% of spontaneous Ca2+ signals are dependent on transmembrane fluxes within astrocyte branches, but few if any are dependent on this pathway in the somata [38]. The spotty transmembrane fluxes probably locally elevate Ca2+ concentration by ∼300 nM, whereas G-protein coupled receptors globally elevate Ca2+ to at least 1 μM [29]. Further detailed molecular and biophysical analyses would be insightful.

Basal Ca2+ levels of astrocytes

In addition to Ca2+ signals, the basal Ca2+ level of cells is expected to be physiologically important. The basal level of Ca2+ within cultured hippocampal astrocytes was estimated to be ∼120 nM using ratiometric Fura-2 imaging [29]. However, these methods are prone to several well-known artifacts when used in complex tissues such as brain slices and in vivo (e.g. light absorption/scattering, movement, concentration inhomogeneities). As a result, the astrocyte basal Ca2+ concentration was estimated by 2-photon laser scanning microscopy (2PLSM) and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), an advanced method that measures the average time a fluorophore spends in the excited state before returning to the ground state [80]. The method overcomes many of the problems mentioned above, but requires specialized equipment. FLIM was used to measure the Ca2+ concentration of cortical astrocytes using Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) delivered by bulk loading in vivo [81]. The resting concentration of Ca2+ was found to be ∼84 nM, but was significantly elevated to ∼155 nM in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. The potential molecular pathways that determine basal Ca2+ levels in cortical astrocytes are currently unknown (Figure 2).

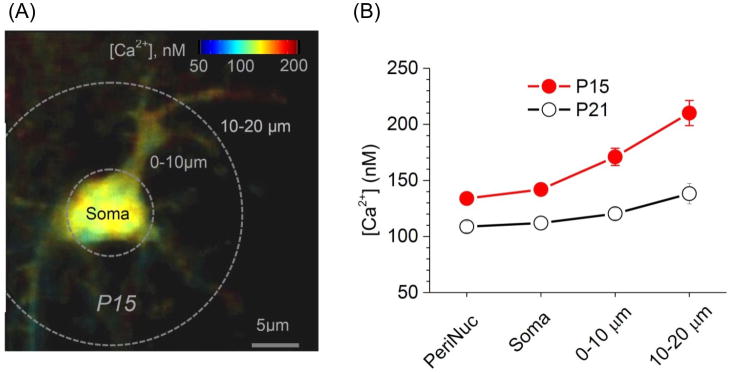

FLIM has recently been used with aplomb in a recent study to map astrocyte basal Ca2+ concentrations in hippocampal brain slices and for the cortex in vivo [82]. The study exploited the observation that the fluorescence lifetime of OGB-1 increases with increasing concentration of Ca2+ in the nanomolar range [83, 84]. A number of fundamental observations were made. First, the basal Ca2+ concentration of astrocytes was markedly higher than that of neurons in hippocampal brain slices. Second, the Ca2+ concentration in astrocytes that were loaded with OGB-1 via gap junction coupling was ∼100 nM near the soma, but increased to ∼125 nM towards the edges of single astrocytes, i.e. in areas that correspond to branches (Figure 4) where there is greater preponderance of Ca2+ fluxes [28, 38, 43, 72]. Third, the astrocyte basal Ca2+ concentration decreased dramatically between the ages of 14 and 21 days throughout the cell, but nonetheless maintained an increasing gradient outward from the soma (Figure 4). This recalls previous observations on the differences between young and adult mice for Ca2+ signaling [85]. Fourth, when basal Ca2+ was measured in many dozens of astrocytes, the cells segregated into two populations: one with a mean basal Ca2+ concentration of ∼70-75 nM and another at ∼120-130 nM. This observation was unexpected and made possible only because of FLIM. Fifth, there was remarkable concordance across the board for data gathered in vivo and in acute brain slices, again suggesting that the judicious use of brain slices is a useful way to study astrocytes within semi intact preparations.

Figure 4. Astrocyte basal Ca2+ levels are developmentally regulated.

(A) Characteristic Ca2+ concentration map in a gap junction-coupled astrocyte from a mouse aged 15 days. Note that the Ca2+ concentration increases towards the branches. (B) Distribution of resting Ca2+ in cellular compartments of gap junction-coupled astrocytes from images such as those in A. Two developmental ages are shown. The image is reproduced (with permission) from Figure 5 of a recent paper [82].

The realization that astrocyte basal Ca2+ levels are an important physiological attribute of astrocytes raises the all-important issue of their functional roles. In relation to this, work with brain slices prepares us for the possibility that changes in the basal Ca2+ concentration of astrocytes may have neuronal consequences by virtue of neurotransmitter uptake and D-serine release [30, 47]. Basal Ca2+ levels in astrocytes also play a key role in maintaining tonic blood flow by regulation of arteriole diameter [86]. More work is needed, but it is likely that additional functions of basal Ca2+ levels will emerge, for example setting of the sensitivity of Ca2+ sensitive Ca2+ release channels to activation upon GPCR engagement. The cytosol as an “excitable medium” in astrocytes might substitute for excitable behavior at the plasma membrane.

Astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in health and disease

Astrocyte Ca2+ signals in relation to behavior

Smith invoked the idea that astrocyte Ca2+ signals may affect the function of neural circuits [7, 8] and ultimately behavior. The use of GECIs and 2PLSM is now permitting exploration of this concept in vivo for whole astrocytes and entire fields of view containing many astrocytes, i.e. at sub cellular and macroscopic levels of investigation. The most relevant experiments are performed in awake behaving mice, because of the discovery that anesthesia largely abrogates astrocyte Ca2+ signals [87-89]. Astrocytes display robust Ca2+ elevations during locomotion. These were correlated in the cortex and Bergmann glia and reflect brain wide changes [37, 88]. The available data suggest that astrocytes respond to the endogenous release of noradrenaline during arousal or heightened vigilance states [37, 90]. Noradrenaline acts on α1 adrenoceptors, which in the simplest interpretation are located on astrocytes [37, 38, 90-93], although other neuromodulators such as acetylcholine may also contribute [94, 95]. α1 adrenoceptors could conceivably be located on another cell type and impact upon astrocytes indirectly. The responses were thus driven by a slow neuromodulator and were global in the sense that all astrocytes in the imaged field of view displayed elevations. Although abundant spontaneous Ca2+ signals in branches were observed [38], there was little evidence for local Ca2+ signals triggered selectively during startle responses, which implies that noradrenaline acts broadly as a volume transmitter. This effect of endogenously released noradrenaline was mainly, but not completely mediated by Ca2+ release from intracellular IP3R2-dependent Ca2+ stores [38]. Thus, a startle-evoked slow response persisted in astrocyte branches in the Ip3r2–/– mice [38]. Interestingly, responses of layer 2/3 visual cortex astrocytes to light were enhanced markedly by enforced locomotion [37], which suggests that local (visual stimulation) and global (locomotion/arousal) signals may act synergistically through as yet unknown molecular mechanisms. However, further studies are needed to determine if astrocyte responses during arousal have any relation to the change in gain of primary visual cortex layer 2/3 neurons during locomotion [96, 97], or if astrocyte responses mediated by noradrenaline can affect cortical synaptic function. The kinetics of the astrocyte responses appear too slow to affect the gain change of cortical neurons [37, 38], but refined tools to abolish astrocyte Ca2+ signals selectively and locally in the cortex are needed to explore this issue. Moreover, given that astrocytes are considered to be heterogeneous [62], future studies will need to evaluate astrocyte Ca2+ responses in vivo in genetically defined populations of astrocytes and also in deeper brain structures during ethologically relevant behaviors. Such studies will benefit immensely from the use of wearable endoscopes in combination with red shifted GECIs to permit imaging deeper into tissue [98]. Calcium integrators such as CaMPARI are also likely to be valuable [99].

Astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and neurodegenerative disease

It has been proposed that glia contribute to brain disease [100], and more specifically that astrocyte Ca2+ signals may participate in neurological and psychiatric disorders [101]. We emphasize recent evaluations in mouse models of two distinct neurodegenerative diseases in which astrocyte Ca2+ signaling was altered in separable ways.

Pioneering studies using FLIM in a mouse model of familial Alzheimer's disease (AD) showed that astrocytes displayed higher basal astrocyte Ca2+ levels and increased transient Ca2+ signals, which may represent a heightened Ca2+ signaling phenotype [81]. However, although it has been proposed that astrocyte Ca2+ signals can be triggered by action potential firing in some brain areas [5], within the cortex in vivo neither normal nor heightened Ca2+ signaling in AD model mice was the result of action potential firing in neurons [102]. The best available data show that heightened Ca2+ signaling arose because reactive astrocytes were located near β-amyloid plaques and because they displayed enhanced extracellular ATP-dependent P2Y1-receptor mediated Ca2+ signaling [102]. In support, heightened Ca2+ signaling could be blocked by pharmacological interventions that blocked ATP release from connexin hemi channels and by P2Y1 receptors antagonists [102]. Taken together, these data indicate that heightened astrocyte Ca2+ signals that accompany pathology in mouse models of AD may be caused by a combination of ATP release and/or increased P2Y1 receptor expression by a population of reactive astrocytes located near plaques. If so, P2Y1 receptors may represent a novel therapeutic target for AD. In addition, it is of great interest, and worthy of further evaluations in vivo, that direct application of low amounts of amyloid-β peptides to astrocytes can enhance astrocyte Ca2+ signals via a mechanism involving α7 nicotinic receptors [103, 104].

Several previous studies have implicated astrocytes in Huntington's disease (HD) [105-109]. Astrocyte Ca2+ signals have thus recently been explored in a mouse model of HD[110]. Notably, at the ages tested, HD model mice did not display astrogliosis [109] and thus the underlying changes that occur are separable from those observed in AD model mice, which are strongly associated with astrogliosis [102]. The experiments were conducted on striatal astrocytes in adult mice at early stages of symptom onset before overt tissue loss [110]. Wild type striatal astrocytes displayed extensive spontaneous Ca2+ signals, but did not respond reliably with Ca2+ elevations during synaptic glutamate release from cortical inputs [110]. In contrast, in HD model mice, spontaneous Ca2+ signals were significantly reduced in amplitude, frequency and duration, but astrocytes responded robustly to cortical stimulation with evoked action potential dependent Ca2+ signals [110]. The available data suggest that these evoked Ca2+ signals were accompanied by prolonged extracellular glutamate levels that activated mGluR2/3 receptors on astrocytes to cause Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. In this view, astrocyte engagement was tightly gated by Glt1 glutamate transporters, which presumably normally function to clear extracellular glutamate before it can reach astrocyte mGluR2/3 receptors. Interestingly, Ca2+ and glutamate signaling in astrocytes from HD model mice was rescued by astrocyte specific restoration of Kir4.1, which past studies show was reduced in HD and contributed to disease phenotypes [109]. These data imply that astrocyte contributions to HD model mice involve intimate functional interactions between two homeostatic pathways: K+ buffering and glutamate clearance. The reduction of these in HD results in dramatically altered Ca2+ signaling, but it remains to be determined if altered astrocyte Ca2+ signaling directly contributes to neuronal deficits in HD or if these are mainly modulated by altered K+ and glutamate levels. Nonetheless, early astrocyte dysfunctions that precede astrogliosis may represent novel therapeutic targets in HD. More broadly, it is of interest mechanistically that two neurodegenerative diseases are accompanied by distinctly altered astrocyte Ca2+ signaling [81, 102, 110]. This raises the possibility that astrocyte Ca2+ signaling contributes in very specific ways to specific brain disorders.

Concluding remarks

An important goal of modern neuroscience is to understand how neurons and neural circuits give rise to complex behaviors. This is one of the oldest questions in neurobiology, but the tools of modern biology now make it experimentally tractable. It is tempting to also ask how astrocytes contribute to neural circuits that underlie behavior. Such experiments are certainly needed and are underway [17, 111], but one ought to also consider the possibility that astrocytes may largely provide an appropriate substrate and milieu for neurons to perform their multifarious operations. Such astrocyte functions could be indispensable [100], but perhaps not directly related to the computations neurons perform to give rise to behavior per se. If this proves to be the case, and experiments are needed to prove or refute this idea, it may instead be productive to ask how astrocyte dysfunction drives neural circuit malfunction and how this contributes to phenotypic manifestations of disease. In other words, perhaps astrocyte dysfunctions drive disease mechanisms, but in otherwise healthy tissue astrocytes normally provide sustenance and a fabric on which neural circuits form and work. In these settings, astrocytes may be amenable to selective pharmacological, genetic and remote manipulation, or even replacement [112], with the goal of producing desirable effects within neural circuits to modify disease symptoms and outcomes. Early examples of such strategies are emerging and could be explored in other disorders [102, 109, 110, 112]. We believe this is a useful and new conceptual framework within which to consider astrocyte Ca2+ signals, however, it should also be considered that astrocytes regulate synaptic function as well as participate in and contribute to global brain states. Both of these existing ideas have been extensively reviewed already [17, 113]. Future research will be immeasurably advanced with the detailed understanding of astrocyte molecular mechanisms and the availability of methods with which to study additional aspects of astrocyte signaling. Many important questions remain unanswered in this field (see Outstanding Questions).

The last few years have witnessed vigorous debate on the physiological role(s) of astrocyte Ca2+ signals and if, how, why and when they contribute to neural circuit function. A summary of the relevant issues is provided by Bazargani and Attwell [2]. Recent advances with monitoring Ca2+ signals selectively within physiologically relevant astrocyte compartments in brain slices and in vivo for adult mice have now provided a more nuanced view of astrocyte Ca2+ signals and their relations to synaptic and neural circuit function. Many of these insights derive from the use of much improved methods. Taken together, these technique driven insights are fueling a new wave of astrocyte research [2] and stimulating new ideas. We are reminded of Sydney Brenner's insightful adage: “Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order”.

Highlights.

Astrocytes display intracellular Ca2+ signals

Improved methods have unearthed new types of astrocyte Ca2+ signals

Astrocyte basal Ca2+ levels are variable

In vivo studies suggest astrocytes display behaviorally relevant Ca2+ signaling

Astrocyte Ca2+ signaling is altered in neurodegenerative diseases

Outstanding Questions.

Molecular/Cellular

What are the molecular pathways that mediate various Ca2+ signals in astrocytes?

What are the role(s) of organelles, other than ER, for astrocyte Ca2+ signals?

What is the full set of molecular and physiological processes within astrocytes that Ca2+ controls?

Can new genetic methods be developed to broadly suppress astrocyte Ca2+ signals in defined brain areas?

Circuits

Are the functions of basal Ca2+ levels separable from those of Ca2+ elevations?

What are the correlative relations between astrocyte Ca2+ signals and neural circuit function and mouse behavior?

What are the causative functions of astrocyte Ca2+ signals for circuits and behavior?

Do astrocyte Ca2+ signals serve distinct functions in distinct circuits?

Disease

Can astrocyte biology be exploited to produce desirable effects in neural circuits associated with specific brain disorders?

Do altered astrocyte Ca2+ signals contribute to specific neurodegenerative diseases?

Acknowledgments

Work in the Khakh lab is supported by the CHDI Foundation and by NIH grants NS060677, MH099559 and MH104069. Eiji Shigetomi is supported by JSPS KAKENHI 25710005 and Takeda Science Foundation. Work in the Patel lab is supported by the BBSRC and Parkinson's UK. Thanks to Dmitri Rusakov (UCL) for permission to use Figure 4, the Janelia GENIE Project for help to make Figure 1 and David Attwell (UCL) for sharing unpublished work. The authors regret that many papers could not be cited (especially early pioneering studies), because of space limits and the editorial requirement to focus on studies from the last five years.

Footnotes

Author contributions: BSK, SP and ES worked on subsections separately. BSK drafted the final version and all authors commented and agreed on it.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Khakh BS, Sofroniew MV. Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:942–952. doi: 10.1038/nn.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazargani N, Attwell D. Astrocyte calcium signalling: the third wave. Nat Neurosci. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nn.4201. accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung WS, Allen NJ, Eroglu C. Astrocytes Control Synapse Formation, Function, and Elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015 Feb 6;7(9) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020370. pii: a020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haydon PG, Nedergaard M. How do astrocytes participate in neural plasticity? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014 Dec 11;7(3):a020438. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khakh BS, McCarthy KD. Astrocyte calcium signaling: from observations to functions and the challenges therein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015 Jan 20;7(4):a020404. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen ML, Khakh BS, Skatchkov SN, Zhou M, Lee CJ, Rouach N. New Insights on Astrocyte Ion Channels: Critical for Homeostasis and Neuron-Glia Signaling. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13827–13835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2603-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SJ. Do astrocytes process neural information? Prog Brain Res. 1992;94:119–136. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith S. Neural signalling. Neuromodulatory astrocytes. Curr Biol. 1994;4:807–810. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusakov DA. Disentangling calcium-driven astrocyte physiology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:226–233. doi: 10.1038/nrn3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volterra A, Liaudet N, Savtchouk I. Astrocyte Ca(2)(+) signalling: an unexpected complexity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:327–335. doi: 10.1038/nrn3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosche J, Matyash V, Möller T, Verkhratsky A, Reichenbach A, Kettenmann H. Microdomains for neuron-glia interaction: parallel fiber signaling to Bergmann glial cells. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2 doi: 10.1038/5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Castro MA, Chuquet J, Liaudet N, Bhaukaurally K, Santello M, Bouvier D, Tiret P, Volterra A. Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panatier A, Vallée J, Haber M, Murai KK, Lacaille JC, Robitaille R. Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell. 2011;146:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dani JW, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ. Neuronal activity triggers calcium waves in hippocampal astrocyte networks. Neuron. 1992;8:429–440. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90271-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: long-range glial signaling. Science. 1990;247:470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1967852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles AC, Merrill JE, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular signaling in glial cells: calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron. 1991;6:983–992. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90238-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG, Oliet SH, Robitaille R, Volterra A. Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron. 2014;81:728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirase H, Qian L, Bartho P, Buzsaki G. Calcium dynamics of cortical astrocytic networks in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong X, Shigetomi E, Looger LL, Khakh BS. Genetically encoded calcium indicators and astrocyte calcium microdomains. Neuroscientist. 2013;19:274–291. doi: 10.1177/1073858412468794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broussard GJ, Liang R, Tian L. Monitoring activity in neural circuits with genetically encoded indicators. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014 Dec 5;7:97. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00097. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell JT. Imaging calcium signals in vivo: a powerful tool in physiology and pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1605–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hires SA, Tian L, Looger LL. Reporting neural activity with genetically encoded calcium indicators. Brain Cell Biol. 2008;36:69–86. doi: 10.1007/s11068-008-9029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Looger LL. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akerboom J, Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Tian L, Marvin JS, Mutlu S, Calderon NC, Eposti F, Borghius BG, Sun XR, Gordus A, Orger MB, Portugues R, Engert F, Macklin JJ, Filosa A, Aggarwal A, Kerr R, Takagi R, Kracun S, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS, Baier H, Lagnado L, Wang SSH, Bargmann CI, Kimmel BE, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Kim DS, S ER, Looger LL. Optimisation of a GCaMP Calcium Indicator for Neural Activity Imaging. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13819–13840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohkura M, Sasaki T, Sadakari J, Gengyo-Ando K, Kagawa-Nagamura Y, Kobayashi C, Ikegaya Y, Nakai J. Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051286. Epub 2012 Dec 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shigetomi E, Bushong EA, Haustein MD, Tong X, Jackson-Weaver O, Kracun S, Xu J, Sofroniew MV, Ellisman MH, Khakh BS. Imaging calcium microdomains within entire astrocyte territories and endfeet with GCaMPs expressed using adeno-associated viruses. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:633–647. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shigetomi E, Kracun S, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS. A genetically targeted optical sensor to monitor calcium signals in astrocyte processes. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:759–766. doi: 10.1038/nn.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shigetomi E, Tong X, Kwan KY, Corey DP, Khakh BS. TRPA1 channels regulate astrocyte resting calcium and inhibitory synapse efficacy through GAT-3. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:70–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gee JM, Gibbons MB, Taheri M, Palumbos S, Morris SC, Smeal RM, Flynn KF, Economo MN, Cizek CG, Capecchi MR, Tvrdik P, Wilcox KS, White JA. Imaging activity in astrocytes and neurons with genetically encoded calcium indicators following in utero electroporation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015 Apr 15;8:10. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00010. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Wang X, Zhang N, Gottipati MK, Parpura V, Ding S. Imaging of mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics in astrocytes using cell-specific mitochondria-targeted GCaMP5G/6s: mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and cytosolic Ca2+ availability via the endoplasmic reticulum store. Cell Calcium. 2014;56:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki J, Kanemaru K, Ishii K, Ohkuram M, Okubom Y, Iino M. Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat Commun. 2014 Jun 13;5:4153. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca²+ indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson MJ, Baldwin HA, Werley CA, Boccardo S, Whitaker LR, Yan X, Holt GT, Schreiter ER, Looger LL, Cohen AE, Kim DS, Harvey BK. A Low Affinity GCaMP3 Variant (GCaMPer) for Imaging the Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Store. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 9;10(10):e0139273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139273. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horikawa K, Yamada Y, Matsuda T, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto M, Matsu-ura T, Miyawaki A, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, Nagai T. Spontaneous network activity visualized by ultrasensitive Ca(2+) indicators, yellow Cameleon-Nano. Nat Methods. 2010;7:729–732. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paukert M, Agarwal A, Cha J, Doze VA, Kang JU, Bergles DE. Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron. 2014;82:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srinivasan R, Huang BS, Venugopal S, Johnston AD, Chai H, Zeng H, Golshani P, Khakh BS. Ca(2+) signaling in astrocytes from Ip3r2(-/-) mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:708–717. doi: 10.1038/nn.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun XR, Badura A, Pacheco DA, Lynch LA, Schneider ER, Taylor MP, Hogue IB, Enquist LW, Murthy M, Wang SS. Fast GCaMPs for improved tracking of neuronal activity. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2170. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortinski PI, Dong J, Mungenast A, Yue C, Takano H, Watson DJ, Haydon PG, Coulter DA. Selective induction of astrocytic gliosis generates deficits in neuronal inhibition. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:584–591. doi: 10.1038/nn.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zariwala HA, Borghuis BG, Hoogland TM, Madisen L, Tian L, De Zeeuw CI, Zeng H, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Chen TW. A Cre-dependent GCaMP3 reporter mouse for neuronal imaging in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3131–3141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4469-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang R, Haustein MD, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS. Imaging intracellular Ca²+ signals in striatal astrocytes from adult mice using genetically-encoded calcium indicators. J Vis Exp. 2014 Nov 19;(93):e51972. doi: 10.3791/51972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haustein MD, Kracun S, Lu XH, Shih T, Jackson-Weaver O, Tong X, Xu J, Yang XW, O'Dell TJ, Marvin JS, Ellisman MH, Bushong EA, Looger LL, Khakh BS. Conditions and constraints for astrocyte calcium signaling in the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway, Neuron. 2014;82:413–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonder DE, McCarthy KD. Astrocytic Gq-GPCR-linked IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signaling does not mediate neurovascular coupling in mouse visual cortex in vivo. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13139–13150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2591-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sofroniew MV. Transgenic techniques for cell ablation or molecular deletion to investigate functions of astrocytes and other GFAP-expressing cell types. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;814:531–544. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia AD, Doan NB, Imura T, Bush TG, Sofroniew MV. GFAP-expressing progenitors are the principal source of constitutive neurogenesis in adult mouse forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1233–1241. doi: 10.1038/nn1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shigetomi E, Jackson-Weaver O, Huckstepp RT, O'Dell TJ, Khakh BS. TRPA1 channels are regulators of astrocyte basal calcium levels and long-term potentiation via constitutive D-serine release. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10143–10153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5779-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanemaru K, Sekiya H, Xu M, Satoh K, Kitajima N, Yoshida K, Okubo Y, Sasaki T, Moritoh S, Hasuwa H, Mimura M, Horikawa K, Matsui K, Nagai T, Iino M, Tanaka KF. In vivo visualization of subtle, transient, and local activity of astrocytes using an ultrasensitive Ca(2+) indicator. Cell Rep. 2014;8:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atkin SD, Patel S, Kocharyan A, Holtzclaw LA, Weerth SH, Schram V, Pickel J, Russell JT. Transgenic mice expressing a cameleon fluorescent Ca2+ indicator in astrocytes and Schwann cells allow study of glial cell Ca2+ signals in situ and in vivo. J Neursci Methods. 2009;181:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang W, Szokol K, Jensen V, Enger R, Trivedi CA, Hvalby Ø, Helm PJ, Looger LL, Sprengel R, Nagelhus EA. Stimulation-evoked Ca2+ signals in astrocytic processes at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses of adult mice are modulated by glutamate and ATP. J Neurosci. 2015;35:3016–3021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Enger R, Tang W, Vindedal GF, Jensen V, Johannes Helm P, Sprengel R, Looger LL, Nagelhus EA. Dynamics of Ionic Shifts in Cortical Spreading Depression. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:4469–4476. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szokol K, Heuser K, Tang W, Jensen V, Enger R, Bedner P, Steinhäuser C, Taubøll E, Ottersen OP, Nagelhus EA. Augmentation of Ca(2+) signaling in astrocytic endfeet in the latent phase of temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015 Feb 25;9:49. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00049. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gee JM, Smith NA, Fernandez FR, Economo MN, Brunert D, Rothermel M, Morris SC, Talbot A, Palumbos S, Ichida JM, Shepherd JD, West PJ, Wachowiak M, Capecchi MR, Wilcox KS, White JA, Tvrdik P. Imaging activity in neurons and glia with a Polr2a-based and cre-dependent GCaMP5G-IRES-tdTomato reporter mouse. Neuron. 2014;83:1058–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akerboom J, Carreras Calderon N, Tian L, Wabnig S, Prigge M, Tolo J, Gordus A, Orger MB, Severi KE, Macklin JJ, Patel R, Pulver SR, Wardill TJ, Fischer E, Schuler C, Chen TW, Sarkisyan KS, Marvin JS, Bargmann CI, Kim DS, Kugler S, Lagnado L, Hegemann P, Gottschalk A, Schreiter ER, Looger LL. Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multi-color neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics. Front Mol Neurosci. 2013;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shigetomi E, Kracun S, Khakh BS. Monitoring astrocyte calcium microdomains with improved membrane targeted GCaMP reporters. Neuron Glia Biol. 2010;6:183–191. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X10000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madisen L, Garner AR, Shimaoka D, Chuong AS, Klapoetke NC, Li L, van der Bourg A, Niino Y, Egolf L, Monetti C, Gu H, Mills M, Cheng A, Tasic B, Nguyen TN, Sunkin SM, Benucci A, Nagy A, Miyawaki A, Helmchen F, Empson RM, Knöpfel T, Boyden ES, Reid RC, Carandini M, Zeng H. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron. 2015;85:942–958. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel S, Docampo R. Acidic calcium stores open for business: expanding the potential for intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery JM, Adams JA, Ikura M, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill JM, De Stefani D, Jones AW, Ruiz A, Rizzuto R, Szabadkai G. Measuring baseline Ca(2+) levels in subcellular compartments using genetically engineered fluorescent indicators. Methods Enzymol. 2014;543:47–72. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801329-8.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oberheim NA, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Heterogeneity of astrocytic form and function. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;814:23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Y, Barres BA. Astrocyte heterogeneity: an underappreciated topic in neurobiology. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma K, Schmitt S, Bergner CG, Tyanova S, Kannaiyan N, Manrique-Hoyos N, Kongi K, Cantuti L, Hanisch UK, Philips MA, Rossner MJ, Mann M, Simons M. Cell type- and brain region-resolved mouse brain proteome. Nat Neurosci. 2015 Nov 2; doi: 10.1038/nn.4160. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reeves AM, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS. Bulk loading of calcium indicator dyes to study astrocyte physiology: key limitations and improvements using morphological maps. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9353–9358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0127-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, McCarthy KD. Sorting out astrocyte physiology from pharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:151–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Porter JT, McCarthy KD. Astrocytic neurotransmitter receptors in situ and in vivo. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;51:439–455. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petravicz J, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Loss of IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ increases in hippocampal astrocytes does not affect baseline CA1 pyramidal neuron synaptic activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4967–4973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Science. 2010;327:1250–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.1184821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petravicz J, Boyt KM, McCarthy KD. Astrocyte IP3R2-dependent Ca(2+) signaling is not a major modulator of neuronal pathways governing behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014 Nov 12;8:384. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00384. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takano T, He W, Han X, Wang F, Xu Q, Wang X, Oberheim Bush NA, Cruz N, Dienel GA, Nedergaard M. Rapid manifestation of reactive astrogliosis in acute hippocampal brain slices. Glia. 2014;62:78–95. doi: 10.1002/glia.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Otsu Y, Couchman K, Lyons DG, Collot M, Agarwal A, Mallet JM, Pfrieger FW, Bergles DE, Charpak S. Calcium dynamics in astrocyte processes during neurovascular coupling. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:210–218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherwood MW, Arizono M, Hisatsune C, Bannai H, Ebisui E, Sherwood JL, Panatier A, Oliet SH, Mikoshiba K. Dissecting the role of IP3-Receptor subtypes in hippocampal LTP. Society for Neuroscience Abstract 297.04/B89. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ventura R, Harris KM. Three-dimensional relationships between hippocampal synapses and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6897–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J Neurosci. 2002;22:183–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hama K, Arii T, Katayama E, Marton M, Ellisman MH. Tri-dimensional morphometric analysis of astrocytic processes with high voltage electron microscopy of thick Golgi preparations. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:277–285. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044189.08240.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Benediktsson AM, Schachtele SJ, Green SH, Dailey ME. Ballistic labeling and dynamic imaging of astrocytes in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;141:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ho KW, Lambert WS, Calkins DJ. Activation of the TRPV1 cation channel contributes to stress-induced astrocyte migration. Glia. 2014;62:1435–1451. doi: 10.1002/glia.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Di Castro MA, Chuquet J, Liaudet N, Bhaukaurally K, Santello M, Bouvier D, Tiret P, Volterra A. Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat Neurosci. 2011;10:1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 3rd. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kuchibhotla KV, Lattarulo CR, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science. 2009;323:1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1169096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zheng K, Bard L, Reynolds JP, King C, Jensen TP, Gourine AV, Rusakov DA. Time-Resolved Imaging Reveals Heterogeneous Landscapes of Nanomolar Ca(2+) in Neurons and Astroglia. Neuron. 2015;88:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilms CD, Schmidt H, Eilers J. Quantitative two-photon Ca2+ imaging via fluorescence lifetime analysis. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wilms CD, Eilers J. Photo-physical properties of Ca2+-indicator dyes suitable for two-photon fluorescence-lifetime recordings. J Microsc. 2007;225:209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun W, McConnell E, Pare JF, Xu Q, Chen M, Peng W, Lovatt D, Han X, Smith Y, Nedergaard M. Glutamate-dependent neuroglial calcium signaling differs between young and adult brain. Science. 2013;339:197–200. doi: 10.1126/science.1226740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenegger DG, Tran CH, W C JI, Gordon GR. Tonic Local Brain Blood Flow Control by Astrocytes Independent of Phasic Neurovascular Coupling. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13463–13474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1780-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thrane AS, Rangroo Thrane V, Zeppenfeld D, Lou N, Xu Q, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M. General anesthesia selectively disrupts astrocyte calcium signaling in the awake mouse cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18974–18979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nimmerjahn A, Mukamel EA, Schnitzer MJ. Motor behavior activates Bergmann glial networks. Neuron. 2009;62:400–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schummers J, Yu H, Sur M. Tuned responses of astrocytes and their influence on hemodynamic signals in the visual cortex. Science. 2008;320:1638–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1156120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ding F, O'Donnell J, Thrane AS, Zeppenfeld D, Kang H, Xie L, Wang F, Nedergaard M. alpha1-Adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice. Cell Calcium. 2013;54:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bekar LK, He W, Nedergaard M. Locus coeruleus alpha-adrenergic-mediated activation of cortical astrocytes in vivo. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2789–2795. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hertz L, Lovatt D, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Adrenoceptors in brain: cellular gene expression and effects on astrocytic metabolism and [Ca(2+)]i. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gordon GR, Baimoukhametova DV, Hewitt SA, Rajapaksha WR, Fisher TE, Bains JS. Norepinephrine triggers release of glial ATP to increase postsynaptic efficacy. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1078–1086. doi: 10.1038/nn1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takata N, Mishima T, Hisatsune C, Nagai T, Ebisui E, Mikoshiba K, Hirase H. Astrocyte calcium signaling transforms cholinergic modulation to cortical plasticity in vivo. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18155–18165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen N, Sugihara H, Sharma J, Perea G, Petravicz J, Le C, Sur M. Nucleus basalis-enabled stimulus-specific plasticity in the visual cortex is mediated by astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;109:E2832–2841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206557109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Niell CM, Stryker MP. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;65:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keller GB, Bonhoeffer T, Hübener M. Sensorimotor mismatch signals in primary visual cortex of the behaving mouse. Neuron. 2012;74:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hamel EJ, Grewe BF, Parker JG, Schnitzer MJ. Cellular level brain imaging in behaving mammals: an engineering approach. Neuron. 2015;86:140–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fosque BF, Sun Y, Dana H, Yang CT, Ohyama T, Tadross MR, Patel R, Zlatic M, Kim DS, Ahrens MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Schreiter ER. Neural circuits. Labeling of active neural circuits in vivo with designed calcium integrators. Science. 2015;347:755–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1260922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chung WS, Welsh CA, Barres BA, Stevens B. Do glia drive synaptic and cognitive impairment in disease? Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1539–1545. doi: 10.1038/nn.4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nedergaard M, Rodríguez JJ, Verkhratsky A. Glial calcium and diseases of the nervous system. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Delekate A, Füchtemeier M, Schumacher T, Ulbrich C, Foddis M, Petzold GC. Metabotropic P2Y1 receptor signalling mediates astrocytic hyperactivity in vivo in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5422. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee L, Kosuri P, Arancio O. Picomolar amyloid-β peptides enhance spontaneous astrocyte calcium transients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:49–62. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pirttimaki TM, Codadu NK, Awni A, Pratik P, Nagel DA, Hill EJ, Dineley KT, Parri HR. α7 Nicotinic receptor-mediated astrocytic gliotransmitter release: Aβ effects in a preclinical Alzheimer's mouse model. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081828. eCollection 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shin JY, Fang ZH, Yu ZX, Wang CE, Li SH, Li XJ. Expression of mutant huntingtin in glial cells contributes to neuronal excitotoxicity. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:1001–1012. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Faideau M, Kim J, Cormier K, Gilmore R, Welch M, Auregan G, Dufour N, Guillermier M, Brouillet E, Hantraye P, Déglon N, Ferrante RJ, Bonvento G. In vivo expression of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin by mouse striatal astrocytes impairs glutamate transport: a correlation with Huntington's disease subjects. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3053–3067. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bradford J, Shin JY, Roberts M, Wang CE, Li XJ, Li S. Expression of mutant huntingtin in mouse brain astrocytes causes age-dependent neurological symptoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22480–22485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911503106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bradford J, Shin JY, Roberts M, Wang CE, Sheng G, Li S, Li XJ. Mutant huntingtin in glial cells exacerbates neurological symptoms of Huntington disease mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10653–10661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tong X, Ao Y, Faas GC, Nwaobi SE, Xu J, Haustein MD, Anderson MA, Mody I, Olsen ML, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS. Astrocyte Kir4.1 ion channel deficits contribute to neuronal dysfunction in Huntington's disease model mice. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:694–703. doi: 10.1038/nn.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jiang R, Diaz-Castro B, Looger LL, Khakh BS. Dysfunctional calcium and glutamate signaling in striatal astrocytes from Huntington's disease model mice. J Neurosci. 2016 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3693-15.2016. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Halassa MM, Haydon PG. Integrated brain circuits: astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:335–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Han X, Chen M, Wang F, Windrem M, Wang S, Shanz S, Xu Q, Oberheim NA, Bekar L, Betstadt S, Silva AJ, Takano T, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Forebrain engraftment by human glial progenitor cells enhances synaptic plasticity and learning in adult mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nimmerjahn A, Bergles DE. Large-scale recording of astrocyte activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;32:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]